The Future

In the fall of 2011, 3.5 million Russians, beginning with Vladimir Putin, venerated holy relics from a monastery on Mt. Athos said to be the belt that the Virgin Mary wore more than two thousand years ago when she was pregnant with Jesus. Over the course of seven weeks, the relics traveled to five different cities in Russia; nearly 1 million people in Moscow alone lined up, sometimes waiting up to twenty-four hours in damp, chilly weather to be admitted to Christ the Savior Cathedral. Nearby were warm buses provided by city officials where people could sit for a few minutes or get a cup of hot tea. Hundreds of police officers and medics provided logistical support.1

As people stood outside the cathedral, they sang hymns to the Virgin Mary and venerated small, inexpensive icons that they had brought along. My friend Elena later compared the long night in line to one of Orthodoxy’s ascetical disciplines. As she and her friends stood miles distant from the cathedral, they wondered whether they would survive the demands on their bodies and emotions. The experience was pushing them to their limits. But, as she told me later, just when they thought they could endure no longer, a power from beyond themselves propped them up. They reached the church, fell down, and venerated the relics. Elena and her friends had truly accomplished a spiritual feat.

Orthodox believers normally spend a few minutes venerating relics: they cross themselves, bow, and kiss the reliquary. As the crowds grew larger and larger, however, Church authorities had to speed up the process. At one point, they considered placing the relics in an airplane that would fly the belt over Moscow, distributing its power to those who reverently waited below. In the end, they kept the relics on earth but placed them on a canopy beneath which venerators walked, one after another, at a steady pace. All who wished would eventually make it into the cathedral.

Patriarch Kirill declared that this public outpouring of religious piety confirmed that Russia was truly Orthodox. But skeptics noted that other relics of the Virgin’s Belt are permanently on display in another Moscow church; there is no media frenzy about them, and no one lines up day after day to venerate them. The Virgin’s Belt reflects all the possibilities and ambiguities of Russia’s Orthodoxy today—and, perhaps, of religion in general. Russia is somehow Orthodox, and yet this “somehow” is difficult to define and measure. Church, society, and state interact in complex, unpredictable ways to produce different kinds of Orthodoxy, each of which has adherents and detractors.2

Political scientist Irina Papkova speaks of three major groups in the Russian Orthodox Church: the traditionalists, the liberals, and the fundamentalists.3 Building on her work, I suggest five kinds of Orthodoxy: an “official” Orthodoxy represented by the patriarch and the institutional Church, with its exclusive claims to administering the sacraments and ordaining clergy; a moderate Orthodoxy, which supports modest Church reform for the sake of securing the institutional Church; a liberal Orthodoxy loyal to the institutional Church while calling for democratic reform; a conservative Orthodoxy, also within the institutional Church but critical of its accommodations to a liberal culture; and a “popular” or “unofficial” Orthodoxy that thrives outside of the institutional Church yet draws on its key symbols, narratives, and rituals. Like Papkova, I acknowledge that any such categorizations are inexact, with a range of positions within and across types.

Official Orthodoxy is based on the principle of cooperative Church-state relations and symphonia. In Russia, as anywhere in the world, religious organizations have to work closely with government officials. To erect a church, synagogue, mosque, or religious school involves building permits and zoning regulations. Religious organizations face government mandates with which they must comply or for which they must seek exemptions. In a highly centralized state such as the new Russia, the Church has all the more need to work cooperatively with the government, especially in relation to religious education and social ministry. But this cooperation has come at a price. A public image of privilege and wealth has made the Church fair game for criticism. Much of the Russian media—and some parts of the Russian population—have come to regard Orthodoxy as a corrupt, wealthy, and authoritarian institution that is concerned with self-preservation, not advancement of a religious vision of deification and transfiguration.

Official Orthodoxy might have hoped that it would be otherwise. When Kirill was enthroned as patriarch in 2009, he appeared to be the perfect person to lead the Church into a new era of in-churching.4 During the Soviet period, he had been associated with the Church’s more liberal wing under the leadership of Metropolitan Nikodim of Leningrad. In that context, “liberal” had especially meant openness to ecumenical dialogue with Western Protestants and Catholics and their concerns for human rights and social justice. In 1989, Kirill was appointed head of the Church’s Department of External Church Relations. His prominence grew as he directed the writing of the Social Concept and then a major Church document on human rights. Rumors regularly surfaced about Kirill’s moral integrity—cooperation with the KGB during the Soviet era, expensive personal tastes, and even shady business dealings. He nevertheless successfully projected the image of a dynamic, reform-minded leader. An eloquent speaker, he had been publicly commended for his command of the Russian language. His public charisma reminded some Orthodox, especially in more intellectual and progressive circles, of Pope John Paul II.

