It is easy to assume a wine’s quality is directly correlated to its price. Generally, folks trust that each incremental dollar spent gets a more exciting and delicious wine. While it is true that most esteemed wines are costly—because they are expensive to produce and also sometimes scarce—just because a wine is expensive does not mean it is better.

There’s an inner-industry assertion that all superpremium wines (those that retail at one hundred dollars or more per bottle) cost about ten dollars a bottle to produce, and anything a winery charges above that is pure profit. Do I agree with this sweeping generalization? Not totally. There are so many factors that go into pricing a wine that a “typical profit” is impossible to deliver. For example, some wineries may own their properties outright, bringing the cost to produce wine down drastically. Some may owe millions, and thus need to charge more to recoup their investments.

There is some truth to the smoke-and-mirrors pricing theory though. Given the right set of circumstances, wine prices are sometimes falsely inflated. For example, a cabernet blend that just won’t sell at thirty-five dollars a bottle is jacked up to seventy-five because the brand manager believes it will sell better if it is perceived as a more costly and thus exclusive wine. The wine and the packaging remain the same, and the wine actually does sell better at the higher price point. Is it a “better” bottle because the price changed? Not a chance. This is unfortunately all too common.

Conversely, sometimes bottles are subjectively great because they overdeliver for the price. I can appreciate an expensive, legendary wine any day. But a “better” bottle, for me, is finding something I love that I can afford to buy on a regular basis. More wine = happier Melanie.

Screw caps rock. I’m a big fan. The reason? There are many things that can cause a bottle of wine to go bad. Too much heat, too much light, bacteria, chemicals, and simply old age can turn the best wines downright rotten. The thing that goes wrong most often is that the wine is “corked.” A corked wine has been contaminated with Trichloroanisole, or TCA, a funky, musty compound. TCA contamination, interestingly a by-product of the bleaching process most wineries undertake to keep things clean, is one of the biggest problems in wine, affecting as many as one in every twelve bottles.

Corked wine exists on a spectrum. Sometimes it’s overt, and that insidious, musty, wet cardboard smell is pervasive. Other times it is much more discreet, and wine pros debate its presence. However apparent, it won’t make you sick, but the wine certainly won’t taste the way the winemaker intended. (All that mustiness mutes fruit, leaving the wine tasting dirty and flat.) The worst part is that most wine drinkers have never even heard of TCA. They drink a wine that tastes musty, or maybe just “off,” and make a mental note not to buy that wine again. How sad.

The solution? There are a number of enclosures that eliminate the possibility of TCA cork contamination. Zorks, glass tops, synthetic or plastic stoppers (unfortunately hard to open), and screw caps are all promising options. You’ll find the majority of these alternative enclosures on wine from the industry’s youngest and most innovative regions, like New Zealand. The real reason why most wineries don’t switch to cork alternatives and fix the problem of TCA right now is perception—they think you’ll think their wine is cheap.

Now, to be fair, there is some validity to the argument that the teeny-tiny amount of oxygen exchange that happens with natural cork plays an important role in the evolution of fine wine over decades—decades! But most people are drinking the wine they buy today, today. So for all but the most enduring wines, this argument is moot.

There are plenty of people who lament the potential loss of the tradition, romance, or pop of a true cork. However, I can assure you there is nothing romantic about a corked bottle of wine. My advice? Screw corks whenever possible; buy wines with screw caps.

Sulfur, a natural chemical element, has been used to preserve wine for centuries. Sulfur dioxide, the most common form of sulfur used in winemaking, inhibits yeasts and acts as an antioxidant, keeping the wine fresh in the barrel and bottle. Chances are, you are not allergic to it. Only about 1 percent of the population—typically severe asthmatics—are truly allergic to sulfites, which is why the Food and Drug Administration requires wineries to print “contains sulfites” on their labels. If you were allergic to sulfites, you’d be on a heavily restricted diet. Many processed foods contain much higher levels of sulfites than wines do. Some of the things you wouldn’t be able to eat include dried fruits, fruit toppings, shrimp, corn syrup, pickles and relish, maple syrup, avocado dip and guacamole, and many fruit juices and soft drinks.

So if you’re not allergic to sulfites, why do you get:

Big, hearty red wines have a lot of alcohol. There’s always the chance that you drank too much wine and didn’t eat enough food or drink enough water and you have a good old-fashioned hangover. Another probability is that you could have sensitivity to tannin, in which case you should try drinking white wines. If you’re a red-only lover, switch to lighter red wines, like pinot noir, which have less tannin.

