Chungcheong

Highlights

Boryeong mud festival Get dirty on the beach at the most enjoyable festival on the Korean calendar.

West Sea islands Take a ferry to these tiny, beach-pocked isles, home to fishing communities and a relaxed way of life hard to find on the mainland.

Buyeo and Gongju Head to the former capitals of the Baekje dynasty to feast your eyes on their regal riches.

Independence Hall of Korea Delve into the nationalistic side of the Korean psyche at this huge testament to the country’s survival of Japanese occupation.

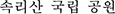

Beopjusa temple Gaze in awe at the world’s tallest bronze Buddha, before taking a hike in the surrounding national park.

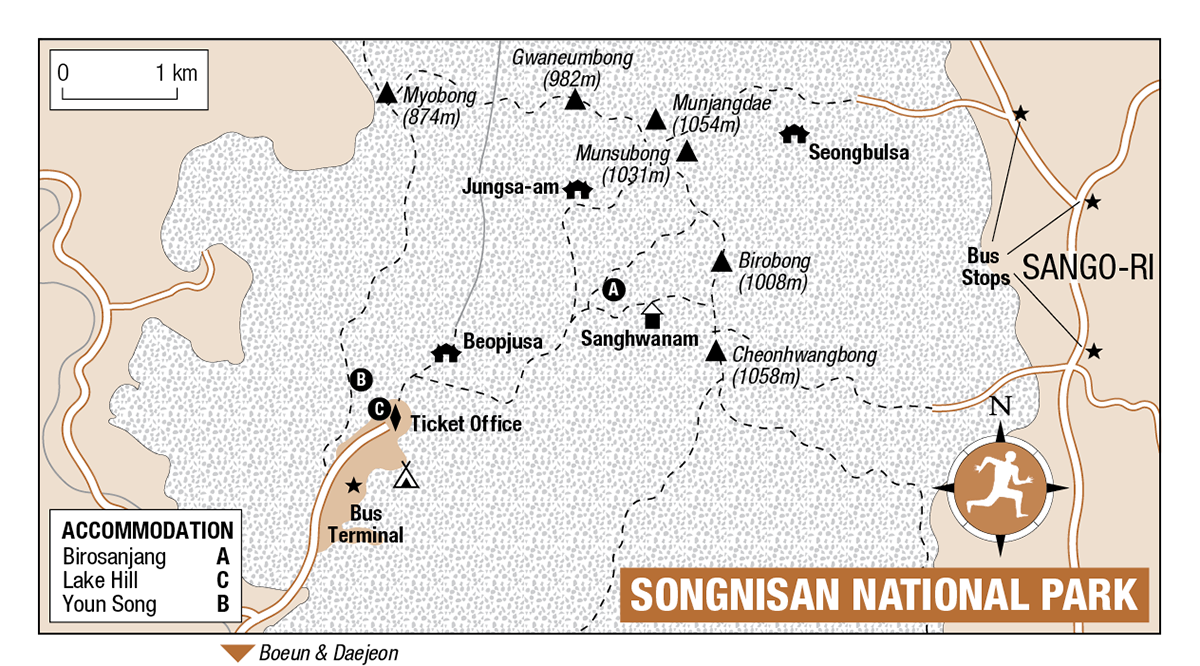

Danyang Take a midnight stroll, makkeolli in hand, along this tiny town’s lakeside promenade.

Guinsa Clamber around the snakelike alleyways of what may well be Korea’s most distinctive temple.

Chungcheong

Of South Korea’s principal regions, Chungcheong ( ) is the least visited by foreign travellers, most of whom choose to rush through it on buses and trains to Gyeongju or Busan in the southeast, or over it on planes to Jeju-do. But to do so is to bypass the heart of the country, a thrillingly rural mishmash of rice paddies, ginseng fields, national parks and unhurried islands. One less obvious Chungcheong attraction is the local populace – the Chungcheongese are noted throughout Korea for their relaxed nature. Here you’ll get less pressure at the markets, or perhaps even notice a delay of a second or two when the traffic lights change before being deafened by a cacophony of car horns. The region’s main cities are noticeably laid-back by Korean standards, and Chungcheongese themselves, particularly those living in the countryside, speak at a markedly slower pace than other Koreans.

) is the least visited by foreign travellers, most of whom choose to rush through it on buses and trains to Gyeongju or Busan in the southeast, or over it on planes to Jeju-do. But to do so is to bypass the heart of the country, a thrillingly rural mishmash of rice paddies, ginseng fields, national parks and unhurried islands. One less obvious Chungcheong attraction is the local populace – the Chungcheongese are noted throughout Korea for their relaxed nature. Here you’ll get less pressure at the markets, or perhaps even notice a delay of a second or two when the traffic lights change before being deafened by a cacophony of car horns. The region’s main cities are noticeably laid-back by Korean standards, and Chungcheongese themselves, particularly those living in the countryside, speak at a markedly slower pace than other Koreans.

Today split into two provinces, Chungcheong was named in the fourteenth century by fusing the names of Chungju and Cheongju, then its two major cities – they’re still around today, but of little interest to travellers (Cheongju did, however, produce the world’s first book). To the west lies Chungnam ( ), a province whose name somewhat confusingly translates as “South Chungcheong”. Its western edge is washed by the West Sea, and has a few good beaches – the strip of white sand in Daecheon is one of the busiest in the country, with the summer revelry hitting its zenith each July at an immensely popular mud festival. Off this coast are a number of accessible islands – tiny squads of rock stretch far beyond the horizon into the West Sea, and sustain fishing communities that provide a glimpse into pre-karaoke Korean life. Heading inland instead, the pleasures take a turn for the traditional: the small cities of Buyeo and Gongju fuctioned as capitals of the Baekje dynasty (18 BC–660 AD) just as the Roman Empire was collapsing, yet each still boasts a superb wealth of dynastic sights. Both are home to fortresses, regal tombs and museums filled with gleaming jewellery of the period, which went on to have a profound influence on Japanese craft. As you head further east, the land becomes ever more mountainous. Anyone hiking across the spine of Songnisan national park will find a couple of gorgeous temples on the way, and on dropping down will be able to grab a bus to Daejeon, Chungcheong’s largest city. North of Daejeon, and actually part of Seoul’s sprawling subway network, is Cheonan, which is home to the country’s largest, and possibly most revealing, museum.

), a province whose name somewhat confusingly translates as “South Chungcheong”. Its western edge is washed by the West Sea, and has a few good beaches – the strip of white sand in Daecheon is one of the busiest in the country, with the summer revelry hitting its zenith each July at an immensely popular mud festival. Off this coast are a number of accessible islands – tiny squads of rock stretch far beyond the horizon into the West Sea, and sustain fishing communities that provide a glimpse into pre-karaoke Korean life. Heading inland instead, the pleasures take a turn for the traditional: the small cities of Buyeo and Gongju fuctioned as capitals of the Baekje dynasty (18 BC–660 AD) just as the Roman Empire was collapsing, yet each still boasts a superb wealth of dynastic sights. Both are home to fortresses, regal tombs and museums filled with gleaming jewellery of the period, which went on to have a profound influence on Japanese craft. As you head further east, the land becomes ever more mountainous. Anyone hiking across the spine of Songnisan national park will find a couple of gorgeous temples on the way, and on dropping down will be able to grab a bus to Daejeon, Chungcheong’s largest city. North of Daejeon, and actually part of Seoul’s sprawling subway network, is Cheonan, which is home to the country’s largest, and possibly most revealing, museum.

Heading east instead will bring you to the province of Chungbuk ( ; “North Chungcheong”). As Korea’s only landlocked province, this could be said to represent the heart of the country, a predominantly rural patchwork of fields and peaks, with three national parks within its borders. Songnisan is deservedly the most popular, and has a number of good day-hikes emanating from Beopjusa, a highly picturesque temple near the park’s main entrance. Sobaeksan is less visited but just as appealing to hikers; it surrounds the lakeside resort town of Danyang, which makes a comfortable base for exploring the caves, fortresses and sprawling temple of Guinsa on the province’s eastern flank.

; “North Chungcheong”). As Korea’s only landlocked province, this could be said to represent the heart of the country, a predominantly rural patchwork of fields and peaks, with three national parks within its borders. Songnisan is deservedly the most popular, and has a number of good day-hikes emanating from Beopjusa, a highly picturesque temple near the park’s main entrance. Sobaeksan is less visited but just as appealing to hikers; it surrounds the lakeside resort town of Danyang, which makes a comfortable base for exploring the caves, fortresses and sprawling temple of Guinsa on the province’s eastern flank.

For centuries, perhaps even millennia, the ginseng root has been used in Asia for its medicinal qualities, particularly its ability to retain or restore the body’s Yin–Yang balance; for a time, it was valued more highly by weight than gold. Even today, Korean ginseng is much sought after on the global market, due to the country’s ideal climatic conditions; known locally as insam ( ), much of it is grown in the Chungcheong provinces under slanted nets of black plastic. The roots take anything up to six years to mature, and suck up so much nutrition from the soil that, once harvested, no more ginseng can be planted in the same field for over a decade.

), much of it is grown in the Chungcheong provinces under slanted nets of black plastic. The roots take anything up to six years to mature, and suck up so much nutrition from the soil that, once harvested, no more ginseng can be planted in the same field for over a decade.

