6

Extend Your Research with Advanced Record Types

HOW TO…

- Use religious records to trace your family

- Obtain and analyze mortuary and funeral home records

- Read between the lines in obituaries

- Discover the wealth of information in cemetery records

- Get inside your ancestor’s mind using wills and probate records

- Use historical newspapers to learn about your ancestor’s life events

- Consider other institutional records

You’ve learned a great deal about your family so far by locating and using home sources, birth, marriage, and death records, and census resources. Along the way, you also have built a foundation for all of your future genealogical research. You now know how important it is to place your family into context, to conduct scholarly research, to analyze every piece of data you uncover, and to properly document your source materials.

You’ve made a lot of progress so far, but the records we’ve discussed so far have only just begun to scratch the surface of your family’s rich history. There literally are hundreds of different documents and record types that may contain information of value in documenting your forebears’ lives.

This chapter discusses some of the more important documentary evidence associated with your ancestor, their religion, and information sources concerned with the end of his or her life. They can provide a treasure trove of information and clues for you. You just need to know where to look, how to access the records, and how to properly analyze them. Remember that not everything is available on the Internet. Most records are stored in courthouses, libraries and archives, churches, government offices, and many other places. You will always need to combine traditional research with electronic research on the Internet and in databases. You will learn to apply your critical thinking skills to the evidence and formulate reasonable hypotheses, sometimes circumventing the “brick walls” that we all invariably encounter.

Use Religious Records

Religious records are those that relate to a church or some similar established religious institution. Organized religion has provided a source for scholarly philosophical and theological study and writing for many centuries. Documentation reaches far back into human history. Religious groups also have variously maintained documents concerning their operations, administration, and membership. As a result, religious records of many types can provide rich genealogical details and clues to other types of records.

There are a number of challenges you will face in your search for and investigation into these ecclesiastical records. Let’s discuss these challenges first, and then we’ll explore some of the types of records you might expect to find.

Locate the Right Institution

It is an easy task to contact the place of worship for yourself, your parents, and your siblings. The knowledge of the religious affiliation and where the family members attend worship services is pretty easy to come by. However, as we move backward in time, this information may become obscured. You may make the assumption that your ancestors belonged to the same religious denomination as your family does today, and you may be making a terrible error.

Not every member of a family necessarily belongs to the same religious group. My maternal grandmother’s family provides an excellent example. Her father belonged to the Presbyterian Church and her mother to a Primitive Baptist congregation. Among their six sons and six daughters, I have found them to be members of two Presbyterian, three Baptist, one Methodist, and one Christian Science churches. In addition, some of the people changed churches. Most notable was the entry I found in the membership roll of the First Presbyterian Church of Rome, Georgia, dated 31 October 1926, for one of my great-aunts. It read, “Seen entering Christian Science Church” and her name was lined out. That clue pointed me to the Church of Christ, Scientist, where I learned that she had formally become a member of its congregation.

In some cases, prior to or upon marriage, one spouse may change his or her religious affiliation to that of the other spouse’s affiliation. Many religions want to see children of a marital union raised in their faith, and formal religious instruction and conversion is common.

Determining the religion of an ancestor or other family member is an important part of your research because there may be any number of records to provide more information for your research and pointers to other records. You cannot assume that everyone who lived in England or Wales was a member of the Church of England, that everyone who lived in Scotland was a member of the Church of Scotland, or that everyone who lived in Ireland was either Catholic or Protestant. In all these areas, other religious congregations were common, including Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Quaker, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Hindu, and Buddhist. You also cannot assume that the only religions in Germany were Catholicism and Lutheranism. You will find Mennonite, Baptist, Anabaptist, Methodist, Seventh-day Adventist, and Orthodox churches, as well as Muslim, Buddhist, Sikh, Hindu, and Bahá’í Faith groups.

Look for clues to the religion of a person in the name of the clergy who performed marriage ceremonies for the person and the spouse, for the person’s parents, and for any siblings. Clergy names are typically found on marriage certificates created by churches, such as the one shown in Figure 6-1, and on many marriage licenses filed at government offices after the marriage ceremony has taken place. These documents are referred to as “marriage returns,” as they have been returned to the courthouse or civil registration office to be registered as complete. Look, too, at obituaries for the names of officiating clergy at funerals and memorial services. It is often easy to determine the religious affiliation of the clergyperson and the organization to which he or she was attached in local historical records and city directories. This can provide an important link to membership rolls and to records of life events associated with the congregation.

FIGURE 6-1 Marriage certificate issued by a church showing the name of the officiating clergy

The religious affiliation provides one level of information. However, your job is to determine the right institution to which your ancestor belonged. If the community in which he or she lived has multiple groups of the same denomination, you may have to contact or visit each one in order to determine if your ancestor was a member of one of those congregations. Depending on the time period in which your ancestor lived in the area, you may also need to research local histories to determine which specific religious groups existed at the time. Your best strategy, however, may be to start with the congregation located closest geographically to where your ancestor or family lived, and work outward. You may also have to escalate your search to an administrative or similar jurisdictional level to locate records for defunct congregations. For example, records for the congregation of a Catholic church that merged with another may have been transferred to the latter church. Alternatively, the records may have been moved to another diocese location or to some other place. Be prepared to escalate your inquiry for a defunct church’s records to a higher administrative office. This means doing a little more research into the structure of the religion and its jurisdictional structure.

Determine What Records the Institution Might Have Created

Once you have determined the religious affiliation of your ancestor, it is important to learn something about the organization. Some groups are meticulous about documenting their organizational affairs and their membership information, while others are less inclined. The Quakers and the Catholic Church, for example, generally maintain thorough documentation of the church business and have created detailed documents about each member, including records for birth, baptism, christening, marriage, death, other sacramental and personal events, and even tithing. Other denominations or congregations may not have maintained such comprehensive records, and the documents that survive can often be far less detailed or revealing.

Invest some time in learning about the history of the denomination to which your ancestor belonged and types of records it may have created at the time your ancestor was a member. This will give you a foundation for your research. You will begin to learn what types of records to request when you make contact with the particular church or organization, where they were created and by whom, what information is likely to be contained in them, and where they were kept. A good starting point is a search in Wikipedia at www.wikipedia.com, followed by a web search for the name of the religion.

Locate the Records Today

Your most immediate consideration is where to locate the records now. Congregations sometimes merge with one another, or a congregation may find it can no longer sustain itself financially, and therefore dissolves. What happens to the records?

Your understanding of the history and organization of the denomination can go a long way in helping you locate records. Your study will also help you identify the types of records that were created. For example, some Christian denominations may mark a person’s first communion with a ceremony and issue a certificate such as the one shown in Figure 6-2, while others may only record the event in membership records. While an existing church location may have all of its records dating back to its founding, those records may not necessarily be located on-site at that church. They may be stored in a rectory, parsonage, or vicarage. Records may have been moved to another church of the same denomination in the area, to a central parish or diocesan office, to a regional or national level administrative office, or to a storage site.

FIGURE 6-2 Certificate of a first communion

A good strategy for determining the location of historical records is to contact the clergy or secretary at the specific house of worship. Having learned what records might have been created, you can ask about their availability and request access to or copies of them. If the records have been moved or sent elsewhere, ask for the name and address of a contact and then follow that lead.

