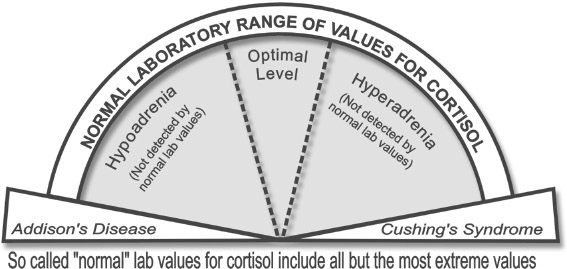

None of the standard laboratory tests typically used by most doctors are designed to detect adrenal fatigue in its varying degrees of severity. (For more on this topic see the section below on “Problems in the Interpretation of Laboratory Tests.”) Although it is possible to use several standard blood and urine tests to look for indications of hypoadrenia, their interpretation is inexact. The “normal” range for adrenal function on standard blood and urine tests includes everything but the most severe cases of adrenal malfunction, such as Addison’s disease (extreme low) and Cushing’s Syndrome (extreme high). So unless your hypoadrenia is this severe, your doctor will interpret your test results as indicating your adrenal function to be within the normal range.

However, there is a relatively new lab test that accurately measures several hormones, and is especially useful for measuring several of the adrenal hormones. It is called saliva hormone testing.

Saliva hormone testing measures the amounts of various hormones in your saliva instead of in your blood or urine. It is the best single lab test available for detecting adrenal fatigue and has several advantages over other lab tests in determining adrenal hormone levels. Saliva hormone levels are more indicative of the amount of hormone inside the cells where hormone reactions take place. Blood, on the other hand, measures hormones circulating outside the cells, and urine measures the spill over of hormones out of the blood and into the urine. Although blood and urine hormone tests have their uses, neither of them correlates with the hormone levels inside the cells. The level of a hormone circulating in the blood or excreted in the urine does not necessarily reveal how much of that hormone is getting into the cells. However, saliva testing for hormone levels is simple, accurate and reliable, and many studies have confirmed its accuracy as an indicator of the hormone levels within cells.

Besides providing this nice little peek at hormone levels inside the cells, saliva tests are easy to perform. All you have to do is spit into a small vial. The tests are non-invasive (no needles) and you do not even have to go to a laboratory to complete them. This means that they are an extremely useful way to monitor your degree of hypoadrenia and your progress over time because they can be repeated as often as needed. Saliva tests are also less expensive than blood tests for hypoadrenia. They can be done by many health practitioners, other than medical doctors, such as chiropractors and naturopaths, who may not have laboratory privileges in your state, but who perhaps know much more about adrenal fatigue than your family doctor or specialist. Some labs will run this test for you without a physician’s signature, so it is possible to order the kit and do the test yourself. You can even obtain a saliva kit by mail and then send it back to the lab from anywhere in the United States. However, unless you know how to interpret a hormone test, it is far better to have a health practitioner familiar with saliva tests and adrenal fatigue do the interpretation for you. The health practitioner’s experience and understanding of how particular test results relate to your whole health pattern is something that is difficult to provide yourself. In this case it is important to find a practitioner who has experience with adrenal hormone testing and interpretation, which is unfortunately not a procedure widely known to mainstream doctors.

The best way to determine your particular adrenal hormone (cortisol) levels is to use the saliva test that measures your cortisol levels several times per day. Typically, laboratories testing hormonal content of saliva have test kits that take samples four or more times per day. You merely carry around a few small tubes and, at designated times of the day, you spit into one of the tubes and recap it. The samples usually do not need to be refrigerated and can be sent by mail to the laboratory. For a list of laboratories that do accurate and reliable saliva testing, as well as a list of doctors familiar with this test, see our website at www.adrenalfatigue.org . By measuring your saliva hormone levels at least four times per day, you will be able to see for yourself where your cortisol levels are compared to the norms. After you receive your report, you can see whether low cortisol levels are responsible for the feelings of fatigue that you experience during particular times of day. Because saliva hormone levels correlate well with the amount of hormone inside the cells (tissue levels) and samples can be taken as needed without inconvenience or adverse side effects, saliva testing is often more useful than blood or urine testing of hormone levels.

