CHAPTER 3

The Trent and Confederate Independence

[The Union's action was] an affront to the British flag and a violation of international law.

—LORD JOHN RUSSELL TO LORD LYONS, November 30, 1861

We will wrap the whole world in flames!

—WILLIAM H. SEWARD, December 16, 1861

In early November 1861 the commander of the USSSan Jacinto, Captain Charles Wilkes, forcefully removed two southern emissaries, James M. Mason and John Slidell, from the British mail packet HMSTrent and threatened an Anglo-American war that would all but assure the Confederacy's independence. Mason and Slidell had sought to deal a lethal blow to the Union by convincing the British and French to disavow the blockade and extend diplomatic recognition to the Confederacy. But they could not have known how close they came to achieving this objective before reaching Europe.

At about midnight on October 12, 1861, the CSSTheodora steamed out of Charleston Harbor in a rainstorm, hovering close to the coast and a bare two miles from the pale lights of the Union's blockade squadron. Among the vessel's passengers were Confederate emissaries Mason and Slidell, then on a surreptitious voyage to the Bahamas, where they planned to book passage for their final destinations of England and France, respectively. Finding that no British mail steamers went to Nassau, the Theodora headed for Havana, where the two diplomats received a warm welcome and an invitation to stay at a plantation on the island. Mason and Slidell intended to make connections on the Danish island of St. Thomas, which was the British point of departure for the home port of Southampton. From there Mason would travel to London and Slidell to Paris. Their mission: to secure British and French recognition of the Confederacy.1

Mason and Slidell bore instructions that, if consummated in London and Paris, would have granted the Confederacy nationhood status and increased its chances for winning the war. They were to present evidence to the British and French governments that the Union blockade was ineffective and to seek recognition of southern independence as the prelude to negotiating treaties of amity and commerce. To accomplish these goals, the emissaries were to use King Cotton Diplomacy in emphasizing the importance of that product to Europe's textile mills, while convincing the European powers of their opportunity to strike a blow at U.S. commercial competition and to establish a balance of power in North America that protected British and French interests in the hemisphere. As one contemporary southerner proudly put it, “We point to that little attenuated cotton thread, which a child can break, but which nevertheless can hang the world.” So confident was the Confederacy in the righteousness and capabilities of its cause that Mason and Slidell were not to ask for “material aid or alliances offensive and defensive, but [only] for … a recognized place as a free and independent people.”2

President Davis, like European observers from overseas, thought the Confederate rout at Bull Run had assured a rapid end to the war. He therefore moved more directly for European recognition by sending his good friend Mason of Virginia as minister to England and Slidell of Louisiana as minister to France. The Confederacy wanted nothing in return for recognition, Davis told the Congress in Richmond—no assistance and no offensive or defensive treaties—just equal treatment as a nation expecting to engage in commerce with others.3 As with his earlier selection of the three commissioners, however, Davis again underestimated the importance of choosing such key persons with care.

Mason was anything but a diplomat, both by training and temperament. Southern diarist Mary Chesnut angrily blasted his appointment as “the maddest thing yet.” The move was worse than sending Yancey—“and that was a catastrophe.” “My wildest imagination will not picture Mr. Mason as a diplomat. He will say ‘chaw' for ‘chew,' and he will call himself ‘Jeems,' and he will wear a dress coat to breakfast.”4 Although Mason chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee for ten years, he had made a greater mark by defending slavery as the critical foundation of a romanticized Old South. As senator during the turbulent prewar years, Mason had made his name anathema in the North by authoring the hated Fugitive Slave Act of 1850; he followed that action four years later with his support of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which effectively erased the boundaries around slavery by introducing the principle of popular sovereignty. Mason had apparently dedicated his life to keeping black people in bonds as the basis of a presumably superior southern civilization.

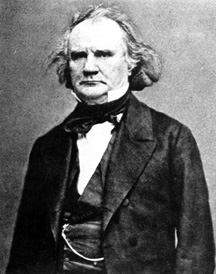

James M. Mason, Confederate minister to England (Courtesy of the National Archives)

Mason's very appearance and demeanor likewise belied any suggestion of a diplomat. From under his thick eyebrows shot a cold glare at anyone who questioned Confederate independence or, for that matter, anything southern. Corpulent and eternally scowling, he had long, scraggly hair that brushed the collar of his coat and cultivated his image of disheveled dress, crude frontier manner, and hot temper. A New York paper called Mason a “cold, calculating, stolid, sour traitor” whose heart was “gangrened with envy and pride, his mien imperious and repulsive.” In the House of Commons, he habitually chewed tobacco and, in the excitement of a debate, more often than not missed the cuspidor in spewing forth a vein of brown spittle that splattered and stained the red royal carpet. “In England,” Chesnut had warned almost prophetically, “a man must expectorate like a gentleman—if he expectorates at all.” Times correspondent William H. Russell thought Mason “a fine old English gentleman—but for tobacco.” Charles Francis Adams Jr. expressed the prevalent view in the Union when he dismissed Mason as a typical Virginian, slow thinking, “very provincial and intensely arrogant.”5

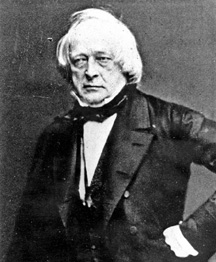

John Slidell, Confederate minister to France (Courtesy of the National Archives)

Slidell was almost equally infamous in the Union. Some years earlier, he had left New York for Louisiana after wounding another man in a duel over a woman. Having found refuge in the Deep South, he established himself as a gambler and lawyer before entering politics. President James K. Polk sent him to Mexico as a special envoy during the tumultuous last days of peace between the nations in late 1845. Rebuffed by the Mexican government, Slidell indignantly called for war as the only policy capable of satisfying American honor against barbarians and, in the meantime, acquiring the lands in the Great Southwest so coveted by the expansionist-minded administration in Washington. As a U.S. senator from 1853 to 1861, he managed James Buchanan's victorious presidential campaign in 1856. Then, on the eve of secession, Slidell established himself as one of the South's most extreme anti-Union spokesmen in Congress. Known as manipulative and clever, he was, according to William Russell, “subtle, full of device, and fond of intrigue.” If thrown into a dungeon, Slidell “would conspire with the mice against the cat sooner than not conspire at all.” Northerners, wrote Charles Francis Adams Jr., considered him “the most dangerous person to the Union the Confederacy could select for diplomatic work in Europe.”6

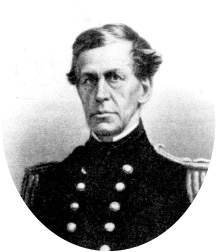

Captain Charles Wilkes of the U.S. Navy (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

