Getting Past Penelope Swords

My great-grandmother, Ansibelle Penelope Swords Holder, was an enigma, and represented one of my most difficult research “brick walls.” I have mentioned her several times in this book because the methods I used to get past the gridlock are good examples of alternative research strategies that you will sometimes need to employ. The research techniques and resources described represent the types of approaches that are often necessary to work around brick wall problems.

Defining the Problem

M y childhood memories are peppered with recollections from my mother and her three sisters’ discussions of their own mother’s parents, Green Berry Holder (1845–1914) and his wife, Ansibelle Penelope Swords (1842–1914), of Rome, Floyd County, Georgia. It was not until my early twenties that I began to look in all seriousness at the ancestry in my maternal line. When I did, it was comparatively simple to document—first, my mother and her three sisters, and second, my grandmother, Elizabeth Holder, and her five sisters and five of her six brothers. (One of her brothers, Brisco Washington Holder, left home and traveled as an itinerant worker for much of his life. His story was another brick wall challenge I worked on for almost 20 years.)

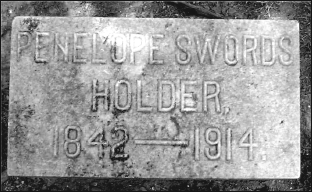

Ansibelle Penelope Swords Holder (1842–1914).

My great-grandfather, Green Berry Holder, had been a Confederate soldier, and was the first postmaster of two federal post offices, a farmer, a merchant, founder of the North Georgia Fertilizer Company, owner and president of the Rome Mercantile Company, a board member of two banks, an elected representative from his county to the Georgia State Legislature for two non-consecutive terms, a real estate investor, an insurance salesman, a member of the United Confederate Veterans, a member of the Rome Presbyterian Church, and a member of a singing group.

As you can imagine, there were lots of records about him, and from those records I was able to link him to an older brother, also in the Confederate Army, and to their parents in Lawrenceville, Gwinnett County, Georgia. Unfortunately, though, the records for his wife were far from numerous, as was typical for women of that era. In fact, for quite a while, the only real record I had was her gravestone. My research problem was to locate information about my great-grandmother, identify her parents, and be able to continue my research in her ancestral line. In the course of my research, I found that most records referred to her as Penelope. My mother’s sister, Carolyn Penelope “Nep” Weatherly, received her grandmother’s middle name as her own. She, my mother, and their other two sisters were aware of their grandmother’s full name. They often laughed that it was a good thing that Nep had not been given the name of Ansibelle. Other records I discovered, however, listed my great-grandmother’s name as Annie, A. P., Annie P., Nancy, and Nancy B., or some other misspelling of Ansibelle. •

Gravestone of Penelope Swords Holder at Myrtle Hill Cemetery in Rome, Floyd County, Georgia

Start with What You Know and Work Backward

W e’ve discussed the importance of beginning your research with what you know and with searches for information, sources, and evidence found at your family home or in the possession of other family members. When you hit a “brick wall” in your research, go back and review in detail all the information you have acquired. Reread everything in chronological sequence and look at the total picture of your subject’s life. I personally found myself doing this again and again in the course of my research on my great-grandmother, and ultimately the pieces fell into place. Let’s examine my research process in this case study.

Family Tradition

The family story (or tradition) said that my great-grandmother Penelope died the morning after the birth of one of my mother’s sisters. My aunt, Carolyn Penelope Weatherly, was born on 12 January 1914, in Green Berry and Penelope’s home on Broad Street in Rome. She was shown to Penelope, who was ill at the time. Penelope asked that the child be named after her, and so she was given the name of Penelope, which she used all her life. Starting with that story, I began my search for records.

The first task was to ask questions of my mother and her sisters. I initially interviewed them together at a holiday get-together, and subsequently individually. By that time, my grandmother was deceased and only two of her siblings, two sisters, were still living. I spoke with them by telephone to gather as much oral information as possible. These discussions provided some basic details to get me started, and I also was given my great-grandmother’s Bible and several letters in her handwriting. I next began to identify types of records that might have been created.