Kirill’s election to the Patriarchate seemed to signal that the institutional Church would no longer hide behind rules and traditions but rather demonstrate its openness to society. As a headline in the New York Times declared, “Russian Orthodox Church Elects Outspoken Patriarch.”5 Kirill immediately called on the Church to see all of society as its mission field, even atheists and aggressive, Hell’s Angels–type bikers. His popularity was such that he could fill a huge stadium in St. Petersburg with enthusiastic Orthodox young people.6

But such exuberance did not last long. By 2011, the institutional Church no longer seemed to represent national rebirth but rather repressive power politics.7 In the fall, the patriarch’s representative for relations with society, Father Vsevolod Chaplin, provoked media ridicule when he called for instituting a national dress code (because women’s skirts were too short) and for removing certain literary classics from the high school curriculum, such as Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (because they supposedly exhibited pedophilia).

In December 2011, large anti-Putin demonstrations took place in Moscow and other cities, further complicating the Church’s public image. Chaplin initially adopted a conciliatory stance, calling for the state to enter into dialogue with its opponents.8 Soon afterward, however, Kirill gave full-fledged support to Putin’s candidacy for the presidency, declaring that the Putin era had been a “miracle of God.” Moreover, Kirill asserted that Orthodox believers “would stay home and pray,” not attend protest demonstrations.

In February 2012, another incident cast harsh light on the Church. Five members of a feminist art collective known as Pussy Riot slipped into Christ the Savior Cathedral, donned brightly colored ski masks, and kicked their legs and pumped their fists in front of the iconostasis as they performed a song accusing the patriarch of believing in Putin, not God. Guards quickly escorted the women out of the church, but a video recording of the event went viral on the Internet. Church authorities insisted that the women either repent publicly or be prosecuted. Three of the women were eventually sentenced to two-year terms in prison colonies.

Not long afterward, the media revealed that Kirill, despite his monastic vows, owned a luxury apartment on the Moscow River in which he housed a rare book collection. Kirill had reportedly received nearly $700,000 in compensation from an upstairs neighbor whose renovation work caused extensive damage to the books. A second event proved even more embarrassing. In 2009, critics had spotted a $30,000 Swiss Breguet timepiece on Kirill’s wrist when he lifted his arms during church prayers on a visit to Kiev.9 Kirill vehemently denied the accusations. In April 2012, however, the issue surfaced again, when the patriarch’s website published a photo of him sitting with the federal minister of justice at a table. In the photo the Patriarch wears no watch—yet a reflection of the controversial timepiece appears on the highly polished tabletop. Kirill’s Photoshop doctors had apparently overlooked it in their haste to rescue his public image.10

