The Coase Theorem

The Coase TheoremPROPERTY SOLVES A GREAT MANY PROBLEMS about the assignment of responsibility over resources and creates incentives for the management of resources that generally assure good custodial practices. Owners of houses have incentives to make sure that the roof does not leak and the plumbing functions properly. Owners of businesses have incentives to assure that shops are clean, safe, and attractive to customers. But the private-property strategy, which entails chopping up the world into small units of resources, each governed by its own owner-manager, also creates problems. The little boxes of owner-sovereignty can create bottlenecks or barriers to access for neighbors, which prevent property from being used to its highest potential. And owner-sovereigns do many things on their property that will have indirect effects on neighbors. Economists call these neighborhood effects “spillovers” or “externalities.” As discussed in Chapter 3, externalities are the effects of actions taken by one property owner that impose involuntary benefits or costs on others. The qualifier “involuntary” is important: If an action by one property owner has the consent of another property owner, then the action should not be considered an externality. Our focus in this chapter is on how the law regulates these neighborhood effects or externalities, which are in a real sense created by the exclusionary strategy of property.

Neighborhood effects can be either positive or negative. Lawn care provides a simple illustration. If I am highly conscientious about tending to my lawn—keeping it neatly cut, free of weeds, and watering it to maintain a nice shade of green—then I enjoy certain benefits, whether it be pleasure at looking at my lawn, pride in seeing the effects of my labors, or an increase in the market value of my home as a result of “curb appeal.” But these efforts also produce positive spillover effects for my neighbors. They too will obtain some pleasure from looking at my lawn, and the market value of their homes may increase (slightly) because they are situated near someone with a fine-looking lawn. These are “free goods” to them that I have provided without any explicit payment for my efforts.

Conversely, if I am not conscientious about tending to my lawn—if I let it go to seed, let the crab grass proliferate, and so forth—then this will produce negative spillover effects for the neighbors. They will incur some displeasure from viewing my unsightly lawn, the market value of homes in the neighborhood may decline (slightly), and there is even some evidence that unkept or poorly maintained property may encourage other types of antisocial behavior in the neighborhood (this is the “broken windows” thesis—that poorly maintained property can cause an increase in criminal activity in a neighborhood1 ). These are also free—but unwanted—“bads” created by my lack of effort.

In this chapter we explore various strategies for regulating impediments to access by neighbors and neighborhood spillovers. We will consider strategies based on tort liability, modification of property rights, contracts running with the land, and public regulation. These strategies are both substitutes and complements to each other. The question in each case is which strategy or combination of strategies makes the most sense. All things being equal, we want to encourage positive externalities and discourage negative externalities. But of course, all things are never equal. Legal mechanisms are costly, both in terms of the costs of the mechanisms themselves—legal fees, for example—and because they restrict the discretion of property owners as to how they manage or use their individual units of property. These restrictions represent opportunity costs, in the sense that property owners may no longer be able to put their property to certain uses that they may value more highly than the uses permitted by the legal mechanism. It is always necessary to weigh the gains from adopting particular legal mechanisms or combination of mechanisms, in terms of more positive and fewer negative externalities, against the costs of these mechanisms. The need to consider these tradeoffs is one of the lessons of the most famous article about neighborhood effects ever written, to which we turn next.

The Coase Theorem

The Coase TheoremThe modern analysis of neighborhood effects or externalities has been strongly influenced by the work of Ronald Coase. Coase wrote a pathbreaking article in 1960 that focused on simple negative spillovers, such as a confectioner whose machinery causes vibrations that disrupt a doctor’s examining room next door, or a rancher whose cattle wander onto a farmer’s land and trample the crops.2 Coase engaged in a thought experiment, in which he asked how these problems would be resolved if it were costless for the neighbors to enter into contracts with each other over the use of their respective properties. The conclusion he reached was that the neighbors would always agree on the use of the land that maximizes the joint value of their respective properties. If the law favors the more productive use, then the neighbors will agree to continue that use, because the owner of the less productive use will not be able to muster a side payment sufficient to induce the more productive user to desist or modify the more productive use. If the law favors the less productive use, then the owner of the land with the more productive use will be able to muster a side payment that will induce the owner of the less productive use to desist or modify that use. If contracting were costless, the neighbors would contract for modifications in their respective activities until they reached the point at which further gains would not induce additional modifications in the use of either property.

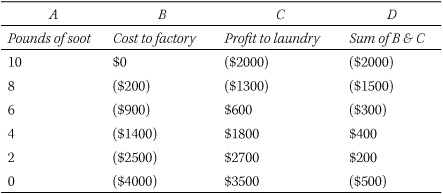

A simple numerical example illustrates the argument. Suppose there are two neighboring landowners, a factory and a laundry. The factory uses a production process that emits soot. The soot penetrates into the laundry, so that the more soot the factory emits, the more difficult it is for the laundry to produce clean clothing. Assume the problem can only be controlled by the factory installing various types of soot arrestors. The more effective the arrestor, the more expensive it is to install and operate. But the more effective the arrestor, the cleaner the clothing produced by the laundry, which increases its sales and its profits. The schedule of costs and profits looks like this:

Under Coase’s thought experiment, it doesn’t matter whether the law says the factory has a right to emit as much soot as it likes, or if it says that the laundry has a right to be free of soot, or if it prescribes some intermediate position. If contracting is costless, the parties will trade away their rights in return for side payments until they reach the outcome that maximizes their joint wellbeing. Obviously, neither of the extreme results—complete freedom to emit soot or complete prohibition on emitting soot—represents a stable solution. If the entitlement goes to the factory, the laundry will be willing to make side payments to the factory if it will install arrestors. At least for the less expensive arrestors, the laundry gains more in profits than it would cost to install arrestors. Conversely, if the entitlement goes to the laundry, the factory will be willing to pay the laundry to let the factory emit some soot. At least for the most expensive arrestors, the costs to the factory exceed the profits lost by the laundry. The proposals will go back and forth, but with zero transaction costs, the bargaining will continue until the parties settle on four pounds of soot. At this level, the joint wealth of the factory and laundry is maximized at $400, and neither party can make an offer to the other that will make both of them better off. For example, if the laundry tries to convince the factory to reduce emissions to two pounds, this will increase the laundry’s profits by $900 ($2700 – $1800) but will cost the factory $1100 (by increasing its cost from $1400 to $2500). No deal. Similarly, if the factory tries to convince the laundry to let it increase emissions to six pounds, this will save the factory $500 (by reducing the cost from $1400 to $900), but the laundry will lose $1200 in profits ($1800–$600). Again, no deal.

What are the lessons to be drawn from this thought experiment? Coase did not believe that contracting is costless. To the contrary, he thought it always consumes significant resources. So, what’s the point?

One point often drawn from Coase—the so-called reciprocity of causation—sits rather uneasily with property law. Coase was at great pains to point out that there would be no use conflict if either party were absent. So when there is a conflict between cattle and crops, confectioners and doctors, or factories and laundries, Coase thought it is incorrect to say that the cattle, the confectioner, or the factory causes harm to the crops, the doctor, or the laundry, respectively. Without the crops, the doctor, or the laundry there would be no conflict. The economic question is which activity is more valuable if we cannot have both, and in a zero-transaction-cost world the opportunity cost will be reflected in the size of the payment that would be offered by the one who lacks the entitlement.

