CHAPTER 1

Republic in Peril

No, you dare not make war on cotton.

No power on earth dares make war upon it. Cotton is King!

—SENATOR JAMES H. HAMMOND of South Carolina, March 4, 1858

The firm and universal conviction here is, that Great Britain,

France, and Russia will acknowledge us at once in the family of nations.

—SENATOR THOMAS R. R. COBB of Georgia, February 21, 1861

What possible chance can the South have?

—CALEB CUSHING of New York, late April 1861

Supporters of the Confederate States of America regarded themselves as the true progenitors of the republic and their secession from the Union as a return to the world of limited national government envisioned by the Founding Fathers. In his Inaugural Address of February 1861 delivered in Montgomery, Alabama, President Jefferson Davis declared: “We have assembled to usher into existence the Permanent Government of the Confederate States. Through this instrumentality, under the favor of Divine Providence, we hope to perpetuate the principles of our revolutionary fathers…. Therefore we are in arms to renew such sacrifices as our fathers made to the holy cause of constitutional liberty.” Thus from the southern perspective, the Union was in peril, but not from the secessionists; rather, the danger came from a big government in Washington that had subverted the original Union's emphasis on states' rights into a northern tyranny. Southerners sought to unseat the northern power brokers who had devised an oppressive central government that had for too long trampled on the minority South by violating its right to manage its own affairs, whether tariffs, internal improvements, or slavery. The Union, as southerners saw it, had become an overly centralized governing mechanism run by a repressive northern majority. The agreement underlying the Philadelphia compact of 1787 had been broken; secession was the only remedy.1

Shortly after the Civil War erupted in April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln asserted that his central objective was to preserve the Union based on a strong federal government created by the Founding Fathers. Secession therefore posed its most severe challenge because the South's attempt to stand on its own would destroy that Union. “The right of revolution,” he wrote, “is never a legal right. The very term implies the breaking, and not the abiding by, organic law. At most, it is a moral right, when exercised for a morally justifiable cause.” Otherwise, revolution is “simply a wicked exercise of physical power.” In his Inaugural Address of March 1861, he declared: “I hold, that in contemplation of universal law, and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual.” No government ever included “a provision in its organic law for its own termination.” Secession was “the essence of anarchy.”2

On many levels Davis and Lincoln waged a war for the very survival of the republic as each president defined the vision of the Founding Fathers. Well known were Davis's advantages in military leadership from the beginning of the war; also well known was Lincoln's frustrating search for a general who could rally a massive yet ineptly led war machine to victory. Lesser known were the two presidents' struggles on an international level—Davis's efforts to win diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy and hence the right to negotiate military and commercial treaties, and Lincoln's attempts to ward off a foreign intervention in the war that could have led to southern alliances undermining the Union. Whereas Davis sought to maintain the status quo—a southern civilization built on slavery and dependent on the Constitution's guarantees of property—Lincoln soon tried to construct an improved America based on ending slavery and adhering to the natural rights doctrine that underlay the Declaration of Independence. Davis considered the war a struggle for liberty, which he defined as the absence of governmental interference in state, local, and personal affairs—including the right to own slaves. In contrast, Lincoln came to regard the war as the chief means for forming a more perfect Union emanating from a new birth of freedom that fellow white northerners interpreted as the political and economic freedoms enjoyed under the Constitution but that he expanded to include the death of slavery and the Old South. Davis had such a legalistic mind that he thought the European powers relied on international law only when it served their self-interest; Lincoln was highly pragmatic, knowing he had to convince the foreign governments that it was not in their best interest to intervene in America's affairs. Davis appealed to Europe to acknowledge southern independence as a righteous cause and welcome the Confederacy into the community of nations; Lincoln insisted that the conflict in America was a purely domestic concern and warned that any outside interference meant war with the Union.3

Both sets of arguments were morally and legally defensible and thereby right, making the two opposing leaders' positions irreconcilable and, combined with the vendettalike infighting that often comes in a familial contest, ensuring a massive bloodletting that would stop only when both sides were exhausted.

From the outbreak of the Civil War, the Confederacy's chief objective in foreign affairs was to secure diplomatic recognition from England first and then other European powers. Loans, a morale boost, military and economic assistance, perhaps even an alliance—everything was possible once the Confederacy won recognition as a nation. Shortly after the creation of its government in Montgomery in February 1861, the South sent three commissioners abroad, assigned to Great Britain, France, Russia, and Belgium, but always looking first to London. By no means did they expect British sympathy for their cause; not only were the British cold practitioners of a foreign policy grounded in self-interest, but also they opposed slavery, having outlawed it within their empire in 1833 and then hosting World Antislavery Conventions in London during the early 1840s. Furthermore, strong ties had developed between antislavery advocates in England and the United States. True, the British were not as staunchly antislavery as earlier, but they still supported abolition. Some of the more radical abolitionists, in fact, argued that southern independence would bring an end to slavery by making the region vulnerable to the influence of adjoining free territories. Southerners assumed that British sympathies would initially go to the Union and prepared to argue that the sectional struggle did not focus on slavery but on their drive for independence against an oppressive northern majority.4

Confederate leaders appealed to British self-interest by reminding their Atlantic cousins that mutual economic needs based on cotton tied them together. Thus “King Cotton Diplomacy” held the key to Confederate recognition and hence victory in the war. In 1858 Senator James H. Hammond of South Carolina insisted that if the South withheld cotton, “England would topple headlong and carry the whole civilized world with her, save the South. No, you dare not make war on cotton. No power on earth dares make war upon it. Cotton is King!” On December 12, 1860, just eight days before South Carolina announced secession, Senator Louis T. Wigfall of Texas confidently asserted in that august chamber: “I say that cotton is King, and that he waves his scepter not only over these thirty-three States, but over the island of Great Britain and over continental Europe.” A leading southerner assured a colleague that cotton was “the king who can shake the jewels in the crown of Queen Victoria.”5

The South appeared correct in assuming the overweening importance of cotton at home and abroad. The 1850s had been a time of great profit for cotton growers. The North, many southerners believed, needed the product so badly (about a fifth of the South's cotton went to markets above the Mason-Dixon Line by 1860) that it had no choice but to accept secession. As for the British, they consumed three times that amount and must extend recognition to the Confederacy in an effort to maintain the flow. If the North resisted secession, the British would act out of self-interest and intervene on behalf of the South. Up to 85 percent of the product they imported came from the South. A great portion of Britain's economic base—the textile industry and its five million workers—depended on southern cotton.6

The South's only concern, which it quickly dismissed, was that the British might seek other sources of cotton. Their Cotton Supply Association had already engaged in a search around the globe. But secession's supporters argued persuasively that the British had failed to increase their draw from India, which had offered the greatest potential alternative source. The South's cotton was king and hence its chief means for attaining recognition. The Richmond Whig boasted that the Confederacy had “its hand on the mane of the British lion, and that beast, so formidable to all the rest of the world, must crouch at her bidding.”7

By every economic measure, King Cotton Diplomacy should have won British recognition of southern independence. Cotton provided the breath of life for the Confederacy, and it surely was the lifeblood of the British textile industry. American cotton was purer and cheaper than that from India. In the two decades preceding the Civil War, British manufacturers turned to the South for most of their cotton supply. France and other nations in Europe were proportionately as reliant, although none of their production figures matched those in England. The British recognized the danger in becoming overly dependent on the South, but they also knew that Indian cotton lacked comparable quality. The latter, according to the Economist in April 1861, “yields more waste, that is, loses more in the process of spinning” because of the dirt and other particles gathered in the lint. “The Surat [Indian cotton] when cleaned, though of a richer color than the bulk of the American, is always much shorter in staple or fibre; the result of which is that in order to make it into equally strong yarn it requires to be harder twisted…. The consequence is that the same machinery will give out from 10 to 20% more American yarn than Surat yarn.” American cotton “spins better, does not break so easily and cause delay in work.” The cloth from Surat cotton “does not take the finish so well, and is apt, after washing, to look poor and thin…. In all respects (except color) the Indian cotton is an inferior article.”8

