Safariland 567-83 Model hip holster rides low, carries Glock 17 in this example.

The strong-side hip – i.e., the gun hand-side hip – is the odds-on choice for weapon placement for most of those who carry concealed handguns today. It is also the standard location for law enforcement officers in uniform. This is probably not coincidental.

Many ranges, police academies, and shooting schools will allow only strong-side holsters. The theory behind this is that cross draw (including shoulder and fanny pack carries) will cause the gun muzzles to cross other shooters and range officers when weapons are drawn or holstered. Some also worry about the safety of pocket draw and ankle draw. There are action shooting sports – PPC and IDPA, to name two – where anything but a strong-side belt holster is expressly forbidden. Once again, safety is the cited reason.

It is worthwhile to look at other such sports where cross draw holsters are allowed…but are seldom seen. In the early days of IPSC, cross draws actually dominated the winner’s circle for a while. Ray Chapman wore one when he captured the first world championship of the sport. Today, however, even though it’s still allowed, the cross draw has all but disappeared from that sport. A little history is in order. In the mid-1970s, a common IPSC start position was standing with hands clasped at centerline of the torso. With a front cross draw, this allowed the gun hand to be positioned barely above the pistol grip at the moment the start signal went off. IPSC started to go more toward hands-shoulder-high start positions (to give everyone a more level playing field, and to better allow range officers to see if a hand went prematurely to the gun), and the last such match I shot used mostly start positions with hands relaxed at the sides. These positions favored a gun on the same side as the dominant hand. In any case, a strong-side holster brings the gun on target faster because, standing properly, the weapon is already in line with the mark and does not have to be swept across the target.

We saw the same in NRA Action Shooting. Mickey Fowler for many years had a monopoly on the Bianchi Cup, using a front cross draw, specifically an ISI Competition Rig he and his colleague Mike Dalton had designed with Ted Blocker. However, in later years, the Cup has always been won with a straight-draw hip holster.

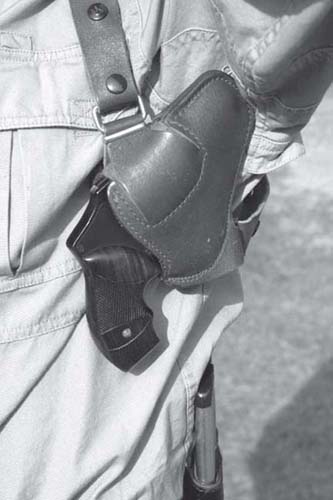

Quality concealed-carry hip holsters aren’t new. This one, carrying a period S&W Model 39 9mm…

…and was made by the great Chic Gaylord, whose timeless designs are now reproduced by Bell Charter Oak.

Because they begin at the academy with handguns on their dominant hand side, cops tend to stay with the same location for plainclothes wear. Habituation is a powerful thing. Master holster maker and historian John Bianchi invokes Bianchi’s Law: the same gun, in the same place, all the time. It makes the reactive draw second nature.

We saw this in action in the IPSC world in the late Seventies. The second American to become IPSC world champion was the great Ross Seyfried. Ross shot a Pachmayr Custom Colt Government Model 45 from a high-riding Milt Sparks #1AT holster that rode at an FBI tilt behind his right hip. He was a working cattleman in Colorado and a disciple of both Elmer Keith and Jeff Cooper. It was a time when the serious competitors mostly either went cross draw, or wore elaborate speed rigs low on the hip. One who chose the latter was a multimillionaire for whom IPSC was purely sport. Frustrated that Ross had beaten him at the national championships in Denver, this fellow hired a sports physiologist to explain to him how Seyfried had managed to beat him. “I don’t understand it,” the frustrated professional told the wealthy sportsman in essence after viewing tapes of Seyfried. “Your way is faster than his. The way this Seyfried fellow carries his gun is mechanically slower.”

What physiologist and rich guy alike had missed was one simple fact: the multi-millionaire only strapped on his fancy quick-draw holster on match day and at practice sessions. Ross Seyfried wore a #1AT Milt Sparks holster behind his hip every day of his life, though in the saddle on the ranch he carried a 4-inch Smith & Wesson Model 29 44 Magnum. Ross and that holster had developed a symbiotic relationship. Reaching to that spot had become second nature, and made him faster from there than a part-time pistol packer with a more sophisticated, more expensive “speed rig.”

Designed by the late Bruce Nelson, these rough-out Summer Special IWB holsters were produced by Milt Sparks. Left, standard version for Morris Custom Colt 45 automatic. Right, narrow belt loop model to go with corresponding thick but narrow dress belt for suits, also by Sparks, here with Browning Hi-Power.

If the navel is 12 o’clock, a properly worn concealment hip holster puts a right-handed man’s gun at 3:30. In this position, just behind the ileac crest of the pelvis, clothing comes down in a natural drape from the latissimus dorsi to cover the gun without bulge. On a guy of average build, the holstered gun finds itself nestled in a natural hollow below the kidney area. With the jacket opened in the front, the gun is usually invisible from the front. Being just behind the hip, a holstered gun in this location does not seem to get in the way of bucket seats nor most furniture, and doesn’t press into the body when the wearer leans back against a chair surface.

Because of its proximity to the gun hand, and because the gun can come directly up on target from the holster, the strong-side draw is naturally fast. For males, simply bringing the elbow straight back brings the hand almost automatically to the gun.

Women’s hips don’t adapt well to male-oriented holsters. Note where Julie Goloski carries her S&W M&P 9mm as she pauses while winning 2006 National Woman IDPA Champion title..

The hip draw does not lend itself to a surreptitious draw – that is, starting with the hand already on the gun, unnoticed – unless the practitioner can get the gun-side third of his body behind some concealing object or structure. Because of the higher, more flaring pelvis and shorter torso, women don’t find this carry nearly as comfortable or as fast as men. As noted elsewhere in this book, cross draw and shoulder carry seem more effective for many women.

Christine Cunningham, an instructor and competitor in the Pacific Northwest, is also a holster-maker. She specializes in “by women, for women” concealed carry gear. Her stuff is tops in quality and function, and very well thought out. You’ll find much good advice, as well as many useful products, at her website, www.womenshooters.com.

The gun behind the hip is positioned so as to be sensitive to exposure and bulge when the wearer bends down or leans forward. This simply means the practitioner has to learn different ways to perform these motions in public.

Exotic leathers have become a status symbol among CCW people. This ParaOrdnance SSP 45 automatic lives in this sharkskin OWB holster/belt combo by Aker.

Continuing with the “clock” concept, let’s look at different spots on the belt for holster placement. 12 o’clock, centerline of the abdomen, will be comfortable only with a small, short-barrel gun. It’s a quick and natural position, particularly for women thanks to their relatively higher belt-lines. My older daughter, tall and slender, prefers to carry her S&W Model 3913 9mm here, in an Alessi Talon inside the waistband holster, or a belly-band. It disappears under an untucked blouse, shirt, or sweater, but provides very fast access.

1 o’clock to 2 o’clock becomes the so-called “appendix position.” An open front garment must be kept fastened to keep it hidden, but a short-barrel gun works great here for access during fighting and grappling. A top trainer who is still active in undercover police work and teaches under the nickname “Southnarc” favors this location, with his retired cop father’s hammer-shrouded Colt Cobra 38 snub-nose inside the waistband at the appendix. It is very fast. Some top IPSC speed demons, such as Jerry “the Burner” Barnhart carry their competition guns in speed rigs at the same location. A small gun conceals well here under untucked closed-front garments. However, the appendix carry causes all but the shortest guns to dig into the juncture of thigh and groin when seated, and the muzzle is pointing at genitals and femoral artery. There are those of us who find this incongruous with our purposes for concealed carry, one of which is to prevent weapons being pointed at such vulnerable parts of our bodies.