The health benefits of ginseng have been much debated in recent years, and most of the evidence in favour of the root is anecdotal rather than scientific. There are, nonetheless, hordes of admirers, and ginseng’s stock rose further when it rode the crest of the “healthy living” wave that swept across Korea just after the turn of the millennium. Today it’s possible to get your fix in pills, capsules, jellies, chewing gum or boiled sweets, as well as the more traditional tea or by eating the root raw. As the purported benefits depend on the dosage and type of ginseng used (red or white), it’s best to consult a practitioner of oriental medicines, but one safe – and delicious – dish is samgyetang ( ), a tasty and extremely healthy soup made with a ginseng-stuffed chicken, available for around W8000 across the land. Or for a slightly quirky drink, try mixing a sachet of ginseng granules and a spoon of brown sugar into hot milk – your very own ginseng latte.

), a tasty and extremely healthy soup made with a ginseng-stuffed chicken, available for around W8000 across the land. Or for a slightly quirky drink, try mixing a sachet of ginseng granules and a spoon of brown sugar into hot milk – your very own ginseng latte.

Coastal Chungnam

Within easy reach of Seoul, Chungnam’s coast is a popular place for anyone seeking to escape the capital for a bit of summer fun. Inevitably, the main attractions are the beaches, with the white stretches of Mallipo and Daecheon the most visited; the latter’s annual mud festival is one of the wildest and busiest events on the peninsula. It’s a short ferry trip from the mainland bustle to the more traditional offshore islands, a sleepy crew strung out beyond the horizon and almost entirely dependent on fishing.

Long, wide and handsome, DAECHEON BEACH ( ) is by far the most popular on Korea’s western coast, hauling in a predominantly young crowd. In the summer this 3km-long stretch of white sand becomes a sea of people, having fun in the water by day, then drinking and letting off fireworks until the early hours. The revelry reaches its crescendo each July with the Boryeong mud festival, a week-long event that seems to rope in (and sully) almost every expat in the country. Mud, mud and more mud – wrestle or slide around in it, throw it at your friends or smear it all over yourself, then take lots and lots of pictures – this is one of the most enjoyable festivals on the calendar (see

) is by far the most popular on Korea’s western coast, hauling in a predominantly young crowd. In the summer this 3km-long stretch of white sand becomes a sea of people, having fun in the water by day, then drinking and letting off fireworks until the early hours. The revelry reaches its crescendo each July with the Boryeong mud festival, a week-long event that seems to rope in (and sully) almost every expat in the country. Mud, mud and more mud – wrestle or slide around in it, throw it at your friends or smear it all over yourself, then take lots and lots of pictures – this is one of the most enjoyable festivals on the calendar (see  www.mudfestival.or.kr for more details). At other times you can still sample the brown stuff at the Mud House (

www.mudfestival.or.kr for more details). At other times you can still sample the brown stuff at the Mud House ( ; 8am–6pm; W4000 after W1000 foreigner discount), the most distinctive building on the beachfront, where mud massages cost from W25,000. The ticket gets you entry to an on-site sauna, at which you can bathe in a mud pool or even paint yourself with the stuff; all manner of mud-based cosmetics are on sale at reception, including mud shampoo, soap and body cream. In summer, rent banana boats, jet-skis and large rubber tubes, or even a quad bike to ride up and down the prom.

; 8am–6pm; W4000 after W1000 foreigner discount), the most distinctive building on the beachfront, where mud massages cost from W25,000. The ticket gets you entry to an on-site sauna, at which you can bathe in a mud pool or even paint yourself with the stuff; all manner of mud-based cosmetics are on sale at reception, including mud shampoo, soap and body cream. In summer, rent banana boats, jet-skis and large rubber tubes, or even a quad bike to ride up and down the prom.

Nine kilometres south of the beach is Muchangpo ( ), a settlement that becomes popular for a few days every month when the tides retreat to reveal a path linking the beach with a small nearby island, an event inevitably termed “Moses’ Miracle”; the sight of a line of people seemingly walking across water is quite something. For advice on the tides phone the tourist information line on

), a settlement that becomes popular for a few days every month when the tides retreat to reveal a path linking the beach with a small nearby island, an event inevitably termed “Moses’ Miracle”; the sight of a line of people seemingly walking across water is quite something. For advice on the tides phone the tourist information line on  041/1330.

041/1330.

Arrival and information

Getting to Daecheon beach can be a little tricky. It’s just 15km from the town of Boryeong ( ), and the two places have been known to trade names on occasion – hence the “Boryeong” Mud Festival. Coming from elsewhere in Korea, you’ll arrive in Boryeong, whose train station (known as Daecheon) and bus station (this time Boryeong) are right next to each other. From both stations there are buses to the beach every half-hour or so (15min; W1800); get off as soon as you make a right at the Legrand Beach Hotel. Alternatively, the beach is less than W10,000 by taxi from either station. The bus route finishes at Daecheon harbour, at the northern end of the beach; you’ll have to go here to take a ferry to one of the nearby islands.

), and the two places have been known to trade names on occasion – hence the “Boryeong” Mud Festival. Coming from elsewhere in Korea, you’ll arrive in Boryeong, whose train station (known as Daecheon) and bus station (this time Boryeong) are right next to each other. From both stations there are buses to the beach every half-hour or so (15min; W1800); get off as soon as you make a right at the Legrand Beach Hotel. Alternatively, the beach is less than W10,000 by taxi from either station. The bus route finishes at Daecheon harbour, at the northern end of the beach; you’ll have to go here to take a ferry to one of the nearby islands.

There’s an information booth near the mud centre where staff can reserve accommodation both in Daecheon and – helpfully – on the offshore islands, but you’d be lucky to find an English-speaker here; a map and some controlled mime should be enough to land you a booking.

Accommodation

Although there’s very little at the top end of the scale, motels and minbak are everywhere, and even at the peak of summer you can usually find a bed without too much difficulty; prices can go through the roof on summer weekends and holidays, though with time, patience and a few words with the ubiquitous ajummas, you should find a bare-bones room for W30,000. Travellers and locals alike often save money by cramming as many people as possible into a room, or staying out all night on the beach with a few drinks. Lastly, there’s a small campground with shower facilities behind the mud centre, which costs W5000 per tent in July and August, but is free to use at other times. The options listed here are all between the bus stop and the mud centre.

Legrand Beach Hotel  041/931-1020. The only higher-end option in the area, although rooms are vastly overpriced for what they are. Equally poor value is the near-decrepit on-site water park, tickets to which cost around W25,000.

041/931-1020. The only higher-end option in the area, although rooms are vastly overpriced for what they are. Equally poor value is the near-decrepit on-site water park, tickets to which cost around W25,000.

Moktobang Motel  041/931-7172. Easy to spot on account of its distinctive oriental roof, with wood-panelled and quite pleasing rooms all with en-suite facilities.

041/931-7172. Easy to spot on account of its distinctive oriental roof, with wood-panelled and quite pleasing rooms all with en-suite facilities.

Motel Coconuts

Motel Coconuts  041/934-6595. Homely, family-run motel with cheerily decorated en-suite rooms, decent showers and cable TV. Be careful not to trip on the kids’ toys in the lobby.

041/934-6595. Homely, family-run motel with cheerily decorated en-suite rooms, decent showers and cable TV. Be careful not to trip on the kids’ toys in the lobby.

Eating

Daecheon’s culinary scene is simple – fish, fish and more fish. The seafront is lined with seafood restaurants and the competition is fierce – locals here are fond of literally dragging customers in. Best on the promenade is Hwanghae ( ), whose blue-ball outdoor lights are easy to spot at night. Most places display their still-alive goods in outdoor tanks; among the myriad options are eel, blue crabs, razor clams and sea cucumbers. Another speciality is Jogae-gui (

), whose blue-ball outdoor lights are easy to spot at night. Most places display their still-alive goods in outdoor tanks; among the myriad options are eel, blue crabs, razor clams and sea cucumbers. Another speciality is Jogae-gui ( ), a shellfish barbecue that costs from around W15,000 per person; there’s usually a two-person minimum for this or any other meal, meaning that solo travellers may have to subsist on Hoe-deopbap (

), a shellfish barbecue that costs from around W15,000 per person; there’s usually a two-person minimum for this or any other meal, meaning that solo travellers may have to subsist on Hoe-deopbap ( ), chunks of raw fish with spicy sauce served on a bed of rice and leaves (usually W10,000). A more rustic patch of restaurants can be found near Daecheon harbour; these are quite atmospheric, especially in the evenings when the ramshackle buildings, bare hanging bulbs and coursing sea water may make you feel as though you’ve been shunted back in time a couple of decades. For anything other than fish you may have to rely on snack stalls or instant noodles from one of the convenience stores; the latter are also the source of most of the alcohol consumed in Daecheon, though there are plenty of old-fashioned bars lining the seafront.

), chunks of raw fish with spicy sauce served on a bed of rice and leaves (usually W10,000). A more rustic patch of restaurants can be found near Daecheon harbour; these are quite atmospheric, especially in the evenings when the ramshackle buildings, bare hanging bulbs and coursing sea water may make you feel as though you’ve been shunted back in time a couple of decades. For anything other than fish you may have to rely on snack stalls or instant noodles from one of the convenience stores; the latter are also the source of most of the alcohol consumed in Daecheon, though there are plenty of old-fashioned bars lining the seafront.