Coase’s agnosticism about causation does not accord with widespread moral intuitions. The owners of damaged noses do not cause punches in the sense that the owners of overactive fists do. And when we get to questions of murder and rape in criminal law, Coasean causal agnosticism is a nonstarter. With respect to property, too, causal agnosticism does not square with the structure of entitlements. When someone owns Blackacre, the exclusion strategy protects the owner against an open-ended set of invasions, ranging from intrusions by persons and large objects to interferences with use from unusual odors and sounds. When the conflict between cattle and crops, or confectioners and doctors, or factories and laundries arises, we are not writing on a blank slate. The owner has a presumptive right against such invasions. In high-transaction-cost settings, we may sometimes have to overcome these transaction costs in the interest of mutual accommodation and maximizing the value of resources—think of airplane overflights. But the basic structure of entitlements is inconsistent with Coasean causal agnosticism in important respects. Whatever the exact source and justification of our moral intuitions against force and theft, the basic structure of property entitlements sounding in exclusion makes the system easy to understand and use, among all the far-flung parties who are expected to respect owners’ rights.3 In other words, there are transaction-cost reasons—as Coase would be the first to appreciate—for not treating causation in resource disputes as symmetric.

Notwithstanding these reservations about the conception of property implicit in Coase’s article, his emphasis on the importance of transaction costs and the possibility of exchange of rights offers valuable lessons for courts and lawyers. One lesson is that if high transaction costs make contracting impossible, then perhaps the law should mimic the result the parties would agree on if they could contract. If we assume that all parties are rational maximizers, that is, that they always want more of whatever it is they value, and if we assume that all values can be expressed in terms of money, then this suggests that the law should try to achieve the result that maximizes the joint wealth of the affected parties measured by their willingness to pay. Obviously, these are debatable assumptions. Irrationality is not uncommon. Many would strenuously insist that all values cannot be cashed out in dollars. And setting the entitlement (to emit or prevent emissions) will have distributive consequences in that having the initial entitlement will make that party better off. But the Coase theorem is widely cited by those who think that efficiency is an important value in the design of legal institutions, and the thought experiment seems to provide intuitive support for the importance of trying to achieve efficient results.

A second lesson is that lawyers should think about possible contractual solutions to externality problems when they are feasible. Litigation and regulation are not the only or even usually the best solutions to problems about access over neighboring property or regulating spillovers. Neighbors can negotiate contracts to modify their property rights by easements or can enter into contracts governing the use of land that run with the land. (Many problems are solved by more informal understandings, including norms of live and let live.) These “Coasean bargains” may provide a better solution than litigation or public regulation.

A third possible lesson is that the law should be designed so as to facilitate contractual solutions to externality problems. Here, two lines of inquiry have emerged in response to Coase. The first and less-developed line of inquiry picks up on his suggestion that the initial delimitation of rights must be clearly established to permit market transactions to transfer and recombine rights. This perhaps suggests that bright line rules will facilitate contractual exchanges of rights.4 But this conclusion, if correct, is in considerable tension with first point above about the desirability of having the law mimic the outcome the parties would reach if transaction costs were zero, which seems to require highly discretionary entitlement rules. It may be that the law can either encourage ex ante bargains or can provide an ex post substitute for bargains, but cannot easily do both.

The second line of inquiry, which has consumed a tremendous amount of intellectual energy, asks whether entitlements should be exchanged only with the consent of the parties or should be allowed to be taken by one party on payment of a judicially determined price. This is the famous distinction introduced by Calabresi and Melamed between “property rules” and “liability rules.”5 An entitlement protected by a property rule must be purchased through a voluntary exchange of rights. An entitlement protected by a liability rule can be taken unilaterally in return for a payment of just compensation, as when the government uses its power of eminent domain to acquire property (see Chapter 9).

Commentators, including Calabresi and Melamed, initially assumed that property rules should prevail in low-transaction-cost settings where Coasean bargains are possible. Coasean bargains assure efficiency; at least the affected parties who agree to the exchange must be better off, or else they would not enter into the agreement. And requiring the consent of all the owners protects subjective values in circumstances where owners place a higher value on their property than the market does. In high-transaction-cost settings, however, it was thought to be preferable to switch to liability rules. Because the party forcing the exchange must pay just compensation, which is usually set at fair market value, the party forcing the exchange will do so only if the new use is more valuable than the present market value. Thus, compelled exchanges (liability rules) were thought to promote efficient solutions in the presence of high transaction costs—in the sense of maximizing market-measured wealth. Of course, compelled exchanges are not necessarily efficient in the broader sense that asks whether the welfare of the parties is enhanced, because such exchanges will sometimes result in a sacrifice in subjective values not captured by markets. For liability rules to begin to reflect subjective values, they need to be more complicated than simply a judicial estimate based on market prices, but perhaps because such schemes would add to administrative costs we rarely see them in practice.

The Calabresi and Melamed analysis, building on Coase, tends to view the problem of externalities ex post, after a particular problem of access or a spillover has developed. From this perspective, high transaction costs can appear to be ubiquitous. Even if there are only two parties, once they are locked in a dispute they stand in a bilateral monopoly relationship that may lead to bargaining breakdown. The ex post perspective therefore tends toward the conclusion that liability rules are always superior to property rules on efficiency grounds.

More recently, scholars have shifted from the ex post to the ex ante perspective, asking what incentives these different modes of protection create for future behavior. Here, the case tends to shift back toward property rules, or, according to some, more elaborately tailored liability rules designed to tweak incentives. Because property rules protect subjective values that are not reflected in the market’s valuation of property, they protect reliance interests and encourage investment. Property rules are also relatively simple for duty-holders to interpret (keep off, or else) and for courts to administer. And property rule protection creates an incentive for owners to generate new information about the uses to which their property can be put.6 So from a dynamic or ex ante perspective, it would seem that property rule protection should remain the norm, and liability rules the exception.

Tort Liability: Nuisance

Tort Liability: NuisanceOne way the law seeks to control externalities is through tort liability. The tort of trespass to land plays a role here, insofar as some access issues or negative externalities may give rise to an action for trespass. For example, if A engages in blasting that causes rocks to block B’s driveway, or if A engages in slant drilling to extract oil from underneath B’s land, these activities would give rise to a claim for trespass. By far the most important form of tort liability for regulating neighborhood effects or externalities, however, is nuisance.

Two different types of legal action bear the name “nuisance”: public nuisance and private nuisance. The Restatement of the Law Second, Torts classifies both as a type of tort. It is not clear that this is correct. Torts are typically interferences with some private right, such as bodily integrity, reputation, or property. A public nuisance is defined as an unreasonable interference with a right common to the public as a whole. A public nuisance is thus perhaps more accurately regarded as a public action, akin to a criminal prosecution or an action to enforce the public trust doctrine (discussed in Chapter 3), rather than a tort.

The classic example of a public nuisance is blocking a public highway or a navigable waterway. Public nuisance actions are usually brought by public authorities, such as the state attorney general or the county prosecutor. The relief sought is usually an order of abatement—in effect, an injunction requiring the defendant to cease interfering with the public right. Sometimes, however, private parties are allowed to bring public nuisance actions, if they can show that they have suffered “special injury” from the interference with the public right. An example would be a landowner who has been barred from reaching his or her home by the blockage of a public highway. Here, the landowner is allowed to act as a “private attorney general,” seeking to vindicate the public right, which will also redress the special injury suffered by the landowner.