If anyone could scuttle Mason and Slidell's mission in Europe, it was Captain Charles Wilkes of the U.S. Navy, a crusty sixty-two-year-old explorer and scientist who had recently assumed command of the San Jacinto, a first-class Union steamer armed with twelve guns and presently patrolling Cuban waters. Stubborn, cocky, irascible, and self-righteous, he was an avid practitioner of gunboat diplomacy who once burned down a village in the Fiji Islands as retribution for their inhabitants having stolen items from his exploring expedition. He also was highly unpopular among his men because of his strict disciplinary practices. Court-martialed in 1842 for illegally punishing sailors, he was acquitted but publicly reprimanded. Wilkes deeply resented the fame and favor long denied him and anxiously sought to make his mark before his not-so-distinguished career came to an end. Perhaps the hot blood of his radical predecessor in England, John Wilkes, still ran in the veins of the ever-cocked descendant. Had not his famed ancestor likewise spurned authority with impunity—the crown itself during the reign of King George III?7

In a characteristic act of independent judgment, Wilkes ignored Washington's orders to head for Philadelphia in late August 1861 and proceeded instead to African waters in search of Confederate privateers. Once there, he heard that Confederate commerce raiders were roaming the West Indies and immediately changed course for the Caribbean. From Cuban newspapers he learned that Mason and Slidell intended to depart Havana on board the British mail packet Trent. This would not happen under his watch, Wilkes so determined.8

On his arrival in Cuba, Wilkes searched for a legal justification for seizing the two southerners from a neutral ship. The U.S. consul general in Havana, Robert Shufeldt, found no precedent for such action in a host of books on international law and finally deemed it “a violation of the rights of neutrals upon the ocean.” But this argument did not stop Wilkes. In his cabin he scoured the works of international law experts James Kent, Sir William Scott (Lord Stowell), Emmerich de Vattel, and Henry Wheaton, and correctly concluded that he possessed the authority to capture vessels carrying enemy dispatches. During the Napoleonic Wars, Lord Stowell from the High Court of Admiralty in England had specifically ruled that ships bearing such papers were subject to capture. But Wilkes wanted to go further and, not so correctly, take the emissaries themselves. He was disappointed with his findings. Mason and Slidell, Wilkes admitted, “were not dispatches in the literal sense, and did not seem to come under that designation, and nowhere could I find a case in point.” But suddenly he found the way. Wilkes reasoned that the two agents were “bent on mischievous and traitorous errands against our country” and, in a strikingly novel interpretation, termed them “the embodiment of dispatches”—hence contraband and subject to seizure.9

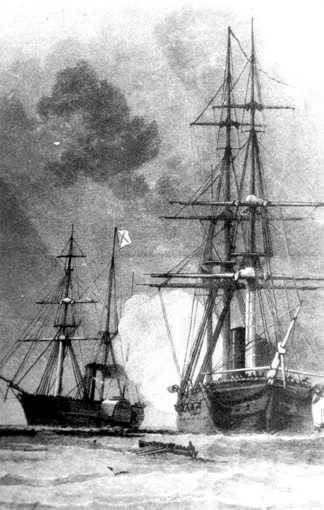

The Trent left Havana on November 7, plying its way along the Cuban coast toward St. Thomas when, a little after noon of the next day, it sighted the San Jacinto 10 miles offshore and 240 miles east of Havana in the Old Bahama Channel. The Union warship fired a single shot across the Trent's bow, signaling an intention to board. But the Trent continued its passage, leading Wilkes to lob a second shot a bit closer to the vessel and bring it to a standstill. As Mason noted the approaching boarding crew armed with guns and cutlasses, he quickly turned over his dispatch bag to the British mail agent, Commander Richard Williams, who locked it in the mail room and promised to complete its delivery to the three Confederate commissioners in London. Mason hid the bag with good reason. It contained official papers of the Confederacy along with the credentials and instructions assigned to the two emissaries. Heading the boarding party was Lieutenant Donald Fairfax, under orders to seize Mason and Slidell, along with their two secretaries and diplomatic papers, and to confiscate the Trent as a prize of war.10

Fairfax, however, encountered unexpected opposition on board the Trent and in the confusion did not follow orders. On declaring his intention to search the vessel, he met fierce resistance from its captain, James Moir. According to one eyewitness, Moir insultingly challenged Fairfax: “For a damned impertinent, outrageous puppy, give me, or don't give me, a Yankee. You go back to your ship, young man, and tell her skipper that you couldn't accomplish your mission, because we wouldn't let ye. I deny your right of search. D'ye understand that?” At this outburst, the sixty passengers (including many southerners) milling around the two parties on deck drew menacingly closer and broke out in raucous applause. “Throw the damn fellow overboard!” shouted one of them. Shaken by the confrontation, Fairfax prudently decided against taking either the Trent or its papers, but he ordered the seizure of the four Confederates. After some pushing and shoving, highlighted by Slidell's fiery wife's threats followed by his futile attempt to escape through a porthole, Mason and Slidell and their two assistants yielded to a mild show of force and became prisoners on the San Jacinto.11

Fairfax's failure to follow orders—combined with Wilkes's surprising approval of his behavior—provided the basis of a major Anglo-American imbroglio over the Trent. In a less-than-convincing defense of his actions, Fairfax explained that since the San Jacinto was about to participate in an attack on Port Royal in South Carolina, it could not spare the sailors necessary to take control of the Trent. Furthermore, its seizure would have inflicted hardship on the passengers and hurt merchants by delaying delivery of the mail and other items aboard. Fairfax's stand was inexplicable. It was absurd to argue—and for a hardened seadog like Wilkes to agree—that wartime decisions rested on whether they inconvenienced civilians. Moreover, Fairfax had no legal justification for assuming that the detachment of sailors to the Trent would have weakened the Union's assault on Port Royal. The U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in The Alexander (1814) and The Grotius (1815) that the assignment of a single sailor to a captured vessel was sufficient to retain a prize if it posed no danger of escape. Finally, Fairfax had the legal right to demand the ship's papers; as Wheaton contended in his treatise on international law, the evidence used in prize court proceedings “must, in the first instance, come from the papers and crew of the captured ship.” Moir's refusal to turn over the papers had revoked the Trent's status as neutral and justified its seizure as a prize.12

HMSTrent and USSSan Jacinto (Courtesy of the National Archives)

In view of these violations of neutrality on board the Trent, Wilkes exercised poor judgment in not seizing the vessel and its papers. In fact, he allowed it to proceed while treating his four prisoners as guests in his cabin en route to their military incarceration at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. Even the most cursory investigation might have uncovered several breaches of neutrality. Captain Moir had resisted a legal search and was carrying enemies of the United States. Not only had Mason conspired with the mail agent to hide his diplomatic pouch, but so had Slidell asked his wife to do the same. According to a newspaper account, just before Slidell disembarked from the Trent, he handed his dispatches to his wife and told her to “sit at the port-hole, and that if an attempt was made to take the box from her, to drop it into the sea. Mrs. Slidell obeyed his orders, was not approached, and took the dispatches safely to England.”13

Wilkes's failure to seize the Trent had opened a labyrinth of legal troubles for the Lincoln administration. His removal of agents claiming protection under a neutral flag had violated the principle of freedom of the seas and insulted British honor. Not realizing the gravity of his error, he boasted to the press that he had acted on his own initiative and proudly declared this “one of the most important days in my naval life.”14

Most Americans learned the fate of the Trent in the afternoon press of November 16; by Monday, just two days later, the northern newspapers almost unanimously praised the capture of Mason and Slidell. A poem greeted Wilkes upon his arrival in Boston on November 25:

Welcome to Wilkes! who didn't wait

To study up Vattel and Wheaton,

But bagged his game, and left the act

For dull diplomacy to treat on.15

The only newspapers with a national circulation were in New York City, and they joined others throughout the Union in approving Wilkes's actions as a justifiable response to the arrogant maritime practices followed by the detested British. The New York Times, typically the voice of moderate Republicans, endorsed his move as falling within the dictates of international law and insisted that the British would not retaliate. As for Wilkes, “Let the handsome thing be done, consecrate another Fourth of July to him.” Horace Greeley's New York Tribune blasted Mason as a “degenerate son” who possessed a “brain composed of the muddiest materials” and Slidell as a “sly, cautious, dark unscrupulous traitor” known best for his “furtive glances and sinister visage.” Moreover, according to Greeley, Wilkes's actions were “in strict accordance with the principles of international law … and,” he sardonically added, “in strict conformity with English practice.” He welcomed a British demand for the release of Mason and Slidell, for this act would signal the crown's acceptance of neutral rights. The Anglophobic New York Herald, which reached readers all over the country along with many in Europe, expected the White House to disavow Wilkes's actions and apologize, but did not advocate returning the captives.16

Several notable Americans commended Wilkes. The U.S. district attorney for Massachusetts, Richard Henry Dana Jr., who wrote the classic Two Years before the Mast and a book on maritime law, vigorously applauded what he regarded as a legal seizure of the southern emissaries. Former minister to England and secretary of state Edward Everett triumphantly cited Lord Stowell's 1813 admiralty court decision (the Anna Maria) defending a belligerent's right to “stop the ambassador of your enemy on his passage.” Indeed, the magistrate had asserted that “in the transmission of dispatches may be conveyed the entire plan of a campaign, that may defeat all the projects of another belligerent in that quarter of the world.” Adam Gurowski, a U.S. State Department adviser who taught international law at Harvard, considered Mason and Slidell a threat to the United States and thus subject to removal from a neutral vessel. As rebel emissaries, they were “political contrabands of war going on a publicly avowed errand hostile to their true government.” These “traveling commissioners of war, of bloodshed and rebellion,” were on a mission to destroy the United States and could not claim diplomatic immunity on board a neutral vessel.17

The Lincoln administration, already under siege after the Union's disastrous defeat at Bull Run, had a mixed but generally favorable reaction to the seizure. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles enthusiastically approved but warned that Wilkes's decision not to take the Trent could set a dangerous precedent. Also supporting Wilkes's action, Seward could not conceive of releasing the captives. The president, however, was deeply concerned about British retaliation. Whether or not Wilkes was legally correct, trouble with England was unavoidable—and at a time when the Union could least afford another enemy. It was satisfying to kick the British lion—but not at the cost of war. While Washington's residents celebrated, Lincoln allegedly told two visitors: “I fear the traitors will prove to be white elephants.”18

From Boston, Senator Charles Sumner, who was chair of the Foreign Relations Committee and well versed in international law, privately disagreed with the exuberant American reaction to the Trent affair. The United States would have to surrender the captives, he believed, but he kept his views quiet out of concern for his position and a wish to avoid further entangling the situation for the White House.19

The strained context in which the seizure took place helps to explain the wildfire of exultation that spread throughout the Union. After the humiliation at Bull Run, the Union was starving for a victory. That the Trent incident came at the expense of the British provided great satisfaction to northerners still infuriated with the queen for proclaiming neutrality and bestowing belligerent status onto the Confederacy. At a public banquet in Boston held in Wilkes's honor, Governor John Andrew crowed that the captain had “fired a shot across the bows of the ship that bore the English lion's head.” The House of Representatives thanked Wilkes “for his brave, adroit and patriotic conduct in the arrest and detention of the traitors.”20

The southern reaction was equally ecstatic but, of course, for different reasons: Wilkes's seizure of Mason and Slidell had encouraged a war between the Union and England that would all but ensure Confederate independence. Whether or not the British formally aligned with the Confederacy, the result would be the same—two nations fighting the Union. The Southern Confederacy in Atlanta cheered Wilkes's action as “one of the most fortunate things for our cause.” The New Orleans Bee happily summed up the Union's dilemma: To release the captives would divide the Union; to refuse would alienate the British. The Bee confidently predicted British recognition of the Confederacy.21

Southern officials in Richmond could barely contain their excitement. President Davis told the Confederate Congress that the Lincoln administration had violated maritime rights that were “for the most part held sacred, even among barbarians.” Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin echoed the New Orleans Bee, smiling while calling the incident “perhaps the best thing that could have happened.” The secretary of the navy, Stephen R. Mallory, expected immediate recognition by the European governments. The Lincoln administration, beamed Secretary of State Robert M. T. Hunter, could not possibly justify “this flagrant violation” of international law and “gross insult” to the British flag. The London government would surely “avenge the insult,” he asserted while directing his three commissioners in London to lodge a formal protest with the Palmerston ministry.22

Because the Atlantic cable was not functioning at this time, it took about two weeks for news to cross the ocean. But when the steamer bearing the story reached England in late November, the result was a firestorm of anger. Elated by the events, Yancey, Rost, and Mann registered the Confederacy's protest with Lord Russell, denouncing Wilkes's action as a transgression of international law. Mason and Slidell had traveled under the protection of the British flag, and the admiralty court should facilitate their release. Not by coincidence did the commissioners simultaneously send Russell a list of those vessels that ran the blockade, arguing that it was a paper blockade and therefore a violation of the Declaration of Paris. Unless the Union made restitution, later reported Rost back in Paris, “war is certain.” The French supported the Confederacy, he noted, “making recognition more likely.” For the moment, they chose to wait for the Union's response to British demands before formally requesting recognition. Mann, however, thought the move imminent. Ever ebullient, he noted that “British officers met me like brothers, conversed with me like brothers. I already esteemed them as allies.”23

Just after noon on November 27, news of the Trent affair reached the American legation in London. Shouts of joy came from the three secretaries, restrained only by Adams's acerbic assistant secretary, Benjamin Moran, who feared the worst. Seizure of Mason and Slidell, Moran wrote in his diary, “will do more for the Southerners than ten victories, for it touches John Bull's honor, and the honor of his flag.” Adams's son Henry moaned that “all the fat's in the fire.” England “means to make war.” The senior Adams agreed with this dire prognosis. Visiting a friend in the countryside when hearing of the Trent, he raced back to London in a state of despondency, only to undergo further discomfiture on having to admit to Russell—then rushing into an emergency cabinet meeting—that Seward had sent no information on the matter. Adams hurriedly completed various tasks of the legation before his expected recall. “The dogs are all let loose,” he glumly confided to his diary.24

War seemed unavoidable. “There never was within memory such a burst of feeling,” wrote an American in London to Seward. “The people are frantic with rage, and were the country polled, I fear 999 men out of a thousand would declare for immediate war.” From Edinburgh came another American's confirmation of the martial spirit sweeping the kingdom: “I have never seen so intense a feeling of indignation exhibited in my life.”25

