WHEN THE GERMAN POET Rilke arrived in Paris, in 1902, he was so unhappy that he wrote, “Sometimes I lean my head against the gate of the Luxembourg just to breathe in a little space, calmness, moonlight—but there, too, it’s the same leaden air, still heavy with the perfume of the too many flowers they have crowded into the borders. . . . The city is just too vast and overburdened with melancholy.” Rilke’s mentor, the sculptor Auguste Rodin, advised the twenty-six-year-old that “you must choose one or the other, happiness or art.” But Rilke found Paris to be “bloated” with an “impatience to possess life immediately,” while he believed the real impulse of life was “calm, immense, elemental.” In this highly strung state, he considered Paris foreign, hostile, oppressive, febrile, and “close to death.” Rodin’s advice was to “work, nothing but work.”

“Everything has been said about these great churches,” Rilke wrote. “Victor Hugo penned some memorable pages on Notre-Dame in Paris, and yet the action of these cathedrals continues to exert itself, uncannily alive, inviolate, mysterious, surpassing the power of words. Notre-Dame grows each day, each time you see it again it seems even larger.” Rilke, with his youthful anxiety, found Paris to be “rushing headlong out of orbit, like a planet, toward some terrible cataclysm.” During his first days, all he saw behind the trees of the long avenues were “hospitals all over the place” and “long monotonous buildings.” He clung to the few things he regarded as different, like “the great old man,” Rodin, with whom things would end badly, and the sumptuous statue of Nike of Samothrace, at the Louvre, which made him feel the breath of Greece instead of the heavy, oppressive, mournful, solitary, dead air of Paris.

THIS EVENING AT MASS, there was a baptism of a small child, and I thought about how Rilke found Paris’s churches to be closer to nature than the public gardens, which were, for him, too much like works of art. Instead, he deemed the city’s big churches to be “uncannily alive,” with their solitude and calm that is “inviolate,” even in the middle of the metropolis. During our church service, a white-robed monk dipped the naked baby into a baptismal font three times, bathing him with water that his parents had brought from the Jordan River, which flows through Israel and Palestine. Then the baby—like a fish gripped at its head and foot—was lifted up into the altar’s bright spotlight so that all of us in the congregation could see his shining pink flesh.

After dusk, before the vespers candles are lit, I—an agnostic—always feel alone in the darkness of that heap of crumbling stone. A hand held in front of my face is invisible in the dank dark, where the only real light is the light of the imagination—until morning, when sunlight once again penetrates the stained-glass windows of the apostles, among them Matthew, the evangelist, who said, “Wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction. Strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, that leadeth unto life.” After the religious service, out in the square, there was a great drama after a handsome black-and-white duck escaped from a butcher’s shop. Three men with ladders, brooms, and stones were trying to capture the frightened creature, which plainly understood that it was soon to be eaten for Sunday dinner. I remembered the Jean de La Fontaine fable in which a drunken cook mistakenly thrusts a swan instead of a duck into his stew pot, and just as he is on the verge of cooking him, the swan’s melodic death song forces the cook to open his bleary eyes (“What have I done?”). A sensible man would never put such a fine crooner in his soup, he thinks. The lesson of the fable is that, when confronted with danger, a song (or poem) doesn’t do any harm at all.

MY FAMILY’S FIRST PET, when I was a boy, was a Siamese cat named Chou-Chou, which means “little cabbage,” though Chou-Chou was a muscular hunter who roamed the streets every night and left his trophies—lifeless sparrows and robins, mostly—on our doorstep. Sadly, one day, he didn’t return to us. Half a century later, to honor him, I’ve translated (from the French) an essay by Rilke about cats, written to accompany a suite of black ink drawings by his eleven-year-old friend Balthasar Klossowski, who became the Polish French modernist artist Balthus, whose mother was Rilke’s friend. When Balthus was a boy, he adopted a stray cat named Mitsou, and when the beloved Mitsou mysteriously disappeared, Balthus was so heartbroken that he commemorated the relationship in forty expressive drawings, which delighted Rilke—a sort of father figure—so much that he arranged for their publication. Rilke’s introduction begins:

Who knows cats? Is it possible that you really only claim to know them? I admit that for me their existence has always been a fairly risky proposition.