Some light red wines to try if you suspect you’re sensitive to tannin:

pinot noir: a light and silky red with aromas of earth, raspberry, and cranberry

Beaujolais: a juicy, light French wine made from the gamay grape

barbera: a fruity and refreshing (but still rustic and earthy) Northern Italian red

According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, some people, especially those of Eastern Asian descent, are genetically predisposed to this reaction.

If you’re not East Asian, and you find yourself with a stuffy nose or covered in itchy red blotches when you drink some wines, you may be allergic to (A.) the histamines that are a natural by-product of fermented beverages; (B.) the histamines that live inside the grapes themselves; or (C.) other environmental allergens (like dust and mold) that are carried on the skins of the grapes. In any case, there’s no way to know which particular wines will trigger your allergy. Until we fully understand the science of allergies, you are in for hit-or-miss drinking.

Did You Know? Red wines contain fewer sulfites than white wines. Tannin, most present in reds, is a preservative, and makes sulfur dioxide use less necessary.

A blend is a wine made from a mix of grapes, as opposed to a single-varietal wine, which is made from only one. (Well, theoretically one; different regions have different rules, but with most single-varietal wines, anywhere from 75 to 100 percent consists of that one grape.) For some reason, many new wine drinkers feel drawn to conclude that one is distinctly better than the other. Let me tell you, in no uncertain terms, that you don’t have to, nor should you, declare a winner in this fictitious contest. Some blended wine is better than wine made from a single grape. Some single-varietal wines are superior to blends. There are many factors that go into evaluating if a wine is good or not—most important, do you like the way it tastes? The sheer nature of a wine’s blended or non-blended status should not influence your feelings in the slightest.

So why blend? Sometimes winemakers blend two grapes together because they complement each other (e.g., Winemaker Sam’s cabernet is particularly bitter and tannic, so he balances it by blending in some soft, fruity merlot). Sometimes blending is used to compensate for farming challenges. A notable example of this kind of blending happens in the Bordeaux region of France. The weather there stinks. Rains at harvest are probable and can be devastating. As an insurance policy, Bordeaux winemakers have traditionally used up to five different grapes in the blend. All five grapes ripen at different times. If the rain destroys one grape’s harvest, they can make up the difference with the other four.

Blending can help compensate for short-comings, adding complexity and depth to the flavor of the wine, if done in the right way. Blending can also go awry, and a wine can end up tasting like soup: a homogeneous mix in which nothing distinctive stands out. To blend or not to blend—there’s no right answer. You’re just going to have to enjoy them both.

“Legs,” or “tears,” are the drips that you see running down the inside wall of your wineglass after you swirl a wine. The first wine lie I remember digesting was that thick legs were the sign of a good wine. I can just hear my know-it-all uncle’s voice: “Oh yeah, when you see big legs like that, it means the wine is top-notch.” I, of course, believed him—until I learned otherwise. In truth, thick drips are not an indication of quality. But don’t take your investigative goggles off just yet; they do give clues about the wine.

If drips are thick and slow-moving, you can be assured the wine you’re about to consume is heavy in alcohol and body. The texture will be thick in your mouth (like whole milk or cream). The wine will likely taste full and very rich. If it’s hard to see any drips, you’ve got a wine that is light in body (like skim milk). It will taste thinner and have less alcohol. The flavors will likely be more delicate and fine.

If you dig a substantial, heavy wine, then voluptuous legs in your glass are an indicator that your mouth is about to get happy. If you like a more delicate wine, that might not be the case. Ah, yet another totally subjective wine debate. Are you sensing a trend here?

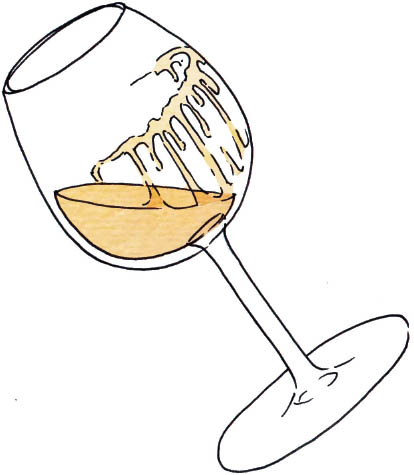

We often hear the C-word, Champagne, used universally to talk about any sparkling wine, but that’s a mistake. Here’s the skinny: sparkling wine is an umbrella term meaning any wine with bubbles made anywhere in the world. Champagne is a type of sparkling wine. It just so happens to be the original and most iconic type of all.

