10

The path to the scaffold

The power vacuum lasted for only a few hours. ‘At about 10 o’ clock King James was proclaimed in Cheapside by all the Council with great joy and triumph.’ This had been a long time coming and the Privy Council – sans Ralegh, of course – was ready for its crucial task of ensuring the peaceful installation of a successor to the childless Queen. The slick transfer of power after so many years of suppressed, whispered anxiety about the succession was a triumph for Robert Cecil and a relief for those who had feared ‘commotions’. The crowds were strangely quiet but this was interpreted, conveniently, as a mark of respect for the dead Queen. At least there was no violence; five hundred soldiers were levied in London for the coronation to ‘withstand any tumults and disorders’. ‘In an hour, two mighty nations were made one’, wrote Thomas Dekker; the union of Scotland and England had been achieved. He also noted, less complacently, that ‘some English great ones that before seemed tame, on the sudden turned wild’.

Ralegh was one. He joined the hordes of courtiers riding north, hoping to be among the first to be noticed and favoured by King James. But, in an ominous move, he was stopped in his tracks by Robert Cecil and forced to return to London. Cobham was also frozen out: Lord Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton, was already at the King’s side in Scotland and, according to one letter-writer, working ‘to possess the king’s ear and countermine the Lord Cobham’. Howard, in person, repeated the message of his letters, possessing the King’s ear with an image of Elizabeth’s court as ‘a world…of fractions’, of vicious cabals working tirelessly against each other. Days into the new regime, things did not look good for Ralegh. He moved swiftly to seal the deed that conveyed the Sherborne estate to trustees.

His actions suggest that, in March, Ralegh still hoped (foolishly, optimistically) that the new King might look favourably on him or, failing that, that the new King’s wife might look favourably on Lady Ralegh. Her opportunity came in mid-April. King James, having travelled as far south as Yorkshire, gave orders that ‘some of the ladies of all degrees who were about the [old] Queen…or some others whom you shall think meetest and most willing and able to abide travel’ should travel north to meet his Queen, Anne of Denmark. Lady Ralegh had most certainly been ‘about’ the old Queen and had shown she was ‘willing and able to abide travel’. James’s letter was, however, addressed to Robert Cecil, who was in no mood to do the Raleghs any favours. Bess was not on the guest list.

Lady Anne Clifford was, and she gives a graphic account of her participation in the struggle to be the first to meet the new Queen. First there is a problem about horses, which delays Anne and her mother, but once they are mounted there is no stopping them as they attempt to catch up with the main party. ‘My Mother & I went on our journey to overtake her, & killed three Horses that day with extremities of heat.’ They arrive late at night at a great house ‘where we found the doors shut & none in the House, but one Servant who only had the Keys of the Hall, so that we were forced to lie in the Hall all night till towards morning, at which time came a Man and let us into the Higher Rooms where we slept 3 or 4 hours’. In the morning they were off again, still hoping to be amongst the first to greet England’s new Queen Anne in her progress south. However quickly they travelled and however many horses were sacrificed to their political ambitions, the ‘diverse ladies of honour’ nevertheless had to halt their journey just south of the Scottish border. News filtered through that Queen Anne had suffered a miscarriage. She was not well enough to travel out of Scotland.

Some of the aspiring ladies used their initiative. The Countess of Kildare, wife of Lord Cobham (but, to complicate matters, no friend to Lady Ralegh or her husband), ‘quit her companions at Berwick and went to Edinburgh’, where Anne was due to make her first appearance after the miscarriage. The Countess’s initiative seemed to pay dividends, because even before the Queen crossed the border at Berwick on 6 June, Kildare had been appointed governess to the young Princess Elizabeth, King James and Queen Anne’s only daughter. Anne then travelled slowly south towards her new court in Westminster.

Bess, obviously not one of Cecil’s chosen few, did her best under the circumstances. She rode north, belatedly. Did she know that Robert Cecil was recording her every move? The very man she begged to accompany her to meet the new Queen was Cecil’s spy. He later wrote to his real master: ‘I was entreated by his wife to ride another idle journey to my charge to meet the Queen, where she received but idle graces’. Queen Anne was clearly either unwilling or unable to offer Bess any support. ‘Idle graces’ were not what was needed as spring turned to summer in 1603.