The Palmerston government interpreted the recently arrived dispatches from the usually soft-spoken Lyons to mean that the United States wanted war. The Americans were “very much pleased at having … insulted the British Flag,” the minister observed as he uncharacteristically urged a show of force to dampen this fiery mood—perhaps a military buildup in Canada and the dispatch of more warships to the British West Indies? Palmerston was furious. At the emergency cabinet meeting on November 28, he reportedly opened proceedings with a veritable declaration of war: “I don't know whether you are going to stand this, but I'll be damned if I do!” Wilkes, Palmerston told the queen, must make reparations for his affront to the British flag. To Russell, the prime minister hotly insisted that his government would not shrink before this “deliberate and premeditated insult” intended to “provoke” a conflict. Russell dryly warned that the Americans were “very dangerous people to run away from.”26

Most British seemed to welcome war. The London Morning Post, so often speaking for Palmerston, firmly believed in rapid victory. “In one month,” it confidently predicted, “we could sweep all the San Jacintos from the seas, blockade the Northern ports, and turn to a direct and speedy issue the tide of the war now raging.” Even the usually staid secretary for war, George Cornewall Lewis, promised that “we shall soon iron the smile out of their faces.” A refusal to surrender Mason and Slidell meant “inevitable war.”27

Other members of the cabinet believed war inescapable. Although pro-Union, the Duke of Argyll told his colleagues that Wilkes's action constituted a violation of international law that Seward had surely instigated. Wilkes's “inconceivable arrogance” was the natural outgrowth “of a purely Democratic govt” that would not “dare to acknowledge itself in the wrong.” Lord Stanley attributed the certainty of war to “the mob of America” that opposed Mason and Slidell's release.28

The British government did not relish a war with the United States but had to prepare for one. It needed a massive number of British troops to defend Canada against an expected U.S. invasion that could come from myriad points along the long frontier stretching from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes. British commerce would fall prey to American privateers, the Union could build more ironclads capable of decimating Britain's wooden vessels, and the chances of conquering the United States were virtually impossible. Seward's longtime heated threats of war had caused a major debate in England over the necessity of building up its defense forces in North America. The British naval squadron commander on the North American and West Indian station, Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Milne, had served the Royal Navy for four decades and knew that his fourteen vessels could not cope with the Union navy. British efforts to defend their North American possession became so extensive in early December 1861 that on one Sunday evening workers loaded enough boxes of firearms to fill eight barges on the Thames River.29

British anger over the Trent affair was intense, and the expected lack of French support did nothing to reduce the hostility. The two countries' relations had sharply deteriorated soon after their victory over Russia in the Crimean War of the mid-1850s, leaving Palmerston deeply apprehensive about a French assault on a number of British stations. Had not Napoleon III reportedly announced in January 1861 that he would make war on England if French public opinion demanded it? Just two years earlier a special study committee in England predicted that by the summer of 1862 the Royal Navy would become second to that of the French. Before the Trent affair, Palmerston had told the queen that Napoleon regarded the Anglo-French concert as “precarious.” The Earl of Clarendon groused that the French emperor would “take this occasion to make us feel that he is necessary to us and to avenge his griefs against us by causing us to eat dirt or go to war with the North with France against us or in a state of doubtful and ill-humoured neutrality.” He warned, however, that peace “never can be worth the price of national honour.”30

Reaction outside the Palmerston ministry was similarly warlike. Britain's lord chief justice declared: “I must unlearn Lord Stowell and burn Wheaton if there is one word of defence for the American Lieutenant…. How a great and gallant nation can en masse confound safe swaggering over unarmed and weak foes with true valor, I cannot understand.” A highly respected British barrister, Edward Twisleton, assured Lewis that Washington's leaders would “submit to almost anything rather than surrender their prisoners. Their false point of honor would not be so much towards England as towards the South; as they would feel humiliated and mortified beyond expression, if having had two of the Arch-rebels in their keeping three weeks and more, they should be afterwards constrained to release them.” Mason and Slidell's capture exasperated British historian George Grote. “What a precious ‘hash' these Yankees are preparing for themselves! Their stupid, childish rage against us, seems to extinguish all sense, in their braggart minds, even where the instinct of self-interest ought to supply it.”31

Not everyone called for war. Two of the ministry's staunchest opponents in the House of Commons, Liberals Richard Cobden and John Bright, refused to believe that the United States wanted conflict. Cobden urged Bright to “expose the self-evident groundlessness of the accusation made by some of our journals that the North wish to pick a quarrel whilst fighting a life or death struggle at home. The accusation is so utterly irrational that it would be regarded as a proof that we want to take advantage of their weakness and to force a quarrel on them.”32

Less than a week after writing Lewis, however, Twisleton curiously reversed his stand on Wilkes and now thought the American captain had acted in accordance with previous British admiralty court decisions during the Napoleonic Wars. In a second letter to Lewis, Twisleton pointed out: “It would seem to have been our principle in 1806 that a belligerent might seize any of his enemies on a neutral vessel, without taking them before a prize court.” Wilkes had “not gone beyond” this standard. Even though Twisleton doubted the wisdom of these rulings, they raised serious questions about whether it would be “a strong measure” for England to declare war “at once” if Lincoln defended the legality of Wilkes's action.33

In the tumult on both sides of the Atlantic, only a few learned observers had the presence of mind to question whether Wilkes had acted in line with the law of nations. Natural law, of course, is the basis of international law, which means that the most basic principle in relations among nations is the right of self-defense or national preservation.34 As Wilkes argued, and as Gurowski in the United States and Twisleton in England concurred, Mason and Slidell were avowed enemies of the Union whose mission was to secure European assistance in a war against that very Union. Wilkes's argument would have been difficult to refute had he identified the two men as emissaries of a belligerent (on board a neutral vessel) whose objective was to secure foreign help (from that same neutral country and others) in a war seeking to destroy the United States. Instead, he fogged the matter by calling them the “embodiment of dispatches” and hence contraband, when he would have stood on fairly sound legal footing by emphasizing self-defense.

The problem, of course, was that the White House could not make a decision outside the Civil War's context. The president could either support Wilkes and risk war with England while also at war with the Confederacy, or renounce the capture and experience a national humiliation that had the saving grace of permitting the Union to concentrate on defeating the Confederacy. In this instance of civil war, arguable legalities became secondary to practical realities. Clarification of the options just as readily clarified the ultimate choice of having to free the two men—if the Union could devise a face-saving retreat.