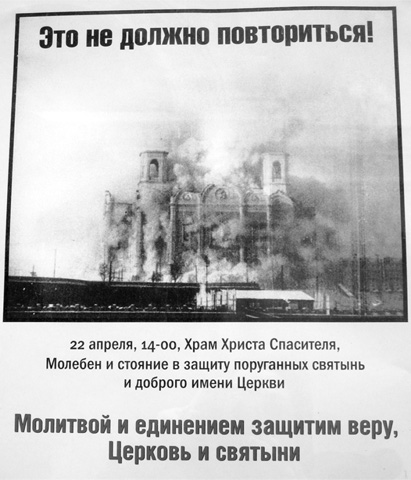

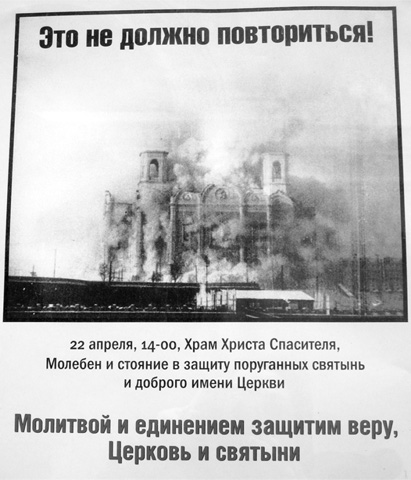

Church leaders began to speak of a new “anticlericalism” in Russian society. Some loyal supporters of official Orthodoxy saw an organized conspiracy, perhaps even directed by Western intelligence agencies, to discredit the Church. As one priest said to me, “They know that Russia’s strength comes from the Church. If they weaken the Church, they weaken Russia.” Church authorities called for a mass prayer service in support of the patriarch. Publicity flyers displayed a dramatic photograph of the implosion of Christ the Savior Cathedral on December 5, 1931. The headline beneath the photo read, “This Must Not Repeat Itself! With Prayer and Unity We Will Defend the Faith, the Church, and Our Holy Things.” On the back of the flyer, in an appeal that would also be read from the ambo of every parish, the Highest Church Council declared: “Anti-Church forces fear the growing power of Orthodoxy in the nation. . . . To these forces are joined others that promote the false values of an aggressive liberalism, for the Church is unbending in its opposition to such anti-Christian phenomena as the recognition of same-sex unions, the freedom to express all desires, unbridled consumption, and the propaganda of ‘anything goes’ and licentiousness. In addition, these attacks on the Church are useful to those whose business interests are being hurt by the program to erect new churches.”

Leaflet calling for prayer service to defend the Church, featuring

the implosion at Stalin’s order of Christ the Savior Cathedral in 1931

(author’s photograph)

The declaration went on to list several recent incidents in which churches and icons had been desecrated, beginning with the Pussy Riot action, and compared the current “campaign” against the Church with Bolshevik attacks on the Church in the early twentieth century. On April 22, an estimated sixty-five thousand believers gathered for the prayer service on the square outside Christ the Savior Cathedral. Parked nearby were rows of buses that had transported thousands of people from outside Moscow to the event, an operation organized so quickly and efficiently that it had clearly required state assistance.

A year later, events in Ukraine posed additional challenges to Russia and official Orthodoxy. When Putin moved to annex Crimea and support separatists in eastern Ukraine, Patriarch Kirill sought to stay above the political fray, repeatedly calling on both Ukrainian government forces and the rebels to lay down their arms and negotiate a peace. However, in failing to support the EuroMaidan Revolution or condemn Russian intervention in Ukraine loudly and clearly, Kirill appeared to ally himself with Russian state interests. Chaplin stoked further suspicions about the Church’s position when he criticized the West for trying to impose on other countries a brand of democracy that results in moral and religious decay.11 In December 2015, the patriarch abruptly dismissed Chaplin, who had earlier called Russia’s intervention in Syria in support of President Bashar al-Assad a “holy war,” but there was no sign of a change of course in Church-state relations.

If the patriarch and official Orthodoxy have spoken confidently of in-churching Russia, other Church people openly admit that efforts at re-Christianization have fallen short. To their mind, Russian society is not moving toward “in-churching” but rather toward “de-churching.” Some of these voices are moderate; others are liberal or conservative. What they share in common is a deep concern that Russian Orthodoxy has failed to win a new generation to the Church and a living faith.

Father Vladimir Vorob’ev, rector of St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University, is a thoughtful “moderate,” well connected in the institutional Church but also able to pose critical questions about it. He notes that too many people who turned to the Church at the end of the Soviet period did not know how to raise their children in Orthodoxy. Because the Bolshevik state had torn people away from Russia’s organic Orthodox traditions, parents were unable to offer their children an example of personal faith won through repentance and suffering. Instead, they thought that their children would become Orthodox if they simply forced their children to go to church or an Orthodox school.

Vorob’ev also cites the problem of priests whose personal behavior put up barriers to active lay Church participation. The priests whom the Church hastily ordained in the 1990s often raised money to renovate churches and pay their salaries by charging exorbitant rates for basic Church services to individuals, such as baptisms and funerals.12 People began to regard the Church as a business enterprise rather than a community of faith. An additional problem was that many of these priests were young and lacked spiritual maturity. They were unable to hear confessions properly or offer genuine spiritual guidance.

The effects of de-churching are increasingly apparent at St. Tikhon’s, says Vorob’ev. Today’s students lack basic grounding in Orthodoxy and Russian culture, and often show little interest in acquiring them. Vorob’ev suggests that the Church must do much more to become a genuine community of mutual support and care if it is to attract young people and incorporate them into its life.13

Igumen Petr (Meshcherinov), who served for many years as head of the Patriarchal Center for the Spiritual Development of Children and Young People, is another “moderate” voice, although his analysis is more stinging. Petr notes that as many as two-thirds of children raised in the Church will eventually leave it: “For contemporary post-Soviet families, being ‘churched’ has been stripped of any genuine Christian content. It has become a peculiar mix of ideology, magic, and a ‘Soviet’ complex mimicking an Orthodox way of life: irresponsibility being presented as ‘obedience’; disrespect for oneself and others as ‘humility’; contentiousness and spite as ‘the struggle for the purity of Orthodoxy.’”