How I Use the Saliva Hormone Tests

I use the saliva hormone test to confirm other signs and symptoms of adrenal fatigue. I start with a saliva cortisol screening test that measures cortisol levels at four different times during the day: between 6:00-8:00 AM (within 1 hour after waking) when cortisol levels are highest; between 11:00-12:00AM; between 4:00-6:00 PM; and between 10:00-12:00 PM. This shows how your cortisol levels vary during the day (something else you cannot easily do with blood or urine tests).

In addition, if I have a patient whose main symptom is fatigue and their questionnaire is inconclusive, or if someone has intermittent symptoms, I use the saliva test to determine if their symptoms are related to low adrenal function. Sometimes I have patients carry around some test vials with them so they can take saliva samples while they are experiencing a low period or other symptoms, at any time during the day. On each saliva sample they write the date and time. They also record, along with the date and time, information on a separate sheet of paper and send the vials off to the lab. When I get their test results back, I compare their saliva cortisol levels with the laboratory standards for the time they are experiencing symptoms. If the cortisol levels are low at those times, we know that low adrenal function is involved in the symptom picture. This gives me a way to assess adrenal activity at the time they were experiencing a symptom.

Another way I like to use the saliva test, when possible, is to compare samples taken when a patient is experiencing an energy high or low with samples taken during a regular day, when the patient is feeling relatively normal (baseline samples). After we have a baseline, these patients carry around some spare vials to take saliva samples at times when they are feeling especially good or especially bad. Again, they record the symptom(s) they were experiencing as well as the date and time (on a separate sheet of paper). They also record the date and time on each vial and send them off to the lab. This is an excellent way to determine whether the lows and highs you experience correspond to relatively low and high cortisol levels. To my knowledge, no other physician uses this method, but it is quite a handy method of determining cortisol levels in relation to symptoms.

I also usually measure DHEA-S levels with the saliva test as well because the adrenals are the primary source of DHEA-S (but not necessarily DHEA). Adrenal fatigue syndrome often involves decreased DHEA-S. The DHEA-S level is a direct indicator of the functioning of the area within the adrenal glands that produces sex hormones (the zona reticularis). Saliva tests for testosterone, the estrogens, progesterone and other hormones can also be done, if needed, and may be of value in working with adrenal fatigue. Testosterone and DHEA-S levels are two of the most reliable indicators of biological age. Testosterone and DHEA-S levels below the reference range for the person’s age may be indicators of increased aging. If the cortisol levels are also decreased, the 3 tests together further indicate chronically decreased adrenal function.

The Effect of Transdermal Hormone Replacement on Lab Results

When using transdermal replacement hormones (hormones applied through the skin, such as progesterone cream), the saliva values for those particular hormones frequently rise out of the testing range. These hormone levels will remain abnormally high on saliva tests until a few months after you stop applying them. Blood tests, on the other hand, will not reflect tissue levels of the transdermally applied hormone creams because the hormones from the creams are transported through the lymph to the cells rather than through the blood. The blood levels will not change even though more hormone is getting into the cells. So if you are using transdermal hormones, neither blood nor saliva test results are accurate indicators of your tissue levels. In this case, your symptoms (or lack of) rather than lab tests are better indicators of your own hormonal output. Symptoms are very closely related to tissue hormone levels of most hormones.

Similarly, if you use topical cortisone or related preparations, it is best to have a period of non-use of 1 week or more to get accurate indicators of tissue cortisol levels from saliva tests. Like progesterone, cortisol and its synthetic analogs used in topical creams can falsely elevate saliva levels.

If a doctor does not use the saliva hormone tests, piecing together a correct diagnosis of adrenal fatigue from other laboratory tests is more difficult. Most laboratory tests are designed to look for “disease” states in the human body and adrenal fatigue is not a disease per se. In addition, there has never been a reliable urine or blood test that checks for, and can definitively diagnose, mild forms of hypoadrenia. Currently available laboratory tests can be useful in the diagnosis of adrenal fatigue, but they require special training in their interpretation. In fact, common tests done as part of a routine blood work-up can be very useful in the detection of signs of adrenal fatigue if physicians know what to look for. However, standard laboratory tests have certain limitations of which you should be aware.

