CHAPTER 8

Union-Confederate Crisis over Intervention

[Union refusal of an armistice would provide] good reason for recognition and perhaps for more active intervention.

—NAPOLEON III, October 28, 1862

Can nothing be done to stop this dreadful war?

—ALEXANDER GORCHAKOV, October 29, 1862

Was there ever any war so horrible?

—LORD JOHN RUSSELL, November 1, 1862

This destructive and hopeless war [has to end].

—WILLIAM E. GLADSTONE, November 27, 1862

If there is a worse place than Hell, I am in it.

—ABRAHAM LINCOLN, December 16, 1862

European interest in intervention remained very much alive by the autumn of 1862. From their vantage point thousands of miles away, the British, French, Russians, Belgians, and others on the Continent had become increasingly concerned about the American struggle, hoping to see an end to the fighting before it endangered onlooking nations and required direct intervention. The American battlefield, it seemed clear after Antietam, would not determine a winner; rather, it promised endless carnage as both antagonists stubbornly fought on, each side resolved to grind out an ultimate victory that rested on virtual annihilation of the other's forces. The dictates of civilization and the principles of international law condoned an intervention when an ongoing war threatened the belligerents' neighbors. But the Union viscerally rejected any form of outside involvement as a challenge to its integrity and pledged war on the intruders. Furthermore, to step in at this point in the stalemated fighting would be tantamount to extending recognition to the Confederacy, allying with a slaveholding people, and deciding the war's outcome. The entire matter was ridden with complexities that baffled the strategists and political leaders, along with the learned philosophers and scholars, the hardline veteran warriors, the commercial magnates, the concerned civilians, and the workforce now beginning to suffer on a broad scale in the Old World's manufacturing districts.

Russell's waning hopes for intervention jumped dramatically in late October 1862, when Napoleon III took the lead in proposing a joint mediation based on an armistice. This was not his first attempt to sell this idea; he had suggested it to Slidell a few months earlier and had received a favorable reception. The emperor's ongoing problems with Italy had eased, allowing him to focus on domestic economic issues and to assuage a swelling national sentiment for southerners as victims of northern aggression. Russell welcomed the offer, although fully aware of the risks attached to working with the imperious leader.1

Further encouragement came from Washington, where Stuart reported both Russian and French interest. Stoeckl had conceded that intervention might become “useful” if the Peace Democrats won the congressional elections in November. Mercier felt optimistic about securing a peace after talking with leaders of both political parties in New York. Democrats in the state favored a mediation that did not stipulate a gradual end to slavery. Stuart thought Mercier “rather too anxious to precipitate matters” but held high hopes for Democrat Horatio Seymour in New York's gubernatorial contest, confident that such a high-profile victory would intensify the movement toward mediation. A special emissary from Europe should come to America to extend recognition as the way to end the war. “If independence has ever been nobly fought for and deserved,” Stuart sighed, “it has been so in the case of the Confederacy.” Mercier concurred but expressed concern about anti-British sentiment in the United States. Stoeckl, the French minister warned, might suggest a Franco-Russian mediation that ostensibly aimed to relieve this ill feeling but also drove a wedge between England and France. For that reason, Mercier insisted that all three powers make the proposal.2

Stuart had inaccurately gauged the Russian position. In late October 1862, Bayard Taylor, famous traveler and lecturer and secretary to Union minister Simon Cameron in St. Petersburg, met with Gorchakov and found him anxious to see the war end. The Russian foreign minister assured his country's friendship but thought “the chances of preserving the Union were growing more and more desperate.” He then asked in exasperation, “Can nothing be done to stop this dreadful war?” The Union had “few friends among the Powers. England rejoices over what is happening to you: she longs and prays for your overthrow.” France “is not your friend. Russia, alone, has stood by you from the first, and will continue to stand by you.” The other powers will propose intervention, but “we believe that intervention could do no good at present. Proposals will be made to Russia, to join in some plan of interference. She will refuse any invitation of the kind. Russia will occupy the same ground, as at the beginning of the struggle. You may rely upon it, she will not change. But we entreat you to settle the difficulty. I cannot express to you how profound an anxiety we feel—how serious are our fears.” Gorchakov emphasized that Russia would participate in the peace process only after both Union and Confederacy agreed to negotiate.3

Thus the republic remained in peril—from the outside as well as from within because now, with the slavery issue on the way to resolution, the French interventionists could act for economic and imperial reasons without alienating anyone over moral questions. Nonetheless, the new French foreign minister, Edouard Drouyn de Lhuys, assured Dayton that “France had no intention of intruding into American affairs,” either alone or with another nation. The emperor sought only to convey “the expression of a wish to be useful if it could be done with the assent of both parties.” His chief concern was the growing slaughter of the war. If Drouyn told the truth, and Dayton believed in the sincerity of his assurances, there remained Napoleon's mercurial behavior. Nothing was certain without his specific approval, and that appears “to have no fixed purpose but grows out of circumstances.”4 No matter how fervently denied, the strongest proponent of intervention in the fall of 1862 was France—or, more specifically, Napoleon. For the first time in the American war, he could support the Confederacy without fearing domestic repercussions over slavery.

Ironically, the prospect of French intervention endangered both the Union and the Confederacy, rising and falling in intensity throughout this tumultuous period in proportion to Napoleon's imperial designs and the capacity of his advisers to restrain him. The emperor considered recognition of the Confederacy as not only a means for securing cotton but also for satisfying his expansionist aims in Mexico. The Union minister to Belgium, Henry Sanford, repeatedly warned Seward of Napoleon's expansionist intentions in the Americas. Nor did Confederates lose sight of the reality that Napoleon would support them only if the act promoted his objectives. Mann in Belgium cautioned Secretary Benjamin about Napoleon's treachery: “I shall be agreeably disappointed if we do not in after years find France a more disagreeable neighbor on our southern border than the United States.” Benjamin was aware of its interest in Texas; French consular officials in Texas and Virginia had bluntly asked about reacquiring territories that Mexico had lost in its recent war with the United States. Indeed, the inquiries were not spontaneous because both consuls had used the same words in questioning the wisdom of Texas's staying in the Confederacy.5

Mercier's recommendation for immediate action led Napoleon to notify the Palmerston ministry of his interest in a tripartite intervention aimed at bringing the war to a close. Despite his rebuff by Russia just months earlier, the emperor led the British to think that the collaboration of a third party remained a distinct possibility. He met with Lord Cowley on October 27 to suggest an Anglo-French-Russian mediation offer that included an armistice and a suspension of the Union blockade, both for six months. This two-pronged approach, he told the British ambassador in Paris, would “give time for the present excitement to calm down” and for peace talks to begin. Russian participation was imperative. Drouyn later assured Cowley that the emperor's only objective was to end the war. Drouyn preferred waiting a while, thinking the Confederacy would amass more victories in the field. If the Union rejected the proposal, he warned, Russia would probably refuse to join England and France in extending recognition to the Confederacy. Napoleon, however, preferred to act now—but for reasons not confided to his advisers.6

The following day, October 28, Napoleon met with Slidell and revealed more ambitious intentions than those shared with Cowley. Less than three months earlier, he had declined a meeting with Slidell, largely because of his preoccupation with European affairs and his desire for the British to take the lead in any interventionist move. What had changed? On the surface, the emperor had become impatient with British hesitation and therefore pushed for Russian involvement. Furthermore, Italy was less on his mind, giving him more time to work with other nations in resolving the American question. But he had also seen an opportunity to acquire territory in North America—even if at southern expense. Although expressing support for the Confederacy, he noted his perplexity in demonstrating how to make his feelings known. Slidell believed that Napoleon did not wish to act alone. England, the emperor doubtless feared, would not join him in a mediation, wanting instead to “embroil with the United States” and thereby hurt French commerce. Russia was the key. “What do you think,” asked Napoleon, “of the joint mediation of France, England, and Russia? Would it, if proposed, be accepted by the two parties?”7