By 1860, more than four million people of about twenty-one million in the British Isles owed their livelihood to the cotton mills. The Times of London later warned that “so nearly are our interests intertwined with America that civil war in the States means destitution in Lancashire.” Soon afterward it proclaimed that “the destiny of the world hangs on a thread—never did so much depend on a mere flock of down!” A writer in De Bow's Review declared that a loss of southern cotton to England would lead to “the most disastrous political results—if not a revolution.” President Davis and his advisers were so confident in the leverage of cotton, according to his wife, that “foreign recognition was looked forward to as an assured fact.” They counted on “the stringency of the English cotton market, and the suspension of the manufactories, to send up a ground-swell from the English operatives, that would compel recognition.” The mere threat of a cotton cutoff, the South concluded, would force England to intervene in the war.9

The Confederacy, however, had overestimated the importance of cotton to diplomacy. The implicit though heavy-handed threat of extortion by slaveholders almost immediately alienated the British. In mid-January 1861 the Saturday Review in London warned that “it will be national suicide if we do not strain every nerve to emancipate ourselves from moral servitude to a community of slaveowners.” Later that month, the Economist likewise blasted King Cotton Diplomacy. How could southerners think that British merchants would want their government to “interfere in a struggle between the Federal Union and revolted states, and interfere on the side of those they deem willfully and fearfully in the wrong, simply for the sake of buying their cotton at a cheaper rate?” Furthermore, in a strange twist of fate, the region's economic successes hurt its drive for recognition. Southern farmers had produced bumper crops in the two seasons preceding secession winter, saddling both England and France with an enormous surplus of cotton. In early February 1861, the Economist issued a warning sign, denying the need for cotton and asserting that “the stock of cotton in our ports has never been so large as now.” But no Confederate official carefully examined the King Cotton premise. Moreover, southern strategists had overlooked the concurrent surge in British reliance on northern grains and foodstuffs during the 1850s, which had received impetus from their repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. Britain depended on wheat imports from the Union that would predictably increase because of lower costs than in Europe. The need for wheat joined with other concerns to severely weaken King Cotton Diplomacy.10

The Confederacy nonetheless counted on cotton to overcome all obstacles to recognition, including British antipathy toward slavery, and fell under the illusion that success would come as a matter of course. In reality, southerners had no other viable economic options than King Cotton Diplomacy. Their greatest assets lay in slaves and real estate, neither of which was easily convertible into money. Cotton as collateral for loans, of course, carried little weight in light of England and France's huge surplus that would probably last into the fall of 1862. In addition, the Confederacy never officially implemented a cotton embargo. Davis did not support such a measure, despite authorization by some states, and Confederate leaders put an export tax on cotton and tacitly approved holding back supplies. The Confederacy's almost total dependence on outside manufactures dictated a turn to Europe for war necessities and other goods—a need hampered by its small fleet of ten viable merchant vessels. It was no surprise that on numerous occasions southern spokesmen ignored these hard realities and referred to either justice or divine intervention in asserting the surety of diplomatic recognition. A young southern patriot proudly chided the Times's military correspondent in the United States, William H. Russell: “The Yankees ain't such cussed fools as to think they can come here and whip us, let alone the British.” “Why, what have the British got to do with it?” asked Russell. “They are bound to take our part,” came the reply without hesitation and perhaps with a smirk. “If they don't we'll just give them a hint about cotton, and that will set matters right.”11

To facilitate recognition, southerners tried to make slavery a nonissue. Louisiana secessionists told the British consul in New Orleans how much they wanted European support and, not by coincidence, took the occasion to offer assurances that their new government opposed reopening the African slave trade. Alabama and Georgia soon joined Louisiana in denouncing this “infamous traffic,” as did southern leaders then gathered in Montgomery to form their new government. Indeed, the Montgomery convention opening in early February 1861 required the Confederate Congress to outlaw the practice.12

British contemporaries remained skeptical about the South's efforts to diminish the importance of the peculiar institution. The great majority of workers hated slavery and favored the Union because of its emphasis on democracy and free labor. The Economist accused the South of lacking “scruples” and “morality” in supporting a system “strangely warped by slavery.” British Conservatives were torn by their opposition to the democracy associated with the Union and by their hesitation to support a southern struggle for nationalism that rested on a secession doctrine conducive to the same government disorder underlying the recent revolutions on the Continent. Despite the oft-argued claim that the so-called aristocratic South appealed to British Conservatives, they had found in their visits to the region that it was backward and based on slavery, whereas the North was industrialized, based on free labor, and more advanced. The highly heralded cities of Richmond and Charleston, in particular, were stricken by poverty and decay and greatly disappointed British travelers. Most of the British press considered slavery the root of America's troubles. Punch in London made its position clear when it sneered at the Confederacy as “Slaveownia.”13

The French likewise thought slavery lay at the heart of the sectional division in America. Numerous French journals joined Liberals and the public in considering Harriet Beecher Stowe's best-selling novel Uncle Tom's Cabin an accurate portrayal of slavery's inhumanity in the South and a sure stimulus to servile war. The Liberal opposition party perhaps seized on the slavery issue for domestic political purposes, but these same domestic issues could have great impact on the French government's decision on recognizing the Confederacy. According to Paul Pecquet du Bellet, a New Orleans attorney who had lived in Paris for several years, “War meant Emancipation.” Even the few “neutral” editors in France blasted the “Southern Cannibals” who feasted on young blacks for breakfast.14

The future of recognition rested largely in the hands of President Davis, of Mississippi, who appeared to personify everything the Old South romanticized itself to be. His administrative, political, and military background suggested wisdom in his choice as chief executive. After graduating from West Point, he fought heroically in the Mexican War, served creditably as secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce, and amassed an enviable record as a U.S. senator. But the image belied the reality. Davis was a distinguished and knowledgeable southern statesman, but beneath the admirable exterior ran an innate, cold aloofness that soon manifested itself in a stubborn, self-righteous attitude rarely tolerant of either criticism or advice. Furthermore, he was so provincial that his experience in foreign policy was limited to his regular reading of the Times. Like his colleagues, however, he firmly believed that cotton would win the allegiance of Britain and other commercial and manufacturing nations.15

Davis joined his cohorts in maintaining that Britain (and France) would recognize the Confederacy within a short time. In Stevenson, Alabama, he glowingly proclaimed his belief that the Border States of Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware (slave states that had not yet decided whether to secede) would soon join the Confederacy and that “England will recognize us.” Consequently, he ignored those few southerners who understood the delicate nature of the recognition issue and cajoled him to appoint a commission of qualified diplomats. Instead, he agreed with those others who boastfully cited both public and private sources that certified the imminence of British and French recognition. In addition to encouraging remarks by the British press emerged other positive signs. John Slidell, former Louisiana senator, wrote a friend that the French minister in Washington, Henri Mercier, felt certain that Emperor Napoleon III would extend recognition and that if the Union government passed a protective tariff, England would surely follow. The most telling fact was that 93 percent of French cotton imports came from the South.16

