North Korea

Highlights

The Mass Games Unquestionably one of the most spectacular events you’ll ever see – try to time your visit to coincide with it if at all possible.

Kumsusan Memorial Palace Pay a visit to the father of the nation, who lies in state beyond a labyrinthine warren of corridors, elevators and moving walkways.

Ryugyong Hotel Rising 105 stories into the Pyongyang sky, this half-finished mammoth is off-limits to tourists and impossible to miss; it may soon reopen as one of the world’s largest hotels.

Monumental Pyongyang The largest granite tower in the world and a colossal bronze effigy of the “Great Leader” are just a few of the capital’s larger-than-life sights.

Pyongyang subway Though only two stations are usually accessible to foreigners, most will get a kick out of the depth and design of these palaces of the proletariat.

The DMZ Get a slightly different take on the Korean crisis during a visit to the northern side of the world’s most fortified frontier.

North Korea

Espionage, famine and nuclear brinkmanship; perpetrator-in-chief of an international axis of evil; a rigidly controlled population under the shadowy rule of a president long deceased... you’ve heard it all before, but North Korea’s dubious charms make it the Holy Grail for hard-bitten travellers. A trip to this tightly controlled Communist society is only possible as part of an expensive package, but a high proportion of those fortunate and intrepid enough to visit rank it as their most interesting travel experience.

North Korea is officially known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or the DPRK. However, real democracy is thin on the ground, and comparisons with the police state in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four are impossible to avoid: in addition to a regime that acts as a single source of information, residents of Pyongyang, and many other cities, do indeed wake up to government-sent messages and songs broadcast through speakers in their apartments, which can be turned down but never off – the fact that this is often the cue for callisthenic exercises further strengthens associations with the book. (Messages are also often relayed into many South Korean apartments, though these tend to be about garbage disposal and missing children, and the speakers can be turned off.) Other Big Brother similarities include verified claims that the country is crawling with informants, each seeking to further his or her own existence by denouncing friends, neighbours or even family for such crimes as letting their portrait of the Great Leader gather dust, singing unenthusiastically during a march, or simply being related to the wrong person. Also true is the rumour that locals have to wear a pin-badge portraying at least one of the leaders – Kim Il-sung, the country’s inaugurator and “Great Leader”, and the “Dear Leader”, his eldest son Kim Jong-il. Interestingly, Kim Il-sung remains the country’s official president, despite having died in 1994. Both Kims are revered almost as gods, by a people with precious little choice in the matter.

For all this, North Korea exerts a unique appeal for those willing and able to visit. Whether you’re looking out over Pyongyang’s oddly barren cityscape or eating a bowl of rice in your hotel restaurant, the simple fact that you’re in one of the world’s most inaccessible countries will bring an epic feel to everything you do. It’s also important to note the human aspect of the North Korean machine. Behind the Kims and their carefully managed stage curtain live real people leading real lives, under severe financial, nutritional, political and personal restrictions unimaginable in the West. Thousands upon thousands have found conditions so bad that they’ve risked imprisonment or even death to escape North Korea’s state-imposed straightjacket. All the more surprising, then, that it’s often the locals who provide the highlight of a visit to the DPRK – many, especially in Pyongyang, are extremely happy to see foreign visitors, and you’re likely to meet at least a couple of people on your way around, whether it’s sharing an outdoor galbi meal with a local family, chatting with the staff at your hotel, or saluting back to a marching gaggle of schoolchildren. This fascinating society functions in front of an equally absorbing backdrop of brutalist architecture, bronze statues, red stars and colossal murals, a scene just as distinctive for its lack of traffic, advertising or Western influence.

A visit to North Korea will confirm some of the things you’ve heard about the country, while destroying other preconceptions. One guarantee is that you’ll leave with more questions than answers.

Busting myths

A lot has been said and written about the current situation in North Korea, much of it true. These crazy truths, however, make it awfully easy to paint rumours, assumptions and hearsay as cast-iron fact. Political falsehoods have been detailed by excellent authors such as Cumings, Winchester and Oberdorfer, who take both sides’ views into account, but a few of the more straightforward rumours can be easily debunked.

The first great untruth to put to bed is that North Koreans are somehow evil; whatever their leader’s state of mind, remember that the large majority of the population have no choice whatsoever in the running of the country or even their own lives, much less than other populations that have found themselves under authoritarian rule. Another myth is that you’ll be escorted around by a gun-wielding soldier; it’s true that you’ll have guides with you whenever you’re outside the hotel, but they’re generally very nice people and it’s occasionally possible to slip away for a few minutes.

Sometimes even the myths are myths. The tale of Kim Jong-il hitting eleven holes in one on his first-ever round of golf is bandied about in the West as evidence of mindless indoctrination; the so-called rumour itself is actually unheard of in North Korea.

The Democratic Republic of Korea was created in 1948 as a result of global shifts in power following the Japanese defeat in World War II and the “The Korean War” that followed. The Korean War, which ended in 1953, left much of the DPRK in tatters; led by Kim Il-sung, a young, ambitious resistance fighter from Japanese annexation days, the DPRK busied itself with efforts to haul its standard of life and productive capacity back to prewar levels. Kim himself purged his “democratic” party of any policies or people that he deemed a threat to his leadership, fostering a personality cult that lasts to this day. Before long, he was being referred to by his people as Suryong, meaning “Great Leader”, and Tongji, a somewhat paradoxical term describing a higher class of comrade (in North Korea, some comrades are evidently more equal than others). He also did away with the elements of Marxist, Leninist or Maoist thought that did not appeal to him, preferring instead to follow ““The Juche idea””, a Korean brand of Communism that focused on national self-sufficiency. For a time, his policies were not without success – levels of education, healthcare, employment and production went up, and North Korea’s development was second only to Japan’s in East Asia. Its GDP-per-head rate actually remained above that of South Korea until the mid-1970s.

The American threat never went away, and North Koreans were constantly drilled to expect an attack at any time. The US Army had, in fact, reneged on a 1953 armistice agreement by reintroducing nuclear weapons into South Korea, and went against an international pact by threatening to use such arms against a country that did not possess any; North Korea duly got to work on a reactor of their own at Yongbyon.

There were regular skirmishes both around the DMZ and beyond, including an attack on the “USS Pueblo” in 1968, assassination attempts on Kim Il-sung and South Korean president Park Chung-hee around the same time, and the famed ““The Axe Murder Incident”” that took place in the Joint Security Area in 1976. During the 1970s at least “The Third Tunnel of Aggression” were discovered heading “The North Korea tour”, which undetected could have seen KPA forces in Seoul within hours.

Decline to crisis

Then came the inevitable decline – Juche was simply not malleable enough as a concept to cope with external prodding or poor internal decision-making. Having developed into a pariah state without parallel, North Korea was forced to rely on the help of fellow Communist states – the Soviet Union and China, which was busy solving problems of its own under the leadership of Chairman Mao. The economy ground almost to a halt during the 1970s, while in the face of an American-South Korean threat that never diminished, military spending remained high. It was around this time that Kim Jong-il was being groomed as the next leader of the DPRK – the Communist world’s first dynastic succession.

During the 1990s North Korea experienced alienation, famine, nuclear threats and the death of its beloved leader. The break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991 nullified North Korea’s greatest source of funds, and a country officially extolling self-sufficiency increasingly found itself unable to feed its own people. Despite the nuclear crisis with the US the DPRK was making a few tentative moves towards peace with the South; indeed, it was just after examining accommodation facilities prepared for the first-ever North-South presidential summit that Kim Il-sung suffered a heart attack and died. This day in July 1994 was followed by a long period of intense public mourning – hundreds of thousands attended his funeral, in Pyongyang, and millions more paid their respects around the country – after which came a terrible famine, a period known as the “Arduous March”. Despite being dead, Kim Il-sung was elected “Eternal President”, though his son, Kim Jong-il, eventually assumed most of the duties that require the authorization of a living body, and was made Supreme Commander of the army.