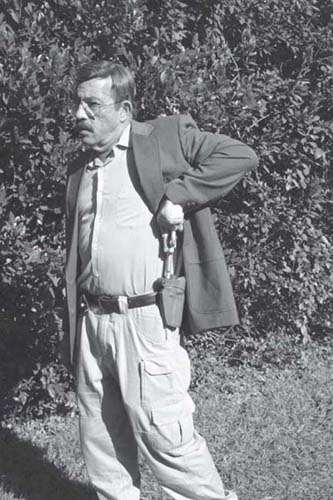

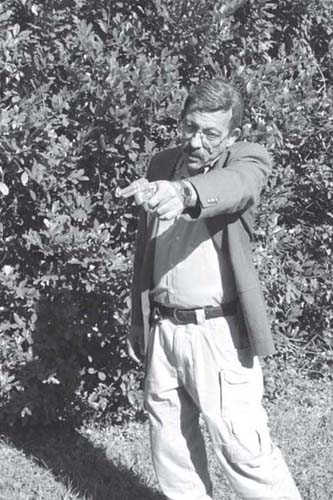

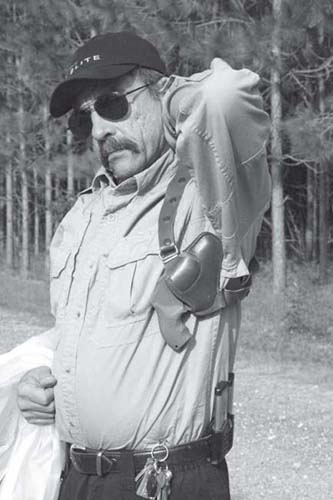

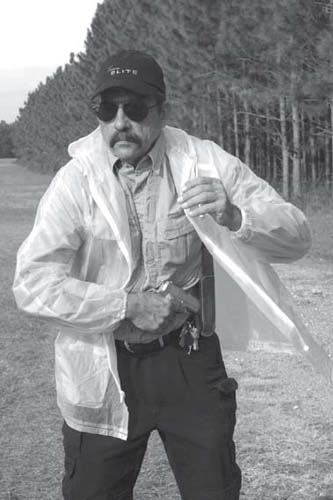

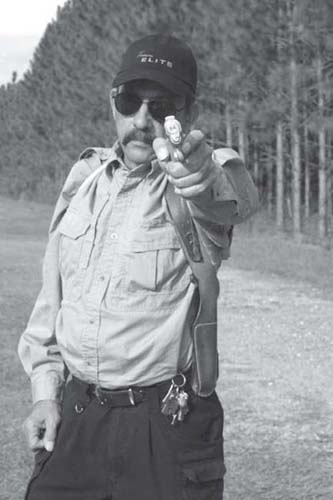

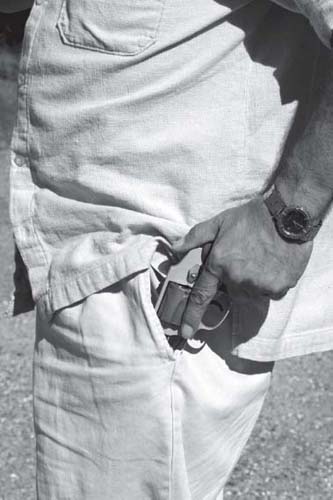

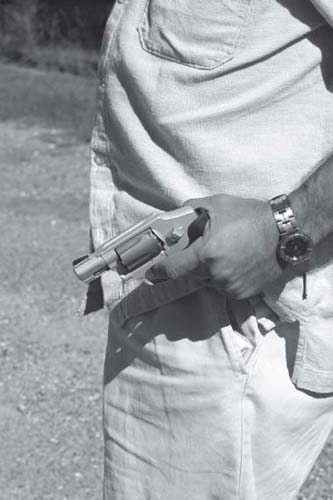

STREET TIP: When you feel the gun butt moving to the rear and “printing,” DON’T adjust it like this. It will be obvious to anyone in line of sight that you’re “carrying.” INSTEAD…

…use your forearm behind your back to push the gun forward, stretch back a little, and you look to the world like someone with a sore back, not someone carrying a gun.

Moving more to the side, the true 3 o’clock position is not ideal for all day concealed wear. Riding on the protuberance of the hip, the gun protrudes accordingly, calling attention to itself even under big, heavy coats. The holstered gun at 3 o’clock will grate mercilessly on the hip-bone. Cops get away with it in uniform because their holsters have orthopedically curved shanks, and the weight is distributed on their wide Sam Browne belts. Neither mitigating factor will be at work in a concealment holster.

3:30, just behind the hip, seems to be optimum for comfort, concealment, and speed. It’s where most professionals end up parking their holsters.

By the time you hit 4 o’clock, there is more likelihood of the butt protruding. When you hit 6 o’clock, the true MOB (middle of back) or SOB (small of back) position, you’re getting into dangerous territory. The SOB is an SOB in more ways than one. While accessible to either hand, it can be mercilessly uncomfortable when you are seated. The rear center hem is the first part of an outer garment that lifts when you bend forward or sit down. The gun butt can catch the hem and completely expose the holstered gun. You can’t see it and usually can’t feel it, meaning you’re the only one in the shopping mall who won’t know that your weapon is exposed.

Another extreme danger of this carry is that any fall that lands you flat on your back will be the equivalent of landing on a rock with your lumbar spine. Very serious injury can result.

Yet another problem with SOB carry is that you can’t exert any significant downward pressure to hold the gun in place when trying to counter a gun snatch attempt. Moreover, biomechanically, you are pretty much putting yourself in an armlock when drawing. As a rule of thumb, any technique that requires you to put yourself in an armlock when defending yourself is a technique you should probably re-evaluate.

Concealment Rig by Ted Blocker makes this full-size Glock 17 concealable for its average-size male owner.

An inside-the-waistband (IWB) holster will conceal the gun better. Simple as that. The drape of the pants from the waist down blends the shape of the holstered gun with that of the body. The hem of the concealing garment has to rise above the belt to reveal the hidden weapon. This carry allows average size guys like me to carry full-size service handguns concealed under nothing more than an opaque, untucked tee or polo shirt, one size large. Held tight to the body by belt pressure, this design minimizes bulge.

Some have tried IWB and found it uncomfortable. This is because their pants were sized for them, and now contain them – plus a holstered gun. For preliminary comfort testing, unbutton the pants at the waist and let out the belt a notch, and try it again. If it’s comfortable now, nature is telling you to let out the pants if possible, or start buying trousers two inches larger in the waist. As noted elsewhere here, this practice “keeps you honest” (i.e., keeps you carrying) because now the pants won’t fit right without the gun in its IWB holster.

Belt clips don’t secure as well as leather loops, for the most part. There are exceptions, such as the appropriately named Alessi Talon, the clips used by Blocker on their DA-2, and the modular Kydex clips on the Mach-2 Honorman holster. Cheaper IWB holsters are notorious for their poor clips.

The IWB holster stays in place largely through belt pressure, so you want a rigid holster mouth to keep the opening from collapsing and interfering with re-holstering. The classic Bianchi #3 Pistol Pocket, a Richard Nichols design, used stiff leather reinforcement for this. Most others followed the lead of the late Bruce Nelson in his famous Summer Special design, and used leather-covered steel inserts to keep the holster mouth open. On rigid Kydex, of course, the material does this by itself.

Inside the waistband, slimness becomes more important, one reason the flat Browning Hi-Power and 1911 pistols are so popular with those who prefer this carry format. The fatter the gun, the more the belt is pushed out from the body. This allows the pants to start sliding down in the holster area, causing frequent need for readjustment.

Because the gun is tight to the body, sometimes against bare skin or sweat-soaked shirts, many makers have built “shielding” into the design to protect the gun from sweat, and bare skin from sharp edges. This works pretty well, but can slow the thumb’s access to a perfect pre-draw grasp, depending on gun design and hand size.

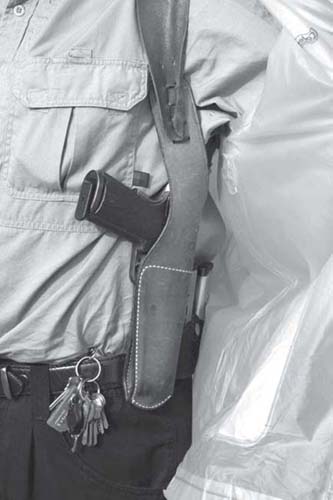

I’ve only designed two holsters in my life. Both were IWB. The first, designed with Ted Blocker, is the LFI Concealment Rig. It’s comprised of a dress gun belt lined with Velcro, and your choice of open top or thumb-break safety strap holster with coordinated Velcro tab. This lets the concealing garment ride all the way to the top edge of your belt without revealing anything, and perhaps more important, lets you adjust the holster almost infinitely for your particular needs: high, low, exact degree of rake (orientation of muzzle) and tilt (orientation of butt) that you want. High versus low is important if, like me, you have to switch between suit pants and uniform pants that tend to ride at the waist, and jeans/cords/BDUs that tend to ride slightly lower at the hips. Now the gun is in exactly the same where-you-want-it spot no matter what you’re wearing. The combination of Velcro shear factor and belt tension holds it in place. It’s very secure, and I’ve taught weapon retention classes with one without it coming loose. Matching magazine pouches are available, and the LFI Concealment Rig also works as a cross draw.

The other was designed for Mitch Rosen, at his request. He wanted an open-top rig that would carry a heavy, full-size fighting handgun without the weight of the loaded magazine in its butt tilting it backward to “print,” or expose itself through clothing. I designed an FBI-tilt IWB scabbard with a single strong belt loop at the rear, behind the gun, where the loop’s bulk wouldn’t add to the holster’s. In this position, the holster “levered” the gun forward and prevented it from tilting backwards. I called it the Rear Guard, because the loop at the rear guarded against rearward holster shifting. Mitch was kind enough to call it the Ayoob Rear Guard. It was shortened to ARG, which I’ve always pronounced as Ay-Arr-Gee. Unfortunately, folks started pronouncing the acronym in one syllable, which sounded like “Arrgghh.” I suppose I should just be glad I didn’t name it Super Holster Inside Trousers. After 9/11/01, Mitch changed the name to American Rear Guard. Still the same excellent holster, though.