If a congregation no longer exists or you can’t find it, contact the local public library and any academic libraries in the area and ask the reference department to assist you in tracing the group and its records. The local, county, state, or provincial genealogical and historical societies are additional resources you should enlist in your research. Their in-depth knowledge of the area and religious groups can be invaluable. Indeed, they may have copied or transcribed indexes, and some ecclesiastical records may even have come into their possession. Again, don’t overlook making contact with a higher administrative area of the religious organization. The personnel should be able to provide you with details of the group’s history and of the fate of a “missing” congregation’s records.

Parish registers in England, Wales, Scotland, and the Channel Islands were in danger of damage or loss during World War II. German bombing raids often focused on churches as targets. Many of the original parish records were evacuated from the churches to other places of safety. Many of these were ceded to archives or universities for permanent safekeeping. Locating the parish registers is a key to locating an ancestor’s christening, marriage, or burial record prior to the implementation of civil registration in England and Wales in 1837 and in Scotland in 1855. An excellent resource for determining which parish registers exist, the years they cover, and their location is the book The Phillimore Atlas & Index of Parish Registers, 3rd edition, by Cecil R. Humphery-Smith (The History Press, 2003). The book contains detailed maps of every county and its parishes, as well as a detailed table of current locations of the records.

Parish clergy in the Church of England were required from the time of Elizabeth I to transcribe the christening, marriage, and burial entries from their parish registers and send a copy to their bishop. Many of these Bishop’s Transcripts are now in the possession of the County Record Office (CRO) in the county where the parish was located at the time. Please note that county boundaries have changed over the centuries. You will want to research histories and historical maps to determine the correct CRO from which to seek information.

Gain Access to the Records

Another challenge can be gaining access to or obtaining copies of the ecclesiastical records you want. Religious groups are, in effect, private organizations and have a right and an obligation to protect their privacy and that of their members. Most are willing to help you locate information about your ancestors and family members, particularly if you do most of the work. Remember that not all church office personnel are paid employees; some are simply members volunteering their time. Not all members of the office staff, and even members of the clergy, know what records they have and what is in them. The old books and papers in their offices may just be gathering dust in a closet or file cabinet. Few of these materials are indexed, such as the document shown in Figure 6-3, which was found among a sheaf of loose papers tucked into a cardboard box in a church office cabinet. It often takes a considerable effort to go through such documents and locate information that may relate to your family.

FIGURE 6-3 This loose document from the minutes of a church session commemorating the life and service of a member was found in a box, and it was never indexed.

Be prepared to offer to help the person you contact in the church office. You may have to describe the types of record you are seeking and where they might be located. Any reluctance you encounter may be a result of the person’s lack of knowledge and experience, lack of time, the cost of making and mailing copies for you, or some other reason. Be kind, patient, and friendly, and offer all the help you can. Be prepared to reimburse all the expenses and to make a donation to the congregation.

Interpret, Evaluate, and Place the Records into Perspective

Once you obtain the documents you want, your next step is to carefully read and review them. Interpretation can be a real challenge, particularly if the handwriting is poor, the copies are dim or illegible, or the document is written in a language you do not understand. Many church records are written in Latin, particularly those of the Catholic Church and those of the early Church of England. You may encounter Jewish documents written in Hebrew or other languages, Russian Orthodox Church documents written using the Cyrillic alphabet, and any number of foreign languages and dialects. Old English script and German Fraktur both resemble calligraphy and their character embellishments can be particularly difficult to read. Other older or archaic handwritten materials may be difficult or nearly impossible to decipher. You will want to consider obtaining books on the subject of paleography (the study of ancient writings and inscriptions; also spelled palaeography) and using the skills or services of interpreters. Two particularly good books are Palaeography for Family and Local Historians (2nd Revised edition) by Hilary Marshall (The History Press, 2010) and Reading Early American Handwriting by Kip Sperry (Genealogical Publishing Company, 1998; reprint 2008).

As with the other documentary evidence you have obtained, be prepared to evaluate the contents of the documents. Consider the information provided and use it to add to the overall chronological picture you are constructing of your ancestor or family member. Let’s now look at specific ecclesiastical records.

Consider a Variety of Religious Records

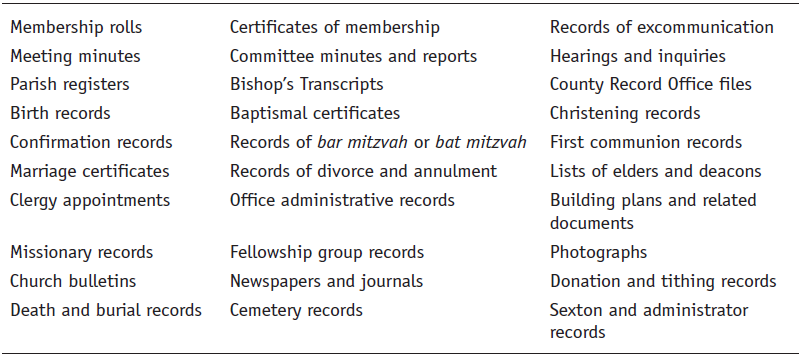

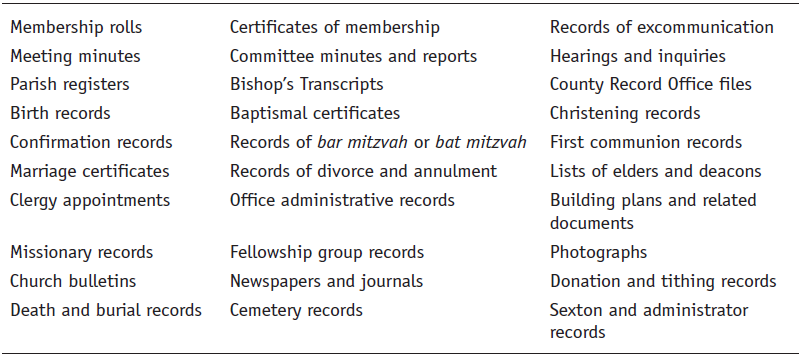

Your research will present you with a vast array of potential information sources from religious organizations. The following is a list of some of the records you may encounter. Some are more common than others, and the list certainly will vary depending on denomination, time period, and the specific congregation.

Any of these documents can provide clues about your ancestor or family member’s life. Don’t overlook the fact that membership records and meeting minutes also may record the previous place of membership for an individual. I was successful in tracing my maternal grandfather from the church in which he was a member at the time of his death, back through three other churches in which he was a member, to the church in which he was baptized more than six decades before, all through their membership records. A church bulletin, such as the one shown in Figure 6-4, provided details of the election of another family member to the position of head deacon. And another church had a photograph of a grandfather at the groundbreaking ceremony for a new church building. You never know what you will find in the records of religious organizations.

FIGURE 6-4 Church bulletins share news and may point to other types of church records.

Obtain and Analyze Mortuary and Funeral Home Records

Among some of the most detailed records compiled about a person are those that are created at the time of his or her death. The records of an ancestor or family member whose remains were handled by a mortuary or funeral home may hold many important clues. As with religious records, it is important to do some research in advance to determine whether a mortuary’s services were used and, if so, which mortuary it was.

