21. Orient Excess

‘How do you feel about playing in China?’

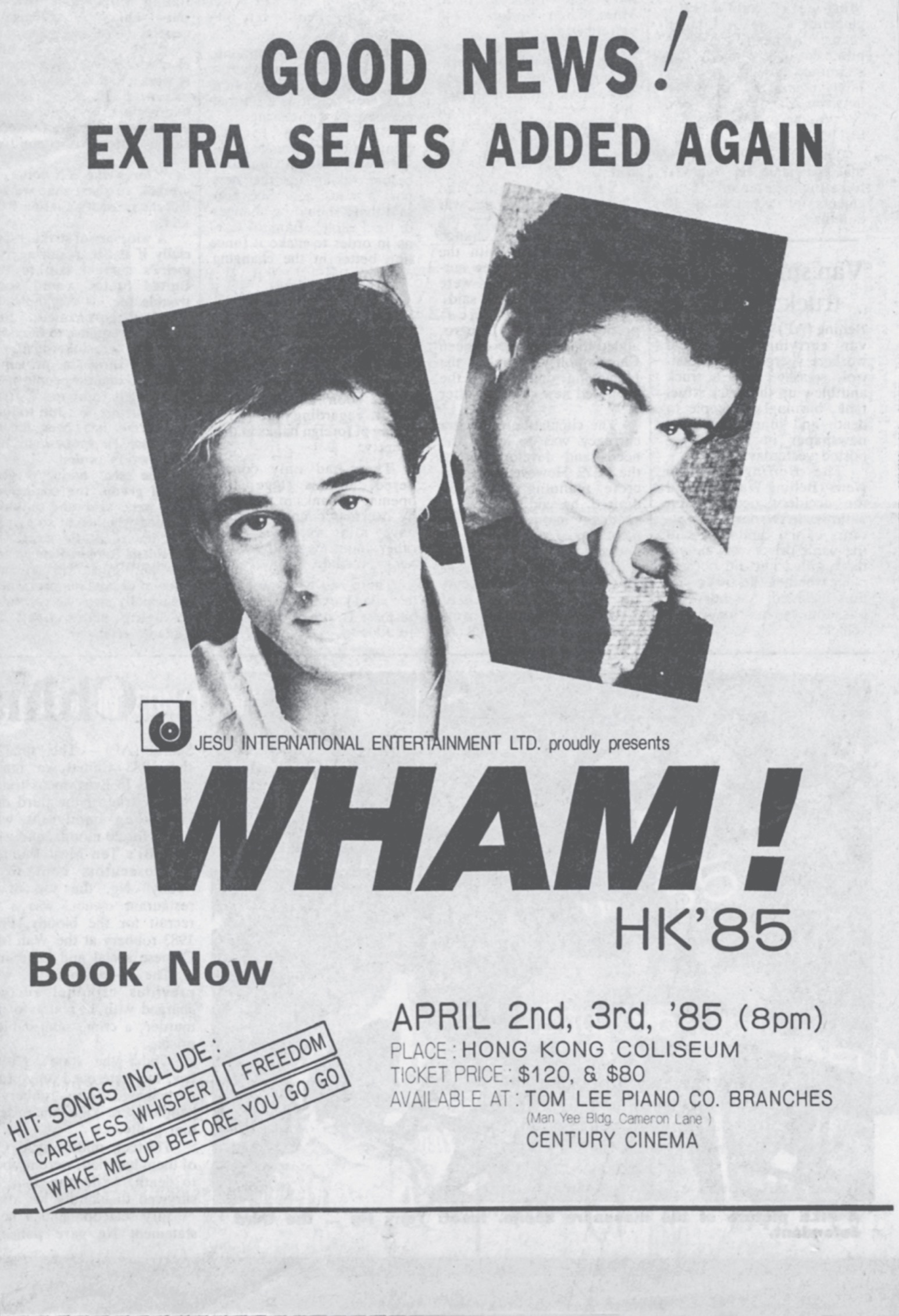

When Simon and Jazz first mooted the idea of travelling to what was then considered an unfriendly communist state, neither George nor I were too taken by it. We had barely made our first steps into America, after playing just six theatre shows, so performing in somewhere as off the wall as China felt genuinely crackers, but there was method behind the madness. Simon understood the power of a grand attention-grabbing gesture, and he also knew that George’s reluctance to embark on an extensive tour of the States was going to severely impair our ability to break the US market big time and capitalise on the success of Make It Big. Denied the exposure that a major nationwide tour, with all its attendant local publicity, would generate, Simon knew he had to come up with something that would give us more bang for our buck. He needed to create a little hype. And in his own inimitable way, Simon came to the conclusion that the best way to do that was to introduce Wham!’s effervescent brand of pop to the Middle Kingdom. By becoming the first Western band to perform there, we would garner headlines in America and around the world. Or so went the theory.

I still felt China was a crackpot idea! I knew the trip was going to cost us a fortune and I wasn’t entirely convinced that the two gigs being arranged by Simon in Peking and Canton (this was long before Westerners took to calling them Beijing and Guangzhou) would actually attract the global attention he thought it would. China was so far off the radar that Simon’s plan seemed to be based on faith more than evidence. It was hit and hope.

But Simon remained convinced and had been shuttling to and from China as we’d recorded Make It Big, striking all sorts of deals with various political figures to ensure our performances could go ahead. Once he had played his trump card and explained to George that his master plan would spare us from the need to crisscross America touring and fulfilling endless radio and TV promo obligations, we agreed to go along with it. Simon’s scheme also made a similarly gruelling European tour surplus to requirements. Instead, we were going to strike out into uncharted territory.

Wham! was about to make pop history.

