Food Cures

There may be no better-known adage than the cautionary advice “You are what you eat.” What researchers are newly discovering, however, is just how true and valuable that insight really is.

Just What the Doctor Ordered

The medical community is starting to consider the possibility that food is the best medicine

BY ALICE PARK

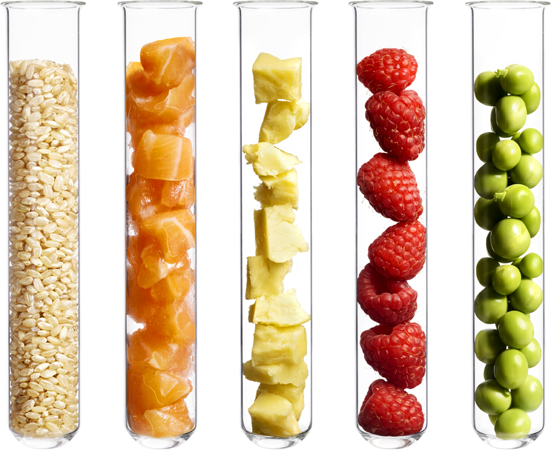

BLUEBERRIES They contain antioxidants that fight cancer. Studies show that some compounds in blueberries can interrupt tumors’ ability to grow new blood vessels.

WHEN TOM SHICOWICH’S TOE STARTED FEELING numb in 2010, he brushed it off as a temporary ache. At the time, he didn’t have health insurance, so he put off going to the doctor. The toe became infected, and he got so sick that he stayed in bed for two days with what he assumed was the flu. When he finally saw a doctor, the physician immediately sent Shicowich to the emergency room. Several days later, surgeons amputated his toe, and he ended up spending a month in the hospital to recover.

Shicowich lost his toe because of complications of Type 2 diabetes as he struggled to keep his blood sugar under control. He was overweight and on diabetes medications, but his diet of fast food and convenient, frozen processed meals had pushed his disease to life-threatening levels.

After a few more years of trying unsuccessfully to treat Shicowich’s diabetes, his doctor recommended that he try a new program designed to help patients like him. Launched in 2017 by the Geisinger Health System at one of its community hospitals, the Fresh Food Farmacy provides healthy foods—heavy on fruits, vegetables, lean meats and low-sodium options—to patients in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, and teaches them how to incorporate those foods into their daily diet. Each week, Shicowich, who lives below the federal poverty line and is food-insecure, picks up recipes and free groceries from the Farmacy’s food bank and has his nutrition questions answered and blood sugar monitored by the dietitians and health-care managers assigned to the Farmacy. In the first year and a half after he joined the program, Shicowich lost 60 pounds, and his A1C level, a measure of his blood sugar, dropped from 10.9 to 6.9, which means he still has diabetes but it’s out of the dangerous range. “It’s a major, major difference from where I started from,” he says. “It’s been a life-changing, lifesaving program for me.”

Geisinger’s program is one of a number of groundbreaking efforts that finally consider food a critical part of a patient’s medical care—and treat food as medicine that can have as much power to heal as drugs. More studies are revealing that people’s health is the sum of much more than the medications they take and the tests they get—health is affected by how much people sleep and exercise, how much stress they’re shouldering and, yes, what they are eating at every meal. Food is becoming a particular focus of doctors, hospitals, insurers and even employers who are frustrated by the slow progress of drug treatments in reducing food-related diseases like Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, hypertension and even cancer. They’re also encouraged by the growing body of research that supports the idea that when people eat well, they stay healthier and are more likely to control chronic diseases and perhaps even avoid them altogether. “When you prioritize food and teach people how to prepare healthy meals, lo and behold, it can end up being more impactful than medications themselves,” says Jaewon Ryu, the president and CEO of Geisinger. “That’s a big win.”

The problem is that eating healthy isn’t as easy as popping a pill. For some, healthy foods simply aren’t available. And if they are, they aren’t affordable. So more hospitals and physicians are taking action to break down these barriers to improve their patients’ health. In cities where fresh produce is harder to access, hospitals have worked with local grocers to provide discounts on fruits and vegetables when patients provide a “prescription” written by their doctor; the Cleveland Clinic sponsors farmers’ markets where local growers accept food-assistance vouchers from federal programs like WIC as well as state-led initiatives. And some doctors at Kaiser Permanente in San Francisco hand out recipes instead of (or along with) prescriptions for their patients, pulled from the organization’s Thrive Kitchen, which also provides low-cost monthly cooking classes for members of its health plan. Hospitals and clinics across the country have visited Geisinger’s program to learn from its success.