Ralegh was not having much more success. Prevented from gaining physical access to James, Sir Walter attempted to write to his King. On 25 April 1603, an informer reported back to the increasingly powerful Robert Cecil that Ralegh’s opinions ‘hath taken no great root here’ although his letters had indeed been presented to the King.

It is possible that Ralegh succeeded in meeting James. The diarist John Aubrey, writing decades later, tells of an encounter between the two men at Burghley House near Stamford. There is no other evidence for the meeting but as Aubrey tells it, both James and Ralegh are utterly recognisable as characters. Suffice to say the story does not involve a meeting of minds. James commented that he could, if necessary, carry the country by force. Ralegh, conveniently ‘walking close by’, suggested the matter should be put to the test. The King, understandably nonplussed by the proposition (he might have been expecting a flattering courtier to reassure him that there was no need for bloodshed, such was the universal affection for the new King), asked Ralegh to explain himself, which he promptly did: ‘Because that then you would have known your friends from your foes’. Aubrey says the comment was ‘never forgotten or forgiven’. James’s mind had already been poisoned against Sir Walter, thanks to Howard and Cecil, something the King allegedly admitted to Ralegh’s face: ‘O my soul, mon, I have heard rawly of thee’. These words offer both an indication of James’s accent and a reminder of how Ralegh’s name was pronounced by a Scot.

If Ralegh didn’t realise at this stage he had been stitched up by his enemies, he never would. He then made a bad situation worse by advocating war with Spain. The shifting political sands in the spring of 1603 are nowhere more visible than in England’s conflict with Spain, begun in 1585. James, as potential successor to Elizabeth, had been a staunch opponent of peace; his opposition rooted in his anxiety about the claims of the Archduchess Isabella, the Spanish Infanta, to the English throne. This created an opportunity, before Elizabeth’s death, for men such as Howard to damn Ralegh and Cobham as supporters of a deal ‘in the matter of this peace’. Once installed as King of England, James was far more conciliatory towards Spain: there would be no Queen Isabella. The irony of course is that Ralegh, a long-standing military hawk, was just as wary as James was of Philip III of Spain’s plans to place his daughter on the English throne and even more wary of those English courtiers who seemed to welcome the idea. Ralegh, like Essex before him, did not trust the peacemakers. Always a political outsider, despite his wealth, achievements and service to the Crown, Ralegh was now well and truly on the margins. Was it at this point that he began to consider a more dangerous way back to power? For the moment, he turned – once more – to writing.

Despite James being newly pro-Spain, Ralegh put together his arguments for active intervention on behalf of the Netherlands against Spain in A Discourse touching a war with Spain. His reasons were pragmatic rather than ideological. The Netherlands was unable to defend itself, so would be forced to turn to another country for protection. It was best that country be England. In another typical move, Ralegh ends the tract with a defence of the honest adviser, the man who tells truth to power, a necessary part of any monarch’s court. Those who remain silent when they can ‘declare’ and ‘publish’ their advice are no better than those who flee the kingdom, he writes. He might have been better off fleeing.

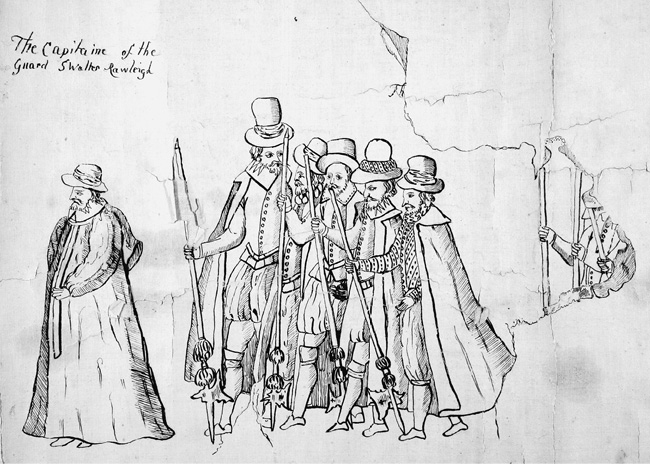

For a brief moment, Ralegh remained an ostensibly powerful, and highly visible, figure. His position as Captain of the Guard meant that at Queen Elizabeth’s funeral he walked at the head of his 150 ‘men of the guard, with the points of their halberts downwards’.