The belly-band is a variation of inside-the-waistband carry, approximately four inches of elastic strapping with a gun pouch. It is worn best at belt level, “over the underwear and under the over-wear.” The first of these I ever saw was a John Bianchi prototype in Gun World magazine, circa 1960. Bianchi didn’t bring it out back then, but in a few years, a firm in Brooklyn named MMGR did. I wore an MMGR belly-band to my grad school tests one hot summer day when I was 21, and noticed the day I got home that the beautiful blue finish of my S&W Model 36 Chief Special had turned brown on the side next to my body. Some later belly-band designs, such as the Gould & Goodrich, used a separate plastic shield on the gun pouch to protect the weapon from this, but expect some degree of sweat exposure with this type of carry. The Tenifer finish of the Glock pistols seems to stand up to this best, followed by the similar Mellonite finish used on S&W M&P autos, followed by industrial hard chrome finishes and stainless. The Glocks will discolor after long carry in this fashion, but won’t actually rust.

While I prefer the belly-band in the front cross draw position for a 2-inch 38, larger guns work best behind the hip. They’re a great alternative under a tucked-in shirt for those who work in business suit environments and must take the suit coat off in the office, but can’t afford for the gun to become visible. A “Hackathorn rip” movement is the best drawing option here. I also know medical professionals in gun-free zones in high crime areas, who wear small handguns this way under their scrubs.

There are many good belly-bands. My personal favorite has always been the unfortunately discontinued Bianchi Ranger, with built-in money belt. It has been my companion all over the world. I’ve carried S&W 4-inch 44 Magnums in it, perfectly concealed on the streets in cities from South Africa to Europe.

Since they offer little protection against sharp edges, belly-bands work best with edge-free guns. That said, properly adjusted they can be incredibly comfortable. One downside to them, though, is that you practically need a shoe-horn to get the gun back in. The near-impossibility of quickly reholstering means that regular range practice is out of the question, and you have to have an action plan that includes putting the gun away in pocket or waistband after making a belly-band draw on the street.

The “tuckable” is a different breed, the latest development in this area and one of the most widely copied. It goes back to Dave Workman, a holster-maker who is also a leading Second Amendment advocate and gun author. For those with office dress codes, Dave came up with an inside the waistband holster that had a separate paddle that secured on the belt, creating a deep “V” between the holster and that securing portion, into which a dress shirt could be tucked. Worn at 3:30, or in the appendix position, or at 11 o’clock in a front cross draw, it hid the gun perfectly. The snap-on belt loop could be disguised as a key holder simply by putting a small key ring in the loop. When he looked for a larger manufacturer to handle the design, I steered Dave to Mitch Rosen, who introduced it to the world as The Workman. It instantly became the most copied new rig in the holster field. This style also functions perfectly well as an ordinary inside the waistband holster.

Another IWB variation that goes deep inside the waistband is the Pager Pal. A flat semi-disk of leather contains a small revolver or auto that rides inside the pants and below the belt, hooked onto the belt by a camouflaged pager, cell phone carrier, knife pouch, etc. When carried cross draw, the support hand grabs the pager or whatever and pulls upward, exposing the holster for the gun hand’s draw. I found that if you don’t have a large butt, you can carry it on your strong side behind the hip and knife the hand down inside the pants to get at the gun. Not my first choice, but an interesting option that some have found useful.

The Yaqui Slide is extremely popular for concealed carry. Here, the Galco version carries a custom .40 cal. Glock 23 with Caspian slide, BoMar sights, and Hybrid-Port recoil reduction system.

Outside-the-waistband (OWB) is more comfortable, but requires more effort for concealment. The most concealable designs copy to some degree the Pancake holsters of Roy Baker. Rounded, thus their eponymous shape, Baker’s holsters and some of today’s copies have three belt slots, one in the rear and two in the front. This allows the shooter to set up for forward “FBI” tilt, straight up hip-draw, or straight up cross draw. With the belt tensioning the holster fore and aft of the actual scabbard body, the gun is pulled in tighter to the hip for better concealment.

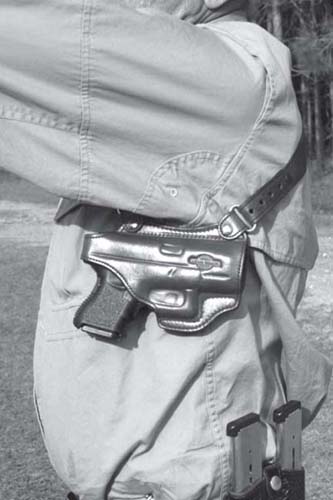

The Yaqui Slide holster, a “skeleton” design popularized by Milt Sparks, is handy in that it fits a number of different barrel length guns with the same frame. Points to note with it, though: 1) If sitting in an armchair and the arm of the chair bumps the gun muzzle, the whole gun can be pushed up and out of the holster. 2) Carbon and dirt on the gun after firing can, while it’s holstered, transfer to the underlying trousers. 3) Sharp-edged sights, or deep Picatinny-style rails on the dust cover (lower front of frame) of some modern military style auto pistols, can snag on the bottom edge of the Yaqui Slide, dangerously stalling the draw. 4) Back in the ’70s, a selling point of this design was that it could stay on the belt with the gun removed, and would often go unrecognized as a holster. This is probably not the case today. The Don Hume version is certainly a best buy for quality vis-à-vis price today, and a key objectionable point to this particular style is removed with models that have thumb-break safety snaps, as offered by Bianchi, Ted Blocker, and others.

With any strong-side hip holster, a 4-inch barrel revolver or 5-inch barrel auto pistol are about the max in overall length that will carry comfortably before the muzzle hits the chair or seat when you sit down, causing some awkwardness and discomfort factor. Larger men, with larger butts and higher beltlines, can perhaps get away with longer handguns.

An outside-the-belt holster is particularly vulnerable to the gun leaning outward because of the butt portion’s weight. Each generation of pistol packers seems to discover that a 3-inch or particularly 4-inch revolver, or a similar size auto, may actually conceal better because the longer barrel bears lightly against hip or leg, pushing the butt in toward the torso to better maintain concealment.

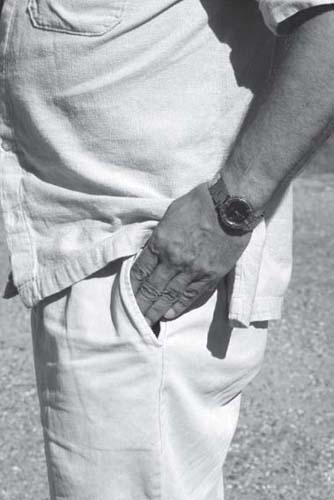

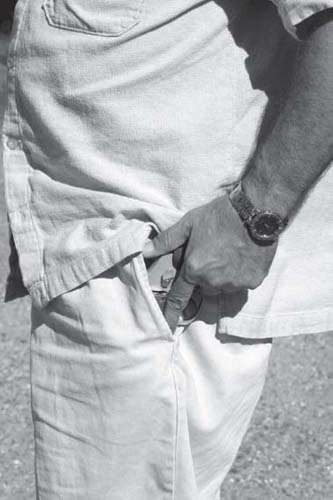

For some, at least in some circumstances, the most viable option is a gun carried ITB, or in the belt, that is, between the belt and the trousers. This allows the user to wear trousers that fit him normally, but the belt pressure pulls the gun in tight as on IWB. However, the IWB advantages of allowing the bottom of the garment to rise higher without revealing the gun, and of breaking up the outline of the holstered gun, are lost. Mitch Rosen’s appropriately titled “Middleman” is one holster designed expressly for this purpose. Another that is perfectly adaptable to this is the Quad Concealment from Elmer MacEvoy’s company Leather Arsenal. Its name comes from the fact that this ingenious and extremely useful rig can be worn outside the belt or between belt and trousers, and can be worn either way ambidextrously.

Author explains why he doesn’t like paddle holsters, but why they can work for some people in some situations. This is one of the best of the breed, by Aker, carrying Ruger GP100 357 Magnum.

Some belt holsters are made with a paddle that goes inside the waistband, securing on the belt and holding the holstered gun outside the pants. The one strong point of this design is convenience: easy on, relatively easy off. I don’t care for them for the following reasons. 1) I’ve seen too many fail to secure, resulting in the holster coming out with the gun. It’s funny at a match or a class, but on the street, it would get you killed. The only thing that would save you would be if your opponent was laughing at you too hard to shoot straight. 2) Since the belt is securing on the paddle rather than the holster itself, guns carried in this fashion tend to lean out away from the body, compromising concealment. 3) The juncture of paddle and holster body is, by nature, weak. I’ve seen even the best brands break here, yielding the holstered gun to the “attacker,” in weapon retention drills. 4) The convenient on/off nature of this holster fosters an “I’ll wear it when I need it” mentality, causing the gun to be left behind and to not be present when, unpredictably, it is needed.

There are many companies that make high quality paddle holsters, but none can get past these inherent weaknesses in the paddle concept. Go to the same maker, turn the page of their catalog, and order one of their holsters that properly secures to a good dress gun belt.

Replaceable belt-clip modules of Kydex IWB holster by Mach 2, the Honorman, “flex” and help conceal this Glock 27 without shifting. Note also “body shield” to keep sweat away from gun, and sharp gun edges away from underlying skin and clothing.

Leather or synthetic? Leather is the classic, and so long as it gets an occasional application of neatsfoot oil or other leather treatment, won’t “squeak.” Cowhide is by far the most common. Horsehide has its fans: it is thinner and proportionally more rigid, but seems to scratch more easily. Sharkskin is expensive, but extremely handsome and very long-lasting and scuff-resistant. It may last you longer than it did the shark. (I often wear sharkskin belts in court. Doesn’t ward the lawyers off or anything, but seems appropriate, especially during some cross-examinations.) Elephant hide? Hellaciously expensive, but certainly tough, and predictably thicker than you probably need. Alligator and snakeskin holsters seem better suited to “show” than “go.” For the most part, cowhide and horsehide are where it’s at.

