Stress can kill. How do we learn to deal with it in a healthy way? To answer that, first let us look at the general adaptation syndrome and the role the adrenal glands and their hormones play in activating it. The general adaptation syndrome is the pattern of physiological adjustments your body makes in response to your environment (including your emotional environment). It has three phases: alarm, resistance and exhaustion which still function the same way in us as they did in primitive man, even though the stresses we face are very different. In this way our physical evolution has not kept pace with our social evolution. This means that our bodies create the same primitive response to a traffic jam on the way to work as early man’s did to being in front of stampeding antelopes; cortisol levels rise to increase energy production for greater physical effort. In primitive man this is just what was needed to deal with the situation but in a traffic jam there is no increased physical demand and the extra energy turns into anger or other sideways emotions instead. Likewise, when you face an angry boss your body reacts the same way it would to a snarling tiger; it prepares to fight or run. Unfortunately neither of these responses is appropriate in the office, and therein lies the source of many of the health problems attached to modern stress. Recognizing this will help you to understand much better why your body responds the way it does to stress and how to help minimize its harmful effects.

The initial response to the threat of a tiger or your boss is the alarm reaction, better known as the “fight-or-flight” response. This is your body’s answer to any kind of challenge or danger; a complex chain of physical and biochemical changes brought about by the interaction of your brain, the nervous system and a variety of different hormones. Your body goes on full alert. Instantly, it responds to the stress chemicals released into the blood stream, such as adrenaline, by increasing blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen intake, and blood flow to the muscles.

Here is what happens, blow by blow:

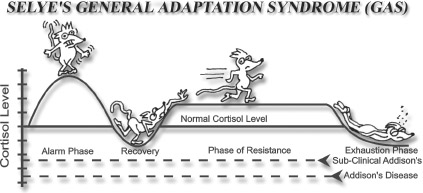

• Your boss, or the tiger, triggers an immediate “red alert” arousal in your hypothalamus, a little cluster of specialized cells at the base of your brain that controls all automatic body reactions [see illustration “Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS)”]. The hypothalamus is part of the limbic system, the primitive brain that influences unconscious, instinctive behavior relating to survival and reproduction.

• Your hypothalamus signals your pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH).

• ACTH instructs your adrenals to secrete epinephrine (adrenaline), norepinephrine (noradrenalin), cortisol and other stress related hormones. These hormones instantly mobilize your body’s resources for immediate physical activity.

• Your breathing becomes faster and shallower to supply necessary oxygen to your heart, brain and muscles; blood in the intestines is shunted to areas of anticipated need .

• Your cortisol levels rise and convert increased amounts of stored glycogen into blood sugar in order to provide more energy for the increased work your cells are required to do during stress.

• Adrenaline and noradrenalin (from the adrenal medulla) are released directly into your bloodstream to produce a surge of energy for your body.

• Your heart rate increases, blood vessels dilate, and blood pressure rises (all due to increased cortisol and adrenaline).

• You sweat more (cortisol).

• Muscle tension increases (cortisol, adrenaline and testosterone) throughout your body.

• Your digestion shuts down as blood is diverted away from your skin and stomach (hypothalamus). Digestive secretions are severely reduced since digestive activity is not necessary for counteracting stress (hypothalamus).

• Your bladder and rectum muscles relax. (In extreme stress, such as in battle, they may void their contents, “dropping the ballast,” so to speak).

For a few brief moments during the “fight or flight” response you may experience nearly super-human power to deal with the situation. One of the most famous instances of the incredible power of adrenaline occurred in Seattle some 35 years ago, when a woman driving with her baby was hit on the freeway. The car flipped over, flinging her clear and breaking her right arm as it pinned the baby beneath it. Over a dozen people who had rushed over to help witnessed this extraordinary event. The woman jumped up, ran to the car, lifted it with her left arm (that’s right, the whole car with one arm) and with her broken arm pulled the baby to safety. The baby, miraculously, was unharmed. The woman was admitted to a hospital with severe bruising on the left side of her body from the herculean feat and a broken right arm but she made a full recovery. The alarm stage is usually short lived. Typically the increased adrenaline level lasts a few minutes to a few hours and is followed by a drop in adrenaline, cortisol and other adrenal hormones that lasts a few hours to a few days, depending upon the magnitude of the stress.