The British government's primary complaint focused on Wilkes's failure to take the Trent as a prize. In response to Russell's inquiry, the law officers stated that the Americans had violated international law and owed reparations. That information in hand, Russell spent the entire morning of November 30 drafting two dispatches calling for a seven-day ultimatum that he put before the cabinet that afternoon. A heated discussion ensued, during which Earl Granville urged the ministry to leave room for the United States to make an honorable retreat. Gladstone thought Russell too combative in calling for Lyons's departure after seven days if the Union refused to meet British demands. Lewis doubted that the Lincoln administration had ordered the seizure of Mason and Slidell but believed it would refuse to make reparations. The cabinet retained the one-week ultimatum.35

Russell delivered the dispatches to the queen, who turned them over to her consort, Prince Albert, for consideration. Although on his deathbed, he worked much of that night in Windsor Castle to tone down the wording of Russell's first dispatch without altering the demands for the captives' surrender and an apology within seven days. Wilkes's action, the revised version declared, was “an affront to the British flag and a violation of international law.” But Prince Albert, in line with Granville's appeal, left the Union a graceful way out of the crisis. The British government hoped that Wilkes “had not acted under instructions, or, if he did, that he misapprehended them.” On that basis, it expressed confidence that the Lincoln administration would “of its own accord offer to the British Government such redress as alone would satisfy the British nation, namely the liberation of the four Gentlemen … and a suitable apology for the aggression which has been committed.”36

War still seemed likely. Lyons had one week to await Seward's reply. In the meantime, he was to keep Admiral Milne informed about any sign of an American assault on British holdings in North America. If his government did not comply with the demands, Lyons was to pack up his legation personnel and papers and head home. “What we want,” Russell told his minister, “is a plain Yes or a plain No to our very simple demands, and we want that plain Yes or No within seven days of the communication of the despatch.” But Russell left some flexibility in the ultimatum. If Lyons thought the White House was attempting to meet the demands, he could remain at his post beyond the seven-day limit. The times seemed ominous as the U.S. stock market plunged and the British government, noting that Americans were purchasing great quantities of saltpeter (the main ingredient in gunpowder), imposed an immediate embargo on all shipments to the United States.37

The British cabinet considered the Trent affair serious enough to create, for only the fourth time in the nation's history, a special War Committee. Composed of Palmerston, Russell, Lewis, the Duke of Newcastle in the Colonial Office, and other notables, the new committee focused on protecting Britain's North American possessions—particularly Canada—by dispatching more soldiers and bolstering Milne's fleet. Newcastle had received requests for assistance from Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia in constructing an intercolonial railway to help safeguard them from American invasion. In accordance with Lyons's recommendation, the British government prepared to take all necessary steps toward ensuring Union compliance with its demands.38

The Palmerston ministry clung to neutrality in the face of a growing popular clamor for war. Russell responded to the three southern commissioners' call for recognition with another affirmation of British neutrality, but his stand did not diminish their expectations. The Bee-Hive of London, whose editor supported the Confederacy because of the Union's restrictive commercial policies, urged the government to break the blockade to secure cotton and ally with France in a war against the Union. Slavery should pose no obstacle. An independent South, the journal argued, would have to accept emancipation once encased by free territory. William S. Lindsay, a shipping magnate and perhaps the Confederacy's strongest supporter in Parliament, called for an offensive and defensive treaty with the Confederacy before England and the Union went to war.39

Meanwhile, the French stridently condemned the Union's seizure of Mason and Slidell. Nothing, Dayton declared with concern, had matched the “outburst” of anger in his host country. If the United States did not renounce that action, “the almost universal impression here is that war will follow.” Dayton had thought the French would stay back and let the British and Union “fight it out!” But France needed cotton, and the nation's industrial interests might push its government to intervene. Some of the French press wanted the emperor to act with England on the issue. The French joined other Europeans in believing the Union had no respect for international law and had tried “to pick a quarrel” with England.40

Dayton had learned from what he considered a reliable source, the pro-Union Baron Jacob Rothschild of the French banking House of Rothschild, that Thouvenel had told the British minister in Paris that the seizure of Mason and Slidell was “an unwarrantable act” and “a gross violation of international law.” The baron thought that if England recognized the Confederacy, France would follow. But he was certain that “France will not go with us” if war broke out with England. The French “will sympathise (if not act) with Great Britain.” That same day Dayton met with Thouvenel, who termed the Union's action a threat to all maritime powers. If war broke out between England and the United States, the French would be “spectators only,” Dayton declared before adding, “not indifferent spectators.”41

France had surprised the British by taking their side in the Trent crisis and repeating its earlier call for joint intervention. The Union's violation of international law, Mercier told Washington, had obligated his government to take a stand for neutral rights. France expected the White House to refuse to return the captives and planned to recognize the Confederacy in the event of an Anglo-Union war. Outside intervention might resolve the matter before it reached this dangerous point.42

Mercier assured Lyons that joint intervention would work if it included Russia, a friend of the Union. Admittedly, the Russians still harbored ill feelings from their defeat in the Crimean War and remained deeply suspicious of their Anglo-French rivals' imperial ambitions. But the tsar would surely see that everyone would benefit from an end to the American war. Both the British and the French became Russia's suitors, leading its foreign minister, Prince Alexander Gorchakov, to complain about how difficult it was to maintain an impartial stand. “I am sought after everywhere I go, even at the theater, and I have to dodge these attacks by all sorts of little tricks.”43

Lyons, however, doubted that the Union would approve any type of foreign intervention. Perhaps, Mercier reasoned, the time was right for a joint “intimidation” of the Union. Only if not a bluff, Lyons responded. “Otherwise,” he wrote Russell in London, “we shall only weaken the effect of any future offer, by crying out Wolf now, when there is no Wolf.” The Union must realize that rejecting intervention entailed “serious consequences.” The blockade was the non-negotiable issue, Lyons argued. The Union could not win the war without the blockade, whereas the Confederacy would never consider an armistice until the Union abandoned the blockade. Furthermore, Lyons noted darkly, Lincoln had become so desperate that he intended to stir up a slave rebellion and race war by announcing emancipation. War with the Union would place the intervening powers on the side of the slaveholding Confederacy.44

Despite the appearance of French support, the British suspected that Napoleon wanted an Anglo-Union war to boost his country's interests. Lewis felt “quite certain” that the French thought such a war would force the Union to lift the blockade and give them access to southern cotton. Britain's ambassador in Paris confirmed these beliefs. French defense of neutral rights, Lord Cowley stated, was purely expedient. They hated the British “cordially and systematically” and were “behaving well and backing us up nobly” in the event of a war with the Union that opened southern ports and made cotton available. Russell scrawled on the back of Cowley's missive that he was “quite sick” of French “intrigues” against Britain.45

Russell's exasperation with the American war, however, outweighed his concern over Napoleon, who uncharacteristically acted with restraint. Several factors guided the emperor's self-control, including his present involvement with British and Spanish military forces in Mexico, his wish to avoid a confrontation with the Royal Navy, and the widespread popular support in France for the British position in the Trent crisis. In the meantime Russell became fairly confident that the United States did not want war with England, which, paradoxically, kindled his anger because he suspected Americans of wishing to embarrass his government. Nearly “all the world is disgusted by the insolence of the American Republic,” whose people would “like to draw in their horns and be disagreeable to us at the same time.” All we want, he wrote Cowley, was that Lincoln “send our passengers back.” The president had suggested a preference for peace when he did not mention the Trent in his annual message to Congress, but politics often prevailed over principle and even good sense in America, Russell knew, and congressmen owed their positions to being good politicians. The American press was easing its fire, perhaps finally realizing that “the best, if not the only chance of subduing the South is to keep Europe—i.e. England and France neutral.” In a bitter twist of irony, the Union's military leaders seemed more interested in peace than did its civilian counterparts. General George B. McClellan, Russell learned, told Lincoln that Wilkes had had no justification for seizing Mason and Slidell. “I wish McClellan could be made Dictator.”46

