THOUGH I HAVE a fear of heights, last night I rode La Grande Roue, the big wheel, in the Place de la Concorde, and afterward drank a glass of champagne to calm down. During the French Revolution the government erected a guillotine in the square and many important figures lost their heads there in front of cheering crowds. So it was given the name Concorde (meaning harmony, consensus, solidarity) after the convulsions of war. The wheel is situated at the entrance to the Tuileries Garden beside the giant Egyptian obelisk, where together they look like man and wife. The original wheel was built in 1900 and the cars were so large that they were used as homes for French families during World War I, when the region was devastated. With forty-two cars, it’s now the biggest wheel in France, and “green,” they say, with bright white LED lights and low CO2 emissions. Around and around and around I went, like a piece of chewing gum on a bicycle tire. But now and then, when my car rocked to and fro in the wind, it also felt like a cradle, and I could almost hear a voice singing, “There is no one, no one, but thee.”

ONE OF MY EARLIEST MEMORIES (was I three?) is of sitting at a kitchen table in Marseille while eating a warm, buttery croissant dunked in my grandmother’s bowl of café au lait. It was adulthood I was tasting, and love. Every morning, in every French city and town, there is the endless shriek of steam whistling, as if from another century, through shiny stainless-steel espresso machines. This morning, standing at a nearby café bar, I listened across time as the boiling water, under pressure, was forced through finely ground beans, and my shot was poured into a little bowl with piping hot milk and served with a pyramid of sugar cubes on a tin plate, each square as flawlessly cut as a stone block made by a mason for an aqueduct or a temple.

RÉVEILLONNER means to eat a dinner of saturnalian splendor on Christmas Eve, and I had my first réveillon many years ago with my mother’s younger brother, Uncle Gabriel, and his family in Marseille. Gabriel was a cobbler and sold shoes at the outdoor market, but his lungs were “like rotten sponges” from inhaling glue at the shoe factory, so he was living on a subsidy. Still, the meal dear Aunt Suzanne prepared was splendid.

To start, my uncle and I drank pastis, a high-proof anise-flavored liqueur that we diluted with water. Pastis emerged following a ban on the highly addictive absinthe, which was once known as “the green fairy” because of its pretty color and powerful effects as a muse-like alcohol. “I want to dance with the green fairy,” I told my uncle, taking my first sips of pastis. Absinthe was also the beverage favored by Baudelaire, who might have said about it what he writes about wine in his poem “The Poison” (“[It] can conceal a sordid room, / In rich,miraculous disguise, / And make such porticoes arise. . . .”), and other poets, like Verlaine, though it was banned in 1915 because of its psychoactive effects.

Our réveillon was served in small courses, including pâté, lobster, an assortment of cheeses, walnuts, hazelnuts, clementines, red wine, and champagne. Then, after dinner, Père Noël arrived with a sensible gift for everyone, though this was not the point of the gathering.

YESTERDAY, my friend Jenny Holzer, the American artist, and I wandered around the Louvre hunting for the still life The Skate, by Jean-Baptiste Chardin (1699–1779), in which a gutted ray fish with a human face hangs on a meat hook and is visited by a greedy cat. Chardin rarely left Paris and made a modest living producing work in various genres for whatever customers would pay. Eventually, Louis XV granted him a studio with living quarters at the Louvre.

Chaïm Soutine (1893–1943) admired the canvas so much that he painted his own version (Nature morte à la raie) after making pilgrimages to see it. I want to write poems that convey the same intense realism as this painting, in which Chardin proves that still life is not an inferior genre. He was breaking a mold. The work is meticulously observed, in the manner of Flemish painting, and unafraid of disgust. I like how food—an ugly sea creature—is its subject. No subject should be too low for a painting or a poem.

But is it possible that Chardin sees blue in his still life when there is really white? If so, is there more truth in the crockery and vegetables than in the grimacing ray? I don’t think so, because a painting, like a poem, can have emotional truth whether or not it is based on fact. The imagination is god. Still, why do I love this painting so? Is it because it’s conventional while being thought provoking, too? Is it because it says something true in an atmosphere of beauty? Sometimes, when I look at art, all I see is ambition. And the same is true with poetry, when ambition is larger than talent. This, in part, is why I’m drawn to the sonnet, with its lean, muscular, human-scale body.

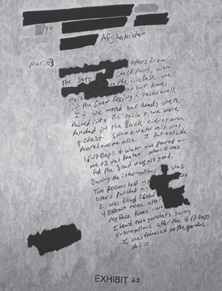

MY FRIEND JENNY is making paintings based on declassified, redacted documents from the war in Afghanistan in which prisoners describe being forced to kneel in the snow for many days while a snow-and-water mix is poured on them, and how during interrogations they were repeatedly punched in the face, chest, and flank. The testimonies are painful to read, but—unexpectedly—there is a formal dignity and beauty to the calligraphy and brushwork of Jenny’s oil paintings. The handwriting reminds us that in the Islamic faith the written word is of central importance, and that on the earliest pages of the Koran the pen and the writer are glorified.

Jenny and I wandered through the Louvre from one gallery to another, full of paintings by David, Ingres, and Géricault, and when we sat down on an old wooden bench to process what we’d seen, she told me the story of a foal that had been born that morning back home.

A healthy, perfect filly, she had a palomino coat. Last Christmas, the foal’s half brother had sneaked out to help make her. “Incest works better with ponies,” Jenny said drily, showing me a picture in which the unsteady foal is still wet from the insides of her mother.