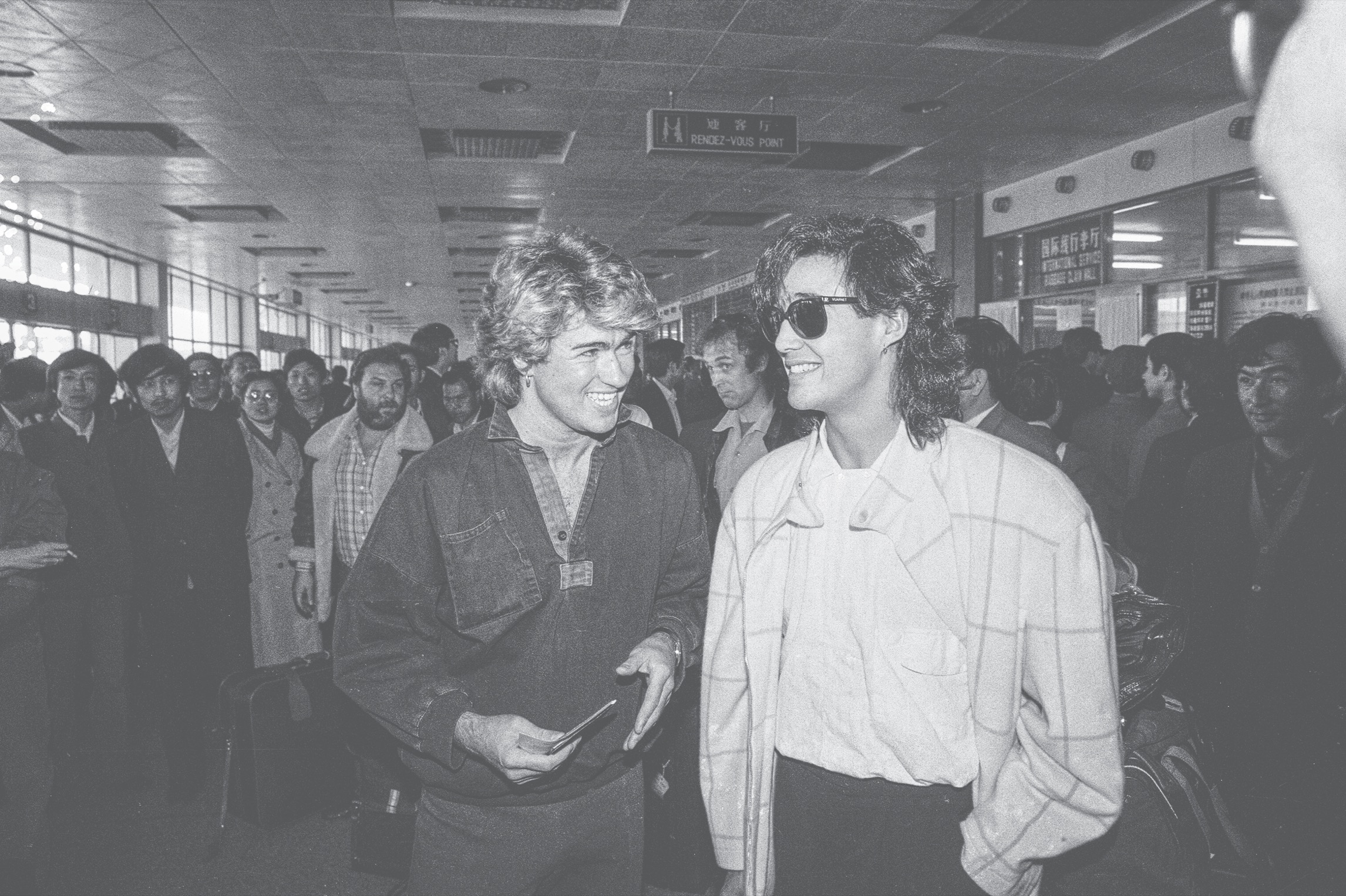

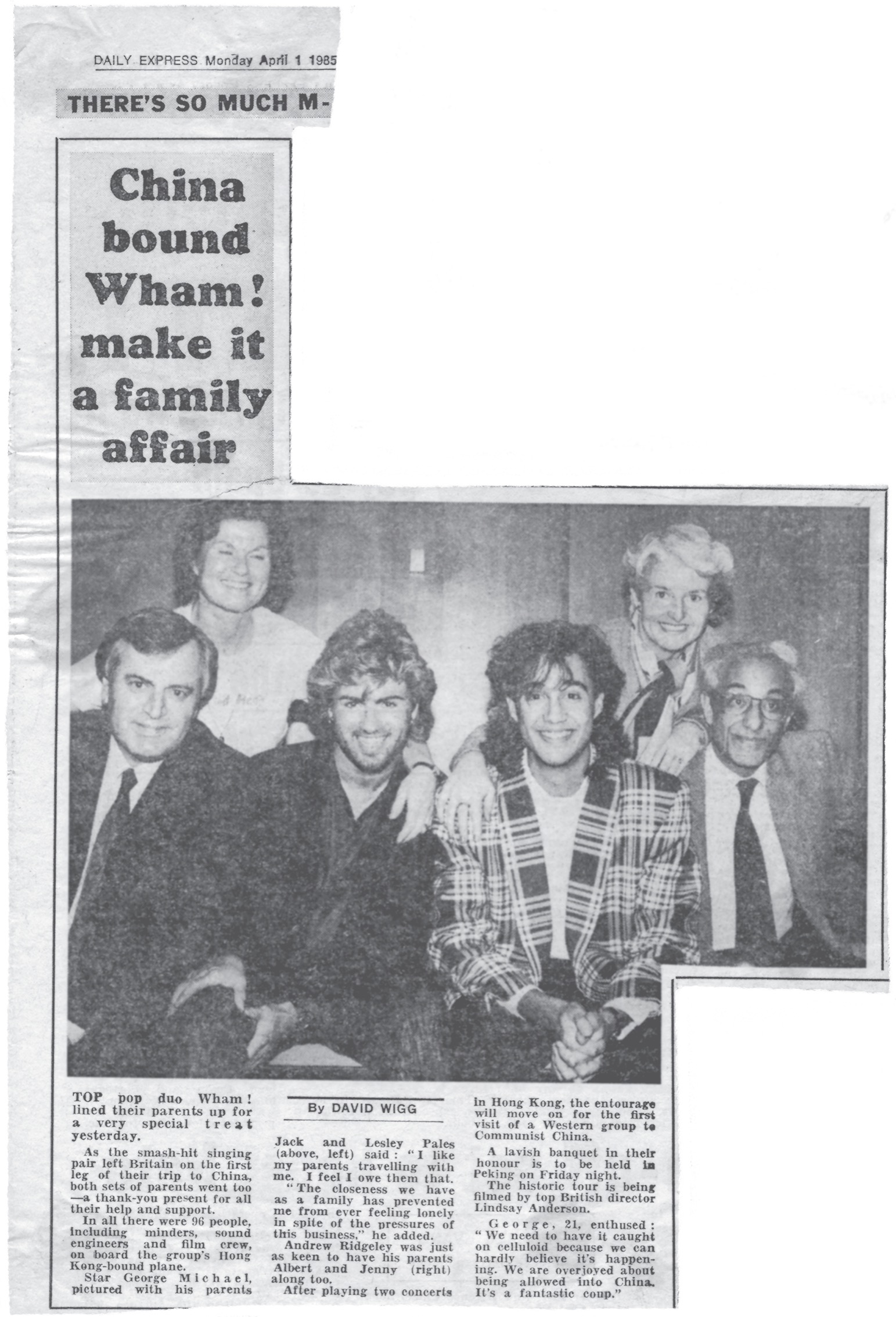

We flew into Peking in April 1985. In real life, the country seemed to exist just as it had in my imagination. Streets echoed with the sound of tinkling bells as hundreds and hundreds of cyclists whizzed along. Nearly all of them were dressed in the drab Mao suit of grey tunic and matching trousers. It was supposed to be a symbol of Chinese unity, but I don’t think they had too much choice in the matter. Meanwhile, only one Western-style hotel existed in the city and so we were installed there. Although comparatively modern, its fixtures and fittings were basic compared to what we had become used to at home and abroad. For some reason everything smelled of chemicals. But it was people’s reaction to us that struck me most. It’s easy to forget now just how closed and insular China was at the time. Everyone we encountered seemed to be wary of us.

