CHAPTER 6

The Paradox of Intervention

At first the [Union] government was considered as unfaithful to humanity in not proclaiming emancipation, and when it appeared that slavery, by being thus forced into the contest, must suffer, and perhaps perish in the conflict, then the war had become an intolerable propagandism of emancipation by the sword.

—WILLIAM H. SEWARD, July 28, 1862

Any proposal to recognize the Southern Confederacy would irritate the United States, and any proposal to the Confederate States to return to the Union would irritate the Confederates.

—LORD JOHN RUSSELL, July 31, 1862

We shall prosecute this war to its end.

—WILLIAM H. SEWARD, September 8, 1862

Immediately after Lindsay's motion failed, rumors swirled around London that Baltimore had fallen to Confederate forces, edging England and France closer to a joint mediation that implied southern independence. Russell felt relieved about recent events on the battlefield, hoping the collapse of Washington's neighboring city would break the Union's resolve and lead it to the peace table. Southern separation, repeated many British observers, would benefit both antagonists. But the rumors from the battlefield proved unfounded, and, despite the swelling popular interest in mediation, the Palmerston government felt no inordinate pressure from mill workers and other constituents. Time had not yet become a factor, for most economic indicators suggested that the growing cotton shortage would not have a major impact on families until the spring of 1863. Russell noted, however, that the Union's stubborn refusal to accept its dissolution could still force British involvement in the war. Seward had done nothing “to prevent the cry that may arise here, from the obstinacy and passion of the North.” France likewise seemed poised to intervene. Slidell informed Mason that Napoleon appeared ready to step into the conflict, with or without England's involvement. In a highly questionable assertion, Mercier assured William Stuart in a conversation in Washington that most Americans would approve a joint mediation.1

By late July two of the most powerful figures in England, John Russell and William E. Gladstone, had agreed on joint mediation as the chief means for halting the war before it spread beyond American borders. The Lincoln administration, complained Stuart, was about to wage a war on slavery intended to incite disturbances throughout the southern plantations and pull Confederate soldiers home from battle to protect their families. Emancipation, confiscation of property in slaves, incorporation of freed blacks into the Union army—all these measures ensured widespread racial upheaval having both national and international repercussions. The British must somehow stop the conflagration. From Washington came the counterargument that, ironically, forecast the same devastating outcome if Britain interfered in the war. Seward had told Russell that intervention would cause a disaster. But the British foreign secretary misconstrued Seward's cautionary note to mean that to block intervention, the White House planned to instigate a slave uprising. Out of this would come a race war, Russell wrote Stuart in a note shared with Seward, that would “only make other nations more desirous to see an end of this desolating and destructive conflict.” Intervention or nonintervention—either avenue promised a calamity of international proportions if the war continued its widening path of mutual destruction.2

If proclaiming the war a crusade against slavery at the outset would have turned England against the Confederacy, that moment had passed. The expected shift in Lincoln's objective to antislavery infuriated most British contemporaries because, they charged, it rested on expediency rather than morality. In the initial fighting, the president had surprised the British by focusing on preserving the Union. Slavery was not the issue, he had argued; indeed, he had maintained his prepresidential policy (and that of the Republican Party) of renouncing any legal right to disturb the institution short of halting its expansion and thereby promoting its extinction over a period of time. Political considerations had weighed heavily on his mind. When the war erupted, Lincoln could not risk driving the Border States into the Confederate camp by calling for emancipation. He also knew that Americans were deeply divided over slavery. Many had quietly condoned bondage by refusing to oppose it. Some preferred compensated emancipation. Others rejected the abolitionists' call for racial equality. Finally, he and Seward had feared that emancipation would undermine reported Union sentiment in the South. None of these arguments had convinced British observers of the Union's need for caution in the early stages of the war. Now, in late July 1862, the Lincoln administration had incurred a severe setback at Richmond's gates and discovered there was no substantial Unionist sentiment in the South. The president, many British bitterly charged, had adopted emancipation in a desperate attempt to avert defeat by encouraging slave insurrections aimed at destroying the cotton kingdom from within. Only an intervention leading to southern separation could counter his hypocrisy.3

The mutual misperceptions continued as Seward furiously accused the British of supporting the “slaveholding insurgents.” How could the Palmerston ministry be so blind as to fall under the spell of traitors who wanted to overthrow the duly constituted U.S. government? How could it sympathize with a people who sought to protect slavery by posing as a friend to the British (and the French) while withholding cotton to force recognition? The Confederacy was waging a war against humanity that the British had prolonged by holding out the hope of intervention. A Union victory “does not satisfy our enemies abroad. Defeats in their eyes prove our national incapacity.” Even the White House call for emancipation had drawn little support. “At first the [Union] government was considered as unfaithful to humanity in not proclaiming emancipation, and when it appeared that slavery, by being thus forced into the contest, must suffer, and perhaps perish in the conflict, then the war had become an intolerable propagandism of emancipation by the sword.” British intervention, Seward darkly predicted, would escalate the American conflict into “a war of the world.”4

Their diametrically opposite stands on intervention permeated every issue between the Washington and London governments and threatened to cause a third Anglo-American war surely conducive to Confederate statehood. Each side dreaded an already horrific contest made worse by the certain outbreak of slave insurrections and the onset of a race conflict that crossed sectional and perhaps national boundaries. Intervention, the Lincoln administration warned, would intensify the fighting, extend the war, and pull in other nations. Failure to intervene, the Palmerston ministry feared, ensured the same results. Such was the paradox of intervention.

First reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, July 22, 1862. Francis B. Carpenter's painting presented to Congress in 1878. Cabinet members, left to right: Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, President Abraham Lincoln, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Interior Caleb B. Smith, Secretary of State William H. Seward, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, and Attorney General Edward Bates (out of picture). (Courtesy of the National Archives)

Lincoln had diplomatic, political, and military objectives in mind when in mid-July 1862 he decided on emancipation. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton had urged him to meet with New York Democrat Francis B. Cutting, a prominent attorney who had proposed a spotlight on antislavery as a means for winning the war. Two hours later, Lincoln emerged from their discussion convinced that emancipation would block recognition of the Confederacy while satisfying the Republican Party's antislavery proponents. The president also realized he had to take stronger measures in light of McClellan's inability to seize Richmond. At a meeting with his cabinet that same day, he declared his intention to support emancipation as a “necessary military measure.” According to his draft of the Emancipation Proclamation read to advisers, all slaves in states still in rebellion by January 1, 1863, would be free.5

All cabinet members but one supported the measure. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair felt that emancipation would undermine the Republican Party's control of Congress after the fall elections. The next day, however, he changed his position, conceding that emancipation might discourage outside intervention in the war. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase strongly endorsed Lincoln's proposal. A longtime advocate of abolition, Chase recommended that the president facilitate the new policy by directing his generals to arm the slaves. Stanton had made the same argument and now called for immediate emancipation. But Seward thought the timing was not right. He had never wanted “to proselyte with the sword” and now, in a perceptive prophecy of England's worst fears, warned that the British government would regard emancipation as an insidious effort to incite a slave uprising and thus feel compelled to intervene. Wait until the Union won another battle, he urged the president. Premature emancipation would appear to be “the last measure of an exhausted government, a cry for help … our last shriek, on the retreat.” Lincoln agreed to hold the Proclamation until the Union secured a decisive victory on the battlefield.6