Armed with these assurances, Davis failed to exercise sound judgment in selecting fiery secessionist William L. Yancey of Alabama to head the three-member commission to Europe. Indeed, the probability is that Davis's dislike for Yancey provided the impetus for sending him out of the country. Whatever the reasoning behind the decision, it was a mistake. Yancey had a history of violent behavior that included killing his wife's uncle over a point of honor. He had been instrumental in writing the Alabama platform in 1848 that fitted nicely with the Dred Scott decision of 1857 in asserting the right of Americans to take their property—that is, slaves—anywhere in the Union and that became the chief divisive element in the collapse of the Democratic Party in 1860. Yancey then capitalized his defense of slavery by ardently advocating a reopened Atlantic slave trade. As for secession, he proved so viscerally supportive of southern independence that moderates had distanced themselves from the man billed by the New York Tribune as the “most precipitate of precipitators.” The British consul in Charleston, Robert Bunch, dismissed Yancey as “impulsive, erratic and hot-headed; a rabid Secessionist, a favourer of a revival of the Slave-Trade, and a ‘filibuster' of the extremist type of ‘manifest destiny.'”17

Yancey's volatile defense of slavery and unquestioned oratorical talents did not appeal to all southerners. Diarist Mary Chesnut recognized that even elegantly worded bombast did not guarantee success in diplomacy. “Who wants eloquence?” she indignantly demanded. “We want somebody who can hold his tongue…. No stump speeches will be possible, but only a little quiet conversation with slow, solid, commonsense people who begin to suspect as soon as any flourish of trumpets meet their ear.” Yancey, she disdainfully concluded, was “a common creature” from a “shabby set” of men.18

Davis demonstrated a comparable lack of thought in appointing Pierre A. Rost of Louisiana and Ambrose D. Mann of Virginia to join Yancey. Rost, a former state congressman from Mississippi, had moved to Louisiana and later became a member of the state's supreme court. It quickly became clear that this elderly, soft-spoken gentleman's only qualifications in foreign affairs were his birth in France and his claim to speak the language. “Has the South no sons capable of representing your country?” indignantly asked one French noble of a Louisianan after hearing Rost struggle with his broken French. Mann, a native Virginian, had attended West Point before becoming disenchanted with the military. He then served as assistant secretary of state, only to resign during the mid-1850s to work for a stronger economic position for the South. His sole distinction, more than a few noted, lay in his mastery of platitudes. Bunch was not even that charitable. Mann was the “son of a bankrupt grocer in the Eastern part of Virginia” and had “no special merit of any description.” Rost, Bunch concluded with fewer words, was a nobody.19

Thus Yancey was the dominant figure among three less-than-impressive commissioners, even though Mann had proven ability in commercial matters and was personally close to Davis. Indeed, the president of the Confederacy effusively praised Mann for “all the accomplishments of a trained diplomat” who had “united every Christian virtue” into a “perfect man.” Rost, meanwhile, failed to make an impression except, perhaps, by his obscurity and weak French language skills.20 Yancey's liabilities, however, far outweighed any assets possessed by his two colleagues. In the meantime, a small band of anxious Confederate spokesmen preferred not to wait for the work of a commission: They sought to force British recognition of the Confederacy by levying an export duty on cotton and creating a shortage overseas. Late in February 1861, Thomas R. R. Cobb from Georgia presented the proposal to the Confederate Congress. A cotton embargo, he argued, “could soon place, not only the United States, but many of the European powers, under the necessity of electing between such a recognition of our independence, as we may require, or domestic convulsions at home.” But Cobb's efforts aroused little support among the majority of congressmen who considered it prudent to await a decision from London rather than alienate its leaders before they had had a chance to act. Even Cobb saw the wisdom in patience. To his wife, he wrote, “The firm and universal conviction here is, that Great Britain, France, and Russia will acknowledge us at once in the family of nations.”21

Everything seemed to be falling into place for the Confederacy, capped on March 2, 1861, when the U.S. Congress raised import duties with the Morrill Tariff. Many northerners warned that the rise in costs would anger the British—and at precisely the time the Confederacy sought recognition. In the debate over the bill, New York congressman Daniel E. Sickles lashed out at his colleagues for provoking the mother country when “all eyes are turned upon the policy which will control European States—whether it is to be the policy of non-interference, or the policy of recognition.”22

In actuality, the higher tariff did not help the Confederacy. When the British learned that Yancey headed the Confederate commission, they turned whatever negative thoughts they had about the tariff to indignation over having to receive what the Times termed three “American fanatics” who mistakenly thought that in Britain “the coarsest self-interest overrules every consideration.” Confederate talk of an export tax on cotton further angered the British. The Times directed its ire at both Union and Confederate officials who, “agreeing on nothing else, are quite unanimous on two things: first, the avoidance of direct taxes on themselves, and secondly, the desire to fix upon England the expenses of their inglorious and unnatural combat.”23

The Confederacy meanwhile experimented with other ways to achieve European recognition. Less than a week after Cobb's abortive call for a cotton embargo, the Confederacy opened its coastal trade and attempted to establish direct commercial and communication links with Europe. Shortly afterward, the Montgomery Congress followed Cobb's recommendation to direct its three commissioners to negotiate treaties with those nations interested in guaranteeing reciprocal copyright protection to all authors. Such an arrangement, Cobb confidently wrote his wife, would “operate strongly to bring the literary world, especially of Great Britain, to sympathize with us against the Yankee literary pirates.”24

The Confederacy's unfounded optimism clouded the reality in its hopes for British recognition. As a veteran of the diplomatic wars, the London government would not take such an important step without considering its impact on the British national interest. Sentiment must never be the guiding principle in international relations; nor could the threat of copyright violations gear the nation into militant action. Cotton likewise failed to provide the leverage for forcing recognition: The British (and French) had such a huge backlog on hand that a southern embargo posed no threat to either European nation's security. The only path to recognition lay in the Confederacy's proving itself a nation not subject to a forced restoration of the Union. Herein lay the Confederacy's central dilemma: Recognition had the potential of assuring independence, but the Confederacy had to convince the European governments of its independence before they would consider recognition. In other words, the Confederacy came to fear that it would get no help from abroad until it required none.

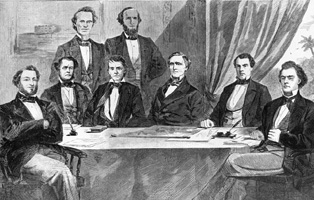

First Confederate cabinet. Seated, left to right: Attorney General Judah P. Benjamin, Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory, Vice President Alexander H. Stephens, President Jefferson Davis, Postmaster General John H. Reagan, Secretary of State Robert Toombs. Standing, left to right: Secretary of the Treasury Christopher G. Memminger, Secretary of War Leroy P. Walker. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

On March 16 Confederate secretary of state Robert Toombs formally provided the commissioners with instructions that further demonstrated the Confederacy's inability to find the leverage needed to extract recognition. They were to assure their host governments that southerners had not violated “obligations of allegiance” in withdrawing from the Union and now sought the “friendly recognition” due any people “capable of self-government” and possessing “the power to maintain their independence.” They were also to negotiate treaties of amity and commerce. The commissioners carried with them, among other items, an essay on states' rights theory and a lecture on the importance of cotton. Inexplicably, they had no directives to seek either foreign assistance or other treaties beyond those assuring commerce and friendship. Toombs presumably considered recognition so much a matter of right that he saw no need to make a formal request. In a mild use of cotton as leverage with England, he instructed the commissioners to make a “delicate allusion” to “the condition to which the British realm would be reduced if the supply of our staple should suddenly fail or even be considerably diminished.” Robert Barnwell Rhett, an outspoken proponent of reopening the international slave trade and highly influential in shaping the views of the Charleston Mercury (edited by his son), advocated a strong economic alliance with England. To Yancey he indignantly snorted: “Sir, you have no business in Europe. You carry no argument which Europe cares to hear…. My counsel to you as a friend is, if you value your reputation, to stay at home or to go prepared to conciliate Europe by irresistible proffers of trade.”25

Rhett's advice, no matter how realistic, never guided the commission's work. Most southerners continued to believe that recognition by Britain and other European powers would automatically take place because of cotton's importance to the Old World's textile industry. Negotiations seemed unnecessary because they could lead only to bothersome obligations incurred by the Confederacy. Such an attitude provides a classic example of how overconfidence can breed naïveté.