At first the emperor's proposal did not strike Slidell as any more hopeful than his previous ideas. Had they not discussed an Anglo-French undertaking the previous summer, raising Confederate hopes only again to see them dashed? The Union, he thought, would approve if Russia were involved, although he was uncertain of his own government's reaction. Russia would probably support the Union, but England's participation remained doubtful. Just that day Slidell had learned from a reliable source close to Palmerston that most members of his ministry opposed recognition at this time and that, despite Gladstone's public declarations about Confederate nationhood, nothing had changed. The Confederacy, Slidell stressed to Napoleon, could not favor a three-power mediation. In such an arrangement, “France could be outvoted.” Slidell had an alternative suggestion. A joint Anglo-French mediation might be acceptable if accompanied by “certain assurances” to the Confederacy—namely, recognition. Indeed, southerners welcomed his “umpirage.”8

Understanding the importance of winning Confederate support, Napoleon sweetened the offer. “My own preference,” he asserted, “is for a proposition of an armistice of six months, with the Southern ports open to the commerce of the world. This would put a stop to the effusion of blood, and hostilities would probably never be resumed. We can urge it on the high grounds of humanity and the interests of the whole civilized world.” But Slidell knew that the assurance of reopened trade to France did not go far enough; he had gotten nowhere on bringing this identical proposal to Thouvenel nearly nine months earlier. At this point, however, Thouvenel was no longer in office, and the emperor added a provision having profound ramifications. Union refusal of an armistice, he said, would provide “good reason for recognition and perhaps for more active intervention [emphasis added].”9

Napoleon's allusion to force was unmistakable. Slidell could barely contain himself as he pushed the emperor to guarantee action. “Such a course,” the Confederate minister responded, “would be judicious and acceptable.” But, he warned, Palmerston would probably reject any plan pointing to recognition. Neither Slidell nor the emperor, of course, could have known how close this proposal approached present thinking within London's leadership. They were unaware of the pressure growing for a mediation that everyone knew would lead to recognition. Nor could they have known that Russell, too, had intimated a resort to strong measures if either American belligerent refused mediation. Perhaps also unknown to Slidell, Napoleon was not concerned about whether England would oppose an intervention pointing to recognition, for he had not told Cowley of any further recourse if the Union rejected an armistice offer.10

Napoleon nevertheless hoped for British participation, even if the intervention entailed the possibility of military action. As a further assurance, he told Slidell of a letter in his possession from King Leopold of Belgium dated October 15 and written while Queen Victoria (his niece) was in Brussels, which contained a recommendation that one could interpret as an approval of force. The king first appealed to humanity in urging France, England, and Russia to end the war as a means for securing cotton for depressed mill workers across the Continent. The Union should concede southern independence, making it incumbent on the European powers to extend recognition. If the Union refused to do so, Leopold said that the intervening powers should adopt “any other course” necessary to end the war. Slidell was elated. “It is universally believed,” he wrote Benjamin, that “King Leopold's counsels have more influence with Queen Victoria than those of any other living man.”11

To determine the emperor's sincerity, Slidell asserted that Cowley and others in British governing circles claimed that the French had not expressed interest in intervention. Indeed, Slidell had recently informed Benjamin of Cowley's claim that his government had received no official notification of the French emperor's views on recognition, despite his oft-expressed sympathy for the Confederacy. Thouvenel had been surprised by Cowley's assertion, insisting that the French had consistently made clear that leadership must come from England and that his government's sole intention was to secure an armistice as the initial step toward peace. Slidell suspected that either the London government did not keep Cowley informed or he had purposely twisted the situation.12

The emperor smiled at Cowley's contention, remarking how the canons of diplomacy dictated that nothing existed unless it appeared in a formal note. Thouvenel, Napoleon stated, had doubtless spoken with Cowley about the matter and perhaps had not pressed it far enough. This response satisfied Slidell, who had long suspected that the former foreign minister had not acted strongly on the Italian issue as well, perhaps helping to explain why the emperor had removed him from office.13

Napoleon offered further support for the Confederacy by proposing that its emissaries contract for the construction of a navy in France. With a minimal number of ships, the Confederacy could inflict serious damage to Union commerce, and with only three or four steamers it could open some of its ports. Slidell jumped at the opportunity. “If the Emperor would give only some kind of verbal assurance that his police would not observe too closely when we wished to put on board guns and men we would gladly avail ourselves of it.”14

Napoleon cagily replied with a question: “Why could you not have them built as for the Italian Government? I do not think it would be difficult, but will consult the minister of marine about it.” The possibility of force now combined with the emperor's invitation to deception in surreptitiously building a Confederate navy. Certainly Napoleon's suggestion of force combined with his invitation to deception could not do much more to demonstrate his support for the Confederacy. Confederate officers in Mexico had expressed concern over the presence of so many French troops and ships—that more were there than required and that Napoleon had “ulterior views.” But, as earlier, Slidell dismissed the long-range costs of entering into such a pact and focused on the immediate need.15

Whatever thoughts Slidell tossed around in his mind, he regarded this moment as an opportunity to repeat his request for recognition. At Vichy the previous July, he reminded the emperor, he had sought a closer relationship between the Confederacy and France; now, to further entice him, Slidell asserted that his government in Richmond would not object to French reoccupation of Santo Domingo. Napoleon appeared receptive, mentioning a letter from a New Yorker attesting that many leading Democrats believed that recognition would help end the war. Slidell affirmed the writer's reliability; he had already seen the letter, which the British Parliament had sent to Lindsay and shown to Lord John Russell before sharing it with Michel Chevalier, a writer and economist who had great influence with the emperor.16

As if to justify his proposal for intervention, Napoleon turned his attention to the growing bloodshed in the American war. He praised Jeb Stuart's cavalry for its recent thrust into Pennsylvania and asked Slidell to trace its route on the map. As the Confederate minister enthusiastically did so, the emperor expressed amazement at Stuart's audacity along with the magnitude of Union casualties. Were the numbers exaggerated? Slidell said that the figures were much larger than released and that the Lincoln administration had intentionally kept them lower to maintain morale. “Why, this is a frightful carnage,” Napoleon declared with astonishment—worse than at Magenta in the recent war with Austria. “But,” Slidell commented, with a less-thansubtle nudge toward intervention, “Solferino and Magenta produced decisive results, while with us successive victories do not appear to bring us any nearer to a termination of the war.” When the rivers in the West were again navigable, he added, the war's atrocities would increase. French involvement would save numerous lives and earn the world's appreciation.17

An hour had passed, and the emperor brought the meeting to a close. Slidell, ever watchful for favorable signs, reported that Napoleon shook his hand, a European custom that further demonstrated his warm feeling for the Confederacy.18 But the reality ran counter to the perception. Napoleon had masterfully played to Slidell's emotions, winning his confidence and laying the basis for a Franco-Confederate friendship that, not by coincidence, promoted the emperor's Grand Design for the Americas.

