The New Mainstream

The boundaries between alternative therapies and conventional medicine are blurring. Treatments once found only at the margins of health care are now being embraced in major hospitals.

Healing the Whole Cancer Patient

Comprehensive treatment programs now aim to not just save lives but also ease stress, relieve pain and promote a sense of well-being among patients

BY ALICE PARK AND AMANDA MACMILLAN

TUNNEL VISION CAN SET IN WITH A NEW CANCER diagnosis. Everyone–the doctor, the patient, the patient’s loved ones–focuses almost exclusively on treatment: the chemotherapy, surgery and radiation that aim to keep a patient alive for as long as possible. But now some forward-thinking doctors are realizing that a single-minded focus on treatment puts cancer, and not the person with it, at the core of the patient’s care. In an effort to change that, some hospitals across the country are launching innovative programs that aim not just to keep patients alive but also to keep them well.

“Medicine alone is not enough,” says Anne Coscarelli, founding director of the Simms/Mann University of California, Los Angeles, Center for Integrative Oncology, one of several cancer centers to adopt a comprehensive view of patient care. “For every physical effect of a cancer treatment, there is an equal psychological effect.”

Obvious as that seems, most cancer centers do not incorporate psychological care or social support into their patients’ treatment plans. That’s beginning to change, in part thanks to mounting research suggesting that a healthy mental state can play a part not only in quality-of-life improvements but also in a person’s prognosis. This emerging field, called psychosocial oncology, is about everything but the actual medical interventions.

Research shows that the mental toll of a new illness can drain a person’s physical resources and that social support can help patients cope with painful treatment regimens and improve recovery. A growing number of studies also show that social support, mindfulness meditation and exercise, among other holistic strategies, can reduce the depression that so often accompanies cancer while also improving people’s ability to complete their treatment plans without interruption.

That includes getting a good night’s sleep. Insomnia is a common concern for people who have cancer as well as cancer survivors, according to Jun Mao, chief of the integrative-medicine service at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) in New York. “Up to 60% of cancer survivors have some form of insomnia, but it is often underdiagnosed and undertreated.” A study led by MSK researchers showed that acupuncture and cognitive behavioral therapy were effective treatments to reduce insomnia.

Psychological distress, pain and fatigue are also very common in cancer patients, explains Mao, and should be more fully addressed in integrative care. The encouraging news is that there’s “a continually emerging body of literature that suggests many of the therapeutics we use, such as massage, acupuncture, meditation and yoga, have beneficial effects.”

Insomnia, psychological distress, pain and fatigue are common complications for cancer patients. The encouraging news is that a range of alternative therapies can help.

Integrative medical centers are also including patient resources on natural products. Such A-to-Z compendiums are far from blanket endorsements, however; in many cases, they are intended to offer patients information on which therapies have little or no evidence of efficacy, or even evidence that they are harmful. “Newly diagnosed cancer patients are undergoing much distress and anxiety,” writes MSK’s Gary Deng in an article in Current Oncology. “The public is exposed to an overwhelming amount of information and misinformation on CAM,” notes Deng, who is the medical director of integrative-medicine service, and it is vital that they “feel that they are not missing out on any options.” Deng adds that MSK’s online resource About Herbs, which is also available as a smartphone app, routinely receives more page views than MSK’s home pages, “underlining the tremendous demand for this kind of information from the general public.”

Such encyclopedic resources are also aimed at facilitating conversations between doctors and patients. About a third of cancer patients use alternative medicine, according to 2019 study published in JAMA Oncology. Out of more than 3,000 cancer patients who responded to questions about cancer and complementary therapy use through the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, just over 1,000 reported using one or more of these therapies during the prior year. Patients turn to alternative medicine for many reasons, including, according to the study, “persistent symptoms, psychological distress or to gain a sense of control over their care.” And some alternative therapies are indeed widely recommended by oncologists. Mind-body interventions like yoga, tai chi, meditation and mindfulness, which were each used by about 7% of patients, can keep people fit and energetic as they undergo treatment, reduce the side effects of traditional therapies, lessen stress and improve mental health. Cancer patients who were more likely to use complementary therapies, noted the study, were young, white and female.