Lincoln had become convinced that the exigencies of war demanded a forceful end to slavery. He considered himself patient and forgiving. “Still I must save this government if possible. What I cannot do, of course I will not do; but it may as well be understood, once for all, that I shall not surrender this game leaving any available card unplayed.” He reiterated his stand to Democrat August Belmont, a financial magnate from New York: “This government cannot much longer play a game in which it stakes all, and its enemies stake nothing. Those enemies must understand that they cannot experiment for ten years trying to destroy the government, and if they fail still come back into the Union unhurt.” Belmont concurred but cautioned that a dramatic pronouncement would provoke southerners. They had already accused the Union of seeking “conquest and subjugation” and thereby hurt its chances for ginning up support from within the Confederacy. A public stand against slavery must not take on a vengeful appearance that substantiated the Confederacy's arguments in Europe. Lincoln, however, had run out of patience—particularly with the Border States, whose slaveholders had hampered the war effort. He told a Union supporter in the South that by insisting that “the government shall not strike its open enemies, lest they be struck by accident,” the Border States had caused a “paralysis—the dead palsy—of the government in this whole struggle.” The time had come for action. “The truth is, that what is done, and omitted, about slaves, is done and omitted on … military necessity.”7

Lincoln decided on emancipation for several reasons, the most important being to facilitate victory in the war. He had first suggested colonization, then gradual emancipation with compensation, and, finally, confiscation, but the war's demands had pushed him further into the antislavery camp and now necessitated the revolutionary measure of emancipation. Success meant the death of the Old South. Had not Confederate vice president Alexander H. Stephens called slavery the cornerstone of southern civilization? Inherent in emancipation was the possibility of violence between slave and owner or of slave abandonment of the plantation, either of which would destroy the institution from within and bring down the Confederacy. Lincoln sought no slave rebellion, but he knew that emancipation in wartime had the potential for stirring up hatreds between blacks and whites that would not end even after all slaves were free. He had no choice. The Union's failure to administer a lethal blow on the battlefield forced him to change strategy.8

Lincoln's intention to preserve the Union had thus tied the Confederacy's defeat to slavery's death and the growing sense of higher purpose in the war. Continued setbacks on the battlefield had encouraged him to adopt a progressively harder stance against slavery that became vital to victory. To wrap his military objective in universal humanitarian principles would give added meaning to the war and perhaps raise Union morale. This was a risky proposition, he knew, for few northerners cared about emancipation except as it hurt the Confederacy. But the desire to win the war, he also knew, would override any reservations about considering antislavery a moral as well as a military good. Lincoln's intensely personal religion rested on the eternal laws of necessity, leading him to believe in a divine plan in which he as president acted as God's instrument in effecting great social change whose present priority was to end slavery in order to win the war. In his Inaugural Address of March 1861, he had called for a mystical and permanent Union that grew out of the natural rights undergirding the Declaration of Independence. Fulfillment of those principles dictated the abolition of slavery.9

The Civil War, Lincoln had come to believe, must beget a spiritual rebirth of the republic. As a master of rhetoric, he often used biblical imagery in focusing on the “born again” concept found in the New Testament Gospel of John. During the 1850s, Lincoln had set out a belief he adhered to throughout the ensuing conflict: “Our republican robe is soiled, and trailed in the dust,” he declared. “Let us repurify it. Let us turn and wash it white, in the spirit, if not the blood, of the Revolution.”10 Thus the same synergy that drove the great document of 1776 was now moving the American nation closer to the ultimate goal of freedom for all. The Declaration of Independence had provided the spirit of the Constitution, which itself served as the first real attempt to manifest that ideal, to be shaped by evolutionary development in accordance with the steady progression toward universal liberty. The end of slavery became morally inseparable from the sanctity of representative government through a vastly improved Union. By viewing the war for the Union as a moral crusade, the president attempted to vindicate the massive suffering as crucial to convincing Americans to accept profound social change; as the reward, he suggested, divine intervention would ensure victory. Lincoln's appeal to the universal principles of right and wrong led him to conclude that the destruction of the southern government and the southern way of life was necessary to creating a better republic.

In line with Lincoln's thinking, the Union and the Confederacy were engaged in an ideological conflict that, ironically, revolved around the ways each antagonist selectively interpreted the same two sacred documents: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. According to northern nationalists, the longevity of the Union proved its constitutional legitimacy to anyone seeking its dissolution. Southern states' rightists countered that their growing minority status had left them vulnerable to northern oppression and that the right to withdraw from the governing pact derived from a fundamental precept of the Declaration. Had not the contract theory of seventeenth-century English philosopher John Locke provided justification for the American colonies' break with Mother England in 1776? Yet southerners refused to address the natural rights principles of the Declaration and argued instead for the constitutionality of secession by charging the Washington government with interfering in their domestic concerns—especially their right to property in slaves as guaranteed by the due process clause in the Fifth Amendment of the Bill of Rights. Lincoln responded that the promises of freedom contained in the Declaration of Independence had gone unfulfilled in the Constitution and that his responsibility as president was to redeem those ideals by forming a more perfect Union.

Lincoln recognized that a central problem lay unresolved during the first eighty-five years of the Union's existence: the eternal struggle between human and property rights. The ideals of the Declaration of Independence, he believed, provided the moral and intellectual framework of the Civil War. Liberty in this self-professed republic was not yet available to all Americans; black people in the United States did not enjoy the natural rights guaranteed by the Declaration's underlying philosophy. Lincoln firmly believed that the present conflict rested primarily on Union-Confederate differences over slavery and thereby constituted an integral part of the larger problem of ensuring freedom to every American. The most profound complication in freeing enslaved blacks lay in the property rights protected by the Constitution. Lincoln thought that the human rights exalted in the Declaration of Independence took priority over all else and soon considered it his responsibility as president to kill slavery by using its protector—the Constitution—as its executioner. Only by constitutional amendment could the peculiar institution finally be destroyed.

Lincoln's calculated change in direction promised to escalate the war to another level of ferocity, for the Confederacy also claimed to be fighting against slavery—the enslavement by Union oppressors in violating its people's right to own slaves. “Sooner than submit to Northern Slavery, I prefer death,” wrote a South Carolina officer to his wife. Or as a Kentucky doctor and soldier put it, “We are fighting for our liberty, against tyrants of the North … who are determined to destroy slavery.” Freedom to own slaves was crucial, according to a Mississippi officer, for “without slavery little of our territory is worth a cent.” A Georgian insisted that southerners had the choice of being “either slaves in the Union or freemen out of it.” Just as fervently did southerners declare their support for freedom, a term they broadly conceived to include their right to own slaves.11

By mid-1862 Lincoln had decided to incorporate antislavery into his military effort to save the Union and, at the same time, drive home the point that a republic based on the Declaration of Independence could not coexist with a Constitution that safeguarded human bondage. Casting universal meaning onto such vicious fighting, he also knew, would justify the sacrifices and maintain unity, cause, and morale. Freedom and slavery could not live in harmony together—requiring the latter to become the chief casualty of the war. Union and freedom—the longtime objective of Daniel Webster, one of Lincoln's most revered figures in history—could at last become one.12

Lincoln was not alone in believing that emancipation offered both moral and military benefits to the Union. Those on both sides of the issue recognized that emancipation, even though a wartime measure, would culminate in the end of slavery and, by definition, topple the Old South as well. In a Sunday cabinet meeting in early August, Chase asserted that quashing the rebellion and killing slavery were inseparable. Seward likewise emphasized the importance of black freedom in eroding the Confederacy from within. Lincoln's conversion to emancipation as a wartime expedient became evident in his concession that he was “pretty well cured of objections to any measure except want of adaptedness to put down the rebellion.” From the Western Theater of the war came support for black liberation as a military instrument. General Ulysses S. Grant, who had made his mark in brutal, hammerlike victories at Forts Henry and Donelson, Shiloh, and Corinth, now hailed emancipation as essential to victory. An officer under his command affirmed that the best policy was “to be terrible on the enemy. I am using Negroes all the time for my work as teamsters, and have 1,000 employed.” Grant assured his family that his sole purpose was “to put down the rebellion…. I don't know what is to become of these poor people in the end, but it weakens the enemy to take them from them.”13