Petr argues that the Orthodox Church has reduced itself to a social subculture that is obsessed with enforcing certain traditions—the Old Style calendar, Church Slavonic in the liturgy, and rules about fasting—even though all these practices are historically conditioned and not divinely mandated. Moreover, says Petr, too many Russians have concluded that because of their Orthodox identity they are morally superior to other peoples, and that to be Christian means to enjoy worldly power and success. He refers to popular Orthodox media outlets that are obsessed with Russia’s special spiritual path in contrast to a decadent West, or that long for a return of empire and monarchy. He adds that even many people who have entered deeply into Orthodox life now feel alienated from the Church. They do not experience freedom and encouragement to grow in faith. Instead, the Church constantly communicates an anxiety that its adherents may fall into heresy if they think too much for themselves. A spirit of moral judgmentalism has replaced the joy and mercy that should characterize the Christian life. Ritualism has taken the place of faith.

Like Vorob’ev, Petr calls for the Church to be a eucharistic community in which people experience solidarity in love. The Russian Church today needs a new language and a “pastoral pedagogy” that points people away from worldly privilege and power to heaven on earth. In-churching in the sense of attending the Divine Liturgy is not enough. Ritual and tradition matter only if they lead to life in Christ.14 People associated with the Church’s department for work with young people made a similar point to me: a younger generation of Orthodox believers is searching in the Church for life meaning and spiritual fellowship, not rules. They are interested in such people as Aleksandr Men’, who had the courage to think deeply and critically about Christian faith.15

Other critiques of the official Church go even farther, calling for “liberal, democratic” reform. In 2011, Russia’s major Russian cultural television station (Channel 24) broadcast a documentary film, Heat (Zhara), which traces the history of the catacomb church of the 1960s–80s and several of its leading priests, including Aleksandr Men’. The title refers to the huge peat moss fires that burned in the summer of 1972 in drained swamps outside of Moscow—at a time in which some Russians began quietly turning to Orthodoxy, away from Marxist-Leninist ideology. The film has resonated among many of my Orthodox friends who feel that the Church has lost its way since emerging from the underground and acquiring social prestige and political influence. They see a repetition of the Soviet era, when the official Church yielded to state control in order to secure a measure of public institutional life—including the ability openly to celebrate the liturgy and the Eucharist—but compromised its freedom and integrity.

I remember sitting with a group of theologians and philosophers discussing an open letter that had been quietly circulating in Orthodox intellectual circles in Moscow in early 2012. Signed by O. Bugoslavskaia and entitled “Reason to Doubt,” the letter accused the Church of cultivating a smug moral and religious arrogance. Orthodox believers were being told to avoid non-Christian art and literature rather than to learn from them and assess them thoughtfully. Some believers were refusing to think for themselves, consulting instead their spiritual father even for the simplest of matters. And, Bugoslavskaia added, when Church authorities asserted that all power comes from God, they were simply supporting the political status quo rather than motivating people to work for a more just, humane world.

Other Orthodox figures have directly challenged the Church hierarchy. Sergei Chapnin, dismissed in December 2015 from his position as editor of the Patriarchate’s official journal, has drawn a sharp contrast between the Soviet “dissident” church and today’s official Church. Chapnin talks about how he loves to contemplate photographs of Aleksandr Men’—as other believers, it seems to me, might peer at icons of a saint—because in Men’ he sees someone of “depth, wholeness, concentration and, at the same time, simplicity, lightheartedness, and inspiration.”16 Father Aleksandr, according to Chapnin, maintained a deep and clear sense of “privateness.” What Chapnin has in mind is Father Aleksandr’s ability to live “without the government.” “Privateness” does not mean a privatized or individualistic faith but rather the freedom that comes from being oriented by God, not by any social or political authority.

Chapnin worries that the Church today has not overcome a “Soviet mentality” that concerns itself only with how the state will support or undermine the institutional Church. “Post-Soviet civil religion” is focused on Orthodoxy’s contributions to Russian national identity rather than humans’ ultimate ends before God. For Chapnin, a Church that in the 1990s represented hope with its vision of an alternative society has become a “Church of empire,” a civil religion “without God,” that consistently supports the political status quo and never places it under divine judgment.17 Such a Church, says Chapnin, fails to represent the true values of Christian faith to society.