We soon came to feel a bit trapped by it. We were set to stay in China for ten days but had been prohibited from exploring the city away from the official tours being arranged for us. Minders followed us everywhere. We travelled to the Great Wall of China and visited temples; we were escorted to a local food market as part of a cultural excursion where we played ‘Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go’ on a tape deck to a crowd of bemused local workers, most of them in their sixties and seventies. At grand banquets we even ate wildly exotic meats and vegetables, most of them unfamiliar to us. And an atmosphere of cautious curiosity trailed us everywhere we went. It was all very different to the screaming girls and autograph-chasers that mobbed us everywhere else. Instead I shook hands with government ministers and bowed my head deferentially to China’s great and good. In one surreal episode, I found myself addressing a room full of dignitaries at a fancy dinner in an ornate city hall. I did my best to establish some kind of connection.

‘My partner George and I both feel that the nature of our performance is in many ways similar to some facets of Chinese theatre,’ I said. The two of us had been bickering about the speech only moments earlier, both unsure of what tone to strike in a culture that was entirely alien to us. I wasn’t even sure if opening with ‘Ladies and gentlemen . . .’ would be appropriate. Were there going to be any women in attendance? I didn’t know. But whatever we did, and wherever we went, there was the constant sense our actions were being scrutinised, the Chinese authorities fearing their youth might be overly influenced by two Western pop stars with flamboyant hairstyles and a wardrobe of Phillips Tailor’s tartan suits. We were only playing China in the hope it might save us from touring America. The Chinese Communist Party, meanwhile, appeared to be unsure about the wisdom of having agreed to our visit. There was an unusual strain to everything we did.

