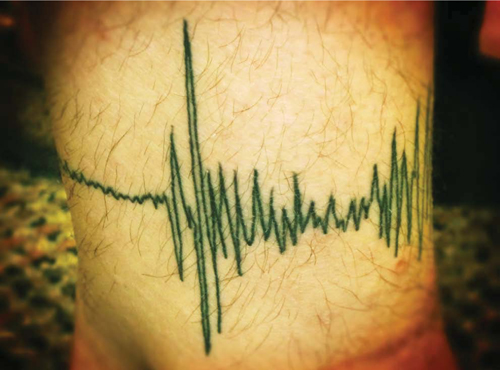

JULIAN LOZOS

Seismograph

“I’M A PH.D. STUDENT in earthquake physics (specifically, I work on fault dynamics),” writes Julian Lozos. “I have the seismogram of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake around my right ankle. That particular earthquake is not the actual subject of my research, but it was extremely important in terms of the development of theories on how faults work, and it was also instrumental in bringing me into the field of seismology to begin with.

“As to the first point: before 1906, people didn’t realize that earthquakes and faults had anything to do with each other. The 300-milelong surface rupture on the northern San Andreas Fault (a fault which had previously been identified only as a contact between rock types in San Mateo County, and which hadn’t been named) indicated that there was a connection. Observations of freshly-offset natural and manmade features along the fault led to the development of the elastic rebound theory: faults build up strain over time, and at a certain point, their ability to hold up under that strain is surpassed and they slip, causing an earthquake. Our understanding of the details of the earthquake cycle has become more complex since 1906, of course, but that basic theory still stands. Also, mapping of the 1906 rupture led to mapping the San Andreas through the rest of California, and to the discovery of many of the other major faults that cross the state. Both of these things do tie more directly into my work, since I do numerical models of fault dynamics, specifically in settings where multiple faults interact.

“As to the second point: I came into earth science via a very bizarre route. I always had an interest in earthquakes and volcanoes when I was little, growing up in the Washington DC area. Not sure where the interest came from, but it was there in the background for a long time. My undergraduate studies were in music, however, and when I was done with that, I headed to music grad school in California. I made the decision to move across the country around the time of the centennial of the 1906 earthquake, and reading newspaper articles about the anniversary reminded me that I was moving to earthquake country. I figured that learning more about earthquakes was the responsible thing to do if I was going to be living with them. The more I read, the more I remembered why I thought they were fascinating. The more I read, the more I wanted to know. I went out on road trips to visit the fault, I took a bunch of geology classes while working on my music degree, and through all of that, I was realizing that I didn’t enjoy music academia at all. I decided to apply to the earth science department, got in, and am thoroughly enjoying the research far more than I ever enjoyed music school. This was the right decision to make, I have no doubt, though I have to wonder if I would’ve started reading about quakes so intently if the 1906 centennial hadn’t coincided with my decision to move to California.

“So, I can look at my ankle seismogram and be reminded of many important discoveries and realizations in my field, and of what sent me in the direction of this field to begin with. It also reminds me of the fabled Big One, the kind of earthquake that will happen again, which is why we need to understand the science as well as we can, in order to minimize the disaster that results from the inevitable rupture.”

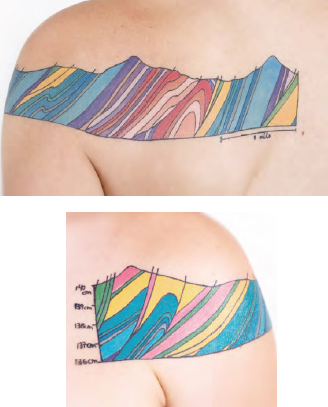

Cross-Section

“THIS TATTOO,” writes Helen Malenda “is a geologic cross section which was a final project for a structural geology course I had while studying a semester at Humboldt State University. It is a graphical representation of rock types found in a slice of a mountain chain, created from a geographical map of the ground surface.”

HELEN MALENDA

Cloud

A METEOROLOGIST WHO asked to remain anonymous writes: “This tattoo is of a cumulonimbus (thunderstorm) cloud with bolts of lightning. My childhood fascination with weather led to a career in it. Storms are embedded in my psyche & soul, and during a stormy time in my life I decided to embed a storm in my skin. I sketched a cumulonimbus cloud for the tattoo artist, and he and the other people in the parlor said something along the lines of, ‘Dude, we can make that tubular!’ And this is how it turned out. It retained meteorological accuracy via the bit of an ‘anvil’ in the upper right.”

Volcano

“AS A GEOLOGIST, and in respect to my temperament, I though a volcano tattoo would be just adequate,” writes Renate Schumacher, a German geologist.

RENATE SCHUMACHER

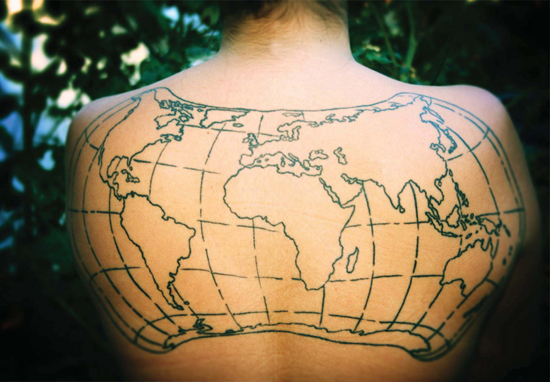

Strebe Projection

“ON MY BACK,” writes the geographer Marina Islas, “I have a map of the world. It is a Strebe Equal-area projection, polyconic. It took me a year to figure out which projection I wanted to live with for the rest of my life and I stumbled upon the Strebe projection. It’s very organic in shape and I appreciate that it is Afro-centric and not Euro- or Amer-centric.”

MARINA ISLAS

Tools of the Trade

“MY INTEREST IN geology started at an early age, while my mother was studying for her geology degree,” writes Jason Todd, a consulting geologist. “In lieu of daycare, she would set me up with an optical microscope and a stack of thin sections. Studying geology was almost priordained for me. I’ve spent the last 16 years of working in the field. As I worked my way up the corporate laddar, I spent less and less time in the field, but I have always devoted time to keeping the fundamental skills sharp. I have known hundreds of geologists and the most competent ones have the most complete understanding of the fundamental tools: rock hammer, compass and hand lens. My little sister began tatooing about 10 years ago, and when she worked this one up for me, I just couldn’t resist.”

JASON TODD