Private nuisance clearly is a form of tort liability. A private nuisance is defined as an unreasonable interference with a private right: the use and enjoyment of land. Nuisance differs from trespass in that nuisance protects use and enjoyment rather than possession. Thus, trespass applies when there has been an intrusion by an object large enough to interfere with some portion of a person’s right to possession of land. An intrusion by another person, a vehicle, a building, an animal, or a body of standing water would be examples. Nuisance applies to any thing that affects the use and enjoyment of land. Thus, intrusions of the sort covered by trespass can be claimed as a nuisance insofar as they too impair the use and enjoyment of land. (The actions are not mutually exclusive with respect to these intrusions, although some definitions of nuisance exclude anything that could be a trespass.) In addition, however, nuisance covers all sorts of others kinds of intrusions that cannot be said to displace a person from possession of land but nevertheless can be annoying or debilitating: smoke, odors, vibrations, sound waves, pollution of streams, radiation, beams of light—all these things are potentially subject to liability as nuisances.

An intentional trespass—one that the defendant knew or should have known would occur—is governed by a standard of strict liability. Liability attaches whether or not the intruder exercised reasonable care. And liability attaches whether or not the intrusion caused harm. Thus, a person who can establish an intentional trespass by the defendant is always entitled to an award of nominal damages, even if the plaintiff cannot prove actual damages. And if there is a likelihood that the intrusion will continue or will be repeated in the future, the court may enjoin the trespass, even if actual harm cannot be shown.

In sharp contrast to trespass, the standard of care for determining when an intrusion will give rise to nuisance liability is difficult to define or pin down. An intentional nuisance—an intrusion that the defendant knew or should have known would interfere with the plaintiff’s use and enjoyment—is subject to liability only if the intrusion causes “substantial” harm and is “unreasonable.” Exactly what these terms mean, and how they will be applied in any particular circumstance, is difficult to say. About the only safe generalization is that nuisance liability is very context-dependent and is determined in a case-by-case fashion.

The requirement of substantial harm is generally understood to eliminate liability for what English courts called “trifling inconveniences.” Smoke from your neighbors’ backyard barbecue and the yelps from their dog may irritate you, but a court is not likely to find that these sorts of intrusions reach the “substantial harm” threshold. Context is clearly relevant here. Erecting a huge neon sign does not impose substantial harm in Times Square, but it very likely might in a residential neighborhood.

In addition to imposing substantial harm, the intrusion must be unreasonable. What this means is even more elusive. The Restatement of the Law Second, Torts says that unreasonableness is determined by a balancing test: One asks whether the “the gravity of the harm outweighs the utility of the actor’s conduct.”7 This suggests a kind of back-of-the-envelope cost-benefit analysis. Courts do not seem very comfortable with this suggestion, however. At least it is hard to find many decisions that engage in an explicit balancing of harms and benefits in determining whether particular intrusions are reasonable or unreasonable.

Several other factors seem to play a role in guiding courts in nuisance cases. Invasiveness is one. The Restatement’s cost-benefit definition of unreasonableness suggests that anything done on neighboring property that will affect the use and enjoyment of the plaintiff’s property can give rise to a nuisance claim. But courts seem uncomfortable with claims that aesthetic blight by itself can constitute a nuisance. Garish paint jobs, junked cars, or poorly kept lawns will usually escape liability. Courts are much more likely to find a nuisance when the defendant is responsible for some invasion of the plaintiff’s column of space, as by air pollution, water pollution, or loud noise. In this sense, nuisance seems to reflect the structure of trespass, where a physical invasion is required.8 But there are exceptions to this generalization. Funeral homes and halfway houses for paroled prisoners and recovering drug addicts are often challenged as nuisances, with some success. And if the defendant does something on the defendant’s land for the specific purpose of irritating a neighbor, such as erecting a “spite fence,” there is a high probability that courts will find this to be a nuisance, at least if the action has no obvious utilitarian purpose other than imposing harm.

The nature of the locality is another important contextual factor. As the Supreme Court once stated, “A nuisance may be merely a right thing in the wrong place, like a pig in the parlor instead of the barnyard.”9 Thus, a smoky factory is less likely to be found to be an unreasonable use of land in a district comprised of smoky factories, than it would be in a residential neighborhood. Nuisance law in this regard functions like zoning, encouraging different uses of property to be clustered together in different neighborhoods, where spillover effects are less likely to impose substantial harm on neighbors.

Temporal priority is yet another factor, although somewhat weaker than invasiveness or the nature of the locality. Courts naturally look more skeptically on a defendant who seeks to introduce a new and unsettling use into an established neighborhood, than they do when long-established uses are challenged by those who want to upgrade the area. Nevertheless, “coming to the nuisance” is usually rejected as an affirmative defense. Temporal priority is a factor to consider in the balance, but is not decisive, especially because, as we saw in Chapter 2, encouraging a race to be the first is quite undesirable in some contexts. A strong coming to the nuisance defense would encourage people to use their parcels as intensively and as early as possible, in order to establish the right to engage in such activities in the face of a new more sensitive use. The result would be like a prescriptive easement (see below) without the necessity of meeting the requirements for acquiring rights by prescription. Likewise under a strong version of coming to the nuisance, someone with a sensitive use in mind would also want to engage in it earlier than may be optimal, in order not to lose to someone else with an inconsistent use.

The question of remedy, and in particular the debate over the propriety of property rules versus liability rules, also looms large in nuisance cases. The discussion here is often framed in terms of the New York Court of Appeals decision in Boomer v. Atlantic Cement Co.10 In Boomer, a cement plant located near Albany emitted dirt, smoke, and vibrations, and the trial court found this conduct was a nuisance to a group of neighboring property owners. The sole question on appeal was whether the court should issue an injunction against the nuisance, or should instead order some other relief, such as temporary or permanent damages. Enjoining the nuisance would in effect recognize a property rule: The cement plant would then have to purchase the consent of the neighbors to continue operating. An award of permanent damages would protect the neighbors with a liability rule: The cement plant could acquire their rights in a compelled exchange in return for the payment of damages.

The court acknowledged that prior New York decisions indicated an almost automatic presumption in favor of injunctive relief to protect the subjective values associated with property ownership. But it decided that an injunction should be denied, provided the cement company agreed to pay permanent damages to the property owners. The court was clearly concerned that an injunction might result in shutting down the plant, which cost $45 million to build and employed more than 300 people. It regarded this as an unacceptable cost to the community. The dissent pointed out that this was the functional equivalent of giving the cement company a private right of eminent domain to condemn a permanent easement to commit a nuisance.

The analysis in Boomer is entirely ex post. The court took the decision to build the cement plant in a neighborhood with many residents as a given, and balanced the benefits to the plaintiffs of being free of the nuisance against the investment and jobs that might be lost if the nuisance were abated. Adopting a liability rule, which allowed the cement company to coerce an exchange of entitlements, seems correct from this perspective. If we view the problem from an ex ante perspective, however, it is much less clear that this is right. Perhaps we want cement plants to take greater care in determining where they locate, assuring that they leave enough space between the plant and neighboring property owners to minimize negative spillover effects. Adopting a property rule, that is, awarding an injunction against the nuisance, would have provided a powerful incentive for cement plants in the future to acquire the necessary rights to prevent such problems from arising. Alternatively, the dire ex post situation could be avoided and the residents given more protection, if the cement company had to justify its choice of prospective location for the plant in a proceeding at which the residents had notice and an opportunity to be heard. Such requirements are commonly built into environmental statutes and requests for variances or special exceptions to zoning regulations (considered below). They are also a feature of statutes providing for private eminent domain for easements of road access and to water.In a sense, what is at stake between the cement plant and the residents is an easement allowing the plant to create a nuisance, another land use device to which we will soon turn.