To Lincoln, the wisdom of the policy was indisputable as the danger of outside intervention became more pronounced. In mid-July, French writer Count Agénor-Etienne de Gasparin had sent him a note expressing astonishment at the Union's failures on the battlefield and claiming he had done everything to discourage European intervention. The Confederacy could not win without foreign assistance, Gasparin wrote. Only when the Lincoln administration shifted its wartime objective to abolition would the interventionists lose their fire. The president agreed that a cry for black freedom would reduce the threat of outside interference.14

Ideal and reality had meshed in shaping Lincoln's decision, combining his longtime animosity toward slavery with the Union's misfortunes on the battlefield to formulate a new policy that initially drew little support. Numerous white northerners actively opposed a war on behalf of black people, while others remained silent, feeling no moral responsibility to slaves. Abolitionists denounced any action short of freeing all slaves with no compensation, perceiving remuneration to slaveowners as a compromise with sin. Antislavery groups called for a moderate approach, warning that a radical solution would spawn more violence. Northern Democrats blasted the Republicans as fanatics who stirred up racial hatreds that guaranteed more antiblack riots similar to those in northern cities during that summer of 1862. Lincoln realized that many Union soldiers would refuse to fight a war against slavery, but he also knew that they wanted to win the war and that necessity had forced him into a limited form of emancipation. And yet, though he stipulated that only those slaves in states still in rebellion would go free, he knew that once the shackles of a few were broken, the cracks would run through the entire edifice.15

Lincoln could not have known at the time that Mason had failed to budge Russell from his stance of neutrality. Nor would the British foreign secretary meet with Mason. Russell (like Palmerston) did not believe the Confederacy had won independence. Foreign intervention must not determine the fate of recognition, he repeated in response to Mason's written appeals; the Confederacy must first establish its status as a nation. Russell clarified his government's dilemma: “Any proposal to recognize the Southern Confederacy would irritate the United States, and any proposal to the Confederate States to return to the Union would irritate the Confederates.” Mason refused to give up. The Confederacy had demonstrated “the capacity and the determination to maintain its independence,” obligating other governments to extend recognition. Then, adding to the confusion, he repeated his perplexing assertion first expressed in his February meeting with Russell (one similar to that made by Slidell to Napoleon): The Confederacy sought simple recognition—“no aid from, nor intervention by, foreign Powers.” Such a statement conveyed a dreamlike quality—that merely being “right” guaranteed victory. Other nations must understand, Mason held, that “for whatever purpose the war was begun, it was continued now only in a vindictive and unreasoning spirit.” Refusal to grant recognition ensured a longer war that hurt Europeans as well as Americans. Russell coldly repeated that only the war could shape British policy.16

More likely, differing interpretations of the struggle rather than ulterior motives dictated the British response to the war. Russell opposed recognition but strongly considered mediation if staying out of the war hurt his government's interests. To him, there were vast differences between the two interventionist measures being debated. Mediation aimed only to end the war, whereas recognition granted nationhood and made Britain the Confederacy's partner in the war. Secession was a constitutional issue that did not concern the British; whether the South had succeeded in withdrawing from the Union was of no consequence. The London ministry's chief objective was to stop the fighting before it spread beyond the United States. To the Lincoln administration, however, there was no distinction between mediation and recognition: Indeed, the first would lead to the second. Moreover, both measures constituted outside interference in American domestic affairs and hence violated national sovereignty. Russell regarded continued British neutrality to be the most feasible policy at this time. Southerners claimed to have won independence; northerners thought they were on the way to restoring the Union. This core issue still unresolved, Russell could take no action. “In the face of the fluctuating events of the war, the alternations of victory and defeat …; placed, too, between allegations so contradictory on the part of the contending Powers, Her Majesty's Government are still determined to wait.” Recognition, he wrote Mason, would come of “an independence achieved by victory, and maintained by a successful resistance to all attempts to overthrow it. That time, however, has not, in the judgment of Her Majesty's Government, yet arrived.”17

Mason remained embittered over the British refusal to grant recognition outright but optimistic that mediation could lead to the same end. Russell, Mason groused, had ignored every piece of evidence confirming the Confederacy's credibility as a nation and would extend recognition only after its military forces had won decisively on the battlefield—at precisely the point it no longer needed recognition. He might have added that in winning the war, the Confederacy would have achieved nationhood and thereby would be entitled to recognition without having to ask. What a needless expenditure of blood, he thought. An Anglo-French mediation, probably joined by Austria, Prussia, and Russia, seemed likely that summer. If so, the Union would come under great pressure to reconsider the feasibility of continuing the war. Intervention was nigh, Mason wrote his wife. He appeared correct, for Gladstone had moved deeper into that camp. “This bloody and purposeless conflict should cease,” the chancellor exclaimed to a friend. To his wife, he triumphantly wrote that Palmerston “has come exactly to my mind about some early representation of a friendly kind to America, if we can get France and Russia to join.”18

Although Russell had discouraged Mason by insisting on continued neutrality, the truth was that such a stand helped the Confederacy by offering the possibility of mediation. Short of force, the only avenue to ending the war lay in convincing the warring parties to negotiate a settlement. And that moment would come only after both sides had exhausted themselves in combat and welcomed mediation as an honorable way out. But even that scenario carried a result that the British had highlighted and the Union had vehemently rejected: southern separation. Perhaps with that thought in mind, the Union had no choice but to express confidence that it would win the war despite repeated reversals on the battlefield. Edmund Hammond cautioned the ministry to offer mediation only after the Union realized that subjugation was impossible. Lyons thought his government, as the representative of a civilized people, bore the responsibility to end the war and warned that coming cotton shortages would dictate an intervention.19 Whatever Russell's true motives, his pledge of neutrality created the appearance of unbending resistance to intervention when in reality it opened the way to mediation—an outcome Mason must have known encompassed southern separation because he had already welcomed mediation as a step toward recognition.

Further pressure for intervention had come from the ongoing controversy between the Union and the British ministry over the Confederacy's shipbuilding program in England. Adams had protested that this year-old business—allegedly engaged in the construction of warships for Italy or Spain—was a poorly disguised attempt to build a Confederate navy. Moreover, British refusal to stop such activities constituted a blatant breach of neutrality that favored the Confederacy. Russell said his government lacked the authority to act on Adams's complaints. The Foreign Enlistment Act of 1819, he explained, stipulated that for a violation to occur, the equipping and manning of war vessels must take place in British territory. The British admiralty would take action against the shipbuilding firms only if the United States proved that the construction teams had armed the ships in England and for the Confederacy. Adams, Russell insisted, had never amassed such evidence. The Union minister vehemently disagreed, suspecting that Russell had cited municipal law to defend a violation of British neutrality.20

The shipbuilding issue threatened to mesh with the recognition crisis in the summer of 1862, when the first ships rolled off the line that Confederate naval agent James D. Bulloch had contracted a year earlier with Laird Brothers of Liverpool—vessels that satisfied the letter but not the spirit of British law. Bulloch, a native of Georgia, had been assigned to Liverpool to fit out privateers and purchase war munitions. An uncle of the future president Theodore Roosevelt, he had served as a U.S. naval officer before becoming a merchant marine captain in New York City. When he arrived in England in June 1861, Bulloch's instructions were to arrange for the building of cruisers fast enough to raid Union commerce and to purchase blockade-runners to keep the Confederacy supplied. Within a year he had assumed responsibility for another project: the construction of two ironclad rams, equipped with iron piercers extending six or seven feet beyond the prow and beneath the water, to destroy the Union's wooden-hulled blockade vessels. In promoting these objectives, he secured financial backing from the Liverpool firm of Fraser, Trenholm and Company, and he did not hide in the shadows. Bulloch boarded his ships almost every day, inspecting their progress and visibly establishing himself as the person in control. The State Department in Washington had already alerted the acting consul in Liverpool, Henry Wilding, that Bulloch headed the Confederate Secret Service in England.21