Say this about North Korea’s leaders: they may be Stalinist fanatics, they may be terrorists, they may be building nuclear bombs, but they are not without subtlety. They have mastered the art of dangling Washington on a string.

David Sanger, New York Times, March 20, 1994

Since the opening of a reactor at Yongbyon in 1987, North Korea has kept the outside world guessing as to its nuclear capabilities, playing a continued game of bluff and brinkmanship to achieve its aims of self-preservation and eventual reunification with the South. The folding of the Soviet Union in 1991 choked off much of the DPRK’s energy supply; with few resources of their own, increasing importance was placed on nuclear energy, but the refusal to allow international inspectors in strengthened rumours that they were also using the facilities to create weapons-grade plutonium. Hans Blix and his crew at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) were finally permitted entry in 1992, but were refused access to two suspected waste disposal sites, which would have provided strong evidence about whether processed plutonium was being created or not; Blix was, however, shown around a couple of huge underground facilities that no one on the outside even knew about. North Korea was unhappy with the sharing of information between American intelligence (the CIA) and the independent IAEA, but after threatening to withdraw from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) they agreed in 1994 to freeze their programme in exchange for fuel. This only happened after an election within the White House – Bill Clinton was more willing to compromise than his predecessor George Bush Senior. North Korea continued to do itself no favours, at one point launching a missile into the Sea of Japan in 1993 (though this was actually a failed attempt at launching a satellite, it was seen by many as practice for a future attack).

The second part of the crisis erupted more suddenly. In 2002, after making veiled threats about a possible resumption of their nuclear programme, North Korea abruptly booted out IAEA inspectors. Coming at the start of the war in Afghanistan, the timing was risky to say the least, but Pyongyang skated even closer to the line by admitting not only to having nuclear devices (and claiming that it did not know how to dismantle them), but also to being willing to sell them on the world market. All of these were bargaining ploys aimed at getting George W. Bush’s administration to follow the “Sunshine Policy” pursued by Clinton and Kim Dae-jung. Regular six-party talks between China, Russia, Japan, the US and the two Koreas achieved little, and in 2006 North Korea conducted its first nuclear test, and sent another missile into the Sea of Japan. North Korea had shown it had yet another card up its sleeve, and talks continued with greater candour. In July 2007 Pyongyang finally announced that it was shutting down its Yongbyon reactor in exchange for aid, and its permanent disability was confirmed by international inspectors two months later.

The Sunshine Policy

The year 1998 brought great changes to North-South relations. Kim Dae-jung was elected president of South Korea, and immediately started his “Sunshine Policy” of reconciliation with the North, which aimed for integration without absorption (assimilation having been the main goal of both sides up until this point). With US president Bill Clinton echoing these desires in the White House, all three sides seemed to be pulling the same way for the first time since the Korean War. The two Kims held a historic Pyongyang summit in 2000, the same year in which Kim Dae-jung was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The southern premier revealed to the Western media that Kim Jong-il actually wanted the American army to remain in the South (to keep the peace on the peninsula, as well as for protection from powerful China and an ever more militarist Japan), as long as Washington accepted North Korea as a state and pursued reconciliation over confrontation. Clinton was actually set for a summit of his own in Pyongyang, but the election of George W. Bush in 2000 put paid to that. Bush undid many of the inroads that had been made, and antagonized the DPRK, famously labelling it part of an “Axis of Evil” in 2002.

The second nuclear crisis, in 2002, brought about a surprise admission from the North – Japanese prime minister Junichiro Koizumi went across for a summit expecting to be forced into saying sorry for Japanese atrocities during occupation. Instead it was Kim Jong-il who did the apologizing, astonishingly admitting to a long-suspected series of kidnappings on the Japanese coast in the late 1970s and early 1980s, ostensibly as a rather convoluted way of teaching his secret service personnel Japanese. Though the number of abductions was probably higher, Kim admitted to having taken thirteen people, of whom eight had died; one of the survivors had married Charles Robert Jenkins, an American defector from the post-Korean War period. The belief that more hostages were unaccounted for – and possibly still alive – made it impossible for Koizumi to continue his policy of engagement with the DPRK.

In 2002 Roh Moo-hyun was elected South Korean president, and adhered to the precepts of the Sunshine Policy. While the course under his tenure was far from smooth – the US and the DPRK continued to make things difficult for each other, South Korean youth turned massively against reunification, and Roh himself suffered impeachment for an unrelated issue – there was some movement, however, notably the symbolic reopening of train lines across the DMZ in 2007.

Return to crisis

In 2008, a South Korean tourist was killed after entering a high-security area on a visit to the Geumgang mountains. Seoul suspended these cross-border trips, choking off a much-needed source of income for Pyongyang, who eventually confiscated all South Korean-owned property in the area. Tension remained high until 2010, when two catastrophic incidents brought inter-Korean relations to a postwar low. First came the “The sinking of the Cheonan, and the Yeonpyeongdo attacks”, a South Korean naval vessel; this was followed later in the year by the shelling of the West Sea island of “The sinking of the Cheonan, and the Yeonpyeongdo attacks”, and retaliatory attacks by the South. At the time of writing, the situation remained extremely tense, with full-on military confrontation a distinct possibility.

The North Korean capital of PYONGYANG ( ) could credibly claim to be the most unsettling city on the face of the earth. This city of empty streets, lined with huge grey monuments and buildings, and studded with bronze statues and murals in honour of its idolized leaders, is a strange concrete and marble experiment in socialist realism. It stands as a showcase of North Korean might, with its skyscrapers and wide boulevards giving a faint echo of Le Corbusier’s visions of utilitarian urban utopia: every street, rooftop, doorway and windowsill has been designed in keeping with a single grand vision. On closer inspection, however, you’ll notice that the buildings are dirty and crumbling, and the people under very apparent control.

) could credibly claim to be the most unsettling city on the face of the earth. This city of empty streets, lined with huge grey monuments and buildings, and studded with bronze statues and murals in honour of its idolized leaders, is a strange concrete and marble experiment in socialist realism. It stands as a showcase of North Korean might, with its skyscrapers and wide boulevards giving a faint echo of Le Corbusier’s visions of utilitarian urban utopia: every street, rooftop, doorway and windowsill has been designed in keeping with a single grand vision. On closer inspection, however, you’ll notice that the buildings are dirty and crumbling, and the people under very apparent control.