The Confederacy raised more false hopes after Lincoln's inauguration as president in March 1861. Repeatedly compared in an unfavorable light to Davis, Lincoln emerged in southern imagery as seriously deficient in physical appearance, dress, intellect, and administrative experience when placed alongside those much heralded qualities of the stately looking president from Mississippi. But what Lincoln lacked in image, he amply possessed in humility, character, sincerity, warmth, wisdom, and sheer common sense. Furthermore, he had a realistic view of the sectional crisis. The tall and gangly Illinois lawyer and former state and national congressman fitted uncomfortably with most of his political colleagues who, throughout their public careers, had drifted behind the shifting winds of political change. Lincoln too had swayed from one side to the other on some issues, but never on the central principle now at stake—the sanctity of the Union. Its preservation became his guiding principle in all deliberations, both domestic and foreign.

Lincoln admitted to having no knowledge in foreign affairs but humbly expressed his willingness to take advice. Unlike his counterpart from the Confederacy, Lincoln did not subscribe to the Times of London, and he was the first to acknowledge that he was a novice in international matters. “I don't know anything about diplomacy,” he confessed to a foreign emissary just before inauguration. “I will be apt to make blunders.” Lincoln consequently relied heavily on his secretary of state, the cosmopolitan former governor of New York and recent rival for the Republican nomination for the presidency, the pugnacious and outspoken William H. Seward.26

William H. Seward, U.S. secretary of state (Courtesy of the National Archives)

Lincoln compensated for his inexperience in international relations by proving himself an innate and consummate diplomatist. What qualities he lacked in formal preparation, he possessed by his very nature. Lincoln was blessed with the essential virtues of a born diplomat: a calm and patient demeanor, a trusting yet careful and genteel temperament, unquestioned integrity, an interest in listening to advice and learning from those who disagreed with him, and a willingness to compromise on issues requiring no sacrifice of principles. Furthermore, he ingeniously related the role of foreign policy to his chief objective of preserving the Union. Stories are legend of his long hours into the night at the War Office, studying battle plans and maneuvers, agonizing over the human costs of both victory and defeat, and wondering what Providence had in store for a nation at war with itself. Not so well known were his many informal conversations with Seward about the dread of British recognition and how, given the precarious balance of the war on the battlefield, such a decision by London virtually assured calamity for the Union.

Lincoln's public focus on the domestic problems underlying the Civil War should not obscure his quiet, yet forceful role in foreign affairs. Most important, he grasped the intimate relationship between the two. Early in his administration, he underlined his intention to head the government in all matters. Seward's dispatches characteristically opened with his acknowledging the president's approval of their contents. Given Lincoln's reserved and nonassuming character, along with Seward's steadily growing respect for his superior, it should come as no surprise that the president became deeply involved in all subjects affecting the Union's welfare. He certainly remained abreast of the diplomatic issues that touched on British intervention in the war.

Seward's appointment as secretary of state testifies to Lincoln's capacity to rise above personal differences for the good of the larger cause. The New Yorker had been so bitter about losing the Republican Party's nomination to Lincoln that he had reconciled himself to a life of sullen political oblivion. But Lincoln recognized Seward's personal capabilities and highly respected position in the party and persuaded him to take the senior seat in the cabinet. Just two days before the inauguration, Seward accepted the appointment, immodestly muttering to his wife that the country needed him in these dire times because of the infinite ineptitude of the incoming president.

As a self-anointed prime minister of the new government, Seward intended to save the faltering country from its new leader by seizing control of both foreign and domestic affairs. He seemed capable. This short, thin man commanded attention in a crowd, even though his most noticeable physical features were his unkempt gray hair, floppy ears, big eyes rimmed by thick, bushy eyebrows, a pale and almost empty complexion, and a long beaked nose that cast a shadow over his recessed chin. But what he lacked in appearance, he made up in experience and, more often than not, a brash, intimidating behavior that he accented by sheer noise. Had he not served with distinction as a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee since 1857? Had he not twice traveled in Europe where, in 1859, he received a royal reception in Britain, albeit because of his expected ascendancy to the Executive Mansion? But he was outspoken and hot tempered, and, particularly after his aggressive role in the Alexander McLeod crisis of the 1840s, he gained the reputation in England of being an avowed Anglophobe who exploited anti-British feeling in America for his own political purposes. This reputation was not entirely undeserved. Britain, he once proclaimed in a calculated exaggeration, was “the greatest, the most grasping and the most rapacious” power in the world.27

Richard B. Lyons, British minister to the United States (Lord Newton, Lord Lyons: A Record of British Diplomacy, 2 vols. [London: Edward Arnold, 1913], 1:frontispiece)

The secretary of state soon took advantage of his fiery notoriety to pursue a dangerous strategy: warning the British and French that any form of interference in the American conflict meant war with the Union. Seward planted stories around Washington that he intended to seek a foreign war to cure the ills of secession by reuniting all Americans—northerners and southerners—under the flag.

The Confederacy found little support from the British minister to Washington, the calm and staid Richard B. Lyons, who had intended to wind down his career in peace but found himself thrust into the apex of a gathering storm in which his own country could play the decisive role. Lyons hated slavery as much as he respected the law and had therefore reacted unfavorably to secession. The British, he wrote his home office, must always oppose “intimate relations with a Confederation formed on the avowed principle of perpetuating, if not extending, Slavery.” Lyons had held this often-caricatured frontier post in Washington since 1858 without recording any mark of distinction more heralded than any upstanding Briton believed the obscure position deserved. Indeed, his appointment had drawn considerable criticism from Americans as further evidence of the British government's insulting refusal to send first-rate diplomats to the United States. Lyons, reserved almost to the point of reticence, acted well under pressure and, as matters became increasingly grim, rose to the occasion and won the respect of those around him. Privately, however, he dismissed most American leaders as petty politicians who continually shifted their positions according to the demands of the mob and did not have the vaguest understanding of right and wrong. But he proved remarkably adept in concealing these feelings. As Britain's chief official source of information in America, Lyons provided well-reasoned and thorough dispatches that carried special weight in London.28

At first, Lyons believed that Lincoln's secretary of state seemed determined to turn the British against the Union. Seward, Lyons declared with disgust, had made a career out of publicly displaying “insolence” toward the British. One contemporary ridiculed him as “an ogre fully resolved to eat all Englishmen raw.”29 But ever so gradually did Lyons realize that Seward was playing a game with the British (and French), a dangerous, high-stakes game to be sure in which foreign recognition of the Confederacy could mean the death of the Union.