Napoleon's interventionist proposal drew an exuberant reaction in the Confederate capital, tempered only by James Mason's recent reminder that any French move still depended on British participation. Slidell nonetheless remained optimistic. Sources from within the emperor's inner circle had privately assured him that the Paris government would not interfere with Confederate shipbuilding in France; they had already encouraged Bulloch in England to cross the channel and begin the process. This news did not surprise Benjamin. Before Slidell's note on the meeting arrived in Richmond, Mason had reported Napoleon's interest in an “ulterior action which would probably follow the offer of mediation.” The emperor had made the identical proposal—that the British and Russians join him in offering the American antagonists a six-month armistice accompanied by a lifted blockade for the same period. Reports were that Russia had agreed to it and, if so, Mason felt certain that England would likewise concur. Benjamin was so jubilant that he entered into a long discourse with Mason on the postwar problems facing the victorious Confederacy. Suspending the blockade, the secretary asserted, would ease the most pressing economic issues. Mason, however, cautioned that Napoleon's views had “lost their value to us, as his purpose not to act independently seems unaltered.” Benjamin nonetheless remained optimistic.19

Napoleon's proposal had raised the Confederacy's hopes while deepening its anger with England for refusing to take the initiative. Russell's support for intervention had remained within the ministry, unknown to southern leaders who continued to berate England over its rigid opposition to recognition. Before Napoleon had revealed his intentions, Benjamin complained to Mason about London's “unfriendly” treatment of the Confederacy. Russell had first ignored the Declaration of Paris in acquiescing to a paper blockade, then had committed a “rude incivility” in rejecting the minister's request for a meeting. Most exasperating, the British foreign secretary used Seward's words to warn that British intervention would cause a slave uprising. This charge was “derogatory to the government and without foundation in fact.” Russell had no “well-founded reason” for refusing to grant recognition. But southerners felt confident that change was coming. They believed, however erroneously, that there was considerable popular support in England for recognition and that Russell and his colleagues would soon be out of office because they had ignored this sentiment. Benjamin instructed Mason to lodge a protest against the British refusal to challenge the blockade and thereby give Russell time to reconsider the wisdom of denying recognition. Napoleon's proposal, doubtless by design, thus widened the impasse between Richmond and London while drawing France and the Confederacy closer together.20

Confederate leaders were unaware of Russell's support for the French proposal. Admittedly, he was not sanguine about its success, but he considered any measure worthwhile if it offered the slightest chance of stopping the war. To Lyons, the foreign secretary bitingly remarked that Napoleon expected both American antagonists to accept his plan, “the one on the ground of Union, and the other on the ground of separation!” Nothing suggested that either side was willing to lay down its arms. But the endless nature of this atrocious war justified the effort. Even the pro-Union Cobden had bitterly declared that “to preach peace” to northerners was “like speaking to mad dogs.” Most appalling, Lyons reported, was Seward's cold assertion that only the Confederacy's “extermination” would bring peace. Despite these obstacles, Russell insisted that the war's growing bloodshed necessitated any peace attempt, no matter how futile it seemed. Russell complained to Cowley that the Lincoln administration sought to “wear out the South by mutual slaughter. Was there ever any war so horrible?”21

Russell's desperate search for peace had led him deeper into a world of illusion. Not only did Napoleon's proposal offer scant hope for Union acceptance, but its implied resort to force escalated the potential for widening the American war to include all three prospective intervening powers along with other nations. Furthermore, a joint mediation built on an armistice confirmed the existence of two belligerents and had already proved unacceptable to the Lincoln administration. Moreover, the Union could never agree to a six-month suspension of the blockade, which guaranteed a Confederate buildup.22 How would Napoleon react to the Union's certain rejection of his plan? Was not the use of force more than a possibility? Russell was aware of Washington's continued adamant resistance to any form of intervention, and he had witnessed the emperor's perfidy in the recent Anglo-French-Spanish debt-collecting venture in Mexico. Had not Napoleon devised an imperialist scheme that England and Spain had felt compelled to abandon? The cabinet, Russell knew, would strenuously object to the emperor's new enterprise, regardless of its alleged humanitarian base. A peace-seeking project in the American war would facilitate the Napoleonic family's long-sought return to North America and thereby tip the world balance of power in France's favor. Yet more significant to Russell was that if a prolonged war endangered the economic stability of other countries, international law justified an intervention to stop the fighting. Russia might join that pristine effort, particularly if France were involved to ease St. Petersburg's concern over both England's acquisitive nature and the Union's distrust of the Palmerston ministry. If the powers could persuade Union and Confederacy to enter into peace talks, the pressure from Peace Democrats and other antiwar groups might mesh with the certainty of continued mutual destruction to dictate an end to the hostilities.

Thus Russell thought the French proposal worth pursuing. He admitted to Palmerston that there was “little chance of our good offices being accepted in America,” but, he added, “we should make them such as would be creditable to us in Europe.” Those nations joining Napoleon's plan “ought to require both parties to consent to examine, first, whether there are any terms upon which North and South would consent to restore the Union; and secondly, failing any such terms, whether there are any terms upon which both would consent to separate.” Russell did not explain how the intervening powers would “require” the two sides to consider peace terms, nor did he posit any response to a rejection of terms by one or both warring parties. But a resort to force seemed likely in either case. And, of course, he could not assume Russian involvement, which both England and France considered indispensable. This was only a “rough sketch” of the project, Russell acknowledged in a clear instance of faith without works. But he intended to flesh out the details at the cabinet meeting. It would be an “honourable proposal,” although he raised more doubt about its efficacy by concluding that “the North and probably the South will refuse it.”23

Palmerston remained wary, still believing mediation a sound if premature approach. He had asked the Belgian king whether “the time had come to offer a mediation and to recognize the Southern States.” To turn down Napoleon's overture, Leopold replied, would help those in France who supported the Union as a postwar obstacle to England's imperialist ambitions. Palmerston weighed the alternatives, then directed Russell to delay any action until the cabinet discussed the “French Scheme.” The prime minister did not trust Napoleon, and he doubted that the Union would accept the proposal. The Lincoln administration knew that if the Confederacy opened its cotton stores to European buyers, it would “contrive somehow or other to get the value back in muskets and warlike Stores.” Furthermore, Palmerston repeated, the intervening powers had no solution to the slavery problem. The French, he cynically remarked, could pose as disinterested peacemakers because they were not bound by the “Shackles of Principle and of Right and Wrong on these Matters, as on all others than we are.” The ministry must wait for the Union's congressional elections.24

Continued hesitation seemed wise in light of Stuart's prediction that the Peace Democrats would win in a landslide and support mediation. He and Mercier agreed that Seymour's expected victory in the New York governor's race would ensure an intervention aimed at ending the war. Stoeckl concurred, thinking “the time may be very near.” One good sign, the Russian minister observed, lay in a recent conversation with Seward in which the secretary of state no longer threatened military retaliation against nations extending recognition. The time had arrived, insisted Stuart. “We might now recognize the South without much risk to ourselves.”25

But Stuart was wrong in his assurance of an overwhelming Democratic success in the November elections. So excited was he over the early returns that he prematurely notified his home office of a major victory and proclaimed that the time had come for intervention. Elated by the news, Russell told his colleague in the cabinet, Sir George Grey, that the new Democratic leaders would doubtless block the resurgence of war in the spring. “I heartily wish them success.” But later reports all but crushed Russell's hopes. The Republicans had not fared badly in the elections. Granted, the Democrats had gained thirty-four congressional seats and had won the gubernatorial contests in New York and New Jersey. They had also secured control of the legislatures in Illinois, Indiana, and New Jersey. But the Republicans had held on to all but two of the nineteen free state governors' houses and all but three of the same nineteen legislatures. In the Senate, the Republicans gained five seats, and in the House they maintained a twenty-five–vote lead. Furthermore, in six of the states controlled by Democrats, their lead was precariously narrow. As these truths slowly sank in, Stuart's enthusiasm for intervention slipped away—along with Russell's excitement.26

