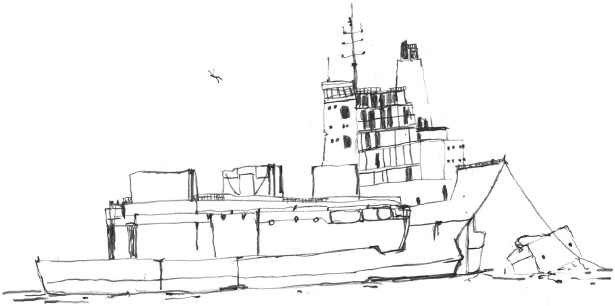

There are many men there, thousands of them. But they do not weigh as much as the machines. The men are crawling all over the ships. The ships have been pulled out of the water using big winches that are sunk into the sand on the beach. The winches alone outweigh the men. They pull the ships up onto shore, then the men are released to swarm them. They cut them to pieces with oxygen torches and acetylene torches. The pieces they cut fall off and are very large. Sometimes, the pieces are as big as buildings. The fat man, the owner of lot 161, told us that five men die in Alang each year. Will sensed that he was lying, and I did too.

Once the pieces are on shore, they are dragged up the beach by the men. Sometimes the machines help. The pieces are just slices of ship. Sometimes, the slices come from the front of the ship, like bread slices. Other times, the slices come from the sides, like turkey slices. Either way, they must be picked apart.

It is interesting to see what is inside a big ship like that. I got to look right inside. I could see the rooms. Sometimes the plumbing is visible, or stairs. Sometimes the insulation is. Will told me that one reason the number of deaths is higher than five is because there are no masks or filters in the ship-breaking yard. Whatever comes out of the ship, if it is not scrap metal or something usable (like a lifejacket), is set on fire.

Sometimes an oil tanker arrives. In these cases, the tanker is cut open on shore and the oil spills out. That is why the Alang coast is brown. I thought that anyway, and I told Will. Will told me that the coast is always brown in India, not just in Alang. I walked down to the mud and smelled it. It smelled like shit. Will told me that is because the workers do not have any plumbing in their homes.

Will is a factory worker from Tulsa, Oklahoma. For this reason, he was more adjusted to the environment of the Alang ship-breaking yard. For example, when we approached the ships, after we were frisked and interrogated a little, we walked over a piece of metal that was being cut by two men wearing no shoes. The cutting was happening with what was either an oxygen torch or an acetylene torch. The sparks were quite hot, but we walked right through them. There was very little air to breathe. The smoke, combined with the chemicals, the exhaust of the machines, and the stinking ocean made it so I hated my own breathing. Will said that was normal. I was unable to cover my mouth with my T-shirt because I was supposed to be a hardened factory worker like Will and not just some idiot with a notebook.

I saw a worker there and I told Will that he couldn’t be older than 15. Will said that was bad. But then he told me that he started work in a foundry when he was 17. It wasn’t good, he said, but he really couldn’t judge.

Later, we stood underneath a crane that was handling a large piece of a ship. It was swinging over our heads. I was nervous to be beneath this piece of ship. The piece was bigger than a van. I was afraid the piece would fall and crush us, but again Will said this was fairly normal. The ship they were breaking was Japanese. It was constructed in 1999.

I asked Will if he thought human rights abuses were happening in the shipyard in Alang. I told him that I had read in many newspapers that these ship-breaking yards were the scene of human rights abuses. In fact, I believed that I had seen some with my own eyes. Will said he didn’t really think so. He said the pay was better here than in many parts of India. Besides, he said, the conditions were not that much worse here than in the average factory. The reason the shipyards were big news was because Westerners felt guilty that their ships were being broken up here.

We sat with the owner of lot 161. His face was so round and so pudgy that his eyes were really squinty and gangster-looking. I do not know if he was actually evil, though. While we were with him, he received a delivery which he unwrapped and passed around for Will and me to look at. The delivery was a very ornate box. The box was made of very fine wood and had beautiful engravings all around it. Inside of the box was a book with what looked like original Persian miniatures on it. They depicted a king with his entourage. The king was on a horse. Inside the book was a wedding invitation. “Save the date, only,” the fat man said.

