THIS MORNING I sat in the disheveled Jardin des Plantes reading Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem “Blue Hydrangea.” He describes the leaves as being “rough and dry” and the pretty umbels as being like “old blue letter-paper which the years / have touched with yellow, violet, and gray.” Rilke is said to have written his final drafts on old blue letter paper. This week, pondering the flowers—with their complex shadings of blue—in all the flower shops of Paris, I was reminded of how short life is but also of how tough and durable humans are.

I first encountered the Jardin des Plantes (opened in 1626 as a garden for medicinal plants) in Rilke’s 1903 poem “The Panther,” one of several he wrote about animals in captivity, in which he describes the panther’s gaze as being worn down by the bars of the cage: “His sight from ever gazing through the bars / has grown so blunt that it sees nothing more.”

Like me, the panther is a solitary traveler and he paces, as I sometimes do, with melancholy intensity. Then, suddenly, he opens his shining eyes and is pierced by the world:

Only sometimes when the pupil’s film

soundlessly opens . . . then one image fills

and glides through the quiet tension of the limbs

into the heart and ceases and is still.

(translation by C. F. MacIntyre)

In Rilke’s essay on Auguste Rodin, written the same year, he describes the sculptor’s visits to the Jardin des Plantes early in the morning to sketch the sleepy animals. Later, in Rodin’s studio on the rue de l’Université, he observes a tiny plaster cast of an antique wildcat that Rodin treasured: “There is a cast of a panther, of Greek workmanship, hardly as big as a hand. . . . If you look from the front under its body into the space formed by the four powerful soft paws, you seem to be looking into the depths of an Indian stone temple; so huge and all-inclusive does this work become.”

ON THE SOUTHWEST EDGE of the Luxembourg Gardens, there is a beekeeping school (rucher école) and a small sign warning of the danger of crossing bees. With their ornate metal roofs, the hives look like little Victorian houses.

There has been a beekeeping school in the garden since the last century, and one can buy delicious honey produced by the bees. Sometimes, passing by, I pull up a metal chair to read for an hour or two, and the bees are so numerous—buzzing as they work—that the sound is almost cerebral, as if the mechanism of my brain had been recorded and emitted through a speaker. On the morning when a hive queen chooses to be impregnated, she flies out of the shadows into sunlight, which she has never felt before, and because of the many dangers—birds, wind,insects—she is followed by an army of males, one of whom will intertwine briefly with her in flight. Then, back at the hive, the queen returns through curtains of golden wax and honey and is greeted by drones, who help her remove the entrails of her lover, including his organ, which she no longer has any use for, with his secretion deep inside her spermatheca.

IN FRENCH, one can say Je suis seul (I am alone) or Je me sens seul (I feel alone), but nothing as baldly distressing as “I am lonesome.” Or, even worse, “I am a loner.” My first poems were often about loneliness. My father was a military man and my brothers were athletes, so I was always looking for a different way to be a man. To look inward and explore the darker corners of the soul is one of the functions of lyric poetry. I think immediately of Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose poems I love. I hate having to apologize for, or defend, my inwardness. It was the American poet Marianne Moore who said that solitude was the cure for loneliness. Yet, if I spend too much time alone, I am called égoïste, or selfish. Surely it is impossible to be a good writer without being égoïste.

On her deathbed, Mother told me that she had been lonely all her life. Her twin died at birth. She lived through poverty and war. Her first baby died. Her husband left her. She worked hard but never seemed content. She had chronic back pain and became addicted to painkillers, which led to a mental break and suicide attempt, forcing her to be hospitalized. Still, she had a sense of humor and we laughed often when we were together. My last memory of her is of when she peeked out from under her covers to say goodbye. She’d become a Frenchwoman again, saying, “Je suis prête à m’allonger,” which means “I am ready to stretch out.”

THIS MORNING, walking down the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, I crossed the Seine into Les Halles (once the central market, or “belly,” of Paris) and stopped at the Centre Pompidou to see an installation by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, which consisted of a single, serene strand of lightbulbs looped against a pale wall.

What does it mean if a lightbulb burns out, I wondered? Is this a self-portrait? In 1996, Gonzalez-Torres died from AIDS-related complications. Is this a picture of his solitude? Was he égoïste, like me? In another minimalist work—“Untitled” (Perfect Lovers)—identical clocks are displayed, barely touching each other, on a light blue wall. A letter Gonzalez-Torres wrote to his partner, who died before him, explains one potential meaning for this work: “Don’t be afraid of the clocks, they are our time, time has been so generous to us. We imprinted time with the sweet taste of victory. . . . We are a product of the time, therefore we give back credit where it is due: time. We are synchronized, now and forever. I love you.”

LAST NIGHT I met James Lord again at his apartment and brought a bouquet of violet tulips, which he immediately placed in a vase on a side table in the living room. As I poured myself a scotch, he said that scotch and soda—or “fifty-fifty,” as it had been called—was his preferred drink for many years, but now it is Diet Coke. At Le Voltaire, on the quai Voltaire, we sat at the same table where we’d sat during our first meeting, and James pointed out something called oeuf mayonnaise “James” on the menu. Long ago, boiled eggs in mayonnaise had been one of his favorite things to order, and when it was removed from the menu he complained, so the owner resurrected it at the original price and named it in his honor. James encouraged me to order filet mignon, though it was expensive, insisting that “the poet of iron needs red meat now and then.” During our meal, he told me he’d gotten what he wanted from his life, and that he was content. He told me that meeting his partner, Gilles, had been the best thing to happen to him.

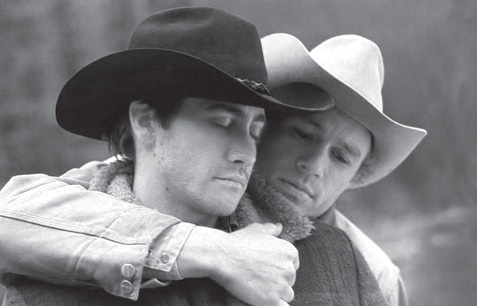

Again, we discussed Brokeback Mountain, the heartbreaking film about two ranch hands who carry on a sporadic affair, and whether it was a “universal love story,” as Hollywood wanted us to believe, or a gay tragedy recording the effects of homophobia. We agreed that it was not about love but instead about the damaging effects of the closet. Neither of us could bear to see it again.

In Annie Proulx’s story, she writes, “What Jack remembered and craved in a way he could neither help nor understand was the time that distant summer on Brokeback when Ennis had come up behind him and pulled him close, the silent embrace satisfying some shared and sexless hunger.”

TODAY I VISITED Deyrolle, the taxidermy shop in the seventh arrondissement on the rue du Bac, where one can buy a butterfly, beetle, baby lamb, or black bear. I came home with an Australian finch whose forehead, nape, and cap are pearl gray. He has black around the eyes, and his rump and underside are white, with pink flesh legs, and he wears a black bib.

Like me, he avoids populated areas and prefers the woodlands. His song is a soft hoarse whistling, and his cry of alarm is strangely sweet. He eats mostly seeds, but also flying insects, ants, and spiders. He is a gregarious drinker, taking long sips. In order to preserve him, I must twice a year “gently and softly clean him with a napkin moistened with white gasoline.” I’ve named him Keats, because he reminds me of the sonnet:

O Solitude! . . . it sure must be

Almost the highest bliss of human-kind,

When to thy haunts two kindred spirits flee.