But doctors alone can’t accomplish this food transformation. Recognizing that healthier members not only live longer but also avoid expensive visits to the emergency room, insurers are starting to reward healthy eating by covering sessions with nutritionists and dietitians. In 2019, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts began covering tailored meals from the nonprofit food program Community Servings for its members with congestive heart failure who can’t afford the low-fat, low-sodium meals they need. In 2018, Congress assigned a first-ever bipartisan Food Is Medicine working group to explore how government-sponsored food programs could address hunger and also lower burgeoning health-care costs borne by Medicare when it comes to complications of chronic diseases. “The idea of food as medicine is not only an idea whose time has come,” says Dariush Mozaffarian, a cardiologist and the dean of the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University. “It’s an idea that’s absolutely essential to our health-care system.”

Ask any doctor how to avoid or mitigate the effects of the leading killers of Americans, and you’ll likely hear that eating healthier plays a big role. But knowing intuitively that food can influence health is one thing, and having the science and the confidence to back it up is another. And it’s only relatively recently that doctors have started to bridge this gap.

It’s hard to look at health outcomes like heart disease and cancer that develop over long periods of time and tie them to specific foods in the typical adult’s varied diet. Plus, foods are not like drugs that can be tested in rigorous studies to determine cause and effect in a simple, straightforward manner. Imagine how difficult it would be, for example, to execute a two-year study comparing a thousand people who eat a cup of blueberries a day with a thousand who don’t in order to determine if the fruit can prevent cancers.

Foods aren’t as discrete as drugs when it comes to how they act on the body either—they can contain a number of beneficial, and possibly less beneficial, ingredients that interact in complex and, in many cases, poorly understood ways in the body’s various organ systems. This physiological complexity can also be seen in studies that compare the health impact of foods versus the impact of isolated specific vitamins. While getting the right nutrients in the right quantities from food is associated with a longer life, the same isn’t true for nutrients from supplements, according to Fang Fang Zhang, of Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy. “For the general population, there’s no need to take dietary supplements.”

Doctors also know that we eat not only to feed our cells but also because of emotions, such as feeling happy or sad. “It’s a lot cheaper to put someone on three months of statins [to lower their cholesterol] than to figure out how to get them to eat a healthy diet,” says Eric Rimm, a professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. But drugs are expensive—the average American spends $1,400 a year on medications—and if people can’t afford them, they go without, increasing the likelihood that they’ll develop complications as they progress to severe stages of their illness, which in turn forces them to require more—and costly—health care. What’s more, it’s not as if the medications are cure-alls; while deaths from heart disease are declining, for example, the most recent report from the American Heart Association showed that the prevalence of obesity increased from 30.5% in 1999–2000 to 37.7% in 2013–2014, and 40% of adults have high total cholesterol.

What people are eating contributes to those stubborn trends, and making nutrition a bigger priority in health care instead of an afterthought may finally start to reverse them. Although there aren’t the same types of rigorous trials proving food’s worth that there are for drugs, the data that do exist, from population-based studies of what people eat as well as from animal and lab studies of specific active ingredients in food, all point in the same direction.

The power of food as medicine gained scientific credibility in 2002, when the U.S. government released results of a study that pitted a diet and exercise program against a drug treatment for Type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Prevention Program compared people assigned to a diet low in saturated fat, sugar and salt that included lean protein and fresh fruits and vegetables with people assigned to take metformin to lower blood sugar. Among people at high risk of developing diabetes, those taking metformin lowered their risk of actually getting diabetes by 31% compared with those taking a placebo, while those who modified their diet and exercised regularly lowered their risk by 58% compared with those who didn’t change their behaviors, a near doubling in risk reduction.

Studies showing that food could treat disease as well soon followed. In 2010, Medicare reimbursed the first lifestyle-based program for treating heart disease, based on decades of work by University of California, San Francisco, heart expert Dean Ornish. Under his plan, people who had had heart attacks switched to a low-fat diet, exercised regularly, stopped smoking, lowered their stress levels with meditation and strengthened their social connections. In a series of studies, he found that most followers lowered their blood sugar, blood pressure and cholesterol levels and also reversed some of the blockages in their heart arteries, reducing their episodes of angina.