Lyons's assessment of Seward was harsh but, in large part, purposely orchestrated by his American host. Admittedly, the secretary's lightning-rod demeanor did not fit the image of a studious and calm diplomatist, but he joined Lincoln in realizing that the central issue in this sectional conflict was the Union's safety and never wavered from its defense. His desperate type of diplomacy rested on war threats intended to convince the British that they should not even think about interfering in American affairs. He knew that the entire Union edifice could collapse if the British intervened and, in so doing, determine the outcome of the contest. Seward used his Anglophobic reputation to cultivate the image of a madman willing to go to war to prevent foreign recognition of the Confederacy. Whether he would follow through on his threats became a critical consideration for British policymakers. Such a provocative strategy seemed fitting in light of their refusal to offer assurances against recognizing the Confederacy and their decision to receive its commissioners, albeit on an unofficial basis.30

In actuality, European politics argued against British involvement in the American Civil War. The London ministry's endemic distrust of the French—in particular, the unpredictable and opportunistic Napoleon III—raised fear that its involvement in America or elsewhere would free him to engage in nefarious schemes wherever possible. Napoleon's interest in reestablishing French holdings on the Continent was legend; his ancestral loyalty drove him to restore a French Empire in the New World that would have the residual effect of enhancing his stature in the Old; his push for building a larger navy and broadening his involvement in the Mediterranean provided ample warning of an emerging challenge in maritime matters that England had long considered its special province. Then came reports in early 1861 of some form of private agreement between France and Russia that threatened to change the balance of power in Europe by healing the wounds of the Crimean War. British involvement in the American crisis could take place only at heavy risk to the empire.31

For both practical and legal reasons, then, the British ministry from the eve of southern secession exercised great care not to antagonize either side in the imminent conflict. As early as May 1860, Lyons had warned his superior in London, Foreign Secretary Lord John Russell, that among northerners “a Foreign war finds favour, as a remedy for intestine divisions.” After Lincoln's election, Lyons emphasized that the ministry avoid “anything likely to give the Americans a pretext for quarreling with us.” As for the Confederacy, Lyons declared, its leaders would probably “establish a low Tariff and throw themselves fraternally into our arms, if we let them.” Still, it would be difficult to lay in the same bed with supporters of slavery who had arrogantly boasted of cotton's importance to Britain. Lyons admonished Russell to follow a policy of “caution and Watchfulness to avoid giving serious offence to either party.”32

But there was a limit to the transgressions the British would bear before feeling compelled to act. They could not quietly accept the Union's recently announced intention to close Confederate ports because, Russell assured his minister in Washington, the move endangered British commerce and therefore had the potential of promoting recognition. Such port closures, insisted the White House, were municipal in jurisdiction and fell within the constitutional authority of the federal government in Washington. The British argued, however, that the action would be international in thrust and thus violate their maritime rights and insult their honor. Furthermore, a Union closure of southern ports would be illegal under international law—a move tantamount to a paper blockade. Port closures had no established procedural guidelines and were subject to abuse; they could force the British to recognize the Confederacy. Indeed, the Union's anticipated policy threatened to push the British and French together. Perhaps this was good, Lyons thought. Knowing that recognition could cause war with the United States, he considered Anglo-French cooperation a wise precautionary measure. He pointedly warned Seward that Union interference with British commerce would force a European involvement detrimental to northern interests.33

Lord John Russell, British foreign secretary (Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society)

As Lyons had predicted, Seward's provocative policy soon drove the British and French together. At a dinner party in late March 1861, the secretary of state sternly advised his guests from the diplomatic corps that their countries' merchant vessels must not enter or leave a southern port without federal authorization. Lyons had earlier that same day alerted his home government to potential Union interference with British commerce, suggesting that “it certainly appeared that the most simple, if not the only way, would be to recognize the Southern Confederacy.” That evening Seward engaged in a heated discussion of maritime rights with Lyons, Mercier, and Russian minister Edouard de Stoeckl, highlighted by the secretary's blunt challenge: “If one of your ships comes out of a Southern Port, without the Papers required by the laws of the United States, and is seized by one of our Cruisers and carried into New York and confiscated, we shall not make any compensation.” Stoeckl, Lyons later reported, objected “good-humouredly” to this stance by contending that a blockade must be effective to be legal. But a port closure was not a blockade, Seward insisted. The Union's problems were domestic, meaning that its ships off the southern coast were following municipal law in collecting duties and enforcing customs laws. Lyons called this a thinly disguised paper blockade and warned that the United States's actions would leave other nations with the choice of either submitting to commercial violations or extending recognition to the Confederacy. If the United States interfered with British commerce, Lyons stressed, “I could not answer for what might happen.” Such interference “placed Foreign Powers in the Dilemma of recognizing the Southern Confederation or of submitting to the interruption of this Commerce.” Seward, by that time braced by whiskey and enveloped by his own cigar smoke, became “more and more violent and noisy,” blasting such a policy with invectives that Lyons related would have been “more convenient not to have heard.” For a moment Lyons lost his composure, just as provocatively apprising Seward that “we must have cotton and we shall have it!” To Russell in London, Lyons recommended that the ministry form a united front with France.34

The image of recklessness fostered by Seward became manifest less than a week later, when rumors of his war-making interest became fact, if only within the deepest recesses of the Lincoln government: On April 1 he handed the president a memorandum calling for war with Europe as a remedy for the threatening conflict in the United States. The administration, he wrote Lincoln, should demand explanations from both France and Spain for their recent interventionist activities in Mexico and Santo Domingo. If they failed to justify these acts, Seward asserted, Congress should declare war on both countries. “I neither seek to evade nor assume responsibility,” he not so humbly noted.35

President Lincoln gave this memorandum the cold reception it deserved on this appropriately timed April Fool's Day. Already concerned about the threat of domestic conflict attracting external interference, he now saw his secretary of state actually invite outside trouble. A risky theory it was to expect Americans from both the Union and the Confederacy to rally around the flag against an alleged greater danger posed by the Old World. What if the Confederates stayed out of the ensuing foreign crisis and left the Union to fend on its own? Seward nonetheless believed Union sentiment so strong in the South that it only needed some cause to become active. Lincoln, however, refused to throw down the gauntlet to Europe and thereby have the Union fight two wars at once. Besides, he suspected Seward of using foreign interference in the New World as a ploy for his seizing control of the cabinet and the administration itself. The president ignored the memorandum, while making clear that if such action proved necessary, he would assume responsibility.36

That dangerous proposition aside, the Lincoln administration now confronted the serious challenge of convincing the British and others across the Atlantic that the conflagration threatening to break out over slavery did not concern slavery after all. This was the central political dilemma facing the president. Although personally detesting slavery, he had supported the Republican Party's platform during the presidential campaign of opposing only the expansion of slavery in the territories and focused instead on preserving the Union. Seward likewise disliked slavery without taking the abolitionist position and emphasized the Union above all. The Confederacy, he argued, needed a gradual emancipation program that afforded time for the region to convert from a slave economy to one based on free labor. Both he and the president also realized that few northerners would fight for black people and that even fewer had any interest in abolition. A crusade against slavery thus carried the triple liability of alienating fellow northerners as well as Unionists in the Confederacy while forcing the four Border States out of the Union.37

The concept of Union and both antagonists' appeals to liberty particularly baffled Europeans. Did freedom have different meanings? How could such an amorphous concept rule out compromise between northern and southern Americans? A range of nationalities had managed to live alongside each other on the European continent; surely so many Americans of similar ancestries could work out their differences. Yet neither the Confederates nor the Unionists could compromise, each side tracing its lineage directly to the Founding Fathers and believing the other had corrupted the republic—the Union with its Hamiltonian principles of centralized government masking its oppressive rule, and the Confederacy pursuing the Jeffersonian ideals of states' rights that clouded its real concern about maintaining slavery. Europeans never comprehended the depth of the differences between the Union and the Confederacy. Both sides considered themselves the true protectors of the American Revolutionary heritage—the Union in preserving the nation from dissolution, the Confederacy in fighting for independence from a tyranny that this time came from Washington, not London.38 From thousands of miles away, Europeans found this conflict difficult to understand. To Americans on both sides, the issues were clear. The North-South differences were irreconcilable because they struck at the very essence of the republic and what it meant to its Constitution, states, and citizens.