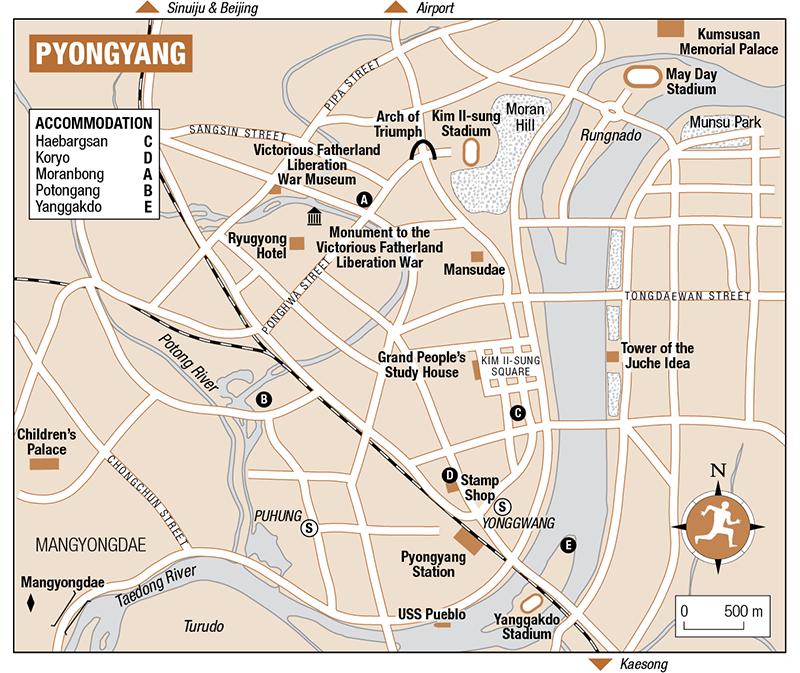

Pyongyang’s near three million inhabitants live a relatively privileged existence. Life here is far better than in the countryside, though you’ll still see signs of poverty: power cuts are commonplace, and each evening the city tumbles into a quiet darkness hard to fathom in a capital city. There’s also next to no visible commerce – the city is entirely devoid of the billboards and flashy lights commonplace in a metropolis of this size; instead socialist realist murals form the only advertising, and vie for attention with the Communist slogans screamed in red from the tallest buildings. You’ll be taken by bus around a selection of officially sanctioned sights. These include Kumsusan Memorial Palace, where the body of Kim Il-sung lies in state, and Mansudae, his colossal statue; the distinctive granite Juche Tower overlooking the Taedong River; and the Pyongyang metro, one of the world’s most intriguingly secretive subway systems. Pyongyang is also the venue for the amazing Mass Games, which take place at the May Day Stadium. However, all sights aside, whether you’re simply eating at a restaurant or relaxing in your hotel, Pyongyang is always fascinating.

Arrival and information

Most visitors to Pyongyang are here to start a guided excursion, so whether you arrive by plane or train – your only two options – a bus or private car will be waiting, ready to whisk you to your hotel. The twenty-minute journey from the airport to central Pyongyang is a fascinating one for first-time visitors, displaying an impoverishment that the authorities have made surprisingly little effort to conceal. The road is in good condition but usually empty, save for occasional pedestrians on their way to or from work, and the countryside rather barren. Those disembarking at the far more central train station will have to settle for urban views. Given the tightness of the average itinerary, you’re likely to visit at least one sight before checking in at your hotel.

There’s no tourist information office in North Korea, but your guide will be on hand to answer any questions. Most topics are fine, but asking anything that could be construed as disparaging of the regime could land you or your host in hot water. The guides are usually amiable, though at some sights you’ll be in the hands of specialists employed to bark out nationalistic vitriol (which, you’ll notice, increases in force and volume when either of the Kims are mentioned).

The spectacular Mass Games are among the world’s must-see events. Also known as the “Arirang Games”, they take place in Pyongyang’s 150,000-seater May Day Stadium – though this is always full to bursting, unbelievably there are always more performers than there are spectators. Wildly popular with foreign tourists, the show is actually created for local consumption – this is a propaganda exercise extraordinaire, one used by the West as evidence of a rigidly controlled population in thrall to the Kim dynasty.

Even the warm-up will fill you with wonder, awe and trepidation. Your entry to the stadium is serenaded by upwards of twenty thousand schoolchildren; filling the opposite stand, they scream out in perfect unison while flashing up the names of their schools on large coloured flipbooks, effectively forming human pixels on a giant TV screen that remains an ever-changing backdrop throughout the show. The performers themselves come out in wave after wave, relaying stories about the hardships under Japanese occupation, the creation of the DPRK, and the bravery in the face of American aggression, as well as less bombastic parables about farming life or how to be safe at the seaside. Among the cast will be thousands-strong teams of chosonbok-wearing dancers, ball-hurling schoolkids and miniskirt-wearing female “soldiers” wielding rifles and swords, their every move choreographed to a colourful perfection. The form of the displays changes – military-style marches give way to performances of gymnastics or traditional dance, and the cast are at one point illuminated in brilliant blue, forming a rippling sea. Visitors are often left speechless – you’ll just have to see for yourself..

City transport

Getting around the city is usually as simple as waking up in time to catch your tour bus (those left behind will be stuck in the hotel until their group returns). Pyongyang’s crammed public buses and trams are for locals only, and your guides would think you crazy to want to use them when you already have paid-for private transport, but if you have any say in your schedule be sure to ask for a ride on the “Pyongyang subway”. The buses themselves are pretty photogenic, many of the Hungarian relics from the 1950s; look out for the stars on their sides, as each one represents fifty thousand accident-free kilometres.

Traffic ladies

While Pyongyang does have a few traffic lights dotted around its rather empty streets, these eat up energy in a country not blessed with a surplus of power – step forward the traffic ladies. Chosen for their beauty by the powers-that-be, and evidently well schooled, they direct the traffic with super-fast precision, in the middle of some of the busier intersections, and sport distinctive blue (sometimes white) jackets, hats and skirts, as well as regulation white socks. The traffic ladies are rather popular with some visitors, and one or two tour groups have persuaded their guides to stop by for a brief photo-shoot.

There are fewer than a dozen hotels in Pyongyang designated for foreigners, and which one you end up at will be organized in advance by your tour operator. Most groups stay at Pyongyang’s top hotels, the Koryo and Yanggakdo; there’s little between them in terms of service and quality. Both provide a memorable experience and are tourist draws in their own right, which is a good thing, considering the amount of time you’ll be spending there – in the evening, when your daily schedule is completed, there’s not really anywhere else to go. Note that the colossal Ryugyong was under development at the time of writing.

Haebangsan This is the cheapest hotel for foreigners, and a recent renovation has made it a perfectly acceptable place to stay – at least in warmer months, since 24-hour running water is not guaranteed. Another drawback is a near-total lack of atmosphere or on-site activities.

Koryo Hotel The salmon-pink twin towers of the Koryo sit on a main thoroughfare, making for a much better appreciation of local life than is possible in the Yanggakdo. Rooms at this forty-storey hotel are well kept and the on-site restaurants passable, while the ground-floor mini-market – stocked with foreign drinks, biscuits and other comestibles – is the best place in the city to sate Western sugar cravings. If you are on an independent tour you can request trips to nearby restaurants or the Swiss co-venture bakery-cum-café across the road.

Moranbong A boutique hotel in Pyongyang – whatever next? There are just twelve rooms here, and the fitness centre and pool exude an atmosphere rather contrary to the rest of the country. However, it’s popular with diplomats and as such a little hard to book.

Potonggang Just west of central Pyongyang, in a dull part of town, the Potonggang is the only hotel to feed a couple of American TV channels into the rooms. Despite the acceptable facilities, few Westerners end up staying here; if you do, you’ll find it hard to miss the huge Kim mural in the lobby.

Yanggakdo This 47-storey hotel sits on an islet in the Taedong, and commands superb views of both the river and the city from its clean, spacious rooms. The isolated location means that you’ll be able to wander around outside without provoking the ire of guides or guards, though to be honest there’s precious little to do. The on-site restaurants are excellent, with one that revolves slowly at the top of the tower, which is a great place for a nightcap. The ground-floor bar brews its own beer, which is quite delicious after a hard day slogging around sights. Also on site are a bowling alley, a karaoke room and a tailor.

The Ministry of Truth – Minitrue, in Newspeak – was startlingly different from any other object in sight. It was an enormous pyramidal structure of glittering white concrete, soaring up, terrace after terrace, three hundred metres into the air... the Ministry of Truth contained, it was said, three thousand rooms above ground level, and corresponding ramifications below.