But it all unravelled very swiftly. First, Ralegh was stripped of the Captaincy of the Guard. In May, he lost his control of monopolies. Worse was to come. On 31st May, Ralegh was given notice to leave Durham House, another indication that others had succeeded where he had failed in the crucial months after James was proclaimed King. The Bishop of Durham had preached sermons to James at Berwick on 6 April and at Newcastle on 10 April, with the happy result of the return of the palace to his possession. Ralegh was given notice to leave by 24 June and warned not to remove any panelling, glass or metalwork. The ‘stables and garden’ were taken over by the ascendant Robert Cecil, who planned to clear them to make space for his ‘New Exchange’. All that Ralegh could retort was that even the poorest man would have been given three months’ notice and the whole process was ‘contrary to honour, to custom, and to civility’. He had held the house for nearly twenty years and had spent nearly £2,000 of his own money on it. He had ‘made provisions for 40 persons in the spring’ and has a ‘family (that is, a household) of no less number and the like for almost 20 horse’. He thinks it ‘very strange’.

Ralegh at the head of the Queen’s Guard during her funeral procession

No one was listening.

15 July 1603: George Brooke confesses. The Cinque Ports are closed and proclamations issued for the arrest of the conspirators. Men are being tortured. Thomas Gayton, writing from Gray’s Inn to his wife, notes that he’s bought the cloth she wanted and that Anthony Copley has been racked. Wild stories are the stuff of this summer: news of the King’s death briefly circulates, and is swiftly quashed. Ralegh is placed under house arrest; his keeper Thomas Bodley, his temporary home Bodley’s house in Fulham, west of London. The Crown has only hearsay evidence about a plot to overthrow James but it is enough to justify an interrogation of Cobham, who cracks. Cobham admits that he had intended to inspire rebellion and bring about a Spanish invasion. The result? The death of the King and the placing of Arbella Stuart on the throne. His co-conspirator? Sir Walter Ralegh.

Ralegh’s nerve is being severely tested and he does not handle it well. Asked about his involvement with Cobham, he makes the mistake of claiming different things, one after the other: he first denies any knowledge, then hints at his suspicions (clearly attempting to extricate himself by pointing at others) and then, most damningly, gets in touch with Cobham to reassure him that he had not revealed anything incriminating.

It was never going to turn out well. On 19 July Ralegh was moved to the Tower of London. A day later, Cobham was informed of Ralegh’s double-dealing towards him: ‘O wretch, O traitor’ he cried, with ‘many exclamations and oaths’ against Ralegh. More details emerged. The two men were planning to go to Flanders before travelling to Spain, where they would get ‘five or six hundred thousand crowns’ (600,000 crowns equates to an astonishing £150,000 in the present day, and this an era when most people never even had one crown in their hand). Then they would meet in Jersey, where Ralegh was governor. The plan, which always had a back-of-an-envelope quality, was that ‘they would take advantage of the discontentments of the people and thereupon resolve what was to be done’.

Cobham’s confession made clear that there were two, very loosely connected, plots. The goal of what was now deemed the secondary, or so-called ‘Bye Plot’, was to force a degree of religious toleration. It brought together such unlikely bedfellows as radical, sectarian Protestants and Catholic priests, both groups seeking a measure of freedom to practise their religion. The more ambitious, and deadly, aim of the ‘Main Plot’ was to stir up rebellion, invite a foreign invasion, kill the King and his two sons and put a puppet (and conveniently female) monarch, the young Lady Arbella Stuart, on the throne. The huge sums of money necessary to achieve these goals were, it was claimed, being raised by Ralegh and Cobham by means of the Spanish envoy, the Count of Arenberg. Ralegh and Cobham? No, said Cobham. He would never have done anything without Ralegh’s ‘instigation’. The man ‘would never let him alone’.