Start with Death-Related Records

It is important to begin at the end of a person’s life for records created at or near the time of death. Obituaries and death certificates, if you can find them, can reveal clues to primary and/or secondary information sources. While some Georgia counties and cities did maintain birth and death records from earlier years, it was not until 1919 that Georgia required the registration of all births and deaths in the state. Floyd County and Rome did not create these records until 1919, and so there was no death certificate for Ansibelle Penelope Swords Holder.

I next contacted the Genealogy Department of the Sarah Hightower Regional Library in Rome to determine if they might have microfilm of the local newspapers from 1914 from which an obituary could be obtained. I was informed that their microfilm of the Rome Herald-Tribune was incomplete, and that 1914 was one of the years that they did not have.

Locate a Marriage Record

My next step was to contact the Floyd County Courthouse in Rome to try to obtain a marriage record for Green Berry and Penelope. I hoped the marriage license might provide the bride’s parents’ names, her age, and/or her place of residence. The response from the courthouse included a document that showed Greenberry [sic] Holder marrying a Miss A. P. Sanders (or Sauders) on 27 December 1866 (see Figure 1). This was a surprise. Could Penelope have been married before? I considered five possibilities:

Penelope was supposedly born in 1842 and married Green Berry in 1866. She would have been 24 years old, a somewhat advanced age for a woman to be married at that time.

Penelope was supposedly born in 1842 and married Green Berry in 1866. She would have been 24 years old, a somewhat advanced age for a woman to be married at that time. The marriage occurred not long after the U.S. Civil War ended and, considering Penelope’s age, it might have been possible that she had been married before to a man whose surname was Sanders or Sauders and that she had been widowed as a result of the war.

The marriage occurred not long after the U.S. Civil War ended and, considering Penelope’s age, it might have been possible that she had been married before to a man whose surname was Sanders or Sauders and that she had been widowed as a result of the war. The entry from the Floyd County Marriage Book (vol. A, page 347, # 1359) clearly identifies her as Miss A. P. Sanders, indicating an unmarried woman.

The entry from the Floyd County Marriage Book (vol. A, page 347, # 1359) clearly identifies her as Miss A. P. Sanders, indicating an unmarried woman. Was it possible that the clerk entering the record on 15 April 1868 made an error in reading or transcribing the name?

Was it possible that the clerk entering the record on 15 April 1868 made an error in reading or transcribing the name? The couple’s first child, Edward Ernest Holder, was born on 28 January 1868. The couple was therefore most probably married before April of 1867.

The couple’s first child, Edward Ernest Holder, was born on 28 January 1868. The couple was therefore most probably married before April of 1867.

Figure 1. Marriage record from the Floyd County, Georgia, marriage book

I contacted the Floyd County Courthouse again to determine if there was any record of another marriage for Ansibelle Penelope Swords on file or any record of a divorce for her from a man named Sanders. I was informed that no such records were found.

Check the Census Records

Based on the information I had found so far, I decided to check in the U.S. federal census records for Georgia for various years. Knowing that Green Berry married in 1866, I checked the 1870 census for his entry. I found a listing for him in Subdivision 141 of Floyd County, Georgia, along with his wife, “Arcybelle P.,” and sons “Edward W.,” age 2, and “Willis I.,” age 3/12 years (3 months). This gave me four important clues:

“Arcybelle P.” (another misspelling) certainly agreed with the “A. P.” initials on the marriage record, and the age of the first son certainly agreed.

“Arcybelle P.” (another misspelling) certainly agreed with the “A. P.” initials on the marriage record, and the age of the first son certainly agreed. “Arzybell P.” is listed as having been born in Alabama.

“Arzybell P.” is listed as having been born in Alabama. I was not concerned about the wrong middle initial for Edward, which should have been “E.” It also did not concern me too much that the forename of the second son was really William Ira Holder, and not “Willis.” The original 1870 census documents were transcribed twice and the last copy was sent to Washington, D.C. This is the copy from which the microfilm was created (and later the digitized images were created from that film). I therefore surmised that the spelling of “Arcybelle” and the two name errors for the sons could point to either enumerator spelling errors or transcription errors.