From Daecheon harbour, a string of tiny islands stretches beyond the horizon into what Koreans term the West Sea, a body of water known internationally as the Yellow Sea. From their distant shores, the mainland is either a lazy murmur on the horizon or altogether out of sight, making this a perfect place to kick back and take it easy. Beaches and seafood restaurants are the main draw, but it’s also a joy to sample the unhurried island lifestyle that remains unaffected by the changes that swept through the mainland on its course to First World status; these islands therefore, provide the truest remnants of pre-industrial Korean life. Fishing boats judder into the docks where the sailors gut and prepare their haul with startling efficiency; it’s sometimes possible to buy fish directly from them. Restaurants on the islands are usually rickety, family-run affairs serving simple Korean staples.

Island practicalities

Ferries connect the islands in two main circuits, though with so few sailings, you won’t be able to see more than one or two islands in a day. For circuit one, there are two sailings daily from Daecheon (8.10am & 3pm; 40min to Hodo, 20min more to Nokdo and a further 30min to Oeyeondo, from where return ferries leave at 10am & 4.40pm). Circuit two is accessible from either Daecheon or Anmyeondo. At least three sailings per day head around this loop; those leaving Daecheon at 7.30am and 12.50pm head clockwise, arriving first at Sapsido, while the 4pm ferry heads in the opposite direction, stopping first at Anmyeondo.

Remember to bring enough money for your stay, as most of the isles lack banks – the majority have mini-markets, but these can be hard to find as they tend to double as family homes. All islands have minbak accommodation, though don’t expect anything too fancy – the rooms will be small and bare, and you’ll probably have to sleep on a blanket on the floor. Prices start at W20,000 per night, and increase in summer.

Circuit one

This circuit fires 53km out to sea, terminating at the weatherbeaten island group Oeyeondo, before heading back to the mainland on the same route; as the ferries are for foot passengers only, the islands they visit are quieter than those on loop two.

The first stop is Hodo ( ), which attracts visitors for its beaches without the fuss of those on the mainland; the island’s best beach is a curl of white sand just a short walk from the ferry dock and is great for swimming. Around the terminal are plenty of minbak rooms – pretty much every dwelling in the village will accept visitors, though there are only around sixty on the whole island. Try to track down Mr Choi at Gwangcheon Minbak (

), which attracts visitors for its beaches without the fuss of those on the mainland; the island’s best beach is a curl of white sand just a short walk from the ferry dock and is great for swimming. Around the terminal are plenty of minbak rooms – pretty much every dwelling in the village will accept visitors, though there are only around sixty on the whole island. Try to track down Mr Choi at Gwangcheon Minbak ( ); he’s the proud owner of the only land vehicle on Hodo (a beat-up 4WD) and can be persuaded to give free nighttime rides through the forest or a splash across the mudflats if the tide is out – tremendous fun. Next stop is Nokdo (

); he’s the proud owner of the only land vehicle on Hodo (a beat-up 4WD) and can be persuaded to give free nighttime rides through the forest or a splash across the mudflats if the tide is out – tremendous fun. Next stop is Nokdo ( ), the smallest island of the three and home to some superb hill trails. Unlike on the other islands, the hillside town and its accommodation options are a fair walk from the ferry dock – everyone will be going the same way, so you should be able to hitch a lift without too much bother. The ferries make their final stop at Oeyeondo (

), the smallest island of the three and home to some superb hill trails. Unlike on the other islands, the hillside town and its accommodation options are a fair walk from the ferry dock – everyone will be going the same way, so you should be able to hitch a lift without too much bother. The ferries make their final stop at Oeyeondo ( ), a well-weathered family of thickly forested specks of land. This has the busiest port on the loop, with walking trails heading up to the island’s twin peaks, as well as a tiny beach that’s good for sunsets.

), a well-weathered family of thickly forested specks of land. This has the busiest port on the loop, with walking trails heading up to the island’s twin peaks, as well as a tiny beach that’s good for sunsets.

Circuit two

This is a proper loop, with ferries heading both ways around a circle that starts and ends in Daecheon. These boats can accommodate vehicles, meaning that the islands here are busier than on circuit one; however, the salty and remote appeal remains. All have minbak accommodation from around W20,000 (more in summer).

As you head clockwise, the first port of call is Sapsido ( ), the most popular island in the whole area (and pronounced “sap-shi-do”). Its shores are dotted with craggy rock formations, some with a hair-like covering of juniper or pine, while the island’s interior is crisscrossed with networks of dirt tracks – it’s possible to walk from one end to the other in under an hour. Depending on the tides, ferries will call at one of two ports – there are minbak aplenty around each, and both have decent beaches within walking distance, but make sure that you know which one to go to when you’re leaving the island. Next stop is Janggodo (

), the most popular island in the whole area (and pronounced “sap-shi-do”). Its shores are dotted with craggy rock formations, some with a hair-like covering of juniper or pine, while the island’s interior is crisscrossed with networks of dirt tracks – it’s possible to walk from one end to the other in under an hour. Depending on the tides, ferries will call at one of two ports – there are minbak aplenty around each, and both have decent beaches within walking distance, but make sure that you know which one to go to when you’re leaving the island. Next stop is Janggodo ( ), whose name derives from its contours, which are said to be similar to the Korea janggo drum (though it’s actually shaped more like a banana). Home to some stupendous rock formations, it’s popular with families and, thanks to some particularly good beaches, the trendier elements of the Korean beach set. Local buses wait at the northern terminal (there are two) to take passengers to the minbak area (it’s a little far to walk). It’s then a short hop across a strait usually filled with fishing nets to little Godaedo (

), whose name derives from its contours, which are said to be similar to the Korea janggo drum (though it’s actually shaped more like a banana). Home to some stupendous rock formations, it’s popular with families and, thanks to some particularly good beaches, the trendier elements of the Korean beach set. Local buses wait at the northern terminal (there are two) to take passengers to the minbak area (it’s a little far to walk). It’s then a short hop across a strait usually filled with fishing nets to little Godaedo ( ), an island renowned for its seafood; thus the pungent aroma that can often be smelt from the ferry. Depending on the ferry and the tides, you may also stop at Wonsando (

), an island renowned for its seafood; thus the pungent aroma that can often be smelt from the ferry. Depending on the ferry and the tides, you may also stop at Wonsando ( ) and Hyojado (

) and Hyojado ( ) on your way back to Daecheon, but one certain stop is Anmyeondo (

) on your way back to Daecheon, but one certain stop is Anmyeondo ( ); the largest island in the group, and the only one connected to the mainland by road. It also constitutes the most accessible part of Taean Haean National Park (

); the largest island in the group, and the only one connected to the mainland by road. It also constitutes the most accessible part of Taean Haean National Park ( ). White sand beaches fill the coves that dot Anmyeondo’s west coast, many of them only accessible by footpath from a small road that skirts the shore between Anmyeon (

). White sand beaches fill the coves that dot Anmyeondo’s west coast, many of them only accessible by footpath from a small road that skirts the shore between Anmyeon ( ), the main settlement and transport hub, and Yeongmok (

), the main settlement and transport hub, and Yeongmok ( ), a port village at the southern cape that receives ferries from Daecheon and other West Sea islands. Connecting the two are buses that meet the ferries and run approximately once an hour.

), a port village at the southern cape that receives ferries from Daecheon and other West Sea islands. Connecting the two are buses that meet the ferries and run approximately once an hour.

The Baekje capitals

Gongju and Bueyo are two small settlements in Chungnam that were, for a time, capitals of the Baekje dynasty which controlled much of the Korean peninsula’s southwestern area during the Three Kingdoms period. Once known as Ungjin, Gongju became the second capital of the realm in 475, when it was moved from Wiryeseong (now known as Seoul), but held the seat of power for only 63 years before it was passed to Buyeo, a day’s march to the southwest. Buyeo (then named Sabi) lasted a little longer until the dynasty was choked off in 660 by the powerful Silla empire to the east, which went on to unify the peninsula. Today, these three cities form an uneven historical triangle, weighed down on one side by Gyeongju’s incomparable wealth of riches. Although the old Silla capital sees by far the most foreign tourists, the Baekje pair’s less heralded sights can easily fill a weekend. Many of these echo those of the Silla capital – green grassy mounds where royalty were buried, imposing fortresses, lofty pavilions and ornate regal jewellery. Unabashedly excessive, yet at the same time achieving an ornate simplicity, Baekje jewellery attained an international reputation and went on to exert an influence on the Japanese craft of jewellery-making; some well-preserved examples in both cities can be found at their museums, which are two of Korea’s best. Additionally, the Baekje Culture Festival takes place each September, with colourful parades and traditional performances in both Buyeo and Gongju; see  www.baekje.org for more.

www.baekje.org for more.

The two cities remain off the radar of most international travellers, and most who visit do so on day-trips from Seoul. Much of this can be attributed to the fact that there’s next to no higher-end accommodation in either city, though a resort has recently opened up just outside Buyeo. Though unheralded even by Koreans, the cities’ unassuming restaurants are a different story altogether – though extremely earthy, the food on offer here is some of the best and most traditional in the land, and an extremely well-preserved secret.