The fat man was wearing a gold watch and had tea delivered to us. I did not take any. I told the fat man’s assistant that I was sick to my stomach. The assistant became afraid of angering the fat man, who rarely hosted foreign dignitaries such as ourselves. After all, foreigners could not be trusted in a place like Alang. They tended to leave and say nasty things about the operation there. They tended to distort the truth and exaggerate things like human rights abuses and environmental catastrophes. Foreigners were obsessed with Alang, the fat man said, because they did not understand it. We were seated on a veranda overlooking the struggling shipyard, which was teeming with workers. There was a noise like thunder from the next lot. A thick plume of smoke intermittently blew into my face. It was dark brown.

While we were sipping tea and examining this ornate box, two men were disassembling a cylinder that was composed of hundreds or thousands of greased-up pieces of wire. The wire was thick like rebar. Each piece was stuck through two circular metal plates. Heat exchanger, Will said. The men were removing each piece of wire by hand, but it was so greased up that their hands kept slipping. Each piece took them five minutes or so to remove. They were not even close to finishing. The cylinder was more than a meter in diameter. The men had to strain a lot to remove the wires. Behind them, a group of seven men lifted one giant piece of scrap after the other into the bed of a large Indian dump truck. They lifted as a team, like this: “Ho! Ho! Hup!”

We drove along the beach at Alang to see how big the place was. It went on and on. For 10 kilometers there was one giant ship after the other. I liked looking at these ships and seeing their insides, but it was very depressing to consider that each of these lots had a fat man, an ornate box, and men pulling wires out of cylinders. Each lot had a tall gate and a mean-looking man in front of it to keep out people such as ourselves. The gates were painted with motivational messages such as “Clean Alang, Green Alang” or “Safety Is Our Motto.”

Will loved to look at the big engines. They were bigger than a house. They were covered in valves and exhaust pipes big enough to walk through. “What happens to them?” I asked Will.

“Scrap.”

We were not supposed to be in there. We didn’t have a permit or anything. We were told that we could go to jail if we were caught.

Nowadays, the value of a big ship like that is only determined by its weight. The human labor and knowledge and design and so on are negligible to the price. That is how cheap human labor has become. Nowadays, things like ships are measured by the kilo. This is something the fat man explained to me, as we were standing beneath that crane, beneath that piece of ship that was bigger than a van.

The homes for the workers at Alang are made of plastic sheets and scraps of wood and tarps and so on. When they need to use the bathroom, they wander out into the ocean.

The ships are bought as is. That means that when they are hauled up on to shore, everything is still inside of them. The beds, the maps, the lockers, the exercise equipment, ropes, lifeboats, blenders, spoons, and so on are all still there. Outside Alang, there are open lots or rudimentary warehouses holding all of these things for sale. I saw a whole warehouse full of treadmills. Another was just couches. It was really amazing. All of these things were along one long road leading to the ships themselves and the brown beach. I measured the distance from one end of this road to the other, and the distance was six kilometers. On both sides of that road were continuous piles of ship stuff that reach higher than a house. I probably saw over one thousand blenders from all around the world.

Also with Will and me was the German intern. The German intern was interested in one day entering manufacturing or a related field. He, like Will, did not really seem to be disturbed by Alang. The two of them ate a lot of food at a restaurant right outside the road with all of the stuff on it. I could not eat though.

I told them that when I was a kid, I used to kill ants. I would squish their legs and then I would use a magnifying glass to cook them. The smaller my spot of sun, the better the ant would burn. It would pop and sizzle when it cooked and curl up as the ant got heated by the sun. “Yes,” the German intern said. “That is universal.”