But the problem, according to the study, was that about a third of these patients did not tell their doctors that they were using alternative therapies. Why not? In many cases, explained the survey respondents, either their doctors did not ask or they did not think their doctors needed to know. That’s a potentially risky oversight. Some herbal supplements may interact in unforeseen ways with conventional treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation. High levels of antioxidants can interfere with radiation, for example, and herbal supplements can become dangerous when mixed with certain prescription drugs. This is the reason, according to the study’s lead author, Nina Sanford, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, that it is paramount for cancer patients to discuss such use of supplements with their doctors.

The benefits of communication can also extend to side effects that are well known and seemingly unavoidable. Every year, for instance, tens of thousands of breast-cancer patients are prescribed aromatase inhibitors—medications recommended for up to 10 years to protect against a recurrence of the disease. But these drugs can produce side effects, including severe joint pain, which cause many women to stop taking them. Patients may now have another option they can discuss with doctors. Research presented at the 2017 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium suggests that acupuncture may reduce drug-related joint pain for such women and may provide a way for them to continue taking these potentially lifesaving medications.

“Aromatase inhibitors are one of the most common and most effective medications in breast cancer, and they’re used for both prevention and for early-stage treatment,” says lead author Dawn Hershman, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Columbia University and vice chair of the research network that conducted the study. “But we know that they don’t work if people don’t take them, and we know the most common reason people don’t take them is because they develop side effects.”

The cancer-fighting medicines are commonly prescribed to postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive breast cancers, sometimes for up to 10 years. (About 80% of all breast cancers are hormone-sensitive, also known as estrogen receptor–positive.) But about half of the women who take aromatase inhibitors report joint pain and stiffness that affect the knees, hips, hands and wrists. The pain can be so severe that it makes it difficult for women to walk, sit, climb stairs, type or drive a vehicle. Researchers even have a name for the condition: aromatase inhibitor–associated musculoskeletal syndrome, or AIMSS.

The study authors wanted to determine acupuncture’s potential as a non-pharmaceutical option for treating for the painful syndrome. “People don’t want to take a medication that causes its own side effects to treat the side effects of another medication,” says Hershman. “And in this country right now, we want to do everything we can to avoid prescribing opioids, especially on a long-term basis.”

Hershman and her colleagues enrolled 226 patients with early-stage breast cancer from 11 treatment centers across the country. The women who received acupuncture experienced at least a 50% reduction in pain after six weeks, and when the researchers followed up 12 weeks after the acupuncture treatments had stopped, the pain relief remained significant. Hershman believes the findings should give patients and doctors alike confidence that acupuncture may provide some benefit to women experiencing joint pain due to aromatase inhibitors.

Although breast cancer may be leading the way in the use of complementary medicine therapies, the larger goal for many practitioners is to broaden the use of such treatments to wherever they are determined to be appropriate. And toward this end, researchers as well as clinicians are increasingly paying attention to the subtler parts of the cancer experience, including how the disease can affect body image–something that is a major source of anxiety for many patients but often gets overlooked.

It is exactly this kind of thinking that encouraged the National Academy of Medicine, more than a decade ago, to advocate a more comprehensive cancer-treatment plan–one that includes stress-management strategies as well as emotional and financial support. “What doctors need to remember,” says Kathryn Ruddy, a specialist in cancer survivorship at the Mayo Clinic, “is that for the rest of their lives, these people may be dealing with the effects of our treatments. It’s our responsibility to support them the best way that we can.”

Doing that at scale will require a major shift that is still underway. For now, many of the largest and most comprehensive integrative-care programs exist thanks to philanthropic gifts. Leaders in the psychosocial-oncology field hope that such programs will one day be a line item on hospitals’ budgets in cities of all sizes across the country. “We are in a revolution where we are becoming more wellness-focused,” says Carolyn Katzin, an integrative-oncology specialist at UCLA. “But we are not there yet. We’re still in the middle of the shift.”

Clinicians are paying more attention to the subtler parts of the cancer experience.

Holistic approaches can often reduce the depression associated with cancer.