In truth, political chaos reigned in the Union. It was driven to a fever pitch first by Lincoln's long-anticipated decision to relieve George McClellan (a Democratic stalwart) of command of the Army of the Potomac following his refusal to pursue Lee into Virginia after the battle of Antietam, and second by the Democrats' public statements of interest in foreign mediation. Many observers regarded the president's personnel action as a victory for the war effort. Did he not seek a warrior rather than a priest? McClellan's supporters demanded revenge for what they charged was a purely political move. Lyons arrived back in Washington just as Democrats boisterously proclaimed their intention to handcuff the president and throw him in jail. Some party members advocated an armistice, followed by a special convention to change the Constitution in ways that would convince southerners “to return to the Union.” Lyons, however, noted the private opinions of numerous other Democrats who sought an armistice as a “preliminary to peace—and for the sake of peace would be willing to let the Cotton States at least depart.”27

If most Democratic Party spokesmen leaned toward southern separation, Lyons observed, they could not say so publicly. Instead, they called for a more aggressive war effort to embarrass the White House, gain a stronger position on the battlefield before accepting an armistice, and secure more territory in the event of a separation. Mediation would be acceptable to the Democrats if they could establish control over the present administration and if the offer came from “all the Powers of Europe”—which Lyons interpreted as “principally Russia in addition to England and France, and perhaps ‘Prussia.'” But he was not optimistic. The Democrats were uneasy about inviting other nations to help determine American affairs, and southerners did not have a “shadow of a desire to return to the Union.” For the moment, “foreign intervention, short of the use of force, could only make matters worse here.”28

Meanwhile, Slidell had become more hopeful about France's intervention in the war. He reported that three agents from the French banking house of Émile Erlanger and Company were en route to Richmond with a loan proposal. Two days after his October 28 meeting with Napoleon, Slidell noted, Mercier received instructions to make clear to the Lincoln administration that the emperor considered southern independence a fait accompli and that continuation of the war would hurt all civilized countries. On November 2, before the election returns in the United States, the French government sent a circular note to all European heads of state except those in England and Russia, inviting them to appeal to both Union and Confederacy to accept an armistice accompanied by a raised Union blockade. To England and Russia went special invitations to join the proposal; Slidell believed that the emperor had earlier received Russia's concurrence. The British, Slidell thought, would join either with France and Russia or with France and other governments, but not with France alone. Spain, Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, and others would undoubtedly support the proposal. Although uncertain about Austria, he thought it would probably be more supportive than Russia. Slidell was not concerned. Even if England and Russia declined the overture, “I now believe that France will act without them.”29

Mercier, in fact, urged his government to act alone and, ignoring Drouyn's October 30 assurance against force, to threaten military measures in attempting to persuade the Union to accept intervention. Like Stuart, Mercier had declared a Democratic victory in the congressional elections and thought the party “timid” for not seeking mediation. France must secure the Palmerston ministry's public approval of a unilateral approach that would imply Europe's acceptance of the move. The drawback of Russia's involvement, he warned, was that its friendship with the Union would remove “the element of intimidation, which though kept in the background, must be felt by the United States to exist.” Admittedly, participation in a joint mediation effort by all the continental powers “might have the effect of reconciling the pride of the United States to negotiation with the South.” But, Mercier said, the program might have a greater chance if Russia were not a party and the use of force remained a viable option to ending the war. The Lincoln administration would find it difficult to reject a mediation led by France alone (or with England). It knew that both nations would resort to naval power to protect their “obvious and pressing interest” in stopping the war.30

Lyons acknowledged that the implied use of force must lay behind any successful intervention but, contrary to Mercier, found that factor a major reason for opposing the move. While he was in London, several cabinet members told Lyons that they resisted interfering in the war but feared that growing popular pressure might force them to approve that step. The Democrats did not control the U.S. government, he wrote Russell, and Lincoln's recent removal of McClellan from command had forged unusual ties between moderates and radicals within the Republican Party who believed that reconciliation with the South was not possible until the Union “ruined and subjugated if not exterminated” the Confederacy. Democrats warned that Lincoln would drum up more support for the war by denouncing mediation as a violation of his nation's sovereignty—particularly if the British were involved. Recognition by itself, Lyons insisted, was of no value to the Confederacy. “I do not clearly understand what advantage is expected to result from a simple recognition of the Southern Government.” Nor could he envision the Great Powers “breaking up the blockade by force of arms, or engaging in hostilities with the United States in support of the independence of the South.” They also had no terms conducive to a compromise settlement. “All hope of the re-construction of the Union appears to be fading away, even from the minds of those who most ardently desire it.”31

Lyons argued that British involvement would undermine any mediation effort. The Americans were so suspicious of the London ministry that they would reject a proposal even if the Russians participated in its formulation. Then, “if nothing followed, we should have played out a good card without making a trick.” A unilateral French intervention would have a greater chance for acceptance by the Union than one that included the British, and a multilateral intervention might work as long as the British were not involved. “The bitter portion of the draft which the Americans would have to swallow in a case of joint mediation would be the English portion, and the more it is diluted by the mixture of foreign elements the better.” Mercier knew, as did all Europeans, that a resumption of the fighting in the spring of 1863 would further diminish the cotton crop and heavily damage the textile industries across the Continent. Intervention was necessary, he insisted, even if France acted alone and the effort benefited the Confederacy by challenging the blockade. The Union must realize that its rejection of mediation would lead to “something more in favour of the South than naked recognition.” Russian participation, Lyons argued, was “essential” to winning Union compliance, but Stoeckl had already made clear that his government would not follow “in the wake of the French and English governments.” Lyons conceded that Mercier was correct in believing that some intimidation was vital and that the blockade was the “critical point.” The Union understood that reopening southern ports would “give up the war forever,” whereas the Confederacy recognized that an armistice without a lifted blockade was meaningless. For these reasons, Lyons reasoned, if England and France threatened force and failed to follow through, they would be “crying out Wolf now, when there is no Wolf.”32

Napoleon's proposal had introduced the reality of a wider war to the intervention controversy. Russell was not taken aback. He had earlier supported an armistice that most likely would have led to recognition and possible conflict; he now leaned toward the emperor's plan, which sharply increased the likelihood of forceful actions after the extension of recognition. The foreign secretary had learned from the Mexican experience that Napoleon was capable of any action needed to satisfy his imperial interests. Why would the emperor act with restraint when both his reputation and a French toehold on the North American continent were at stake? Russell, however, considered the French proposal the final opportunity to end the American war and refused to let that moment pass.

Secretary Lewis strongly opposed the French program as a catalyst for war. In early November he circulated a lengthy memorandum among his cabinet colleagues citing the dangers of intervention and denying that the Confederacy deserved recognition. His 15,000-word paper, entitled “Recognition of the Independence of the Southern States of the North American Union,” was a collaborative work with his stepson-in-law, William Vernon Harcourt, who later became the first scholar to hold the Whewell Chair of International Law at Cambridge University. In London, the Spectator identified Harcourt as coauthor of the essay and lauded his use of history and international law to undermine the rationale for intervention.33

Under the pseudonym “Historicus,” Harcourt also wrote a string of letters opposing intervention that appeared in the Times. His central theme, “The International Doctrine of Recognition,” contained the same arguments found in Lewis's memorandum. According to Historicus, “Rebellion, until it has succeeded, is Treason”; “when it is successful, it becomes independence. And thus the only real test of independence is final success.” A joint mediation “would practically place our honour in the hands of our copartners in the intervention.” This business was not “child's play.” A European intervention did not guarantee peace. “To interpose without the means or the intention to carry into effect a permanent pacification is not to intervene, but to intermeddle.” Although the step might be “wise,” “right,” and “necessary,” it could not be “short, simple, or peaceable.” Past experience showed that intervention “almost inevitably … results in war.” The intervening powers could not succeed “except by recourse to arms; it may be by making war upon the North, it may be by making war upon the South, or, what is still more probable, it may be by making war upon both in turns.” To argue that an armistice could end an “irrepressible conflict” was “childish in the extreme.” The Great Powers lived in a “Paradise of Fools” if they intervened in the American war with neither peace terms nor a readiness to use force. “We are asked to go we know not whither, in order to do we know not what.” England must maintain neutrality.34