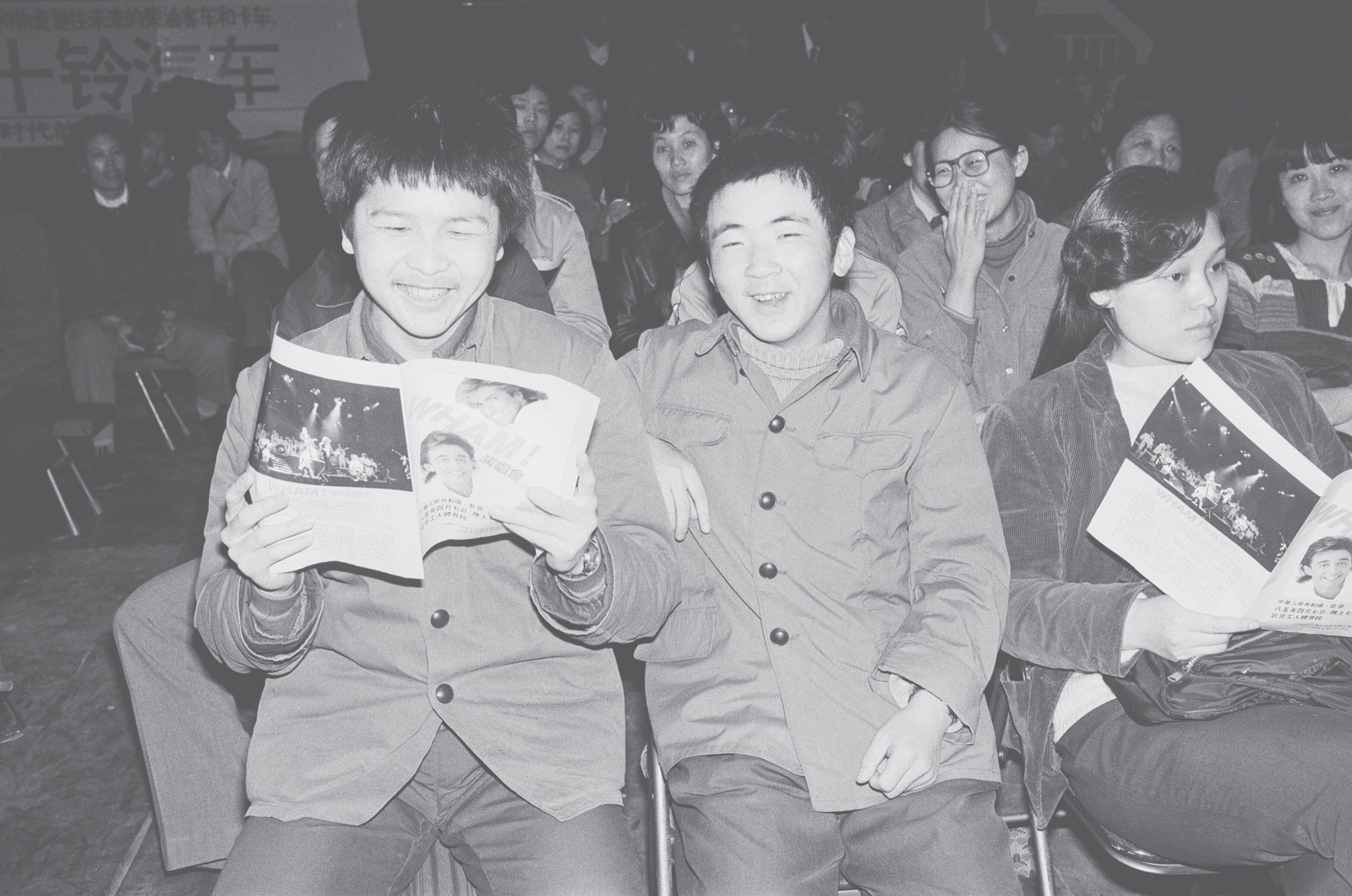

This awkwardness was never more evident than when we played our first gig at the People’s Gymnasium in Peking, a vast indoor space capable of seating fifteen thousand people. It had previously been best known outside China for hosting the World Table Tennis Championships in 1961. Before we walked onstage, ticket holders were warned not to celebrate our arrival too exuberantly and I later heard that leaflets had been issued to fans before the show carrying strict instructions about how to behave. The Minister of Culture was even encouraging Chinese kids to ‘watch, but not learn’ from our performance. After taking to the stage I noticed lines of police officers, all facing the audience in an intimidating wall of authority. Each new Wham! fan had been a given free cassette of our songs with their ticket. On one side our songs appeared in their original form. On the reverse our opening act, a local Chinese singer called Cheng Fangyuan, had covered tracks like ‘Club Tropicana’ and ‘Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go’ in Chinese. The lyrics had been rewritten with a distinctively communist flavour.

Wake me up before you go-go,

Compete with the sky to go high-high.

Wake me up before you go-go,

Men fight to be first to reach the peak.

Wake me up before you go-go,

Women are on the same journey and will not fall behind.

Quite. I couldn’t have put it better myself.