The British and other European observers also never grasped the integral relationship between American internal politics and slavery, and when Lincoln pronounced Union rather than slavery as the core issue between the sections, he inadvertently opened the way for outsiders to judge the struggle based on commercial interests. The British no longer had to make the hard choice between upholding their moral commitment against slavery and their need to maintain connections with the Confederacy's cotton distributors. With morality set aside, the chief consideration became trade. Despite “all our virulent abuse of slavery and slave-owners,” wrote one Englishman, “we are just as anxious for, and as much interested in, the prosperity of the slavery interest in the Southern States as the Carolinian and Georgian planters themselves, and all Lancashire would deplore a successful resurrection of the slaves, if such a thing were possible.” This unexpected twist of circumstances replaced conscience with economics in British deliberations and thereby removed a major obstacle to their extending recognition to the Confederacy.39

The Lincoln administration nonetheless considered slavery the root of the Union-Confederate struggle and assumed the British astute enough to recognize the obvious. The new president appointed abolitionists to several foreign ministries, hoping to send a message to those outside the United States that he opposed slavery.40 He believed that the Republican Party's resistance to the extension of slavery guaranteed its collapse. Was not slavery dependent on cotton which, in turn, drained the soil of nitrogen and necessitated a continual search for new fields that someday had to end? Slavery had threatened to tear apart the Union because the sanctity of that institution rested on the divisive doctrines of sectionalism and states' rights. In his Inaugural Address, Lincoln had exalted nationalism in a nearly mystical fashion, declaring his undying faith in the permanence of the Union and promising to destroy any issue threatening its survival. Yet he realized that the law protected slavery and that he could not disturb it wherever it already existed. Nonetheless, both he and southerners recognized that the Republican Party's stand against the spread of slavery meant its “ultimate extinction.” With justification, southerners believed the only way to preserve their way of life was to leave the Union.

By the eve of a nearly certain war, the existence of slavery had forced the development of two sections of Americans, one slave and one free. The American republic, which had tried for years to join slavery and freedom under one banner, found itself too divided on the inside to remain united on the outside. Slavery permeated almost every debate between northerners and southerners, making their exchanges particularly embittered when more than a few observers predicted racial war once four million slaves became free. Such a terrible specter alarmed, among others, Seward, Attorney General Edward Bates, John Hay, Lincoln's secretary, and the president as well.41

Charles Francis Adams, U.S. minister to England (Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society)

The British and many Americans, however, did not understand how deeply embedded slavery had burrowed into the nation's consciousness. Russell in London was perplexed by events in America, lamenting in December 1860 that he could not understand why the northern antislavery majority did not simply outlaw slavery. Americans also failed to realize the depth of the problem. At a White House dinner the following March, several dignitaries almost casually remarked that the Union was about to embark on a war for emancipation and easily dismissed the possibility of England's supporting a southern people attempting to construct a nation on slavery.42

An integral part of Lincoln's attempt to stave off British recognition of the Confederacy was his appointment of Charles Francis Adams of Massachusetts to the pivotal ministerial post in London. Grandson of the famous Founding Father John Adams, the younger Adams was the son of former president John Quincy Adams and enjoyed a well-deserved reputation for his scholarly demeanor, rigid opposition to slavery, and air of genteel self-control that made him appear almost British in manner. “Diplomacy and statesmanship run in his blood,” a Boston newspaper enthusiastically remarked. Both his forebears had served as minister to the Court of St. James's, and his mother's father had been a consul in London. “The first and greatest qualification of a statesman,” Charles Francis Adams declared, was “the mastery of the whole theory of morals which makes the foundation of all human society.” The second was “the application of the knowledge thus gained to the events of his time in a continuous and systematic way.” In temperament, education, breeding, and opposition to slavery, Adams fitted comfortably in British political and social circles. As fate would have it, however, he did not depart for England until May 1, 1861, two days after his son John's wedding but several weeks after the Confederate commissioners had left on their mission abroad.43

By late March 1861 it appeared that British leaders had already made up their minds for recognition when a well-known southern sympathizer in Parliament, William H. Gregory, announced his intention to present a motion for recognizing the Confederacy. War in America, he feared, would hurt British industry. The Morrill Tariff, according to southerners, had convinced the British to act in their own economic interests by welcoming the Confederacy into the community of nations. Henry William Ravenel, a plantation owner and internationally known botanist from South Carolina, privately recorded: “Old prejudices against our misunderstood domestic institution of African servitude … are giving way before the urgent calls of Self Interest.” Cotton was the key to freedom, he believed. Britain's only choice was recognition. Not only did southerners provide a product vital to British mills, but they also offered a market for England's manufactured goods and an invitation to its merchants to conduct the Confederacy's carrying trade in light of the few vessels it had after the estrangement from its northern cousins. The United States had enacted a tariff that would damage the European side of Atlantic commerce, and it now posed a formidable manufacturing and commercial rival to Britain. Self-interest, Ravenel repeated with confidence, was “the ruling power among nations, no less than among individuals.”44

Gregory, however, postponed his motion after it drew little preliminary support. Parliamentary member William E. Forster responded to Gregory's notice with an amendment declaring that “the House does not at present desire to express any opinion in favour of such recognition, and trusts that the Government will at no time make it without obtaining due security against the renewal of the African Slave Trade.” Forster's opposition to any involvement with the Confederacy was not surprising, given his Quaker and antislavery lineage—his father a missionary and his uncle, Thomas Fowell Buxton, a legendary proponent of abolition until his death in 1845. Gregory also encountered resistance from the prime minister, Lord Palmerston, who did not want to invite accusations from America that Parliament was meddling in its affairs.45

British belief in the Union's imminent collapse provided further evidence of their outspoken distaste for a democratic rule in the United States that might set an example for reformers in England. How could Washington hold so many Americans in the Union against their will? The democratic principles so cherished in America had led to its undoing. One hardened British observer virtually spat out the rhythmic charge that “the Yankees are a damned lot and republican institutions all rot.” Adams later lamented that the British reaction to the Union's troubles rested on the “grim spectre of democracy, the ingrained jealousy of American power, and the natural pugnacity of John Bull.” The breakup of the Union, smirked editor Walter Bageot of the Economist, would make Americans “less aggressive, less insolent, and less irritable.” The Times declared with bitter satisfaction that democracy's failure would stand as a stern lesson for “unthinking and unprincipled demagogues” at home—particularly Radicals John Bright and Richard Cobden in Parliament—who demanded a broadened franchise in a move more exemplary of “tyranny than true liberty.”46

American events spiraled into a crisis on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces fired on the small federal garrison stationed at Fort Sumter in South Carolina's Charleston Harbor, sounding the death knell of peace and convincing many British observers of democracy's inherent failings. The London Morning Post joined the chorus of criticism by expressing wonder at American naïveté. “Equal citizenship, popular supremacy, vote by ballot and universal suffrage may do well for a while, but they invariably fail in the day of trial.” Those ill-advised reformers who had set their sights on changing the English constitution should study history to understand why the American republic was about to emulate the fate of Greece, Rome, Venice, and France. They had “all suffered and died from intestine disorders.”47