After the alarm reaction is over, your body goes through a temporary recovery phase that lasts 24-48 hours. During this time there is less cortisol secreted, your body is less able to respond to stress, and the mechanisms over-stimulated in the initial alarm phase by the involved hormones become resistant to more stimulation. In this let down phase you feel more tired and listlessness, and have a desire to rest. This is a natural after-effect following the over-expenditure of energy during the alarm reaction.

After the recovery phase, if there is additional stress or a series of stressors, your body goes into another phase known as “the phase of resistance.” This phase of resistance can last months or even up to 15-20 years. If there is no decrease in the amount of stress, or if there are suddenly new stresses, your body can go into the phase of exhaustion. Some people never experience the exhaustion phase; others visit it several times in their life.

Entering the phase of resistance reaction lets your body keep fighting a stressor long after the effects of the fight-or-flight response have worn off. The adrenal hormone cortisol is largely responsible for this stage. It stimulates the conversion of proteins, fats and carbohydrates to energy through a process called gluconeogenesis (gluco=glucose, neo=new, genesis=making or origin) so that your body has a large supply of energy long after glucose stores in the liver and muscles have been exhausted. Cortisol also promotes the retention of sodium to keep your blood pressure elevated and your heart contracting strongly.

The resistance reaction provides you with the necessary energy and circulatory changes you need to deal effectively with stress, so that you can cope with the emotional crisis, perform strenuous tasks and fight infection. Dr. Selye and subsequent researchers produced this GAS pattern over and over, resulting in hemorrhaged adrenal glands, atrophied thymus glands (the chief gland in immunity), and biochemically devastated bodies of animals exposed to repeated stress. The adrenals were the pivotal glands in the countless experiments involving stress.

If arousal continues, your adrenal glands will continue to manufacture cortisol. Cortisol is a powerful anti-inflammatory hormone that, in small quantities, speeds tissue repair, but in larger quantities depresses your body’s immune defense system. A prolonged resistance reaction increases the risk of significant disease (including high blood pressure, diabetes, and cancer) because the continual presence of elevated levels of cortisol over-stimulates the individual cells and they begin to break down. Your body goes on trying to adapt under increasing strain and pressure. Eventually, if this phase goes on too long your body systems weaken in the final stage of the general adaptation syndrome, exhaustion. The resistance reaction phase can continue for years. But because each of us has a different physiology and life experience, the amount of time we can continue in the resistance reaction phase is unpredictable.

In the exhaustion stage, there may be a total collapse of body function, or a collapse of specific organs or systems. Two major causes of exhaustion are loss of sodium ions (decreased aldosterone) and depletion of adrenal glucocorticoid hormones such as cortisol. In the resistance phase, with its increased levels of cortisol, there is also an increase in the level of aldosterone because both are stimulated during a normal response to stress. This keeps sodium high in the circulating blood and potassium low because it is excreted into the urine during times of high cortisol/aldosterone. However, the exhaustion phase can often begin so quickly that these electrolytes (sodium and potassium) are caught in the lurch. During this phase, lower levels of cortisol and aldosterone are secreted, leading to decreased gluconeogenesis, rapid hypoglycemia, sodium loss and potassium retention (for more detail, see the previous section on aldosterone “Adrenal fatigue and the craving for salt.”) Body cells function less effectively in this condition as they rely heavily on a proper amount of blood glucose and the ratio of sodium to potassium. As a result, your body becomes weak. This means that during the exhaustion phase your body lacks the very things that would make you feel good and able to perform well.

When adrenal corticosteroid hormones are depleted, blood sugar levels drop because low cortisol levels lead to lower levels of gluconeogenesis. This means that your body is less able to produce its own blood glucose from stored fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, leaving you more dependent on food intake. Simultaneously, insulin levels are still high. The combination of low cortisol and high insulin levels leads to a slowing of glucose production and a speeding of glucose absorption into the cells. Hypoglycemia results because the body cells do not get the glucose and other nutrients they require. When energy is not available, every energyrequiring mechanism of the cell slows dramatically. This lack of energy combined with the electrolyte imbalance produces a cell in crisis. When energy and electrolytes once again become available and the cellular stress decreases, the damaged cell must be repaired or replaced. The reactivation of normal cell functions is an energy consuming series of events that uses up a greater amount of energy than is normally required. Yet this has to take place in a situation in which your body is struggling just to produce enough energy to maintain some semblance of homeostasis.