It was damning (and plausible) stuff. There were only two problems. One, the state had no material evidence. Ralegh had learned a little over the years about the dangers of putting things in writing. And, two, almost immediately, Cobham retracted almost every word of his confession. Over the following four months, Cobham, remarkably, refused to repeat his accusations, which meant that the Crown, seeking prosecution, would have to rely on ‘certified statements’ if it came to trial.

Perhaps it would not come to that. Ralegh, in his own mind the victim, besieged by ‘persecutors and accusers’ and ‘overthrown’ by them, was in complete despair. He ‘stood still upon his innocency, but with a mind the most dejected I ever saw’, wrote the Lieutenant of the Tower, reporting to his superiors. It got worse. Two days later, the Lieutenant is losing all patience: ‘I never saw so strange a dejected mind as is in Sir Walter Ralegh. I am exceedingly cumbered with him, 5 or 6 times in a day he sendeth for me in such passions as I see his fortitude is [not] competent to support his grief.’

While Ralegh’s abandoned any pretence at ‘fortitude’, his family remained both traumatised and under threat. Henry Howard, for one, was determined to bring both the Raleghs down, warning Lady Ralegh against any attempt to exonerate her treacherous husband. Torn between painting Bess as a devious conspirator (has she an ‘unspotted conscience’, he wonders) and as a foolish woman standing by her man, Howard points out that before she ‘conclude him to be a martyr’, Lady Ralegh must prove Sir Walter’s innocence. If she proved his innocence, however, then she charged ‘the state it self with injustice’.

Arthur Throckmorton, Bess’ brother, forwarded a letter from her to Robert Cecil on 23 July. His covering letter, written from his estate in Northamptonshire, reeks of understandable fear for himself and his sister. Unlike Bess, he is wary of showing support for Sir Walter: all he wishes to do is offer simple brotherly support to a ‘sorrowful sister’ in her time of need, to share their correspondence because he hopes it will show that they are innocent bystanders. All he asks is that he should be given ‘leave to come up unto her’ to give her ‘the lawful brotherly comforts I may’.

While waiting to hear if her brother would be allowed to come to her, Bess received a devastating letter from her husband. He can no longer bear to live and instructs his wife how to continue once he is dead, ‘for his sake who will be cruel to himself to preserve thee’. Ralegh was not going to wait for trial and execution. Suicide was the only way to escape the dishonour he had brought on himself and his family, the only decent thing he could do. He justifies himself knowing full well that ‘it is forbidden to destroy ourselves’ but arguing that he did not despair of God’s mercy: ‘Be not dismayed that I died in despair of God’s mercies, strive not to dispute it but assure thy self that God hath not left me nor Satan tempted me’. The implication is that he did, in contrast, despair of any mercy from the King: ‘Oh God I cannot resist these thoughts’. He hopes that death will bring ‘dark forgetfulness’ and longs to be released from torment: ‘O death destroy my memory which is my tormentor: my thoughts and my life cannot dwell in one body’.

What he does not ask of himself, he asks of his wife. She must go on living, she must learn to forget, she must endure the dishonour and she must marry again, if only to pay the bills.

Biographers and historians have been stern about this letter, no doubt partly because of the continuing taboos and unease surrounding suicide and depression but partly because of what has been viewed as its crass, even ‘effeminate’, emotionalism. It has been seen as essentially a fake, a performance designed to draw attention to Ralegh’s predicament, ‘nauseating and meaningless’.

The letter was not an empty threat: Sir Walter stabbed himself in the heart with a table knife. His contemporaries were as harsh on him as later historians. It was all for show. It was only a flesh wound. Ralegh’s attempted suicide was merely another sign of his guilt and of his weakness as a man. Interrogation and torture had succeeded in its purpose: ‘the property of the rack is not only to stretch the joints, but reach the conscience, and make it give’, wrote one observer, while the King suggested that Ralegh needed to be forcefully reminded that it was the state that would decide what happened to his body, not the traitor.

Ralegh did not die. By early August, he was recovering in mind and body, having worked out that his only problem was Cobham’s retracted statement. Others knew this already. Robert Cecil wrote to the English ambassador in France that Cobham ‘seems now to clear Sir Walter in most things and to take all the burden to himself’. Cecil knew that, in legal terms, a single witness could not bring about the conviction of a suspected traitor. The Crown therefore redoubled their efforts to get more dirt on Ralegh, examining suspect after suspect.