Rough-out or grain-out? The latter rules with outside-the-waistband carry. The only guy who ever seemed to like rough-side-out belt scabbards was John Wayne, who wore a personally-owned rig of that kind in many of his cowboy movies. It tends to hold sand and dust. The guy who popularized rough-out holster design in concealed carry was the late, great Bruce Nelson, whose Summer Special design was hugely popularized by another departed giant of the industry, Milt Sparks. They found that inside-the-waistband, the rough outer surface had enough friction with clothing to help keep the holster from shifting position; early versions had only one belt attachment loop, and were less stable than the later, improved two-loop Summer Special variations. As a bonus, the smooth grain of the leather was now toward the gun, less likely to trap sand and dust and cause wear on the finish. Some theorized that this also made the draw smoother. However, sweat tended to rapidly migrate through these holsters to the gun, much more so than grain-out IWB holsters that seem to repel perspiration better.

Plastics, particularly Kydex, do not loosen with age like leather, nor do they tend to start out too tight and need a break-in, again a common thing with good leather. Kydex certainly provides more sweat protection to the gun. However, I’m not persuaded that they’re longer lasting. The reason is that their belt attachments are more likely to break. In retention training, with constant struggles for the neutralized guns between two men moving full power, I’ve seen a lot more Kydex and generic plastic holsters break than leather ones. The most secure of the Kydex holsters are the inside-the-belt variations. A genuine tactical problem with Kydex is that it makes a distinctive noise when the gun is drawn or holstered. Sometimes, the concealed handgun carrier wants a surreptitious draw, in which the weapon is slipped out of the holster unnoticed. This is much more difficult with Kydex and requires aching slowness. Score a point for traditional leather in that situation.

However, one advantage of Kydex holsters is that the better ones come with spacers in their belt loops to allow the wearer to adjust the holster to properly fit belts of different widths. For the person switching between casual pants and dress pants, the latter generally mandating narrow belts due to fashion pressure or belt loop size, this can be an advantage. The better Kydex holsters today, such as the Blade-Tech, can ride sufficiently tight to the body for good concealment. They also lend themselves better than leather to carrying a pistol already mounted with flashlight, with reasonable concealment.

There are very few fabric holsters, i.e., ballistic nylon, which will stand up. Most make it difficult to re-holster. For the most part, the “cloth” holsters are at their best as cheap “belt-mounted gun bags” that hold the gun for plinking sessions at the range, and not for daily carry in what might become a dangerous tactical environment.

Blackhawk SERPA is a snatch-resistant, concealable rig that effectively hides this S&W M&P 9mm under a coat. It has been adjusted to desirable forward tilt angle. Finger paddle is easily released by owner’s safely extended trigger finger when draw begins.

“Snatch-resistant” concealment holsters are discussed in the Open Carry chapter. However, they should not be neglected in concealed carry. People who haven’t learned to properly activate retention devices call them “suicide straps,” and prefer open top. They will tell you, “It’s concealed, so you don’t have to worry about someone grabbing it.” Rubbish! Your attacker may know from previous contact with you that you carry a pistol, and even where you carry it. He may have spotted it when scoping you out. Or you might get into a fight and the other guy wraps his arms around your waist for a bear hug or throw and feels the gun, at which time the fight for the pistol is on.

It is good to have at least one “level of security,” that is, one additional thing the suspect has to do to shoot you with your gun in addition to the obvious movement of pulling it out of the holster. An on-safe pistol should count as one level of security. So should a thumb-break safety device. A hidden or “secret” release device may count as two levels. A holster requiring a push in an unusual direction to draw is another level. It’s not a bad idea for the holster to have at least one “level of security.”

A safety strap can also keep the gun in the holster when something other than a hand pulls at it. The gun butt can catch in brush when sliding down a hillside, or on a counter you’re pushed against in a physical fight, or simply come out if you take a tumble butt-over-teakettle. There have been cases of guns falling out of holsters on amusement park rides that put the rushing riders upside-down.

Some, like me, justify the occasional wear of open-top holsters with their extensive experience in handgun retention training. However, even we are likely to have at least a safety strap when out in the brush or performing other strenuous physical activity, or when “open carrying” as police investigators at the station or other environments that increase the likelihood of a gun-snatch attempt.

With practice and proper technique, the difference between open-top and thumb-break in drawing speed is a very thin fraction of a second, a fair price to pay for the added security.

Ayoob designed the LFI Concealment Rig with Ted Blocker, whose namesake company now in other hands still finds it a good seller. Velcro tab on holster (and spare mag carrier, shown) mates with Velcro lining inside the dress gunbelt to secure solidly, and allow wide options to wearer as to height, angle, and location. Pistol is SIG P220 ST 45, with Hogue stocks.

Holsters and belts are as symbiotic as automobiles and tires. We firearms trainers can tell you ad nauseum of students who come in with expensive guns in holsters that should have a Fruit of the Loom label, or may be proof incarnate that you can skin a chicken and tan its hide and make a holster out of it. However, we can also tell you about the students who come in with fine guns in top quality holsters that are hanging off crappy, floppy, narrow little belts whose institutional memory is probably the words, “Attention K-Mart shoppers!”

Even the best holster will, on a poor belt, hang outward from the body. It will shift its position constantly, violating the twin needs of discretion and comfort. There may be so much slop between the belt and the holster’s belt loops, and so much undesirable flexibility in the belt itself, that you can exert the drawing movement for an inch or more and the gun has not begun to leave the holster.

The belt should be fairly stiff, and should be fitted tightly to the holster loops. Often, the easiest way to achieve this is to use a “mated” gun and dress gun belt from the same maker. This also gives a certain pride of ownership. Looks great at an open carry barbecue. Of course, we carry them concealed for the most part, so it’s not really a fashion statement, just a matter of personal satisfaction. I personally don’t care who made the belt and the holster, I care that they go together.

You wouldn’t save up to buy a Volvo or a Mercedes to keep your family safe, and then put on two-ply retread tires. Counterproductive. Ditto a good gun in a crappy holster, or a good gun in a good holster on a crappy belt. I would rather have a $300 police trade-in handgun in a good holster on a good belt, than a $3000 custom pistol in an inappropriate holster on an inappropriate belt. The man with the latter combination will inevitably lose a quick-draw contest to the equally skilled man armed with the former.

For those who don’t care for leather, top-quality nylon dress gun belts such as the defining Wilderness Instructor’s Belt will work fine with casual clothing, and companies like Blackhawk make narrow faux leather belts with matching-loop holsters that will work well in concealment. “Armed and green,” as it were.

A larger gun in a well-selected holster will carry more comfortably and in more discreet concealment than a smaller gun in a poorly-selected holster on an inappropriate belt. Gun, holster, and belt are all part of a system, and if any of those links fail, the whole chain will fail. We’re talking about life-saving emergency rescue equipment here. Failure is unacceptable.

Polymer-framed 9mm Kahr PM9 rides inside and below the waistband, and was designed for cross draw wear.

The cross draw holster – carrying the handgun butt forward, on the hip opposite the dominant hand – seems to be one of those “love it or hate it” issues among experienced pistoleros. There are several handgun sports that actually ban them as safety hazards. But there are also some folks out there who find them perfect for their needs.

Let’s look at the upsides and downsides, and at how to streamline the cross draw concept in ways that may help get past the concerns of the detractors. First, let’s define some terms.

…pistol is drawn across chest, rocking up toward threat …

…and body is ideally positioned for classic Weaver stance.

There are cross draws, and there are cross draws.

Conventional cross draw generally puts the gun all the way over on the opposite hip.

Front cross draw brings the gun to a point between hip and belt buckle, what would be the appendix position for a southpaw. This was the position once favored by IPSC shooters, and by the Illinois State Police back in the Seventies and earlier. It’s also a favorite location for belly-band carry.

This is also a top choice for placing the second single-action revolver required in Cowboy Action shooting.

Fanny packs are often worn in a position that, effectively, puts them in a cross draw location.

Shoulder holsters require a variation of cross draw to bring the handgun into action.

Backup gun rigs attached to body armor are normally worn like vertical shoulder holsters, and therefore call for cross draw techniques and tactics.

The Kramer Confidante, a tee-shirt with built-in gun pockets under the armpits, is designed for wear under a dress shirt or casual shirt. The draw is the same as that from a conventional shoulder holster: a variation of cross draw.

Slider loop in right (forward) slot of Blocker DA-2 hip holster is moved up to orient the holster in a vertical position, ideal for cross-draw carry. Pistol is Glock 17 full-size 9mm with Heinie night sights.

Many of those who choose the cross draw do it because of range of movement issues. Proportionally more female than male cops and CCW civilians carry cross draw than their male counterparts. This is because with a female and a male of the same height, you can expect the woman to have a shorter torso, a higher pelvis, and relatively longer and more limber arms (vis-à-vis the torso) than men. A woman can reach farther under her off-side arm for a shoulder holster, and farther toward her opposite side hip, for these reasons. A cross draw belt holster or shoulder rig that might be literally out of reach of a brawny, broad-shouldered man might be perfectly accessible when worn by his sister.