A mortuary or funeral home performs a variety of functions, and someone usually selects the specific duties desired for the person who is deceased. The activities of the mortuary or funeral home may include providing a simple coffin or fancy casket, embalming and cosmetic preparation, clothing the corpse, writing an obituary, arranging for or conducting services, providing transportation for the family, arranging for interment or cremation, and other, more-specialized services.

Records from a mortuary, funeral home, or crematory relating to the handling of an individual’s arrangements may include many documents. You will usually find a copy of a document, such as a death certificate or coroner’s report, in the file, along with an itemized accounting or invoice for all the services provided. Figure 6-5 shows a page of detail from a funeral home invoice. Information about the selection of a coffin or casket, a burial vault, and other commodities is often included. A mortuary is often called upon to prepare and handle placement of obituaries in newspapers and other media, and that information or a copy of the obituary information may be included in the file. Look for copies of a cemetery deed and a burial permit, depending on the time period, place, and type of burial. These are the more common documents you might find in these files but occasionally you may find others, such as correspondence and photographs.

FIGURE 6-5 Detail page from a funeral home invoice

Mortuaries and funeral homes are private companies and, as such, are not required to provide copies of their business documents to genealogists. An owner or administrator may decline to provide access to you for reasons of business privacy or to protect the confidentiality of family information. They also are not required to retain and preserve records in perpetuity.

Many of these facilities over the years have been sold or have gone out of business. Their records may have been transferred, lost, or destroyed. You may need to work with libraries, archives, and genealogical and/or historical societies to determine the disposition of their records. Some may have been preserved in the special collections of libraries, such as those of several funeral homes in Tampa, Florida, which are now residing in the Special Collections of the University of South Florida Tampa Library. You may need to contact the government offices that handle corporate licensing to determine when a funeral home or mortuary was sold or went out of business. Records of a sale include details of the transfer of ownership and new licensing, and this can point you toward the possible disposition of older records.

Read Between the Lines in Obituaries

We’re all familiar with obituaries and death notices, those announcements of people’s deaths that appear in the newspaper and other media, and also on the Internet. These published gems often contain a wealth of biographical information in condensed form. You can gather a lot from reading what is printed and from reading between the lines.

An obituary is definitely a source of secondary information, derived from one or more persons or documents. You will definitely want to confirm and verify every piece of data listed there. The accuracy of the information included should always be considered questionable because errors can be introduced at any point in the publication process. The informant for the information may or may not be a knowledgeable family member, or the person may be under the stress of the occasion and provide inaccurate details. The person who takes down the information may introduce an error, a newspaper employee may transcribe something incorrectly, and an editor may miss a typographical error.

Some of the information and clues you can look for in obituaries include the following:

- Name and age of the deceased

- Date, location, and sometimes cause of death

- Place of residence

- Names of parents and siblings

- Names and/or numbers of children and grandchildren

- Places of residence of living relatives

- Names of and notes about deceased relatives

- Where and when deceased was born

- When deceased left his/her native land, perhaps even the port of entry and date

- Naturalization date and location

- Place(s) where deceased was educated

- Date(s) and location(s) of marriage(s), and name of spouse(es) (sometimes maiden names)

- Religious affiliation and name of congregation

- Military service information (branch, rank, dates served, medals, and awards)

- Place(s) of employment

- Public office(s) held

- Organizations to which he/she belonged

- Awards received

- Events in which he/she participated

- Name and address of funeral home, church, or other venue where funeral was to occur

- Date and time of funeral

- Name(s) of officiating clergy

- List of pallbearers

- Date, place, and disposition of remains

- Statement regarding any memorial services

- Directions regarding donations or memorial gifts

I use obituaries as pointers to locate record sources of primary information. I certainly use them to help corroborate other sources of evidence, and to help verify names, dates, and locations of events. They may include the names and locations of other family members, and may identify alternative research paths to get past some of the “dead ends” I may have encountered.

One of my most successful uses of obituaries occurred when researching a great-grandmother. I had tried unsuccessfully for years to trace back and identify her parents. I finally visited the town where she lived in 1997 and was able to access the actual 1914 newspaper in which her obituary had been printed. The obituary included the names of three surviving sisters whose married names I had not known. Two of the three were dead ends, but records for the third sister and her husband were easily located. I transferred my research attention to that sister and pretty quickly was able to identify and locate the parents’ records. I then used a will to “connect downward” and prove that my great-grandmother was one of their children. Suddenly the doors opened and, within a matter of months, I traced my lineage back to a great-great-great-grandfather who had fought in the American Revolution and I obtained copies of his military service and pension records.

Locate and Delve into Cemetery Records

Most people’s perception is that a cemetery is a lonely place, devoid of any activity other than the interment of remains and the visits by families and friends of those who have passed before. However, if you have ever participated in the process of making arrangements for a family member, spouse or partner, or a friend, you know that there can be a lot of paperwork involved. And where there is paperwork, there are pieces of potentially valuable genealogical evidence. Some of these materials are accessible to you, the researcher, and others are not. However, let’s examine the processes involved with handling the death of an individual and the documentation that may have been created.

Cemeteries are much more than graveyards. They are representations in a location of the society, culture, architecture, and the sense of the community. Many genealogists and family historians arrive at a cemetery, wander around looking for gravestones, copy down the names and dates, perhaps take a few photographs, and then leave, thinking they have found all there is to be found. In many cases, they have merely drifted past what might have been a treasure trove.

A marker may have been installed in a place in which the decedent was not interred. these markers are known as cenotaphs. In other cases, a marker may have been installed at an intended gravesite, and a person may not have been buried there. Look for the absence of a death date, and always check with the cemetery office or administrator to confirm that an interment did or did not take place.

It is important to know that a tombstone or other type of marker isn’t necessarily the only record to be found in or associated with a cemetery. You also should recognize that these memorial markers are not necessarily accurate sources of primary information. That is because the markers are not always created at or near the time of death, and incorrect information may have been provided and/or inscribed. While a marker may have been placed within a short time of the interment, you cannot always determine if that is the case. In other cases, a marker may have been installed in a place in which the decedent was not interred. These markers are known as cenotaphs. Also, understand that the information carved on a tombstone or cast in a metal marker is actually a transcription of data provided, and that one or more errors may have been made. For example, there is a granite marker in an old cemetery in St. Marys, Georgia, on which an incorrect name was carved. Rather than replace the entire stone, the stonecutter used a composite stone paste to fill in the incorrect letter. After the paste set, the correct letter was carved. Unfortunately, the flaw is still visible on the stone (see Figure 6-6). I have seen many “tombstone typos” over the decades.

FIGURE 6-6 Grave marker showing a stonecutter’s error and correction

Someone or some organization owns and/or is responsible for a cemetery. A visit to the local city government office that issues burial permits, to the office that handles land and tax records, or to the closest mortuary can usually provide you with the name of the owner or a contact individual. The next step is to make contact with the person or agency responsible for the maintenance of the cemetery. That may be an administrator or sexton, and this contact may yield important information.

Cemeteries typically consist of lots that are subdivided into plots into which persons’ remains are interred. Someone owns the lot and has authorized the burials there. If a government is involved, there may have been a burial permit or similar document created to allow a grave to be opened and an individual’s remains to be interred. A crematory’s information concerning the commitment of the cremains to a columbarium niche may also be included. Other documents may well have been created, and they may have been given to the cemetery administrator or sexton for inclusion in the cemetery’s files. As a result, making contact with the cemetery may help you obtain copies of documents that are available nowhere else. Let me give you a few examples.