Cyril Hovorun, a Ukrainian priest-monk of the Moscow Patriarchate, has argued along similar lines. For Hovorun, the events on Kiev’s Maidan in 2013–14 now challenge the Russian Orthodox Church to develop a political theology that focuses on society rather than the state. Such a Church would offer a free space for people to develop democratic habits of critical thinking about, and deliberative negotiation of, social problems. Such a Church would not seek to preserve, with government assistance, an Orthodox identity over and against the West but rather forge alliances with other religious groups and social forces to promote a more just society. Hovorun contrasts the Russian Church with those churches in Ukraine that won the people’s trust by supporting the EuroMaidan and are now able to contribute to a vital civil society.18

Notwithstanding these sharp critiques of the official Church, I have seen how some Russian parishes do cautiously nurture a progressive vision of Church and society. The Feodorovskii Cathedral in St. Petersburg has skillfully negotiated Russian political and ecclesiastical realities while offering an alternative to them.19 The glorious edifice, constructed in the early twentieth century in honor of the three hundredth anniversary of the Romanov family’s ascension to state power, was turned into a milk factory during the Soviet era. By the time the Church regained ownership in 2005, thirteen years after the state promised to return it, only a dilapidated, brick/concrete shell remained. Restoration efforts would take another decade of sophisticated planning, negotiating, and fund-raising. Boris Gryzlov, head of the Russian Duma and chairman of Putin’s United Russia Party, headed up a board of directors. Among the chief financial sponsors was Vladimir Iakunin, the country’s railroad magnate until 2015 and a close associate of President Putin. Rededicated on September 15, 2013, the four hundredth anniversary of the Romanov ascension to power, the cathedral is again an architectural wonder—and more.

The new edifice includes a lower church for which funds had failed when the cathedral first opened in 1913, on the brink of the First World War. The spatial arrangement, frescoes, and icons are the work of Father Zinon (Teodor), one of Russia’s most creative icon painters—and a monk who has been criticized and even punished for his criticism of a narrow-minded Church. When I first walked into the lower church, I was stunned by its beauty. The space, filled with light, is open and welcoming. Rather than a traditional multistoried Russian iconostasis, only a low barrier marks the separation of nave and altar. Worshippers can see and hear all the liturgy. The space invites not clerical control but rather a liturgy that is the work of both the priests and the laypeople. And I saw for myself how hundreds of parishioners—men and women, adults and children, clergy and laity, and conservatives and liberals—feel like family here, despite their social and political differences.

At the Feodorovskii Cathedral, Orthodox symbols have inspired a participatory, even democratic vision of Church and society. One of the cathedral’s assistant priests is a student of contemporary Western philosophy of science and is writing a dissertation on Theodor Adorno and the Frankfurt School of social theory. Another assistant priest serves as a vice rector at the St. Petersburg Theological Seminary and Academy, and regularly travels abroad to lecture about icons and Orthodox theology. The head priest, Father Aleksandr Sorokin, welcomes ecumenical dialogue and cooperation with Catholics and Protestants in matters of social ministry. And parish members vigorously discuss and debate contemporary political issues—and even Russian military actions in Crimea and eastern Ukraine.

Another kind of Russian Orthodoxy joins in the call for Church reform, but along “conservative” or “fundamentalist” lines and therefore in sharp contrast to Chapnin’s or Hovorun’s admiration of Western democracy. Adherents of this conservative Orthodoxy typically anticipate an apocalyptic battle between true and false believers—and relegate Church and state leaders to the anti-Orthodox camp. Some political observers judge these conservative circles to be larger and more powerful than the Church’s liberal wing.20 But just as those Orthodox believers who seek a more progressive Orthodoxy interact in different ways with state, society, and official Orthodoxy, so, too, do these conservatives. Some remain firmly within the bounds of the institutional Church, while others exist on its outer fringes.

Conservative Orthodoxy finds one of its representative centers in a historic Moscow church, St. Nicholas in Pyzhakh, just down the street from St. Elizabeth’s Martha and Mary Monastery. In the 1920s, one of the monastery’s last priests briefly served at St. Nicholas after the Bolsheviks closed St. Elizabeth’s community. Today at St. Nicholas, icons of St. Elizabeth and Patriarch Tikhon have prominent places on the iconostasis before the chief altar. The head priest, Father Aleksandr Shargunov, translates classic Western poetry into Russian, publishes widely on theological and spiritual topics, and teaches at the Moscow Theological Seminary and Academy.