Uninterrupted, excessive stress eventually exhausts your adrenal glands. They become unable to produce adequate cortisol or aldosterone. This combined effect on your kidneys of too little aldosterone, leads to collapse, and can even result in death in extreme cases.

Humans, although displaying many of the same physiological responses to stress, have their own unique pattern of adaptation and maladaptation. The next section is about how we respond to the various stresses of life.

The general adaptation syndrome (GAS) described in the previous section is the model developed by Hans Selye to explain how animals adapt to stress. It is the paradigm commonly used to represent the generic physiological reaction to stress. In this model, the initial reaction that produces a large rise in cortisol is followed by a period of recovery in which the cortisol is low. As the stress is continued, the animal adapts to handle this stress and so produces higher levels of cortisol. This is called the phase of resistance. If the stress continues, eventually the adrenals give out and the animal plunges into the stage of exhaustion, unable to respond to stress. The GAS is an animal model that has many human variations. Humans however, being an odd kind of animal, do not necessarily respond in the same ways that laboratory animals do. In fact, humans have several additional patterns of responses to stress which vary in complexity and timing. The descriptions given below are brief snapshots of the most common patterns of adrenal fatigue I have seen clinically over the past twenty-four years. Any practicing physician who is aware of these patterns will notice them frequently in his practice. However, it is important to realize that each person suffering from adrenal fatigue has his or her own variation of the patterns of adrenal fatigue. Therefore individual profiles may not fit exactly any of the ones described below. The numbering is only for convenience sake and does not indicate the severity or importance. Despite the variety of forms adrenal fatigue can take individually, the Questionnaire and the other tools in this book are reliable ways of detecting its presence, no matter the individual pattern.

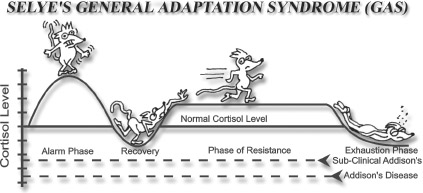

Pattern #1 - A long phase of resistance followed by

adrenal fatigue

The first pattern is what is popularly referred to as the “iron man/woman.” These are people who nothing seems to bother. They maintain a resistance stage most of their lives, being able to handle anything that life throws at them. Although stressors may get them down for a day or two, possibly even a week, they predictably bounce back as good as new. Usually these people remain in a resistance stage until late in life when old age diminishes their adrenal function. In some cases however, a major stressor, such as a very severe injury or emotional upset, precipitates adrenal fatigue. Sometimes they are still able to climb out and recover and will continue through life with ability to handle stress (see illustration “Human Response Pattern #1”). Clinically, these people would appear to have lost some of their previous ability to handle stress following a major life event (accident, illness, highly emotional situation, etc.). An example of this pattern is the guy who can handle anything at work, nothing ever bothers him. He takes on larger work loads and does whatever is demanded of him with no problem. Then one day an extremely stressful event occurs in his life, such as a major illness, surgery, or a marital break-up, and after that he seems much less able to handle the stresses of his job. Even after a time of recovery, he continues to work but is never the same person. If his salivary cortisol levels were checked carefully, they would probably be mildly elevated at first, but after the event, they would be mildly suppressed. If he took the questionnaire in this book he would show many of the indications of hypoadrenia or adrenal fatigue. However he probably started out in life with strong adrenals, otherwise he could not have endured stresses that his fellow workers were not up to. Chances are he did not experience the increased responsibilities or added work assignments he took on as stressors, but rather gladly accepted or even welcomed them. However, his added responsibilities were his undoing. This is a very common pattern. These people usually have an excellent chance of recovery, but must avoid the temptation to live on a constant “adrenal high”-the rush of continually pushing themselves to the brink, or to take on excessive responsibilities. If they continually push themselves, they can develop a pattern like the last part of this one or like #3. These are people born with strong adrenals and they are becoming more rare.

Suede was the top man in flight school. He was always the calm one, who remained even and good-natured no matter what challenges the flight instructor threw at him. He elected to be a tail gunner and was the best there was in any training school during World War II. No matter how much responsibility he was given, Suede could always be counted on. When he was assigned to a particular bomber, all his crew were happy to have him and considered him one of the strongest assets to their crew. During their first mission, they encountered unusually heavy anti-aircraft and enemy plane attacks. Suede was put on the spot almost immediately as the rear tail gunner. After suffering damage from gun fire to the rear of the plane, the Captain asked Suede if he was all right. Not getting any answer, he sent the radio operator back to check on him, fearing he might have been injured in the air battle. When the radio operator found Suede, he had both hands on the gun, starring straight ahead, frozen in one position. They had to pry his hand away from the gun and manually remove him from his perch. Once back on the ground, Suede was taken to the hospital and then to a recovery unit where he slept most of the day and could barely manage to dress or feed himself for several weeks. He was never to fly again.