After Surgery: Supporting the Recovery Process

Hospitals are offering treatments that help relieve the physical, mental and emotional suffering that often accompanies major surgery

By Jeffrey Kluger

An operating room is a monument to the idea of not messing around. When you deliver yourself into the hands of semi-strangers and give them license—indeed, pay them money—to knock you out, open you up and manipulate your very innards, you want to know there is hard, tested science on your side.

That’s one reason complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has had such a rough time gaining purchase in most pre- and post-surgical wards. Even as more than 40% of Americans report receiving some kind of CAM treatment in any given year, the surgical arena has long been off limits. The problem is, surgery isn’t just about repairing or removing sick tissue—it’s about fear, pain, depression and stress, not to mention the deep existential terror that comes from walking into a hospital and knowing there’s a risk that you may not walk out again. That’s not the kind of thing that can be diagnosed with a CT scan or be repaired by microrobotic surgery. But it is exactly the kind of thing that can have a significant impact on healing.

And yet a wealth of research shows that what doctors call “psychosocial factors” and everyone else calls “feeling lousy and depressed” can have a powerful effect on how quickly surgical patients recover and how successful their surgery turns out to be. Studies like these have pushed leading medical institutions to look for new ways to aid recovery. More than a decade ago, the Mayo Clinic made one of the first big pushes into incorporating CAM into its pre- and post-op wards, targeting cardiac patients specifically. Few procedures are as grueling as heart surgery. For all the advances made in minimally invasive cardiac care, there’s just no other means to perform a bypass, for example, than by cutting the sternum, splitting the chest and subjecting the patient to hours of deep anesthesia while the heart is manipulated by hand, scalpel and suture.

All that awfulness makes feeling better—not to mention actually getting better—difficult. Mayo researchers thus decided to determine whether a bit of massage might help the healing process along. After recruiting a group of pre-op patients, the researchers assigned half to receive standard post-surgical care, including pain medications, plus two 20-minute sessions of massage on the second and fifth days after surgery. The other half received the same care, except that they spent those 20 minutes quietly relaxing with no massage.

Before and after the sessions, the patients evaluated their level of pain, anxiety and tension on a scale from 1 to 10. All the subjects in the Mayo study started out in more or less the same range in all three categories. But after just 20 minutes of hands-on attention, anxiety, pain and tension levels for the massage group plunged relative to the control group. Mayo researchers discovered similar results for audio therapy—simply listening to music or recorded nature sounds to reduce post-surgical pain and anxiety. Both represent further means to achieve the goal of reducing pain in order to hasten recovery.

Agonizing as pain can be, many patients coming out of surgery suffer even more from nausea. It’s a common side effect of general anesthesia that can be exacerbated by drugs or even the stress of being hospitalized. In a study in which acupuncture was administered shortly before surgery, Mayo researchers found that patients who received acupuncture reported feeling nauseous significantly less frequently than patients who did not receive acupuncture, and their suffering was significantly less acute when they did feel ill.

Similar benefits have been seen from other, equally nonmainstream treatments. Aromatherapy—with spearmint, peppermint, ginger or lavender oils—has been shown to ease post-op nausea. Reiki, a Japanese technique of energy healing, has reduced stress and sped recovery. Patients in the Mayo network are also offered meditation, yoga, tai chi and even animal therapy, in which companion dogs visit patients before and after surgery.

That number is likely to grow—and not just at Mayo. The uniquely violative, uniquely mortal nature of surgery makes it a feared and serious enterprise. But such gravity can open minds and clarify thinking too. Wisdom dictates not accepting just any old nostrum. Wisdom also dictates embracing ideas you might not ordinarily consider. When your health, welfare and life are on the line, you’re not likely to be picky about where legitimate help comes from. Relief and recovery are what count—and, more and more, CAM is delivering both.