I was not concerned about the wrong middle initial for Edward, which should have been “E.” It also did not concern me too much that the forename of the second son was really William Ira Holder, and not “Willis.” The original 1870 census documents were transcribed twice and the last copy was sent to Washington, D.C. This is the copy from which the microfilm was created (and later the digitized images were created from that film). I therefore surmised that the spelling of “Arcybelle” and the two name errors for the sons could point to either enumerator spelling errors or transcription errors. There was no child in the household with the surname of Sanders (or Sauder).

There was no child in the household with the surname of Sanders (or Sauder).

The 1880 census showed Green B. Holder in Enumeration District 11 of Floyd County, age 34. His wife is recorded as “Ansabell,” age 34, and nine children are listed: Edward (son – 13 years old), Willis (son – 11), Scott T. (son – 9), Ida (daughter – 7), Annie (daughter – 5), Luther (son – 4), Ella (daughter – 3), Brisco (son – 1), and Emma (daughter – 4/12). This census shows that “Ansabell” and her parents were all born in Georgia.

The next available federal census, in 1900, shows Green B. Holder in Supervisor’s District 7, Enumeration District 153, Lindale District in Floyd County, with his wife, “Nancy B.,” [sic, Ansibelle] and the following children: William I. (born November 1869), Ida L. (July 1872), Anna L. (April 1874), Luther M. (July 1875), Ella E. (October 1876), Emma E. (December 1879), Charles W. (May 1881), Nita M. (June 1882), and Lizze B. [sic, Elizabeth] (July 1885). Note that family tradition always indicated that the last child, my grandmother Elizabeth Holder, was called by the nickname she gave herself as a baby, “Lizzie Bep.” This census indicates that “Nancy B.” and her parents were all born in Georgia.

The 1910 census, the last enumeration before both Green Berry and Penelope died in 1914, shows them at 808 South Broad Street, Supervisor’s District 7, Enumeration District 69, 5th Ward, the Rome Militia District. Green B. Holder is 65, wife “Annie” is 67, and living with them are three of their daughters: Ida (age 32), Anna (28), and Emma (26). A further clue indicates that “Annie” was born in Alabama, and that both of her parents were born in South Carolina.

Please note that both the 1870 and 1910 censuses show Penelope born in Alabama and her parents born in South Carolina. The 1880 and 1900 censuses show her and her parents all born in Georgia. This contradictory information is confusing, but it also points to South Carolina as a place to ultimately search for her parents, once they are identified.

It was now time to move backward from the marriage certificate to try to identify and connect Ansibelle Penelope to her parents and family. I next went looking through 1860 federal census indexes in Georgia, looking for the surname of Swords. I located a printed index of Cobb County, Georgia, for that year and it pointed me toward the census of the First District, Roswell Post Office, in Cobb County. A detail of the census page is shown in Figure 2. There I found the J. N. Swords family, including Penelope at age 18—the correct age if she was born in 1842 as indicated on her gravestone. I now had the names of her parents, J. N. and Rebecca Chapman Swords, and evidence inferring that both of them were born in South Carolina, and evidence inferring that Penelope was born in Alabama.

Figure 2. Detail from the 1860 U.S. federal census, Cobb County, Georgia

Make a Very Successful Genealogy Trip

I felt that I had done just about all the research possible from the comfort of home and with the remote assistance of the genealogical and history collections in libraries and archives and the Floyd County Courthouse. It was time to make a road trip. I gathered all my information about Green Berry Holder, Ansibelle Penelope Swords, and their children, organized it, and prepared a research plan. I did my preliminary research on the Internet, contacted the genealogy librarian at the Sarah Hightower Regional Library, and made contacts with the Rome Municipal Cemetery Department and the Northwest Georgia Genealogical Society for appointments to meet with people on site. Two months later, in July 1997, I drove from my home in Tampa, Florida, to Rome, Georgia, for what would be one of the most successful research trips of my life.