George Orwell Nineteen Eighty-Four

It’s somewhat ironic that North Korea’s most distinctive building seems to have had its design lifted from the pages of Ninteen Eighty-Four, a book banned across the country. In a Pyongyang skyline dominated by rectangular apartment blocks, the Ryugyong Hotel is the undisputed king of the hill – a bizarre triangular fusion of Dracula’s castle and the Empire State building. Despite the fact that it sticks out like a sore and rather weathered thumb, a whole generation of locals have viewed it as a taboo subject – this was something that couldn’t be painted over with the regular whitewash of propaganda.

Construction of the pyramidal 105-floor structure started in 1987, a mammoth project intended to showcase North Korean might. The central peak was to be topped with a revolving restaurant, while the two lower cones may have held smaller versions of the same. For a time, Pyongyang was one of only three cities in the world that could boast a hundred-storey-plus building, the others being New York and Chicago. Kim Il-sung had expected the Ryugyong to become one of the world’s most admired hotels, its near-3000 rooms filled with awestruck tourists. But no sooner had the concrete casing been completed than the (largely French) funding fell through, and the project was put on indefinite hold. It was left empty, a mere skeleton devoid of electricity, carpeting and windows.

Work only recommenced in earnest in 2008. By 2010, the crane that had maintained a lonely, sixteen-year vigil atop the structure had disappeared, and most of the naked exterior had finally been covered with tinted windows. It’s scheduled to reopen for Kim Il-sung’s 100th birthday bash in 2012 (as, it seems, is everything else in the land), but for now you’re not allowed to enter its immediate area – those who have the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Square on their schedules will get quite near. This is one of the city’s largest ongoing projects, so it seems that before too long the world’s largest shell will become one of its most distinctive places to stay.

The huge Kumsusan Memorial Palace is a North Korean cathedral, labyrinth, palace and Mecca all rolled into one, and the single most important place in the country. It’s here that the body of Kim Il-sung lies in state, though only invitees are allowed to see it – you’ll witness a lot of high-ranking military proudly wearing their medals and stripes. The official residence of Kim Il-sung until his death in 1994, it was transformed into his final resting place under the orders of his son and heir, Kim Jong-il. While perceived disrespect to the Great Leader isn’t advisable anywhere in the country, it will not be tolerated here – be on your best behaviour, dress smartly and keep any conversation hushed.

The walk around the palace and past Kim Il-sung is a long, slow experience, one that usually takes well over an hour. Security is understandably tight – you’ll be searched at the entrance and told to leave cameras, coats and bags at reception. Then starts the long haul through corridor after marble corridor, some of which are hundreds of metres long; thankfully, moving walkways are in place, but stand on them, rather than walk – it’s an experience to be savoured, and you’re likely to see several locals, even the butchest of soldiers, in tears. One room is filled with reliefs and friezes of the Korean people mourning the loss of their leader; here you’ll be handed an mp3 guide, complete with earphones, for an English-language lecture, one delivered in a posh, quavering voice and as bombastic as they come – “just as the sun burns itself to give light and heat to the universe, so did President Kim Il-sung devote himself wholeheartedly to the Juche cause”. Be prepared for this: Kumsusan is not the place in which to be struck by a fit of the giggles.

After accessing an upper floor by elevator, your proximity to Kim’s body will be heralded by a piped rendition of the “Song of General Kim Il-sung”, composed after his death. Absolute silence is expected as visitors pass into the main room, bathed in a dim red light. A queue circles around the illuminated body – follow the North Korean lead, and take a deep bow on each side.

After paying your respects, you’ll be ushered through more corridors. In one room are Kim’s many medals, prizes, doctorates and awards – note that a few of the universities on his dozens of diplomas have never existed. Then it’s past a wall-map of the world showing the countries that Kim visited, and the train carriage and car that he did some of his travelling in. After collecting your things you’ll usually be allowed out onto the main square for a much-needed stroll.

At Mansudae, west of the river, a huge bronze statue of Kim Il-sung stands in triumph, backed by a mural of Mount Paekdu – spiritual home of the Korean nation, and lifting a benevolent arm to his people. Unlike the mausoleum, this is not actually a memorial, but was cast when Kim was still alive: a sixtieth birthday present to himself, paid for by the people and monies donated by the Chinese government (Beijing was said to be unhappy with the unnecessary extravagance of the original gold coating, and it was soon removed). So important is the statue that, despite its size – a full 20m – it’s given a thorough scrub at least once a week. The respect given by North Korean visitors to the statue is also expected of foreigners: each individual, or every second or third person if it’s a large tour party, will have to lay flowers at the divine metal feet (these will be bought on the walk towards the monument, and you may be asked to chip in). Each group must also line up and perform a simultaneous bow – stay down for at least a few seconds. Note that taking any pictures that might be deemed “offensive”, which includes those cutting part of the statue off or pretending to support Kim as you might the Leaning Tower of Pisa, may result in your camera being confiscated.

Sloping up from the monument is Moran Hill, a small park crisscrossed with pleasant paths, and used by city-dwellers as a place to kick back and relax. While there’s nothing specific to see, those who visit on a busy day will get a chance to see North Korean life at first hand – this is one of the best places in the country to make a few temporary friends. A simple smile, wave or greeting (in Korean, preferably) has seen travellers invited to scoff bulgogi at a picnic or dance along to traditional tunes with a clutch of chuckling grannies.

The Arch of Triumph

The huge white granite Arch of Triumph, at the bottom of Moran Hill, is on almost every tourist itinerary; you may even be taken here before checking in to your hotel. Modelled on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, but deliberately built a little higher than its French counterpart, it’s the largest such structure in the world. The arch was completed in 1982 to commemorate Korea’s resistance to Japan, whose occupation ended in 1945. Despite the fact that it was actually Soviet forces that liberated the city, the on-site guide will tell you that Kim Il-sung did all the hard work. Though these erroneous contentions are absorbing, if you’re part of a larger group you may prefer to sidestep the spiel for a stroll around the area. Just a minute’s walk away, and easily visible from the arch, is a tremendous mural of the Great Leader receiving the adulation of his public, while set further back is the 100,000-seater Kim Il-sung Stadium; don’t venture too close to the latter unless you want to receive reprimanding whistles from folk in uniforms. There’s also a small theme park nearby, which features on some itineraries; a recent overhaul, replete with imported equipment, has made this one of the city’s most enjoyable attractions.

A resident’s view of life in Pyongyang

“We in Pyongyang are pretty lucky – life here is much better than in the countryside. As elsewhere, our apartments are provided to us by the government, and we don’t pay rent. Most people have a TV and a refrigerator, some have a washing machine, and quite a few now have a computer; these are usually secondhand units from Europe or China. Actually, kids have been getting into chatting on the internet, but it’s not possible to contact people outside the country, and sometimes the whole network goes down for weeks or even years at a time, the same as for our mobile telephones. We all hate it when that happens.

“I guess our educational system is pretty similar to other countries. We have club activities after lessons, usually sports, and we can study foreign languages at school – English is the most popular, followed by Russian. One thing people won’t get outside our country is teachings on the ‘Three Revolutions’: these are ideology – that’s the most important one – culture and technology. Kim Jong-il says that technology is important if we are to progress, so lots of people want to study it at university now. Kim Il-sung University is the biggest, with maybe twelve thousand students, but there are other ones around the country; the one in Wonsan, for example, is pretty famous for economics. Military service is compulsory for boys, who have to do three years, and girls can join as volunteers.

“In my free time I like to listen to music, and sing it too, of course. Like lots of people I go to a sports club – football, basketball and fishing are popular, but I like volleyball more, so that’s what I do. It’s also pretty common to rent movies; we can get American films from the rental store as well as local ones, but nothing really political. Men like to drink beer – they get five litres per month from the government in vouchers, and often go to the bar straight after work. This makes them drunk before they come home for dinner, which makes a lot of our women really angry.”