The Baekje dynasty was one of Korea’s famed Three Kingdoms – Goguryeo and Silla being the other two – and controlled much of southwestern Korea for almost seven hundred years. The Samguk Sagi, Korea’s only real historical account of the peninsula in these times, claims that Baekje was a product of sibling rivalry – it was founded in 18 BC by Onjo, whose father had kick-started the Goguryeo dynasty less than twenty years beforehand, in present-day North Korea; seeing the reins of power passed on to his elder brother Yuri, Onjo promptly moved south and set up his own kingdom.

Strangely, given its position facing China on the western side of the Korean peninsula, Baekje was more closely allied with the kingdom of Wa in Japan – at least one Baekje king was born across the East Sea – and it became a conduit for art, religion and customs from the Asian mainland. This fact is perhaps best embodied by the Baekje artefacts displayed in the museums in Buyeo and Gongju, which contain lacquer boxes, pottery and folding screens not dissimilar to the craftwork that Japan is now famed for.

Though the exact location of the first Baekje capitals is unclear, it’s certain that Gongju and Buyeo were its last two seats of power. Gongju, then known as Ungjin, was capital from 475 to 538; during this period the aforementioned Three Kingdoms were jostling for power, and while Baekje leaders formed an uneasy alliance with their Silla counterparts the large fortress of Gongsanseong was built to protect the city from Goguryeo attacks. The capital was transferred to Sabi – present-day “Buyeo” – which also received a fortress-shaped upgrade. However, it was here that the Baekje kingdom finally ground to a halt in 660, succumbing to the Silla forces that, following their crushing of Goguryeo shortly afterwards, went on to rule the whole peninsula.

Though local rebellions briefly brought Baekje back to power in the years leading up to the disintegration of Unified Silla, it was finally stamped out by the nascent Goryeo dynasty in 935. Despite the many centuries that have elapsed since, much evidence of Baekje times can still be seen today in the form of the regal burial mounds found in Gongju and Buyeo.

The smaller and sleepier of the Baekje duo, BUYEO ( ) is nonetheless worth a visit. The Baekje seat of power was transferred here from Gongju in 538, and saw six kings come and go before the abrupt termination of the dynasty in 660, when General Gyebaek led his five thousand men into one last battle against a Silla-Chinese coalition ten times that size. Knowing that his resistance would prove futile, the general killed his wife and children before heading into combat, preferring to see them dead than condemn them to slavery. Legend has it that thousands of the town’s women threw themselves off a riverside cliff when the battle had been lost, drowning both themselves and the Baekje dynasty. Today, this cliff and the large, verdant fortress surrounding it are the town’s biggest draw, along with an excellent museum.

) is nonetheless worth a visit. The Baekje seat of power was transferred here from Gongju in 538, and saw six kings come and go before the abrupt termination of the dynasty in 660, when General Gyebaek led his five thousand men into one last battle against a Silla-Chinese coalition ten times that size. Knowing that his resistance would prove futile, the general killed his wife and children before heading into combat, preferring to see them dead than condemn them to slavery. Legend has it that thousands of the town’s women threw themselves off a riverside cliff when the battle had been lost, drowning both themselves and the Baekje dynasty. Today, this cliff and the large, verdant fortress surrounding it are the town’s biggest draw, along with an excellent museum.

Arrival and information

Buses arrive at a tiny station in the centre of town; from here most major sights – as well as the majority of motels and restaurants – are within walking distance, though it’s easy to hunt down a cab if necessary. Buyeo’s main street runs between two roundabouts – Boganso Rotary to the north, and Guncheon Rotary 1km to the south. By the latter is a statue of General Gyebaek, while next to the fortress entrance (east of the northern roundabout) is a tourist information office (daily 9am–6pm;  041/830-2523), where’s you’ll usually find an English-speaker.

041/830-2523), where’s you’ll usually find an English-speaker.

Accommodation

As long as you’re not too fussy, accommodation is easy to find in Buyeo, and a high-end resort finally opened up just outside the city in 2010. Try to avoid the area around the bus terminal, which contains some rather insalubrious places to stay.

Baekje Hotel  041/236-7979. Inconveniently located a short taxi-ride from the bus terminal, this is the only official tourist accommodation in central Buyeo. Rooms are a little drab but fairly priced, and there’s a small café-bar on site.

041/236-7979. Inconveniently located a short taxi-ride from the bus terminal, this is the only official tourist accommodation in central Buyeo. Rooms are a little drab but fairly priced, and there’s a small café-bar on site.

Lotte Resort

Lotte Resort  041/939-1000,

041/939-1000,  www.lottebuyeoresort.com. Superbly designed resort hotel, whose pleasing, twin-horseshoe-shaped exterior is best described as “neo-Baekje”. Although service is patchy, it has some of the best-value rooms in the land, with five-star facilities for just W120,000. It’s located a W7000 taxi ride from central Buyeo, next to Baekje Cultural Land.

www.lottebuyeoresort.com. Superbly designed resort hotel, whose pleasing, twin-horseshoe-shaped exterior is best described as “neo-Baekje”. Although service is patchy, it has some of the best-value rooms in the land, with five-star facilities for just W120,000. It’s located a W7000 taxi ride from central Buyeo, next to Baekje Cultural Land.

Motel VIP  041/832-3700. Near Boganso Rotary, with the best rooms in central Buyeo. Though this admittedly isn’t saying much, the place is spotless, with mood lighting in the rooms and piped music in the corridors.

041/832-3700. Near Boganso Rotary, with the best rooms in central Buyeo. Though this admittedly isn’t saying much, the place is spotless, with mood lighting in the rooms and piped music in the corridors.

Sky Motel  041/835-3331. Slightly cheaper than the VIP, this motel’s rooms are clean, airy and agreeably furnished; some have internet, for which you’ll pay about W5000 more. Look for the building with the stone-clad exterior.

041/835-3331. Slightly cheaper than the VIP, this motel’s rooms are clean, airy and agreeably furnished; some have internet, for which you’ll pay about W5000 more. Look for the building with the stone-clad exterior.

Busosan

Buyeo’s centre is dominated by its large fortress. Busosan ( ; March–Oct 7am–7pm; Nov–Feb 8am–5pm; W2000) lacks the perimeter wall of Gongju’s Gongsanseong, but with its position perched high over the Baengman River, plus a greater variety of trees and a thoroughly enjoyable network of trails, many visitors find this one even more beautiful. It also has history on its side, as this is where the great Baekje dynasty came to an end after almost seven centuries of rule.

; March–Oct 7am–7pm; Nov–Feb 8am–5pm; W2000) lacks the perimeter wall of Gongju’s Gongsanseong, but with its position perched high over the Baengman River, plus a greater variety of trees and a thoroughly enjoyable network of trails, many visitors find this one even more beautiful. It also has history on its side, as this is where the great Baekje dynasty came to an end after almost seven centuries of rule.

On entering the fortress, you’ll happen upon one of the many pavilions that dot the grounds, though the scattered nature of the trails mean that it’s neither easy nor advisable to see them all. Yeonggillu is nearest the entrance and has a particularly pleasant and natural setting; it’s also where kings brought local nobility for regular sunrise meetings, presided over by a pair of snakelike wooden dragons that remain today. Paths wind up to Sajaru, the highest point in the fortress and originally built as a moon-viewing platform. The path continues on to the cliff top of Nakhwa-am; from here, it is said, three thousand wives and daughters jumped to their deaths after General Gyebaek’s defeat by the Silla-Chinese coalition, choosing suicide over probable rape and servitude. This tragic act gave Nakhwa-am its name – Falling Flowers Rock – and has been the subject of countless TV epics. Down by the river is Goransa, a small temple backed by a spring that once provided water to the Baekje kings on account of its purported health benefits – servants had to prove that they’d climbed all the way here by serving the water with a distinctive leaf that only grew on a nearby plant. The spring water is said to make you three years younger for every glass you drink. The best way to finish a trip to the fortress is to take a ferry ride from a launch downhill from the spring. These sail a short way down the river to a sculpture park and some of the town’s best restaurants; in summer there’s a ferry every half-hour or so (W3000 one-way), but the service can be annoyingly infrequent in winter.

Heading south of Busosan’s main entrance, you might want to swing by Jeongnimsaji ( ; daily: March–Oct 7am–7pm; Nov–Feb 8am–5pm; W1000), a small but pretty site where a temple once stood. Several buildings here have been recreated, and you’ll also find a five-storey stone pagoda – one of only three survivors from Baekje times – and a seated stone Buddha dating back to the Goryeo era.

; daily: March–Oct 7am–7pm; Nov–Feb 8am–5pm; W1000), a small but pretty site where a temple once stood. Several buildings here have been recreated, and you’ll also find a five-storey stone pagoda – one of only three survivors from Baekje times – and a seated stone Buddha dating back to the Goryeo era.