When I was searching for the burial location of my great-grandparents, Green Berry Holder and his wife, Penelope Swords, I knew they were buried in Rome, Georgia, in the Myrtle Hill Cemetery. I contacted the Rome city administrative offices to determine who was responsible for the cemetery’s administration and maintenance. I was directed to the Rome Cemetery Department, which is responsible for five municipal cemeteries. I made a call and spoke with the sexton of Myrtle Hill Cemetery. He was able to quickly pull the records for Green Berry Holder while we were on the telephone and told me the following:

- The date of the original purchase of the cemetery lot

- The identification information of the lot (lot number and location)

- The names of each person buried in the lot, their date of death, their ages, and the dates of their interments

- The date on which two plots in the lot were resold to the owner of an adjacent lot

I also asked about a great-uncle, Edward Holder, whom I believed was also buried in that cemetery. There was, in fact, a joint grave marker for him and his wife, shown in Figure 6-7, although his year of death was missing. I had assumed that he was buried there; however, the sexton told me that only his wife was interred in this cemetery. It turned out that my Great-Uncle Ed actually was buried in another municipal cemetery on the other side of town beside another woman bearing his surname. I learned that he had a second marriage about which neither I nor anyone else in the family was aware.

FIGURE 6-7 Grave marker for the author’s great-uncle, who is buried in another cemetery with his second wife

Based on the information the sexton was able to provide, I had much better details with which to research my family members interred in both of the cemeteries. I also had information about dates of death that I followed to the Floyd County Health Department. There I was able to obtain copies of all the death certificates. I also headed to the county courthouse for a marriage record for my Great-Uncle Ed’s second marriage and to the library to work with microfilmed newspapers, looking for marriage announcements and obituaries. Had I located the obituary of the great-uncle earlier, I would have known he was buried in the other cemetery and that his second wife survived him.

These clues led me to others, including the name of the current owner of the local funeral home that handled most of the family members’ funerals over the decades, to church records in multiple congregations, to land and property records, to wills and estate probate files, and more.

An on-site visit to the cemetery sexton’s office also provided me the opportunity to see the physical files maintained there. My great-grandmother, Penelope Swords Holder, died prior to Georgia’s requirement that counties issue death certificates. However, there were copies of her obituary, a burial permit, and a note to the sexton from my great-grandfather asking that my great-grandmother be buried in a specific plot adjacent to one of their grandchildren. In addition, the sexton checked an ancient interment ledger and found recorded there the cause of death—pneumonia. This was important because, in the absence of a death certificate, the entry confirmed the family account of the cause of her death.

There are other documents that you may find in a cemetery’s office. These include requests for burial, such as the ones shown in Figures 6-8 and 6-9. A burial permit, such as the one shown in Figure 6-10, is often required in order to control and keep track of the interment, and as another source of local tax revenue.

FIGURE 6-8 A request for burial found in a cemetery file

FIGURE 6-9 A cemetery’s form requesting the opening of a grave

FIGURE 6-10 A burial permit from New York, 1867

Transit permits are used to facilitate the movement of human remains from one political jurisdiction to another. Two examples are shown in Figures 6-11 and 6-12. These documents are usually completed in multiple copies. The original document accompanies the body to the place of final interment; the issuing governmental office retains another copy (or coupon); and other copies may be provided to the transportation carrier(s) en route. A transit permit, such as the one shown in Figure 6-11, may contain a significant amount of information about the deceased, including the age, address, cause of death, the names of the physician and coroner, the name of the undertaker, and the mode of transportation.

FIGURE 6-11 This 1903 transit permit contains many details that can be researched.

FIGURE 6-12 This City of New York transit permit includes less information, but it can still provide clues to locating a death certificate and other records.

Some transit permit formats provided very little information, such as the example shown in Figure 6-12. Transit permits were used when shipping bodies of soldiers back home from other locations, and a copy may be found in the mortuary records, in cemetery files, and in surviving military personnel files.

Search for burial and transit permit records in the county or municipal district in which the death occurred. Depending on the location, they may or may not have survived in the issuing governmental office.

Search for Other Death-Related Documents

Death certificates, obituaries, and burial permits are not the only documents relating to death that you may locate that contain genealogical information. Nor are mortuaries, funeral homes, crematoria, and cemeteries the only places to look for these documents.

Table 6-1 includes a number of important documents, data that they may contain, and where you may search for them.

TABLE 6-1 Other Death-Related Documents and Where to Locate Them

Get Inside Your Ancestor’s Mind Using Wills and Probate Records

Wills and probate packets are extremely interesting and revealing collections of records. A person’s last will may be one of the most honest statements about his or her relationships with other family members and friends. The probate packet’s contents may also provide information and insights into the person that you may never find anywhere else.

A person’s last will may be one of the most honest statements about his or her relationships with other family members and friends. Documents included in the probate packet are an estate inventory, lists of debts owed and due, financial reports, and a list of all potential heirs’ names, addresses, and other details.

Understand the Meaning of a Will and Testament

Let’s first discuss some of the terminology. A will is a legal document in which a person specifies the disposition of his or her property after death. The person who makes the will is called the testator, and the will may also be referred to as the last will and testament.

At the time a testator dies, he or she is referred to as the decedent or the deceased. The process of proving a will’s authenticity or validity is called probate, taken from the Latin word probatim or probare, which means “to examine.” The legal body responsible for reviewing and examining materials related to the handling of an estate in the United States is the probate court. From the 13th century until 1857 (with the exception of the period of the Interregnum, 1649–1660) in England and Wales, ecclesiastical courts handled the probate process, and this usually dealt only with nobility and wealthy landowners. The Court of Probate Act 1857 established a civil court, the Principal Probate Registry (today at www.justice.gov.uk/guidance/courts-and-tribunals/courts/probate), was established on 11 January 1858. A Principal Registry which, under the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857, also served the Court for Divorce and Matrimonial Causes, was attached to the Court of Probate in London, together with a number of District Registries throughout England and Wales. Probate law in the United States, Canada, Australia, and certain other countries is based on the English model.

The person appointed by a court to oversee or administer the affairs of the estate during the probate process is known as the executor. Alternatively or in conjunction with an executor, one or more administrators may be appointed.

Historically, the terms “testator” and “testatrix” and “executor” and “executrix” were used to designate the gender of individuals. the former terms indicate a male and the latter terms indicate a female. In modern times, however, most probate courts no longer use the terms “testatrix” and “executrix.” the masculine terms are used to recognize either gender.

Depending on the size of the estate and/or the amount of detail to which the testator went, a will may be a short document or a lengthy one. A will does not need to be drawn up by a lawyer or solicitor; an individual may write his or her own. It is a legal document so long as the testator signs it. Usually, however, it is advisable to have two or more witnesses to the signing of the document. This makes the probate process, or the proving of the will, simpler because it assures that the signature or mark of the testator is genuine.

If the testator decides to change the will after it is made and signed, a new will can be drawn up, signed, and witnessed. Sometimes, if there are minor changes or if there is an expedient required (such as an interim change to a will while an entirely new one is being drawn up), a codicil can be drafted and signed. A codicil is simply a supplement to a will, usually containing an addition or modification to the original will.