This is a classic Pattern #1 response of adrenal overload and breakdown.

Reverend Little was a kind and caring man. He had been the pastor of his congregation for several years. Because it was a small church and unable to afford a full-time pastor, Reverend Little had a couple of side businesses in a larger town nearby to supplement his meager income. He worked most nights when there wasn’t any choir practice, prayer meeting or sermon to prepare. The number of his side jobs kept growing, as did his congregation. One night, Reverend Little went to sleep as usual, but the following morning he was unable to get out of bed. He had no fever, nausea or vomiting. He had no signs and symptoms of any typical illness. He just couldn’t get out of bed. In fact, he lay there for three weeks before he was finally able to get up and return to work. After that he closed all but one of his businesses and shared the ministry with his oldest son. Reverend Little was never diagnosed with any ailment. He continued to operate on about one-quarter of the energy he had known, but he was able to manage by setting his sights lower and getting help from his family.

This is a classic example of a man who experienced a pattern #1 adrenal fatigue, yet never knew it and made the best adaptation he was able to make. Had his symptoms been diagnosed and treated, or better yet, had he seen that his lifestyle was placing him in jeopardy, he could have avoided much of what he suffered after his collapse. He could have remained extremely active, but in a more balanced way and thus avoided the period of debilitation caused by adrenal fatigue.

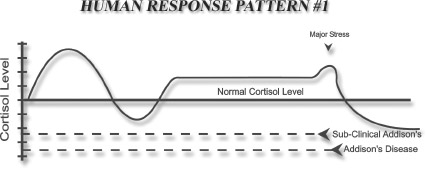

Pattern #2 – A single stressor followed by adrenal

fatigue

There is a type of adrenal fatigue that can occur in people after only one stressful event. This pattern is similar to the first except there is no long phase of resistance. There is the typical alarm reaction and recovery phase, but only partial recovery is seen. These people never totally rebound from the recovery phase. Instead of progressing to the resistance phase, their cortisol levels remain below average, but at a level just high enough to allow them to function sub-marginally, with many of the symptoms of adrenal fatigue (see illustration “Human Response Pattern #2”).

This pattern is turning up more frequently as more children are being born with weak adrenals and their diet does not provide enough of the nutrients needed to strengthen and rebuild their adrenals. Because the adrenal glands in these people do not have the resiliency to rebound after a severe stress, they have to function at a lower level with decreased adrenal output (as evidenced by the low cortisol levels). These people can recover, but they need to use the program in this book to do so, as well as avoid situations that constantly stress them. Rest and a calm, non-stressful lifestyle is essential if they are to be at their best.

Mrs. Ollert was a happy middle aged woman. Like most women, she was a dedicated mother and although divorced from her husband, had a good relationship with her 14-year old son, Robert. She had Robert later in life, when she was 35 and he was her pride and joy. One afternoon Robert and a friend of his were working out in the workshop on a science project. However, their curiosity had carried them way beyond the confines of their project. The two were constructing a homemade bomb when it exploded, killing both of them. Suprisingly, Mrs. Ollert took the news rather stoically. Even as saddened and disheartened as she was, she kept a cheerful front and carried on with life. On the anniversary of Robert’s death, she decided to force herself to clean his room. When she got to his closet to clean out his clothes, something snapped. I saw Mrs. Ollert two days later. When no one came to the door and her car was still in the driveway, the neighbor became suspicious. Peeking through the windows, she could see Mrs. Ollert sitting in the living room with a box of chocolates open in front of her on the coffee table. Mrs. Ollert seemed to be awake, but did not respond to the knocks on the door or the yelling from the window. When I got there, she showed the same lack of response to my voice so we forced entry into the house. When I examined her, I found she was in a state of shock and fatigue and was quite dehydrated. After a brief hospital stay, during which her electrolytes were replenished and she was given intravenous nourishment, she became more conscious. At that point she broke down and sobbed for a long time as she experienced the sudden and severe emotional shock of confronting her son’s death after hiding it from herself for a year. Her adrenals basically gave out temporarily. She was unable to care for herself. The only thing she could do was to sit on the couch and stare, eating an occasional chocolate. The chocolates, although giving her a temporary bit of energy, only worsened her low adrenal related hypoglycemia. Had care not intervened, she could likely have passed away. With a strong program of herbal, nutritional and other support, including counseling, Mrs. Ollert recovered. Nothing can replace the loss of a son, nor negate the traumatic shock of losing him so suddenly, but with time and care she was able to overcome the shock and grief enough to go on and live a good, normal life. She was careful to avoid unnecessary stress and regularly refresh herself.