After the collapse of Communism, Father Shargunov gained notoriety for his conservative politics. During the 1993 constitutional crisis, he called on Orthodox believers to defend the Parliament when President Yeltsin used military force to quash opposition to his program of democratization, and Shargunov’s parish played an active role not only in opposing liberal Orthodox priest Georgii Kochetkov but also in shutting down the 2003 Sakharov Center art exhibition Danger, Religion.21 During these same years, Shargunov became well known for promoting canonization of the new martyrs and especially Tsar Nicholas II. The parish commissioned an icon of Nicholas that thousands of people lined up to venerate after the Bishops Council glorified him in 2000. Father Aleksandr began regularly celebrating an akathist (special Orthodox hymn) to Nicholas II and added his icon to the iconostasis of a side church altar dedicated to the ancient St. Nicholas of Myra.

For the parish, as for conservative Orthodoxy more generally, Tsar Nicholas represents a prerevolutionary Russia in which Orthodoxy shaped all aspects of public life. In contrast to some Orthodox conservatives, Father Shargunov does not look for a restoration of a God-anointed tsar today. But he does appeal to Nicholas II to call both Church and state to account for their failure to protect Orthodox values in Russian society. Shargunov’s criticisms of the Church’s worldly compromises with the Putin government can be as sharp as those that politically liberal Orthodox believers make.

Father Aleksandr and his parish demonstrate how religious symbols help not only liberals but also conservatives imagine an alternative political order. Shargunov, no less than Chapnin and Hovorun, argues that the Church should be a community of love and peace. No less than “progressive” Orthodox believers, he appeals to the new martyrs when he calls believers to remain faithful to Christ in the face of social opposition. Where he differs from the liberals is in his definition of the kind of political order that follows from these shared symbols, narratives, and rituals. For him and his parish, the issues are not human rights and liberal democracy but rather pornography, abortion, and homosexuality.

Father Shargunov remains firmly within the institutional Church, but other conservative Orthodox believers take a more militant stance against it and its “liberals.” These fundamentalists have physically attacked people publicly demonstrating for civil rights for homosexual persons in Russia. Some of these Orthodox reactionaries regard as saints dubious historical figures whom a supposedly corrupt, politically accommodated institutional Church has refused to canonize. Ivan the Terrible is said to have defended “true Orthodoxy.” Rasputin was martyred for his faith in Holy Russia and his loyalty to its divinely anointed monarch, Nicholas. Even Stalin claims their admiration because at the beginning of the war he supposedly visited the holy elder Matrona and became a believer. And while Church officials do not publicly support these reactionary groups, they have failed to condemn them, perhaps fearing that they could become even more aggressive or schismatic. Not only I as a Western theologian but also many liberal and even moderate Russian Orthodox believers whom I know fault the official Church for its silence.

Nevertheless, Orthodoxy—whether in its official, moderate, liberal, or conservative forms—is more limited in social and political influence than we might expect. Anyone who spends years among Orthodox believers can forget that the Church is only one social organization among many. We can too easily accept the official Church’s assertion that most Russians are Orthodox. But, as we have seen, very few Russians are actually in-churched. Although honoring the Church in principle, they keep their distance from it in everyday life. And even those who do regularly attend the Divine Liturgy or observe the Church calendar are not necessarily interested in matters of deification, transfiguration, or Holy Rus’. Yes, Orthodoxy has shaped historic Russian culture, but in my more sociological moments, I see a Church that is barely noticeable in a pluralistic society—even if contemporary Russia appears less pluralistic than western Europe or North America. In a post-Communist world, Orthodoxy competes with many other social identities to define Russia. The Virgin’s Belt changed Moscow for only a few days.

No, not the long lines in front of Christ the Savior Cathedral but rather something else stays in my mind when I think about everyday Russian life. When my family and I lived in Moscow, I walked every morning from our fifteen-story Soviet-era apartment building to the metro through an underground pedestrian passageway lined with small kiosks. They offered everything from shoe repair to key copying to sale of inexpensive souvenirs and clothing. Next to the shop selling women’s underwear of various sizes, colors, and shapes was a tiny Church kiosk with a limited supply of Orthodox crosses, icons, calendars, and books. Orthodoxy, it struck me, has a firm place in Russian society again—but to the tens of thousands of people who passed those kiosks every day, it was just one more consumer option in a crowded marketplace.