Anon

Kim Il-sung Square and around

West of the Taedong River is Kim Il-sung Square, a huge paved area where the sense of space is heightened by its near-total lack of people. First-time visitors may also get a sense of déjà vu – it’s in all the stock North Korean footage of goose-stepping soldiers that is shown whenever the country is in the news (incidentally this act is far from a daily event, and not even an annual one – it’s only performed on important military anniversaries). State propaganda peers down into the square from all sides in the form of oversized pictures and slogans. The message on the party headquarters on the north side of the square reads “Long live the Democratic People’s Republic of Choson!” Others say “With the Revolutionary Spirit of Paekdu Mountain!” and “Follow the Three Revolutionary Flags!” – the red flags in question read “history”, “skill” and “culture”, and are being reared away from by Chollima, a winged horse of Korean legend. Visible to the east across the river is the soaring flame-like tip of the Juche Tower. At the west of the square is the Grand People’s Study House, effectively an oversized library and one of the few buildings in the city to be built with anything approaching a traditional style – a little ironic, considering its status as a vault of rewritten history. This isn’t on all tour itineraries, but anyone given the chance to enter will doubtless be impressed by the super-modern filing system.

A local take on Marxist-Leninist theory, Juche is the official state ideology of the DPRK, and a system that informs the decision-making of each and every one of its inhabitants. Though Kim Il-sung claims the credit for its invention, the basic precepts were formed by yangban scholars in the early twentieth century, created as a means of asserting Korean identity during the Japanese occupation. The basic principle is one of self-reliance – both nation and individual are intended to be responsible for their own destiny. Kim Il-sung introduced Juche as the official ideology in the early 1970s, and the doctrines were put to paper in 1982 by his son Kim Jong-il in a book entitled On the Juche Idea. Foreign-language editions are available at hotels in Pyongyang, though the core principle of the treatise is as follows:

...man is a social being with independence, creativity and consciousness, which are his social attributes formed and developed in the course of social life and through the historic process of development; these essential qualities enable man to take a position and play a role as master of the world.

As one local puts it, “Juche is more centred around human benefit than material gain relative to the theories of Marx or Lenin. There’s no time for asking why we don’t have something, or excusing yourself because of this absence... if the state doesn’t provide something, make it yourself!” In spite of this apparent confidence, there are some pretty serious flaws and contradictions evident in the DPRK’s pursuit of its own creed – the country preaches self-reliance but has long been heavily dependent on the international community for aid, and though Juche Man is said to be free to make his own decisions, democracy remains little more than a component part of the state’s official title.

Despite the all-too-apparent failings of North Korea’s interpretation of the theory, Juche managed to sow seeds abroad – Pol Pot and Ceaucescu borrowed heavily from the philosophy, though neither achieved much success, a lesson for Kim Jong-il, perhaps.

Tower of the Juche Idea

While the Mansudae Grand Monument was Kim Il-sung’s 60th birthday gift to himself, the Tower of the Juche Idea is what he unwrapped when he turned 70 in 1982, a giant, 150m-high candle topped with a 20m red flame, rising up from its site on the banks of the Taedong River. Named after the North Korean take on Communist theory it’s the tallest granite tower in the world, and one of the few points of light in Pyongyang’s dim night sky. A kind of socialist version of Cheomseongdae in the South, but without the astrological capabilities, it is made out of 25,550 granite slabs – one for each day of Kim’s 70 years.

It’s possible to take a lift to the torch-level for stupendous views over Pyongyang. You could choose to stay behind, citing a fear of heights, for a guide-free walk around the area: the two guides will have to go up with your group, leaving you alone to wander the riverside park; given the slug-like speed of the lift, this may be some time.

The Children’s Palace

Behind their strained faces, you sense all the concentration that goes into playing the music, and especially into trying to keep up those Miss World smiles…It’s all so cold and sad. I could cry.

Guy Delisle, Pyongyang

The Children’s Palace showcases the impressive talents of some of the most gifted youths in the country – you’ll be escorted from room to room, taking in displays of everything from volleyball and gymnastics to embroidery and song. For some visitors, this by-product of Kim Il-sung’s contention that “children are the treasure of the nation” is a sweet and pleasant part of the tour, for others the atmosphere can be more than a little depressing – while there’s no denying the abilities of the young performers, it’s hard to dispel the level of intensity required in their training. At the end of the tour is an impressive but brutally regimental performance of song and dance in the large auditorium, showcasing North Korean expertise to foreign guests, but many leave wondering what the country would be like if similar efforts were put into more productive educational pursuits.

Many visitors find it incredible that a country as poor as North Korea has something as decadent as a functioning subway system ( www.pyongyang-metro.com), one that even has two lines; in fact, there are likely to be several more for government-only use, though details are kept well under wraps. Only two of the sixteen known stations – Puhung and Yonggwang – are open to foreign visitors (though Koryo Tours has access rights for a full six), a fact that has led some reporters to declare that no more exist. Some even claim that North Korean passengers on the line are nothing more than actors who shuffle onto the trains, only to reappear minutes later on the other platform, but a visit of your own should put paid to these notions.

www.pyongyang-metro.com), one that even has two lines; in fact, there are likely to be several more for government-only use, though details are kept well under wraps. Only two of the sixteen known stations – Puhung and Yonggwang – are open to foreign visitors (though Koryo Tours has access rights for a full six), a fact that has led some reporters to declare that no more exist. Some even claim that North Korean passengers on the line are nothing more than actors who shuffle onto the trains, only to reappear minutes later on the other platform, but a visit of your own should put paid to these notions.

The first thing you’ll notice is the length of the escalator; Pyongyang has some of the world’s deepest subway platforms, said to be reinforced and deep enough to provide protection to the Pyongyang masses in the event of a military attack. Marble-floored, with sculpted columns and bathed in the dim glow of low-wattage chandelier lights, these platforms look surprisingly opulent, and are backed by large socialist realist mosaics. The trains themselves are a mix of Chinese rejects and relics of the Berlin U-Bahn, the latter evident in the occasional bit of ageing German graffiti; all feature the obligatory Kim pictures in each carriage.

The journey between stations doesn’t last long, but will give you the chance to make a little contact with the locals. Photos of the subway or the boards that mark it from the outside – “ji” ( ) in Korean text, short for jihacheol – go down particularly well with South Koreans, most of whom are totally unaware that such a facility exists in the North.

) in Korean text, short for jihacheol – go down particularly well with South Koreans, most of whom are totally unaware that such a facility exists in the North.

A piece of history floating on the Taedong River, the USS Pueblo would count as a Pyongyang must-see were it not for the fact that you’ll probably have to see it anyway. On January 23, 1968, this small American research ship was boarded and captured by KPA forces in the East Sea – whether it was in North Korean or international waters at the time depends on whom you ask. The reasons for the attack, in which one crew member was killed, also vary from one side to the other – the North Koreans made accusations of espionage, the Americans contend that Stalin wanted an on-board encryptor – as do accounts of what happened to the 83 captured crew during their enforced stay in the DPRK; the misty cloak of propaganda makes it hard to verify tales of torture, but they’re equally difficult to reject. What’s known for sure is that Pyongyang spent months waiting for an apology which the Americans deferred for months, and it was only on December 23 that the crew finally crossed to safety over Panmunjom’s “Bridge of No Return”.

You’ll be ushered into the ship, part of which has been converted into a tiny cinema, and shown a short documentary. This is fascinating, and states the North Korean position on the matter in no ambiguous terms, showing how well the prisoners were kept, then reprimanding these “brazen-faced American aggressors” for failing to turn around to salute their captors on crossing at Panmunjom. A uniformed “soldier” will then escort you through the rest of the ship, pointing out bullet holes and the like, before escorting you back onto dry land.