Laboratory tests are usually based on a population of so-called “healthy” people. But the fundamental flaw in using these tests to diagnose adrenal fatigue is that these “healthy” people were never screened for mild to moderate hypoadrenia themselves. They were only screened for severe hypoadrenia, i.e. Addison’s disease. Thus the very standards to which laboratory tests compare patients are faulty from the outset because the population used to standardize the tests may include many people with some level of adrenal fatigue.

Another problem is that laboratory tests are defined and standardized according to statistical norms instead of physiologically optimal norms. That is, test scores are based on math rather than on signs and symptoms. When the adrenal function of a population is tested, all the individual scores are taken and averaged together. The resulting group average, called the “mean,” is then used to calculate what is called a probability distribution. In this case the probability distribution is a statistical prediction of how often each score will occur when the adrenal function of a group of people is tested. When all the scores are lumped together, this probability distribution looks like a bell (See illustration “The Normal Bell Curve”). The most frequent scores occur close to the mean, thus forming the dome of the bell. Less frequent scores occur further from the mean and so form the slope and skirt of the bell. Only the highest and lowest 2.5% of the scores are considered to be outside the “normal range” and therefore indicators of actual disease. As a result, this statistical model only catches extreme adrenal dysfunction and misses all the rest.

In adrenal function the extreme low is Addison’s disease and the extreme high is Cushing’s disease. The other 95% represents an enormous variation in levels of adrenal function that is usually disregarded by lab computers and overlooked by doctors because the scores in this range do not fall into either of the two extreme, or “diseased” categories. By default, any scores falling within this wide range (95%) are considered “normal” (See illustration “So-called normal laboratory values for cortisol include all but the most extreme value”). The end result of basing laboratory test scores on statistics rather than on signs and symptoms is that many people who have mild to moderately severe adrenal fatigue are never accurately diagnosed; they look “normal” on the tests. To make matters worse, standards can vary from lab to lab and therefore it is not always possible to even compare the results of one lab with another.

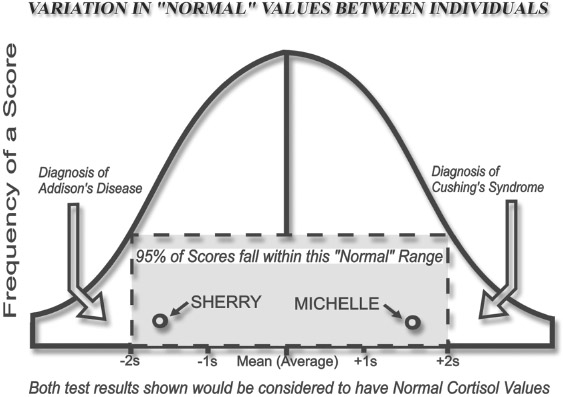

Additionally, standard laboratory tests also do not take into account the important factor of individual biochemical variation. One person’s test results can vary significantly from another person’s, with both test results being normal (See illustration “Variation in ‘Normal’ Values Between Individuals”).

This individual variation is not considered when scoring lab tests; you are either inside or outside the normal range. That means that your test score could even drop to ½ its normal value and still fall within the normal range. When your hormones drop to half their normal value, there are definite biochemical changes going on in your body, yet this may never show up as unusual on standard lab tests interpreted in the usual way (See illustration “Individual Variation of Blood Cortisol Values.”) This concern has been voiced in one of the most authoritative texts in medicine, Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. “Most hormones have such a broad range of plasma levels within a normal population. As a consequence, the level of a hormone in an individual may be halved or doubled (and thus be abnormal for that person) but still be within the so-called normal range.” (Fauci, Anthony S. et al. (Ed). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 14th ed. Vol. 1. McGraw-Hill, NY, p1970, 1998.)