Bulloch confronted all manner of obstacles—including Union spies along with a prying British press that printed every detail it uncovered about his operations. His chief antagonist as of late 1861 was the Union's new consul at Liverpool, Thomas Haines Dudley, a Quaker with strong antislavery sentiments who proved resourceful and persistent. On arriving, in November, at his post, which was a pro-Confederate hotspot, Dudley managed to hire a host of local detectives and Union supporters to gather information about two gunboats suspected of being under construction for the Confederacy and built for speed—the Oreto, by W. C. Miller and Sons and Messrs. Fawcett, Preston and Company, and the twin-engined No. 290, by Laird Brothers. But he was unable to counter Bulloch's skill in subterfuge. From the Birkenhead Ironworks on the Mersey River emerged in March 1862 the Oreto, ostensibly built for an Italian owner from Palermo but under a British captain and flag and destined for the Confederacy. The unarmed warship headed for Nassau in the British Bahamas, where Confederates fitted it with guns as a privateer and renamed it the CSSFlorida.22

More menacing was the construction of a larger ship fitted for cannon but innocuously referred to as No. 290 (called the Enrica at first launch in May 1862) because it was the 290th vessel built in the Lairds' Birkenhead shipyard. From two officers of the Confederate commerce raider CSSSumter, Dudley had testimony that No. 290 was for the Confederacy. Soon afterward, a number of reliable observers, including the foreman in the Lairds' shipyard, confirmed the allegation.23

Dudley asserted that No. 290 was a gunboat built to destroy Union commerce. It had magazines, powder canisters, and platforms attached to the decks for carrying swivel guns. It had a two-ton steam device that could lift the propeller from the water, a feature that enhanced speed by diminishing drag. And it could spend long periods at sea because its combined steam and sail power freed the vessel from the need for coal, and its condensing device cooled the water tanks and provided fresh water for the crew. Shipbuilders marveled at the sight, claiming that “no better vessel of her class was ever built.” Dudley agreed. “When completed and armed, she will be a most formidable and dangerous craft, and if not prevented from going to sea, will do much mischief to our commerce.”24

The Laird brothers, John and Henry, did not deny that No. 290 was a war vessel, but they said that it had been commissioned for the Spanish government. Dudley asked Adams to make inquiries at the Spanish embassy in London to confirm the claim. When the Spanish minister denied it, Dudley concluded that the ship was indeed for the Confederacy.25

The case against No. 290 seemed irrefutable—or so Dudley thought. The critical hole in his information was its lack of documented wrongdoing and his consequent dependence on hearsay. No matter how firm his belief, he had to prove that the builders had violated the Foreign Enlistment Act by “fitting out or equipping” the vessel for the Confederacy while in England. Dudley wanted to send a formal note to Liverpool's customs officials, asking them to seize the vessel. But Adams preferred to send the request to Russell through diplomatic channels. The minister then prematurely heated up the matter by including in his June 23 “formal remonstrance” Dudley's in-house note containing the charges. Concerned that the Confederacy was using England as a base of military operations against the Union, Adams insisted that the Palmerston ministry abide by its professed neutrality to stop this conduct. In an implicit reference to the Birkenhead firm's elder John Laird, who had founded the company and later became a member of Parliament, Adams accused the Confederacy of pursuing this project in “the dockyard of a person now sitting as a member of the House of Commons.”26

In this rife atmosphere, Adams's suspicions rose unjustifiably when he did not receive a prompt response to his complaint. The foreign secretary had sought counsel from his legal advisers, who caused further delay by turning for information to the customs surveyor at Liverpool, Edward Morgan. Under orders of the customs collector and reputed Confederate sympathizer Samuel Price Edwards, Morgan personally inspected the vessel on June 28 and concluded that Dudley had been correct in reporting that the vessel had powder canisters on board but no guns or gun carriages. The builders permitted access to the ship and did nothing “to disguise what is most apparent to all—that she is intended for a ship of war.” They did not deny that the vessel was under contract to a foreign power but refused to reveal its destination once completed.27

The case, according to customs officials, was not strong enough to justify government action. According to Felix Hamel, the solicitor for the Board of Customs Commissioners in London, the American claim did not contain sufficient grounds for intervening in the matter. Government officials should not take action “without the clearest evidence of a distinct violation of the Foreign Enlistment Act.” A wrongful seizure could have serious legal consequences.28

Despite these findings, the crown's law officers—Attorney General William Atherton and his associate, Solicitor General Roundell Palmer—recommended on June 30 that Russell examine the accusations contained in Adams's note. If Adams was correct, they declared to Russell, the action had violated the law and the ship must not leave the yard. Dudley's charges raised “grounds of reasonable suspicion” about the vessel that a shipyard foreman reinforced by declaring it bound for the Confederacy. If so, the law officers asserted, the ship “must be intended for some warlike purpose.” Liverpool officials should investigate whether the evidence was sufficient to invoke the Foreign Enlistment Act.29

Yet two days later, on July 1, Treasury officials agreed with Hamel's argument against government intervention and recommended that Dudley submit the evidence he had gathered if he wished to begin prosecution proceedings. The Treasury officials sent their thoughts to Edmund Hammond, permanent undersecretary at the Foreign Office, who forwarded them to Russell.30

For some unexplained reason, Russell ignored his law officers' advice to conduct an inquiry into Dudley's accusations and followed the more cautious approach advocated by his Treasury Department. On July 4 he asked Adams for Dudley's evidence, which three days later the minister agreed to send. Nothing in the record suggests that the foreign secretary acted out of an oft-alleged pro-Confederate sentiment; rather, he seems to have relied on his customs officials' belief that the evidence of wrongdoing appeared inconclusive and not worth the risk of a wrongful seizure. The onus for proving the case was Dudley's. Thus did the matter settle into a drawn-out process that inadvertently bought time for the builders of No. 290 to complete its construction.31

The London ministry quickly realized that Dudley's charges rested almost entirely on hearsay—largely because Bulloch had shrewdly refrained from arming or equipping No. 290 while it was in England and had therefore broken no law in contracting for and building the vessel. Dudley had collected accurate information on the ship's purpose but was unable to substantiate his suspicion of a Confederate connection. His so-called evidence included no names of informants and thus lacked “legally certified affidavits from firsthand witnesses.” He could not divulge his sources because they were Union supporters in a hotbed of Confederate sympathizers, and he suspected Edwards of being a Confederate agent. On July 9 Dudley told the Liverpool customs officials what he knew without identifying his informants.32

Two days later Hamel expanded on his views, leading Edwards to inform Dudley that the British government must not seize the vessel. Most of the evidence, “if not all,” Hamel insisted, was “hearsay and inadmissible.” In calling no witnesses to appear and providing no names, Dudley had failed to present any information “amounting to prima facie proof sufficient to justify a seizure, much less to support it in a court of law.” Hamel sent these observations to Treasury officials the next day, July 12.33