The museums

North Korean tours once revolved around Pyongyang’s surprisingly large number of museums. Tour companies have mercifully wised up to the fact that most travellers would prefer simply to stroll down a city street than be bombarded with hours of national triumph and foreign aggression, and consequently the average number of museum visits has been pared down to two or three. There are few better windows into the “official” national mentality, or what’s taught at school across the land.

If you have any say in your schedule, make sure that it includes a visit to the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum. Right from the huge, cheery mural at the entrance, you’ll be subjected to the most fervent America-bashing that you’re likely to hear in North Korea; the terms “aggressors”, “imperialists” and “imperialist aggressors” are used avidly. You’ll be escorted through rooms filled with photos and documents relating to atrocities said to have been inflicted on Korea by the Americans, many of which were apparently seized after the liberation of Seoul during the Korean War. The important bits on the documents are underlined, which helps to steer the eye away from some suspiciously shoddy English – however obvious forgeries may be (and there are some), don’t be tempted to point it out, and just treat it as part of the game. The tour then continues to the basement, which is full of war machinery including several bullet-ravaged planes, a torpedo ship and some captured guns and trucks. Of most interest is a helicopter shot down over North Korean territory; next to the vehicle’s carcass is an extraordinary photograph of the pilot surrendering next to his dead buddy. From here you then move on to the panorama room, where the scenery slowly revolves around a central platform. This depiction of a battle in the Daejeon area is spectacular, having been rendered on an apparently seamless 15m x 132m length of canvas.

Mangyongdae

A visit to Mangyongdae – the purported birthplace of Kim Il-sung on April 15, 1912 – is almost guaranteed to feature on your itinerary. Despite the lack of things to see, the park-like area is pretty in a dull sort of way, and kept as modest as possible, its wooden buildings surrounded by greenery and meandering paths providing a nod to Kim’s peasant upbringing. You’ll likely be offered spring water from the on-site well, which supposedly gets visitors “into the revolutionary spirit of things”. The nearby funfair is marginally more interesting, and features a coconut shy where you can hurl projectiles at targets dressed up as American and Japanese soldiers.

Eating and drinking

As with accommodation, all your dining requirements will be sorted out in advance. North Koreans seem to think that foreigners will only enjoy their meal if they’re rotating slowly – both the Koryo and Yanggakdo hotels have revolving restaurants. Contrary to many reports, others do exist in Pyongyang; in fact, there’s one on almost every block, but many are camouflaged by their lack of signage and rather hard to spot (the locals know where to go and almost all are off-limits to outsiders, so there’s no need for a sign). The best places, however, are closed to all but foreigners and the party elite, and you’ll probably eat at a different one on each day of your stay.

Two of the most popular restaurants are Pyongyang Best Barbecued Duck, which serves this and not much else, and the Chongnyu, which specializes in Korean hotpot. Those staying at the Koryo should ask to be taken to Pyolmori, a nearby café-cum-bakery part-owned by a Swiss group – in addition to tasty snacks, they serve what’s undoubtedly the best coffee in the country.

You usually have breakfast in your hotel, and on some days will also have lunch or dinner there. Both the volume and the quality of food will depend on the prevailing food situation at the time of your visit – experienced diplomats suggest that the fare seems to improve when big groups or important folk are in town. Lastly, those visiting in warmer months may spot ladies selling ice cream from tiny booths. There’s usually only one variety – a creamy stick-bar called an Eskimo – but the real appeal for many is the opportunity to get some North Korean money as change.

Drinking can be one of Pyongyang’s most unexpected delights – while you won’t exactly be painting the town red, many travellers stagger to bed from the hotel bar absolutely sozzled every single night of their stay (and then have to get up at 7am to catch the tour bus). The Koryo and Yanggakdo are both topped with revolving restaurants, which become bars of an evening – perfect for a nightcap with a view of Pyongyang’s galaxy of faint lights. The Yanggakdo has a nightclub, as well as a ground-floor bar churning out draught beer and stout from an on-site microbrewery.

Other sights in the DPRK

Most of the country is closed off to foreign visitors, but even the shortest tour itinerary is likely to contain at least one sight outside Pyongyang. The most common trip is to Panmunjom in the DMZ, via Kaesong, the closest city to the border, but there are other popular excursions to Paekdusan, the mythical birthplace of the Korean nation and its highest peak, and the wonderful “Diamond Mountains” of Kumgangsan near the South Korean border. If you do venture further than Pyongyang, you’ll witness poverty-stricken North Korea at first hand – in the capital there’s little to remind you of its Third World status, but outside things are extremely different, and this is only the poverty you’re allowed to see. You’ll also notice a notable change in the locals’ reaction to your presence: whereas a smile or wave may be reciprocated in Pyongyang, elsewhere you may invoke trepidation.

Other than Pyongyang, KAESONG ( ) is usually the only North Korean city that foreign travellers get to see. From the capital, it’s an easy ninety-minute trip south along the traffic-free Reunification Highway; the road actually continues all the way to Seoul, just 80km away, though it’s blocked by the DMZ a few kilometres south of Kaesong. Its proximity to the border means the surrounding area is armed to bursting and crawling with soldiers, and it’s hardly surprising that Kaesong’s long-suffering citizens often come across as a little edgy. The city itself is drab and grimy in comparison with Pyongyang, but offers a far more accurate reflection of “typical” North Korean life.

) is usually the only North Korean city that foreign travellers get to see. From the capital, it’s an easy ninety-minute trip south along the traffic-free Reunification Highway; the road actually continues all the way to Seoul, just 80km away, though it’s blocked by the DMZ a few kilometres south of Kaesong. Its proximity to the border means the surrounding area is armed to bursting and crawling with soldiers, and it’s hardly surprising that Kaesong’s long-suffering citizens often come across as a little edgy. The city itself is drab and grimy in comparison with Pyongyang, but offers a far more accurate reflection of “typical” North Korean life.

Despite the palpable tension, Kaesong – romanized as “Gaeseong” in the South – is actually a place of considerable history: this was once the capital of the Goryeo dynasty, which ruled over the peninsula from 936 to 1392, though thanks to wholesale destruction in the Korean War, you’ll see precious little evidence of this today. One exception is Sonjuk Bridge, which was built in the early thirteenth century; it was here that an eponymous Goryeo loyalist was assassinated as his dynasty fell. The one sight guaranteed to catch the eye is somewhat more modern – a huge statue of Kim Il-sung. One of the most prominent such statues in the country, and even visible from the Reunification Highway on the way to Panmunjom, it’s illuminated at night come what may owing to its own generator, which enables it to surf the crest of any power shortages that afflict the rest of the city.

There are a few officially sanctioned sights in Kaesong’s surrounding countryside. West of the city on the road to Pyongyang is the tomb of the unfortunately named Wang Kon, the first leader of Goryeo and the man responsible for moving the dynasty’s capital to Kaesong, his home town. In the South, he’s more commonly known as King Taejo, and his decorated grass-mound tomb is similar to those that can be found in Seoul. Further west is another tomb, this one belonging to Wang Jon. Also known as King Kongmin, he ruled (1351–74) during Mongol domination of the continent; in keeping with the traditions of the time, he married a Mongol princess and was buried alongside her – the tiger statues surrounding the tomb represent the Goryeo dynasty, while the sheep are a nod to the Mongol influence. North of Wang Kon’s tomb is Pakyon, a forest waterfall whose surroundings include a fortress gate and a beautiful temple.

