This is your new home in Seattle. It is an apartment complex located next to a bar called Waid’s. When you read the requirements for tenancy application, a simple sentence stood out to you. Households must have monthly income of at least 2.5 times the rent and must not exceed 60 percent of area median income limits. This sentence is nearly incomprehensible to you, like an image hidden inside a painting, visible after staring at it endlessly. You are able to afford living there, you know that much, but it is not something you would brag about at the bar.

On the last day of February you walk outside your brand-new apartment building, eager to explore your new city. It happens almost instantly at six in the evening, too early and too bright for this type of situation. You later describe him to the police as an unknown race male, wearing a gray hoodie and dark blue jeans with a design running down the side. He threw you to the ground face first and you barely managed to lift your hands to blunt the fall. In the bathroom a few hours later, you rub alcohol on the cuts to your palms and forearms. While you are down on the sidewalk, he takes the smartphone and wallet from your back pockets. When you look up he is running away, nothing more than a blur of gray hoodie and dark blue jeans with a design running down the side.

The man is never caught. Many people in your building believe all the crime around the building comes from the bar next door. You have been to Waid’s before and had a good time dancing with strangers. You don’t agree with your neighbors but they don’t listen to you and insist that drug dealers and gangsters frequent this bar. It’s not as if you try very hard to convince them otherwise, and if you pressed the issue any further, they would probably accuse you of calling them racists. Waid is a black Haitian man and there weren’t so many white people on the dance floor the nights you were there, so you suspect that maybe they are racist.

March arrives and you try to feel at ease in your neighborhood but it is difficult. You notice yourself flinching whenever you see a gray hoodie and sense someone walking towards you quickly. It is difficult to expel this anxiety and so you try a variety of things. You begin dressing in frumpy clothes, you visit the parts of Seattle your neighbors consider dangerous, you go to Waid’s every Saturday night, and eventually you start wearing a gray hoodie. But despite all of your efforts, you still see him out there, bringing sweat to your armpits and quickening the beat of your heart.

One afternoon near the end of March, the Seattle Police Department sends you a terse, institutional email. Your phone reported stolen on February 28th has been located. Your phone can be retrieved at the East Precinct. You call the precinct for a response but are unable to reach anyone. Later that evening you go to the precinct and collect your phone from the red-faced cop working the front desk. It is in the same condition as when you last held its silver and black frame, but when you turn it on, you realize all of your information has been erased. It is an entirely new phone.

“How do you know this is my phone?” you ask the cop.

“We can keep it here if it’s not yours.”

“No, it’s my phone, but none of my information is there anymore.”

The telephone rings, the cop answers it, and you instantly grow frustrated. There is no point in remaining at the precinct so you head back to your apartment. You scour the local blogs looking for answers until you stumble on the SPD crime blotter and find them.

It seems as if the man who stole your phone took it to a place called One-Stop Wireless in Little Saigon. According to the SPD, people would line up every morning at 10 and wait to sell whatever electronic commodity they had stolen the night before. When the cops raided the shop, they found over 800 computers and phones waiting to be resold to anyone with access to this black-market network. It occurs to you that no one has ever offered you a stolen phone, nor have you ever known a thief in person. Illuminated by this simple thought, you begin to randomly scroll through the SPD crime blotter until you find something entirely different.

A few nights before, someone tried to burn down an under-construction apartment complex just up the hill from your own building. They threw two Molotov cocktails at the structure but only one of the devices shattered. Because of the rains that had recently drenched the city, the fire did not spread and the structure was not destroyed. In your imagination, you see the man in the gray hoodie throwing a bottle of fire at a shadowy construction site. No matter how hard you try, you cannot visualize his face, even when it is lit by flame. But then you realize what must obviously be true. The person in the gray hoodie was a woman. This is when you actually see her.

At first it is like a dream, but there she is, standing on the corner, just below your third-floor window, and not only is she there, but she is looking at you, clearly smiling. In her hand is a cell phone and over her skinny frame is the same gray hoodie she wore a month ago. With her eyes locked on your own, she raises her free hand and waves at you. In this moment, you fall in love.

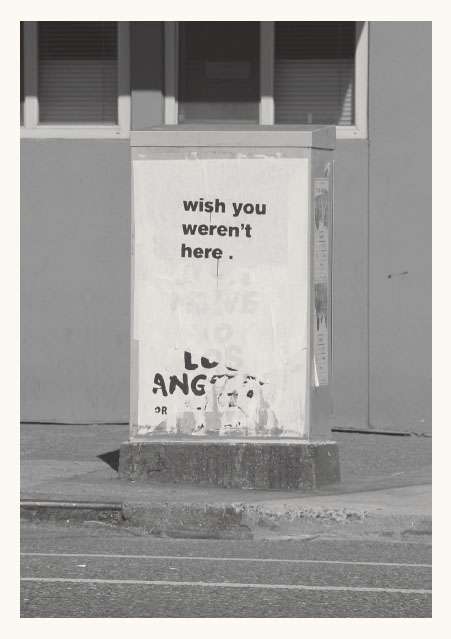

John Criscitello, Welcome Rich Kids, 2014, Wish You Weren’t Here, 2015