The Boomer situation is prime grist for analysis of property rules versus liability rules, and there is another sense in which the Calabresi and Melamed perspective is ex post: its view of the nature of entitlements. To Calabresi and Melamed, a collective decision over who gets the entitlement—polluter or resident—intersects with the question of how it is protected—property rule or liability rule. This gives four logical possibilities. Under Rule 1, the resident has the entitlement to be free from pollution, and the polluter must bargain in a consensual transaction with the resident or residents who hold this entitlement. Under Rule 2, the resident still has the entitlement, but the remedy is an award of damages. So if the polluter causes $100 of damage a day, the resident can sue multiple times to collect $100 a day or once to collect the discounted stream of daily $100 payments from now on, called “permanent damages.” But under Rule 2, the resident cannot stop the pollution: The polluter can keep on polluting as long as the officially determined damages are paid. In effect, the polluter can take an easement for the “price” of the permanent damages. When there are many residents, any one of whom might hold out, there is a tendency, as in Boomer itself, to consider Rule 2 protection.

As for Rules 3 and 4, Calabresi and Melamed apply a twist on the Coasean notion that causation is reciprocal: If the harmful interaction is caused either by the polluter or the resident, either one in principle could have “the entitlement” to prevail in the situation of conflict. So under Rule 3, the polluter has the entitlement to pollute, protected by a property rule, in the sense that the resident is going to have to bribe the polluter to stop if that is to be the result. Finally, under Rule 4 the polluter has the entitlement to pollute, but the resident can take this entitlement—and shut the pollution down—upon payment of officially determined damages. Strikingly, at around the same time as Calabresi and Melamed’s article came out, in Spur Industries, Inc. v. Del E. Webb Development Co., the Arizona Supreme Court, facing a case in which a retirement community had expanded close to a cattle feedlot, allowed the developer to obtain an injunction upon payment of the damages to the feedlot for the costs of shutting down.11

Spur is virtually the only nuisance case in which this “Rule 4” approach has been adopted. Why? For one thing, from the point of view of property, the symmetry between Rules 1 and 2 on the one hand and Rules 3 and 4 on the other, is illusory.12 Consider Rule 3. When does a polluter have the “right” to pollute? This is controversial enough in the first place, but a closer look reveals that the common law provides for rights to pollute in only very narrow circumstances. One can have an easement to pollute either by grant or prescription—we will return to easements in the next section. But the common law emphatically does not include a right to pollute in the basic package of rights associated with fee simple ownership. Owning Blackacre gives the right to be free from a wide range of intrusions—not all spelled out in advance—but not the right to commit invasions. In the Rule 3 scenario as envisioned by theorists like Calabresi and Melamed, the polluter, on closer inspection, may not have such a right at all. Imagine the resident erecting a giant fan to blow the pollution back onto the factory grounds. If the polluter cannot get an injunction against the fan, this suggests that the polluter may have been able to get away with pollution but did not have the right to commit it. This understanding is very important when the polluter becomes subject to environmental regulation: Such regulation is not regarded as a taking of any preexisting right. More generally, the need for a simple, lumpy package of rights against sundry invasions breaks the symmetry. We are not writing on the Coasean blank slate assumed by the Calabresi and Melamed framework. Although we sometimes move from injunctions to damages in the law of nuisance (Rule 1 to Rule 2) as in Boomer, there is no “right to pollute” that is symmetric to the right to be free of pollution, and hence there is no need to soften the “right to pollute” (Rule 3) with a liability rule that allows such a “right” to be taken in a coerced exchange (Rule 4). Small wonder then that examples of Rule 4 are so hard to come by.

Modification of Property Rights: Easements

Modification of Property Rights: EasementsA second, and very different, strategy for handling certain kinds of neighborhood effects or externality problems relies on a modification of property rights known as an easement. Easements carve out particular uses of property and transfer control over those uses to someone other than the owner of the property from which the carve-out occurs. Easements are very commonly used to overcome impediments to access to land that can limit development and use and enjoyment of land. Familiar examples are right-of-way easements and utility easements. But easements are also used to control particular uses of land. For example, conservation easements, which are becoming increasingly popular, prohibit certain kinds of development of land in order to enhance ecological resources, which provide positive externalities for other landowners in the neighborhood and society more generally.

Let us start with some vocabulary. The property from which the easement is carved out is called the servient estate. The property whose owner has the right to engage in or prohibit the use that is singled out is called the dominant estate. If the easement permits the owner of the dominant estate to perform some act on the servient property, it is called an affirmative easement. If the easement requires the servient property owner to desist from engaging in certain activities or uses on the servient property, it is called a negative easement. Most easements are appurtenant to the ownership of land, meaning that the benefit of the easement is attached to a particular parcel of land, and runs with the ownership of the benefitted land (the dominant estate). Some easements, at least in the United States, are held in gross, meaning that the benefit of the easement is not linked to ownership of any particular land, but rather is owned by some person or entity without regard to whether they own any particular land or dominant estate.

Some illustrations may help clarify these distinctions. Suppose A and B own adjacent parcels of land. A grants B the right to drive motor vehicles across A’s land to reach a public road. A owns the servient estate, and B owns the dominant estate. B has an affirmative easement in A’s land; the easement is appurtenant to the ownership of B’s land, meaning that whoever owns B’s land in the future will also own the easement allowing access by motor vehicles to the road. Now, suppose C decides to grant a conservation easement to the D foundation, in which C promises not to fill, drain, develop, or otherwise disturb fifty acres of wetlands on C’s land. C’s is the servient estate, and D is the dominant property owner. D has a negative easement in C’s land; the easement is in gross because it is not attached to any particular land owned by the D foundation.

An easement is generally regarded as a property right, and hence it is proper to speak of easements as a strategy for managing externalities through modifications of property rights. It is instructive in this regard to contrast easements with licenses. As discussed in Chapter 4, a license, in its simplest form, is a waiver of the right to exclude. Suppose A says to B: “Go ahead and drive your car across my land to reach the road.” This means A cannot use self-help or legal means to stop B when B, in response to this statement, starts to cross A’s land. But the permission is understood to be revocable, in the sense that A can change A’s mind tomorrow and deny further permission to cross. It is also understood to create no rights good against third parties. Thus, if B starts to cross and finds the way blocked by C, B has no legal claim against C.

A and B could also sign a contract that says A will allow B to cross A’s land for one year, provided B pays A $10 for each crossing. This would be enforceable as a bilateral contract between A and B, and B would have an action for breach of contract if A decided after six months to refuse further crossings by B. But it would still be regarded as a contract right. The right is personal to A and B and would not necessarily run to any successor to ownership of B’s land. And the right would not necessarily create any rights against third parties.

An easement is a more robust right than either a license or a contract. An easement is typically irrevocable, either for a designated period of time or in perpetuity. Although one can purchase easements, they are often granted gratuitously or as part of a more general exchange of property rights; periodic payments are rarely required. Easements do not depend on the personal identity of the grantor and grantee. Easements attach to ownership of land and follow the ownership of land into whoever’s hands it may fall. This is always true of the servient estate. It is also true of the dominant estate, at least with respect to appurtenant easements (which are more common). Finally, although authority for this is relatively thin, easements appear to be regarded as rights in rem, in the sense that all the world is subject to a duty not to interfere with an easement. Given the relative permanence, impersonality, and in rem effects of easements, it is not surprising that they have been regarded as property rights.