That summer of 1603, thousands were dying of plague each week in London. Thirty thousand would die in this epidemic, mainly from the poorer classes, as the disease did its deadly work in the overcrowded parishes just outside the city gates. As one of Shakespeare’s rivals, Thomas Dekker, expressed it: ‘Death (like a Spanish Leaguer or rather like stalking Tamberlane) hath pitched his tent in the sinfully polluted suburbs’. Unable to understand the indiscriminate disease, contemporaries could only view plague as a sign of God’s displeasure. It was an apocalyptic backdrop to Ralegh’s fall.

Plague would not stop the Crown’s quest. It did, however, ensure the postponement of James VI and I’s ceremonial entry into London, the withdrawal of the political elite from London, the delay of the start of the law term and the relocation of the law courts to Winchester, some seventy miles south-west of the capital. King James and his court settled at Wilton, near Salisbury.

September. The outlook was brighter for the prisoner. The judges met to discuss the case and acknowledged that Ralegh might escape punishment because the proofs ‘are not so pregnant’ in his case. Nevertheless, the political will remained: there was ‘a strong purpose to proceed severely in the matter, against the principal persons’.

By October, Ralegh’s opponents were again confident. Robert Cecil was sure that the accusation was ‘well founded’ and the ‘retraction so blemished’ that the outcome was a formality. Even more tellingly, Lady Ralegh was making plans for the inevitable death of her husband (attempting to obtain ‘a gift of all his goods’, even though it would not even begin to cover his debts). Nevertheless, she continued to seek a last chance for Sir Walter: ‘my Lady Ralegh hath offered £5,000 to bring her husband’s business to a Star Chamber’. This step revealed both her knowledge of the legal system and her willingness to pursue extreme courses of action. The court of the Star Chamber was even then an anomaly in the justice system; a jury-less court that did not obey English common law and that was presided over by the Privy Council and two judges appointed by the King. Crucially, however, although to be tried in Star Chamber was to acknowledge the guilt of the offender even before the trial started, the court could not impose a death sentence.

By the end of the month, it is not worth counting the dead in London; plague was doing its work. Ralegh writes to Cecil, begging for mercy. He knows who really matters now. All he can do is to make a passing appeal to the past (‘To speak of former times it were needless’ but, oh, how he needs Cecil to remember those past times) and to beg. He writes to Queen Anne. He writes to King James.

All to no avail. The decision was made to bring all the prisoners south to Winchester, partly because of the plague, partly because the King was already in Hampshire, suitably close to what would be the first show trials of his reign and partly because tensions were running high in London. Traitor Ralegh, ‘the best hated man in England’, a ‘viper of hell’, was so unpopular it was believed his trial might incite mob violence. It was ‘hob or nob’ (touch and go) whether the authorities would be able to bring the prisoner alive ‘through such multitudes of unruly people’. And indeed, on 13 November, there was a riot in London directed against Ralegh.

It was time to move him. As the prisoners travelled to Winchester, crossing Hounslow Heath, south-west of London, Sir Walter saw an old man and recognised him as someone to whom he owed money. He asked for the coach to be halted, announced his debt and asked, formally, for the King to ‘be good to this worthy gentleman’.

This small but powerful gesture is just as significant to an understanding of the man as the waves of hatred directed towards him. Every ounce of Ralegh’s charm, every ounce of his ability to use language, to perform on the grandest of stages, the qualities on show on Hounslow Heath in a small way, would be needed when on trial for his life. It would literally be a performance, because trials were public, theatrical spectacles, with seats going for high prices. It did not matter that there was no clear-cut case and that the prosecution was far from straightforward. What mattered was that it was Ralegh.

The setting was the thirteenth-century Great Hall, or Arthur’s Hall, of Winchester Castle. It is an imposing, profoundly atmospheric space that survives intact (complete with its Round Table) although the rest of the castle, the casualty first of civil war then urban development, has almost entirely disappeared.