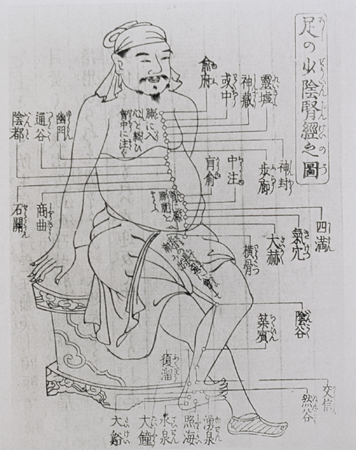

The Mystery of Acupuncture

Why it works is a matter of debate, but research shows that the ancient technique is effective for treating everything from menopause to backaches

BY JEFFREY KLUGER

THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE IS THE HISTORY OF preposterous ideas that turned out to be right. Illness couldn’t be caused by invisible creatures that invade the body. Then Antonie van Leeuwenhoek invented the microscope, and we discovered bacteria. Deliberately infecting people with an extremely mild case of a disease shouldn’t be the best way to protect them from catching a serious case of it. Then Edward Jenner hit upon smallpox immunization, and the era of the vaccine was born.

And you shouldn’t be able to treat all manner of afflictions, from headaches to backaches to depression to addiction, by letting someone stick needles into any number of 360 specific spots on your skin. Especially if the best explanation anyone can give you for why the treatment works is that it frees up the life force, or “qi,” that flows through the human body along 14 different lines, or “meridians.”

Yet the lure (some would say lore) of the ancient Chinese art of acupuncture is irresistible all the same, and not only in the Far East. The World Health Organization has declared acupuncture a useful adjunct for more than 50 medical conditions, including emotional woes like chronic stress. In the U.S., the National Institutes of Health agrees, endorsing acupuncture as a potentially useful treatment for addiction, migraines, menstrual cramps, abdominal pain, tennis elbow, nausea resulting from chemotherapy and more. NIH statistics from 2012 showed that 3.5 million American adults and 80,000 children had undergone acupuncture in the previous year. From 2002 to 2012, the number of adult users alone jumped by more than 1.5 million.

In 2009, the U.S. Air Force became a believer too, implementing battlefield acupuncture—a treatment that can include the implantation of semipermanent needles in key acupoints to block or disrupt pain signals—in Iraq and Afghanistan. Acupuncture is increasingly used by the military to deal with post-traumatic stress disorder as well. Now NATO forces are considering following the Americans’ lead. The Chinese military uses it routinely.

Civilian practitioners have embraced acupuncture in an even bigger way. Leading American hospitals like the Mayo Clinic and the Cleveland Clinic offer it as part of their alternative-care packages. And numerous groups, including the American Medical Association, have succeeded in getting a few states, including California, to designate acupuncture an “essential health benefit” under the Affordable Care Act. The move requires health insurers to include it on their list of covered services.

But just because a treatment is popular—even one that has been around for millennia—that doesn’t guarantee that it is effective. If it were, we’d long since have cleansed, Rolfed and low-carbed our way to immortality. More and more, though, acupuncture is getting the close empirical scrutiny that modern drugs and medical procedures are routinely subjected to. And the results are, well, mixed.

A growing body of experimental evidence shows that acupuncture does indeed work, in some cases extraordinarily well. Another body suggests that it may very well work, but not for the reasons believers think. And yet a third body of “beats me” findings is sufficient to keep partisans on both sides arguing. In any case, something is clearly going on—and that something may, at least in some cases, be a cure for what ails you.

Crunching the numbers

AFTER COLDS AND FLU, PAIN IS THE MOST COMMON cause of visits to physicians—with lower-back pain clocking in at No. 1 on that very long list. Four out of five of us will eventually suffer from back pain of some kind. Untreated—or inadequately treated—it’s the most common reason for disability claims and employee absenteeism.

Acupuncture is often recommended as one way to treat the problem. In 2007, investigators at the University of Regensburg in Germany gathered a group of 1,162 patients with long histories of lower-back pain to determine whether it could actually make a difference.

Patients were given two half-hour treatment sessions per week for five weeks. About a third of the group underwent traditional, lower-back acupuncture, with needles inserted at the prescribed points. Another third got sham acupuncture, which involved real needles being inserted at random spots on the lower back. The remaining third received conventional treatment, consisting of physical therapy and exercise, along with the drugs they were taking.