Groups heading to or from Panmunjom often have a lunch stop in Kaesong; the unnamed restaurant favoured by most tour leaders lays on a superb spread, apportioned into little golden bowls. It’s also possible to stay in Kaesong, which is an interesting add-on to many tours – the Kaesong Folk Hotel is a parade of traditional rooms running off a courtyard, the complex dotted with swaying trees and bisected by a peaceful stream. Rooms are basic, and sometimes fall victim to power outages, but it’s a unique experience with an entirely different vibe from the big hotels in Pyongyang.

Special excursions

This section details a few of the most common DPRK sights outside Pyongyang. All regularly feature on tour itineraries, but new areas are opened up from time to time – this is largely thanks to Koryo Tours, who take a hugely proactive stance in these regards.

Haeju A great side-trip for history buffs: the city is home to a huge pavilion erected in 1500, while the surrounding area is home to a Goryeo-dynasty mountain fortress and a Joseon-era Confucian academy. It’s possible to stay the night here.

Hamheung Major east coast city, only opened to tourism in 2010 – your presence will cause quite a stir. It’s visually interesting, with lots of buildings designed by East German architects, while attractions include factory tours and trips to local farms.

Kumgangsan Just north of the DMZ, and within a ninety-minute drive of Wonsan, this has long been regarded as the most beautiful mountain range on the peninsula. It was once open to South Korean tourists, but for now the only way in is from the North. You’ll be able to take in a few beautiful lakes – one of these, Sijungho, has a guesthouse whose spa offers mud treatments.

Nampo A major city just 45 minutes west of Pyongyang by bus. Sights are low-key, but interesting in their own way – most visitors get shown around the 8km-long West Sea Barrage, the steelworks and a couple of factories. Ask for a trip to the hot springs resort.

Wonsan A large port city – visitors usually get shown around the docks, though more interesting is the chance to swim in the sea at Songdowon Beach, just down the coast. On the way to or from Pyongyang (a four-hour drive) you may be able to stop at the gorgeous Ulim waterfalls – ask permission for a dip, if it’s warm.

Do I hate Americans? Not really – I don’t like the policies of their government or military, but that’s no reason to hate the people. Our Dear Leader himself has American friends – have you heard of Billy Graham? We don’t have many Americans on this tour, but I always make a special effort to please them; in fact, I stay in touch with a couple as pen-pals. One of my dreams is that Korea will reunify, and then I can meet them again, either here or in their own country.

North Korean soldier, Joint Security Area

The village of PANMUNJOM ( ) sits bang in the middle of the Demilitarized Zone that separates North and South Korea. You’ll see much the same from the North, but with the propaganda reversed – all of a sudden it was the US Army that started the Korean War and Kim Il-sung who won it. Interestingly, many visitors note that the cant is just as strong on the American side (though usually more balanced).

) sits bang in the middle of the Demilitarized Zone that separates North and South Korea. You’ll see much the same from the North, but with the propaganda reversed – all of a sudden it was the US Army that started the Korean War and Kim Il-sung who won it. Interestingly, many visitors note that the cant is just as strong on the American side (though usually more balanced).

The route to Panmunjom follows the Reunification Highway from Kaesong. Your first stop will be at the KPA guardpost, which sits just outside the northern barrier of the DMZ; the southern flank and the democracy beyond are just 4km away, though it feels far further than that. Here you’ll see a wonderful hand-painted picture of a boy and girl from each side savouring unification, but for some reason the guards aren’t keen on people taking photos of it. After being given a short presentation of the site by a local soldier, it’s back onto your bus for the ride to the DMZ itself – note the huge slabs of concrete at the sides of the road, ready to be dropped to block the way of any invading tanks (this same system is in place on the other side). A short way into the DMZ is the Armistice Hall, which was cobbled together at incredible speed by North Korean soldiers to provide a suitable venue for the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement, a document which brought about a ceasefire to the Korean War on July 27, 1953. Tucked away in a corner is what is said to be the weapon from the famed “Axe Murder Incident”, an incident for which North Korea claims little responsibility.

From the Armistice Hall you are taken to the Joint Security Area, where Panmun Hall – which, whatever the American soldiers on the other side might say, is a real, multilevel building of more than a couple of metres in depth – looks across the border at a South Korean building of similar size.You may even see a few tourists being escorted around. From here, you’re taken into one of the halls that straddle the official line of control, and are permitted to take a few heavily guarded steps into South Korean territory. The whole experience is bizarre, but fascinating, and an oddly tranquil place, despite its status as one of the world’s most dangerous border points.

Many of the same DMZ rules apply, whichever side you’re coming from – dress smartly, refrain from gesticulating to the other side, and don’t go off on your own. It’s possible to pop briefly across the official border, but it almost goes without saying that you won’t be allowed to go any further. If you time it right, you could even hit the border from both sides within a few days, and stand in almost exactly the same square metre without having had any hope of crossing immediately to the other side: such is the nature of the Korean conflict.

In 1998 a section of the Kumgangsan mountains in North Korea was bought on a long-term lease by Hyundai Asan, a wing of the gigantic Hyundai corporation which was in charge of various cross-border business ventures. Its head, Chung Mong-hun – the son of tycoon Chung Ju-yung, Hyundai’s founder – found himself accused of illegally shifting hundreds of millions of dollars to Kim Jong-il’s coffers. The secret payments centred around the first summit between the leaders of North and South Korea, which took place in 2000 and eventually landed the South Korean president, Kim Dae-jung, the Nobel Peace Prize; it didn’t help that the North seemed to be using at least some of these funds to recommence work on their Yongbyon nuclear reactors. Chung Mong-hun was eventually indicted in what became known as the “Cash-for-summit” scandal; disgraced and heading for prison, he leapt to his death from his high-level office on August 4, 2003.

Kumgangsan

Before partition, the KUMGANGSAN ( ) mountain range – which sits just north of the DMZ on Korea’s east coast – was widely considered to be the most beautiful on the peninsula. The DPRK’s relative inaccessibility has ensured that this remains the case. Spectacular crags and spires of rock tower over a skirt of pine-clad foothills, its pristine lakes and waterfalls adding to a richly forested beauty rivalled only by Seoraksan just across the border. There are said to be more than twelve thousand pinnacles, though the principal peak is Birobong, which rises to 1638m above sea level.

) mountain range – which sits just north of the DMZ on Korea’s east coast – was widely considered to be the most beautiful on the peninsula. The DPRK’s relative inaccessibility has ensured that this remains the case. Spectacular crags and spires of rock tower over a skirt of pine-clad foothills, its pristine lakes and waterfalls adding to a richly forested beauty rivalled only by Seoraksan just across the border. There are said to be more than twelve thousand pinnacles, though the principal peak is Birobong, which rises to 1638m above sea level.

Kumgangsan can be visited as part of a North Korean tour, and was indeed once visitable on a trip from South Korea (where it’s spelt “Geumgangsan”, but pronounced the same); the area could almost be viewed as the “Republic of Hyundai”, having been leased for controlled tourism by the South Korean business behemoth, but at the time of writing their properties north of the border had been confiscated, and tours put on indefinite hold.

Myohyangsan

Many North Korean tours include a visit to MYOHYANGSAN ( ), a pristine area of hills, lakes and waterfalls around 150km north of Pyongyang. Though it’s about as close as the DPRK comes to a mountain resort, the reason to come here isn’t to walk the delightful hiking trails, but to visit the International Friendship Exhibition – a colossal display showing the array of presents given to the Kims by overseas well-wishers. After the exhibition you’re likely to be taken to see Pohyonsa, an eleventh-century temple just a short walk away, and Ryongmun or Paengryong, two stalactite-filled limestone caves that burrow for a number of kilometres under the surrounding mountains.