In recent years, other studies have shown similar benefits from adopting healthy eating patterns like the Mediterranean diet—which is high in good fats like olive oil and omega-3s, nuts, fruits and vegetables—in preventing repeat events for people who have had a heart attack. “It’s clear that people who are coached on how to eat a Mediterranean diet high in nuts or olive oil get more benefit than we’ve found in similarly conducted trials of statins [to lower cholesterol],” says Rimm. Researchers found similar benefits for people who have not yet had a heart attack but were at higher risk of having one.

Animal studies and analyses of human cells in the lab are also starting to expose why certain foods are associated with lower rates of disease. Researchers are isolating compounds like omega-3s found in fish and polyphenols in apples, for example, that can inhibit cancer tumors’ ability to grow new blood vessels. Nuts and seeds can protect parts of our chromosomes so they can repair damage they encounter more efficiently and help cells stay healthy longer.

If food is indeed medicine, then it’s time to treat it that way. In his 2019 book Eat to Beat Disease, William Li, a heart expert, pulled together years of accumulated data and proposes specific doses of foods that can treat diseases ranging from diabetes to breast cancer. Not all doctors agree that the science supports administering food like drugs, but he’s hoping the controversial idea will prompt more researchers to study food in ways as scientifically rigorous as possible and generate stronger data in coming years. “We are far away from prescribing diets categorically to fight disease,” he says. “And we may never get there. But we are looking to fill in the gaps that have long existed in this field with real science. This is the beginning of a better tomorrow.”

And talking about food in terms of doses might push more doctors to put down their prescription pads and start going over grocery lists with their patients instead. So far, the several hundred people like Shicowich who rely on the Fresh Food Farmacy have lowered their risk of serious diabetes complications by 40% and cut hospitalizations by 70% compared with other diabetic people in the area who don’t have access to the program. On the basis of its success so far, the Fresh Food Farmacy is tripling the number of patients it supports.

Shicowich knows firsthand how important that will be for people like him. When he was first diagnosed, he lost weight and controlled his blood sugar, but he found those changes hard to maintain and soon saw his weight balloon and his blood-sugar levels skyrocket. He’s become one of the program’s better-known success stories and now works part time in the produce section of a supermarket and cooks nearly all his meals. He’s expanding his cooking skills to include fish, which he had never tried preparing before. “I know what healthy food looks like, and I know what to do with it now,” he says. “Without this program, and without the support system, I’d probably still be sitting on the couch with a box of Oreos.”

ORANGES They’re rich in vitamin C, which can increase the production of certain immune cells in the body. These cells can control overactive immune reactions in autoimmune diseases such as lupus.

FISH Certain fish are rich in omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 oils can reduce blood pressure and inhibit growth of plaques in arteries.

BROCCOLI This vegetable is loaded with glucosinolates, which convert to compounds that can slow breast-cancer cells from growing in the lab.

Vitamins Can’t Replace a Balanced Diet

A study finds that food beats supplements hands down

By Jamie Ducharme

Roughly 90% of American adults do not eat enough fruits and vegetables. That’s the reality. And so it’s understandable that many of these same folks are trying to make up for it by popping pills. According to the Council for Responsible Nutrition, three quarters of American adults take a dietary supplement of some kind. Multivitamins, many people believe, are an easy and surefire way to get all the essential nutrients they need.

But recent research published in the Annals of Internal Medicine suggests that vitamins and supplements may not be enough to keep you healthy. Nutrients consumed via supplements do not improve health and longevity as effectively as those that are consumed through foods, according to the study, which tracked 30,000 adults from 1999 to 2010. To be most effective, nutrients, it appears, should come from food.

Getting enough vitamin A, vitamin K, magnesium, zinc and copper, for instance, were all associated with a lower risk of dying early, the researchers found—but only when those nutrients came from food, according to co-author Fang Fang Zhang, associate professor of epidemiology at the Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy.

In fact, some supplements even appeared to come with health risks, according to the study. People who took high doses of calcium via supplement had a 53% higher risk of dying from cancer than people who were not taking supplements. But excess calcium from food was not associated with a similar uptick in mortality risk. Similarly, people who took vitamin D supplements but were not deficient in vitamin D had a higher risk of dying.

The study author does make the point, however, that some populations may indeed benefit from certain supplements, including the elderly—who often struggle to absorb nutrients from food—and those with dietary restrictions that may lead to deficiencies. But for most people, the best bet on a healthy future is to eat a balanced diet, not handfuls of supplements.