Proceedings began on 17 November. The charge against Ralegh was based on Cobham’s (retracted) testimony from 20 July. The court was told that Sir Walter had conspired ‘to deprive the king of his government…to raise up sedition within the Realm, to alter Religion…to bring in the Romish superstition, and to procure foreign enemies to invade the kingdoms’. Furthermore, he had sought to place Arbella Stuart on the throne, for which he would receive £600,000, before retreating to safety in Jersey.

No one could question his fortitude now. Ralegh was in his element. He ‘sat upon a stool within a place made of purpose for the prisoner to be in, and expected the coming of the Lords, during which time he saluted divers of his acquaintance with a very steadfast and cheerful countenance’. Exuding confidence, he refused to challenge the composition of the jury: ‘I know my own innocency and therefore will challenge none. All are indifferent to me’. Behind the scenes, Lady Ralegh was less indifferent. She had worked tirelessly to find a sympathetic jury and succeeded in putting in two of her connections. Then, overnight, the jury was changed: her attempt had failed. Her husband remained master of the situation and of himself: ‘humble, yet not prostrate; dutiful, yet not dejected [to the Lords], towards the jury affable, but not fawning; not in despair nor believing, but hoping in them, carefully persuading them with reasons, not distemperately importuning them with conjurations; rather showing love of life, than fear of death’. If he lost his temper, it was always strategic. If this were a show trial, a way of establishing the power of the new regime, Ralegh was taking over the show.

It became obvious that the prosecutor Edward Coke was being forced into attacking Ralegh’s character because of the legal weaknesses in the Crown’s case. Coke behaved ‘violently and bitterly’, attempting to provoke Ralegh by calling him a ‘monster’, ‘viper’, ‘odious fellow’, ‘the rankest traitor in all England’, a ‘spider of Hell’. The more Coke ranted, the more the ‘standers by’ questioned his authority. Ralegh countered with common sense and relentless denials. He had never said he would make away with the ‘king and his cubs’. The charges made little economic or political sense, since Spain was bankrupt and would not waste money attempting to destabilise England. Ralegh was also winning the personality contest. He was no peasant traitor; was he ‘a Cade? A Kett? A Jack Straw?’ Of course not.

Ralegh’s priority was to discredit Cobham’s statement of 20 July. He made it clear that Cobham had ‘passions of such violence that his best friends could never temper them’. But he also knew that there was a serious fault line in the prosecution’s case, because two witnesses were required to make a charge of treason stick. Ralegh had done his legal, not to mention his theological, homework, aided by his friend Thomas Harriot. If the court accepted (and they could hardly not) that ‘the law of God liveth for ever’, then Ralegh could prove that ‘by the whole consent of the Scripture’, a conviction on the word on one person was insufficient. An alternative interpretation placed the treason legislation enacted by parliament over the previous 250 years above scripture. The Crown’s case was that, if a statute had lapsed, as it had done, then common law and common sense prevailed: one witness was enough.

Ralegh’s command of the occasion meant that only his voice was heard. ‘You tell me of one witness, let me have him’ he cried. He threw English precedent, Daniel and Deuteronomy at his audience. He demanded that his accuser be brought into the court. If they did not bring Cobham, then his trial would be by ‘not law but by the Spanish inquisition’. He cast himself, expertly, as the underdog, ‘weak of memory and feeble as you see’, a man without legal training. Would anyone present want to be tried on the basis of ‘suspicion and inferences’? No one would be safe.

His coup de grâce was to produce a letter of exoneration from Cobham, which had been smuggled to him. Coke met fire with fire: he brought out a second statement from Cobham, confirming his damning, deadly accusations. Ralegh had been the ringleader, he had negotiated with foreign powers (not 600,000 crowns but a less spectacular, although still welcome, annual pension of £1,500, in return for foreign intelligence) and Ralegh had told Cobham, ‘coming from Greenwich one night’ that he had already passed on information. A statute of 1351 demonstrated that it was treason ‘to compass or imagine’ the death of a King. Ralegh’s imaginings damned him.

It was all over very quickly. The jury voted unanimously that the prisoner was guilty of treason. Sir Walter Ralegh was attaindered: condemned to death as a traitor, with all his civil rights and capacities extinguished. His entire estate, both real and personal, was forfeited to the Crown and his blood decreed to be corrupted. His son Walter would not, could not, inherit anything.