Understand the Probate Process

Medieval English law and legal customs influenced laws in the United States, Canada, and Australia. The terms “will” and “testament” originally referred to separate portions of an individual’s estate, and the documents were usually separate documents handled by separate courts. A “will” was used to dispose of one’s real property, or real estate, and the “testament” was used to bequeath personal property. A study of history in the British Isles will reveal that the courts that were used to probate an estate changed over time from ecclesiastical ones to civil courts. In Wales and England, the last will and testament became a single probated entity and this practice spread to other places. If you are researching wills and probate in the British Isles, an understanding of the history of the process, the courts, their jurisdictions, and the documents’ contents in England, Wales, Scotland, and throughout Ireland, respectively, is essential.

In the United States, though, the use of the singular last will and testament document is generally found to be the norm. This is the type of probate process we will explore in this section. Of course, there are exceptions and special circumstances as with any legal documentary process. However, in the interest of clarifying the probate process, let’s focus on a rather straightforward definition.

The person making a will is called the testator. a person appointed by a court | to oversee and perform the activities associated with settling an estate is called the executor or administrator. a minor change or a temporary amendment to a will is called a codicil.

A person’s last will and testament is intended to express his or her wishes for what is to be done with their possessions after death, as illustrated in the case of Isaac Mitchell, whose will is shown in Figures 6-13 and 6-14. In some cases, there are heavy religious overtones to the document. This is perhaps understandable under the circumstances because, at the time this document is written, the testator is giving careful thought, no doubt, to meeting his or her Maker. In many cases, a person’s will may include instructions concerning the disposition of the body, funeral directions, and/or memorial instructions. A will may be revoked through the creation of a new will or through a document known as a codicil. A codicil can be used to revoke and/or amend specific sections of a will without the person having to write an entirely new will. It may also be used to append additional, supplemental instructions to an existing will. In all cases, however, a will or codicil must be signed by the individual and witnessed by at least two other persons. A notary public also sometimes witnesses the document.

FIGURE 6-13 Part one of the will for Isaac Mitchell of Newberry District, South Carolina, taken from the copy transcribed into the county will book

FIGURE 6-14 Signature area of Isaac Mitchell’s will showing names of the witnesses and the probate clerk’s filing reference details

The probate process is a legal procedure intended to certify that a person’s estate is properly disposed of, and the process has changed very little over the past centuries. Where there is a will and it is presented to a court to be proved, there is usually a probate process that takes place. In cases where a person dies without having written or left a will, also known as dying intestate, a court may become involved in making sure the person’s estate is correctly valued, divided, and distributed to appropriate beneficiaries.

While there may be some special conditions of a will or codicil that add additional steps to the process, here’s how a simple probate process works:

- The testator makes his/her will and any subsequent codicil(s).

- The testator dies.

- Someone involved in the testator’s legal affairs or estate presents the will/ codicil(s) to a special court of law called the probate court. The probate court and its judge are concerned with the body of law devoted to processing estates. (Minutes and notes concerning the estate and any probate court proceedings related to the estate are recorded throughout the process and should never be overlooked in your research of the estate.)

- The will/codicil(s) is/are recorded by the probate court. The persons who witnessed the testator’s signature are called upon to testify or attest to, in person or by sworn affidavit, that they witnessed the actual signature to the document(s). This is part of the “proving” of the will—that it is the authentic document on which the testator signed his/her name.

- The probate court assigns an identifying code, usually a number, to the estate and enters it into the court’s records. A probate packet is created for the court into which all documents pertaining to the settlement of the estate are placed. If the will or codicil(s) named one or more persons to act as the executor and/ or administrator of the estate, the probate court issues what is called “letters testamentary.” (If a named executor cannot or will not serve, the court may name another person to act in that capacity.) This document authorizes that person or persons to act on behalf of the estate in conducting business related to settling all claims.

- Potential beneficiaries named in the will/codicil(s) are identified and contacted. If any are deceased, evidence to that effect is obtained, and if the intent of the will indicates that others besides the deceased beneficiaries are to benefit from the estate, they are identified and contacted.

- The executor and/or administrator publishes a series of notices, usually in newspapers circulated in the area where the testator lived, concerning the estate. Persons having claims on or owing obligations to the estate are thereby given notice that they have a specified amount of time to respond.

- The executor and/or administrator conducts an inventory of the estate and prepares a written list of all assets, including personal property, real estate, financial items (cash, investments, loans, and other instruments), and any other materials that might be a part of the estate.

- The executor and/or administrator settles any debts, outstanding claims, or obligations of the estate, and then prepares an adjusted inventory of the deceased’s assets. This document, along with any supporting materials, is submitted to the probate court and becomes a permanent part of the probate packet.

- The probate clerk reviews all the documentation for completeness and submits it to the probate judge for review. The probate court rules that the estate is now ready for distribution to beneficiaries.

- Inheritance taxes and other death duties are paid.

- The estate is divided and distributed and, in many cases, beneficiaries are required to sign a document confirming their receipt of their legacies.

- Following the distribution, the executor and/or administrator prepares a final statement of account and presents it to the probate court.

- The probate court rules that the estate has been properly processed, that all assets have been divided and distributed, and that the estate is closed.

- The probate packet is filed in the records of the probate court.

- The estate is closed.

Special arrangements specified in wills and codicils, such as trusts and long-term bequests, may require additional steps in the process. In some cases, the final settlement of an estate may be deferred for many years until certain conditions are satisfied. A trust, for instance, may require the establishment of a separate legal entity, and the estate may not be settled until a later date. Some people leave wills that skip a generation, perhaps leaving property and/or monies to grandchildren, in which case the estate may not be settled for a generation or more and may require extended administration. In the case of any estate whose settlement extends to multiple years, the executor and/or administrator must prepare annual reports for the probate court. Receipt of these reports is entered into the probate court record and the reports usually are placed into the probate packet.

During the process, the executor and/or administrator typically pays to publish one or more notices in the press as a public notice that all claims against the deceased’s estate should be presented and all debts owed to the estate are to be presented by a specific date. As a result, not only will you be looking in the courthouse and the probate court minutes and files, but you should also be looking in the local newspapers and other publications about the area.

Learn What a Will Can Tell You—Literally and by Implication

Some of the most interesting insights into an individual’s personality and his or her relationships with other family members can be found by looking at probate records. A wife may have been provided for through a trust. It is not unusual in older wills to see a bequest such as, “To my beloved wife, Elizabeth, I leave her the house for her use for her lifetime, after which it is to be sold and proceeds divided between my children.” One of the most amusing bequests I’ve seen was, “I leave my wife, Addie, the bed, her clothes, the ax and the mule.” What a generous husband! However, the husband actually may, at that specific period in time, have legally owned all of his wife’s clothing.

Farther back, you will find that laws sometimes dictated that the eldest son inherited all of the estate, a custom known as the law of primogeniture. Sometimes the eldest son is not listed in the will at all because this law dictated that all real property automatically came to him. In other cases, the eldest son may be named and may be given a double share of the otherwise equally divided estate. In some cases, the testator may apply the rule of primogeniture in order to accomplish some goal, such as keeping an estate from being divided. Ultimogeniture, also known as postremogeniture or junior right, is the tradition of bestowing inheritance to the last-born. Ultimogeniture is much less common than primogeniture.