Your Friendly Microbes

Turns out your body is host to a whole world of organisms. How to make probiotics work

BY ALICE PARK

SCIENCE HAS LEFT FEW FRONTIERS UNCHARTED IN the human body. CT and PET scans allow us to peer through flesh into bones and organs. Genetic tests help us decipher the molecular instructions that guide cell growth. We can even watch the brain at work with MRIs that record neurons as they fire in the perfected choreography of cognition. Yet one vast universe remains largely unexplored, a world where interlopers outnumber homegrown cells by a factor of 10, and the DNA of which is composed of a whopping 8 million genes (humans, in comparison, have a paltry 23,000). It’s the microbial kingdom, an invisible ecosystem that can have profound effects on our health, influencing everything from our risk of cancer and obesity to immune disorders, asthma, colds, flu and maybe even autism.

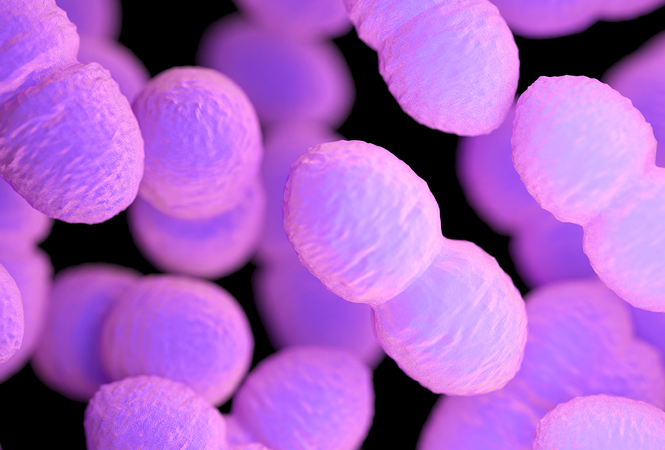

We tend to think of this unseen underworld as an army of disease-carrying invaders—bacteria, viruses and other pathogens that have us sniffling in bed or moaning in the emergency room. The fact is, though, evildoing microbes are the exception. The vast majority of bugs that live in, on and around us are good neighbors—allies, actually—performing functions essential to good health. “Tens of thousands of species of microorganisms live with us,” says Lita Proctor, who coordinated the Human Microbiome Project, launched in 2007 by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). “They belong there, they’re good for us, and they support health and well-being.”

Consider the microbes that reside in the gut, by far the human body’s largest community of tiny tenants. Most are bacteria with odd-sounding names like Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, but they perform the vital function of producing enzymes that break down plant fibers. Without them, we wouldn’t be able to absorb the nutrients and vitamins found in leafy vegetables and legumes. Other bacteria ferment digested food in our intestines, helping transform what we eat into the energy our cells need.

The goal of so much of the medicine we take and therapies we undergo is to rid the body of microbes. But now that we are beginning to realize the benefits of these organisms, scientists are developing treatments that do just the opposite: seed the body with them. This blossoming field, known as probiotics, shares its name with the class of “good” bacteria it uses, and its potential as a wellness tool is virtually limitless.

Our relationship with beneficial microbes goes back a long way, to our very first moments in the world. The womb is a sterile environment; delivery is a newborn’s first confrontation with germs. Over the course of a pregnancy, the makeup of the bacteria in the vagina—the vaginal microbiome—changes, and by the end of nine months it’s a well-represented community of bugs that an infant is likely to encounter in the outside world. This initial inoculation primes a baby’s immune system to identify potentially troublesome pathogens and mount appropriate immune responses against them.

The journey through the birth canal is an important one. Intriguing preliminary evidence suggests that the makeup of the vaginal microbiome can influence a child’s later health, possibly causing, for instance, the development of asthma and allergies. Similarly, scientists hope to tease out microbial “profiles” that characterize babies who might be susceptible to certain illnesses; some research indicates that gut microbes adjust to what we eat and react to the air we breathe and illnesses we encounter.

Figuring out how these microbial populations respond to stimuli will open whole new treatment paths—and maybe even help us avoid sickness in the first place. Over the span of a decade, the NIH invested $170 million in the Human Microbiome Project, which ended in 2016. Modeled after the Human Genome Project, which sequenced the body’s genes, the Human Microbiome Project sequenced about 3,000 bacterial genomes from samples collected from more than 300 people.