The French were among the Europeans in general who joined England in condemning Wilkes's action as an infringement on the rights of all nations at sea. Despite Russia's hatred for England and France, it could not defend the Lincoln administration in this matter. The Union's minister to Belgium, Henry Sanford, informed Washington that most Europeans wanted France to mediate the dispute.47

Even the most patriotic northerners must have realized that war with both the Confederacy and England was unthinkable—but they also understood the importance of salvaging national honor. How could the Union placate the British without backing down? In mid-December Senator Orville Browning was in the president's office when Seward burst in with England's demands. The Union's worst fears had materialized. To surrender the captives and grant an apology constituted an embarrassing retreat magnified by an admission of guilt—and to the British of all peoples. War or humiliation—that was the choice. Browning denounced the British for considering “so foolish a thing” as war. But if England wanted to start one, he even more foolishly exclaimed to Lincoln and Seward, “We will fight her to the death.”48

Signs of war loomed everywhere in the Union. The day after the White House learned the British position, Congress angrily debated whether to redeem the country's honor by keeping Mason and Slidell in captivity, or to undergo national humiliation by capitulating to England's demands. At a dinner party that evening at the Portuguese legation, Seward appeared to prefer the preservation of honor—and the certainty of war. Physically and emotionally exhausted, the secretary of state cut loose a tirade of highly charged remarks as he interchanged downs of brandy with deep draws from his cigar. To an apprehensive group of listeners barely discernible in the smoke-filled room, he self-righteously proclaimed: “We will wrap the whole world in flames!” Times correspondent William Russell stood among the ring of stunned observers, visibly shaken by Seward's loose-winded threats. Seeing his distress, another guest tugged Russell aside to assure him that Seward had only played to his audience: “That's all bugaboo talk. When Seward talks that way, he means to break down. He is most dangerous and obstinate when he pretends to agree a good deal with you.”49

The atmosphere in both Atlantic countries had nonetheless become so raw that mistaken perceptions of motives by either side could set off a war that only the Confederacy wanted. Charles Francis Adams Jr. anxiously wrote his brother in London that the Lincoln administration had “capstoned” its “blunders by blundering into a war with England” that would ensure southern independence. Henry Adams blasted the American reaction at home as incomprehensible. “What a bloody set of fools they are! How in the name of all that's conceivable could you suppose that England would sit quiet under such an insult. We should have jumped out of our boots at such a one.” The United States, he declared to his brother with heightening disgust, had adopted England's contemptible search policies. “Good God, what's got into you all? What in Hell do you mean by deserting now the great principles of our fathers; by returning to the vomit of that dog Great Britain? What do you mean by asserting now principles against which every Adams yet has protested and resisted? You're mad, all of you.”50

And through this dark period, the senior Adams dourly sat in the funereal atmosphere of his legation office, dreading the near certainty of war while lamely awaiting instructions from Washington that did not arrive until mid-December. Until that time, Henry Adams snorted with indignation, his father felt so defenseless that if he saw Lord John Russell walking down the street, he would “run as fast as he could down the nearest alley.” Finally, on December 16, word arrived from Seward that Wilkes had acted without authorization. The minister's immediate sense of relief lasted no longer than it had taken to envelop him. Was it too late to make amends? A few days before Christmas, he noted war preparations in London and warned Seward that failure to comply with their demands meant the British would recognize the Confederacy and refuse to respect the Union's blockade. Little hope for peace rested in Seward's ominous directive authorizing Adams to put the Palmerston ministry on notice that recognition of the Confederacy meant war with the Union.51

Adams feared that the time had passed to avert war without enduring a loss of face. But neither party in the crisis seemed capable of initiating a settlement. His own government had not kept its representative in London well informed. What response could he make to Russell's repeated inquiries about American policy? What peace assurances could he offer? British leadership also seemed lacking. “Where is the master to direct this storm?” asked Adams in disbelief. “Is it Lord Palmerston or Earl Russell?” Seward's angry rhetoric had been nothing more than bluff, Adams knew, but his innate gift for drama had finally convinced the British that he preferred war as the first instrument of diplomacy. Adams wrote his namesake that most British thought Seward “resolved to insult England until she makes a war. He is the bête noire, that frightens them out of all their proprieties. It is of no use to deny it.” Lyons had become a believer, and his dispatches easily validated the tenets of an already-converted ministry at home. War was not a viable option, Adams insisted. The White House must disavow Wilkes's action and surrender the captives. “I would part with them at a cent apiece!”52

British recognition of the Confederacy seemed irrefutable as the Trent furor combined with another hot issue—the growing popular clamor for running the Union blockade. A mid-December issue of the Boston Courier carried Henry Adams's account of his recent visit to Manchester, England, where merchants joined a newspaper editor in urging the government to challenge the blockade and recognize the Confederacy if the American war continued into the spring of 1862 and threatened the cotton flow. At the moment, according to Union supporters Cobden and Bright in Parliament, Lancashire's textile mills had sufficient cotton to temper the growing demand for breaking the blockade. But they had to admit that in the previous November 1861 almost two-thirds of 172,000 workers in 836 textile mills were on short time and another 8,000 had been released. Running the blockade, Bright warned, “would be an act of war.”53

Additional pressure to defy the blockade came from British merchants, who had become incensed over the Union's decision to sink old ships laden with heavy stones (the “stone fleet”) in order to close the channels into southern ports. Although Russell in England knew that international law allowed such action as long as the damage was not permanent, he—and even Cobden—considered the policy barbaric. Seward defended the action as only temporarily injurious and integral to the success of the blockade. The Union left two channels open to Charleston for shipping goods necessary to survival, but the ensuing controversy further heated Anglo-American emotions.54

To the Confederacy, the time seemed propitious for recognition. Its three commissioners in Europe assured their home government that England and France would demand that any settlement require the Union to lift the blockade. They became so excited about impending recognition that they rushed to London and Paris to be present when Palmerston and Napoleon made the announcement.55

Yancey was a bit more guarded in his enthusiasm than were his two companions. The British government, he reported, thought the possibility of war and peace “about evenly balanced.” It had sent ten thousand troops and considerable war materials to Canada, and it had prepared a “great steam fleet.” If war developed, “the English blows will be crushing on the seaboard.” France, he thought, might press Britain into action. Public opinion favored the Confederacy, and when Parliament assembled, Yancey felt certain that the ministry would have “to act favorably or to resign.”56

In the midst of this warlike atmosphere on both sides of the Atlantic, Lyons discerned a subtle but critical change within the Lincoln administration: It seemed less defiant after he formally presented his government's demands on December 23. The British minister had actually delayed this delivery a few days to allow a small passage of time that might ease tempers, and the strategy seemed to have worked. Indeed, he suddenly felt optimistic about White House compliance. That evening he wrote Russell that Seward was

on the side of peace. He does not like the look of the spirit he has called up. Ten months of office have dispelled many of his illusions. I presume that he no longer believes in … the return of the South to the arms of the North in case of a foreign war; in his power to frighten the nations of Europe by great words; in the ease with which the U.S. could crush rebellion with one hand and chastise Europe with the other; in the notion that the relations with England in particular are safe playthings to be used for the amusement of the American people.