At the end of the five weeks, the subjects were examined to determine how much pain relief they’d gotten and to what extent their physical functioning had improved. The results: 47.6% of the real-acupuncture group experienced significant relief in both categories; in the sham-acupuncture group, 44.2% did. For the rest, it was just 27.4%. The researchers sunnily concluded that “acupuncture gives physicians a promising and effective treatment option for lower-back pain, with few adverse effects or contra-indications.”

But does it? There is no denying that both groups that received some kind of acupuncture did better than the one that didn’t. But there’s also no denying that the results of the sham procedure make the idea of 360 carefully mapped entry points on the body look a little silly. The problem is, results like that aren’t at all uncommon in acupuncture research—and that’s not the best news for a treatment trying to prove its worth.

In 2011, for example, a study at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden separated patients suffering from chemotherapy-related pain and nausea into the same three experimental groups: real acupuncture, sham acupuncture and conventional therapy. This time the sham acupuncture involved blunt needles that didn’t even break the skin. Again, both the fake and real groups showed improvement—more than the Western-medicine group. In yet another study, this one looking at the effects of acupuncture on women trying to get pregnant through in vitro fertilization, sham acupuncture actually produced better results—a higher pregnancy rate—than the real thing.

“When a treatment is truly effective, studies tend to produce more convincing results as time passes and the weight of evidence accumulates,” wrote Harriet Hall, a former Air Force flight surgeon and an alternative-medicine skeptic, in a 2011 issue of the Journal of Pain. “Taken as a whole, the published ( and scientifically rigorous) evidence leads to the conclusion that acupuncture is no more effective than a placebo.”

Critics also point out that despite the common wisdom that even if acupuncture doesn’t help, it can’t hurt, there are, in fact, risks involved. Pregnant women, people with a bleeding disorder and people with a pacemaker (because of possible interference from the mild electricity that is sometimes applied to the needles) should be especially cautious. Even healthy people can suffer organ injury, infection or soreness if the procedure isn’t performed well.

Yet for every study that yields murky or even negative results, plenty of others present a clear win for the pro-acupuncture camp. Women going through menopause received significant relief for their hot flashes and mood swings with acupuncture, and those who got real acupuncture showed far more improvement than those who got the sham version. What’s more, blood tests bolstered the results, showing that the level of estrogen rose while luteinizing hormone fell significantly after real acupuncture—the opposite of the direction those hormones usually move during menopause.

Similarly, the National Institute on Drug Abuse found that real acupuncture—with needles inserted in spots in the ear said to modulate cravings—is overwhelmingly more effective than the fake kind or none at all in treating cocaine addiction. In patients who underwent the proper needle sticks, 53.8% had clean drug screens at the end of the study, compared with 23.5% of subjects who got the sham routine and 9.1% of those who received no acupuncture at all.

Whatever the exact numbers, some relief is obviously better than none, even if it’s sometimes conferred by what seems to be the power of the placebo. Besides, it’s an enduring truth of the placebo effect that in order for a patient to experience relief, something has to have changed in the body.

So when it comes to acupuncture—real or fake—what is that something?

How it works

FUNCTIONAL MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING (fMRI) has revealed that when volunteers are subjected to mild electrical shock while undergoing acupuncture, there is much less activity in four different pain-processing regions of the brain than usual. Although the pain stimulus continues, the brain notices it less. A fifth region—the anterior insula, which governs the expectation of pain—quiets down too. Often, the less pain you expect to feel, the less you do feel, a tail-wagging-the-dog phenomenon that is key to the placebo effect. If sham acupuncture produces only partial results, it may be because it affects only the insula rather than all the areas that deal with pain sensation. In any case, however, it is clear that something happens. “Acupuncture is supposed to act through at least two mechanisms: nonspecific expectancy-based effects and specific modulation of the incoming pain signal,” says Nina Theysohn of University Hospital in Essen, Germany, who conducted the fMRI study.