Of more interest is Buyeo National Museum ( ; Tues–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat & Sun 9am–7pm; free), a large but slightly out-of-the-way place east of the city-centre statue of General Gyebaek. As with other “national” museums in Korea, it focuses exclusively on artefacts found in its local area; here there’s an understandable emphasis on Baekje riches. Some rooms examine Buyeo’s gradual shift from the Stone to the Bronze Age with a selection of pots and chopping implements, but inside a room devoted to Baekje treasures is the museum’s pride and joy – a bronze incense burner that has become the town symbol. Elaborate animal figurines cover the outer shell of this 0.6m-high egg-shaped sculpture, which sits on a base of twisted dragons; it’s considered one of the most beautiful Baekje articles ever discovered, displaying the dynasty’s love of form, detail and restrained opulence.

; Tues–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat & Sun 9am–7pm; free), a large but slightly out-of-the-way place east of the city-centre statue of General Gyebaek. As with other “national” museums in Korea, it focuses exclusively on artefacts found in its local area; here there’s an understandable emphasis on Baekje riches. Some rooms examine Buyeo’s gradual shift from the Stone to the Bronze Age with a selection of pots and chopping implements, but inside a room devoted to Baekje treasures is the museum’s pride and joy – a bronze incense burner that has become the town symbol. Elaborate animal figurines cover the outer shell of this 0.6m-high egg-shaped sculpture, which sits on a base of twisted dragons; it’s considered one of the most beautiful Baekje articles ever discovered, displaying the dynasty’s love of form, detail and restrained opulence.

A short walk south of General Gyebaek’s statue is Gungnamji ( ), a beautiful lotus pond with a pavilion at its centre, and surrounded by a circle of willow trees; outside this weepy perimeter lie acres of lotus paddies, making this peaceful idyll feel as if it’s in the middle of the countryside. To the east of town is a cluster of seven Baekje tombs (

), a beautiful lotus pond with a pavilion at its centre, and surrounded by a circle of willow trees; outside this weepy perimeter lie acres of lotus paddies, making this peaceful idyll feel as if it’s in the middle of the countryside. To the east of town is a cluster of seven Baekje tombs ( ); their history is relayed in a small information centre, though none of the former occupants are known for sure. A taxi from central Buyeo shouldn’t cost much more than W3000.

); their history is relayed in a small information centre, though none of the former occupants are known for sure. A taxi from central Buyeo shouldn’t cost much more than W3000.

Baekje Cultural Land

Across the river from Busosan, Baekje Cultural Land (daily 9am–5pm; W9000) opened in 2010, a large new facility intending to showcase the city’s dynastic history. Despite these noble intentions, it comes across as something of a rush-job, but it’s still just about worth the trek from central Buyeo (around W7000 by taxi). Near the entrance there’s an overlarge museum with absolutely nothing of historical interest inside, its curators choosing instead to bring ancient Baekje to life with a succession of cheesy dioramas. Just behind this brutal structure is a mock-Baekje palace, which is at least a little more in keeping with dynastic times; however, on closer inspection its reproduction buildings reveal themselves to be rather poorly painted, and the incessant piped music parping from innumerable speakers ruins the atmosphere somewhat. Best, perhaps, is the recreation of Wiryeseong, the first Baekje capital (which was actually inside present-day Seoul). Here you’ll find a clutch of thatch-roofed buildings, separated by dirt paths. Hunt around and you’ll find a small booth selling seafood pancakes ( ; haemul pajeon), drinks and simple snacks; other restaurants outside the complex include an excellent option inside the adjacent Lotte Resort.

; haemul pajeon), drinks and simple snacks; other restaurants outside the complex include an excellent option inside the adjacent Lotte Resort.

Eating

Food in Buyeo has similarities in style, content and quality with the cuisine of Jeolla province – expect plenty of side dishes, and more use of herbs and natural seasoning than is usual in typical Korean food. One fascinating place is  Minsokgwan (

Minsokgwan ( ), a traditionally styled restaurant with a courtyard full of old Korea paraphernalia, and tables and chairs inside fashioned from tree trunks. The naengmyeon (

), a traditionally styled restaurant with a courtyard full of old Korea paraphernalia, and tables and chairs inside fashioned from tree trunks. The naengmyeon ( ) – buckwheat noodles served in a cold, spicy soup – are good for cooling off in the summer, or try the home-made gimchi-tofu mix (

) – buckwheat noodles served in a cold, spicy soup – are good for cooling off in the summer, or try the home-made gimchi-tofu mix ( ). It’s on the road heading from Busosan to the ferry dock, and perhaps best accessed by taxi; if you go looking yourself, keep an eye out for a Chinese-language sign with a pair of stone turtles straining their necks towards it. Otherwise, try

). It’s on the road heading from Busosan to the ferry dock, and perhaps best accessed by taxi; if you go looking yourself, keep an eye out for a Chinese-language sign with a pair of stone turtles straining their necks towards it. Otherwise, try  Baekjeae-jip (

Baekjeae-jip ( ), on the main road just outside the fortress entrance; here you can have a gigantic set meal of leaves, duck meat (or beef, though duck is a local speciality) and innumerable side dishes, for around W10,000 per person.

), on the main road just outside the fortress entrance; here you can have a gigantic set meal of leaves, duck meat (or beef, though duck is a local speciality) and innumerable side dishes, for around W10,000 per person.

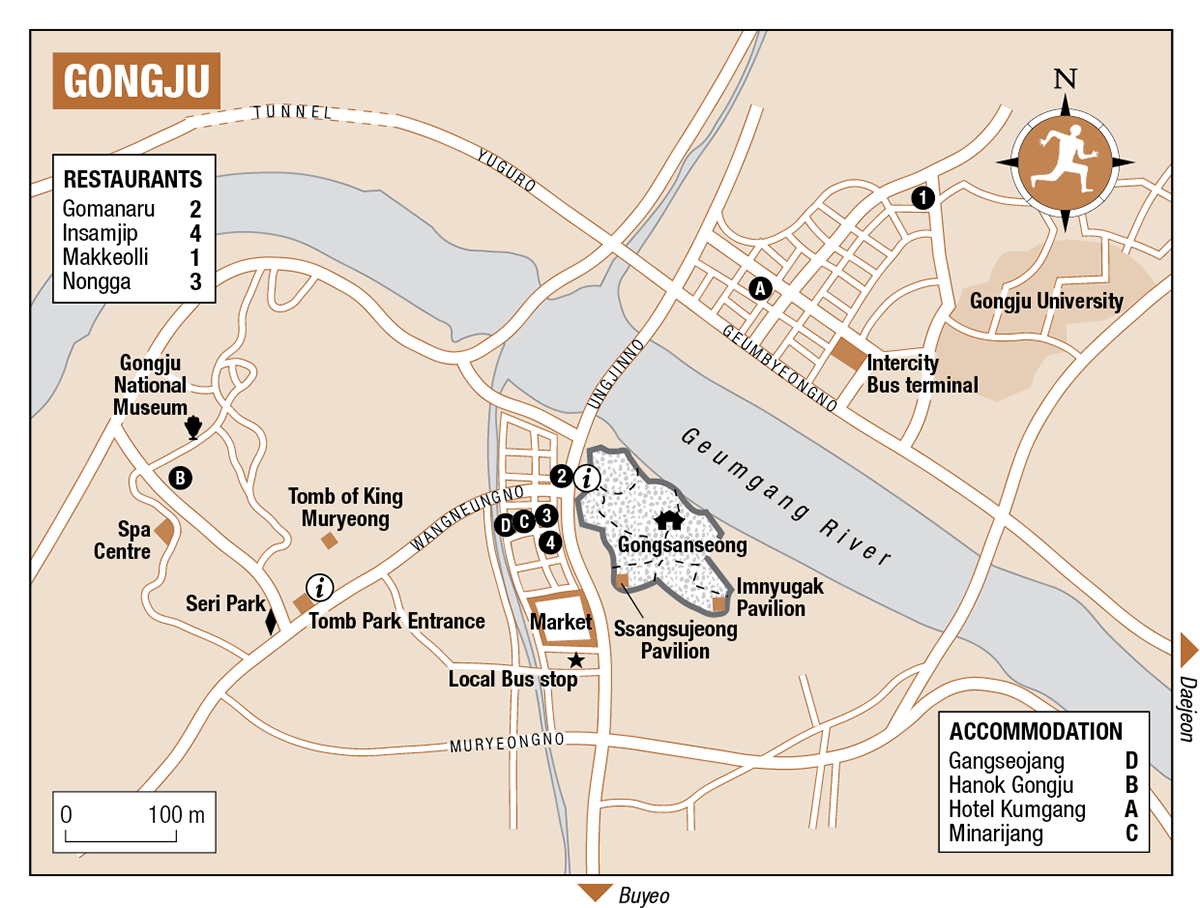

Presided over by the large fortress of Gongsanseong, small, sleepy GONGJU (

) is one of the most charming cities in the land, and deserving of a little more fame. It’s also the best place in which to see relics from the Baekje dynasty that it ruled as capital in the fifth and sixth centuries: King Muryeong, its most famous inhabitant, lay here undisturbed for over 1400 years, after which his tomb yielded thousands of pieces of jewellery that provided a hitherto unattainable insight into the splendid craft of the Baekje people. Largely devoid of the bustle, clutter and chain stores found in most Korean cities, and with a number of wonderful sights, Gongju is worthy of at least a day of your time.