Ideally, doctors would have baseline scores for each patient that had been obtained when the patient was feeling well and functioning at a healthy level. This way, when the patient becomes symptomatic and is functioning at a lower level, the test could be repeated and the resulting scores compared to the original scores. The difference would be quantifiable and the doctor could make an accurate judgment as to whether or not adrenal function in this patient is below his or her own normal. Perhaps future physicians truly interested in their patients’ health will do this.

There is also a significant problem associated with the way laboratory results are reported. Scores are sharply demarcated as falling either within the normal range or outside the normal range. There is no gray area. Most doctors have taught themselves to look only at those scores outside the normal range. These are clearly indicated on laboratory test printouts. Therefore, if Marsha received a score of 2.0 on a lab test where the normal range was 2.0-5.0, she would be considered normal. But if she scored 1.9, her test score would be considered abnormally low and would be flagged as such by the computer printing her test results. In the first case, the doctor would consider her normal, tell her as much, and ignore the actual score. If, on the other hand, her score was 1.9, the doctor would surmise that there is something wrong with Marsha because she got an abnormal score on the test and act accordingly. In the doctor’s mind at 2.0 she “didn’t have it” and at 1.9 she “did have it.” On most tests, laboratory error could account for more than the small difference between the 2 scores. It is important to realize that laboratory results are only indicators and that the actual scores, even when they fall within the normal range, may contain more useful information than “abnormal/normal.” I encourage you to obtain copies of all your lab tests so you can see for yourself the actual test values that indicate what is going on inside your body.

Further complicating the problem of proper interpretation of laboratory data in adrenal fatigue is the fact that steroid hormones occur in more than one form in your body but most lab tests measure only one. Cortisol, for example, takes on three forms in your blood: 1) unattached to any other substance (free), 2) loosely bound and 3) tightly bound to blood proteins. The most common measurement for hormones is the amount of hormone not attached to anything, called the free circulating hormone. However, this usually represents a meager 1% of the total amount of hormone available. It does not measure the bound hormones, which act as reserves and become free hormones if needed. This reserve can be critical to proper physiological function. For example, very low circulating cortisol levels can be brought to within normal range by the administration of a synthetic cortisol. But people taking synthetic cortisol cannot withstand stress as well as people with naturally normal cortisol levels, even though blood tests for both show normal free circulating cortisol levels. Part of the reason for this is that although their free circulating cortisol level is increased by taking the synthetic cortisol, there is still a lack of the reserve cortisol bound to different tissues in the blood that is made available in cases of emergency. Blood tests can often be deceptive because they do not typically give you the whole picture. Therefore, even though both healthy people and people taking cortisol might show normal free cortisol levels, their response to stress will probably differ considerably. The test results would give a very deceptive picture of “normal” in the case of the person receiving the drug, as it tests only the most superficial layer of cortisol availability.

Yet another problem with most laboratory tests is that many steroid hormones, such as cortisol, have notable hormonal fluctuations throughout any given day. Cortisol levels at noon are normally quite different than cortisol levels at 8:00 AM. However, many labs disregard the time of day samples are taken and compare them all to values standardized for 8 AM. Often I have had doctors send their patients back to a lab to have a cortisol test redone at 8:00 AM because no one had told the patient to have the blood test at 8:00 AM. Most hormonal tests, but especially adrenal tests, are standardized for 8:00 AM testing. So, unless otherwise indicated, always have hormone blood tests done at 8:00 AM.

Stress is another factor that significantly affects adrenal hormone levels. Your cortisol level tested after a quiet, relaxing morning will be very different from your cortisol level tested when you are under stress before you arrive at the lab. To obtain a typical value, have your test on a typical morning.

This is not to say that current laboratory tests are not useful for diagnosing adrenal fatigue but simply that it is important for you and the physician interpreting them to understand their limitations and appropriate uses. Listed below are some of the standard laboratory tests typically used to detect Addison’s disease that can also be useful for detecting milder forms of hypoadrenia if you know what to look for.