You will often see a father leave his daughter’s share of his estate to her husband. Why? Often it was because a woman was not allowed to own real property or because it was felt that she could not manage the affairs of the bequest. Sometimes, because a father may have settled a dowry on his daughter when she married, the father’s bequest may be a smaller one than to other, unmarried sisters. It is also possible that a will may leave an unmarried daughter a larger amount than her sisters, in order to make them equal in their overall share of the father’s estate.

A father who did not possess a large estate may have made arrangements for the placement of a son as an apprentice or indentured servant. This was a common means of guaranteeing the care and education of a son when there would not have been enough from the estate to support him. If you find such a statement in a will, investigate court records for the formalization of the arrangement. The guardian became responsible by law for the apprentice or servant.

The absence of a specific child’s name may or may not indicate that he or she is deceased. The omission may indicate that the child has moved elsewhere and has not been heard from for some considerable time. It might also indicate some estrangement, especially if you can determine that the child was, in fact, still alive at the time of the death. Otherwise, it is more likely that the testator would leave an equal part to that child and the court would probably have charged the executor with locating the child. You should investigate each of these possibilities.

It also is possible that, before a will was prepared and signed, an individual may have personally prepared an inventory of his or her possessions or may have engaged the services of an appraiser. Such an inventory would help determine the value of items of real and personal property and therefore facilitate the decisions concerning how to divide them in an equitable fashion.

Examine the Contents of a Probate Packet

You may be amazed at what is or isn’t in a probate packet. Some courts are very meticulous in their maintenance of the packets, in which case you may find vast amounts of documents. Other courts are less thorough, and documents may have been misplaced, incorrectly filed, lost, or even destroyed. It is important when examining probate packets to also review probate court minutes for details. (I once found a missing document from one ancestor’s probate packet filed in the packet of another person’s packet whose estate was heard the same day in court. It had been misfiled.) The most common items found in a probate packet are the following:

- Will These documents are the core of a probate packet and include names of heirs and beneficiaries, and often the relationship to the deceased. Married names of daughters are great clues to tracing lines of descent, and names of other siblings might be located only in these documents.

- Codicil Look for these amendments to a will as part of the probate packet. They also are noted in the minutes of the probate court, along with the judge’s ruling on the validity of the will and the changes included in the codicil. Figure 6-15 shows the first codicil to the will of John Smith of Chelsea, London, making an additional bequest of £1,000 to a neighbor, revoking the bequest of an automobile to his grandson, and calling for the sale of the car and the distribution of the proceeds to a daughter.

FIGURE 6-15 Codicil of John Smith

- Letters testamentary Look for a copy of this document in the probate packet. If it isn’t there, look in court records. The name(s) of the actual executor and/ or administrator may well be different from the person named in the will. You will want to determine the actual person(s) and their relationship (if any) to the deceased. It is important to know if and why the named executor did not serve. Was the person deceased or did he or she decline to serve?

- Inventory or appraisal of the estate The inventory reveals the financial state of the deceased, and this is a good indicator of his/her social status. The inventory of personal property, such as the example shown in Figure 6-16, provides indicators to the person’s lifestyle. The presence of farm equipment and livestock may indicate the person was a farmer; an anvil and metal stock might point to blacksmithing as a profession; hammers, chisels, nails, a level, and other tools may reveal carpentry. In an 18th-century estate inventory, the presence of books indicates education and literacy, and the possession of a great deal of clothing and shoes indicates an elevated social position. The inclusion of slaves, as shown in the inventory in Figure 6-17, is indicative of a position of some wealth. There are many indicators that may direct you to other types of records. You may even find items listed in the inventory that confirm family stories, such as military medals.

FIGURE 6-16 Estate inventory of a wealthy Southern man’s estate file

FIGURE 6-17 Estate inventory dated 1801 that includes the names of slaves

- List of beneficiaries A list of persons named may differ from the list of names in the will. Beneficiaries may be deceased, they may have married and changed names, they may not be locatable, their descendants or spouses may become inheritors, and so on. This list will tell you much about the family.

- Records of an auction Sometimes all or part of an estate was auctioned. Sometimes assets were liquidated to pay bills or to raise money for the surviving family. Auction records reveal much about estate contents and their value. It was common for relatives to participate as bidders/purchasers at an estate auction, and you may find people with the same surname (or maiden name) as the deceased. These may be parents, siblings, or cousins you will want to research.

- Deeds, notes, bills, invoices, and receipts There may be a variety of loose papers in the probate packet that point to other persons. Deed copies point you to land and property records and tax rolls. Names appearing on other papers may connect you to relatives, neighbors, friends, and business associates whose records may open doors for you.

- Guardianship documents Letters and other documents relating to the guardianship and/or custody of widows and minor children are common in probate packets. These can point you to family court documents and minutes that formally document the legal appointment of guardian(s). Figure 6-18 shows a petition for the appointment of a guardian for minor children, and Figure 6-19 shows a combination petition for and granting of guardianship from probate court records in 1911.

FIGURE 6-18 Petition to the court for the appointment of a guardian for minor children

FIGURE 6-19 Combination petition for and granting of guardianship for minor children

- Accounting reports Reports filed with the probate records can provide names of claimants and entities holding estate debts, including names of relatives.

- Final disposition or distribution of the estate A final estate distribution report is of vital importance. You may find the names and addresses of all the beneficiaries, and what they received from the estate. This will ultimately point you to the locations where you will find other records for these persons.

Watch for Clues and Pointers in the Probate Packet

You will almost always find clues and pointers in wills and probate packet documents that point to other types of records. As such, you will soon come to recognize that you must work with these documents in tandem with other documents. Let’s discuss some of these clues and pointers.

A will or probate file may contain information about land and property—including personal property. These references point you to other areas of the courthouse. You may go into land records, tax rolls, court records, and other areas. If any of the assets of the estate were auctioned, check the auction records. These are generally a part of the probate packet too, and may have been entered into the court minutes. Here you may find connections to other relatives of the same surname who came to purchase items.

Guardians are appointed to protect the interests of children (as shown in Figures 6-18 and 6-19) and, in some cases, young widows. Remember that in many locations, if the father died and left a widow and minor children, the children were considered by the courts to be “orphans.” Most often, the guardians appointed by the court were male relatives of the deceased or of the spouse. A different surname of a guardian may be a clue to the maiden name of the widow. Start looking for guardianship papers and possibly adoption papers. If you “lose” a child at the death of one or both parents, start searching census records (beginning with the U.S. federal census of 1850 and the UK census in 1851) for the child being enumerated in another residence, particularly in a relative’s home. In the absence of relatives, the county, parish, state, or province may have committed the child to an orphanage, orphan asylum, or a poorhouse. Leave no stone unturned. Check the respective court minutes and files for the year following a parent’s death for any evidence of legal actions regarding a child. You might be surprised at what you locate.

Witnesses are important. By law, they cannot inherit in a will; however, they may be relatives of the deceased. It is not uncommon to find an in-law as a witness. Bondsmen involved in the settlement of an estate were often relatives. If the wife of the testator was the executor of the estate, the bondsmen were usually her relatives. (If you do not know the maiden name of the wife, check the surnames of the bondsmen carefully because one of them may have been her brother.)