) is one of the most charming cities in the land, and deserving of a little more fame. It’s also the best place in which to see relics from the Baekje dynasty that it ruled as capital in the fifth and sixth centuries: King Muryeong, its most famous inhabitant, lay here undisturbed for over 1400 years, after which his tomb yielded thousands of pieces of jewellery that provided a hitherto unattainable insight into the splendid craft of the Baekje people. Largely devoid of the bustle, clutter and chain stores found in most Korean cities, and with a number of wonderful sights, Gongju is worthy of at least a day of your time.

Arrival, information and city transport

Gongju is divided by the Geumgang River, with its small but spick-and-span new bus terminal just off the north bank. There are direct buses here from cities and towns across the Chungcheong provinces, as well as Seoul and other major Korean cities. The small local bus terminal near the fortress serves Gongju’s periphery. The main tourist information centre ( 041/856-7700; daily 9am–6pm; winter 9am–5pm), under Gongsanseong, usually has helpful, English-speaking staff.

041/856-7700; daily 9am–6pm; winter 9am–5pm), under Gongsanseong, usually has helpful, English-speaking staff.

Gongju’s small size means that it’s possible to walk between all of the sights listed here, with Gongsanseong a beautiful fifteen-minute walk from the terminal, along the river and over the bridge. Taxis are also cheap, with W4000 enough to get you anywhere in town.

Accommodation

Gongju’s poor range of accommodation is no doubt the main reason why the city has failed to attract international tourists, bar the occasional busloads of Japanese day-trippers from Seoul. Motels are centred in two areas: north of the river, to the west of the bus terminal, is a bunch of new establishments (including a couple of cheesy replica “castles”, looking over the Geumgang at a real one), while a group of older cheapies lie south of the river across the road from Gongsanseong. The latter is a quainter and more atmospheric area, and slightly closer to the sights, but the newer rooms are far more comfortable.

Gangseojang

041/853-8323. This red-brick, creekside yeogwan is the best option south of the river, and has decent-enough rooms; ask for the one with a computer terminal and free internet. Nearby, and also acceptable, is the similarly priced Minarijang.

041/853-8323. This red-brick, creekside yeogwan is the best option south of the river, and has decent-enough rooms; ask for the one with a computer terminal and free internet. Nearby, and also acceptable, is the similarly priced Minarijang.

Hanok Gongju  041/840-2763. A fairly decent recreation of a Baekje-era village (complete with café and convenience store), its wooden hanok buildings heated from beneath by burning wood. Rooms are spartan, for sure, but the location is relaxing, and the experience somewhat unique.

041/840-2763. A fairly decent recreation of a Baekje-era village (complete with café and convenience store), its wooden hanok buildings heated from beneath by burning wood. Rooms are spartan, for sure, but the location is relaxing, and the experience somewhat unique.

Hotel Kumgang

Hotel Kumgang  041/852-1071. The only official “hotel” in town, though in reality just a less-seedy-than-average motel with a few twin rooms to augment the doubles. However, it has friendly staff, spacious bathrooms, internet-ready computer terminals in most rooms and a moderately priced bar-restaurant on the second floor, and should suffice for all but the fussiest travellers.

041/852-1071. The only official “hotel” in town, though in reality just a less-seedy-than-average motel with a few twin rooms to augment the doubles. However, it has friendly staff, spacious bathrooms, internet-ready computer terminals in most rooms and a moderately priced bar-restaurant on the second floor, and should suffice for all but the fussiest travellers.

For centuries, Gongju’s focal point has been the hilltop fortress of Gongsanseong ( ; daily 9am–6pm; winter 9am–5pm; W1500), whose 2.6km-long perimeter wall was built from local mud in Baekje times, before receiving a stone upgrade in the seventeenth century. It’s possible to walk the entire circumference of the wall, a flag-pocked, up-and-down course that occasionally affords splendid views of Gongju and its surrounding area. The grounds inside are worth a look too, inhabited by stripey squirrels and riddled with paths leading to a number of carefully painted pavilions. Of these, Ssangsujeong has the most interesting history – where this now stands, a Joseon-dynasty king named Injo (ruled 1623–49) once hid under a couple of trees during a peasant-led rebellion against his rule; when this was quashed, the trees were made government officials, though sadly are no longer around to lend their leafy views to civil proceedings. Airy, green Imnyugak, painted with meticulous care, is the most beautiful pavilion; press on further west down a small path for great views of eastern Gongju. Down by the river there’s a small temple, a refuge to monks who fought the Japanese in 1592, and on summer weekends visitors have the opportunity to dress up as a Baekje warrior and shoot off a few arrows. Similarly traditional is a Baekje changing of the guard, which takes place at 2pm (April–June, Sept & early Oct). Lastly, note that two of Gongju’s best restaurants are a stone’s throw from the fortress entrance.

; daily 9am–6pm; winter 9am–5pm; W1500), whose 2.6km-long perimeter wall was built from local mud in Baekje times, before receiving a stone upgrade in the seventeenth century. It’s possible to walk the entire circumference of the wall, a flag-pocked, up-and-down course that occasionally affords splendid views of Gongju and its surrounding area. The grounds inside are worth a look too, inhabited by stripey squirrels and riddled with paths leading to a number of carefully painted pavilions. Of these, Ssangsujeong has the most interesting history – where this now stands, a Joseon-dynasty king named Injo (ruled 1623–49) once hid under a couple of trees during a peasant-led rebellion against his rule; when this was quashed, the trees were made government officials, though sadly are no longer around to lend their leafy views to civil proceedings. Airy, green Imnyugak, painted with meticulous care, is the most beautiful pavilion; press on further west down a small path for great views of eastern Gongju. Down by the river there’s a small temple, a refuge to monks who fought the Japanese in 1592, and on summer weekends visitors have the opportunity to dress up as a Baekje warrior and shoot off a few arrows. Similarly traditional is a Baekje changing of the guard, which takes place at 2pm (April–June, Sept & early Oct). Lastly, note that two of Gongju’s best restaurants are a stone’s throw from the fortress entrance.

The tomb of King Muryeong

Heading west over the creek from Gongsanseong, you’ll eventually come to the Tomb of King Muryeong ( ; daily 9am–6pm; W1500), one of many regal burial groups dotted around the country from the Three Kingdoms period, but the only Baekje mound whose occupant is known for sure. Muryeong, who ruled for the first quarter of the sixth century, was credited with strengthening his kingdom by improving relations with those in China and Japan; some accounts suggest that the design of Japanese jewellery was influenced by gifts that he sent across. His gentle green burial mound was discovered by accident in 1971 during a civic construction project – after one-and-a-half millennia, Muryeong’s tomb was the only one that hadn’t been looted. All have now been sealed off for preservation – the fact that you can’t peek inside is disappointing, but the sound of summer cicadas whirring in the trees, and the views of the rolling tomb mounds themselves, make for a pleasant stroll. A small exhibition hall contains replicas of Muryeong’s tomb and the artefacts found within. Opposite the entrance is Park Seri Park, a tiny patch of land dedicated to female golfer Seri Park, Gongju’s most famous citizen. Incidentally, another famous sporting Park also hails from Gongju – Major League pitcher Park Chan-ho.

; daily 9am–6pm; W1500), one of many regal burial groups dotted around the country from the Three Kingdoms period, but the only Baekje mound whose occupant is known for sure. Muryeong, who ruled for the first quarter of the sixth century, was credited with strengthening his kingdom by improving relations with those in China and Japan; some accounts suggest that the design of Japanese jewellery was influenced by gifts that he sent across. His gentle green burial mound was discovered by accident in 1971 during a civic construction project – after one-and-a-half millennia, Muryeong’s tomb was the only one that hadn’t been looted. All have now been sealed off for preservation – the fact that you can’t peek inside is disappointing, but the sound of summer cicadas whirring in the trees, and the views of the rolling tomb mounds themselves, make for a pleasant stroll. A small exhibition hall contains replicas of Muryeong’s tomb and the artefacts found within. Opposite the entrance is Park Seri Park, a tiny patch of land dedicated to female golfer Seri Park, Gongju’s most famous citizen. Incidentally, another famous sporting Park also hails from Gongju – Major League pitcher Park Chan-ho.

Gongju National Museum

To see the actual riches retrieved from Muryeong’s tomb head west to Gongju National Museum ( ; Tues–Sun 9am–6pm; free), set in a quiet wooded area by the turn of the river. Much of the museum is devoted to jewellery, and an impressive collection of Baekje bling reveals the dynasty’s penchant for gold, silver and bronze. Artefacts such as elaborate golden earrings show an impressive attention to detail, but manage to be dignified and restrained with their use of shape and texture. The highlight is the king’s flame-like golden headwear, once worn like rabbit ears on the royal scalp, and now one of the most important symbols not just of Gongju, but of the Baekje dynasty itself. Elsewhere in the museum exhibits of wood and clay show the dynasty’s history of trade with Japan and China.

; Tues–Sun 9am–6pm; free), set in a quiet wooded area by the turn of the river. Much of the museum is devoted to jewellery, and an impressive collection of Baekje bling reveals the dynasty’s penchant for gold, silver and bronze. Artefacts such as elaborate golden earrings show an impressive attention to detail, but manage to be dignified and restrained with their use of shape and texture. The highlight is the king’s flame-like golden headwear, once worn like rabbit ears on the royal scalp, and now one of the most important symbols not just of Gongju, but of the Baekje dynasty itself. Elsewhere in the museum exhibits of wood and clay show the dynasty’s history of trade with Japan and China.