For women, the cross draw is also an alternative to the problems that come with strong-side hip holsters that have been designed “by men, for men.” The higher hips and more pronounced buttocks of the average woman push the muzzle area of a strong-side holster outward, which concomitantly pushes the butt in toward the body. Because of the higher belt line, a gun “handle” that sits comfortably in the hollow beneath a man’s ribcage can press with excruciating discomfort into a woman’s ribs. When the most popular solution doesn’t work, you need to explore less popular alternatives, and cross draw/shoulder carry is one.

It’s not just a woman’s issue. One of my fellow gun writers has some serious arthritic issues that limit the range of movement of his shoulder. He finds the conventional hip holsters of his youth to be awkward and uncomfortable, and excruciatingly slow. So, he wears his sidearm, usually a 1911 45 auto, cross draw on the opposite hip. Voila: problem solved.

Many bodyguard chauffeurs and others who must constantly be seated, especially at the wheel of an automobile, have come to appreciate across-the-body carry. Many types of car seats inhibit the elbow’s flexion and therefore the reach of the gun hand when going for a strong-side hip scabbard while sitting in a vehicle. A quick reach down across the front of the body is generally faster. In the 1990s, a new breed of holster called the “counter-car-jack” rig made a brief appearance, though it did not seem to catch on. It held the pistol butt down, with the barrel almost horizontal, just to the off-side of midline of the abdomen. Men behind the wheel found it deadly fast. It did, however, have some downsides when one got out of the vehicle.

Hunting advantages. In the game fields, I learned to appreciate a sidearm in a cross draw holster. If it was backup to a long gun, the main gun’s stock was no longer banging into the handgun’s butt all the time. If travel involved ATVs and such, the cross draw seemed more accessible. Shoulder holsters have always been hunting favorites because the outer coat totally protects even big handguns from inclement weather.

I’m not a horseman – the closest I’ve come to hunting with a horse has been driving to the deer woods in a Ford Bronco – but friends who have hunted a lot on horseback tell me the cross draw is much more accessible to a person in the saddle. This is one reason cross draw was so popular among genuine cowboys in the Old West. At the OK Corral shootout, witnesses said Billy Clanton drew his 44-40 Colt Frontier Six-Shooter from a cross draw rig. And he was pretty quick with it. Wyatt Earp had gone into the fight with his own Colt 45 in the capacious, custom-made pocket of his overcoat, with his hand on the gun to start. Yet, when Clanton went to draw, he was so fast from his cross draw scabbard that both Wyatt and Virgil Earp testified later that Billy and Wyatt had fired simultaneously at the opening moment of the gunfight.

Weak hand accessibility. If you need to get to your sidearm with your non-dominant hand, nothing is faster than a gun already holstered on that hand’s side. With a regular cross draw rig on the belt, you simply use the “cavalry draw.” Turn your weak hand so the thumb is pointing to the rear and the metacarpal bones are toward your torso. Grab the pistol and lift. As it starts to clear the holster, point the muzzle down in front of you. The gun will now be upside-down. Rotate your hand to conventional gun orientation as you bring it up on target, and you’ll avoid the common “cavalry draw” mistake of crossing your own body with the gun muzzle.

Is this fast? Well, on the Old West frontier, there were those who carried their guns butt forward and always did a cavalry draw from them! These included the men of the U.S. Cavalry itself, who carried their sabers on their left hips positioned for draw with the presumed-to-be-dominant right hand, and their service revolvers on their right hips in butt-forward flap holsters. The rationale was that if the cavalry trooper needed a weapon in either hand, a revolver was easier to manipulate with the “weak hand” than a saber, and a conventional cross draw would be executed with the weak hand. If the dominant hand reached for the gun, it would do so with the “cavalry draw” described above.

James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok carried a matched pair of Colt Navy 36-caliber revolvers at his waist, butts forward at the points of his hips. He used the cavalry draw exclusively…and he shot his way into history as, some said, the deadliest gunfighter of his time.

…with “hand backward,” conventional grasp is taken. Thumb would pop safety strap if there was one, and then take grasping position as shown…

…gun is pulled straight up along given holster’s natural drawing path, and when barrel or slide area have cleared, gun is rotated butt outward…

…and that way, muzzle never crosses own body as Odin Press dummy of S&W 38 is thrust forward and simultaneously rotated upright …

… and shooter is in a strong firing stance, here using “McMillan/Chapman tilt.”

Compatibility with heavy winter coats. A knee-length overcoat is not the easiest thing to sweep out of the way when you need to suddenly, reactively draw a handgun from a strong-side hip holster. On the other hand, a shoulder or cross draw belt rig is very fast for a right-handed man or a left-handed woman to reach, through the front of the winter coat. All that is required is a coat design that allows one button to be left undone to allow access. (I say right-handed men and left-handed women, because men’s coats button to the left and women’s, to the right.)

One bitterly cold, dark night in the winter of 1970 I was wearing a heavy winter overcoat over a suit as I stepped out of a hotel and made my way through the biting wind to the far, dim corner of the parking lot where I’d had to leave my car. To make a long story short, I “saw the muggers coming,” and unbuttoned both coats so I could get at the Smith & Wesson 38 I was carrying in a Bucheimer scabbard behind my right hip. When they made their move, I made mine, and once my gun came out it was all over. On the way home, I kept thinking about how it might have ended if they’d been more stealthy, and my gun had been buttoned under two coats when I needed to get it quickly. From then on, for a long time after, I carried my gun in a cross draw or shoulder holster in deep winter.

Compatibility with likely “hand start” position. Back in the Seventies, when IPSC (the International Practical Shooting Confederation) first got up and running, the front cross draw was hugely popular. Concealment has never been an issue in IPSC, so a big 45 auto just to port of the belt buckle posed no problems in that regard. Ray Chapman, and many other champions of the day, shot from cross draw. Ray designed the popular Chapman Hi-Ride holster for Bianchi, and the (Ken) Hackathorn Special was a bestseller for Milt Sparks Leather, often worn butt forward.

Why the popularity? Only a few of us seem to remember that back then, one of the most popular start positions at the beginning of a course of fire was with the hands clasped at midline of the body. This put the gun hand just an inch or two above the grip-frame, and gave the user of a front cross draw holster a “running start.” Many of the hip holsters “back in the day” were low slung, even using thigh tie-downs and riding on buscadero-like belts. The also popular “hands up” start position put a high-riding cross draw closer within the shooter’s reach than many of the strong-side rigs. As time went on, it was discovered that moving your Chapman Hi-Ride or your Hack Special to the gun-hand side of the belt buckle made things just as quick, and soon the cross draw was a relic of the past among IPSC’s top contenders.

The Bianchi Cup has always used a hands-up start position. I was there when Ron Lerch won the first, drawing his Colt 45 from a front cross draw, and for the years following when Mickey Fowler ruled the Cup, drawing his custom Government Model from the ISI front cross draw rig he had co-designed with manufacturer Ted Blocker, and named after International Shootists, Inc., the school he founded with training partner Mike Dalton, another ace gunner.

What does any of this have to do with serious pistol packing? Only this: there were times and places where men who knew where their hands would be when they began their draw, and had a lot riding on the outcome, chose the front cross draw position because it was faster to reach.

If you carry a gun for defense, when the day comes, you’ll have a lot bigger stakes on the table than even so prestigious a trophy as the Bianchi Cup. If you can figure out a way to have your hands closer to the gun before trouble starts, in situations where you can’t just haul it out when you smell danger, the cross draw tends to lend itself to early readiness.

Fold your arms at your chest, and let your gun hand slip inside your jacket. Ta-da! Your gun hand is already on your shoulder-holstered pistol, and ready to draw. The two key portions of a draw are access and presentation. Access – getting to the gun and taking a drawing grasp – is the toughest part. Our tests show that starting with the hand on the gun cuts your draw-and-fire time roughly in half. With the cross draw shoulder rig, arms folded across the chest puts you discreetly in position.

Cross draw holster on the belt? The same technique works, simply lowering the folded arms midriff high. Belly-band holster in a front cross draw position? Slide the gun hand in through the opening above the belt that you’ll have if you leave the second button above that belt undone. Take your drawing grasp. Let your free hand fold over that gun hand. Slouch forward a little. You look like a scared guy wringing his hands in a body language “surrender” position…but the belly gun is already in your hand, and you’re ready to draw with the fast, efficient technique that made Chapman, Fowler, and Dalton the famous champions they are.

This, I submit, is a good thing to have on your side of a fight.

Snub revolver like this S&W 340 M&P is ideal for front cross-draw (navel or weak-hand side of abdomen) at belt line with belly-band like this. It’s the author’s favorite, an old Bianchi Ranger that also serves as a hidden money belt.

Cross draw is nowhere near as popular as it used to be. Remember the old TV series Dragnet, where Jack Webb as Joe Friday always had his snub-nose 38 butt forward on the opposite hip? Remember how many other cop shows of the Fifties and even the Sixties had detectives carrying their guns the same way?

That’s almost gone now. I very rarely see cross draw holsters on plainclothes cops anymore, and when I do, they’re usually on the hips of female officers for reasons discussed earlier. Shoulder holsters are somewhat more common, but less so than they once were, even though today’s shoulder rigs are the best and most comfortable that have ever existed.