How does one create an easement? There is the right way, and there are a bunch of legal doctrines that bail out people who have failed to create an easement the right way. The right way to create an easement is by a written grant. This is a writing that includes all the elements required to make a valid transfer of real property by deed from one person to another (see Chapter 7). The writing should include the identity of the servient and dominant lands (or of the benefitted owner in the case of an easement in gross), a description of the easement, and whatever formalities are required by state law for a valid transfer of land, such as attestation of signatures. To assure that the easement is not wiped out by a future good-faith purchaser without notice (see Chapter 7), it should be recorded. To ensure that the easement appears in the chain of title of the properties that are benefitted and burdened, it should not be created by reservation in a grant to some other party. In other words, if A wants to convey an easement to B, A should not try to create the easement by reservation in a deed to C, since the attempted grant to B will not appear in B’s chain of title. 13

With distressing frequency, parties neglect to create an easement the right way, that is, by written grant. Instead, they behave as if the dominant estate has certain use rights with respect to the servient estate, and then something happens, such as a transfer of one of the properties to a stranger, which causes the owner of the servient estate to deny the existence of any use rights in the dominant estate. Litigation then ensues. The courts could respond to this common situation by saying “tough luck,” and denying dominant claimants any rights absent a written grant. But, perhaps not surprisingly, courts have generally taken an ex post view of the problem. Once there has been a falling out, the parties are in a bilateral monopoly situation, and negotiation of a written grant may be out of the question. Courts have accordingly created a number of doctrines that allow easements to be created as matter of law.

Two of these doctrines are based on implied intent. Where there is some sort of preexisting use, such as a driveway or a utility line, and the owner subdivides the property, courts will sometimes declare that an easement by implication exists. The required elements are said to include (1) severance of title to land held by one owner; (2) an existing use, which was visible and continuous at the time of the severance; and (3) reasonable necessity for continuation of the use after severance. The doctrine apparently rests on the assumption that the parties must have intended an easement permitting continuation of the use but neglected to reflect this intent in a written instrument.

Even absent a preexisting use, if an owner subdivides property in such a way as to leave it landlocked, courts will sometimes declare an easement by necessity. The required elements are said to be (1) severance of title to land held by one owner and (2) strict necessity at the time of the severance. Again, the rationale is said to be that the parties would not want to create a subdivision in which one or more parcels were landlocked, because this would severely impair the value of the property. Some states take the idea of an easement by necessity in a different direction, allowing a landowner with insufficient access to petition a court or other official to allow it to condemn an easement and pay damages. This use of what Calabresi and Melamed would call a liability rule promotes access but can be quite threatening to the target of the condemnation. These statutes typically allow the condemnee to object on the grounds that the easement is not necessary for access, for example, because alternative means of access exist.

A third way to create an easement as a matter of law is by prescription. This is the analogue of adverse possession, considered in Chapter 2, with the twist that here the running of the statute of limitations creates an adverse right of use rather than possession. The difference turns on the behavior of the adverse user. If the adverse user acts like an owner, exercising a general right to exclude others and manage and control the property, then adverse possession governs. If the adverse user merely engages in a particular use of the property—such as crossing it or using it as a ditch to drain water — then prescription governs. Otherwise, the same elements that apply in determining whether someone has established title by adverse possession also apply in ascertaining whether an easement by prescription exists: The use must be open, notorious, continuous, exclusive, and under a claim of right for the period of the statute of limitations. With adverse use, as opposed to adverse possession, the continuous and exclusive elements apply somewhat differently. The touchstone in resolving these elements is what a normal holder of an easement would do. This feature is nicely captured in old English cases, which justified prescription on the fiction that the servient owner had long ago granted an easement to the dominant owner, but the grant had been lost.

The fourth and final way to create an easement as a mater of law is by the doctrine of equitable estoppel. This doctrine is grounded in general principles of equity. The required elements are (1) the giving of an express license to use property, (2) the reasonable expenditure of significant money or labor by the licensee in reliance on this license, and (3) circumstances indicating that revocation of the license would be unjust. Technically, equitable estoppel does not create a property right. It merely reflects the judgment of a court that it would be inequitable for the owner to revoke the license; hence the court enjoins the servient owner from revoking the license. Given that the theory does not technically create a property right, questions may arise about how long an easement by estoppel lasts, and whether it is transferable and descendable.

The four devices for creating an easement as a matter of law only work for affirmative easements. Some actual use on the servient land is required. This is in significant part a matter of notice. If there is some actual physical activity on A’s land, then A can be expected to be aware of this fact. In contrast, if the claim is that A should be required to desist from engaging in some use, perhaps because this is what A or A’s predecessor did in the past, it is not obvious that A would have ever thought about the possibility of a legal claim for an easement being advanced based on A’s having done nothing. The problem of notice is so severe that English courts refused to recognize any negative easements outside four narrow categories. 14 U.S. courts are more tolerant — at least when the negative easement is created by grant. But U.S. courts have refused to allow negative easements to be created by prescription, 15 and as a practical matter do not allow negative easements to be created by implication, necessity, or estoppel either. A few U.S. courts have created what amounts to a negative easement by prescription in ruling that constructing a building that casts a shadow on a neighbor’s solar collector can be a nuisance.16 But in addition to the problem of notice discussed above, this creates an enormous incentive to be first to capture the sun’s rays, either by putting up a building or a solar collector, and thus could give rise to wasteful racing behavior, analogous to what we see with the rule of first possession (see Chapter 2). In some states, solar access is now governed by statute, usually through a system of permitting or prior appropriation along the lines of water law (see Chapter 3). 17

The multiple ways of creating an easement are mirrored by multiple ways of terminating easements. The orthodox method, again, is by grant. The parties can execute a written instrument that terminates the easement, following the formalities of a real estate deed. Easements can also be terminated by abandonment, if the servient owner can show that the dominant owner has failed to use the easement for some time or has made statements indicating an intention no longer to use it, and has taken some affirmative act reflecting the intent to abandon. Distinct, but somewhat similar, is termination by prescription. If the servient owner blocks the easement, for example, by putting up a fence across a right of way, and the dominant owner fails to take action to reopen the easement before the statute of limitations runs, the servient owner may be able to claim termination by prescription. Finally, an easement will be terminated by merger, if the dominant and servient tracts come under ownership by the same person. No one can have an easement over one’s own land.

How can a servient owner ensure that the dominant owner does not overuse or misuse an easement? The law here reflects a mix of bright line rules and rules of reason, analogous to the trespassnuisance divide. If the dominant owner acquires additional land and attempts to use an existing easement to reach the new land, this will always be condemned as a misuse of the easement, even if the increased burden is trivial.18 On the other hand, if the dominant owner’s business grows, with the result that the volume of traffic using an existing easement increases significantly, this will be permitted as long as the increased traffic does not impose an unreasonable burden on the servient owner. Some commentators have expressed frustration with the formality of the distinction. 19 Perhaps the difference in treatment simply turns on the specificity of the underlying rights. Easements are usually clear about the identity of the dominant parcel; thus, in the case of newly added land, there is an unambiguous violation of a clear limitation on the right. Easements are much less likely to be clear about the permitted intensity of use. There is, if you will, a gap in the specification of rights in this case, which must be filled in by the court for the parties, making a standard of reasonableness appropriate. The parties are always free to specify in the easement what volume of use is permitted, and a violation of such a limitation would similarly be subject to automatic condemnation by a court.