Good germs, bad germs

SOME BUGS DESERVE THEIR BAD REPUTATIONS, while others do not. Our bodies have both kinds in abundance. Researchers hope to create a database of microbes that will help link particular communities to either disease or improved health. “This is a vast territory we’ve never studied,” says George Weinstock, professor of and director for microbial genomics at Jackson Laboratory in Farmington, Conn.

Why has so much remained out of reach until now? For starters, many of the bacteria are difficult, if not impossible, to grow outside the inviting confines of the human body. That has made it challenging for microbiologists to get an accurate tally of what resides within us, much less figure out what the organisms do. But advances in DNA sequencing now allow researchers to bypass culturing altogether. Essentially, they use genetics to take bacterial attendance, filtering out recognizable human genes from a sample and then logging the remaining DNA. The latest investigations have uncovered some tantalizing clues about the dramatic effects this microworld can have on our health. Scientists have learned, for example, that obese people and people of normal weight harbor different bacteria in their intestines and that the composition of bacterial communities changes depending on what you eat. People who favor high-fat, low-fiber diets tend to house more Bacteroidetes bugs, while those who eat less animal fat show higher concentrations of Prevotella microbes. From a therapeutic perspective, it would be important to know if this relationship works the other way too; that is, can different types of gut flora influence or even change eating habits?

What does seem to be true is that tweaking a person’s microbial profile can improve his health. Studies hint that probiotics, in particular lactic-acid bacteria and bifidobacteria, can thwart cold and flu viruses, resulting in 12% fewer respiratory infections among children and adults given them, compared with a control group. More encouraging, probiotics may help cold and flu sufferers reduce their antibiotic dosage—a huge plus given the growing problem of antibiotic-resistant bugs.

In another recent treatment advance, patients with C. difficile infections, which can cause persistent diarrhea, abdominal cramping and fever, have been administered fecal transplants. Yes, that is just what it sounds like: infusions of feces from an uninfected, usually related, donor.

In a paper published in 2017, researchers led by Dina Kao, a gastroenterologist at the University of Alberta in Canada, reported that fecal matter manufactured into a capsule was as effective as delivery by colonoscopy. Another delivery vehicle is a tube inserted through the nose into the stomach. “The biggest question in this area has always been, what’s the best way to deliver the transplant?” says Kao. The treatment remains experimental and has not yet received FDA approval, but it is widely considered very promising and is gaining momentum.

Similarly, doctors at some cancer centers advise patients to bank stool samples—essentially, a concentrated form of their microbiome—before chemotherapy, just as they might store blood for transfusions, to replenish what the toxic treatment wipes out. Early studies show that patients who do this rebound quicker from their chemo course than those who don’t.

Then again, doctors don’t expect fecal transplants to become as common as flu shots. “I think that in the not-too-distant future we will be able to have probiotics or dietary supplements to support beneficial microbes,” says Proctor. Some of those may be composed entirely of strains of probiotics, while others, known as synbiotics, may be combinations of probiotics and prebiotics. Prebiotics aren’t microbes at all but rather indigestible parts of the foods we eat (say, the fiber in whole grains) that nourish the good bacteria.

Some consumer-ready probiotics may already exist in your grocer’s dairy case. The makers of Activia yogurt say their product eases digestive disorders by repopulating the stomach with healthful bacterial colonies. Then again, they may have gotten a little ahead of themselves, having landed in court as defendants in a class-action suit that alleged false and misleading advertising claims.

That doesn’t mean those claims won’t eventually be proved true, though. Once we fully understand how microbes morph in response to what we do and what we eat, not to mention environmental factors, we will be able to manipulate them to our benefit. Further, many of these bacteria interact with each other to produce enzymes, digest food and fight inflammation, intimately connecting them to the body’s metabolic processes. Playing on that field—tweaking the pathways by which compounds and chemicals pass back and forth—will lead to the most significant advances.

Imagine being able to overcome obesity simply by adjusting the makeup of the gut’s ecosystem, or saving patients from a fatal infection by giving them some microbes to ingest. That’s the promise of the human microbiome, the hidden world that isn’t likely to remain out of sight for long.

Babies arrive in the world inoculated with microbes that prime the immune system.