As far as uniform wear, the cross draw duty holster has been relegated to the police museum. When I was young, cross draw was standard uniform equipment for Metro-Dade officers in Miami, and for the state troopers of Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Michigan and Washington. The last stubborn holdout, the Iowa State Patrol, switched to Safariland security holsters on the strong-side hip just a few years ago for their S&W 4046 Smith & Wesson 40s. They recently replaced those guns with S&W’s new Military & Police autos in the same caliber, but stayed with the strong-side Safarilands. Today, there is not a single major police department in the United States that issues or, to my knowledge, even authorizes cross draw holsters for personnel in uniform.

One of the biggest complaints about the cross draw was that the forward butt made the gun altogether too accessible to an opponent you were facing. Indeed, with the gun all the way over on the opposite hip, it was literally more accessible to a facing man than to the wearer, if they were positioned to each other squarely. Bill Jordan warned against cross draws for just this reason.

The late, great gun expert Dean Grennell was a good friend of mine, and one day he told me that early in his short police career, he equipped himself with a 3 1/2-inch barrel S&W heavy frame 357 Magnum in a cross draw holster that looked just spiffy, and seemed handy to reach when he was at the wheel of the cruiser in the Great Lakes area community he served. Then, one day after lunch, he was washing his hands at the rest room sink and, looking in the mirror, realized just how inviting that forward-projecting gun butt would look to a man standing in front of the uniformed officer. On his next shift of duty, he told me, his Smith & Wesson Magnum was in a strong-side hip holster.

Another big problem, particularly when the gun was worn as a true cross draw all the way over on the opposite hip, was that the draw could sweep the range officer behind the shooter on the range, and would definitely sweep the shooter on the holster side. This is why cross draw has been banned from police combat/PPC competition since its inception in the late 1950s. This is why it has been banned in IDPA (International Defensive Pistol Association) competition since that organization was founded in 1996. I recall visiting the Iowa State Law Enforcement Academy about thirty years ago, back when Iowa state troopers carried S&W Model 13 357 Magnum revolvers in cross draw flap holsters. I learned that when Iowa State Patrol recruits came through the Academy, they were forbidden to use their issue duty holsters, and instead were furnished by the Academy with FBI-style straight-draw scabbards for the strong side hip.

A third concern with the cross draw holster is that it has to ride farther forward on the hip than a strong-side rig. This causes concealment problems. The strong-side concealed carry holster generally is located behind the hip. In cross draw, if the man carrying it is to be able to reach the gun quickly enough to save his life, the butt-forward scabbard has to ride either on the opposite hip, or ahead of it. This makes it much more difficult to conceal when that winter coat is taken off at restaurant, office, or a friend’s home, unless the underlying suit coat or other concealing garment remains closed in the front.

Cross draw as shown is best access to AirLite S&W, worn in hidden pocket behind breast pocket of this Woolrich Elite shirt designed by Ferdinand Coelho. Thumb is on top of hammer area to reduce the combined width profile of the drawing hand and the gun, smoothing and accelerating the draw.

Whatever the concept, my rule is “go toward your strengths and shore up your weaknesses.” The strengths and weaknesses of cross draw carry have already been identified. Let’s look at how to shore up the identified weaknesses if you’ve decided to, at least sometimes, carry the gun opposite your gun hand.

Handgun retention. Take a tip from the Illinois State Police. For the last several years of cross draw carry with their Smith & Wesson Model 39 9mm autos before switching to strong-side holsters in the late 1970s, they wore their flap duty rigs in a front cross draw position, with the gun tilted about 30 degrees toward the dominant hand. Like the Iowa State Patrol and the Michigan State Police, they taught troopers to lift the flap with their nearby weak hand, and draw with the strong hand.

The draw would start from the interview position, with the weak side (which, with cross draw, is the holster side) of their body toward the threat. When this stance is combined with the 30-degree angle of holster rake, the butt is no longer “offered” to the man in front of you. Indeed, it’s your muzzle that’s pointing toward him. This is a much more defensible posture from which to start a struggle for the holstered weapon!

With a cross draw holster on the belt, the Lindell System (Kansas City system) proven for three decades now and created by Jim Lindell, will work. You simply treat the right-handed cross draw holster on your left side as if you were a left-handed person carrying your weapon on your dominant side. The entire repertoire of techniques will work fine.

The Lindell System has never really addressed shoulder holsters. I teach my students a set of shoulder rig retention techniques that were developed by Terry Campbell, late of the Marion County (Ohio) Sheriff’s Department, one of the toughest and best defensive tactics instructors I’ve ever had the privilege of training with. No handgun retention technique (at least, none of the ones that actually work on the street) can be taught in a magazine article or a chapter of a book. But, make no mistake, retention techniques that will protect cross draw and shoulder holsters do in fact exist.

“Sweeping” and Safety Problems. Yes, the cross draw is banned in IDPA, PPC, and most police academies. That said, it’s still allowed to my knowledge in NRA Action Pistol Shooting (including the Bianchi Cup), IPSC, and of course, cowboy action matches. The requirement that makes it safe in those venues is the one you want to use religiously for your own practice “for the street.”

Always remember: “If it’s not safe to practice on the range, you’ll never build enough repetitions to make it work reflexively and safely in the real world.”

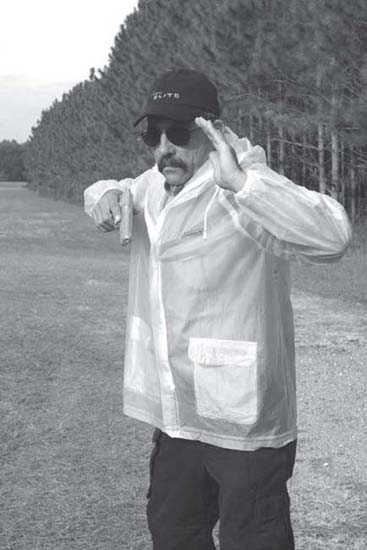

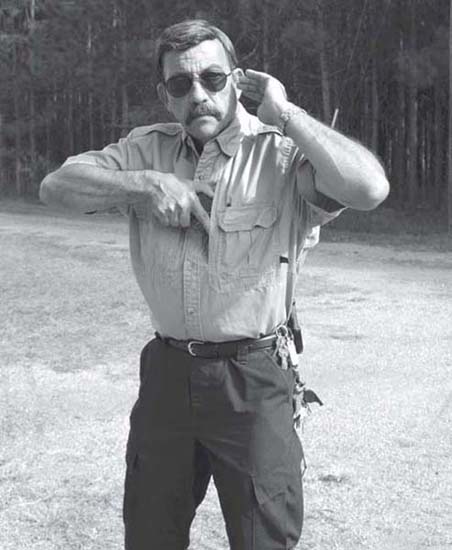

To make the across-the-body draw safe and efficient, drill in the following steps. They’ll work with conventional cross draw, front cross draw, belly-band, fanny pack, shoulder holster, et. al.

Step one: Take a step back with the leg on your gun hand side, turning the holster side toward the threat.

Step two: Drop the gun hand straight down to the grip-frame. As you do so, raise your non-dominant hand as shown in photos, into a blocking position. This will keep your gun arm clear of your muzzle’s path.

Step three: As you draw, bring the pistol back across your body toward your strong hand side until the muzzle comes up and into the target. There should be no “sweep” laterally: the muzzle should come right up out of the holster and toward the threat.

Step four: Punch the gun toward the target.

Step five (Optional): If there is time for a two-hand hold, bring the support hand down and forward, coming in on the gun from above and behind so your support hand is never swept by the muzzle. Because of the torso angle, this type of draw lends itself very well to the classic Weaver stance, or the modified Weaver stance popularized by Ray Chapman. To go to Isosceles if that’s your preference will require an additional movement, a turn of the hips that squares the target to the threat while leaving the non-dominant side’s leg forward and the dominant side’s leg to the rear, leaving your feet still in a boxer’s stance.

Only the smallest and shortest of combat autos, such as this 9mm Kahr MK9, work well in front cross draw inside belly-band. This rig is from Action Direct.

The cross draw holster is not at its height of popularity right now. That doesn’t mean that there aren’t some people for whom it’s the best choice. Nor does it mean that each and every one of us might not find some special purpose that is best fulfilled by some sort of across-the-body carry.

It’s like so many other things. It’s safe if you do it correctly, and may even be more efficient. But when any of us go to a new technique – or resurrect an old one, like this – we have the responsibility of making sure we’re doing it correctly, and making the right choice for the right reason.

Bianchi X15 shoulder rig that must be a quarter century old, but still works perfectly.

The driving rain sweeps the night streets and sidewalks of the city, making them look like glistening pools of ink, streetlights and automobile headlamps sending swords of light across their oily surfaces. You pull up the collar of your trench coat, and tug the brim of your dripping fedora a little lower down over your eyes. You reach inside the coat to feel the reassuring solidity of the gun in your shoulder holster…

Ah, yes, the shoulder holster is a part of whole noir scene, in movies and novels alike. Frank Sinatra carried a Colt pocket model in a Heiser-type shoulder holster in Suddenly, and one biographer says he wore the identical combination, loaded, under his custom tux and suit coats, in a time when most carry permits were discretionary and most movie stars could get them. Robert Stack as Eliot Ness carried a Colt Official Police 4-inch in a butt-up spring clip shoulder rig of the Heiser style, as did all his men on the TV show. Playing the same role in the movie The Untouchables, Kevin Costner wore a Colt 1911 auto in a shoulder rig. As a matter of fact, the real Eliot Ness did wear a shoulder holster, and a Colt. However, Ness’ Colt seems to have been an early 38 Detective Special with a 2-inch barrel.