The library in Rome proved to contain a wealth of information for my research. The genealogy librarian there at the time, Gwen Billingsly, was an outstanding help to me. City directories in the library’s collection helped me place Green Berry and his sons at specific addresses in Rome. The papers of George Magruder Battey, the local historian, contained correspondence with some of the Holder daughters and with others that discussed the town’s history and my great-grandfather’s role in the community. Local histories, both printed and typewritten one-of-a-kind manuscripts, also assisted in my quest. The microfilm collection of the Rome Herald-Tribune was incomplete, as I had learned before. However, Ms. Billingsly knew that the missing years’ original newspapers were stored in the county school district administration’s records retention facility. Apparently the library had run out of funds to microfilm all the years of publication. She contacted the administrator there and arranged for me to visit and examine these original newspapers

When I arrived at the records retention facility, I was warmly greeted and led through a warehouse to the area where the complete, leather-bound volumes of the 1908, 1909, 1913, and 1914 newspapers were stored. The year 1914 was the one of most interest to me, since my great-grandmother died on 13 January 1914 and my great-grandfather followed her in death on 18 June 1914. It was easy to locate their obituaries and, working with the fragile newsprint and without the benefit of a photocopier (or a digital camera at that time), I carefully transcribed both obituaries. (These newspapers were subsequently microfilmed, by the way.) There were, of course, many clues in my great-grandmother’s obituary in the Rome Herald-Tribune, Rome, Georgia, on Wednesday morning, 14 January 1914, page 1, which reads as follows:

Mrs. G.B. Holder, aged 71 years, an old and honored resident of Rome, died Tuesday night at 11:10 at the family residence, 808 South Broad Street, after a brief illness of pneumonia. The deceased was born at Rock Creek, Alabama, in 1848. She married in 1867, G.B. Holder, of this city, and has since resided in Rome. Her husband is a prominent business man of the county. Mrs. Holder was a member of the Primitive Baptist church and always took an active part in the church work.

She is survived by 11 children, five sons and six daughters. The sons are Ed Holder, Will Holder,

Scott Holder, Brisco Holder and Charlie Holder. The daughters are Misses Isa [sic, sIda] Holder, Anna Holder and Emma Holder, Mrs. A.D. Starnes, Mrs. Walton Weatherly and Mrs. Wyatt Foster. She is also survived by three sisters, Mrs. Cal Menton and Mrs. Davis of Alabama, and Mrs. George Black of Cedartown.

The funeral services will be conducted from the residence at 3 o’clock this afternoon, the Rev. J. W. Cooper officiating. Interment will follow in Myrtle Hill cemetery.

The following pall-bearers will meet at 2:30 o’clock at Daniels Furniture Company: Honorary, J.G. Pollock, B.F. Griffin, Capt. J. H. May, M.W. Formby, H.V. Rambo, Tom Sanford. Active: J.M. Yarbrough, G.G. Burkhalter, Sanford Moore, W.A. Long, Dr. R.M. Harbin, C.B. Geotchius.

The most significant facts for my research beyond my great-grandmother into her siblings, parents, and her other ancestors were the names of her three surviving sisters. First, I discounted “Mrs. Davis of Alabama” as being nearly impossible to locate. However, I did search the Alabama census records for Mrs. Cal Menton. I began searching the Menton surname and for a man whose forename might have been Calvin, Calvert, Calbert, Calhoon, and other variations, all without success. I next did the same search with different spellings of the surname, including Minton. I had made the assumption that “Cal” was a man’s name. I soon realized that the custom of the time was that a married woman used her husband’s first and last names, and that a widow used her own first name and the surname of her husband. Mrs. Cal Menton, as it later turned out, was the widow of William Martin Minton. “Cal” was a nickname used for Caroline. As a widow, she went by the name of Mrs. Caroline Minton. When I later located her, it turned out that she was the daughter listed variously as L. C. Swords or Lydia Swords; her full maiden name was Lydia Caroline Swords. This is an example of why it is important to know first and middle names, as well as nicknames, and to search every variation you can conceive.