Sir Walter was told he would be hung, drawn and quartered. Lord Chief Justice Popham lectured the prisoner on the Christian faith and warned him to disregard the dangerous ideas of Thomas Harriot. Ralegh was dismissed as a ‘revenger’ and a man who had climbed too high.

He fought back as best he could. He asked that the proofs be shown to the King and insisted that the jury would live to regret their verdict. Then he ‘talked a while with the Lords in private’. As he was taken back to prison by the Sheriff, he walked ‘with admirable erection, yet in such as sort, as a condemned man should do’. His performance, even in defeat, had been impeccable. As the commentator Dudley Carleton observed, Ralegh:

served for a whole act, and played all the parts himself…He answered with that temper, wit, learning, courage, and judgment, that, save it went with the hazard of his life, it was the happiest day that ever he spent.

Carleton believes that if Ralegh’s name had not already been so tarnished, he would have been acquitted and concludes by reporting a bystander’s comment:

he was so led by the common hatred that he would have gone a hundred miles to see him hanged, he would, ere he parted, have gone a thousand to save his life. In one word, never was a man so hated and so popular in so short a time.

Ralegh remained convinced that he had been ‘strongly practiced against’. Did he have a point? In public, Robert Cecil spoke of Ralegh’s fall as a ‘tragedy’. Some have argued that, in private, the entire conspiracy was manufactured by Cecil to consolidate James’s power and bolster his own position, even at the expense of his brother-in-law, Lord Cobham. Certainly, the discovery of the plot led to a new, hard-line policy, with an edict drafted in July 1603 (although enacted only some seven months later) expelling all Roman Catholic clergy, ‘Jesuits, Seminaries and other Priests’, from James’s kingdom. Was this a new regime consolidating its power, manufacturing a threat, needing and thus finding scapegoats? Other historians are dismissive: it ‘would have been the height of daring, or folly, to have manufactured complex conspiracies, even had time, imagination and resources permitted such creativity’, writes Mark Nicholls. Most likely, Ralegh was fool enough to give the new monarchy all it needed; a few words spoken in anger ‘coming from Greenwich one night’.

Although Cecil almost certainly did not actively engineer Ralegh’s fall but he was not the man to prevent the final elimination of a potential political rival for the sake of a past friendship. And Lady Ralegh was not the woman to allow that final elimination to go unchallenged. Her letter to Cecil might be hard for a modern reader to follow in its original spelling, but to read it as it was written allows some of its terrible urgency to come through:

To the most honnerabell me Lord Cissell

If the greved Teares of an unfortunat woman may resevef ani fafor, or the unspekeabell sorros of my ded hart may resevef ani cumfort, then let my sorros cum before you wich if you trewly knew, I asur my selfe you wold pitti me, but most espescially your poour unfortunate frind ich relyeth holy on you honnorable and wontid fafor: I knoo in my owne soule wich sumthing knooeth his mind that he douth, and ever hath doon, noy unlly honered the king, but naturally loveth him, and god knooeth far: from him to wish him harme, but to have spent his life as soune for him, as ani cretuer leveng.

I most humly beseich your Honnar – even for god sake – to be good unto him; to onns more make him your cretur, your relifed frind; and dell with the Keng for him – for onn that is more worti of fafo than mani eles; having worthe, and onnesti, and wisdom to be a frind. pitti the name of your ancient frind on his poour littell cretuer wich may leve to honnor you. That wee all may life up ouer handes and hartes in prayer for you and youres, bind this ouer pooure famlies to prayes your honnar and wonted good natur let the hole world prayes your love to my my pour unfortunat hosban, for cristis sake, wich rewardeth [at this point, Lady Ralegh runs out of space on her sheet, so she moves to writing vertically in the margin] all mercies, pitti his just case; and god for his infeni marci bles you for ever, and worke in the king merci: I am not abell I protest befor god to stand on my trembling leges otherwies I wold have watted now on you: or be derectid holy by you: chee that will trewly honnar you in all misfortun

E Ralegh

Lady Ralegh can only beg ‘me lord’ Cecil in the name of God to make her husband live again. At the same time, the letter is thoroughly, and problematically, defiant. Nowhere does she acknowledge her husband’s guilt. Instead, she offers a litany of his virtues: worth, honesty, wisdom.