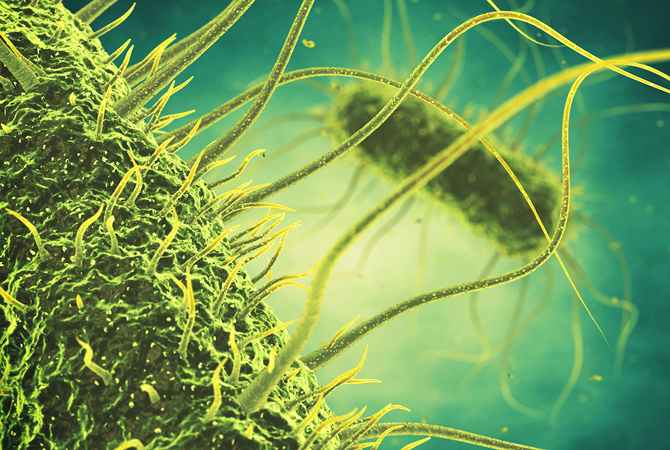

E. COLI: This is a much-maligned bacterium, and for good reason: it can cause deadly disease. But that’s not the whole story. Some strains, naturally occurring in our abdominal tract, aid digestion and keep bad microbes at bay.

ENTEROCOCCI: Found in the vaginal and intestinal regions of 40% to 80% of people, some strains of this bacterium cause infection, but many others make our immune system more efficient.

SALMONELLA: Unlike E. coli, salmonella deserves its reputation. A lot of what we call food poisoning comes from strains that are found mostly in raw eggs and chicken but can turn up almost anywhere. In the worst cases, salmonella poisoning kills.

LACTOBACILLUS: This bacterium ferments milk into yogurt by converting lactose, a sugar found in milk, into lactic acid, which acts as a preservative and gives yogurt its tart flavor.

A Helping of Probiotics

Although the study of probiotics continues, early indications are that most people tolerate them well. (Children, the elderly and those with compromised immune systems may want to stay away until we know more.) Here are some ways to add a little probiotic flavor to your everyday diet.

› Mix plain yogurt or kefir (a fermented milk drink) with fruit and a little sweetener for a snack or dessert or as a base for smoothies and ice cream.

› Use miso, a soy-based seasoning, in soups, marinades and salad dressings. Another soy product, tempeh, can sub for meat in sandwiches, spaghetti or chili.

› Top a sandwich or accompany an entree with sauerkraut.

› Feel free to treat yourself to a bar of good-quality dark chocolate or a glass of wine—but only once in a while.

› Thirsty? Search out probiotic soy beverages and fruit drinks in your local supermarket.

› Probiotic supplements, in capsule and powder forms, are available. But use them only as directed and after consulting a caregiver.

› Antibiotics may go after your body’s good bacteria as well, so when your doctor prescribes them, ask about taking a probiotic supplement too. But be sure to

take the medications at least

two hours apart.

› Similarly, some foods may promote the growth of your local flora. These “prebiotics” include wheat, barley, oats, chicory root, artichoke, banana, garlic,

onion and honey.

—Charla Schultz

Scientists are learning that the microbial communities in our guts are linked to everything from body weight to asthma to acne. Having the right balance is key.

Secrets About Dietary Cleanses

From fasts to flushes, many of us will do whatever it takes to cleanse our body of toxins. But what if we don’t have to do anything at all?

BY PEG ROSEN

“I JUST FINISHED A DETOX, AND I FEEL AMAZING.”

Many of us have heard some version of that sentiment from friends, family or someone at work. Or maybe we’ve read about a celebrity touting the benefits of a cleanse, the practice of subsisting for days on green shakes, highly restrictive diets or even plain water to rid the body of impurities. We can certainly understand the motivation, and we might even believe that a person who has undergone such a regimen does indeed feel amazing. But the reality is that there is little research that endorses the notion that attempts to “detox”—unless the toxins, are, say, addictive substances like drugs or alcohol—are effective. Or even necessary.

That’s because the human body does a decent job of scrubbing itself clean all on its own. Our liver, kidneys, lungs and skin exist in large part to filter out impurities, eliminating them in sweat, urine, breath and feces. Bacteria in the colon neutralize food waste, and that organ’s mucous lining prevents potentially harmful organisms and waste products from seeping back into our system. And while some toxins are absorbed by fat cells—where they can take up permanent residence—there’s scant evidence to suggest that we can forcibly flush them out.