Seward faced the “very painful dilemma” of either bearing “the humiliation of yielding to England” or becoming “the author of a disastrous Foreign War.”57

Russell nonetheless had misgivings about the manner and timing of the Lincoln administration's compliance to the demands. “I am still inclined to think Lincoln will submit,” the foreign secretary lamented to Palmerston, “but not till the clock is 59 minutes past 11.”58

The Lincoln administration found itself alone on the Trent issue and compelled to consider a retreat that somehow saved its honor. On Christmas Eve, Dayton confirmed the Union's fears of war with both England and France. The British, he wrote, were continuing military and naval preparations for war and would take the offensive. They had sent supplies to Gibraltar for warships coming from Malta that would then go to the United States. Their Mediterranean fleet would soon be in position to capture U.S. merchant ships in the area—perhaps more than eighty in the French port of Havre alone. Everyone assumed war unless the Union made reparations. The French government did not want war, but it sympathized with the British position and was concerned about breadstuffs if war interrupted crop growth in the United States. Supplies from the Baltic, the Danube, and the Black Sea would not be sufficient. But France would place priority on securing cotton and take its chances on wheat. Above all, the emperor would act in accordance with French interests. Dayton's note did not arrive until sometime afterward, but Mercier informed Seward the same day he received England's demands that Washington had no support from other nations. The French, Mercier emphasized, would not help the Americans.59

In a move that starkly demonstrated how seriously President Lincoln regarded the matter, he invited Sumner to meet with him and the cabinet at 10:00 A.M. on Christmas Day to explore the possibilities of preserving both peace and honor in resolving the crisis before the December 30 deadline. Although Seward now saw the wisdom in freeing Mason and Slidell, Lincoln remained opposed. Sumner presented letters from Bright and Cobden indicating that most of their people would fight if the president held onto the men and thereby condoned Wilkes's desecration of British honor. Even though Bright and Cobden had joined numerous church groups in England in urging arbitration, Palmerston and Russell vehemently rejected the prospect of another nation deciding their government's fate.60

The next day, Lincoln met for four hours with his cabinet, which, convinced of the danger of war and hearing no objection from the president, recommended the release of Mason and Slidell. Lincoln's unexpected silence mystified Seward. Just hours earlier the president had adamantly resisted their surrender. After the others had left the conference room, the secretary inquired about Lincoln's change of heart. The president smiled as he looked at Seward: “I found I could not make an argument that would satisfy my own mind, and that proved to me your ground was the right one.”61 The resolution of the problem was not that simple. Lincoln had doubtless intended to exploit the crisis for all it was worth—knowing that at the point of imminent conflict he could relent, safe in the knowledge that he had publicly opposed the surrender of Mason and Slidell but now having to comply with British demands because of the ongoing war with the Confederacy and the widespread belief that Wilkes had acted illegally.

Seward now bore the daunting responsibility of drafting a note to Lyons that camouflaged the submission to England. The captives were of “comparative unimportance” and would be “cheerfully liberated,” he wrote; Wilkes had violated international law in capturing them without also taking their papers and the Trent itself. Wilkes had acted correctly, though without authorization, in stopping a neutral ship carrying contraband. “All writers and judges pronounce naval or military persons in the service of the enemy contraband. Vattel says war allows us to cut off from an enemy all his resources, and to hinder him from sending ministers to solicit assistance. And Sir William Scott [Lord Stowell] says you may stop the ambassador of your enemy on his passage. Despatches are not less clearly contraband, and the bearers or couriers who undertake to carry them fall under the same condemnation.” Wilkes, however, had made a mistake in not seizing the Trent as a prize. The United States refused to grant an apology, but it would free Mason and Slidell and award reparations.62

Seward then made a bold argument for preserving the United States's honor. In the interests of neutral rights, the Americans were prepared “to do to the British nation just what we have always insisted all nations ought to do to us.” Seward insisted that he “was really defending and maintaining not an exclusively British interest but an old, honored and cherished American cause.” As Secretary of State James Madison declared in his 1804 instructions to his minister in England, James Monroe, “whenever property found in a neutral vessel is supposed to be liable on any ground to capture and condemnation, the rule in all cases is, that the question shall not be decided by the captor, but be carried before a legal tribunal.” Had Wilkes taken the vessel as a prize, he would have acted in accordance with freedom of the seas and international law.63

Adams in London had provided Seward with the rationale for releasing Mason and Slidell without a loss of face. The minister had stressed the importance of neutral rights and referred to Madison's instructions to Monroe in 1804. If the United States refused to comply with the British demand to free the captives, Adams asserted, it would “assume their old arrogant claim of the domination of the seas.” Furthermore, the surrender of the southern emissaries would soften the negative feelings of Europeans who had universally condemned their seizure as a violation of international law.64

Writer James Russell Lowell expressed popular sentiment in the United States in these lines from “Jonathan to John”:

It don't seem hardly right, John,

When both my hands was full,

To stump me to a fight, John,—

Your cousin tu, John Bull!

We give the critters back, John,

Cos Abram thought 'twas right;

It warn't your bullying clack, John,

Provokin' us to fight.65

The British had a mixed reaction to the Lincoln administration's decision to free the captives. News of their release reached London on January 8, 1862, setting off wild celebrations throughout the country; the justification did not. Even the Duke of Argyll set aside his ardent Union support to argue that the Trent's passage between neutral ports had not permitted Wilkes to seize Mason and Slidell as contraband. In accordance with the French position, a vessel moving between neutral ports by its very nature could not carry contraband and was immune from search and seizure. And, as the duke asserted to Sumner in the United States, mere communications from a belligerent to a neutral did not constitute contraband. The distinguished British barrister, William Henry Harcourt (Lewis's stepson-in-law), agreed with Argyll. Writing under the pseudonym “Historicus,” Harcourt declared in the Times that in matters affecting contraband, “the destination of the ship is everything.” By definition, he asserted, a neutral vessel bound for a neutral port could not carry contraband. The crown's legal officers agreed, as did the British cabinet. Russell cited Vattel, Wheaton, and other experts on international law in claiming that neither the southern emissaries nor their papers fitted the category of contraband. It was immaterial that Wilkes had failed to take the vessel to a prize court.66

Seward had skillfully saved the Union's honor by disguising the capitulation in a haze of legalities, but beneath the verbiage lay an arguable defense of Wilkes's conduct that in the heat of the moment escaped attention. In a statement that reflected the reality of war, Seward asserted a fundamental principle of natural law: “If the safety of this Union required the detention of the captured persons, it would be the right and duty of this Government to detain them.” Vattel, as shown earlier, argued for the right of national preservation as a basic principle of international law.67 Wilkes had made this argument, and so had Gurowski in the State Department and Twisleton in England. Is it not the inherent right of a nation to safeguard its security? Should people at war permit a neutral to engage in conduct that helps their avowed enemy? Does a neutral flag protect belligerents aboard, regardless of their purpose? Surely it guarantees the safety of ambassadors of goodwill, but Mason and Slidell were not on a mission of goodwill. They sought British and French recognition, which, if achieved, could have dealt a death blow to the Union.