Lewis meanwhile assured his colleagues that Russell was correct in saying that the American war had threatened neutral nations. The fighting had stalemated, with the blockade inflicting “greater loss, privation, and suffering to England and France, than was ever produced to neutral nations by a war.” Many British observers believed that southern separation would eliminate the blockade and reopen the cotton flow to their textile mills. The war's atrocities had led numerous British citizens to the “rational and laudable desire” for their government to intervene and stop the conflict. But, Lewis noted, intervention between “two angry belligerents, at the moment of their greatest exasperation, [was] playing with edge tools.” With the outcome of the war not yet decided, intervention would promote the southern cause and result in war with the Union.35

The decisive point in the recognition controversy was whether the Confederacy had established its independence. “A state whose independence is recognized by a third state is as independent without that recognition as with it.” It was “the acknowledgment of a fact.” No nation had the right to grant recognition to a group of people in revolt against their government until they were “virtually an independent community according to the principles of international law.” Two conditions were vital: First, the “community claiming to be independent should have a Government of its own, receiving the habitual obedience of its people.” Second, the insurgents' “habit of obedience” to the old government must have stopped as a result of a severed relationship. Lewis urged caution: “It is easy to distinguish between day and night; but it is impossible to fix the precise moment when day ends and night begins.” The great English legal scholar John Austin noted that “it was impossible for neutral nations to hit that juncture with precision.” The British government must not bestow recognition if it saw any “reasonable chance of an accommodation.” According to international law, it must withhold any action while a “bona fide struggle with the legitimate sovereign was pending.”36

The war's verdict, Lewis argued, remained undecided. Part of the proof for this claim lay in the Union's resort to black liberation. The Lincoln administration had termed the Emancipation Proclamation a military action that, Lewis charged, was “intended to impoverish and distress the Southern planters, possibly even to provoke a slave insurrection.” Additional evidence of the ongoing war was the Confederacy's continued pleas for recognition. “If the independence of the seceding States was equally clear, they and their English advocates would not be so eager to secure their recognition by European Governments.” Premature intervention would make England an ally of the Confederacy and lead to war with the Union. Intervention came laden with problems. “If the Great European Powers are not contented to wait until the American conflagration has burned itself out, they must not expect to extinguish the flames with rose-water.”37

The neutral nations, Lewis admitted in a concession to Russell's claim, could justify a forceful intervention only if the fighting had so badly damaged them economically that it threatened their survival. To stop the loss of life or to secure cotton, international law condoned “an avowed armed interference in a war already existing.” The “Southern champion” (Napoleon) wanted an “armed mediation” or “dictation.” Such a step, Lewis later acknowledged, might have been advisable, but this was not what the proponents of “moral force” intended. No one spoke of “coercing the North a few weeks ago.” Foreign governments had advocated using their “good offices” in seeking peace. If mediation failed, however, they could follow the law of nature in judging the merits of the struggle and helping the party believed to be in the right if that party asked for assistance or accepted it.38

But, Lewis warned, the use of force guaranteed monumental problems that raised the question of whether intervention was “expedient.” England, France, Russia, Austria, and Prussia (assuming they cooperated in the effort) would confront great logistical difficulties in moving armed forces across the Atlantic. How would their wooden ships fare against the Union's ironclads? If the intervening nations brought an end to the war, did they have peace terms capable of maintaining that peace? A “Conference of Plenipotentiaries of the Five Great Powers” would have to meet in Washington, D.C., to negotiate a settlement. “What would an eminent diplomatist from Vienna, or Berlin, or St. Petersburg, know of the Chicago platform or the Crittenden compromise?” The “Washington Conference,” as Lewis called it, would confront numerous other questions after it presumably settled the independence issue. Boundaries? Partition of the western territories? Slavery both in the South and in the territories? Navigation of the Mississippi River? “These and other thorny questions would have to be settled by a Conference of five foreigners, acting under the daily fire of the American press.”39

Would the powers retain their cooperative arrangement once the war ended and its spoils became available? “In the same proportion that, by increasing the number of the intervening powers, you increase the military or moral force of the intervention, you also multiply the chances of disagreement.” A five-power mediation would be “an imposing force,” Lewis conceded, “but it [was] a dangerous body to set in motion.” The sovereigns would not only have to satisfy the Union and the Confederacy but themselves as well. The arbiters might dispute with each other, “and this well-intentioned intervention might end in inflaming and perpetuating the discord.” England would have a “peculiar interest” in North America that the other four powers did not share. England and France could find themselves on one side against the others. “England might stand alone.”40

Lewis had presented a powerful argument against intervention. Involvement in another country's affairs always guaranteed complex problems, the most important being the chances of causing a war with either or both antagonists. That northerners and southerners had gone to war constituted strong evidence that no outside power could devise peace terms that satisfied both sides. Either that power must stay out of the conflict and let the battlefield yield the verdict, or it must engage in a forceful intervention whose ramifications could spread beyond the present war.

Gladstone's spirited speech calling the Confederacy a nation had launched a national debate over intervention that forced the Palmerston ministry to confront an issue having enormous implications for both sides in the American war. The main focus was the widespread destruction and loss of life in a contest without meaning, one that would not have happened had the Union recognized its inability to subjugate the Confederacy. The British now faced the awesome prospect of risking conflict with one or both American antagonists by attempting to stop an atrocious war that damaged other nations, or simply ignoring its obligation as a civilized nation and allowing the war to wind down on its own. Particularly noteworthy was the absence of slavery from the discussions both outside and within the halls of government, but that did not mean the issue was inconsequential. Nor was the possibility of a French-led intervention totally advantageous to the Confederacy. Napoleon III had long sought to fulfill his illustrious predecessor's dream of reestablishing a French Empire in the New World following its humiliating withdrawal from the Continent after the French and Indian War. Only at the Confederacy's expense could he acquire the territory needed to flesh out his Grand Design.

On November 11, Russell convened a cabinet meeting that stretched over two days and focused on the issues raised in Lewis's memorandum. The foreign secretary recognized the problems inherent in intervention but made no attempt to deal with them. He had wrestled with these same matters while trying to justify his own proposal in October, and he knew that Napoleon's involvement in this new interventionist venture had erected additional obstacles. Rumors had already hit the London streets about a tripartite intervention proposed by the emperor and comprised of England, France, and Russia. In this uncertain atmosphere, Russell opened the meeting by announcing that the previous day the French ambassador had forwarded an invitation from Napoleon to join France and Russia in asking the two warring parties in America to accept a six-month armistice and a suspended blockade to provide an opportunity to reach a peace settlement. Russia refused to participate on an official basis but, according to a note just received from the British ambassador in St. Petersburg, had agreed to support any Anglo-French effort that the Union found satisfactory. Russell understood that Russia's conditional acceptance—requiring the Union's highly unlikely compliance with the proposal—was tantamount to a refusal. But he warned that British rejection of the armistice plan might encourage Russia to reverse its position and join France in an attempt to break up the Anglo-French relationship. He therefore recommended British cooperation with the French as a way to maintain their entente cordiale and as an incentive to peace proponents in the Union.41