Animals, of course, must enter our world a little in order to belong to it. It is necessary for them to accept, no matter how small a part, our way of life and to tolerate it; otherwise, being either hostile or timid, they will grasp the distance between us, and this will become the basis of their connection.

Look at the dogs: their confident and admiring attitude is such that some of them appear to have renounced the oldest traditions of dogdom in order to worship our own customs and even our foibles. It is just this which renders them tragic and noble. Their choice to accept us forces them to dwell, so to speak, at the limits of their real natures, which they continually transcend with their human gazes and melancholy snouts.

But what is the demeanor of cats?—Cats are cats, briefly put, and their world is the world of cats through and through. They look at us, you say? But can you ever really know if they deign to hold your insignificant image for even a moment at the back of their retinas? Fixating on us, might they in fact be magically erasing us from their already full pupils? It is true that some of us let ourselves be taken in by their insistent and electric caresses. But these people should remember the strange, abrupt manner in which their favorite animal, distracted, turns off these effusions, which they’d presumed to be reciprocal. Even the privileged few, allowed close to cats, are rejected and disavowed many times.

RILKE WROTE in a letter, “The life of great men is a road bristling with thorns, for they are utterly dedicated to their art. Their own life is like an atrophied organ for which they have no further use.” Is it possible for a writer to love words more than life, I wonder? I don’t want my life to be an atrophied organ. I don’t want to be sidetracked from my dreams, like my father who enlisted as a soldier to escape the life of a sharecropper. Striving to assemble language into art, I don’t have an agenda for poetry, though I believe that too much skill can be boring in art.

A knack for writing verse doesn’t necessarily make one a good poet. What defines a poet is a certain universal quality that entails being attuned to the secret vibrations of the world; this does not always include a gift for versification, which is an aptitude practiced by many who are not truly poets.

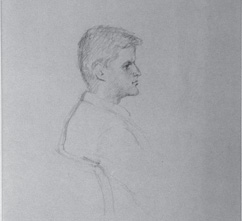

James Lord was—to me—a remarkable man whose life did not become atrophied, though his friends found him secretive and devious. He grasped the complex nature of artistic inspiration. He was cultivated without being a snob because he did not see the world hierarchically. There are drawings of him by the willfully enigmatic Balthus, whom he visited at his home, Château de Chassy, in Burgundy, where the sketches were completed—the first in fifteen or twenty minutes, then a second and a third, the final portrait, according to James, “decidedly the best.” “Well, now, my dear Jim, we shall have our little session of posing, shall we not?” Balthus had said to him when he came down from his studio carrying a large sketchbook and a handful of pencils. “Just sit in that armchair and face me. Good. Like that. And lower your head.” James thought that the sketches were among Balthus’s finest portrait drawings, and when he was leaving the château, Balthus told him, “You came all this way to pose for me, and I’ve very, very rarely done drawings of men. So it’s really I who owe you a favor. You must take all three and be on your way.” It was as if the drawings were a record not just of James’s youthful profile but also of the courteous nobleman Balthus’s revelation of something within himself, resulting from James’s intrusion into his solitary existence. “Balthus was a loner,” James insisted, a lordly, romantic loner, “who thought of the artist as a heroic, mythic figure.”

THE FIRST TIME I came to Paris, I was a little boy, and the memories I have come from my family’s Super 8 movies. In one, we are on a tour boat on the Seine, and I am seated next to my handsome father, who is wearing a summer suit with a white shirt buttoned at his throat. He is looking downward pensively. I am wearing a zippered gray jacket and squinting in the sunlight toward the camera. My older brother stands behind us with a sullen face. Death, fear, dream, and poetry are far away from the little boy I am. At the age of three, do I even have a self ? If so, how I must be striving to not be annihilated by Paris, which I find so overwhelming. My face looks solitary and calm. Behind us, the Seine is dark, reflecting the sunlight like a black mirror, instead of the murky gray water I crisscross in my comings and goings each day. The statues, parks, churches, fountains, and monuments await my young family and me. What perplexing messages memories can yield. As I write this, their odors, their shadows, and their sweet music are almost too much to bear.