You will almost always find an inventory of the estate in the probate packet. The executor or administrator of the estate is first charged by the court to determine the assets, the debts, and the receivables of an estate in order to properly determine what needs to be done to divide or dispose of it. The inventory often paints a colorful picture of the way of life of the deceased. The type of furniture listed and the presence or absence of books, farm equipment, livestock, and real and personal property listed in the inventory all tell us what type of life and what social status the person enjoyed—or did not enjoy.

Obviously, there are many things to consider when reviewing wills and probate packet contents. Just a few of the many things to consider are the location, the laws in effect at the time, the religious affiliation of the testator, the size of the estate, and the presence or absence of a spouse, children, brothers, sisters, and parents.

When researching probate records, don’t overlook the probate court minutes. Entries are indexed by name of the testator, and they document every action relating to the estate that was filed with the court. these may provide additional clues.

Learn Why You Really Want to Examine Documents Yourself

There are many ways to obtain information about a will or probate packet. Since most of us cannot afford to travel to all the places where our ancestors lived, we may need to do some “mail order” business, writing or emailing for copies of courthouse records.

One of the problems with will and probate documentation published in books, magazines, periodicals, and on the Internet is that it may represent the interpretation of someone else who has looked at the documents. Unless that person is also a descendant of your ancestors, they may not have the family perspective and insight that you have. If they have transcribed the document verbatim, it might be correctly done but you can’t be sure unless you review it yourself. Even worse, materials that have been extracted or abstracted often contain omissions of details that might be of significant importance to your research. As an example, one will that I examined listed nine children’s names, some of which were double-barrel names, such as Billy Ray and Mary Lou. The insertion of extra commas in the transcription, extract, or abstract of these two children’s names could easily turn these two children’s names into four children—and wouldn’t that play havoc with your research efforts?

Watch wills carefully for names of children. Don’t make any assumptions. One of my friends researched her great-great-grandfather’s family and was convinced that there were seven children in the family. That was until she studied the actual will of the great-great-grandfather. In the will, the names Elizabeth and Mary had no comma between them. This led her to suspect that there was one daughter named Elizabeth Mary, rather than two daughters. Further investigation of marriage records in the county contradicted the one-daughter theory because she found that there were individual marriage records for two daughters, one married a year after her father’s death and the other two years later. Further, Elizabeth and Mary and their respective spouses settled on land that had been part of their father’s holdings and appeared there on subsequent census records.

Locate and Obtain Copies of Wills and Probate Documents

Wills, testaments, codicils, and other probate documents can be found in a variety of places. It is important to start in the area in which the person lived and make contact with the courts that had jurisdiction at that time, if they still exist.

In England, this may be difficult for older wills that at one time were handled by different levels of ecclesiastical courts that no longer exist. From the 13th century until 1858, church courts handled the entire probate process. Their jurisdictions sometimes overlapped and their administrative powers were not always clear. In addition, English wills that required the probate of an estate containing multiple pieces of land could be complicated if the parcels were in multiple church administrative districts. In those cases, a level of ecclesiastical court whose administrative level included all of the districts in which the lands were located handled the probate process. Those early ecclesiastical records were written in Latin and may present you with difficulty, both with the language used and the ancient handwriting style. It is important to understand the structure of the jurisdictions in the specific time period you are researching before undertaking a search for your English ancestor’s will. It was not until 1858 that civil courts began handling probate and a more standard approach was put in place.

Probate documents may be encountered in many forms. The original documents may still exist and may be filed with the records of the court that handled the process. Look for court minutes and other evidence of the proceedings. Many courts and administrative offices have microfilmed their court records. Microfilm provides for compact storage of these voluminous records while preserving the originals. Microfilm also allows for the economic duplication of the records for access and use in multiple locations, and makes printing and copying simple and inexpensive.

You may also find that some original probate documents have been digitized and made available on the Internet. The Scottish Archive Network (SCAN) has made more than half a million Scottish wills and testaments dating from 1500 to 1901 accessible in digital format at www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk. Individual counties, municipalities, and courts also have digitized records. A particularly impressive effort has been accomplished in Alachua County, Florida, with the ongoing digitization of the county’s Ancient Records Archives. This collection of indexed and, in some cases, transcribed documents can be seen at www.clerk-alachua-fl.org/Archive.

Obtain Information from the Social Security Administration and Railroad Retirement Board

The Social Security Administration (SSA) was established by an act of the U.S. Congress in 1935, in the depths of the Great Depression. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration was hard at work trying to help the United States recover economically through a number of social and financial programs. One area that required attention was that of old-age pensions. Older Americans were at significant risk of financial ruin during the Depression, and old-age pensions were primarily only available from some state and local governments. Many of those pension programs were faltering or had collapsed, and Congress was under pressure from the administration and from the public to take action.

The Social Security Act of 1935 established a national program for Americans over the age of 65 to receive benefits, and defined the structure and criteria for participation of those people in the work force and their employers to contribute to their retirement security. The program would not begin for several years and credit would not be given for any service prior to 1937.

In the meantime, railroad employees clamored for a program that would provide credit for prior service and an unemployment compensation program. Legislation passed in 1934, 1935, and 1937 established the Railroad Retirement program for employees of the U.S. railroads (more about that later in this section).

At the beginning of the program, in order to determine which persons would immediately be eligible to receive unemployment benefits, the SSA used the 1880 U.S. federal census as a reference to help verify the age of recipients. The SSA formed a special branch called the Age Search group to handle this function. That branch still exists today to perform the same function. The Age Search group quickly determined that searching the 1880 census Population Schedules for a single person’s enumeration listing was a highly laborious process. The SSA therefore commissioned the creation of an indexing system to assist in the search process. It was at that time that the Soundex coding system was developed for this program, and the first index was created for the 1880 census. Index cards were prepared by a group of employees of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and these cards were created only for households in which there were children aged ten and under. After the 1880 census was Soundexed, indexes were prepared for entire households in the 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930 censuses. This is the same Soundex and Miracode coding scheme described earlier in this book.

In order to pay retirement pension benefits to an applicant, the SSA required that applicant to prove his or her age eligibility. While the Soundex system was used by the Age Search group, the person applying for benefits had to a) have applied for and been assigned a Social Security number (SSN), b) prove his or her identity, and c) provide evidence of his or her age. (Persons with disabilities who could not work also later became eligible for Social Security benefits, and their requirements were the same.)

Social Security Numbers were assigned by offices in each state and territory, with each geographical division (state and territory) having been assigned a block of numbers. As is still the case today, the SSN consisted of three groups of digits: the first group of three digits represented the area in which the assignment was made; the next two digits represented a group; and the last group of four digits was a serial number, chronologically assigned. These numbers were assigned at the time that the applicant completed the SS-5 application form, such as the one shown in Figure 6-20, to obtain the SSN. The first group of three represents where the applicant’s SSN was assigned, and not necessarily where the person was born. This is an important distinction, and a source of confusion and misunderstanding among many genealogical researchers.