The ensuing discussion quickly became hot and divisive. Palmerston briefly highlighted the positive features of the French proposal, but his support was, according to Lewis, not “very sincere” and “certainly was not hearty.” British participation, the prime minister declared, would demonstrate to suffering mill workers the ministry's concern over their plight. Lewis countered that the outcome might be just the opposite. British focus on the American problem could suggest the government's “indifference” to their problems. The proposal then went to the cabinet, which, Lewis wrote, “proceeded to pick it to pieces.” Every member except Gladstone and Baron Westbury “threw a stone at it.” The blockade proposal was “so grossly unequal, so decidedly in favour of the South,” that even Russell admitted that the Union would turn it down. Lewis had failed to grasp the prime minister's position—that he opposed the timing of an armistice offer but not the offer itself—and later recorded that Palmerston had broken with Russell once the cabinet's overwhelming opposition became clear. Gladstone, too, had not comprehended the cautious support for intervention in his two colleagues' stance and felt betrayed. Russell had “turned tail … without resolutely fighting out his battle,” whereas Palmerston had given him only “feeble and halfhearted support.” Sensing impending victory, Lewis concluded that Russell's “principal motive was a fear of displeasing France, and that Palmer[ston's] principal motive was a wish to seem to support him.”42

The outcome was predictable. At the end of the day, the cabinet overwhelmingly voted against the French proposal and asked Russell to write a note to Napoleon informing him of the decision. The foreign secretary (“under protest,” Lewis asserted) agreed to undertake the task. The cabinet would reconvene the following morning to review the draft.43

Russell managed to word the note in such a manner as to leave open the chance for an intervention. The destruction of the war, he wrote, had affected not only the two American antagonists but also the European observers. The French proposal was laudable for attempting to “smooth obstacles, and only within limits which the two interested parties would prescribe.” Indeed, it might cause the two sides to consider laying down their arms. His government's rejection of the proposal, Russell continued, did not signify an end to British cooperation with the French on “great questions now agitating the world.” Had not the Paris government “assisted the cause of peace” in the Trent crisis? The Palmerston ministry, however, had decided there was “no ground at the present moment [emphasis added] to hope that the Federal Government would accept the proposal suggested, and a refusal from Washington at present would prevent any speedy renewal of the offer.” It urged a close following of American public opinion to determine whether a tripartite “friendly counsel” might become appropriate in the future.44

Russell's carefully crafted reply to Napoleon's proposal, with the cabinet's approval, implied four times that intervention might become acceptable at some time in the war. Gladstone triumphantly wrote his wife that the response was “put upon grounds and in terms which leave the matter very open for the future.” Palmerston likewise voiced no opposition to the draft, demonstrating again his resistance to the timing but not to an intervention itself. Lewis admitted that the cabinet decision “was only provisional.” Lyons, too, approved the cabinet's action and assured Russell that the Union would have rejected Napoleon's proposal.45 Russell had not given up on intervention but had adopted Palmerston's wait-and-see posture—that the outside powers would refrain from stepping in until the fortunes of the battlefield had convinced the Union that it could not subjugate the Confederacy. Perhaps most if not all cabinet members and Lyons agreed with this stand, objecting to the proposed intervention primarily because it had come from Napoleon.

If so, the ministry's suspicions of Napoleon's motives were justified, for his ambitions extended beyond a humanitarian desire to end the American conflict. The emperor knew the Union could not accept the plan without abandoning all hope of defeating the Confederacy. To throw open southern ports during an armistice would permit the enemy to stockpile matériel and resume the war fully armed. But a forcefully reopened cotton trade would alleviate the widespread suffering of his own people. And, as Dayton later observed, even if the emperor failed to acquire cotton, his effort would let his distressed people know he had tried. Two contemporaries on opposite sides of the American conflict believed that Napoleon had more in mind. Dayton from the Union and De Leon from the Confederacy both thought that Napoleon had intended his armistice offer to curry southern favor and thereby promote his expansionist goals in Mexico. Southerners and the French, Dayton warned Washington, would find mutual benefits in working together. The emperor thought southern separation probable and would believe that his policy had helped bring it about. De Leon also argued that Napoleon had used the proposal to win moral standing among Europeans—hence, his attempt to put England and Russia in an awkward position by having the offer published in the Moniteur on November 13 before they could reply. After the British and Russians rejected the proposal, the Moniteur, again speaking for the emperor, attempted to salvage the situation by insisting that their actions “did not constitute a refusal, but only an adjournment,” and that “the hesitations of the Cabinets of London and St. Petersburg are apt soon to terminate. A feeling prevails in America, North as well as South, favorable to peace, and that feeling gains ground daily.”46

Napoleon had several reasons for advocating this armistice proposal, but he mainly sought to tie the Confederacy to his Mexican project. Economic problems in France had placed him under great political pressure to help end the American war and reopen the cotton flow so crucial to his industrial program. His Conservative supporters wanted to stop the “needless effusion of blood” and help Europeans in economic distress. Liberal proponents of the Union countered that intervention would favor the Confederacy and meet rejection by the Lincoln administration. Restoration of the Union, they argued, was the best way to secure cotton. But Napoleon's proposal rested on the belief—shared throughout France—that neither antagonist would prevail, along with his calculation that an armistice would win Confederate favor and facilitate his aims in Mexico.47

In the meantime, the American legation in London heard rumors of a French interventionist proposal that Adams, unaware of the secret meetings at the Palmerston ministry to discuss the matter, at first dismissed as nonthreatening even if true. Russell, after all, had assured him that neutrality remained the government's policy and that he would inform the minister if anything changed. The day after the cabinet's deliberations, however, the Times published the French offer (the same day it appeared in the Moniteur) with the assertion that the Palmerston ministry had only placed intervention on hold and that “the present is not the moment for these strong measures.” Not only had the French presented a proposal, but also the Palmerston government had discussed it. Furthermore, the ministry had left the issue open for future consideration. Clearly, Adams reacted to these explosive revelations with mixed emotions: indignation over Russell's apparent false assurances of neutrality, anger that the European powers had considered a forceful intervention in American affairs, and surely a bitter sense of relief tempered by alarm that the proposal had failed but only for “the present.”48

Two days later, on November 15, Russell (while keeping his own position private) calmed the minister with another carefully crafted statement of truth—that the cabinet “never intended agreeing to the mediation.” That same day the Russian government publicly turned down the French proposal (though he privately instructed Stoeckl that if France and England went ahead with a mediation offer, he was “to lend to both his colleagues, if not official aid, at least moral support”). Despite the Times's suggestion that the French offer remained a possibility, Adams felt confident after their public disavowals of the French venture that the British and the Russians would reject similar proposals in the future. Russell, Adams believed, had been forthright and honest, and the Russian ambassador in London, Baron Philip Brunow, had made every effort to maintain friendly relations with the Union. Moreover, a recent article in Russia's semiofficial organ, the Journal of St. Petersburg, had expressed the same sentiments.49

The ever-suspicious assistant secretary, Benjamin Moran, did not feel assured. He called the French offer “a piece of weak insolence” that had originated from that “prince of intriguers Slidell.” Also on November 15, word arrived from the American legation in Paris that Drouyn had earlier stated that if England and Russia rejected it, the proposal would die. “I hope so,” Moran tersely remarked.50

The Lincoln administration, however, was infuriated on learning that the French and the British had discussed a proposal for intervening in American affairs. Seward seethed with anger as he specifically asked Lyons to make the Union's resentment known to Mercier. Only the Russians had understood the Civil War as America's business—not the Europeans'. Anglo-French interest in mediation, Seward told Adams, substantiated Napoleon's “aggressive designs” in North America. Lincoln remained cautious about taking on additional problems in the midst of the Civil War and discreetly attributed the French proposal to a “mistaken desire to counsel in a case where all foreign counsel excites distrust.” But whatever its roots, the offer had raised southern hopes and assured a longer war. “This Government will in all cases,” Seward wrote Dayton in Paris, “seasonably warn foreign Powers of the injurious effect of any apprehended interference on their part.” After the fighting was over, “the whole American people will forever afterward be asking who among the foreign nations were the most just—and the most forbearing to their country in its hour of trial.”51