SPARKLING WINE HAS MANY NAMES . . .

I love bubbles. Whether it’s the hiss and pop of all that pent-up pressure, the delicate strand of pearl-shaped air dancing in the glass, or the signature sophisticated tang, there’s just something different—something sexy—about wine with sparkle. There’s no denying that a glass of great Champagne will magically make you stand straighter, speak more eloquently, and smile more often. This curious behavior is likely due to all the cachet attached to Champagne, the world’s most expensive, extravagant sparkling wine.

What makes Champagne so special? True Champagne comes only from Champagne, France. Champagne is one of the coldest and most northerly winegrowing regions on the planet. In fact, the only reason grapes can survive the chilly temperatures (and constant threat of frost) is that there’s usually ample sunshine during the growing season thanks to the northern latitude. (I say usually, because sometimes there isn’t, in which case entire vintages can be ruined.) Grapes that are able to straddle this fringe climate retain a laser-like acidity that ultimately creates intensely focused, precise wines. When the weather is perfect, this is the best place on the planet to grow the grapes destined for sparkling wine.

The dirt here is special too. Apparently, the Champagne region used to be underwater, and the subsoil is rich with marine fossils. What this means is that the best wines from the area take on a chalky, minerally aspect that you can actually taste in the wines.

In addition to the unique attributes of the grapes, climate, and soil, Champagne (the sparkling wine) abides by strict laws that govern how it is made (the most labor-intensive process possible) and how long it is aged before it is released (longer than any other sparkling wine, which gives it complexity and depth). The most important process, and the primary distinction between how Champagne and other types of sparkling wine are made, is that the secondary fermentation (the process by which bubbles are born) happens in the bottle, as opposed to another, larger vessel.

Champagne’s glamour is undeniable, and that has proven an irresistibly shiny target for imposters. In Europe, there are laws in place that protect the name Champagne. No other producers in the European Union can make sparkling wine and label it Champagne. Making wine in Spain and labeling it with a French region would be as preposterous as calling a bottle from France “Napa.” However, outside the European Union, anyone, unfortunately, can steal the name. This is why you sometimes see “Australian Champagne” or “California Champagne” printed on a wine label.

It is worth noting that typically only subpar wineries do this in an effort to cash in on the reputation of the most famous and high-quality sparkling wine. Well-respected producers wouldn’t think of using the C-word illegitimately. They know that although they will never be able to produce Champagne, they can still make a gorgeous sparkling wine. They don’t need to borrow a name to get your attention.

Did You Know? More than 25 percent of all sparkling wine is sold during the two weeks before Christmas. /Oakland Tribune

Easier to Find

Billecart-Salmon

Billecart-Salmon Bollinger

Bollinger Deutz

Deutz Krug

Krug Laurent-Perrier

Laurent-Perrier Philipponnat

Philipponnat Roederer

Roederer Taittinger

TaittingerHarder to Find

Egly-Ouriet

Egly-Ouriet Gaston Chiquet

Gaston Chiquet Henri Billiot

Henri Billiot Jacques Selosse

Jacques Selosse Michel Turgy

Michel Turgy Pierre Peters

Pierre PetersCalifornia Sparkling Wines

Many parts of the Golden State are just too warm to grow grapes destined for sparkling wines. A few very-cool-climate regions, however, are perfect, especially for wines from these producers.

Iron Horse Vineyards

Iron Horse Vineyards Roederer Estate

Roederer Estate Schramsberg Vineyards

Schramsberg VineyardsCava

When it comes to bang-for-your-buck bubbles, it doesn’t get much better than cava, Spain’s sparkling wine. Dry, citrusy cava is cheap and cheerful, simple and straightforward, and should be paired with equally laid-back foods. The following are some of my favorites.

Avinyo brut reserva

Avinyo brut reserva Jaume Serra Cristalino

Jaume Serra Cristalino Castillo Perelada

Castillo Perelada Raventós i Blanc

Raventós i BlancMost prosecco, which hails exclusively from several regions in northern Italy, is light, frothy, and much fruitier than Champagne. Less pressure in the bottle translates into less aggressive bubbles, making prosecco dangerously easy to drink. (The average price tag of around fifteen dollars a bottle doesn’t hurt either.) Try bottles from the following producers.

