There was another rush of small bumps and a short straight drop. They fell into another night. There was land below – a dark country at the edge of a black sea. But there were lights too – the soft glow and then clear lines of street lamps, a grid of them, then light spilling from buildings.

They landed in thick warm coats at the edge of a street. Al’s was black, Lexi’s was light brown with ivory buttons. When she moved, she felt the new leather of her boots creak. There was a mist in the air and it glowed around the lamps.

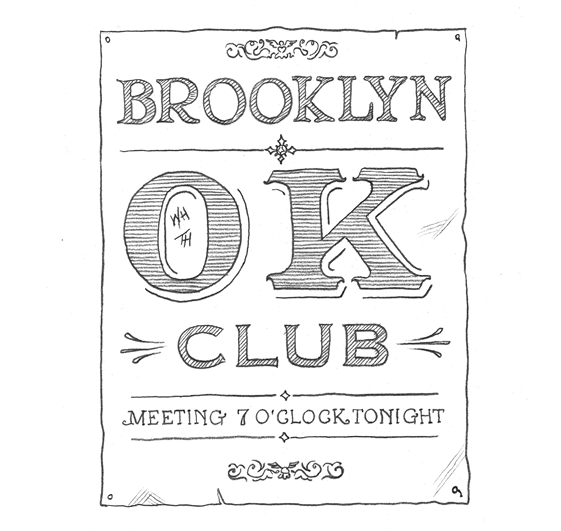

‘I don’t think we have to look too far this time.’ She pointed to a sign that read ‘Brooklyn OK Club, meeting

7 o’clock tonight’. Her hands were in some kind of fur tube and she pulled them out in a panic to check the portal. ‘No soap.’ She laughed. ‘I’m glad that’s over.’

A carriage stopped and four people climbed down, then walked up the steps into the building. The men were wearing top hats and the women had furs around their shoulders.

‘That looks like what we’re dressed for. Let’s see when this is.’ Al reached for the single silver buckle on his black satchel. When he opened it the leather smelt new. Then Doug burped and it smelt like 14 kinds of cheese. ‘The time’s good. Really good.’ He showed the peg to Lexi.

‘This is it, then.’ She folded the fur hand warmer and pushed it into her pocket. ‘I guess it’ll be in there. Or at least that’s where we have to start.’

‘If we’d stayed longer at City Hall last time, do you think we’d have missed it completely?’ It had been bothering Al. ‘Does it come up once and, if you’re not in the right spot, is that it? Or would there have been another chance when the ads got published? Maybe that was the real chance.’

‘I think you might be mistaking me for Caractacus. Put it on the list, if you want.’ She didn’t want to think about it, or to think that one wrong move could see them stuck. ‘Maybe us being there triggers it. But let’s go get this one. And let’s hope it’ll fit in your bag.’

As they crossed the road, she took a closer look at the sign about the meeting. There in the middle of the ‘O’ of ‘OK’ she could make out the initials ‘WH’ and ‘TH’. They were on track. There was still no sign of Grandad Al, though. If he hadn’t done ‘okay’, he wouldn’t know to head to Brooklyn on this particular night five years after Nantucket. It was too much to hope that he’d be in the crowd. But they were closer at least.

‘You’re here for OK?’ the man on the door said when they reached the top of the steps.

Lexi couldn’t believe it was so easy. ‘We’re definitely here for OK.’

She and Al took a step inside the meeting room and checked for a portal, but nothing showed itself. ‘OK’ was everywhere, though. A woman passed them each an ‘OK’ ribbon from a box and there were banners on the walls reading ‘Vote for OK’. There were wooden chairs set out in rows, most of them with people on them already.

‘I’m assuming this isn’t all about soap,’ Al said.

‘Have you noticed how this one keeps being “okay”, however you spell it? It’s not like “harrow, halloo, hello”. I thought it’d change more.’ Lexi was starting to wish the rules were the same each time. Or, if they weren’t the same, she wished she understood them better. ‘I wonder why we had to meet Mr Pyle and find out about his soap?’