Contract: Covenants Running with the Land

Contract: Covenants Running with the LandClosely related to easements are covenants running with the land. Sometimes covenants and easements are lumped together as “servitudes.” We have described easements as modifications of property rights. Covenants could be described the same way. But covenants have a stronger contractual flavor than easements. Covenants always originate in written promises between a grantor and grantee of interests in land. There are no doctrines that provide for covenants as a matter of law, as there are with respect to easements. Covenants typically apply to questions about permissible uses of property, whereas easements more typically involve questions of access. And covenants are much more likely to impose negative rather than affirmative obligations, whereas the obligations of an easement are nearly always affirmative. Indeed, one could say that covenants are simply contracts about the permissible uses of land with one feature not otherwise found in contracts: Covenants “run with the land,” meaning that the benefits and burdens of the promises roll over automatically when the interests of the original promisor and promisee are transferred.

Suppose a developer subdivides a tract of land. The developer requires that every purchaser of a lot in the subdivision take a deed that includes a promise that the purchaser will use the property as a single-family residence only. There is no doubt that such a deed restriction is enforceable as a contract between the developer and the purchaser. Thus, if a purchaser who has signed such a deed attempts sometime later to turn the single-family house on the lot into a duplex, the developer can sue the purchaser for breach of contract. Unless the purchaser can establish one of the standard defenses to such an action (e.g., lack of contractual capacity), the developer should win, and the court would either award damages or enter an injunction to prevent the breach.

Whether or not such a contractual promise is a covenant running with the land comes into play only if the original promisee (the developer) or the original promisor (the purchaser) has transferred the property to someone else. The law has developed two tests for determining whether such promises run with the land: equitable servitudes and real covenants. It is important to stress that equitable servitudes and real covenants do not refer to two different interests in property, like a fee simple and a life estate. They are the same thing. These are simply two different legal tests for establishing whether a contractual promise respecting the use of land runs to successors in interest, as opposed to being merely a personal obligation between the original promisor and promisee. To state the matter differently, we start with the same thing, which is a promise between A and B. The question then becomes, is the promise binding on A1 and/or B1, their successors in interest? To determine the answer to this question, we apply one of two legal tests, the equitable servitude test and the real covenant test. If the promise passes either one of these tests, it is enforceable against the successors. If it does not pass either test, it is only a personal promise between A and B and is not binding on their successors.

Which test do we apply? The equitable servitude test originated with the court of equity in England (Chancery). Hence, if one is seeking an equitable remedy for violation of a promise respecting the use of land by a successor in interest, such as an injunction, one would ordinarily apply the equitable servitude test. The real covenant test originated with American courts that held that certain grantor-grantee promises respecting the use of land run to successors in interest in an action at law. Hence, if one is seeking to recover damages for a breach of a promise respecting the use of land by a successor in interest, one would ordinarily apply the real covenant test. Because, in most jurisdictions, the courts of law and courts of equity merged long ago, and the old forms of action are no longer supposed to limit the authority of courts of general jurisdiction, this differentiation based on whether one is proceeding “at law” or “in equity” seems artificial and outmoded. Perhaps one day it will break down. But for now, the safest assumption is that the type of relief being sought by the plaintiff (injunction or damages) will dictate which legal test will be used to determine if the promise “runs.”

The equitable servitude test was invented by the English Chancery in the famous case of Tulk v. Moxhay.20 Tulk owned Leicester Square and several houses surrounding the square in London. Tulk sold the square to one Elms, by a deed in which Elms promised for himself, his heirs, and assigns, to keep the square in good condition and to allow the residents in the houses surrounding the square to use it as a “garden and pleasure ground.” Ownership of the square passed by several conveyances into the hands of Moxhay, whose deed said nothing about this promise, although Moxhay admitted he was aware of Elms’s original promise because he had seen it in the deed from Tulk to Elms. When Moxhay threatened to build on the square, Tulk sued for an injunction, and won.

The court in Tulk acknowledged that such a promise would not run to a successor in interest in an action at law. In England, covenants run with the land only when they are contained in leases between a landlord and tenant. But the court said this did not preclude a court of equity from issuing an injunction when the successor took with actual notice of the promise. According to the court, because the original promise by Elms no doubt affected the price he paid, “nothing could be more inequitable than that the original purchaser should be able to sell the property the next day for a greater price, in consideration of the assignee being allowed to escape from the liability which he had himself undertaken.” 21 (Is this true? What if Elms assumed the promise was good only until he sold the property to someone else?) The key was that Moxhay had acquired the property with actual notice of the promise: “[I]f an equity is attached to the property by the owner, no one purchasing it with notice of that equity can stand in a different situation from the party from whom he purchased.” 22

Based on Tulk and following decisions, the equitable servitude test has come to be understood to have three elements. (1) The parties must intend that the promise will be binding on their successors. This was satisfied in Tulk because Elms had promised on behalf of himself and his “heirs and assigns.” (2) The successor must have notice of the promise to be bound by the burden of the promise. In Tulk the successor (Moxhay) had actual notice; later decisions established that constructive notice through the recordation of the original deed will also suffice. (3) The promise must be one that “touches and concerns the land.” More on this mysterious phrase in a moment.

Meanwhile, American courts ventured forth beyond what English courts had allowed in enforcing promises against successors in interest in actions at law. English courts allowed covenants respecting the use of land to run to successors only if the original covenant was between a landlord and tenant. If the landlord sold the reversion, or if the tenant assigned the lease, the covenants in the original lease would bind their successors if certain conditions were met (see Chapter 6). American courts took this doctrine and extended it to the context of real estate developments. If the original promise was contained in a deed between a real estate developer and a purchaser of property in that development, the original promise would also run, provided the same conditions developed in the landlord-tenant context were met. The courts described the general condition between the original promisor and promisee that would permit this doctrine to apply as “privity of estate.”

In its full-blown form, the real covenant test has come to be understood to have the following elements. (1) The parties must intend that the promise will be binding on successors. Usually this will be established by language indicating that the parties are promising on behalf of their “heirs, successors, and assigns” or words to that effect. Intention can also be established, however, by a more general consideration of context. (2) The original promise must have been made between grantor and grantee, landlord and tenant, or others who are in “privity of estate.” This type of privity is often called “horizontal,” and it is rarely of much importance in American cases, as nearly all the cases involve promises imposed by real estate developers on original grantees in a new development (grantor-grantee relationship). (3) For the burden of a promise to run, the successor must have acquired the entire interest of the original promisor, in what is known as “full vertical privity.” For the benefit of a promise to run, the successor must have acquired at least part of the interest of the original promise, in what is known as “partial vertical privity.” (4) The promise must be one that “touches and concerns the land.”

As this brief summary suggests, the main differences between the equitable servitude test and the real covenant test are as follows. The equitable servitude test requires that a successor in interest must have notice of the promise, real or constructive; the real covenant test does not. The real covenant test requires privity of estate between the original promisor and promisee and full or partial privity of estate between the successors and the original parties to the promises; the equitable servitude test does not. Both tests require that the original parties intend the promise to bind successors, and that the promise touch and concern the land.