Naturally occurring brain opiates appear to be activated by acupuncture as well: imaging studies show that mu-opioid receptors—the molecular attachment sites that help nerve cells process the pain-relieving chemicals—have improved binding ability after treatment. Brain scans have also helped to validate an important part of the acupuncturist’s healing technique: the rotation of the needles that leads to something known as “de qi,” in which the body’s tissue seems to grab hold of the metal. There’s nothing mysterious about this; tissue fibers actually wind around the needle, making it significantly more difficult to remove. Patients may report a tingle or electric sensation when de qi occurs, and this too travels to the brain, quieting pain centers. The trade-off is a big payoff of analgesic effect for a little pinprick.

Ultimately, it’s this minimally invasive quality that makes acupuncture so appealing. Yes, a natural skittishness accompanies being punctured by needles, even exceedingly fine ones. And yes, those punctures can hurt a bit, depending on where the needles are inserted and how deftly. But once they’re in place, treatment requires nothing more than that you lie still and relax.

Maybe acupuncture produces enduring results and maybe it doesn’t. It is certainly the case that it appears more effective in relieving pain, stress and anxiety than it does with gastrointestinal or respiratory disorders. But as with any complementary treatment, it’s meant to be taken as part of a buffet of choices. And when you are suffering from something as frustrating as chronic pain, why wouldn’t you try whatever might help?

“It’s the effects of the treatment that are important to the patient, even if those effects are caused by unspecific factors,” says Linköping University’s Anna Enblom, who conducted one of the sham-acupuncture studies. Sure, we need to figure out what those factors are, but that’s a job for doctors and other scientists. The patient’s only job is to reap the rewards.

As the applications for acupuncture expand, the numbers of patients who are trying it increases.

An illustration from a medical guide explaining the ancient Chinese tradition of acupuncture

Studies suggest that pain receptors in the brain are activated by acupuncture needles.

Tackling the Opioid Crisis

Why alternative treatments may offer safer solutions

By David Bjerklie

Epidemics both instill fear and demand action. The epidemic of opioid-overdose deaths in the U.S. is a case in point: the country saw a sixfold increase in such deaths from 1999 to 2017. The crisis has driven dire headlines and resolute legislative measures, as well as a deluge of legal and financial action against Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin.

What has often been lost in the headlines is the fact that underlying the opioid crisis is an even larger medical crisis. More than 50 million Americans suffer from chronic pain, and far too many of them lack safe and effective options for managing it. In the urgency to address the opioid crisis, the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention issued guidelines for physicians to help patients taper opioid use to lower dosages or fully discontinue them.

This, in turn, fueled efforts by states to legislate prescription limits, by insurance carriers and pharmacies to cap the strength of prescriptions and by law enforcement to crack down on pill mills. Chronic-pain patients were seen as legally risky, and prescribers grew nervous about treating them.

Some pain experts pushed back, worried that patients would be abandoned. The CDC clarified its position, and finally the Department of Health and Human Services issued guidelines on the guidelines, attempting “to strike a balance between reducing the amount of opioids prescribed and ensuring patients aren’t left behind.”

In addition to debate over the guidelines, there thankfully are renewed efforts to expand approaches to pain management. In September 2019, the National Institutes of Health announced the HEAL Initiative (Helping to End Addiction Long-term), which will take an “all hands on deck” approach to the opioid crisis, tapping resources from across the NIH “to accelerate research and address the public health emergency from all angles.” It’s a billion-dollar program with the goal of finding safe and effective options for pain management.

“Our country, sadly, is in the midst of a pain crisis, as well as an opioid crisis,” says Helene Langevin, director of the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, who adds that non-drug approaches for chronic pain are a major research focus for the center. Studies have shown, says Langevin, that “approaches such as spinal manipulation, acupuncture and yoga can help people manage their chronic-pain symptoms.” Moreover, in many instances, these treatments can be first-line options. Another promising area of emerging research, adds Langevin, is “natural products, including cannabinoids and animal venoms.”

The NCCIH is aiming to develop both “new tools and new thinking,” says Langevin. And to remind us, above all, that pain demands a “whole person” approach. By deepening our understanding of the interactions between the brain and the body, she says, “NCCIH can establish the cross-disciplinary and integrative thinking needed to address pain in more comprehensive ways.” And that will save lives.