Near the museum, you can relax at a small hot spring spa resort; the W5000 admission fee allows you entry to the pools and sauna facilities, and is a small price to pay to emerge clean and refreshed.

Food in Gongju is almost uniformly excellent, yet this wonderfully enjoyable facet of the city remains surprisingly off the radar, even for Korean tourists. The local specialities are duck meat ( ; ori-gogi), chestnuts (

; ori-gogi), chestnuts ( ; bam) and ginseng (

; bam) and ginseng (

; insam), and as in neighbouring Buyeo you’ll find your table festooned with even more side dishes than the national norm (which is already a lot). Another dish that deserves a mention is dog-meat soup (

; insam), and as in neighbouring Buyeo you’ll find your table festooned with even more side dishes than the national norm (which is already a lot). Another dish that deserves a mention is dog-meat soup ( ; bosintang), which may appeal to adventurous travellers; you’ll find plenty of places serving this dish around the local bus terminal. Two excellent restaurants, catering for more regular tastes, can be found near Gongsanseong; criminally, almost no places have a view over the river.

; bosintang), which may appeal to adventurous travellers; you’ll find plenty of places serving this dish around the local bus terminal. Two excellent restaurants, catering for more regular tastes, can be found near Gongsanseong; criminally, almost no places have a view over the river.

The area around Gongju University ( ), north of the main bus terminal, has some interesting places to drink, with the bar called Makkeolli a focal point; open until late and busiest during term-time, the full version of its name translates as something like “W10,000 can make you happy”, and the deceptively smooth rice wine certainly proves this point. Convenience stores, as well as the restaurants listed here, sell bottles of chestnut makkeolli (

), north of the main bus terminal, has some interesting places to drink, with the bar called Makkeolli a focal point; open until late and busiest during term-time, the full version of its name translates as something like “W10,000 can make you happy”, and the deceptively smooth rice wine certainly proves this point. Convenience stores, as well as the restaurants listed here, sell bottles of chestnut makkeolli ( ; W1800 in a shop, W5000 in a restaurant), a particularly creamy and delicious local take on the drink.

; W1800 in a shop, W5000 in a restaurant), a particularly creamy and delicious local take on the drink.

Gomanaru

Gomanaru  This unassuming restaurant is, quite simply, one of Korea’s most enjoyable places to eat. Here W10,000 per head (minimum two) will buy a huge ssam-bap (

This unassuming restaurant is, quite simply, one of Korea’s most enjoyable places to eat. Here W10,000 per head (minimum two) will buy a huge ssam-bap (

), which features a tableful of side dishes, and over a dozen kinds of leaves to eat them with. An extra W5000 will see the whole shebang covered with edible flowers – absolute heaven.

), which features a tableful of side dishes, and over a dozen kinds of leaves to eat them with. An extra W5000 will see the whole shebang covered with edible flowers – absolute heaven.

Insamjip  Although ginseng pops up in the side dishes at many Gongju restaurants, this place prides itself on the stuff: W5000 will get you a ginseng bibimbap, W6000 a galbi-tang (beef rib soup) infused with ginseng, and W7000 a full set meal where the “cure-all root” pops up in almost every dish.

Although ginseng pops up in the side dishes at many Gongju restaurants, this place prides itself on the stuff: W5000 will get you a ginseng bibimbap, W6000 a galbi-tang (beef rib soup) infused with ginseng, and W7000 a full set meal where the “cure-all root” pops up in almost every dish.

Nongga

Nongga  Like Gomanaru, this restaurant may not look like much, but the food is nothing short of superb. Everything on the menu features chestnut in some way; you’ll likely see the things being shelled by the charming local family who own the joint. W5000 will buy you a chestnut-and-seafood pancake (

Like Gomanaru, this restaurant may not look like much, but the food is nothing short of superb. Everything on the menu features chestnut in some way; you’ll likely see the things being shelled by the charming local family who own the joint. W5000 will buy you a chestnut-and-seafood pancake ( ), five huge chestnut dumplings (

), five huge chestnut dumplings ( ) or much more besides – an almost embarassingly low price for such delectable food.

) or much more besides – an almost embarassingly low price for such delectable food.

When passing through rural Chungcheong, those who’ve been travelling around Korea for a while may notice something special about the way locals talk. The pace of conversation here is slower than in the rest of the land (particularly the staccato patois of Gyeongsang province), with some locals speaking in a drawl that can even have non-native students of the language rolling their eyes and looking at their watches in frustration. One folk tale, retold across the nation, describes a Chungcheongese town that was destroyed by a falling boulder: apparently it was spotted early enough, but locals were unable to elucidate their warnings in a speedy enough manner.

Magoksa

A beautiful 45-minute bus ride through the countryside west of Gongju is Magoksa ( ; daily 8am–6pm; W3000). The exact year of this temple’s creation remains as mysterious as its remote, forested environs, but it’s believed to date from the early 640s. It is now a principal temple of the Jogye order, the largest sect in Korean Buddhism. Although the most important buildings huddle together in a tight pack, rustic farmyard dwellings and auxiliary hermitages extend into nearby fields and forest, and can easily fill up a half-day of pleasant meandering if you’re not temple-tired. The hushed vibe of the complex provides the main attraction, though a few of its buildings are worthy of attention. Yeongsanjeon (

; daily 8am–6pm; W3000). The exact year of this temple’s creation remains as mysterious as its remote, forested environs, but it’s believed to date from the early 640s. It is now a principal temple of the Jogye order, the largest sect in Korean Buddhism. Although the most important buildings huddle together in a tight pack, rustic farmyard dwellings and auxiliary hermitages extend into nearby fields and forest, and can easily fill up a half-day of pleasant meandering if you’re not temple-tired. The hushed vibe of the complex provides the main attraction, though a few of its buildings are worthy of attention. Yeongsanjeon ( ) is a hall of a thousand individually crafted figurines, and has a nameplate said to have been written by King Sejo (ruled 1455–68), a Joseon-dynasty monarch perhaps best famed for putting his brother to the sword. At the top of the complex, Daeungbojeon (

) is a hall of a thousand individually crafted figurines, and has a nameplate said to have been written by King Sejo (ruled 1455–68), a Joseon-dynasty monarch perhaps best famed for putting his brother to the sword. At the top of the complex, Daeungbojeon ( ) is a high point in more than one sense; the three golden statues in this main hall are backed by a large, highly detailed Buddhist painting, and look down on a sea of fish-scaled black roof tiles.

) is a high point in more than one sense; the three golden statues in this main hall are backed by a large, highly detailed Buddhist painting, and look down on a sea of fish-scaled black roof tiles.

Practicalities

Magoksa can be reached on buses #7 and #18 from the small terminal near the fortress in Gongju. On the way from the bus stop to the temple you’ll find a number of motels and restaurants, the best of which are the Magok Motel (

;

;  041/841-0047;

041/841-0047;  ), pretty swanky considering the rural location, and Gareung-binga (

), pretty swanky considering the rural location, and Gareung-binga ( ) just down the hill, a restaurant-cum-teahouse that serenades diners with traditional piped music.

) just down the hill, a restaurant-cum-teahouse that serenades diners with traditional piped music.

Despite its comparatively puny size relative to its Korean brethren, GYERYONGSAN NATIONAL PARK ( ) is a true delight, with herons flitting along the trickling streams, wild boar rifling through the woods and bizarre long net stinkhorn mushrooms – like regular mushrooms, but with a yellow honeycombed veil – found on the forest floors. It is said to have the most gi (

) is a true delight, with herons flitting along the trickling streams, wild boar rifling through the woods and bizarre long net stinkhorn mushrooms – like regular mushrooms, but with a yellow honeycombed veil – found on the forest floors. It is said to have the most gi ( ; life-force) of any national park in Korea, one of several factors that haul in 1.4 million people per year, making it the most visited national park in the Chungcheong region. The main reasons for this are accessibility and manageability – it lies equidistant from Gongju to the west and Daejeon to the east, and easy day-hikes run up and over the central peaks, connecting Gapsa and Donghaksa, two sumptuous temples that flank the park, both of which date back over a thousand years.

; life-force) of any national park in Korea, one of several factors that haul in 1.4 million people per year, making it the most visited national park in the Chungcheong region. The main reasons for this are accessibility and manageability – it lies equidistant from Gongju to the west and Daejeon to the east, and easy day-hikes run up and over the central peaks, connecting Gapsa and Donghaksa, two sumptuous temples that flank the park, both of which date back over a thousand years.

Zoom left

Zoom left

Arrival and accommodation

To get to the Gapsa entrance, take bus #2 from Gongju’s local bus terminal. Another #2 bus runs here from Daejeon’s Yuseong terminal, meaning that – unbelievably – there are only two buses serving Gapsa, both of which have the same number. From Daejeon, bus #107 runs from Yuseong to the Donghaksa entrance every fifteen minutes or so.