On the printed page, the mid-20th century saw Mickey Spillane’s classic “hard-boiled private eye,” Mike Hammer, carrying a 45 automatic in a shoulder rig. In one book – I want to say “Vengeance Is Mine,” but I’m working from memory here – Hammer replaces a lost 45 with a military surplus Colt 1911 bought from a New York City gun dealer. In the last of the novels, The Black Alley, Hammer’s shoulder holster carries an updated, commercial Colt 45 auto, the Combat Commander. A popular paperback private eye of the 1960s, Shell Scott, was armed by author Richard S. Prather with a snub-nose Colt Detective Special 38 in a “clamshell shoulder holster,” which I always pictured as a Berns-Martin Lightning.

The glamorous image of the shoulder holster went beyond private investigators. One of today’s best-selling novelists is Laurell K. Hamilton, who’s most popular character is “Anita Blake, Vampire Hunter.” Set in an alternate reality in which vampires and assorted were-beasts are out of the closet, politically active, and legally protected, they can only be slain if a judge signs a warrant and dispatches a Licensed Vampire Hunter like the heroine. A petite female, Anita Blake was armed by her creator with a Browning Hi-Power and a Star StarFire, both loaded with all-silver 9mm hollowpoints, and one carried in a shoulder holster with the other backing it up in an inside-the-waistband holster.

What character in modern adventure fiction could be more famous than James Bond, Agent 007? The late Ian Fleming equipped him with a Beretta 25 in a chamois shoulder holster in the early novels. (This ignored the fact that chamois would probably hold moisture and rust the gun it contained, which is probably why you never see anyone in the holster industry actually making the things out of chamois.) In Doctor No, Fleming summoned the assistance of leading British handgun authority Geoffrey Boothroyd, who more or less played a cameo as himself in the novel, but apparently Fleming didn’t keep good notes of Boothroyd’s advice. 007 wound up with a 32-caliber Walther PPK in a Berns-Martin Triple Draw holster, which could be worn as either a belt or shoulder rig. Problem was, this design secured on the cylinder and was available for revolvers only, not autoloaders such as the Walther.

When the Zodiac Killer stalked San Francisco, the crack SFPD investigator who hunted him was the famed Dave Toschi. Photos of the period show Toschi wearing a short-barrel revolver in a shoulder rig. Toschi is said to be the real-life model for the character Steve McQueen played in Bullitt, and in that move McQueen wore a 2 1/2-inch barrel Colt Diamondback 38 Special in an upside-down Safariland shoulder holster.

…gun hand draws, NOT down and out, but STRAIGHT ACROSS CHEST, which will clear support arm now and also …

…more quickly get the muzzle on the threat …

…and smoothly flow into a classic Weaver stance.

Why so much “reel life” before getting to “real life” use of shoulder holsters? The reason is, no holster choice has been so much influenced by the entertainment media – print, film, and television – as the shoulder rig. In their classic non-fiction text on holsters, Blue Steel and Gunleather, John Bianchi and Richard Nichols said, “Perhaps no other category of holsters has more nostalgic appeal. Although such holsters were first used many decades earlier, the cops-and-robbers movies of the Thirties, followed by subsequent prohibition movies of the Forties and Fifties brought shoulder holsters to the attention of the public. The old gangster-versus-police films featuring James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson, and Humphrey Bogart (who were alternately cast as good and bad guys), were liberally sprinkled with a wide variety of shoulder holsters. Wardrobe and property departments made liberal use of the dramatic impact of these harness rigs.”

The fact is, though, that art was imitating life, as it should have been. Nichols and Bianchi were correct to note that the shoulder holster had long preceded cinema. Dr. John “Doc” Holliday was known to frequently wear one, and as noted, so did the real Eliot Ness. Shoulder rigs were seen on the other side of the law in the Roaring Twenties and the Depression years, as well. Baby Face Nelson was partial to shoulder rigs. So was John Dillinger, who had been observed wearing a twin shoulder rig with a pair of Colt 45 automatics by the nervous folks who dropped a dime on him at the Little Bohemia Lodge and set the stage for what was then the FBI’s most humiliating debacle. (Dillinger didn’t wear shoulder holsters or 45s when they weren’t suitable for his lifestyle, though. On the hot summer night when he was killed outside the Biograph Theater in Chicago, he was coatless, and carrying a Colt 380 automatic in his pants pocket, and a spare magazine of UMC 380 ball ammo in another pocket.)

This horizontal shoulder rig, the Stylemaster by Mitch Rosen, conceals even on an average size torso with the “baby Glock.”

Shoulder rigs were more popular in the time of Eliot Ness than now. Part of that came from most folks not yet having figured out that good gun belts were necessary for hip holsters, and part of it was that hip holsters hadn’t yet come anywhere close to today’s state of the art.

Nowadays, cops and armed citizens alike vastly prefer belt carry to shoulder carry, but that does not by any means make the shoulder holster obsolete for gun concealment. There are several situations where they come in handy.

Female users seem proportionally much happier with shoulder rigs, particularly detectives who wear guns constantly and daily. Many of the factors on the male body that make the strong-side hip holster a guy’s favorite, are not present on his sister, even if she’s the same height. The female torso is proportionally shorter than the male’s, and her pelvis proportionally much higher and usually a lot more flared. The gun butt that rests just perfectly below the ribcage behind the brother’s hip digs painfully into his sister’s floating ribs, due to the higher pelvis and shorter torso. Moreover, the flare of her hip pushes the bottom of the holster outward at the barrel end, which concomitantly forces the butt end uncomfortably into her side. As if this is not enough, the weapon sits so high that she practically has to disarticulate her shoulder joint to perform a proper hip draw.

If the hip holster is a “by males, for males” design that is ideal for most men and difficult for many or even most women, the shoulder holster turns out to be the exact opposite. A great many men, particularly big guys, have tried shoulder rigs and found them mercilessly uncomfortable, while women do not have the same problems with them as their brothers.

Once again, it’s a case of vive la difference. A woman’s torso tends to be narrower through the chest and rib cage area than that of a man the same height, and her arms will be proportionally longer and usually, more limber. This makes certain angles of shoulder holster carry – notably the 45-degree muzzle up/butt down position, and especially the muzzle straight up position – difficult for the male to reach in terms of proper grasp and draw. This becomes increasingly worse as the male gets more broad-shouldered (forcing his arm to reach farther) and more broad-chested (also impeding his reach in that direction.)

Try this simple test. Put together a man and a woman of roughly the same height, and ask each to raise their left arm and reach their right arm across the left armpit area where the shoulder holster would hang. See how far they can reach. Most males will run out of range of movement with the tip of their longest finger somewhere in the armpit area. Typically, though, the female will be able to reach around so far that she can pat herself on the shoulder blade, and I’ve seen a very few women so slender and flexible, their middle finger could touch their spine.

In other words, she can reach much farther in the direction a shoulder holster draw requires, than he can.

There are other reasons so many women prefer shoulder rigs. Only the most casual female wardrobe will allow the sort of quality dress gunbelt that men can wear even with business suits. The self-suspensory nature of the shoulder holster solves that problem nicely. Hanging a spare magazine or two under the off-side arm from a flat, soft, well-designed piece of leather or synthetic seems to be more comfortable and less protuberant than hanging it on the belt. And, if she has a narrow waist, space there is at a premium, but there’s a vacant place to hang gear right there under the armpit.

Upside-down shoulder holsters (muzzle up, butt down) work best with smaller, lighter guns, author has found. This is the old Bianchi 209, carrying an Airweight S&W J-frame 38 Special with Eagle “secret service” grips.

Some occupational requirements force the person wearing the gun to be constantly seated. A teller’s cage. An office or cubicle. Behind a steering wheel. A wheelchair. Many practitioners have found a comfortable shoulder rig to work well in these applications. However, the optimum word is “comfortable.”

You can achieve the same goals with a cross draw belt holster, but the shoulder rig has some advantages. Depending which side of the seat you’re on, the armed driver or bodyguard/chauffeur may find seat belts getting in the way of the cross draw holster. A “shoulder system” with spare ammo suspended beneath the armpit opposite the holster may also give faster access to spare magazines than would a belt pouch for a seated person.

These “reach” factors may significantly favor the person who is constantly planted in other types of seats. An armchair’s arms, and those of a wheelchair, can catch a hip holster on either side of the body. The shoulder rig will literally be “above all that.”

There can be a downside, however, and again it goes to comfort factor. “Concealed means concealed,” and in an automobile, that means a covering garment must constantly be worn. The long-haul driver with a handgun holstered on either side of his belt can generally take his coat off, and it will probably go unnoticed by anyone not in the vehicle with him, or not leaning into the vehicle and peering in. Not so the shoulder rig. Failure to realize this led to the fortunate arrest of American terrorist Timothy McVeigh, who was stopped by a lawman who spotted McVeigh driving while wearing a Glock 45 auto in an uncovered shoulder holster. The policeman drew his own Glock and arrested McVeigh at gunpoint. Apparently more comfortable blowing up children with explosives from a safe distance than he was facing armed good guys, McVeigh meekly surrendered.