It Hurts So Good

Chiropractic and massage therapies are finding their way into the mainstream—for good reason

BY BRYAN WALSH

I’M LYING ON MY STOMACH, HEAD WEDGED INTO a cushioned face rest that leaves just enough space for me to breathe. The position itself should be sufficient to generate no small amount of apprehension, but there’s also this: I’m naked, save for the sheet draped over my posterior. Yet I’m as relaxed as I’ve ever been, the tension in my body—and especially that knot I’ve felt in my right side for years—dissolving in waves. I can even forgive the chanting that’s playing quietly in the background. All thanks to the massage therapist standing over me, her fingers kneading the small of my back, arranging and rearranging my muscles until I feel as soft and pliable as Silly Putty. At the moment, I don’t particularly care about the medical benefits of massage. All I need to know is that it feels good.

I have joined the blissful state shared by a growing number of patients taking advantage of what has come to be known as “manipulative medicine.” According to the National Institutes of Health, an estimated 18 million adults in the U.S. receive massage therapy each year. Chiropractors treat more than 30 million of us annually. Those are robust numbers for a pair of alternative practices that were once barely considered legitimate by the medical establishment. Decades ago the American Medical Association branded chiropractic an “unscientific cult,” and massage therapy still has to contend with a slightly seamy backroom reputation. But these days, manipulative medicine is pretty much mainstream. According to a 2011 survey by Health Forum and Samueli Institute, more than 42% of responding hospitals indicated that they offer one or more complementary and alternative-medicine therapies, up from 37% in 2007. Massage therapy was one of the top two services provided.

But even patients who swear by their massage therapist or chiropractor do so less because they know exactly why their visits make them feel better than because they simply do. They’re in good company. The fact is, doctors have only recently begun to understand the physiology of manipulative medicine.

For starters, studies have shown that massage therapy, which takes many forms but almost always involves rubbing, pressing or otherwise manipulating the soft tissues of the body, can increase the body’s output of endorphins and serotonin, chemicals that act as natural painkillers and mood regulators. At the same time, massage also reduces levels of cortisol, a stress hormone. Research published in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine suggests one explanation for this effect: scientists at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles found that a single deep-tissue Swedish massage led to a more significant decrease in arginine vasopressin (AVP) hormone than a control treatment of light-touch therapy. AVP constricts blood vessels and increases blood pressure, both of which are markers of stress.

Another study showed that massage turns off genes associated with inflammation and the pain that results from it. That, in turn, helps relieve the muscle soreness that follows physical activity or injury. Stack this anti-pain effect on top of the anti-anxiety benefits, and you can see why many hospitals have begun to incorporate massage therapy into postsurgical treatment.

The benefits of massage, however, really do go beyond the most obvious ones. Research by Tiffany Field, director of the Touch Research Institute at the University of Miami School of Medicine, showed that moderate- to deep-pressure massage can activate the vagus nerve, which helps regulate heartbeat. Field also found that massage can help with everything from depression relief to weight gain in premature infants, and she suspects that an energized vagus nerve may explain why.

Massage offers the kind of benefits that cancer patients can appreciate as well. A study published in the Journal of Integrative Oncology found that after learning massage techniques in short workshops, partners of cancer patients were able to give treatments that reduced anxiety, pain, nausea and other side effects of cancer by up to 44%. As is often the case with complementary treatments, the researchers hypothesized that it wasn’t so much the therapy itself as the intimacy of the contact that conferred the positive result. On the other hand, the Cedars-Sinai AVP study found that massage seemed to raise the production of the cancer-fighting white blood cells known as lymphocytes, and that is much less likely to be a result of such a placebo effect.

Neither cancer nor post-op healing is the primary battleground of massage. The condition that drives more patients to massage therapists and chiropractors than any other is much more mundane: back pain. According to the American Chiropractic Association, more than 30 million Americans suffer from back pain at any given time, and if you’re not among them at the moment, chances are you will be eventually. An estimated 80% of us will fall prey sooner or later.

