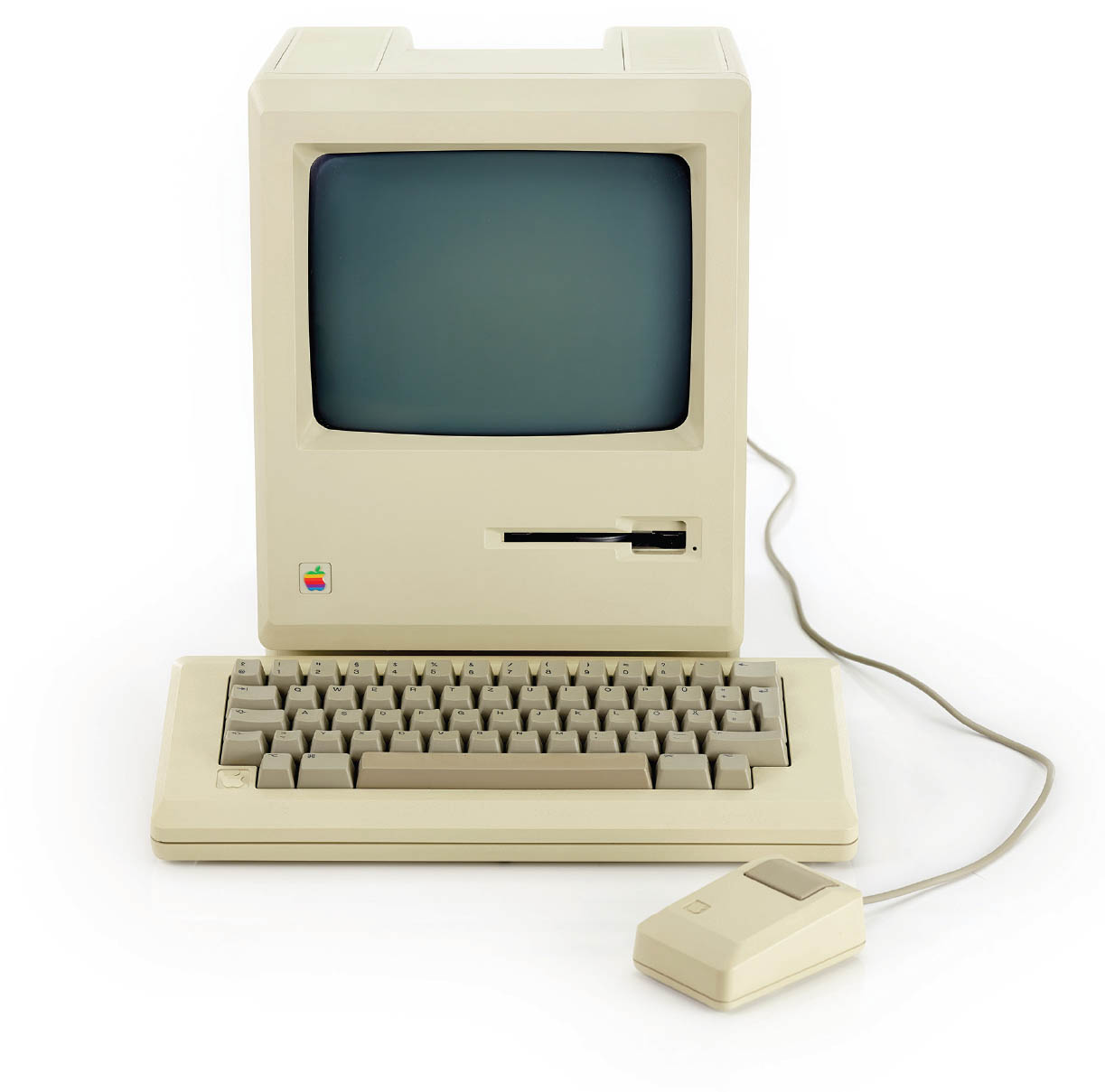

THE MACINTOSH COMPUTER This early desktop computer brought computation to the masses. Designers such as April Greiman, Zuzana Licko, and P. Scott Makela seized the potential of this crazy new machine.

THE MACINTOSH COMPUTER This early desktop computer brought computation to the masses. Designers such as April Greiman, Zuzana Licko, and P. Scott Makela seized the potential of this crazy new machine.

STEVE JOBS INTRODUCED THE ORIGINAL MACINTOSH COMPUTER IN 1984. WHILE SOME DESIGNERS SAW NO USE FOR THIS NEWFANGLED TOOL, MANY OTHERS TOOK ONE LOOK AT ITS INTUITIVE GUI AND PURCHASED THEIR OWN MACHINE. Desktop publishing and multimedia became buzzwords of the 1980s and ’90s. Laser printers and video cameras put production tools into designers’ hands, leading to more iterative, user-tested approaches to work. Alternatives to mass production suddenly became possible, an opportunity explored in depth by Muriel Cooper in her Visible Language Workshop at MIT. The digitization of type led to a surge in type design. Just van Rossum and Erik van Blokland of LettError began to investigate what happens when type shifts from a static form to a set of parameters. Freed from the need for expensive equipment and specialists, designers including Zuzana Licko and P. Scott Makela—much to the dismay of Swiss style modernists—looked beyond traditional forms to bitmapped shapes and flexible, layered, chaotic images. As mass-market personal computers spread across the United States, computer scientist Alan Kay, pioneer of the GUI, advocated for a society of individuals who could code. He urged the public to seize control of the computer medium, encouraging people to use computers to generate their own materials and tools. A disciplinary debate had been ignited that continues today: should designers learn to code?