Mason and Slidell's objective raises questions about the widespread condemnation of Wilkes's actions. Their status constituted an arguable exception to the views of those specialists in international law who defended the sanctity of ambassadors as well as neutral vessels passing from one neutral port to another. No one could hold that a ship carrying such passengers was subject to capture only if headed toward an enemy port. If military or naval personnel in service of the enemy were subject to seizure—as they were, according to international law—certainly Mason and Slidell were no less dangerous because they wore civilian garb. Their purpose was to convince the world's two leading neutral nations to recognize the Confederacy and thereby facilitate its efforts to destroy the Union. The British commander of the Trent sacrificed all claim to neutrality by knowingly transporting two emissaries of a people at war, resisting a U.S. naval boarding party's right of search, then permitting the concealment of their dispatches and later delivery to the three southern commissioners already in Europe. American legal theorist Henry Wheaton maintained that the ship's destination was not the key determinant. Rather, both he and Lord Stowell contended that a belligerent had the right to confiscate enemy dispatches for adjudication. Common sense, if not natural law, presents a strong case that Wilkes's behavior was an act of self-defense.68

Just as the American Civil War ushered in many features of total conflict that previewed twentieth-century warfare, so did this nineteenth-century war include a diplomatic front that was part of the wartime arsenal and thus subject to broadened definitions and guidelines. President Davis looked backward in condemning Wilkes's seizure of Mason and Slidell as an act of barbarism. President Lincoln could have looked forward in defending his captain's action as appropriate to what the Civil War would become—an all-out war that thrust the divided nation into modern warfare and hence justified any action considered necessary to survival.

But Lincoln faced another, overriding consideration: War with England over debatable legal principles was too high a price to pay for refusing to release the captives. He did not attempt to find a legal justification for Wilkes's actions, and the massive sense of relief afforded by the settlement outweighed further thought on the subject. Lyons was correct in asserting that the British threat of war had dictated a resolution of the crisis. Indeed, he felt confident from the outset that if the Americans came to believe that Mason and Slidell's surrender did not constitute a national humiliation, they would comply with British demands.69 Prince Albert's wise counsel had left the way open for Seward's note to accomplish these objectives. From the beginning of the American conflict, Seward thought his only leverage in blocking diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy was to threaten war with England; yet in the Trent affair at least, his aggressive strategy became exposed as empty rhetoric. Ironically, his repeated warnings of war with England over intervention had so embittered Anglo-American relations that they fueled the Trent crisis. The Lincoln administration had engaged in a dangerous game of provocation in attempting to ward off foreign intervention and had thereby intensified every issue between the Atlantic nations. Henry Adams perceptively remarked that Seward “shaves closer to the teeth of the lion than he ought.” Yet Seward chose peace and thereby helped to alleviate British concern about his motives. Russell did not regret the Trent crisis. “The unanimity shewn here, the vigorous dispatch of troops and ships—the loyal determination of Canada, may save us in a contest for a long while to come and in fact the cost incurred may be true economy.” But the chief redeeming feature was its showing that Seward's threats of war with England were “all buncom[be].”70

The Trent affair nonetheless demonstrated that British recognition of the Confederacy was a distinct possibility. Increasing numbers of observers believed southern independence a fait accompli and renounced the Union for refusing to accept reality. Others warned that the economic damage caused by the war and the Union blockade would hit England hard by the spring of 1862. A January 1862 survey revealed that the number of unemployed workers had jumped three times what they were in November and that those on short time had risen more than 50 percent.71 A large number of British citizens wondered about their government's responsibility to intervene in the name of civilization. Popular sentiment in England favored some sort of intervention designed to end a war that many observers once thought the Confederate army had resolved at Bull Run in July 1861.

French support for the British position also pointed to intervention in the American war. Before the Diplomatic Corps in Paris, the emperor told the large gathering that an Anglo-American war would hurt the United States but be “a calamity to Europe.” Dayton noted that pressure had grown on France's industrial interests and that its population was suffering, leading to the belief that removing the blockade would resolve all problems by providing cotton and a market. Despite Thouvenel's assurances, Dayton saw a real threat of France and England interfering with the blockade. The Paris government knew that the United States did not want a foreign war along with the domestic conflict, and reasonably assumed that it would “submit to much, rather than incur that hazard.” The meetings of the legislative chambers in London and Paris, particularly in considering questions about the blockade's effectiveness, would undoubtedly “renew the agitation” over recognizing the Confederacy and raising the blockade. Union seizure of the Confederacy's major seaports would discourage French or British challenges to the blockade that could lead to their recognizing the Confederacy in an effort to end the war in the interests of themselves “and the world.”72

Another point needs emphasis: British exultation over the captives' release did not signify favor for the Confederacy; rather, it was an expression of relief from having escaped war with the United States. Furthermore, the British came to realize that Seward's warnings of war were mere bluffs and felt justified in maintaining their neutrality. It appears certain that the breakdown of the Atlantic cable just before the crisis (fortuitous for the Union, not so for the Confederacy) had delayed each side's awareness of the other side's angry reaction and thereby provided a release time for emotions. The Times praised the preservation of honor but then assailed Mason and Slidell for doing “more than any other men to get up the insane prejudice against England which disgraces the morality and disorders the policy of the Union.” They deserved no accolades. “They are personally nothing to us. They must not suppose, because we have gone to the very verge of a great war to rescue them, that therefore they are precious in our eyes. We should have done just as much to rescue two of their own Negroes.”73

The Trent settlement strongly suggested that the Palmerston ministry intended to remain neutral. Indeed, the crisis forced the Atlantic nations to clarify the rights of neutrals and thereby reduced the likelihood of such problems arising again. Had the British wanted a pretext for challenging the Union blockade, they could have found it in these explosive events. But they did not, strongly signaling that their neutrality was genuine. In a tumultuous time when numerous voices called for recognizing the Confederacy, the Palmerston ministry won widespread acclaim at home for resolving the Trent matter short of war and thus gained greater leverage in determining foreign policy.

Palmerston's ability to maintain control augured well for the Union, even if not noticed in the Union at the time. The Confederacy, however, detected dangerous signs. One of its agents in England, Henry Hotze, warned that the crisis had hurt the southern cause by furnishing the British government with a diplomatic victory that it could use as evidence of wise leadership in resisting the popular pressure for intervention. Richmond editor E. A. Pollard later wrote that the peaceful settlement of the Trent affair had provided “a sharp check to the long cherished imagination of the interference of England in the war.” The elder Adams offered a similar assessment while remaining leery of England's imperial nature. The Palmerston ministry had gained a much stronger political position at home, making it critical for the Union to avoid any issue that provided the British with a reason to intervene. England, he told a friend, would continue to “sit as a cold spectator, ready to make the best of our calamity the moment there is a sufficient excuse to interfere.”74

But perhaps a clerk in the War Department in Richmond put his finger on the real importance of the Trent affair. The Confederacy, he believed, had lost all hope for an alliance with England. “Now we must depend upon our own strong arms.”75