And when you’re hurting, fast relief is all that’s on your mind. Research indicates that spinal manipulation—a chiropractor’s application of force at specific joints of the spine—is a good place to start. A study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine showed that chiropractic treatment of neck pain provided more relief than over-the-counter drugs like aspirin and ibuprofen. Specifically, after 12 weeks of treatment, more than half of chiropractic subjects reported at least a 75% reduction in pain, compared with one third of those in the drug group.

The improvement seemed to last—a year later, more than 50% of the chiropractic group still reported a significant decrease in pain. Meanwhile, those patients taking painkillers tended to have upped their dosage by the time of the follow-up, and that meant an added bonus for the members of the chiropractic group: they didn’t have to worry about the side effects the drug group was contending with.

Which isn’t to imply that chiropractic treatment is without controversy. Years ago neurologists noticed a pattern of people suffering strokes following chiropractic adjustment for neck pain. Many implicated the sudden neck-twisting that is central to the treatment, hypothesizing that it injured the arteries leading to the brain, thus triggering strokes. But more recent research is causing doctors to rethink that assumption. One study found that younger stroke patients were more likely to have complained about head and neck pain—symptoms that often precede a stroke—before their visit to the chiropractor, and that could mean they were already suffering the effects of damaged arteries before they underwent any manipulations.

If that’s the case, the only significant risk of manipulative medicine may be to your wallet. According to a 2010 survey by the American Massage Therapy Association, just 3% or so of Americans who got a massage over the previous five years were covered by health insurance for the treatment. Massage therapists aren’t considered licensed medical practitioners, which means their work isn’t recognized by most insurers. On the other hand, almost 90% of insured Americans are covered for chiropractic treatment, because licensed chiropractors, like physicians, have undergone four years of schooling.

For now, there is still no national standard for massage therapists, making it that much more important to scout out a therapist you can trust. Then again, anyone who is prepared to lie facedown and naked on an odd table in a room with a stranger has probably done that due diligence already.

Chiropractic treatment of neck pain may offer more relief than over-the-counter pain pills.

Kneads Test

Reflexology seeks to make connections from the feet up.

Move beyond the popular and straightforward kneadings of Swedish or shiatsu massage, and most versions of hands-on therapy continue to fall more under the heading of “if it feels good, do it” than “because it does good, do it.” Here are some approaches that it won’t hurt to try, even if in most cases there is limited evidence that they offer measurable relief.

Alexander technique

Named for the Australian-English actor F.M. Alexander, who developed it, this method focuses on the link between the body’s posture and movements and its physical problems. Stand or move differently, the thinking goes, and you can relieve or prevent injury. Though little research has been conducted on the Alexander technique, many doctors believe it is worth a try for anyone looking to relieve chronic pain.

Feldenkrais method

Think yoga, minus the obsession with specific positioning. This technique aims for dexterous and painless body movement with the goal of building better body awareness. That makes it similar to the Alexander technique. Another thing in common? Limited research on its effectiveness.

Rolfing

This deep-tissue massage was developed by the biochemist Ida Rolf, who discovered that the connective tissue surrounding muscles thickens and stiffens with age. Rolfing practitioners use fingers, knuckles and even knees to knead that tissue in an effort to loosen it up, improving posture and realigning the body. Some people find Rolfing helpful, but be warned: it can be painful, and certain conditions—advanced osteoporosis, for example----can be made worse by the therapy.

Reflexology

Popular throughout Asia, reflexology (which traces its roots to ancient China as well as ancient Egypt) works from the assumption that specific spots on the soles of the feet correspond to various other parts of the body. Massage the foot in a certain place, and relieve pressure or tension in the neck or even the liver. Although there is scant scientific evidence of its effectiveness, reflexology can’t harm you, and many people find it relaxing. After all, who isn’t up for a nice foot massage now and then?

Spinal manipulation

Lots of studies have shown that spinal manipulation can treat mild to moderate back pain—and certain other conditions such as headache as well. Some chiropractors believe that they can heal many other conditions and diseases by properly aligning the skeleton, but there isn’t much research to back up those claims. There are some risks, especially for those who suffer from osteoporosis or nerve damage. Those cracking sounds you may notice, however, are most likely all bark and no bite.