“Mrs. George Black of Cedartown,” a town south of Rome in Polk County, Georgia, was easier to locate. I visited Cedartown, the county seat of Polk County, to search for a marriage record and probate records for Mr. and Mrs. Black, but without success. I returned to Rome, the county seat of Floyd County, to perform similar searches. I examined the marriage book in which Green Berry’s marriage was recorded. Just beneath that record was another for the same date in December 1866, this one for George Black and Martha Ann Swords. The surprise was that the two sisters had been married the same day. Perhaps it was a double ceremony. A search in the Floyd County probate records also revealed a probate packet for George S. Black that specifically mentioned his wife, Martha.

Take Another Look at Census Records

I went back to look at the census records again. In the 1860 census, two other daughters of J. N. and Rebecca Swords are listed: M. A. Swords (age 20) and L. C. Swords (age 17).

Next I went to the 1850 census and, based on the 1860 census and the ages of the children born in Alabama, I worked with census indexes. I found the family in the 1850 census in the 27th District, Cherokee County, Alabama. The parents were listed as John N. Swords and his wife, Rebecca. Among the children listed, I found a seven-year-old daughter named Lydia, an eight-year-old daughter named Nancy, and a ten-year-old daughter named Martha, all of whom had been born in Alabama (see Figure 3). I’d found the right place, the right people, and the right person. The name “Nancy” in the 1850 census corresponded with the same name in the 1900 census and was certainly similar to “Ansabell” and “Annie” in other censuses, and the names of the sisters were correct. I had the correct family and the correct individuals.

Figure 3. Detail from the 1850 U.S. federal census, Cobb County, Georgia

Contact Other Courthouses

I still had that nagging question about the surname of Sanders (or Sauders) that was on the document in the Floyd County Marriage Book. I considered that it was possible that Ansibelle Penelope Swords might have been married prior to her 1867 marriage to Green Berry. Therefore, I wrote the courthouses in the counties of Cobb and Floyd, and the counties in between—Bartow, Cherokee, Gordon, Paulding, Pickens, and Polk—to request that they check the bride indexes in their marriage books between 1860 and 1867 for a woman with the surname of Swords and a forename of Ansibelle and/or Penelope, or with the initials A. P. All the responses indicated that no such names appeared in their marriage indexes. Remember that sometimes not finding something you are looking for may be as good as finding something.

Other Information Discovered Along the Way

The appointment with the cemetery administrator in Rome reconfirmed dates of death and interment for Penelope Swords Holder in the Myrtle Hill Cemetery Interments ledger. The ledger is a daily record of the interments in that cemetery. It usually lists the date, name, and lot and plot where the remains were placed. It typically also includes the cause of death and, in the case of my great-grandmother, the entry recorded the cause of her death as pneumonia. There also was an entry for Green Berry Holder in June of that year.

I also learned that their daughter, Emma Dale Holder, sold three spaces in the family cemetery lot in 1956 to the owners of the adjacent lot, the family of George and Martha Black. It turns out that Ansibelle Penelope Swords Holder and her sister Martha Ann Swords Black were buried toe-to-toe in the cemetery.

I obtained the marriage entries from the Floyd County Courthouse for all of my great-grandparents’ children who married there, as well as copies of death certificates for eight of their children. I located the graves of all eight of those children, including Edward E. Holder, who was widowed and then remarried, and who was buried in a cemetery other than the one in which his original, pre-inscribed tombstone had been placed.

In the Floyd County Courthouse, a clerk’s preliminary search of land and property records showed more than 38 pages of entries in their grantor and grantee deed indexes for G. B. Holder, A. P. Holder, Ansibelle Penelope Holder, Penelope Holder, and for their sons, Edward, William, Scott, and Luther Holder. I have reserved an entire future trip to concentrate specifically on the actual land and property entries. I then plan to locate each property on county maps and discover what they can reveal to me.

