Temperature plays a substantial role in how a wine tastes. Serving a wine too cold can rob it of flavor; serving it too hot magnifies alcohol. The old adage of “red wines at room temperature” is actually faulty. It seems the advice is a holdover from about three hundred years ago, before the advent of central air, when the room temperature in dank, drafty England was much cooler. Generally speaking, red wines taste best at 60 to 65 degrees. If you don’t have a basement or wine fridge, I recommend popping your red wines in the fridge for twenty minutes or so before you drink them. A red wine served at today’s room temperature is bound to taste mostly of alcohol. White wines should be served a little cooler, at 50 to 55 degrees, and sparkling wines even colder, at about 45 degrees. Don’t worry about getting out a thermometer, though. Just try to remember the following.

sparkling wines: ice-cold

white wines, rosés, and dessert wines: fridge cold

red wines: slightly cool to the touch

If you’re seriously evaluating a flight of wines, it is best to taste them in an order—generally, lighter wines first, heavier wines last. This will ensure that your tongue doesn’t get coated with a big, hefty wine that desensitizes your taste buds and leaves them limp. If you’ve got a lineup that includes some special or older bottles, you might want to order the wines with the best or oldest bottles last. That being said, don’t stress over this. Mixing wine order is fine, too, especially when the ultimate goal is happy bellies.

Did You Know? Some people prefer light red wines slightly chilled. As an experiment, try your next bottle of Beaujolais, pinot noir, barbera, or Chianti slightly chilled (put it in the fridge for at least twenty minutes before you imbibe), and see if you agree that the descriptors “refreshing” and “crisp” are not exclusive to white wines.

1. Remove the foil cap. Use the blade on your corkscrew or a paring knife to cut the foil just below the glass lip. Alternatively, you can also just pull off the entire foil capsule with your hands.

2. Insert the wine opener (see “A Trusty Wine Opener,” page 15) and gently extract the cork.

Note: If you’ve got a wine with a screw cap, skip steps 1 and 2 and simply twist the top for the ahhh . . . snap of freshness.

1. Make sure it is well chilled. Too-warm wines will explode with froth when you pop the cork.

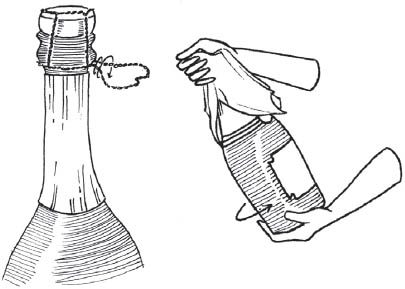

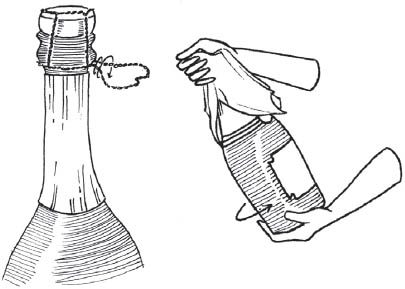

2. Remove the foil. Carefully untwist and loosen, but do not remove the wire cage. (It will help you keep your grip on the cork.) Make sure you keep your dominant thumb on the cork.

3. Keep a cloth napkin handy. While holding your thumb on the top of the cork—and pointing that cork away from anything or anyone—wrap the rest of your fingers on your dominant hand around the body of the cork and hold it in place with gentle pressure, as you twist the bottle with your other hand. You want the cork to emerge slowly and carefully. Contrary to popular belief, a loud pop is not desirable; the sign of a properly opened bottle is a gentle sigh. Pssssst. I love that sound.

Did You Know? The average bottle of Champagne contains ninety pounds of pent-up pressure. That’s why it is imperative that you not point the cork end at any person or fragile object while you’re opening. You could do some major damage.

Oxygen can be wine’s evil nemesis. But a little oxygen exposure when you first open a wine—especially a big, tannic wine—softens the wine’s hard edges and makes it palate-friendly faster. Using a decanter to aerate, or let the wine breathe, is a larger-scale version of swirling wine in your glass.

It’s a misbelief that simply opening a bottle and letting it sit on the counter is satisfactory to let a wine breathe. Only about a quarter-size surface area is exposed to oxygen when it sits in an open bottle. Instead, use a decanter or other wide-bottomed vessel you can easily pour out of again (a pitcher or vase will do) or pour small pours into wineglasses and start swirling.

Decanting wine might seem ostentatious, a relic of a more formal time, but there are several instances when it really comes in handy.

1. An Unruly Young Red

Young red wines with brawny tannins can really benefit from a few minutes of aeration. Oxygen smooths out the rough edges of the wine, making it taste softer and more seamless when it hits your mouth. Usually about thirty minutes does the trick.

2. A Dirty Old Wine

Over the course of many years, some wines, especially those that are unfiltered, create sediment—dark floating flakes of precipitated tannin and pigment. Although consuming it is harmless, you probably don’t want sediment in your glass because it tastes bitter and clouds up your wine. Grits are good; grit in your wine is not.

Separating wine from sediment is simple. Slowly, carefully, pour wine from the bottle into a decanter. Stop pouring when you start to see sediment, and toss those last few tablespoons of sediment-soaked wine out with the bottle.

3. Warming Up a Too-Cold Red

If a red wine seems a bit too chilly to drink, let it warm up in the decanter for a few minutes.

4. Foreplay

Like lighting candles and putting on just the right music, decanting can set the mood, and will typically invite veneration for a special bottle of vino.