FIGURE 6-20 A photocopy of the SS-5 application form from the Social Security Administration

When a beneficiary dies, it is a legal requirement to notify the SSA so that it can immediately stop payments. A benefit check for the last partial month of the person’s life usually must be returned, and the SSA has a procedure for handling the final payment. The SSA now requires a copy of a death certificate or other form of written proof of death.

The SSA’s records were maintained on paper until the early 1960s. At that time, data from the SS-5 forms of all known living persons with SSNs (along with the last known address) and information from all new applicants’ SS-5 forms were entered into a computer database. In addition, the SSA began maintaining benefit information by computer and entering death information as notifications of the deaths of recipients were received. Beginning in 1962, the Social Security Death Master File began to be produced electronically on a regular basis. Initially, it contained only about 17 percent of the reported deaths, but that increased to more than 92 percent in 1980. The percentage of completeness has varied up and down since then, and will never be 100 percent complete. The file has since come to be known as the Social Security Death Index, or SSDI, and is accessible for free at http://ssdi.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Genealogists with family members in the United States have used this valuable tool to locate the place of last residence or benefit payment in order to locate other records.

It is important to understand that the SSDI contains only information about deceased individuals, in compliance with both the Privacy Act, which protects individuals’ information for 72 years, and the Freedom of Information Act, which makes information available to the public. There are four criteria for a person’s information to be included in the SSDI:

- The person must be deceased.

- The person must have had a Social Security number assigned to him or her.

- The person must have applied for and received a Social Security benefit payment.

- The person’s death must have been reported to the Social Security Administration.

If a person was assigned a SSN and is deceased, but never received a benefit of any sort, he or she will not be found in the SSDI. For these persons, and for those persons who died prior to the computerization of the SSA records, you can still obtain a copy of their SS-5 application form from the SSA. All you need to do is write the SSA Freedom of Information Officer, provide the full name, address, and birth date of the individual, and request the SS-5. If you can provide the person’s SSN, the cost of obtaining an SS-5 at this writing is $27; without the SSN, the cost is $29. In addition, you can request a copy of a printout from the SSDI database known as a Numident. Numident is an acronym for Numerical Identification System. The Numident is nothing more than the data entered into the SSA database. The price of this document is $16 if you can provide the SSN or $18 if you cannot. Requests for SS-5 forms and Numident printouts can be made at https://secure.ssa.gov/apps9/eFOIA-FEWeb/internet/main.jsp or sent by mail to:

Social Security Administration

OEO FOIA Workgroup

300 N. Greene Street

P.O. Box 33022

Baltimore, Maryland 21290-3022

Your request to the SSA for a copy of the application (SS-5) for a person who never received a benefit and for whom the SSA wasn’t notified of the death may be denied. However, if you can supply evidence of the person’s death, such as a copy of a death certificate, you can appeal the decision and then receive the copy of their SS-5 form.

The U.S. Railroad Retirement Board (RRB) is the administrative body for the railroad workers’ retirement pension benefits system. The Railroad Retirement program is similar to Social Security but is administered by the RRB in Chicago, Illinois. Up until 1963, persons who worked for a railroad in the United States at the time they applied for a SSN were assigned a number between 700 and 728. Therefore, if you locate any document that lists a SSN whose first three digits are in that numbering range, you will know that the person worked for the railroad industry at the time he or she was assigned the number. You also will know to check first with the RRB for records.

A person who worked exclusively in the railroad industry will apply for and receive old-age pension benefits from Railroad Retirement. An individual who worked for both the railroad industry and elsewhere would have contributed to both a Railroad Retirement pension account and to Social Security during his or her working career. At the time of retirement, the person had to apply for a retirement pension benefit from either one or the other, but not both plans.

The RRB records you obtain may be more detailed, including earnings reports, copies of designation of beneficiary forms, and perhaps more. The address to which you would send your request, along with a check for $27 made payable to the Railroad Retirement Board, is

Congressional Inquiry Section

U.S. Railroad Retirement Board

844 North Rush Street

Chicago, Illinois 60611-2092

Use Historical Newspapers to Learn About Your Ancestor’s Life Events

Newspapers chronicle a community’s life and record the cultural, social, political, commercial, and agricultural conditions. Vast collections of newspapers have been microfilmed over time. Many of these, as well as surviving newsprint documents, are in the process of being digitized and every-word indexed, and are being made available online.

Historical newspapers that are being made available online are accessible in several ways. First, there are individual newspapers made available by their publishers. These are typically the more recent newspapers, from around 1985 to present. Accessing them may or may not require a fee.

Two centralized websites that can be used to locate and access them are OnlineNewspapers.com at www.onlinenewspapers.com and the Internet Public Library’s newspaper section at www.ipl.org/div/news. The Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., is compiling a collection of historical American newspapers from 1836 through 1922. This collection is freely accessible at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov. Don’t overlook digital newspaper collections that may have been compiled by libraries and archives worldwide. In the United States, many state libraries and archives have endeavored to identify all of the newspapers in their state that were ever published, acquire copies of the newspapers or microfilm, and digitize and index those materials. The British Library at www.bl.uk announced in mid-2010 that it has begun digitizing more than 40 million pages of its Newspaper Library collection in Colindale.

Next, there are databases of historical newspapers to which you can subscribe as an individual. One such example is NewspaperARCHIVE.com at http://newspaperarchive.com (see Figure 6-21). It claims to have the largest collection online with newspapers dating from 1753 to present. The Ancestry.com subscription service at www.ancestry.com and some of its geographical sites also include newspapers. Fold3.com at www.fold3.com, WorldVitalRecords.com at www.worldvitalrecords.com, and others include digitized newspaper collections. Another important subscription site is the Times Archive at http://archive.timesonline.co.uk/tol/archive, which provides access to the digitized archive of The Times of London from 1785 through 1985.

FIGURE 6-21 The death announcement for the author’s paternal grandmother’s first husband appeared in the Statesville Landmark on Tuesday, 12 July 1898. The digitized newspaper was discovered at NewspaperARCHIVE.com.

There are digitized historical newspaper database collections that are only available as institutional subscriptions to libraries and archives. ProQuest is a major provider of historical newspaper databases and their collections include the New York Times, Atlanta Constitution, Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, Toronto Star, Wall Street Journal, and many more. NewsBank, Inc., offers genealogy-specific databases such as “America’s GenealogyBank” and “America’s Obituaries & Death Notices.” America’s GenealogyBank (www.genealogybank.com) includes digitized and indexed U.S. newspapers from 1690 to 1977, historical books from 1801 to 1900, and historical documents from 1789 to 1980. America’s Obituaries & Death Notices includes obituaries from more recent newspapers from the 1970s and later.

You will want to check with your local public library, academic libraries, and with archives to determine what is available. If you hold a library card and your library subscribes to a historical newspaper collection, you may have remote access from home to connect and work with some of these databases.

Consider Other Institutional Record Types

You can see now how the investigative work you are doing and the scholarly methodologies you are using can begin to pay big dividends. In many of the examples I’ve shown in this chapter, I have tried to convey the ways that one record may provide clues and pointers to others.

As you encounter new sources of information, use your critical thinking skills to read between the lines. Consider the other institutional records that might add to your knowledge. These could include records from employers, unions, schools, professional organizations, civic and social clubs, and veterans groups, just to name a few. Just as with cemetery offices, you never know what information might be in these organizations’ files.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)