Finally, after all of the census research, it dawned on me where the nickname for my great-aunt, Ella Edna Holder, had come from. My mother and her sisters had always referred to her as “Little Annie.” I now learned that she earned that family nickname because she always scurried around taking care of her siblings the same way her mother took care of them.

From the clues obtained along the way in my search for Ansibelle Penelope Swords Holder’s family, I was able to significantly expand my knowledge and documentation of the entire family unit’s genealogy. However, the clue that John N. Holder’s and his wife, Rebecca’s, parents were both born in South Carolina carried me back to both their families. In addition, I’ve since been able to locate copious amounts of documentation about John N. Holder’s siblings and their parents, a Revolutionary War soldier named John Holder, and his wife, Eleanor Swancey, both of whom are mentioned in other parts of the book.

My search to learn more about the family has continued. My investigation into the son Brisco Washington Holder has led me from Georgia to locate records of him in five other states and Canada. I located his death certificate in the city of St. Louis, Missouri, and his burial spot in St. Louis County, Missouri. I arranged for the placement of a gravestone on his grave.

Genealogy research has taken me through an exciting adventure of discovery. Ansibelle Penelope Swords Holder presented a formidable brick wall but, using a variety of record types and some well thought-out methodology, more doors were opened.

Penelope was supposedly born in 1842 and married Green Berry in 1866. She would have been 24 years old, a somewhat advanced age for a woman to be married at that time.

Penelope was supposedly born in 1842 and married Green Berry in 1866. She would have been 24 years old, a somewhat advanced age for a woman to be married at that time. The marriage occurred not long after the U.S. Civil War ended and, considering Penelope’s age, it might have been possible that she had been married before to a man whose surname was Sanders or Sauders and that she had been widowed as a result of the war.

The marriage occurred not long after the U.S. Civil War ended and, considering Penelope’s age, it might have been possible that she had been married before to a man whose surname was Sanders or Sauders and that she had been widowed as a result of the war. The entry from the Floyd County Marriage Book (vol. A, page 347, # 1359) clearly identifies her as Miss A. P. Sanders, indicating an unmarried woman.

The entry from the Floyd County Marriage Book (vol. A, page 347, # 1359) clearly identifies her as Miss A. P. Sanders, indicating an unmarried woman. Was it possible that the clerk entering the record on 15 April 1868 made an error in reading or transcribing the name?

Was it possible that the clerk entering the record on 15 April 1868 made an error in reading or transcribing the name? The couple’s first child, Edward Ernest Holder, was born on 28 January 1868. The couple was therefore most probably married before April of 1867.

The couple’s first child, Edward Ernest Holder, was born on 28 January 1868. The couple was therefore most probably married before April of 1867. “Arcybelle P.” (another misspelling) certainly agreed with the “A. P.” initials on the marriage record, and the age of the first son certainly agreed.

“Arcybelle P.” (another misspelling) certainly agreed with the “A. P.” initials on the marriage record, and the age of the first son certainly agreed. “Arzybell P.” is listed as having been born in Alabama.

“Arzybell P.” is listed as having been born in Alabama. I was not concerned about the wrong middle initial for Edward, which should have been “E.” It also did not concern me too much that the forename of the second son was really William Ira Holder, and not “Willis.” The original 1870 census documents were transcribed twice and the last copy was sent to Washington, D.C. This is the copy from which the microfilm was created (and later the digitized images were created from that film). I therefore surmised that the spelling of “Arcybelle” and the two name errors for the sons could point to either enumerator spelling errors or transcription errors.

I was not concerned about the wrong middle initial for Edward, which should have been “E.” It also did not concern me too much that the forename of the second son was really William Ira Holder, and not “Willis.” The original 1870 census documents were transcribed twice and the last copy was sent to Washington, D.C. This is the copy from which the microfilm was created (and later the digitized images were created from that film). I therefore surmised that the spelling of “Arcybelle” and the two name errors for the sons could point to either enumerator spelling errors or transcription errors. There was no child in the household with the surname of Sanders (or Sauder).

There was no child in the household with the surname of Sanders (or Sauder).