Will is an engineer and he is pretty good at math and at figuring things out. I asked him after I returned from India whether he thought human beings weighed more or machines did. In other words, if you stacked up all humans on a scale, and then all machines, which one would be heavier?

“There are about 6 billion humans at about 60 kilos average,” Will wrote to me. “That’s 0.36 gigatons.”

Will wrote that he read in a book by Vaclav Smil that humans use 1.5 gigatons of stuff each year just in order to “keep the ‘human edifice’ going. But that includes a lot of cement and sand and stuff.”

He wrote that in his apartment, the machines he had weighed more than him. “Fridge, air conditioner, ghetto blaster, etc.”

He wrote: “The total number of cars produced last year was 80 million. And the total number in existence is now more than a billion. The average car weighs more than 1.5t. This means that cars alone outweigh humans by four times: 1.5 gigatons of cars vs 0.36 gt of humans.”

As we were leaving Alang, there was a truck that was painted in orange, with dots of every color on it. It had paintings of eyes on its front, and on the back it was written: “All is All.” The truck was being loaded with scrap, which would be melted in a furnace somewhere and turned into auto parts, machine parts, gears, and so on. The ships’ ballasts, giant redwood trunks made of forged steel, were taken away to be turned on lathes for weeks, making them into molds for the pipes that run beneath our cities. The lathes turn in a workshop in Ahmedabad. It is nice there. It is peaceful. The hum of the lathes never stops, these big redwoods turn and turn, spiral-shaped steel shavings pile up on the floor, and the men wade around through those, carefully checking the slow progress of the molds. Then the molds are brought to factories and filled with liquid steel. Then more cities are built. And ships are made to supply them with all the things they need.

In Ahmedabad, Will and I went up in a hot air balloon. It was tethered to the ground by a steel cable, and the cable was controlled by a winch, which was bolted to the ground. We could see for miles. The city was full of cars and motorcycles and dump trucks and construction equipment. The buildings were all falling down and rebuilt as they fell, so signs and laundry lines came out at odd angles. Police in khaki uniforms used long sticks to control the traffic, beating the cars like sheep. Women dressed in the brightest colors. People piled into any kind of motorized transportation. There was a ring of smoke around the city. Four industrial zones, all with hundreds of smoke stacks, released black lines that drifted the same way, out over the plain to the seaside. The industrial zones surrounded the city, so it always smelled like burning, even high up. “I hate to ask this,” I told him, “but what do you think would happen if the cable broke? We would fly to space!”

Will laughed. “It wouldn’t even make the news,” he said.

I used to have this nightmare where I found myself standing inside of a giant mouth. The mouth was as big as the universe and was lined with sharp teeth pointing downwards. In the nightmare, I am holding onto a tooth and all around me, human bodies are falling down into the mouth. Millions of them, people from all over the world. I told Will about this. I said that was kind of the feeling I got when I was in Alang—that we were all falling down into some kind of abyss, and that it was completely out of our control to stop it. That it wasn’t progress that was moving us, but gravity. I told him I needed a bit of time off from looking at machines.

A few days later, we were drinking whiskey and Will and the German intern were discussing Alang. They said that it was not a humanitarian problem or an environmental problem. They said that like all problems, it was an engineering problem. The solution to all of these machines, they kept insisting, was more machines.

I told them that I thought they were maniacs.

“Listen,” Will said. “I’ll draw it out.”

He proceeded to redesign Alang with locks for raising the ships and for holding in spilled oil. There were big cranes to hold up the ships and the ship pieces so they wouldn’t fall and crush the workers. He put robotic torches on robotic cars on these same cranes to do the heavy cutting. He insisted that it would be quiet and clean. He said that humans would only have to push the buttons. It could be a good operation, he said. Clean and efficient and humane. It would even be cheaper than it is now. More profitable.

I looked at his drawing and I had to admit that it seemed like a very good idea. Much better than the way it was now.

“So why don’t they do it?” I asked.

“Folks are just too busy whipping their workers to think about the numbers,” Will said. “Quite common.”