The shoulder holster works well for “drivers” of conveyances other than automobiles. Most of the police pilots I’ve flown with – and virtually all of the police helicopter pilots – wore shoulder holsters.

That goes for farm vehicles such as tractors, as well. Don’t forget, part of a day’s labor on a working farm is getting under the tractor or the machinery to fix it. If a snake slithers along at that point, it might be difficult to get at your hip. No one has a better perspective on this than my old friend Frank James. A well-recognized authority on firearms and the gun industry, Frank also owns a successful working farm. In fact, his good-natured nickname among friends is “Farmer Frank.” One of those friends is noted weapons expert Rich Grassi. In the 2008 edition of Harris Publications’ Concealed Carry annual, Rich asked half a dozen of us what we carried on our own time and why, and called the article “Carry Guns of the Professionals.” Frank James had the following to say:

“Unlike many in the gun-writing field, I am an advocate of the shoulder holster because in my experience, waist or hip-mounted holsters are poor choices during operation and/or the repair of farm machinery.

“Throughout the harvest, I usually rely on an S&W M657 41 Magnum with a custom 4-inch barrel and a Walt Rauch-designed gold bead front sight. This revolver is routinely carried in an A.E. Nelson Model 58 shoulder holster with the old-style Al Goerg shoulder harness. On certain occasions I will substitute a custom-built Heinie Springfield Armory 10mm 1911 pistol for the S&W M657. This is my second Heinie 10mm 1911 pistol, since I wore the first one (built on a Colt Delta Elite) out, but I’ve also worn out three different S&W 41 Magnum revolvers. The holster used with the 1911 is the Galco Miami Classic, but I adjust the holster to a highly angled rake with the muzzle up and the butt down because that makes the whole thing less prone to snagging on hoses, levers, and other stuff,” Frank concludes.

Note orientation of muzzle of upside-down shoulder holster: subclavian artery and other vital parts are in line of the muzzle. With these, author recommends draw begin with this Kerry Najiola block, elbow high, clearing brachial artery out of the way and giving head good protection against physical blows and contact weapons. Draw is otherwise the same as with horizontal shoulder holster.

The man who invented both the concept and the term “shoulder system” is generally conceded to be Richard Gallagher, with his early Jackass Shoulder System line that became the cornerstone of his later Galco gunleather empire. Here we had a comfortable figure-eight harness that did not put direct pressure on the neck. Under the armpit opposite the dominant hand swung the holster, which could be adjusted from horizontal draw if the gun was short enough to conceal that way, to 45 degrees or more angle of muzzle up/butt down. And, on the opposite side, there were pouches for ammunition – loose revolver cartridges, auto pistol magazines, even speedloaders later – and handcuffs.

This absolutely captivated the type of plainclothes officer who is uncomfortable carrying a gun all day. By pulling open the desk drawer when an emergency call came in, this practitioner could don the shoulder rig as easily as throwing on a coat, and voila! Gun, ammo, and cuffs were suddenly onboard and ready to go in one smooth swoop.

There are those of us who don’t care for this approach, since we know that one might be away from that desk drawer, or wherever the shoulder rig is stored, when the call to arms comes. We prefer to put our gear on in the morning and take it off when we are certain we will no longer need it. However, we have to realize that not everyone who carries a gun on the side of the Good Guys n’ Gals shares this attitude. A quickly donned set of gun-and-gear beats hell out of no gun and gear, and that’s why, even if this had been Richard Gallagher’s only design, it would have earned him a place in the history of great holster designers.

Another useful purpose for the shoulder system is the bedside “roll-out kit.” Only the most paranoid (or those at genuinely red alert level of risk) sleep with their guns on. When the burglar alarm goes off or the glass breaks, a shoulder rig right by the bed allows the awakened home defender to do exactly what that lax-about-carrying cop does with his shoulder system. In a trice, with little more than a shrug of the shoulders, the necessary gear is strapped to him even if he doesn’t have time to fully get dressed. A small, powerful flashlight clipped to the shoulder strap, perhaps even a pouch attached for a cell phone, and the defender is equipped to “roll out” and handle necessary defensive task.

Many men have difficulty reaching far enough across their chest to get good drawing grasp on upside-down shoulder holsters. Here’s Ayoob’s suggestion: snag it with your middle finger…

…flip it forward into drawing grasp, and then complete the draw. This is Blackhawk dummy version of S&W Centennial revolver, in Bianchi 209 shoulder rig.

One reason I keep shoulder holsters in my personal wardrobe is that over the years, I’ve occasionally “thrown my back out.” It always seemed to be something in the lumbar region. There are also hip injuries that can make anything heavy worn on a belt (or even a belt itself) intolerable. In situations like that, a shoulder holster can be a Godsend.

Indulge me in a little personal remembrance. In the early 1990s, I managed to throw my lower back out big time. The doc told me in no uncertain terms that I was not to have any weight on my belt. If I was going to do police work, he said, it would have to be administrative or investigative, so I wouldn’t need to be in uniform, because he had treated a lot of police back patients and knew how heavy the Sam Browne duty belt was.

“No problem,” I told him. “I’m sure my chief will let me do plainclothes for a while. I’ll just wear a shoulder holster.”

He looked at me, dead-level serious, and answered, “Make sure you wear one on each side.”

There was a long moment of silence. I ventured uncertainly, “Uh, you’re kidding me, right?”

“Not at all,” snapped the doc. “Think about it. Your lower back is trying to heal. Your lower back supports your upper body. If weight is off-center on one side of your upper body, your lower back isn’t going to heal, is it?”

I went home to the holster room and cobbled together a double rig for a pair of Smith & Wesson revolvers. The harness and the left-hand holster were from an early Bill Rogers design, and the right-hand holster was from an old Jackass Shoulder System. It was exactly balanced. The short-barrel K-frames were adjusted to horizontal carry, held securely in place by thumb-snaps, and were very quick to get at. And, sure enough, my lower back sighed in relief.

And I felt like Sonny Crockett’s older, stranger brother.

Sonny Crockett was the character played by actor Don Johnson on the then-popular TV series, Miami Vice. Show creator Michael Mann was big into both cutting edge guns and authenticity. He had the Crockett character carry a little Detonics 45 in a black nylon ankle holster for backup, and as primary, a Smith & Wesson Model 645 45 auto or, for much of the series, an oh-so-trendy Bren Ten 10mm auto. Both were big, heavy pistols, so the Crockett character wore whichever he carried in a given season in a shoulder system. The shoulder rig du jour was either a Ted Blocker or a Galco, again depending on the season of production.

I spent a little time with a postal scale, and determined that a Colt Lightweight Commander pistol loaded with 185-grain jacketed hollowpoints exactly balanced out with two spare loaded magazines, a pair of handcuffs (I forget which set, but they may have been the old S&W Airweights made of aluminum like the Commander’s frame), and finally a Spyderco Police Model knife clipped onto the harness on the opposite side. That was the rig that carried me through to recovery, at which time I went back to my old, familiar hip holsters and belt-mounted magazine pouch.

The shoulder holster has much to recommend it in very cold weather. By leaving one button undone, the hand can knife through the opening in the coat to grasp the pistol, even when bundled up against sub-zero weather. Living more than half a century in New Hampshire, which can become a frozen wasteland in winter, I found that when I took my overcoat off in an office or restaurant, the sport coat or suit coat beneath it generally stayed on, and the thermostat in the given place was generally adjusted to allow for that.

Others had noticed it long before I came along. Hunters in particular learned to appreciate shoulder holsters. Part of that was that big-game hunting season generally falls in the cooler months, and part of it was that the outer garment made a perfect protector of the shoulder-holstered handgun from inclement weather in the great outdoors. When the handgun is backup to the rifle or shotgun, it also keeps the stock of the long gun from getting scratched against the handgun on the same-side hip, or the adjustable sights on the holstered 44 Magnum from being inadvertently knocked out of alignment by the butt of a long gun. Pioneering handgun hunter Al Georg, in the 1950s, did a great deal to popularize the shoulder rig among handgun hunters.

The hunter’s concealed handgun can protect him from more than dangerous wild game. The following account appears in the book Street Stoppers by Evan Marshall and Ed Sanow, published by Paladin Press.

“While hunting bear in the northwestern United States, he carried a S&W Model 57 41 Magnum with an 8 3/8-inch barrel in a shoulder holster as backup, loaded with Winchester 170-grain JHPs. He and his hunting partner had spent a frustrating day without even seeing a bear. They had returned their rifles and related equipment to their motel room before going out to dinner.

“They were returning to their car when they were approached by a shabbily dressed individual who asked for money. The hunter gave him $5, but the man made a sarcastic remark about the bigger bills in his wallet. Ignoring him, the hunter turned toward his car when he was struck in the back. Thinking that the panhandler had hit him with his fist, he turned around to see the man holding a large knife in his hand. Realizing that he had been stabbed, he pulled the revolver from the shoulder holster and shot him twice.”