), a pristine area of hills, lakes and waterfalls around 150km north of Pyongyang. Though it’s about as close as the DPRK comes to a mountain resort, the reason to come here isn’t to walk the delightful hiking trails, but to visit the International Friendship Exhibition – a colossal display showing the array of presents given to the Kims by overseas well-wishers. After the exhibition you’re likely to be taken to see Pohyonsa, an eleventh-century temple just a short walk away, and Ryongmun or Paengryong, two stalactite-filled limestone caves that burrow for a number of kilometres under the surrounding mountains.

Should your schedule allow for an overnight stay, you’re likely to find yourself at the pyramidal Hyangsan Hotel; this is currently the best hotel in the country, with an on-site health complex and stupendous pool, as well as the obligatory top-floor revolving restaurant.

The International Friendship Exhibition

The halls of the International Friendship Exhibition burrow deep into a mountainside – insurance against any nuclear attacks that come the DPRK’s way. Indeed, such is the emphasis on preservation that you’ll be forced to don a pair of comically oversized slippers before you enter the halls. The combination of highly polished granite floors and friction-lite footwear makes it incredibly tempting to take off down the corridors like a speed skater, but this would be looked on as a sign of immense disrespect and is therefore cautioned against. Inside the exhibition hall, gifts numbering 200,000 and rising have been arranged in order of country of origin, the evident intention being to convince visitors that Kim Sr and Kim Jr command immense respect all over the world – of course, this is not the place to air any painful truths. Mercifully, you won’t have to see all of the presents, though even the officially edited highlights can become a drag.

The first rooms you come to are those dedicated to Kim Il-sung. For a time, gifts were pouring in from all over the Communist world, including a limousine from Stalin and an armoured train carriage from Chairman Mao. There are also a number of medals, tea sets, pots, cutlery and military arms, as well as more incongruous offerings such as fishing rods and a refrigerator. Next you’ll be ushered into a room featuring a life-size wax statue of the great man; local visitors bestow on this exhibit all the respect they would on Kim himself, and you’ll be required to bow in front of the figure – with piped music echoing all over the room it’s a truly surreal experience. The Kim Jong-il rooms are less stacked with goodies, and instead feature heavily corporate treats and electronic gadgets. Perhaps most interesting is the basketball donated by former American Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, signed by Michael Jordan, of whom Kim is apparently a big fan; on receiving the ball he was said to have been eager to get outside for a quick jam.

If budgetary constraints or possession of the wrong kind of passport make a trip to North Korea impossible, there are a number of ways to peer into the country from outside.

From South Korea

The two Koreas share a 250km-long border, and though the area around the Demilitarized Zone that separates them is largely off-limits, there are a number of vantage points from which you can look across. DMZ tours from Seoul are highly popular. Itineraries vary, but can include views of the North from an observatory, a trip inside tunnels dug by North Koreans in preparation for an attack on Seoul, as well as the chance to step onto DPRK territory in the Joint Security Area. While these excursions are good value, you can visit a similar observatory and tunnel for free on a guided tour from the remote town of Cheorwon (p.145), and there’s another observatory just north of Sokcho on the east coast (p.151). It has, in the past, been possible to take an expensive tour across the border to the gorgeous mountains of Kumgangsan, but these trips were cancelled with the deterioration of inter-Korean relations in 2008; ask at a tourist office to see if they’ve been resumed.

From China

Two Chinese provinces border North Korea. Over one million ethnic Koreans live in Jilin (a city as well as a province) and another 250,000 in Liaoning – the latter even contains an autonomous Korean prefecture, where the mix of Communism and poverty make some towns fairly similar in feel to the DPRK.

The large city of Dandong is right on the North Korean border, with only the Yalu River (“Amnok” in Korean) separating it from Sinuiju on the other side; those entering North Korea by train will pass through Dandong, and some choose to stop off on their return leg. The two cities offer a rather incredible contrast, with the tall, neon-seared skyscrapers on the Chinese side overlooking poor, low-rise Sinuiju across the water. On Dandong’s riverside promenade you’ll be able to buy (mostly counterfeit) North Korean banknotes and pin-badges, and protruding from this is the Old Yalu bridge, which comes to an abrupt halt in the middle of the river, its North Korean half having been dismantled. From the promenade, you can also take a boat trip to within a single metre of the North Korean shore, and get just as close from Tiger Mountain, 25km east of the city and the easternmost section of China’s Great Wall. Although jumping across for a quick picture may appear tempting, note that one foreign traveller foolish enough to do this spent months in a DPRK gulag after being snatched by hidden guards.

With the mountain and its crater lake straddling the border, it’s also possible to visit Paekdusan (p.353) from the Chinese side, a trip highly popular with South Koreans. The simplest approach is to join a tour from Jilin city; this will include all accommodation, entrance fees and transport, though it’s possible to chalk much of the distance off on an overnight train from Beijing to Baihe, a village close to the mountain.

The highest peak on the Korean peninsula at 2744m, the extinct volcano of PAEKDUSAN ( ) straddles the border between North Korea and China, and is the source of the Tuman and Amnok rivers (Tumen and Yalu in Mandarin) that separate the countries. Within its caldera is a vibrant blue crater lake surrounded by a ring of jagged peaks; it’s a beguiling place steeped in myth and legend. This was said to be the landing point for Dangun, the divine creator of Korea, after his journey from heaven in 2333 BC; more recently, it was also the apparent birthplace of Kim Jong-il, an event said to have been accompanied by flying white horses, rainbows and the emergence of a new star in the sky. Records seem to suggest that he was born in Soviet Siberia, but who needs history when the myth is so expressive. In fact, “new” history is discovered here from time to time in the form of slogans etched into the mountain’s trees, apparently carved during Kim Il-sung’s time here as a resistance fighter, and somehow always in keeping with the political beliefs prevailing at their time of discovery. Emblazoned on one of the slopes surrounding the crater lake is the slogan, “Mount Paekdu, sacred mountain of the revolution”.

) straddles the border between North Korea and China, and is the source of the Tuman and Amnok rivers (Tumen and Yalu in Mandarin) that separate the countries. Within its caldera is a vibrant blue crater lake surrounded by a ring of jagged peaks; it’s a beguiling place steeped in myth and legend. This was said to be the landing point for Dangun, the divine creator of Korea, after his journey from heaven in 2333 BC; more recently, it was also the apparent birthplace of Kim Jong-il, an event said to have been accompanied by flying white horses, rainbows and the emergence of a new star in the sky. Records seem to suggest that he was born in Soviet Siberia, but who needs history when the myth is so expressive. In fact, “new” history is discovered here from time to time in the form of slogans etched into the mountain’s trees, apparently carved during Kim Il-sung’s time here as a resistance fighter, and somehow always in keeping with the political beliefs prevailing at their time of discovery. Emblazoned on one of the slopes surrounding the crater lake is the slogan, “Mount Paekdu, sacred mountain of the revolution”.

Even with so much historical significance, it’s the natural beauty of the place that attracts foreign visitors to Paekdusan. The ring of mountains is cloaked with lush forest, with some pines rising up to over 50m, and bears, wolves, boar and deer inhabiting the area; it’s even home to a small population of Siberian tigers, though you’re highly unlikely to see any. As long as the weather holds – and at this height, it often doesn’t – you may be able to climb to the top of the Korean peninsula by taking a hike to Jong Il peak. A cable car also whisks guests down to the lakeside, where you can have a splash in the inviting waters in warmer months.

With Paekdusan being a place of such importance, every person in the country is expected to make the pilgrimage at some point; the journey is usually paid for in full by the government, even though it’s well over a day by train from Pyongyang. Foreign tourists wishing to visit must take a chartered flight from Pyongyang, and then a car the rest of the way, though due to weather conditions the journey from the capital is usually only possible during warmer months. It’s also possible to visit from the Chinese side, as thousands of South Koreans do each year.