What is perhaps more significant than trying to describe different types of Orthodoxy—symphonic, moderate, liberal, or conservative—is the phenomenon of different Orthodoxies that merge and diverge, wax and wane, and mean different things to different people at different times. I have argued in this book that something in all of these Orthodoxies holds forth a vision of the transfiguration of reality. This heaven on earth is not the material comfort or proletarian liberation that Soviet Marxism once taught. Rather, Orthodoxy promises intimate, trusting relationship between divinity and humanity and among humans. Here and now, even if fragmentarily and incompletely, people are able to pursue holiness and deification. They begin to take wonder at existence and overcome alienation and enmity.

I have further argued that this traditional Orthodox view of ultimate reality has assumed a special form in Russia, what I call Holy Rus’.22 In Russia, the longing for beauty, deification, and moral and spiritual transformation has been not only individual and personal but also social and national. Russians have believed that as a people and land they can shine with the divine light that has enlightened their greatest saints, such as St. Serafim of Sarov in the nineteenth century. As one of his companions reported, “I looked in his face and there came over me an even greater reverential awe. Imagine in the center of the sun, in the dazzling brilliance of its midday rays, the face of the man who talks with you. You see the movement of his lips and the changing expression of his eyes, you hear his voice, you feel someone grasp your shoulders; yet you do not see his hands, you do not even see yourself or his figure, but only a blinding light spreading several yards around and throwing a sparkling radiance across the snow blanket on the glade and into the snowflakes.”23

I have described how Church initiatives in religious education, social work, commemoration of the new martyrs, and parish life have the potential to draw people into this vision of Holy Rus’. And Russia, I have argued, is indeed a healthier, more vital society today because of these efforts. Russians are learning more about their nation’s historical roots in Orthodoxy; persons in physical and emotional need or on the margins of society are receiving love and practical assistance; new generations are honoring the victims of Bolshevism; and parishes are helping people experience genuine fellowship with God and each other. To be sure, the Church faces real limitations in each area. Russians are not always Orthodox, and they are not always Orthodox in ways that the Church would like. But because of the public revival of Orthodox symbols, narratives, and rituals, Russians at least have the opportunity to glimpse Orthodoxy’s vision of transcendent beauty and become aware of a different dimension of their existence.

For me, then, the place of Orthodoxy in the new Russia goes far beyond questions of Putin and the patriarch. As parishes and monasteries, lay brotherhoods and sisterhoods, and Church social service programs bring Orthodoxy closer to everyday Russian life, the Church has again become part of the nation’s cultural and physical landscape. Russia is slowly being “reenchanted” with the help of Orthodox symbols, narratives, and rituals. Orthodox life in all of its complexity is no longer hidden in catacomb churches or private corners of people’s lives but rather manifests itself in full public view.24 As the Church becomes a comprehensive social presence, reminders of divine mystery are never far away, shaping not only institutional Church life but also a popular unofficial Orthodoxy outside of its walls—as apparent on Kreshchenie, perhaps the most popular of all the Church’s holy days.

Kreshchenie (literally, Baptism) is celebrated twelve days after Orthodox Christmas. It is associated both with Christ’s baptism in the Jordan River by John the Baptist and with Theophany (in Western Christianity, Epiphany), the manifestation of God as Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. On this day, Orthodox churches bless the waters of the earth, a blessing that for the Church points to the salvation and transfiguration of all reality through Christ. Kreshchenie offers more than a guarantee of personal blessedness beyond death; it points to the divine glory that already fills the earth.

Several years ago, I traveled to a historic monastery several hours outside Moscow to participate in the celebrations. I arrived on the eve of Kreshchenie, and the monastery church was already packed. I could barely squeeze my way to the front. “There must be even more people here than at Christmas or Easter,” I thought to myself. The service was long but spectacular, with a procession of the clergy in splendid robes. The singing of the monastery choir was heavenly, and worshippers participated enthusiastically in the Church’s prayers. The high point came when the priests and monks gathered in the back of the church around four huge stainless steel vats of water, each perhaps twelve feet high and twelve feet in diameter, to perform the “Great Blessing of the Waters.” After chanting prayers and dipping a large gold cross three times into each vat, the priests drew water into bowls, walked through the church, dipped long brushes into the bowls, and wildly threw drops of water over the icons and the worshippers. People pushed closer, hoping to get as wet as possible—and I was struck by the joy and delight that filled their faces.