Dudley nonetheless persisted. Edwards reported that the consul and his recently hired British solicitor, A. T. Squarey, had appeared with witnesses and affidavits, asking him to seize the gunboat based on the allegation that Laird Brothers had fitted it out for the Confederacy. But Dudley's only piece of important evidence was that of William Passmore, who had signed on as a sailor on the vessel, and the only item placed on board was coal. Passmore had learned that Laird Brothers was constructing a war vessel and applied for duty to Captain Matthew Butcher on June 21. The captain explained that the ship was going to the Confederacy. Passmore had had fighting experience on a British warship during the Crimean War and, after asking to serve as signalman, was given a password to use when boarding in two days—the number 290. He could see that the ship was fitted for fighting: It had a magazine and shot and canister racks on deck, and it was pierced for guns with the sockets for the bolts already in place. It carried ample provisions, nearly three hundred tons of coal, and about thirty hands, most of whom had served on war vessels. Indeed, one of them had been on the Confederate steamship Sumter. All of the men understood that No. 290 was commissioned for Confederate service. Butcher was the sailing master and Bulloch the fighting captain. The vessel, to be known as the CSSAlabama, was to be used in the Confederacy's war against the Union.34

Two other testimonials affirmed that No. 290 was built for the Confederacy. Henry Wilding, now U.S. vice consul at Liverpool, and private detective Matthew Maguire of that city who also worked for Dudley, learned from an apprentice employed at the Laird yard, one Richard Brogan, that the firm had built the vessel to carry guns. Bulloch had selected the timber for the ship and had asked Brogan to serve as carpenter's mate for three years. The vessel would carry 120 men, about 30 of them already signed on—as Passmore had attested. The petty officers had agreed to a three-year service, the seamen to five months. Wilding and Maguire also confirmed Passmore's testimony given that same day—that all hands knew No. 290 to be a Confederate warship.35

To advise in preparing their case, Adams and Dudley had hired the queen's counsel, Robert P. Collier, who was a member of Parliament and one of England's acknowledged experts on admiralty and maritime law, and the Foreign Enlistment Act. After reviewing the documentation they had compiled, Collier completed his study and his findings reached Russell perhaps on July 23. The Americans' evidence, Collier wrote, was “almost conclusive” that the vessel “is being fitted out” for the Confederacy in violation of the Foreign Enlistment Act. The chief customs officer at Liverpool must “seize the vessel, with a view to her condemnation.” It would be difficult, Collier concluded, “to make out a stronger case of infringement of the Foreign Enlistment Act, which, if not enforced on this occasion, is little better than a dead letter.” Russell directed his undersecretary to send the case materials to the law officers. The British government, it appeared, was going to take action.36

But the Palmerston ministry did not issue a detention order, primarily because of an unforeseen event. The papers containing Collier's views had arrived in two batches at the home of the crown's chief law officer, Queen's Advocate Sir John Harding, the first on July 23 and the other three days later. But at this crucial moment Harding had a mental breakdown. Only his wife, Lady Harding, knew the state of her husband, but she was so distraught that she said nothing about his condition. Staying with friends, he had carried the papers with him.37

On the evening of July 28, Atherton retrieved the case materials from Harding and with Palmer studied them through the night and into the next morning before endorsing Collier's conclusions. Russell should detain No. 290 until a full-scale investigation could take place, the two law officers declared. The depositions presented by Dudley, “coupled with the character and structure” of the ship, made it “reasonably clear” that its destination was the Confederacy. Passmore's testimony made it impossible to deny that the vessel was a warship. A jury might decide against the seizure, largely because “neither guns nor ammunition have as yet been shipped” and the crew had not signed on as “a military crew.” But given the clear impression of wrongdoing, the owners had to prove innocence. Atherton and Palmer agreed with Collier that the government should not adhere to a strict interpretation of the terms “equip,” “furnish,” “fit out,” or “arm”—all found in the Foreign Enlistment Act. This narrow approach “would fritter away the act, and give impunity to open and flagrant violation of its provisions.” The lack of guns on board did not prove innocence. “The vessel, cargo, and stores may be properly condemned.”38

In the meantime, however, Bulloch managed No. 290's escape from Birkenhead—also on July 28—while it was taking on coal and provisions. Now known as the Enrica, it pulled away from the dock that evening, dropped anchor off Seacombe on the Mersey River, and left the next morning for a purported trial cruise. A large number of party-minded men and women were on deck, some of the men admitting they were part of the crew for the gunboat. But the vessel had aroused no suspicion, leaving port in the company of the steam tug HMSHercules. No beams were on board the gunboat, despite Dudley's claims. The master of the Hercules, Thomas Miller, attested to seeing no guns; in fact, he saw nothing except coal. Miller transported up to thirty men to the vessel to serve as either sailors or firemen, but he carried no guns, powder, or ammunition.39

When the tug's master returned, however, it became clear that Bulloch had perpetrated a massive hoax. Miller reported that the Enrica, which was cruising off Point Lynus, had six guns hidden below and was taking on powder from another ship. Too late Dudley demanded a stop to “this flagrant violation of neutrality,” for Bulloch had masterfully arranged its escape.40

Meanwhile, the foreign secretary was out of town and the law officers' urgent message did not reach him until early in the afternoon of July 29. Again for some unexplained reason, Russell did not send the detention order to Liverpool until late in the evening of July 31. Although Edwards had not found evidence to substantiate Dudley's allegation of guns on the Enrica, the Board of Customs Commissioners instructed Liverpool officials to detain the ship. By that time, the Enrica had been at sea for fifty-five hours. The delay caused by Harding's illness proved costly. If Atherton and Palmer had possessed the July 23 information on the twenty-fourth or even the twenty-fifth, they undoubtedly would have approved the detention at that time and blocked the ship's departure.41

The British had evidence that the Enrica had taken on cargo from the Bahama, a steamer that had arrived in Liverpool the previous evening out of Angra, the capital of Terceira Island in the Azores, after its clearance from Liverpool for Nassau. To inquiries about the cargo, the master said he had taken on sixteen cases of unidentified goods, presumably arms, and transferred them to a Spanish vessel before returning to Liverpool with a supply of coal. Off the Western Islands, he saw the Enrica, well armed and with a 100-pounder pivot gun mounted on the stern that he thought capable of destroying seaport towns along the north Atlantic coast. The master of the Bahama had transferred nineteen cases of goods to the Enrica, and Captain Raphael Semmes, former commander of the Confederate steamer Sumter, had arrived on the Bahama, along with about fifty others, to become captain and crew of the gunboat, now called the Alabama.42

Bulloch had taken the Alabama from British waters to a spot near the northwest coast of Ireland. He had then returned to Liverpool to arrange the transportation of Captain Semmes and his officers, along with the battery and ordnance stores, men's clothing and other supplies, and 250 tons of coal. The two vessels met at Praya, on Terceira Island. Captain Semmes and his officers arrived from Nassau around August 8 and five days later joined Bulloch on the Bahama, bound for the Alabama. They reached Praya on August 20 and boarded the cruiser; good weather allowed them to finish the exchange on the late morning of August 22. After mounting the last gun and stowing other ammunition, they completed the coaling process by ten the following night. On Sunday morning, August 25, the Alabama and the Bahama steamed out into Portuguese waters and, with the crews of both vessels giving three cheers, raised Confederate colors on the new cruiser. By midnight, the officers had made all the arrangements for the men on the Alabama, and Captain Semmes prepared to cross the Atlantic. Bulloch climbed off the vessel, noting that he felt like he was leaving his home.43

Dudley and Adams had mishandled the process by failing to understand all the legal steps involved in detaining a vessel. This was all the more inexcusable in light of their experiences in trying to stop the Florida's departure. Dudley had been watching No. 290 since his arrival in Liverpool months earlier. His detectives had kept him fully apprised of the ship's character. Thus, along with Bulloch's expert maneuvering, poor preparation was primarily responsible for the Alabama's escape, not British collusion or purposeful delay. Dudley and Adams did not start gathering evidence for a detention until July 16 and forwarded their findings to British customs officials on July 21–23. Adams had thought—erroneously—that his mere request for detention would suffice and had not taken into account the intricacies of the British legal system.44

Union officials had mistakenly accused the Palmerston ministry of hiding behind legal technicalities to implement a pro-Confederate policy. Seward sharply dismissed Stuart's claim that his government had been unable to act without evidence of wrongdoing. Dudley asserted that because of the Alabama's escape, “we are in more danger of intervention than we have been at any previous period…. They are all against us and would rejoice at our downfall.” Seward had in hand a letter written to a British colleague by the undersecretary of state for foreign affairs, Sir Austen Henry Layard, who criticized London's policies. The ministry's slowness to act had exposed it to accusations of violating neutrality.45 Only when the Confederacy met defeat at Gettysburg and Vicksburg the following July 1863 did it appear that the Union might win the war and that Russell could seize the war vessels and stifle the shipbuilding program.