Yet despite the indisputable advantages at home resulting from the coming American disaster abroad, the press in both Britain and France spoke for many observers both inside and outside of government in asserting that a civil war benefited no one. Admittedly, smugly declared one British magazine, such an internal upheaval justified the wisdom of British political institutions while undermining “the diplomatic influence and external power of the United States.” But if disunion must come, many observers declared, let it come peacefully. Indeed, most of the British and French press soon considered southern independence a fait accompli. Let the South go, urged a British abolitionist. War would be total, which meant “extermination, or a fierce and horrible encounter of long duration.” The Union should allow the South to “quietly secede” and escape complicity with slavery. A war itself would bring emancipation, insisted many abolitionists along with Forster, Bright, Cobden, and the Duke of Argyll from Parliament. By no stretch of the imagination could the Union subdue so many people and seize so much territory. The best the Lincoln administration could achieve was a prolonged occupation of the Confederacy at horrific cost in blood and treasure.48

In the meantime, argued many British spokesmen, the wisest policy was neutrality. A severe time of trial was coming, they darkly predicted. The British secretary for war, the scholarly and usually unruffled George Cornewall Lewis, had long feared a civil war in America that would lead to a servile war disrupting the cotton flow. The loss of southern cotton due to a lengthy war meant devastation of the British textile industry. Potential Union violations of British rights at sea would test their character and threaten national honor. Still, the Times declared, “All we can do is keep aloof.” Calls for neutrality came also from Punch, which appealed directly to Palmerston as the longtime critic of Americans, and from his recognized mouthpiece, the Morning Post, which urged “strict and impartial neutrality.”49

The Union's fate in England rested primarily in Palmerston's hands. Now seventy-six years of age, he had spent most of his public career in foreign affairs, and, although he had lost the spring in his step, he remained vibrant and very much alive. Palmerston's single most driving energy was British self-interest, which he particularly savored when vying against America in either political or commercial matters. During the McLeod crisis of the early 1840s, he as foreign secretary had threatened war with the United States because its laws had brought a British citizen to trial in a New York courtroom. America's democracy he despised as a catalyst to disorder both there and everywhere else—including his beloved hierarchical England. Furthermore, he regarded it as hypocrisy for a nation to espouse equality while opposing British attempts to destroy the African slave trade. Indeed, he more than once considered offering recognition to the Confederacy in exchange for assurances against reopening what he denounced as an ugly, immoral practice. Moreover, America's land-grabbing lust of the 1840s—pitifully disguised and weakly justified by the thinly veneered and self-serving label of “manifest destiny”—threatened British interests both in Canada and Central America. The United States, he had decided years earlier, was like other voracious and growing republics, “essentially and inherently aggressive.” As he explained to Russell (who needed no convincing), when “the masses influence or direct the destinies” of a country, they adhere more to “Passion than Interest.”50

Lord Palmerston, British prime minister (Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society)

British foreign policy officially fell under Russell's control, but its real direction came from Palmerston. As longtime rivals for the leadership of the Whig Party, they had more than once found that one could not rule without the other. In 1859 Palmerston, now head of the recently formed Liberal Party, could not form a government without giving Russell a position. Although differing over many issues in succeeding months, they agreed that British interests were the guiding principle in all matters. Palmerston's hair was thin and white, his walk stooped, and his eyesight fading, but he remained flamboyant, outspoken, and unquestionably in command. Russell was less impressive in demeanor and presence, more reserved, even small and weak in physical appearance. So regularly did he report to Palmerston that a contemporary derisively remarked that “John Russell has neither policy nor principles of his own, and is in the hands of Palmerston, who is an artful old dodger.”51

Yet it is not entirely correct to say that Palmerston dominated foreign policy; his mixed breed of cabinet members dictated that he could not act independently. In addition to appointing Liberal stalwarts to key posts, the prime minister had found it politically necessary to invite Whigs, Radicals, and Peelites into his inner circle of advisers, and they demanded that their adventuresome chief of state keep them apprised of every foreign policy decision. Intervention in the American crisis, if Palmerston ever considered the idea, would take place behind a veritable looking glass held by his colleagues. Most notable among these cabinet members was the politically popular William E. Gladstone, who as chancellor of the exchequer found support not only among the Peelites but, in advocating free trade, a smaller tax load, and reduced government, drew the cheers of Cobden Radicals as well. As guardians of an idealized British order, these scions of a new era of balanced government control refused to permit Palmerston as the perennial sword rattler—now regarded as an anachronism in an age that had passed him by—to roam freely around the world, bullying all peoples in his path. Interference in the American crisis could not take place without his having to go through an inherently wary and highly reluctant cabinet.52

It is likewise clear that Russell was not always the prime minister's obedient servant in foreign affairs and that, as foreign secretary, he was capable of acting on his own. As the person having direct and regular contact with foreign emissaries in London, Russell exerted considerable influence on foreign policy. The Union had expected him to take a strong stand against southern separation and publicly guarantee against recognition. But even though he admitted to favoring the Union's restoration and expressed reluctance to help the Confederacy, he could not be sure of the outcome of the struggle and understandably adopted a safe middle ground. In doing so, he infuriated the Union by refusing to make promises against recognition and insisting that the conflict itself must determine British policy. To southerners looking for the slightest sign of British encouragement, this response furnished great cause for exultation. To northerners keenly sensitive about any indication of British favor for the Confederacy, this stance provided proof of dangerous designs.

Indeed, both Union and Confederacy were correct in their assessments of the foreign secretary. Russell was a Whig in philosophy and a Liberal in party, meshing these two into a position advocating the natural right of oppressed peoples to rebel against established authority. Such a stand had particular appeal once the Lincoln administration declared that the central issue was the Union. To northerners who believed that England saw great advantages in disunion, Russell's bland refusal to guarantee against recognition provided evidence for their worst suspicions. It did not seem coincidental that, less than a week later, Gregory announced his intention to present a motion in the House of Commons calling for recognition of the Confederacy.53

If Lincoln and Seward had devised a strategy of threatening war to prevent recognition, it seemed to be working. Palmerston and Russell had already decided to avoid the appearance of interference in American affairs, but the prime minister and others in high British governing circles could not resist their initial gut impulse to applaud the Union's trial. The battle-hardened prime minister had already grappled with the upstart Americans in numerous diplomatic encounters and now expressed ill-concealed satisfaction with the plight of the “disunited States of America.”54

Especially surprising, though only on the surface, was Argyll's reaction to the possible outbreak of war in America. Fervently opposed to slavery, he considered secession anarchy but thought the breakup of the Union would remove U.S. protection from the evil institution and permit the world's progressive opinion to exert its remedial influence on the wayward Americans. For too long northerners had silently acquiesced in slavery by refusing to act on conscience and destroy the blight afflicting four million black people. Both Union and Confederacy were responsible for impeding the advance of civilization.55

Yet a major irritant in British thinking was the Confederacy's haughty attitude of expecting to prescribe British policy. From his firsthand position as consul in Charleston, Robert Bunch witnessed several southerners' openly expressed delight at seeing how dependent the crown was on their actions and how they wished to embarrass the British as recompense for their longtime criticism of slavery. But Lyons warned Russell that even the poor quality of the three Confederate commissioners must not lead him to turn them away. Such rash action might throw more power to the “violent party” in Washington “who maintained that any measures whatever may be taken by this Government against Foreign Commerce” without causing British recognition of the Confederacy.56