Cleansing, though, is no fad. Versions of the practice have been championed for millennia. Ancient Egyptians purged their colons at specific times during the lunar cycle. The Greeks believed that eating allowed “demonic forces” to enter the body and embraced fasting as an antidote. A vast array of religions and spiritual traditions have also incorporated fasting into various ceremonies and rites. Twentieth-century guru Paramahansa Yogananda, who was born in India and died in Los Angeles, said simply, “Fasting is a natural method of healing.” Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that today, therapeutic cleansing basks in a continuous cultural limelight, thanks to an ever-changing but endless parade of A-list celebrity enthusiasts.

All hype aside, the idea that dramatically restricting what goes into the body, at least for a limited time, may be beneficial isn’t totally unreasonable. “There is a decent amount of research on fasting. Threads of evidence suggest there may be some benefits,” says Mary Beth Augustine, a consulting integrative nutritionist. Animal studies have shown that intermittent fasting slows brain aging and reduces cancer risk. There is also research suggesting that periodic fasting may trigger changes in metabolism that lower the risk of coronary heart disease and diabetes.

Is less more?

BUT THAT HARDLY JUSTIFIES THE SWEEP OF THE assertions made in best-selling detox books. Many juice fasts claim to offer weight loss, relief from bloating, the elimination of unspecified toxins, a general boost to the immune system and, in some cases, a reduced risk of cancer and other diseases. One modified juice fast, the Master Cleanse (also known as the “lemonade diet” because it features a concoction of lemon juice, maple syrup, cayenne pepper and water), purports to flush undigested food and built-up waste from the body.

Food-based detox diets, which regiment the intake of solid foods and are sometimes accompanied by supplements and laxatives, allegedly expunge targeted disease-causing bacteria or cleanse particular organs of stored impurities. The draw of colonics, also known as colonic irrigation or colonic hydrotherapy, is even more visceral. The goal of this process, in which up to 15 gallons of fluid are flushed through the colon by means of a tube inserted in the rectum, is to remove fecal matter that has built up in the digestive tract. Backers of the treatment buy into the theory of “autointoxication,” which holds that fecal toxins leach back into the body, causing a range of maladies from fatigue to allergies.

It can all sound pretty persuasive. And sure, otherwise healthy individuals may feel less bloated or lose weight on many of these routines. But think about it: these fasts and diets by definition restrict caloric intake and specifically exclude processed foods, caffeine, alcohol, fatty animal protein and excess sodium. What health professional would argue with that regimen? If you feel good on a juice fast, it’s probably because of what you are not consuming.

On the plus side, few of the therapies are especially risky—with the exception of colon therapy. An improperly administered colonic may result in a host of complications, ranging from bowel perforation and infection to reduced kidney function, electrolyte abnormalities and possibly even heart and kidney failure. Vomiting, dehydration and the obliteration of helpful bacteria that keep the bowel environment in healthy balance have also been reported.

Also of concern can be liver flushes, which may lead to explosive diarrhea. In rare instances, a flush may cause cramping that dislodges a gallstone that then dangerously becomes stuck in a bile duct. Really, though, the biggest downside of these flushes, specifically when they are used to eradicate gallstones, is that they delay individuals from seeking more conventional treatment.

But those are worst-case scenarios of more-extreme therapies. For people in generally good health who aren’t pregnant, breastfeeding or severely underweight, juice fasts of a few days or even weeklong restricted cleanse diets won’t hurt. In fact, they might even do some good. Many cleansers experience post-treatment exhilaration. It might be little more than a placebo effect, but that’s OK; you can ride that feeling and jump-start more permanent dietary and lifestyle changes. “It’s one reason why—even if it’s not my choice as a first-line treatment—I support my patients who want to try it,” says Augustine. Because in the end, of course, it’s long-term, consistently maintained dietary changes that make us healthier. Anyone in the cleansing game for a quick fix is wasting his time. And that’s mostly because the majority of cleansers revert to old habits after treatment, often with a vengeance. Whatever pounds were lost are gained right back. Worse, that can trigger a vicious cycle of yo-yo dieting in an effort to hold one’s ground.

“My clients often come in telling me they want to do a cleanse to get back on track,” says Andrea Giancoli, a nutrition communications consultant, who understands the impulse to start big. “But why not just do something that gets you on track and allows you to stay there? If you really want to do a cleanse, cleanse your fridge and your pantry.”

A cleanse has a definite appeal, but for a real overhaul, try cleaning out the fridge.