What does the mysterious phrase “touch and concern” mean? The purpose of this requirement is relatively clear. It is designed to differentiate between promises that it makes sense to impose on successors in interest and promises that it makes sense to limit to the original promisor and promisee only. Suppose the original parties include in the deed a promise that the purchaser, a barber, will cut the hair of the seller, a real estate developer, once a month. If the barber subsequently transfers the property to a law professor, obviously it makes no sense to hold that the promise runs with the land. The developer (or the developer’s successor in interest) would not want a haircut by a law professor. Conversely, if the original parties include in the deed a promise that the property will be used for a single-family residence only, this will certainly have an impact on future successors, both of the promisor and the promisee. This kind of promise is clearly one that it makes sense to impose on successors in interest.

Why not simply rely on the parties to the original promise to signal whether they intend the promise to run? The problem seems to be that parties generally fail to attend to this issue on a carefully considered, promise-by-promise basis. The tendency, all too often, is to make lots of promises, and say they all are intended to run. Courts have generally been skeptical that this should be taken literally. The Restatement of the Law Third, Property would reverse this skeptical attitude, and substitute what amounts to a presumption that promises will run, unless they violate public policy. 23 But so far, courts have been reluctant to abandon the touch-and-concern screen for when promises run.

Although unwilling to give up on touch and concern, courts have been stymied about how to specify exactly what this means. Perhaps some progress could be made by reverting to the general reason for having a legal mechanism like servitudes that run with the land: the need for a governance regime to regulate positive and negative neighborhood effects or externalities. Promises that regulate externalities, either by encouraging positive externalities (taking care of the lawn) or discouraging negative externalities (no boarding houses), would be deemed to touch and concern the land. Promises that have no discernible neighborhood effects (cutting the developer’s hair, agreeing to finance a loan from a company affiliated with the developer), would be deemed not to touch and concern the land. To be sure, whether or not something is an externality is often debatable. So asking courts to decide whether a promise regulates externalities would not resolve all the borderline cases, such as whether a promise to buy water from a common well runs with the land.24 But it might at least point courts in the right direction.

Because servitudes running with the land often involve fairly specific promises about land uses, these promises run a significant risk of becoming obsolete. A classic example is a promise to limit all lots in a subdivision to single-family homes: Years later, the area changes such that the highest and best use of all or part of the land is for commercial use such as retail. In the face of such changed circumstances, it may be very difficult or impossible to amend the promises, because all persons owning property in the development would have to agree to the change. Unanimous consent will be very hard to achieve, given that one or more owners may hold out. Perhaps the holdouts could be induced to relent by side payments from the owners who desire change, in a “Coasean bargain.” But freerider problems may prevent the owners who desire change from raising enough funds to induce the holdouts to relent, and after all, the main point of the Coase theorem is that in the real world, transaction costs will sometimes block wealth-increasing deals.

A well-designed package of servitudes will anticipate this problem. It may include specific time limits on different promises, or the entire package may expire after a certain period of time, such as forty years. More recently, well-advised developers have incorporated into packages of servitudes some mechanism for amending the original promises by something less than unanimous consent. Modern condominium developments, for example, make extensive use of servitudes that restrict the use of individual units and the common facilities in a variety of ways (see Chapter 6). But they also typically include some mechanism, such as a supermajority vote of the homeowners’ association, which allows abrogation or amendment of the original promises. Because a supermajority is hard to muster, this allows purchasers to rely on the original package of promises. It also allows for change when a strong consensus develops that change is appropriate.

Absent such an amendment procedure, the primary safety valve for overcoming problems created by changed circumstances is judicial abrogation under what is called (appropriately enough) the changed circumstances doctrine. Courts generally apply a very demanding standard in determining whether to refuse enforcement of covenants running with the land because of changed circumstances. They require evidence that the restriction will be of “no benefit” to property owners who desire to keep it in place. 25 Obviously, if one or more owners object to abrogation, they will usually be able to make some argument that the restriction provides a benefit to them. Other grounds for seeking abrogation include abandonment, laches, and violation of public policy. The difficulty of obtaining judicial modification or abrogation underscores the desirability of including an amendment mechanism in the original package of covenants.

Public Regulation: Zoning

Public Regulation: ZoningThe legal mechanisms for regulating neighborhood effects or spillovers previously considered — nuisance suits, modifications of property rights by easements, and covenants running with the land — are all subject to severe limitations. Nuisance suits are expensive and unpredictable, easements require difficult negotiations or legal action, and covenants running with the land, as a practical matter, can only be imposed by developers in new subdivisions. In light of these limitations, it is not surprising that the law has turned to public regulation as a way of encouraging positive and discouraging negative externalities. A wide variety of laws are designed to regulate land use externalities. Environmental laws limiting air and water pollution, regulating and remediating hazardous waste disposal, and assuring the quality of water supplies are examples. Laws like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), 26 and its many state analogues, seek to control the impacts of new government projects by requiring a careful consideration of effects and alternatives in an environmental impact statement before the project is undertaken.

By far the most common form of public regulation designed to regulate neighborhood effects and externalities, however, are local zoning laws. Zoning laws are of two broad types: Euclidean zoning and planned unit developments.

Euclidean zoning (so named for the Supreme Court case that upheld the constitutionality of local zoning ordinances27 ) starts with a map of the local community. On the map, neighborhoods are marked off in zones having different types of land uses, such as “industrial,” “commercial,” “residential,” and so forth. Individual parcels of property are restricted to the uses that are permitted in their zone. The permitted uses can be either cumulative or noncumulative. Under cumulative zoning, uses are ranked in a hierarchy from most to least intensive, in accordance with their presumed incompatibility with single-family residences. Within any zone, one can devote one’s land to the designated use plus any less intensive uses. Thus, in a zone designated “commercial,” the owner could build a retail store but could also engage in less intensive uses such an apartment house, a two-family house, or a single-family home. Under noncumulative zoning, only the designated use is permitted. If a zone is designated “commercial,” only commercial buildings are permitted in that zone.

The theory behind Euclidean zoning is that separation of uses will enhance positive spillovers and minimize negative spillovers. Industrial plants will be segregated in one zone, commercial operations in another, apartment houses in yet a third, with single-family homes shielded from all these other uses. In upholding this kind of zoning against constitutional attack, the Supreme Court expressly recognized that zoning was designed to minimize nuisance-like incompatibilities, and that the protection of the single-family home was the dominant objective.

Euclidean zoning works best if it is adopted on a clean slate, before a community is developed. The zoning map, at least implicitly, is deemed to reflect a comprehensive plan for the community, and all development is supposed to unfold in accordance with this plan. When zoning became popular in the early decades of the twentieth century, however, it was adopted by many cities that were already largely developed. Layering the zones on top of existing neighborhoods was difficult, because often land uses were extremely intermixed. Courts ruled that municipalities could not “downzone” properties that had already been developed and devoted to a use that was incompatible with the zoning scheme. In some states, such “nonconforming uses,” as they are called, have been held to be constitutionally protected as vested rights. 28 In some communities, nonconforming uses are permanently grandfathered. In others, they have been given a finite period of time to continue operating, after which they had to be converted into a conforming use or abandoned. Either way, these nonconforming uses inevitably compromised the purity of the comprehensive plan. Interestingly, nonconforming use protection applies only to developed property. Raw land that has not been developed can be subject to severe zoning restrictions that impair its market value, without running afoul of constitutional limitations.