The other side of the argument was Russell's apparent willingness to meet with the southern commissioners, which threw Seward into a rage. “God damn them, I'll give them hell,” he stormed to Senate Foreign Relations Committee chair and friend Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. Having just been privately rebuked by Lincoln over the threat-of-war strategy contained in his April 1 memorandum, the secretary of state was in no mood to countenance even the briefest British flirtation with the rebels. He drafted a strongly worded dispatch to Adams that Lincoln toned down before countermanding Seward's directive to give Russell a copy. The president instructed Adams to keep the dispatch for his eyes only, while using it to guide his discussions with Russell.57

Not to be denied, Seward found another way to get his sharp message to London by sharing his strong feelings with Times correspondent William H. Russell. Two weeks after Lincoln revised the dispatch to Adams, Seward invited Russell into his home. “The Secretary lit his cigar,” Russell recorded in his diary, “gave one to me, and proceeded to read slowly and with marked emphasis a very long, strong, and able dispatch, which he told me was to be read by Mr. Adams, the American Minister in London, to Lord John Russell. It struck me that the tone of the paper was hostile, that there was an undercurrent of menace through it, and that it contained insinuations that Great Britain would interfere to split up the Republic, if she could, and was pleased at the prospect of the dangers which threatened it.” Seward orchestrated his presentation by raising his voice while reading strongly worded passages and pausing after each one for full impact. Russell admitted that the dispatch, if publicly known, would find an appreciative audience among Americans. But, he darkly added, “It would not be quite so acceptable to the Government and people of Great Britain.”58 Seward knew that John Russell was second in importance only to Richard Lyons in shaping the Palmerston ministry's views toward America.

What was in the dispatch? Seward directed Adams that on his arrival in London he was to warn the British that any discussion with the southern commissioners would be tantamount to recognizing the Confederacy's authority to send them. In that event, Adams was to “desist from all intercourse whatever, official as well as unofficial, with the British government so long as it shall continue intercourse of either kind with the domestic enemies of this country.” Any British dealings with the Confederacy would terminate the Union's friendship. British recognition of the Confederacy meant an endless struggle between the Union and the Confederacy over control of the North American continent. “Permanent dismemberment of the American Union in consequence of that intervention would be perpetual war—civil war.” Not only that, Seward made clear, a break in diplomatic relations with England could lead to another Anglo-American war.59

Lincoln may have tempered the dispatch and prohibited its direct delivery to Russell, but he did nothing to stop Adams from sharing Seward's warning with the British. Seward was brash and outspoken; Lincoln was subtle and quietly persuasive. Yet even though their styles were as different as night and day, they worked in close harmony after the debacle over the April 1 war memorandum—both realizing that British intervention in the Civil War would lead France and other European nations to follow and virtually ensure southern independence.

The Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter meanwhile pushed Americans closer to war. Two days after the opening barrage of April 12, 1861, Union forces evacuated the fort, leaving the Confederacy in control of a federal military facility. Within a week, President Davis took the first step toward building a Confederate navy by announcing the licensing of privateers.60 President Lincoln, however, refused to consider the Confederacy a separate sovereignty and threatened to hang as pirates all those engaged in privateering. The showdown at Fort Sumter led four other states—Arkansas, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia—to proclaim secession, raising the number of states in the Confederacy to eleven.

The prospect of the Union surviving this sectional assault struck British observers as inconceivable. As early as New Year's Day of 1861, Palmerston had told Queen Victoria that the Union's dissolution was inescapable. Russell soon thereafter decided that the Union could not be “cobbled together again” by some nebulous compromise and should accept secession: “One Republic to be constituted on the principle of freedom and personal liberty—the other on the principle of slavery and the mutual surrender of fugitives.” Thus would southern independence seal the fate of slavery by isolating slaveowners in a Western world opposed to slavery and surrounded by nations promising freedom to escaping slaves. Contrary to the widespread perception that Europeans considered the United States as the last hope for emancipation, they did so only by default. The British foreign secretary concluded that the differences between northerners and southerners were irreconcilable but that “in a legal sense” the Confederacy was right. The breakup of the Union seemed assured—and not just to observers more than three thousand miles away. Journalist William H. Russell noted little Union sentiment in the Confederacy. A Georgian expressed his people's feelings of invincibility by proudly declaring to the Times correspondent, “They can't conquer us, Sir!”61

British exultation over the Union's troubles sent misleading signals that it supported the Confederacy. The recent southern decision to outlaw the African slave trade did not draw extensive European support; instead, the British spoke for others in denouncing this long-needed move as too conveniently timed—a calculated effort to placate the Border States while pandering to foreign opinion. After his first response, Palmerston soberly warned that a more assertive Confederacy would challenge British interests in Central America and Mexico.62 Such were the underlying truths of the London ministry's position that got lost in the chaotic aftermath of Fort Sumter's collapse.

The Confederacy believed recognition forthcoming when, on April 16, Bunch informed Governor Francis Pickens of South Carolina that Adams in London had failed to secure Lord Russell's guarantee against southern recognition. That this response came just two days after the Confederate victory at Fort Sumter provided further reason to believe the foreign secretary's evasive stand to be a subtle signal of imminent recognition. Even more hopeful was Bunch's assurance to Pickens “that if the United States Government attempted a blockade of the Southern ports or if Congress at Washington declared the Southern ports were no longer ports of entry, … it would immediately lead to the recognition of the Independence of the South by Great Britain.”63

Recognition seemed certain when on April 19 President Lincoln made public his intention to impose a blockade on the Confederacy. In the excitement of the time, hardly anyone read the president's declaration with care and assumed that a blockade instantly went into effect. “I have deemed it advisable to set on foot a blockade,” he announced, signaling his objective of putting it into place. Seward likewise called the proclamation a “mere notice of an intention to carry it into effect.” When established, the blockade would be “actual and effective.”64

The Lincoln administration had taken a dangerous step in announcing a move toward a blockade. International law stipulated that the establishment of a blockade automatically elevated the status of antagonists to belligerents and permitted both sides to deal with neutral nations. But the president wanted the European powers to be aware that the American problems were domestic in nature and that foreign vessels could not enter rebel ports. Doubtless he and his advisers hoped to stall the Confederacy's receiving belligerent status by proclaiming their intention to install a blockade. In the meantime, they could add the cruisers necessary to implement a blockade that commanded the respect of other nations. They knew that the immediate imposition of a blockade made it a paper blockade, which was contrary to international law and sure to constitute a challenge to Britain and other maritime nations to ignore the Union's patrol vessels. More than anything, the Union needed time to expand its navy.

The British reacted in a mixed way to the president's proclamation. Lyons grasped the subtleties in the administration's move. He regarded Seward's notification as “an announcement of an intention to set on foot a blockade, not as a notification of the actual commencement of one.” The London ministry, however, could not risk certain maritime confrontations over long-standing and sensitive questions of search that raised the issue of national honor. It decided to declare neutrality and, in an effort to avoid responsibility for its nationals' possible behavior, issued a warning that if they violated international law or British municipal law, they did so without either government approval or protection.65

The London ministry nonetheless regarded Lincoln's proclamation as the actual implementation of a blockade, thus placing the American struggle within the dictates of international law and thereby establishing the guidelines for a policy of neutrality. Lincoln's words indicated that the blockade process was under way and that the Palmerston government had to act quickly in implementing the British Foreign Enlistment Act of 1819, which prohibited its subjects from any conduct capable of drawing the nation into the American conflict. All nations affected by the fighting must declare neutrality and thereby put into play a whole system of rules governing a neutral's actions.