The bulk of Gyeryongsan’s rooms (and restaurants) are around the bus terminal below Donghaksa, but not all are of high quality; the Gapsa end is prettier and more relaxed. Donghak Sanjang ( ;

;  042/825-4301;

042/825-4301;  ) has average rooms but is right above the Donghaksa bus terminal and consequently one of the first to sell out. Nearby is a campsite (from W3000 per tent). Below Gapsa are some very rural minbak (

) has average rooms but is right above the Donghaksa bus terminal and consequently one of the first to sell out. Nearby is a campsite (from W3000 per tent). Below Gapsa are some very rural minbak ( ), while on the other side of the car park is an achingly sweet village of

), while on the other side of the car park is an achingly sweet village of  traditional houses with simple rooms for rent – at night the cramped, yellow-lit alleyways create a scene that is redolent of a bygone era, and make for a truly atmospheric stay. Rooms go from W20,000, but hunt around to find the best and try to haggle the price down. There’s also a youth hostel in the Gapsa area (

traditional houses with simple rooms for rent – at night the cramped, yellow-lit alleyways create a scene that is redolent of a bygone era, and make for a truly atmospheric stay. Rooms go from W20,000, but hunt around to find the best and try to haggle the price down. There’s also a youth hostel in the Gapsa area ( 041/856-4666; dorms W15,000), which is as soulless as others around the country.

041/856-4666; dorms W15,000), which is as soulless as others around the country.

The temples

Gapsa ( ) is the larger and more enchanting of the pair, its beauty enhanced further when surrounded by the fiery colours of autumn – maple and ginkgo trees make a near-complete ring around the complex, and if you’re here at the right time you’ll be treated to a joyous snowfall of yellow and red. It was established in 420, during the dawn of Korean Buddhism, though needless to say no extant structures are of anything approaching this vintage.

) is the larger and more enchanting of the pair, its beauty enhanced further when surrounded by the fiery colours of autumn – maple and ginkgo trees make a near-complete ring around the complex, and if you’re here at the right time you’ll be treated to a joyous snowfall of yellow and red. It was established in 420, during the dawn of Korean Buddhism, though needless to say no extant structures are of anything approaching this vintage.

On the other side of the park entirely, and connected to Gapsa with umpteen hiking trails, Donghaksa ( ) is best accessed from Daejeon and is said to look at its most beautiful in the spring. It has served as a college for Buddhist nuns since 724, and its various buildings exude an air of restraint (though some have, sadly, been renovated without much care).

) is best accessed from Daejeon and is said to look at its most beautiful in the spring. It has served as a college for Buddhist nuns since 724, and its various buildings exude an air of restraint (though some have, sadly, been renovated without much care).

Although the temples are pretty, most visitors to the park are actually here for the hike between them – two main routes scale the ridge and both should have you up and down within four hours, including rests; given the terrain, it’s slightly easier to hike east to west if you have a choice. Heading in this direction, most people choose to take the path that runs up the east side of Donghaksa, which takes in a couple of ornate stone pagodas on its way to Gapsa. Others take a faster but more challenging route south of the temple, which heads up the 816m-high peak of Gwaneumbong; these two routes are connected by a beautiful ridge path that affords some excellent views. Whichever way you go, routes are well signposted in Korean and English, though the tracks can get uncomfortably busy at weekends; a less crowded (and much tougher) day-hike runs from Byeongsagol ticket booth – on the road north of the main eastern entrance to the park – to Gwaneumbong, taking in at least seven peaks before finally dropping down to Gapsa.

Eating

Local ajummas will go out of their way to lure you into their establishments. The best restaurants are on a leafy streamside path running parallel to the main Donghaksa access road, where – as at other Korean national parks – gamjajeon (

; potato pancake) and dongdongju (

; potato pancake) and dongdongju ( ; milky rice wine) are the order of the day. There’s also an excellent streamside

; milky rice wine) are the order of the day. There’s also an excellent streamside  teahouse just below Gapsa temple, with a variety of teas for W4000 – in winter the bitter saenggang-cha (

teahouse just below Gapsa temple, with a variety of teas for W4000 – in winter the bitter saenggang-cha ( ; ginger tea) is hard to beat. It had closed at the time of writing, but with luck this gorgeous venue will have reopened before too long.

; ginger tea) is hard to beat. It had closed at the time of writing, but with luck this gorgeous venue will have reopened before too long.

Daejeon

Every country has a city like DAEJEON ( ) – somewhere pleasant to go about daily life, but with little to offer the casual visitor. These, however, arrive in surprisingly high numbers, many using the city as a default stopover on the high-speed rail line from Seoul to Busan. There are far better places in which to break this journey, including on the lesser-used slow line through Danyang, Andong and Gyeongju, but if you do choose to hole up in Daejeon you’ll find a few mildly diverting attractions. Most vaunted are Expo Park, built for an exposition in 1993 yet still somehow a source of local pride, and Yuseong, the therapeutic hot-spring resort on the western flank of the city. Daejeon’s best use, perhaps, is as a base for the small but pretty Gyeryongsan to the west.

) – somewhere pleasant to go about daily life, but with little to offer the casual visitor. These, however, arrive in surprisingly high numbers, many using the city as a default stopover on the high-speed rail line from Seoul to Busan. There are far better places in which to break this journey, including on the lesser-used slow line through Danyang, Andong and Gyeongju, but if you do choose to hole up in Daejeon you’ll find a few mildly diverting attractions. Most vaunted are Expo Park, built for an exposition in 1993 yet still somehow a source of local pride, and Yuseong, the therapeutic hot-spring resort on the western flank of the city. Daejeon’s best use, perhaps, is as a base for the small but pretty Gyeryongsan to the west.

Arrival and information

Daejeon has excellent bus connections to every major city in the country, though arrivals are often hampered by the city’s incessant traffic. Rather confusingly, there are three main bus terminals: buses from most Chungcheong destinations arrive at the Seobu terminal to the south of the city, while the other two – the express (gosok) terminal and the intercity Dongbu terminal – sit across the road from each other to the northeast. The city also has two train stations: Daejeon station is right in the centre and sits on the Seoul–Busan line, while Seodaejeon station is a W3000 taxi-ride away to the west, sitting on a line that splits off north of Daejeon for Gwangju and Mokpo. Daejeon station has an excellent tourist information office on the upstairs departure level (daily 9am–6pm;  042/221-1905), which can help out with accommodation or bus routes; there’s a slightly less useful one outside the express bus terminal.

042/221-1905), which can help out with accommodation or bus routes; there’s a slightly less useful one outside the express bus terminal.

City transport

The city’s size and the amount of traffic makes getting around frustrating. The city bus network is comprehensive but complicated, with hundreds of routes – two of the most useful are #841, which connects Daejeon station to all three bus terminals, and #107, which runs from the express terminal via Yuseong to Gyeryongsan. Given the traffic it may be better to head from Daejeon station to Yuseong by subway, on the line that bisects the city, running past Dunsandong’s bars on the way; tickets come in the form of cute blue plastic tokens, and cost W900.

Accommodation

Finding a place to stay shouldn’t be too much trouble, though don’t expect much in the centre – the higher-end lodgings are all way out west in Yuseong, the default base for the city’s many business visitors. Many of these squat over hot springs, the mineral-heavy waters coursing up into bathrooms and communal steam rooms; non-guests can usually use the latter for a fee (W6000–25,000). The city centre’s main motel areas are notoriously sleazy, particularly the one surrounding the bus terminals. Pickings are even slimmer in Eunhaengdong, the area west of the main train station, but if you come out of the main exit and turn right onto the side street before the main road, you’ll come across a warren of near-identical yeoinsuk – bare rooms with communal showers and squat toilets set around courtyards, but dirt-cheap at W10,000.

Bijou Motel Eunhaengdong  042/254-6603. Across the main road from the train station (to the right of the T-junction as seen from the exit), this is an acceptable lower-end choice, with clean and cheerily decorated en-suite rooms.

042/254-6603. Across the main road from the train station (to the right of the T-junction as seen from the exit), this is an acceptable lower-end choice, with clean and cheerily decorated en-suite rooms.

Carib Theme Motel Yuseong  042/823-8800. Just around from the Legend, this is one of the best cheap sleeps in Yuseong. Ask to see a few rooms – some have internet, some are carpeted, and some even trump the upmarket hotels with steam saunas.

042/823-8800. Just around from the Legend, this is one of the best cheap sleeps in Yuseong. Ask to see a few rooms – some have internet, some are carpeted, and some even trump the upmarket hotels with steam saunas.

Legend Yuseong

Legend Yuseong  042/822-4000,

042/822-4000,  www.legendhotel.co.kr. The cheapest and friendliest of Yuseong’s top hotels, the stylish Legend gives five-star service at four-star prices. Rooms are decked out in relaxing tones, and there’s an on-site restaurant and spa.

www.legendhotel.co.kr. The cheapest and friendliest of Yuseong’s top hotels, the stylish Legend gives five-star service at four-star prices. Rooms are decked out in relaxing tones, and there’s an on-site restaurant and spa.

Motel Bobos Express Bus Terminal area. The zone around the main bus terminals is awash with sleazy motels, and this is no exception, but rooms here are the cushiest in the area.

Hotel Riviera Yuseong  042/823-2111,

042/823-2111,  www.hotelriviera.co.kr. The plushest hotel in the city features Japanese and Chinese restaurants, as well as a stylish lounge bar, and is large enough to seem quiet most of the time. The rooms have been pleasantly decorated and have internet, though not all have bathtubs.