La Marca

La Marca Nino Franco

Nino Franco Zardetto

ZardettoMoscato d’Asti

There is perhaps no more aromatic sparkler than moscato d’Asti, the famously sweet and floral wine from Piedmont, Italy. Moscato d’Asti is sweet enough to pair with light desserts, and comes alive when paired with berries, citrus, and stone fruits. Below are some recommended bottlings.

Ceretto S. Stefano

Ceretto S. Stefano Saracco

SaraccoSparkling Shiraz

Not only does this wine’s appearance spark conversation (a dark purple wine with bubbles!) but its myriad interesting flavors will have your guests talking too. The best have a strange yet beautiful bouquet of cranberries, pomegranate, chocolate, and smoke. Sample the wines listed below for a taste of this unusual sparkler.

Molly Dooker

Molly Dooker The Chook

The Chook

This is a book about uncovering truth, so I’ll admit it: The first wine I ever drank was Boone’s Farm Strawberry Hill. It was pink and sweet and I distinctly remember an awful hangover. I bet many of you reading this may have a similar memory of your first experience with wine. Consequently, when most people think pink, this is what is etched in their mind—syrupy sweet wines like Boone’s Farm, “blush” wines in a jug, or the slightly more respectable white zinfandels of California. Although these saccharine beverages are technically wine and they serve as a sort of gateway substance to the more genuine stuff, the truth is that they taste more like a Jolly Rancher than real, grown-up wine. However, as you may have gleaned by the ironic heading “Pink Is Passé,” serious pink wine exists. And if you’re turning up your nose to all wines with a rosy hue, you are missing out.

Dry pink wines are collectively called rosé (ro-ZAY). They are made all over the globe, but most notably stand out in southern France and Spain. Rosés can be made from a variety of grapes, most often grenache, syrah, mourvèdre, cabernet franc, and tempranillo (or a combination of any of these). They are made in a few different ways: (1) by blending red and white wines together, (2) by leaving the grape skins in brief contact with the juice before fermentation, or (3) by a technique called saignée, where not-quite-red-yet juice is “bled” off of red wine destined to continue its own fermentation.

Good rosé can be delectable in a way no other wine can; it can be simultaneously juicy and tart, robust and delicate. They are best drunk very fresh and young (don’t buy last year’s vintage on clearance) and are best served well chilled, outside, in warm weather. Seriously. These are not winter wines. Rather, they are wines that exude the laid-back charm of a summer cookout or a day at the beach.

(1) blending red and white wines together

(2) leaving the grape skins in brief contact with the juice before fermentation

(3) a technique called saignée, where not-quite-red-yet juice is “bled” off of red wine destined to continue its own fermentation

Bonny Doon, Vin Gris de Cigare

Bonny Doon, Vin Gris de Cigare Château Pesquié Terrasses

Château Pesquié Terrasses Crios de Susana Balbo, rosé of malbec

Crios de Susana Balbo, rosé of malbec Domaine de la Mordorée “La Dame Rousse” rosé

Domaine de la Mordorée “La Dame Rousse” rosé Mulderbosch rosé of cabernet sauvignon

Mulderbosch rosé of cabernet sauvignon Parés Baltà, Ros de Pacs

Parés Baltà, Ros de Pacs Castello di Ama rosato

Castello di Ama rosato Domaine de Terrebrune rosé

Domaine de Terrebrune rosé Domaine Ott, Les Domaniers de Puits Mouret rosé

Domaine Ott, Les Domaniers de Puits Mouret rosé Domaine Tempier rosé

Domaine Tempier rosé

I can’t justly conclude a pink passage without at least mentioning the fabulousness of sparkling rosé. My desert-island wine, pink Champagne (and other rosé sparkling wines) can be powerful and profound, and extremely elegant at the same time. The following are some of my favorites.

Jaume Serra Cristalino brut rosé NV cava

Jaume Serra Cristalino brut rosé NV cava Gruet brut rosé NV

Gruet brut rosé NV Roederer Estate brut rosé NV

Roederer Estate brut rosé NV Lucien Albrecht Crémant d’Alsace brut rosé NV

Lucien Albrecht Crémant d’Alsace brut rosé NV Taltarni brut Taché

Taltarni brut Taché Schramsberg brut rosé NV/ Napa, California

Schramsberg brut rosé NV/ Napa, California Billecart-Salmon brut rosé NV/ Champagne, France

Billecart-Salmon brut rosé NV/ Champagne, France Egly-Ouriet Grand Cru brut rosé/ Champagne, France

Egly-Ouriet Grand Cru brut rosé/ Champagne, France