As we started to play, it was impossible not to feel similarly off kilter. Christ, this isn’t going to be the usual show . . . I thought as the synth pop of ‘Bad Boys’ played incongruously over the heads of hundreds of stiff-backed cops, all facing away from the stage. There were small pockets of dancing. Foreign students, lucky not to live under the same restrictive rules as everyone else in the vast room, were allowed to enjoy themselves, but when one local man joined in the fun, several officers descended upon him and warned him to stay in his seat. When he then kicked up a fuss, he was forcefully dragged away. Pepsi and Shirlie were both really upset by the incident and it was hard not to imagine that he had been given a terrible beating or, worse, sentenced to a period of hard labour at some god-awful detention camp. But despite the uneasy atmosphere, the gig would prove to be something of a watershed. Years later, once China had become a more open and welcoming state, stories about the impact we’d made on China’s younger generations began to emerge. Kids had apparently sought out jeans and denim jackets. Others tried to track down more Western music, which opened the doors for other British and American bands to perform there, with the Police following in our footfalls shortly afterwards.

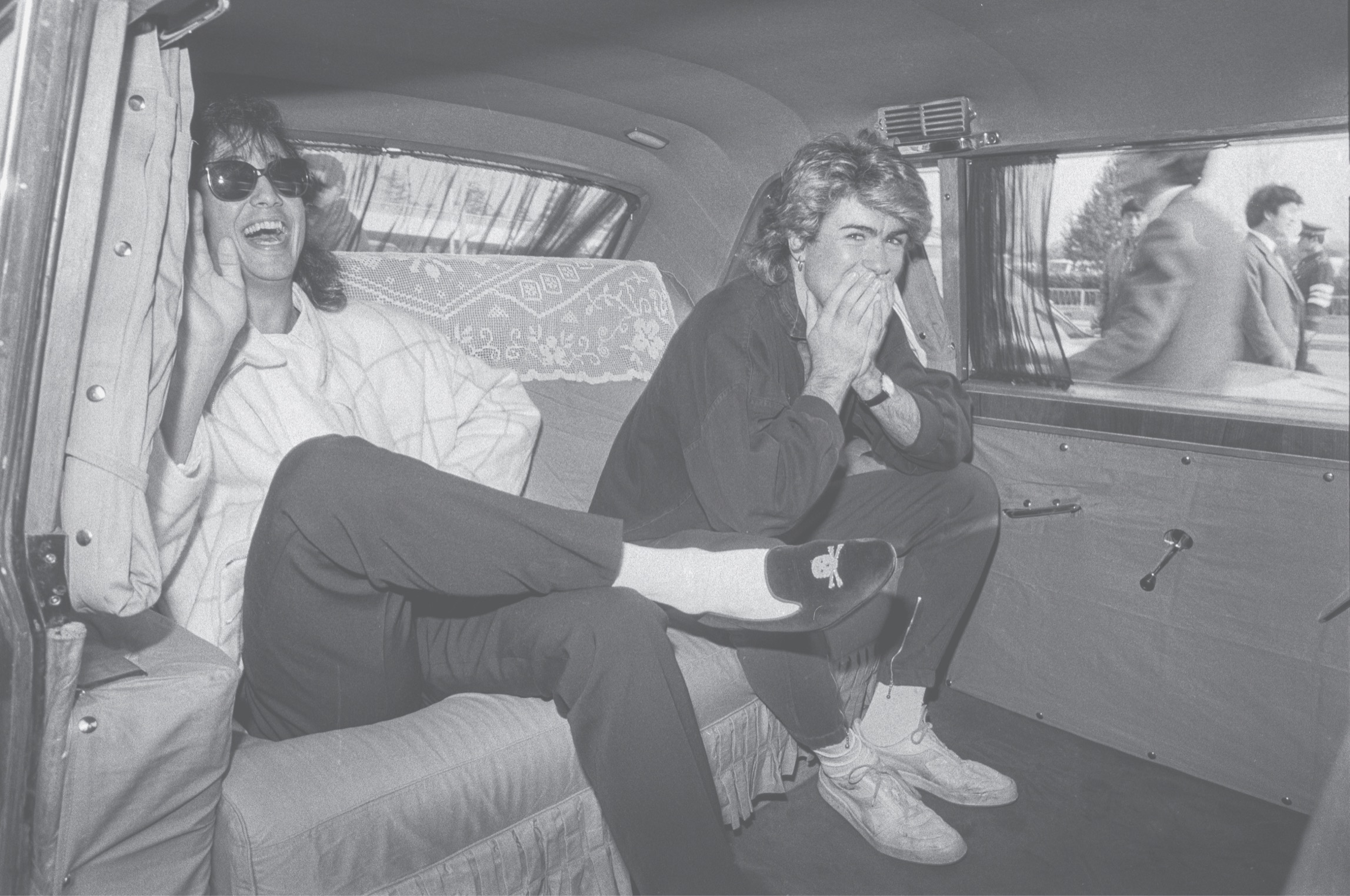

While I was intrigued by the gulf between life in China and my own existence in a Western liberal democracy, George could not have given two hoots. He was concerned solely with the music. Despite the eye-opening strangeness on display beyond our touring bubble, he remained cocooned inside, preoccupied with the latest international and album charts and, in particular, news of Make It Big’s latest sales. He’d become obsessed with the numbers. It was his only real measure of success and so functioned as a barometer of how he was growing as a songwriter. By comparison, reviews and column inches meant little to him. In China, he only left his hotel room for shows, or the next VIP meet-and-greet on the itinerary. And when he did, trailed by a gaggle of Western photographers and journalists, he took very little interest in the local culture, architecture or landscape around us. The physical experience of travelling just didn’t appeal to him. Music was so all-consuming that he rarely considered anything else. It bordered on pathological, and our radio plugger, Gary Farrow, was hounded by George for the latest mid-week chart positions, radio plays and sales numbers. Hits indicated that his songwriting was good. Number 1s meant it was the best. As far as George was concerned, our Chinese adventure could only be considered worthwhile if it fuelled global record sales.