The Confederacy also reacted bitterly to the episode, although for different reasons. Francis Lawley, the pro-Confederate correspondent for the Times, witnessed firsthand the disappointment felt in Richmond. Like many southerners, he tied England's refusal to the existence of slavery and found it difficult to believe that that single institution could prove so decisive. Once independent, the Confederacy would be in a better position to resolve that problem than if it rejoined the Union and continued to be “on the defensive” with abolitionists. The Index was livid over the British reluctance to act: “Has it come to this? Is England, or the English Cabinet, afraid of the Northern States?”52

Both American antagonists mistakenly thought Russell the chief obstacle to British intervention. Years later, Adams remained unaware of the foreign secretary's support for British involvement in the war and fondly recalled his strong resistance to the measure. Russell was a leader of “unquestioned integrity,” making it “fortunate I had just such a person to deal with during my difficult times.” In 1868 Adams recorded in his diary that Russell had brought the French proposal before the cabinet “with his own opinion adverse to it. It had then been declined without dissent.” The view was no different from the Confederate side. Slidell and the Index were likewise ignorant of Russell's real sentiments and blasted him for opposing Napoleon's proposal.53

Some contemporaries, however, compounded Adams's mistake in judgment by attributing England's rejection of intervention to Palmerston as well as Russell. According to the Richmond Whig, the prime minister and his foreign secretary were “two old painted mummies” who had sought to prolong the war until it destroyed both Union and Confederacy. Harcourt also demonstrated an amazing lack of astuteness in finding Palmerston equally responsible for blocking intervention. He thought it a “little amusing that the whole wrath of the South and the imputation of being the real obstacle to Intervention should fall on Lord John. It only shows how little is known of the real history of affairs. Probably when the history of 1862 is written,” he observed in a letter to Lewis, “it will be apparent that Ld. Palmerston and Russell were the two men who decided the question against interference. It reminds me of what Sir R[obert] Walpole said[:] ‘Don't tell me of History[;] I know that can't be true [Harcourt's emphasis].'”54

Russell and Gladstone had always been the strongest proponents of immediate British intervention, whereas Palmerston (and some if not most cabinet members) had wanted to hold off until both American antagonists had realized the futility of continuing the war. But the interventionist sentiments of the prime minister and his foreign secretary remained hidden behind the policy of neutrality, while the chancellor had trumpeted his feelings both publicly and privately. Palmerston and Russell had wanted to remain neutral until the Union realized that it could not subjugate the Confederacy and that mediation had become necessary. The foreign secretary, however, did not want to wait any longer. When the moment for mediation never came, Russell supported Napoleon's armistice plan even though it included the potential for force. The growing bloodshed sickened the secretary; that carnage combined with the burgeoning cotton famine caused him to support any approach that offered the slightest hope for success. Palmerston only lukewarmly discussed the merits of Napoleon's project but did not rule out intervention. In mid-December 1862, the prime minister assured Russell that the government could extend recognition “with less Risk in the Spring” to the safety of Canada. He told King Leopold that England would have accepted the French proposal if it had had a chance for success. Intervention in two to three months might work. Gladstone, however, opposed a further delay because of the rising atrocities of the war and the rapidly spreading economic misery at home. To New York financial magnate Cyrus Field in New York, Gladstone insisted that “this destructive and hopeless war” had to end. “Is this not enough?”55

Slidell, meanwhile, had uncovered part of the truth about the Confederacy's real supporters in the British government and now felt more certain about French action. The “entente cordiale,” he thought, had collapsed because of growing French distrust of the British. Napoleon had expected London to comply with his October 30 proposal and, failing that, would act on his own in the next few weeks or months. “Who would have believed,” Slidell asked Mason in November 1862, “that Earl Russell would have been the only member of the Cabinet besides Gladstone in favor of accepting the Emperor's proposition?” Palmerston, Slidell mistakenly believed, had been the main barrier to intervention.56

Slidell was correct in expecting a greater French push for intervention: The question soon became entangled in the slavery issue and in Napoleon's imperial interests in Mexico. In turning the war in an antislavery direction, the Lincoln administration had confronted the Confederacy with its greatest threat. Not only did the president hope that emancipation would eventually knock out the chief cornerstone of the South's existence, but he also counted on increasing its difficulties in securing outside assistance in the war. The Confederacy, of course, was well aware of the challenge that emancipation posed to foreign intervention, but what both antagonists failed to realize was that the changed orientation in the war had thoroughly angered the British and increased the impetus for Anglo-French involvement. Yet even as this anger worked in the Confederacy's favor, another danger threatened its future: Its willingness to negotiate a devil's bargain with Napoleon would open the door for his imperial interests in the Western Hemisphere. The British, he had learned from the failed armistice proposal, would not intervene in American affairs and most certainly would do nothing to obstruct his intentions in Mexico.

President Davis, too, ignored Napoleon's past record of treachery and remained optimistic about winning French recognition. To a crowd in Jackson, Mississippi, on the day after Christmas, he declared: “We have expected sometimes recognition and sometimes intervention at the hands of foreign nations, and we have had a right to expect it.” Never in history “had a people for so long a time maintained their ground, and showed themselves capable of maintaining their national existence, without securing the recognition of commercial nations.” Although it was unwise to depend on foreign governments, there were encouraging signs from abroad. “England still holds back,” but France seemed ready to extend “the hand of fellowship.” If so, “right willingly will we grasp it.”57

In Washington, Lincoln considered the Emancipation Proclamation integral to his initial goal of preserving the Union and then, as the war progressed, to improving that Union along with stemming the interventionist urge. In terms of the war, he asserted his authority as commander in chief to employ any method necessary to achieve victory. On legal grounds, he pronounced slaves free only in states still in rebellion. Lincoln knew that only a constitutional amendment could end slavery, but he also recognized the importance of creating an atmosphere conducive to such a momentous change. Finally, for diplomatic reasons, he used emancipation to curtail the chances for foreign intervention. Critics at home and abroad denounced the document for lacking moral fiber, but they failed to consider its broad impact as the first major step taken by the federal government against slavery. Even Stoeckl joined the chorus of skeptics, grousing that the administration had issued an “impolitic and impractical” decree intended to incite slave insurrections in the South. Once the Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, Lincoln hoped, the call for black freedom would become integral to the establishment of a more perfect Union. Emancipation would finally mesh with liberty and, with Union, become one and inseparable.58

Jefferson Davis also grasped the significance of the Proclamation in terms of its potential impact both at home and abroad. The measure, he insisted, meant that “several millions of human beings of an inferior race, peaceful and contented laborers in their sphere, are doomed to extermination, while at the same time they are encouraged to a general assassination of their masters by the insidious recommendation ‘to abstain from violence unless in necessary self-defense.'” British and French neutrality had already prolonged the war and resulted in “scenes of carnage and devastation on this continent, and of misery and suffering on the other, such as have scarcely a parallel in history.” In refusing to treat the Confederacy as independent, these nations had emboldened the Union to believe it could conquer the Confederacy. Lincoln had now directed the war onto a path that would lead to one of three consequences: the slaves' extermination, the exile of all whites in the Confederacy, or complete separation from the United States.59

The mixed reaction to Lincoln's call for emancipation revealed a widespread failure to grasp the long-range thrust of the document. Some observers ridiculed the lack of eloquence in his words and the absence of a moral condemnation of slavery. Count Adam Gurowski, Harvard professor of international law and translator for the U.S. State Department, remarked that the Proclamation was “written in the meanest and the most dry routine style; not a word to evoke a generous thrill, not a word reflecting the warm and lofty … feelings of … the people.” Karl Marx, coauthor with Friedrich Engels of the Communist Manifesto in 1848 and now correspondent for a London newspaper, likewise decried the document's terse tone.60