‘Oh, wonderful,’ a man said, looking right at her. He had a medal on the breast of his black coat. ‘You are the twins, aren’t you? The ribbons go here.’ He indicated his ribbon, which was on his lapel. ‘Do you need to wear those keys? Could the ribbons go over them, perhaps – just for now?’ he kept smiling. He didn’t seem to need answers. ‘I’m Talbot. You’ll have been told to look out for Talbot, I assume? Mr Talbot? Follow me.’

It felt as if they had no choice. Al checked the room as they went and he could see Lexi doing the same. It might not be the crazy ancient past, but things had gone wrong before when they’d least expected it.

Mr Talbot took them to the right and along the side of the audience, to steps leading to a door beside the stage. He knocked on it and it opened.

‘Oh, the children,’ another man’s voice said from inside. ‘The twins. Thank you, Mr Talbot.’

The door opened fully and Mr Talbot ushered them in. Al could feel himself tensing up. But it was 1840, a meeting house. No one would be here shooting kings or invading or robbing.

‘Right,’ the new man said, even before the door had closed behind them. ‘We’re planning to keep the introductions brief – brief, but rousing. We need them in the right frame of mind when the president comes on.’ He had a dark moustache, a satchel quite like Al’s and a small bunch of flowers in one hand. ‘You’ll go out as soon as the president has finished speaking.’ He passed the flowers to Lexi. ‘You’ll give him this.’ He was staring at the flowers as if they needed to be checked again. ‘They’re mostly things you could find in your garden. Nice and simple. We think that’s the right message.’

He opened his satchel and took out several copies of a document.

‘Are they for me?’ Al said. He wondered what he might have to do with them.

The man checked the documents and didn’t look up. ‘Only if you want to be ready for any last-minute questions OK might have about Texas.’ He ran his finger further down the page. ‘We’ve reached a settlement with Mexico to deny Texas’s request to become part of the United States.’

Lexi and Al glanced around the room, but still nothing was glowing. It was dark backstage and a portal wouldn’t have been hard to see. How much ‘okay’ would there be in 1840 before the portal appeared?

‘Andrew Morrell.’ The man finally looked up. ‘Aide to the president. I’m the one who exchanged letters with your parents. I thought you’d look more alike, but no matter. They might have dressed you more alike. You’ll have to take the coats off.’

‘Questions OK might have?’ Al wanted to get back to that, and away from Andrew Morrell’s focus on details that didn’t make a lot of sense.

‘Yes, OK – the president, Mr Van Buren, Old Kinderhook.’ He looked at them both to make sure his point had got through. ‘Did your parents tell you nothing? OK. From Kinderhook, New York, where he was born. OK’s what we’re going with now. OK clubs, OK ribbons. It sounds—’ He paused, to find the right word. ‘Affectionate, like the right kind of name for a man of the people. We need to undo all the talk going around about him hosting huge banquets for European ministers when money was tight in ’37. They’re wrong about him, you know. He wears the finest suits to be found in Manhattan, but they’re all bought from his own pocket.’

It was politics, Lexi realised. As their parents often said in the 21st century, politics should have been about big things, but too often it was about how wrong your dress was or how your hair was cut.

‘Is that how OK started?’ Al asked him. It felt unusual to say something so direct, but he couldn’t see why he shouldn’t. ‘You came up with it for this campaign?’

‘I think it is. I think we started it. Or one of the others saw it in a newspaper.’ He looked around, as if whoever saw it might be nearby. ‘Yes, that was it. It was the Boston Morning Post, sometime last year. It was that game they were playing, printing expressions with the wrong initials and spelling, as if they’d been written by people who didn’t know better. It’s ours now, though. Whenever people think OK, it’s the president they’ll be thinking of.’ Suddenly he stopped and ignored them completely. ‘Mr President—’

‘Andrew.’ An older man stepped forward and stood beside Al, though he didn’t seem to notice him. The top of his head was a bald dome, with grey woolly hair sprouting from the sides, and mutton-chop whiskers. He had a top hat in one hand and an elegant cane in the other. ‘You have that bill ready for me?’