In an effort to squeeze greater exposure from our trip, Simon felt we should document it on film. Then he chose director Lindsay Anderson, who was famous for bleak social realist films like This Sporting Life and Look Back In Anger. While the value of capturing everything on film was obvious enough, the choice of Anderson as director seemed absolutely bonkers. Simon had liked the idea of using him because his involvement lent the project gravitas and artistic credibility, while George was all for it simply because he admired Anderson’s political and social outlook, but neither made him the right choice. But although I struggled to see the point of having someone seemingly so totally at odds with the idea of a Wham! publicity stunt, I played along whenever the cameras were pointed at me. If I’m honest I wasn’t sure anything was going to come of it all.

It would not be through any lack of material, though. If our second show was anything to go by, Whamania seemed to be trying to find expression. In Canton, there was far more raucous energy in evidence and fans were even allowed to dance in their seats. Then the sax introduction to ‘Careless Whisper’ triggered an outbreak of actual screaming! But perhaps the most memorable image of the trip ended up being a much more affecting one. The sight of me and George posing on the Great Wall of China with a three- or four-year-old boy dressed in a military uniform, an officer’s cap perched on his head, appeared to sum up the gulf between us. And it was this cultural divide that seemed to capture the imagination of the world’s media. It may not have had an immediate effect on record sales, but it made Wham! feel like a global cultural phenomenon.

George always wore a tea cosy on his head for long-haul flights.

I returned home grateful for the liberties that allowed us the freedom to express ourselves. China had been like visiting the moon.

Sadly, Lindsay Anderson’s film failed to capture it all in anything like the way we had hoped. George and I arrived typically late to an intimate screening of the film, now titled If You Were There. We needn’t have bothered. The film was exactly what I’d feared: a well-shot but drearily worthy look at life in a communist state, rather than the exciting adventures of a Western pop band in China. George was unimpressed, as was I, and, for now at least, the film was junked as a project in need of dramatic remedial work. The tone and style of the movie displayed so little understanding of what was required that, if it was ever going to see the light of day, it would effectively have to be remade, salvaging whatever we could from the original material. It was a real missed opportunity, but not quite the final sting in the tail our trip to China had to offer. There was also the bill. We had paid for everything only to discover that any money we’d made would be staying in China because the authorities would not sanction cash transactions to non-nationals. A shipment of several hundred worker’s bicycles was offered in lieu of cash, but we politely declined.