The judicial protection of nonconforming uses highlights the preventive nature of zoning regulation. When a court determines that some land use is a nuisance, or when a legislative body determines that a particular land use is a public nuisance, it is well established that the use can be eliminated, without any need to provide compensation to the owner of the property for losses associated with such action.29 Zoning is designed to prevent nuisance-like interferences, but does not rest on any finding that the owner actually is committing a nuisance. Courts have concluded that this preventive rationale is not sufficiently powerful to justify shutting down existing nonconforming uses, at least not with some kind of transitional relief.

Zoning, like covenants running with the land, frequently encounters problems associated with changed circumstances. What was once thought to be an ideal location for single-family homes comes to be an area more appropriate for multifamily homes, or perhaps for commercial development. Changes can be made in zoning rules either through obtaining a variance or special exception, or through an amendment to the zoning plan. Variances and special exceptions are usually relatively small changes that affect only one or a small number of properties. Variances are more discretionary and can often be granted by administrators or by zoning boards of appeals. Despite their name, special exceptions are given as of right as long as the landowner satisfies the criteria in the zoning ordinance. If a larger change is required, the zoning plan must be amended. Such amendments require action by the local legislature, and thus are harder to obtain.

Is zoning beneficial overall? This is hard to answer in the abstract. Zoning carries with it the costs of rigidity and artificial scarcity of land but may be more effective than nuisance or covenants in dealing with severe spillover problems — although nuisance and covenants have their defenders. The fact that incumbent homeowners favor zoning is not dispositive on the question of overall welfare: People squeezed out of the housing market because of zoning’s contribution to scarcity and higher cost do not have votes in local politics. At best, they are represented by developers who would like to cater to their demand. Recent empirical work suggests that in California and the urban Northeast, zoning increases housing prices significantly through artificial scarcity. In other areas, housing more directly reflects the costs of construction. 30

As zoning laws have grown older, problems of changed circumstances have become more acute. Frequent recourse to variances and amendments eventually led to a second conception of how zoning might work, which has come to be known as the planned unit development (PUD).

In contrast to Euclidean zoning, which is grounded in the idea of a comprehensive plan for the entire community devised by experts, the PUD is based on the idea of a negotiated bargain between developers and local political authorities.31 Typically, a developer will approach a city with a proposal to build a new subdivision or shopping center, or to redevelop an existing neighborhood. City authorities and the developer will then negotiate a plan for the development, including not just private spaces such as houses, apartments, and commercial areas, but also open spaces, public parks, streets and sidewalks, and even schools and other community facilities. The city authorities are understood to have the power to veto the development, and they use this leverage to obtain promises that will provide benefits to the community. The developer, of course, can always back out of the project, and will use this leverage to try to maximize the economic return from the development. The result is a negotiated compromise, which generates the plan that governs the development, but does not affect other areas of the municipality.

PUDs reflect a very different philosophy about how to regulate externalities than the one reflected in Euclidean zoning. Whereas Euclidean zoning is based on a philosophy of separating uses into discrete zones, a PUD typically incorporates a mixture of different uses in one area. This is thought to generate a more vibrant, diverse community than Euclidean zoning, which tends toward homogeneity. Whereas Euclidean zoning is driven by a desire to achieve comprehensive and rational planning, imposed from above, PUDs are individually negotiated and yield a series of idiosyncratic projects that may or may not sum to a coherent whole. Whereas Euclidian zoning maintains a sharp distinction between public and private, with land use planning regarded as a public function governed by elections, laws, administrative rules, open meeting requirements, and judicial review, PUDs entail a mixture of public and private decision making, with some inevitable loss of transparency and public participation. Critics of Euclidean zoning hail PUDs as more flexible, realistic, and responsive to public needs. Critics of PUDs condemn them as a sell-out to interest-group influence at the expense of the general interest. The debate goes on, although the trend is clearly in the direction of greater use of PUDs.

Because zoning is a form of local regulation, there is nothing to ensure that the interests of outsiders are factored into the process. A particularly troubling claim is that zoning rules are designed, either deliberately or inadvertently, to exclude racial minorities and poor persons from locating in particular communities. For example, suburban communities often adopt zoning rules that require large minimum lot sizes for single family homes and impose extensive open space requirements, with little space allocated for apartments or multifamily units. The effect of such rules is to limit development to large, expensive homes that few minorities and no poor households can afford. The New Jersey courts have sought to combat these effects by holding that exclusionary zoning violates the state constitution, and by requiring communities to amend their ordinances to include more generous allocations for low- and moderate-income housing.32 These efforts at judicial reform have led to a prolonged tussle between the courts and the legislature over the proper remedy, with the result that the issue still remains unresolved. A few other states have made milder attempts to police exclusionary zoning,33 but most have ignored the issue.

One solution to the problem of exclusionary zoning would be to relocate land use planning functions from local governments to regional or state governments. This would allow a wider range of interests to be represented in the planning process. Such a shift in the level of regulation, however, would come with a sacrifice in detailed knowledge about local conditions and preferences. Moreover, there is little prospect that local communities will voluntarily relinquish their “right to exclude” any time soon, any more than individual property owners willingly give up their right to exclude, which is why the problem of externalities is so intractable.

Further Reading

Further ReadingR. H. Coase, The Problem of Social Cost, 3J.L. & ECON. 1 (1960) (pioneering study of the role of transaction costs in situations with externalities and propounding what later came to be known as the Coase theorem).

Guido Calabresi & A. Douglas Melamed, Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Inalienability: One View of the Cathedral, 85 HARV. L. REV. 1089 (1972) (seminal article introducing the distinction between property rules and liability rules).

Robert C. Ellickson, Alternatives to Zoning: Covenants, Nuisance Rules, and Fines as Land Use Controls, 40 U. CHI. L. REV. 681 (1973) (offering a comparative analysis of different legal mechanisms for regulating neighborhood effects).

WILLIAM A. FISCHEL, THE HOMEVOTER HYPOTHESIS (2001) (arguing that the political power of local landowners is the key to understanding land use regulation).

James E. Krier & Stewart J. Schwab, Property Rules and Liability Rules: The Cathedral in Another Light, 70 N.Y.U. L. REV. 440 (1995) (emphasizing the importance of the ex ante versus ex post perspectives in considering the choice between property rules and liability rules).

A. MITCHELL POLINSKY, AN INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND ECONOMICS ch. 1 (3d ed. 2003) (offering a clear introduction to the Coase theorem and the choice between property rules and liability rules).

1. James Q. Wilson & George L. Kelling, Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety, ATLANTIC MONTHLY, Mar. 1982, at 29, 31–32; see also Hope Corman & Naci Mocan, Carrots, Sticks, and Broken Windows, 48 J.L. & ECON. 235 (2005); but see BERNARD E. HARCOURT, ILLUSION OF ORDER: THE FALSE PROMISE OF BROKEN WINDOWS POLICING (2001).

2. R. H. Coase, The Problem of Social Cost, 3 J.L. & ECON. 1 (1960).

3. See Thomas W. Merrill & Henry E. Smith, The Morality of Property, 48 Wm. & MARY L. REV. 1849 (2007).

4. See Thomas W. Merrill, Trespass, Nuisance, and the Costs of Determining Property Rights, 14 J. LEGAL STUD. 13 (1985).

5. Guido Calabresi & A. Douglas Melamed, Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Inalienability: One View of the Cathedral, 85 HARV. L. REV. 1089 (1972).

6. Henry E. Smith, Property and Property Rules, 79 N.Y.U. L. REV. 1719 (2004).

7. RESTATEMENT OF THE LAW SECOND, TORTS § 826(a) (1979).