This is an example of how one severe shock was enough to cause the adrenals to almost shut down. In pattern #2 adrenal fatigue, one intense episode of stress over-burdens already weak or strained adrenals causing a serious reduction in adrenal function. It can take many months or even years for these people to recuperate from such an event and, without proper treatment, many never regain normal adrenal function.

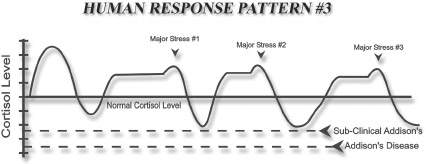

Pattern #3 – Repeated partial recovery followed by re-

curring adrenal fatigue

A third fairly common pattern of adrenal fatigue occurs when people experience a series of stressful events over time that keeps their adrenals continually over functioning until, finally, at some point in their lives their adrenals become fatigued and they do not rally. They go through repeated cycles of resistance and exhaustion after an initial shock or alarm reaction but each time they are able to return to a stage of resistance and function with above normal levels of cortisol. These people can carry on in a stage of resistance for several years until another major stressor or a series of stressors overwhelms them, after which there is another usually longer recovery phase that once again elevates them to the stage of resistance. The larger the stress, the longer the recovery. However in many of these patients, often in mid-life, there is a major stressor, after which they do not return to the high cortisol levels of the resistance stage but rather remain at the low cortisol levels of adrenal fatigue. This is illustrated in “Human Response Pattern #3.”

The people who follow this pattern usually have relatively strong adrenals but are unable or unwilling to change their continual encounters with stressful situations. Over time life beats them down, leaving them much less able to endure stresses that they previously would have handled with ease. These can be very willful individuals who refuse to change or they can also simply be people who unavoidably experience an unfortunate series of circumstances in life. It is possible for them to fully recover if they modify the problem areas in their life situation and follow the program in this book.

Perry was a gifted doctor. His understanding of physiology and pathology were beyond all of his peers. Perry was a person who needed to understand the entire picture. He could not rest until his understanding was complete. When he took a practice left by a retiring doctor in the woods of the North Country. Perry found that by using advanced nutritional techniques he could eliminate the rampant alcoholism prevalent in the community he served. When he tried to share how intravenous injections of Vitamin B and C complexes, consistently took away the compulsion to drink in his patients, none of his peers were interested and branded him a maverick. Eventually, one of his very ill patients died under his care. The medical board took the opportunity to penalize him for his progressive practices. After a kangaroo court inquiry, they found him guilty of medical malpractice and removed his license to practice medicine for life. The only other person given this harsh treatment was a serial killer Medical boards usually punish misconduct with a brief license suspension, a required remedial course or other such temporary measures. A 1-2 year suspension would have been a strong reprimand. Perry collapsed under the strain of their decision. However, with time and his understanding of physiology and nutrition, he was able to recover and was awarded a license by another health profession. Soon overburdened by patients due to his extraordinary approach, Perry began to buckle under the strain of treating very ill patients. He was a giver and he continually exhausted himself treating his patients. Luckily for him, Perry had a good ability to recover and could bounce back with rest and proper nutrition. However, when he was seeing patients, Perry did not incorporate rest or rejuvenating aspects into his lifestyle, and so he repeated the cycle of exhaustion and recovery until he closed his practice. It was only when he retired that Perry was able to recover and maintain his recovery. Perry is an excellent example of pattern #3 type of responses to stress.