Another outcome of the Union's battlefield victories was increased pressure on the British Foreign Office by Adams and Dudley to detain the two Laird rams. “If these ships go,” Moran confided to his diary, “nothing will prevent a war between the two countries.” Russell assured Adams that his protest had gone to the proper authorities in an effort to determine how to legally carry out the seizure. But Hamel found Dudley's evidence again insufficient to justify the action and warned that failure to win the case in court would result in “serious consequences in the shape of damages and costs.” After a lengthy delay caused by the annual vacation in August, Russell penned a note on September 1 declaring that his government would not seize the rams. On reading Russell's note two days later, Adams predicted that “a collision must now come of it.” In an uncharacteristic loss of control, he wrote Russell on September 5: “It would be superfluous in me to point out to your Lordship that this is war.” Adams's nerves had frayed so badly that he lashed out in a manner setting aside all diplomatic tact and apparently conceding the probability of war. He was not threatening war; rather, he was warning that the issue was moving in that direction and wanted to emphasize the danger. Nevertheless, he had made a poor choice of words.46

And all so unnecessary, for on the day before Adams's note arrived, September 4, Russell decided on his own volition to detain the rams for further investigation. The foreign secretary directed Layard to hold the rams “as soon as there is reason to believe that they are actually about to put out to sea, and to detain them until further orders.” Russell intended to test the Foreign Enlistment Act, knowing that British policy strongly suggested that ships with iron plates, rotating turrets (capable of housing guns and crew), and rams were warships and that the government had to assure Americans that it would not follow a policy of “neutral hostility.” Palmerston agreed with the decision, admitting that the government might ultimately have to free the rams because of the necessity of proving that they were for Confederate use against the Union. Although Adams complained that this action was not strong enough, Russell responded that with the Alabama, his government could not “admit assertions for proof, nor conjecture for certainty.” At long last, however, the Royal Navy provided a solution: It purchased the two rams in May 1864 and commissioned them as war vessels.47

Would the rams have made a difference in the war? Pure speculation, of course, but an accident in which one of the two former Confederate rams ran into another British vessel and did not draw its attention casts serious doubt on whether they had the capacity to raise the blockade and open southern ports. Yet the widespread perception of these ironclads disabling the wooden Union vessels and wreaking havoc along the Atlantic coast threatened to diminish the reality. The Union's consul general in Paris, John Bigelow, later asserted that the rams “would not only have opened every Confederate port to the commerce of the world, but they might have laid every important city on our seaboard under contribution.”48

By the time the rams' crisis subsided, the Alabama had sunk a Union warship and either burned or bonded more than sixty Union merchant vessels (including a large number of whaling ships that carried the oil necessary to keep Union machinery running), but it went to the bottom after an hour-long battle with the Union gunboat USSKearsarge off Cherbourg, France, while spectators watched on shore and in yachts. More so than the Laird rams, the Alabama's destructive activities created deep animosities toward the British that lingered for years after the war. Not until 1871 did the Treaty of Washington resolve the Alabama claims controversy with England by an arbitration settlement reached the following year that awarded the United States $15.5 million in damages. Russell later admitted that he should have ordered the ship's seizure while waiting for the law officers' report. “In a single instance, that of the escape of the ‘Alabama,'” he lamented, “we fell into error.”49

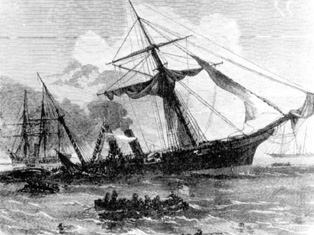

CSSAlabama sunk by USSKearsarge off Cherbourg, France, in the English Channel on June 19, 1864 (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Seward had considered the danger of intervention so serious by the summer of 1862 that he threatened to break off diplomatic relations with the British if they got involved in the war. In a section of a dispatch to Adams in London so explosive that it did not appear in the executive documents sent to Congress, the secretary declared that if Russell offered to “dictate, or to mediate or to advise or even to solicit or persuade,” the U.S. minister was to respond that he was “forbidden to debate, to hear or in any way receive, entertain, or transmit any communication of the kind.” Whether the British acted alone or with other nations in extending recognition to the Confederacy, Adams was to “immediately suspend” his functions as minister. If they followed recognition with “any act or declaration of War against the United States,” he was to sever diplomatic relations and return home. “You will perceive,” Seward gravely concluded, “that we have approached the contemplation of that crisis with the caution which great reluctance has inspired.”50

Seward's concerns were justified, for Gladstone had urged the ministry to support mediation. The chancellor of the exchequer not only cited economic and humanitarian reasons, but he also wished to halt a chain of events that would drag in other nations hurt by the war and culminate in their own clash over its spoils. In his diary, he recorded numerous attempts to devise a formula for peace. An unnamed “Southern Gentleman” highlighted the problems in drawing a border between the “Northern and Southern Republics.” Gladstone praised a best-selling pamphlet entitled The American Union, now in its fourth edition, in which Liverpool businessman James Spence rejected slavery as a cause of the war. Having served as a financial agent for the Confederacy, Spence seemed to have intimate knowledge of the situation as he argued for southern recognition. According to one biographer, Gladstone's primary motivations in life were religion and morality, which helped to guide his humanitarian concerns regarding the American war. Spence's interest rested on more practical considerations. He wanted to establish a steamship line between England and a southern port and a railroad from the Confederacy to Matamoros, Mexico, both permitting an evasion of the Union blockade that would translate into huge profits. Regardless of motives, the two men were strong voices for intervention.51

Gladstone sought only to end the war, though he had little grasp of its causes. After an early August cabinet meeting, he walked out with “a bad conscience” because his colleagues would not support recognition until both American antagonists agreed to it. This was an immoral stance, Gladstone wrote the Duke of Argyll. To permit the war to render its own verdict would extend the fighting and place the burden of guilt for the ensuing destruction on the European powers. England should join France and Russia in offering mediation—“Something, I trust, will be done before the hot weather is over to stop these frightful horrors.” Recalling his feelings some three decades after these events, Gladstone still maintained that he had regarded intervention as “an act of friendliness to all America.”52

Like numerous British contemporaries, the London press failed to comprehend the tenacity behind the issues between Union and Confederacy when advocating intervention as a humane gesture to end a war that the Union had brought on but that neither American antagonist understood. The Times termed the Union an “insensate and degenerate people” then pursuing a “hateful and atrocious war.” No one in Europe supported “this horrible war.” The Union, according to the Morning Post, had made many mistakes in waging this conflict. “Blinded by self-conceit, influenced by passion, reckless of the lessons of history, and deaf of warnings which everyone else could hear and tremble at, the people of the North plunged into hostilities with their fellow-citizens without so much as a definite idea what they were fighting for, or on what condition they would cease fighting.” Not realizing that the two sides fought so viciously because they so well understood what was at stake, the Morning Post accused the Union of going to war “without a cause,” “without a plan,” and “without a principle.” The fighting had swelled into a “suicidal frenzy” characterized by a “ferocity unknown since the times when Indian scalped Indian on the same continent.”53