The 24-Hour Urinary Cortisol Test: An analysis known as the 24-Hour Urinary Cortisol Test measures the hormones excreted in your urine over a 24 hour period. This lab test can be helpful as an indicator of the output of several adrenal steroid hormones including corticosteroids, aldosterone and the sex hormones. Although the laboratory range of what are considered normal hormone levels is too broad to be of much value in diagnosing all but the most severe cases of hypoadrenia, if your hormonal output is in the bottom 1/3 of the “normal” range you can suspect hypoadrenia. When this result concurs with your responses to the questionnaire, the diagnosis is relatively certain.

The interpretive value of this test is limited because all the urine for a 24-hour period is pooled in one container. Consequently, it excludes the valuable information about surges or drops in hormone levels at specific times in the day which many people with adrenal fatigue experience. At one time of day cortisol levels may be normal or even high, and during another time of day they may drop to dramatically below normal. But because all the urine samples of the day are pooled in this test, the highs and lows often cancel each other out making the results look deceptively “normal.” To obtain specific information about your cortisol levels at particular times of day, do a saliva test.

Blood Tests: There are blood tests to measure circulating levels of the adrenal hormones aldosterone and cortisol, and others to measure the sex hormones related to adrenal function. But, by their very nature, blood tests divulge only the levels of the hormones circulating in the blood and do not reveal those inside the tissues, or potentially available to the tissues. However, when blood tests and urine tests are interpreted together by a trained practitioner who knows what to look for, a picture of your adrenal function can be pieced together, especially when the information is used in conjunction with your clinical presentation and medical history.

ACTH Challenge Tests:There is another kind of blood test, called an ACTH Challenge Test, which helps evaluate adrenal reserves and responsiveness and thus can help detect adrenal fatigue. In this test, baseline levels of circulating cortisol are first measured. Then a substance like Adrenal Corticotrophic Hormone (ACTH) that stimulates the adrenal output of hormones is injected. After the challenge substance is given, the circulating cortisol is re-measured to see how well the adrenals were able to respond to the stimulation. A normal response is for the blood cortisol levels to at least double. When cortisol levels do not double or rise only slightly, adrenal fatigue can be suspected. Although this test is usually done only if the blood cortisol levels are found to be low by some other indicator, I have known of instances in which the blood cortisol was well within the “normal” range, but failed to rise in response to the ACTH challenge. The ACTH Challenge Test has some value, even if cortisol levels are within the “normal” range, but it is important for the physician to realize that it is the reserve capacity of the adrenals and not their moment by moment response to stress that is being tested.

An alternative and more useful way of using the ACTH Challenge Test to detect adrenal fatigue is to combine it with the 24-Hour Urinary Cortisol Test. In this protocol, a 24-Hour Urinary Cortisol Test is given both before and immediately after the ACTH challenge. The results of the two 24-Hour Urinary Cortisol Tests are then compared. If the cortisol level of the second test is not at least double first, adrenal fatigue is present. This test can be a valuable indicator even if the first 24-hour test has cortisol values within the normal range.

There are several other blood and urine tests that can be of some use as indicators of hypoadrenia when used by physicians with special training. However, their value is limited and their interpretation is complex and beyond the scope of this book.

Although there are a few medical doctors who know how interpret these tests for adrenal fatigue, most do not. Even if they are willing to do the tests, most physicians will only pay attention to lab results that fall outside of the accepted norm, thus missing all but Addison’s disease or one of the even rarer diseases that cause severe hypoadrenia. Since your test scores will probably not be out of the accepted normal range, your doctor will tell you there is nothing wrong with your adrenals. What would be more accurate would be to say that your adrenals are not in failure or near failure. That is all that conventional interpretation of most urine and blood tests can determine. Single lab tests are merely separate pieces of a puzzle that must be assembled carefully before the hidden picture is accurately revealed. This is another reason why I prefer the saliva test; it gives clearer and more direct indications of hormone levels at the actual site where they are utilized – inside the cell. None of the blood or urine tests typically give you as much useful information about your adrenal fatigue as you will get from the combined use of the questionnaire, clinical self-tests described in this book, and saliva hormone tests.