But Marx's attack actually highlighted the Proclamation's greatest strengths. He conceded that the “most formidable decrees which [the president] hurls at the enemy and which will never lose their historic significance, resemble—as their author intends them to—ordinary summons, sent by one lawyer to another.” Skeptics unfairly denounced Lincoln for freeing the slaves only in areas where he had no jurisdiction; the truth was that he acted correctly in freeing them in regions that fell within his domain as a commander in chief exercising his war powers. In exempting the Border States, his sole purpose was to restore “the constitutional relation between the United States, and each of the states, and the people thereof.”61

The British attitude toward the Proclamation gradually changed, suggesting that the Lincoln administration had finally achieved its central objective in foreign affairs of keeping England out of the war. British indignation over the missing moral principles steadily gave way to the realization that the Confederacy's defeat necessarily meant slavery's demise. Foresighted spokesmen such as Argyll, Bright, and Cobden had made this argument on the eve of emancipation, but they had failed to convert their colleagues. In early October 1862, however, the Morning Star of London broke with Lincoln's critics. The Emancipation Proclamation marked “a gigantic stride in the paths of Christian and civilized progress … the great fact of the war—the turning point in the history of the American Commonwealth—an act only second in courage and probable results to the Declaration of Independence.”62

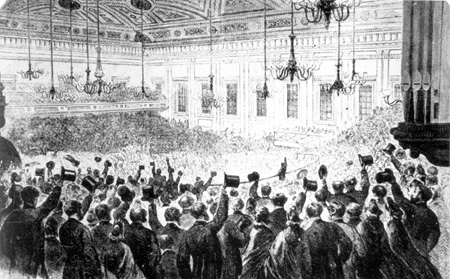

Union and Emancipation meeting in Exeter Hall, London (Harper's Weekly, March 14, 1863)

Workers north of London, too, had praised the U.S. president's action, spurred by the presence of nearly forty African Americans from the Union who advocated its cause by lecturing and holding meetings that exalted the movement against slavery. In huge, highly charged rallies beginning in December 1862, British labor groups cheered Lincoln for promoting the rights of people everywhere. His preliminary Proclamation encouraged the establishment of pro-Union clubs such as the Committee on Correspondence with America on Slavery to resist recognition of the Confederacy, and the Union and Emancipation Society in Leicester, which included a large number of workers who condemned slavery as a violation of liberty. “The great body of the aristocracy and the commercial classes,” Adams observed from the embassy, “are anxious to see the United States go to pieces,” whereas “the middle and lower class sympathise with us.” They “see in the convulsion in America an era in the history of the world, out of which must come in the end a general recognition of the right of mankind to the produce of the labor and the pursuit of happiness.” Adams received countless letters, petitions, and resolutions from labor organizations and emancipation societies, all lauding the president. The public outpouring for emancipation virtually muted the southern sympathizers in England.63

Lincoln also helped shape British workers' opinions on the war. Charles Sumner, who had many contacts in England, worked closely with the president in writing notes to textile workers expressing concern over unemployment and blaming the cotton shortage on the Confederates—“our disloyal citizens.” Self-interest, Lincoln wrote workers in Manchester, could easily have drawn them into the Confederate camp; instead, they acted on high principles in supporting the Union. This was an example “of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country.” To workers in London, Lincoln declared the war a test of “whether a government, established on the principles of human freedom, can be maintained against an effort to build one upon the exclusive foundation of human bondage.”64

By early 1863, however, the British government realized that the White House's move against slavery, regardless of the motive, had made intervention even more difficult to endorse. Southern enthusiasts outside British governing circles remained active, establishing organizations such as the Manchester Southern Independence Association, the London Southern Independence Association, and the London Society to Promote the Cessation of Hostilities in America. But, as shown earlier, the appearance of widespread popular support for the Confederacy was deceptive. Even Russell had grown weary of the struggle, writing Lyons in mid-February that “till both parties are heartily tired and sick of the business, I see no use in talking of good offices.” William Gregory felt the same way. Although he had been the first vocal supporter of intervention in 1861, he now gloomily told Mason that the House of Commons opposed any such action as “useless to the South” and a possible cause of war with the Union. “If I saw the slightest chance of a motion being received with any favour I would not let it go into other hands, but I find the most influential men of all Parties opposed to it.”65

The war, meanwhile, offered no solution to the overarching objective of stopping the bloodshed. Two major battles in December 1862 and early 1863 had failed to break the will of either antagonist—Fredericksburg in Virginia, which resulted in a devastating Union defeat, and Murfreesboro or Stones River in Tennessee, which ended in a narrow victory for the Union. The engagement at Murfreesboro left the northern Army of the Cumberland unable to take the offensive for months after sustaining the highest casualty rates of the war in relation to the numbers fighting. The slaughter at Fredericksburg particularly bedeviled the Union, heightened by a mid-December cabinet crisis driven by Chase's efforts to remove Seward, one that Lincoln masterfully defused. “If there is a worse place than Hell,” the president moaned in the midst of these troubles, “I am in it.”66

For the moment, however, he had to maintain the fight by enlarging the Union army and raising his people's morale. The Union's shattering defeat at Fredericksburg had combined with the shared butchery at Murfreesboro to force the administration to institute a military draft. As it went into effect on March 3, 1863, Lincoln fervently defended the war effort as a necessary baptism by blood that would renew hope. At the end of the month, he issued a presidential proclamation that established a national day of fasting on April 30 and appealed to higher principles in justifying such a terrible war. “Insomuch as we know that, by His divine law, nations like individuals are subjected to punishments and chastisements in this world, may we not justly fear that the awful calamity of civil war, which now desolates the land, may be but a punishment, inflicted upon us, for our presumptuous sins, to the needful end of our national reformation as a whole People?”67

The president's new emancipation policy inspired black enlistment in the Union army, which conjured up the Confederacy's worst nightmare: ex-slaves killing their white masters. In March 1863 Lincoln wrote Andrew Johnson, military governor of Union–occupied Tennessee: “The bare sight of fifty thousand armed, and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi, would end the rebellion at once. And who doubts that we can present that sight, if we but take hold in earnest?” By autumn fifty thousand blacks would be in uniform, prompting the president to declare publicly that “the emancipation policy, and the use of colored troops, constitute the heaviest blow yet dealt to the rebellion.”68

Lincoln continued to insist that the chief justification for the Proclamation rested on its military usefulness. In that way, he told Chase, emancipation had a constitutional or legal base. “If I take the step must I not do so, without the argument of military necessity, and so, without any argument, except the one that I think the measure politically expedient, and morally right? Would I not thus give up all footing upon constitution or law?” Yet Lincoln's emphasis on military necessity had become inseparable from emancipation, tying antislavery to the war effort and eventually convincing the British and the French that the Proclamation waged an all-out war on the Confederacy that could only end with its unconditional surrender and the death of slavery.69

Only in this manner can one understand the strong reaction to emancipation by both northerners and southerners, along with their equally intense feelings toward foreign intervention. Each side considered itself the principal defender of republicanism. Both called for self-government and liberty in combating tyranny—whether emanating from the government in Washington (the Confederate view) or from white slaveholders below the Mason-Dixon Line (the Union view). Above and below that line, the staunchest supporters of the war considered the republic in peril and sought to preserve its heritage as the true progenitors of the American Revolution. From the Union's perspective, emancipation defined northerners as patriots and southerners as traitors. To the Confederacy, emancipation constituted the first step in a long-range program to squelch states' rights, thereby defining northerners as traitors and southerners as patriots. Such was the central paradox of the Civil War.