The Lincoln administration had reason to worry about British and French intervention during the autumn of 1862. Palmerston informed the queen that October presented the most opportune time of the year for an armistice. The approach of winter would force a pause in the fighting, allowing each side to reflect on the wisdom of accepting outside mediation in a pointless war. Russell concurred with Palmerston's assessment. “Mercier's notion that we should make some move in October agrees very well with yours.” The queen did not object to an October intervention, although she preferred prior consultation with Austria, Prussia, and Russia. According to Adams some years afterward, King Leopold of Belgium (Victoria's uncle) had the greatest influence on her, and he urged Napoleon to convince England that it was in the interests of the European powers to end the American war, whether to recognize the Confederacy or, in the former Union minister's words, “take any other course likely to put an end to the American struggle.” In the hands of Napoleon, this was an invitation to use force.54

The growing fear of a slave uprising instigated by the Union had pushed England closer to an intervention. The Border States might abandon the Union in light of their dissatisfaction with Lincoln's call for emancipation. McClellan's rebuff at Richmond had shaken the Union's confidence. In arranging a mediation, Russell reminded Palmerston, its sponsors must have a peace program in hand. “I quite agree with you that a proposal for an armistice should be the first step; but we must be prepared to answer the question on what basis are we to negotiate?” If they had no satisfactory terms and the Union's leaders decided to resume the war, “it will be of little use to ask them to leave off.” At that point, he remarked with studied vagueness, the intervening powers might have to engage in some stronger action. An October cabinet meeting seemed advisable.55

The British stood on the verge of intervention primarily because the three most powerful figures in the government—Palmerston, Russell, and Gladstone—spoke favorably of mediation. Earl Granville was no proponent of intervention, but he admitted to great difficulty in halting a movement that had the support of his three esteemed colleagues. On an earlier occasion and on a different issue, he had remarked that Palmerston, Russell, and Gladstone constituted “a formidable phalanx when they are united in opposition to the whole Cabinet in foreign matters.” Most cabinet members supported mediation, Granville thought, but he considered it “decidedly premature” and “a great mistake.”56

The ministry encountered mixed interest in Parliament on suggesting a joint mediation. In early August, Russell notified the legislators that the ministry had the idea under consideration and that, if pursued, it intended to invite Russia's participation because of its well-known pro-Union sentiment. Argyll also supported the Union but opposed any British involvement until its leaders showed “some symptoms of doubt and irresolution.” Otherwise, he agreed with Russell that premature involvement could grow into “armed interference.” Mediation had a chance to work only if both antagonists accepted the offer. Argyll doubted that the Union could win the war, though he knew it did not share this belief. John Bright was confused. “I don't quite understand Lord Russell's American Declarations [in Parliament] last night,” he wrote Cobden. Either Charles P. Villiers or Thomas Milner-Gibson from the cabinet had assured him that Russell was “quite Northern in feeling and wishes.” If so, Bright cynically observed, the foreign secretary appeared “very unwilling to let anybody discover this from his official sayings.” But this lack of clarity did not matter. Russia, Bright declared, would not participate in a mediation without the Union's prior approval. Furthermore, slavery as an issue of morality lay behind the American contest, and humanity might profit from a longer war if it led to the death of that southern institution. Cobden concluded that his earlier argument made to Adams still held true: A mediation sponsored by all European powers was the “safest form of intervention.”57

At this point, it did not appear that Seward's belligerent strategy could block intervention. On the surface an outside involvement seemed unlikely. Parliament was prorogued on August 7, just two days after Russell expressed the ministry's interest in mediation, and the queen in her speech appeared to lean toward noninvolvement. Yet in the quiet recesses of the political stage, the Palmerston ministry had begun exploring other nations' sentiments for mediation. Russell and fellow proponents of intervention had naively dismissed the Union's opposition to all forms of intervention and continued to distinguish between mediation and recognition. To the Union, mediation was interchangeable with recognition in that both forms of intervention implied the existence of two entities. And that the Union could not accept.

Russia had become the key to a mediation, even though its opposition to intervention was well known in British and French governing circles. Russian ties with the Union ran deep and not only because Washington had made its good offices available in the Crimean War. The St. Petersburg government welcomed Lincoln's emancipation pronouncement as similar in spirit to Tsar Alexander's decision to free the serfs in March 1861. Moreover, the tsar had other considerations. He opposed rebellions against the established order, recognized that his country's primarily agricultural economy had incurred no hardships from the American war, and considered the Union a friend that had helped to balance off his Anglo-French rivals in the post–Crimean War era. In addition, the Russian minister to the United States, Baron Edouard de Stoeckl, had lived in Washington for two decades and was married to an American woman. He blamed irresponsible demagogues for bringing on the war and argued that the Union would staunchly oppose recognition of the Confederacy. And, according to Stuart, Stoeckl was confident that the Lincoln administration would turn down any interventionist offer. Yet the Russian minister feared that the Union was nearing exhaustion and would not risk a war with intervening powers over a mediation proposal. But, he added ominously, to push anything other than mediation carried a high risk; no people were more unpredictable than the Americans. The British chargé remained oblivious to the danger, insisting that recognition of the Confederacy would gain British “respectability” in the Union. “Peace might thus be accelerated.”58

In a twist of logic the British never understood, the Union's repeated failures on the battlefield paradoxically fueled its determination to defeat the Confederacy. The Times had pronounced McClellan's retreat from Richmond as proof of military weakness. In the Foreign Office, Hammond praised the South for waging a well-orchestrated war and noted its forward thinking in building a navy based on rams and ironclads. Stuart hailed the Union's losses in combat as necessary to persuade its leaders that mediation presented the only option to certain defeat. Secretary for War Lewis had a word of caution, however. The Lincoln administration might denounce mediation as an outside threat and exploit that fear to win more recruits. Seward had vehemently attacked intervention in any form as potentially “fatal to the United States.” Indeed, he had authorized Adams to warn England that if it intervened, he would suspend diplomatic relations. In the U.S. embassy in London, Moran recorded in his diary that the situation had become so tense that he had “placed the dispatch [containing these instructions] under lock and key for security's sake.”59

Edouard de Stoeckl, Russian minister to the United States (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The perception of certain intervention confirmed the White House's determination to stand behind emancipation as a military and diplomatic instrument that, the president knew, had profound postwar implications. Lincoln explained his broadly based stand on slavery in a published letter written in response to Horace Greeley's late August editorial in the New York Tribune supporting black liberation, addressed to the president as “The Prayer of Twenty Millions.” “My paramount object in this struggle,” Lincoln declared, “is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery…. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.” Realistic considerations had shaped his position. Emancipation had become a major means to win the war but not its chief objective.60

The Lincoln administration's opposition to slavery infuriated British observers because it did not rest on moral considerations. Stuart noted the assessment of Senator Charles Sumner, staunch abolitionist and chair of the Foreign Relations Committee. Most members of the president's cabinet, according to Sumner, supported emancipation as a way to salvage political control at home while preventing foreign intervention in the war. In a letter to Argyll, Sumner emphasized that the administration had united behind a battle for emancipation whose outcome depended on victory in the war. Argyll realized that the Union would never approve mediation and that compromise was impossible in a “Life or Death” struggle.61