Cecil did not listen. He did not need to, because with Ralegh condemned to death, Cobham was willing to talk, putting the nails in Sir Walter’s coffin. Cobham recalled that some recent exchanges with Robert Cecil had left Ralegh ‘full of discontent’ on that night when he came from the court at Greenwich. Pushed to his limit (and that never took much), Ralegh had encouraged Cobham to negotiate with Arenberg that he should ‘advertise and advise the King of Spain to send an army against England to Milford Haven’. As Ralegh expressed it, ‘many more had been hanged for words than for deeds’, therefore he had nothing to lose by acting.

If, at Ralegh’s trial, Coke had known about the Milford Haven discussion he would have used it. This was new evidence but it changed very little. The rest was familiar: the Spanish pension of £1,500 a year, the quid pro quo of providing information if England were to threaten either Spain or the Low Countries.

Cobham clearly felt he had nothing to lose in the run-up to his own trial, which took place on 25 November. As a peer of the realm, he was tried by his fellow noblemen in the Court of the Lord Steward. There was no abuse from Coke but there was also no eloquent defiance from Cobham. Indeed, ‘never was seen so poor and abject a spirit’, who ‘heard his indictment with much fear and trembling’. Cobham attacked George Brooke, his own ‘viper’ brother, much to one onlooker’s disapproval: he ‘accused all his friends and so little excused himself’. A day later, it was the turn of another noble conspirator to be tried at Winchester: Thomas Grey, 15th Baron Grey of Wilton Grey, one of the evangelical Protestants drawn into the Bye Plot. This was different again; the devout Grey making ‘a long and eloquent speech’ that ‘held them the whole day, from eight in the morning until eight at night, in subtle traverses and escapes’. Grey was rebuked: he should not challenge the court. Only a week earlier, ‘the master of shifts’, Sir Walter Ralegh, had shown this to be futile.

Ralegh’s supporters were doing their best. It was open knowledge (a ‘pretty secret’) that the ‘lady of Pembroke hath written to her son Philip and charged him of all her blessings to employ his own credit and his friends and all he can do for Ralegh’s pardon’, but it was also open knowledge that ‘she does little good’. Ralegh himself made one last effort. On 27 November, he wrote to five Privy Counsellors, including Robert Cecil, pointing out that he was condemned by the ‘first accusation’ that has now disappeared. Therefore, if he were to be killed, he would be one who ‘perished innocent’. Ralegh throws everything into this letter, peppering his case with quotations from the Bible and even a mention of Christ (noticeably absent from the vast majority of his writings): ‘I do beseech you for his sake that shed his blood for us to think of this one argument’. He attacks Cobham, who has always ‘had a cruel desire to destroy me, hoping thereby to extenuate his own offences’ but also attempts to be magnanimous. It is a moment for charity, so Ralegh ‘will only for this time accuse his memory or mistaking’. And he restates his innocence, in both senses of the word. His only crime is ‘giving ear to some things and in taking on me to harken to the offer of money’. He ends by begging:

And if I may not beg a pardon, or a life, yet let me beg a time at the king’s merciful hands. Let me have one year to give to God in a prison and to serve him. I trust his pitiful nature will have compassion on my soul, and it is my soul that beggeth a time of the king.

The reality was that the only possible escape from the scaffold was a personal intervention by James. Ralegh had one more letter in him, to write to the King in a final attempt to save his life. Two versions of this letter survive, the one that reached James and an unsigned draft in Ralegh’s less neat hand. It begins superbly: ‘This being the first letter which ever your Majesty received from a dead man’. Did Ralegh really believe that he would be dead by the time James read the letter or did he hope that this final plea would prompt the King to an act of mercy?

James was not the only audience that Ralegh had in mind. The letter was copied and recopied, the scribes working from a third version that someone had made available for public consumption. Ralegh would not go quietly. The world would know of his innocence.

James read ‘every word’ of it (Cecil wrote to Ralegh’s keeper to let him know). And did nothing.