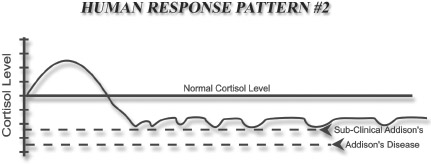

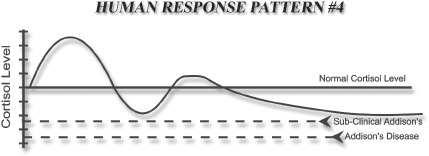

Pattern #4 - Gradual decline into adrenal fatigue

This is a pattern of gradually decreasing resistance to stress (see illustration “Human Response Pattern #4). The people who exhibit this pattern experience many stresses over time but with each event their level of recovery diminishes. They are less and less able to return to high or even normal cortisol levels until, finally, their adrenals become so fatigued that they cannot handle anything more stressful than an uneventful routine day. Their cortisol levels may start out higher than normal but gradually drop below normal and then remain low, unless a concerted effort is made to help their adrenals recover. These people also can recover if they follow the program in this book, but it takes time and dedication.

Michelle was a truly good woman, the kind you would like to have living next door. A mother of 5 who believed in trying to provide her children with everything, she was the dedicated mom other women admired. As time went on, Michelle found herself lacking the energy she needed to give her children what she thought they needed. Five is a lot to take to music lessons, sports, play practices and birthday parties in between cooking, cleaning and the never ending demands of being a mom. Being on a low income, Michelle also suffered the stresses of trying to make ends meet and having to do things herself because they lacked the finances to hire someone to do or buy what she needed. Gradually, Michelle’s spring wound down. Over time, she gradually slipped into a severe state of adrenal fatigue. When she first took my questionnaire she asked me, “How could you have been peeking in my windows when you didn’t even know me? Answering your questionnaire was like seeing the story of my life.” Seeing how her perfectionistic nature, religious convictions, and putting everyone else’s needs first had driven her to adrenal exhaustion, Michelle was able to release her unreal expectations, let her children assume most of the household duties and develop a lifestyle that was both responsible and rewarding. Together with improved nutrition and dietary supplements, Michelle has entered into the best phase of her life.

Michelle is a good example of pattern #4. Without the change she implemented after seeing her state of adrenal health, recovery would not have been possible. This is a frequent pattern seen in strong willed perfectionistic people who constantly subjugate their own needs to “do their duty.” It may be work, family or social demands that drive them, but the result is often the same. This is also a frequent pattern seen in single parents or in people who refuse to ask for help, trying to do it all themselves. Changing their physiology to recovery from adrenal fatigue is usually not the challenge. The challenge comes with changing the attitudes and beliefs that have driven them to adrenal fatigue.

Patty was a bright and athletic thirteen-year-old. She had all the right qualities to be a success in her present life and in her future. An accomplished soccer player, she was making top marks in school and enjoyed being one of the most popular students. Life was looking good for her. Then one day her soccer coach announced out of the blue that he was leaving the team. They were unable to find anyone else to replace him. There would be no more competitive soccer for her and her teammates. She was crushed because soccer had been her life; she had been practicing 25 hours per week, year round, for years and was hoping for a soccer scholarship to university. There was no other equivalent team for her to train with in town so Patty’s world was suddenly turned upside down.

She went through a period of grief and depression that lasted over two years. In the middle of this difficult time she started attending a high school for the gifted and talented that required 3-5 hours of homework nightly. By the middle of the first term she was frequently getting sick and it was taking her longer to get over these bouts of flu and respiratory infections than normal. At the end of the first year she was asked to leave the school because her grades had fallen to unacceptable levels. But she appealed and was allowed to continue on probation for another year. Her sophomore year produced better marks, but the extreme stress of the previous two years had driven her into adrenal fatigue with many of the symptoms of hypoglycemia. This produced almost uncontrollable cravings for the quick energy of refined carbohydrates and resulted in unwanted weight gain.

Even though her Adrenal Questionnaire test score was extremely high, she initially resisted making any meaningful lifestyle changes, especially resting more and eating better. She continued at a school that pushed their students to the brink. The second year had nearly twice the homework as the first year, but she was unwilling to change schools, lessen her social life or do anything substantive about her hypoadrenia. Instead she continued to snack her way through life eating only occasional breakfasts, no lunches, grabbing something from the refrigerator after school, refusing to eat supper with her family on most occasions and keeping herself going with carbohydrate snacks late into the night. With her hypoadrenia also came problems sleeping, so she often was not able to go to sleep easily. On the surface she appeared to others to be managing well, still popular and active, but underneath, her health was being eroded by her insistence on pushing herself and refusal to change.

Patty was a person designing herself for pattern #4 hypoadrenia. Luckily, her youth and intelligence helped her recover and eventually have a life that was more enjoyable and less self demanding.