But it was one thing to convince a pro-Unionist such as Argyll; it was another to ease the widespread indignation aroused by Lincoln's new policy of emancipation. Most Europeans complained that the Union had acted out of desperation and that the war itself, not the president's hollow claim to opposing slavery, would determine the question of intervention. Thus the mixed signals coming from the battlefield continued to stymie the proponents of intervention. Neither the British nor the French would act until the war's outcome had become clear. Stuart told Russell that only “another Bull Run” would increase the chances for peace. Although Hammond opposed the Union and thought its plight hopeless, he recommended against mediation until both sides had suffered extensive damage. Perhaps, he thought, a prolonged struggle would benefit his country's interests. The more destruction suffered by North and South, “the less likely will they be to court a quarrel with us or to prove formidable antagonists if they do so.” In France, Slidell's confidence in imminent recognition had wavered. Thouvenel had cooled Napoleon's ardor for acting independently of England and pointedly advised Slidell not to ask for recognition. When the southern minister sought to take advantage of recent Union setbacks in Richmond by seeking an interview with the emperor at Vichy, he was denied an audience. The Palmerston ministry would not act until both American antagonists were so spent that they welcomed mediation, and Napoleon refused to move without a British initiative.62

Not everyone in England wanted to shelve intervention until the war had run its course. Both Cobden and Argyll wrote Senator Sumner, expressing concern about the debilitating impact of imminent cotton shortages on mill families in Lancashire. Bright, on the other hand, supported the present policy of neutrality, arguing that the workers would not feel the brunt of the American war for at least another year. The Palmerston ministry and the news media, he charged, “had done all they can, short of direct interference by force of arms, to sustain the hopes of the Southern conspirators” who had tried to force England “to spill her blood and treasure in [their] Godless cause!” Gladstone admitted that the time was not yet right for mediation, but the European powers must not “stand silent without limit of time and witness these horrors and absurdities, which will soon have consumed more men, and done ten times more mischief than the Crimean War.” The extended conflict in the Crimea had been justified because of an unclear verdict on the battlefield. But no one could defend the fighting in America, for the outcome was “certain in the opinion of the whole world except one of the parties.” Mediation, Gladstone insisted, was the proper course in light of the “frightful misery which this civil conflict has brought upon other countries, and because of the unanimity with which it is condemned by the civilized world.”63

British textile workers had remained silent primarily because they had not yet experienced extreme economic hardships from the American war. Although the booming economy had declined initially, England's shipping and industrial production had continued to grow throughout the conflict. True, about three of every four mill workers were unemployed or on short time, and, reported Henry Adams, the misery in Lancashire (as well as in France) had spread at a disturbing rate. Both Gladstone and Lyons feared that mounting unrest would force the ministry to intervene. But these dire assessments were not accurate. Cotton continued to flow into England—from the American South, delivered by vessels that had run the Union blockade, from southern cotton confiscated by Union forces, and from expanded purchases in Brazil, China, Egypt, and India. Hotze further disheartened Benjamin by concluding that British workers had not banded with the Confederacy because public and private charities had alleviated much of the suffering and numerous mills had resumed production if only on a part-time basis.64

A further ameliorating factor was the evidence suggesting that British workers based their sentiments toward the war on the importance of freedom as well as on their economic welfare. Lincoln's reference to “a People's Contest” had confirmed the growing conviction that the Union supported liberty while the Confederacy fought for slavery. Had not the president told Congress that the Union advocated equal opportunity for all people, regardless of color or class? Karl Marx, the outspoken proponent of the working class, called on workers everywhere to rejoice over the path-breaking events in America. Lincoln led a “world-transforming … revolutionary movement” against the “slave oligarchy,” declared Marx from his place of exile in England. “As the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American anti-slavery war will do for the working classes.” Thus did domestic reform agendas help to determine the workers' reaction to the war and doubtless contribute to the shaping of government policies. Hotze also recognized the importance of slavery. The Lancashire workers, he reported to Richmond, were the only “class [that] continues actively inimical to us …. With them the unreasoning … aversion to our institutions is as firmly rooted as in any part of New England…. They look upon us, and … upon slavery as the author and source of their present miseries.”65

France's economic situation, however, had become more serious than England's and resulted in great pressure on the Napoleonic regime to intervene in America. Shipping and industrial production, though remaining fairly solvent, showed signs of imminent problems. By the spring of 1862, at a social function in Paris, Thouvenel uncharacteristically exclaimed to the Union minister in Brussels, Henry Sanford: “We are nearly out of cotton, and cotton we must have.” More telling, the French foreign minister elaborated on these feelings that same evening by assuring Sanford that “we are going to have cotton even if we are compelled to do something ourselves to obtain it.” Mercier likewise revealed a propensity to act. A mediation decision should await the outcome of the November congressional elections in America, he observed to Stuart. If the peace party made a strong showing, the European powers should offer joint mediation with “the greatest courtesy” as a prelude to recognition. So confident was he of this result that he recommended that the intervening powers' representatives in the United States carry a “Manifesto” authorizing them to grant recognition of the Confederacy on the spot when they thought the time appropriate. Stuart questioned the procedure but not the objective. Only the home governments involved in mediation should decide when to extend recognition, he asserted, not their spokesmen thousands of miles away. Furthermore, the intervening nations should skip mediation and immediately grant recognition. Mercier opposed this move, maintaining that it would provoke the Union while “playing away one of our best cards without doing us any good.”66

Both the French and the British had openly adopted the position that the Lincoln administration most feared: Mediation, they had finally announced, constituted the first step toward recognition. Mercier urged his superiors in Paris to work out a mediation program with the London ministry. A joint offer, the French minister said, might stiffen the resolve of the Peace Democrats. If the White House turned down the hand of friendship, the intervening powers must recognize the Confederacy. Russia's involvement in the plan would probably ensure Union compliance, but this arrangement was not vital in view of the Republican Party's expected defeat in the upcoming elections combined with the army's continued failures on the battlefield. Stuart had softened his stand, now supporting Mercier in a mediation and thinking that Russia would privately urge the Union to accept the offer while publicly opposing southern separation. If England did not join the French program, Stuart warned Russell, it would appear to have “some ulterior object in continuing to look quietly on.”67

Argyll continued to resist intervention, arguing that slavery was the primary issue and that only the war should decide the outcome. His stand was not surprising, given that his mother-in-law, the Duchess of Sutherland, had long fought slavery. Those who defined the issue as southern independence versus northern empire were wrong, Argyll wrote Gladstone. At stake was “one great cause, in respect to which both parties have been deeply guilty, but in respect to which, on the whole, the revolt of the South represents all that is bad, and wrong.” Slavery was “rotting the very heart and conscience of the Whites—all over the Union—in direct proportion to their complicity with it.” Only intense fighting could sear this great evil from America. England, Argyll insisted, must not permit its textile mills to become dependent again on southern cotton. Once the war had resolved these moral issues, “then I sh[oul]d not object to help in the terms of peace.”68

Arguments on both sides of the intervention issue drummed on, but the Palmerston ministry had clearly maintained its interest in mediation. More than a few British observers urged the prime minister to reconsider the impact of ending the flow of southern cotton. Would it not be better to turn to alternative sources of supply rather than continue to depend on the Confederacy? China, Egypt, India, Morocco, and Turkey—all of these countries were potential sources of cotton that, British investors assured the Foreign Office, could be developed. Stuart informed the ministry that southern armies were about to invade the Union and thereby convince its people that the time had come to make peace. Bright, however, noted that his own contacts in New York predicted a Union victory. Gladstone leaned toward Stuart's assessment and suggested to Argyll that the ministry propose recognition rather than mediation. “It is our absolute duty to recognise, when it has become sufficiently plain to mankind in general that Southern independence is established, i.e. that the South cannot be conquered.” Intervention would constitute “an act of charity.” Ignore White House threats about switching to a war against slavery. In a statement that again demonstrated Gladstone's failure to understand the enormity of the issues confronting the Union, he said that the intervening powers would only make matters worse if they warned the administration against “resorting in [its] extremity to a proclamation of Emancipation[,] for that I cannot think Lincoln would do.”69