When the service ended near 2 a.m., hundreds of people lined up with plastic bottles of all sizes and shapes to take water home with them. They would carefully guard it over the rest of the year, adding it to their food and drink or even their mop water, to sanctify themselves and their homes. The Church regularly performs blessings of water and teaches that the blessing at Kreshchenie is not different from or superior to the others. But many people believe that kreshchenskaia voda (baptism water) has a different molecular composition than regular water, endowing it with special healing and protective properties.

Outside the church, I met my friend Father Vasilii, a young, energetic monk and rising star in the official Church. His twenty-something face sported a few straggly chin hairs, the only beard that he could grow. “Let’s go,” he said. “Another blessing of the waters will take place down by the creek.” We followed the clergy and a large group of laypeople through the huge monastery gates, around the high, thick, white monastery walls, to a narrow path leading to a small wooden hut over the tumbling stream. People had lined up to enter the structure—one side for men, the other for women—and dip into a pool that had been carved into the riverbanks. Other people were filling their bottles from a spring next to the path.

Kreshchenie falls on January 19, usually the coldest time of the year; Russians even refer to the phenomenon of the kreshchenskii moroz (baptismal deep freeze). This year was no different. The night sky was crystal clear, the stars shone bright, and temperatures had plunged to zero degrees Fahrenheit. Out here the crowd was rowdier than in the church. A number of men were sharing bottles of vodka. People were laughing, talking loudly, and stamping their feet to try to stay warm. A hush came over them as the priests blessed the waters in the stream and the spring, but immediately afterward the noise started up again. In an effort to restore some semblance of pious order, one of the monks began chastising the drunken revelers. Other monks distributed flyers articulating a theologically correct understanding of Kreshchenie and cautioning people against popular superstitions. A few crumpled sheets already lay on the ground.

In recent years, the Church’s blessing of the waters has merged with the Soviet tradition of a January “polar bear” swim. On Kreshchenie, Church people often carve a hole in the shape of a cross into the surface of a frozen lake or river, the priest dips a cross into the icy waters below, and members of the public plunge in. My friends Evgenii and Natalia—faithful, in-churched Orthodox believers—spoke with delight about the hundreds of Muscovites who every year on Kreshchenie line up along the river that runs by their church outside Moscow. On Kreshchenie in 2015, the bishop of St. Petersburg joined other polar bears in the Neva River near the famous Peter and Paul Fortress.25

This combination of different Orthodoxies leaves me feeling conflicted. On the one hand, I appreciate Orthodoxy’s ability to embed itself in popular culture. That kind of popular Orthodoxy enabled the Church to survive the Soviet era. Even though parishes and monasteries were closed, ordinary believers continued to keep icons in their homes, draw water from holy springs, baptize their children (or grandchildren), and observe rituals connected to holy days and seasons. And today, too, the Church depends on a “people’s Orthodoxy.” Their piety permits the Church to imagine that it is stronger than ever in Russian society. Moreover, monasteries and parishes raise much of their money from people who come to venerate their holy things and places, even though many of these pilgrims are not in-churched.

On the other hand, I worry about “believing without belonging,” however much it now characterizes not only Russia but also much of the historically Christian West.26 In that kind of Christianity, personal rituals become more important than Church doctrine or practices—matters that I as a theologian regard as central to Christian faith. And I know thoughtful Russian Orthodox Church leaders who share my concern that some kinds of popular Orthodoxy tend toward superstition. When that happens, venerators of holy things and places look for a practical payoff—say, a miraculous healing when all else has failed—rather than the transformed way of life that the Church calls salvation. Extraordinary “spiritual” experiences take the place of attending the Divine Liturgy, receiving the Eucharist, doing charitable works, and participating in parish life. The bishop of St. Petersburg undoubtedly wished to make a personal connection with those Russians who celebrate Kreshchenie but do not regularly go to church. But I agree with those Church leaders who worry that combining “the blessing” with “the swim” just further confuses the popular mind about the true meaning of Kreshchenie.27

The problem, as I see it, is not that the Church tolerates and sometimes even encourages this kind of popular religiosity. Over the course of Russian history, official Orthodoxy has never been able to monopolize sacrality within its own walls. As historian Gregory Freeze notes, the institutional Church has regularly had to recognize believers’ need for “direct access to the power of the sacred.”28 But as a theologian, I wish that the Church’s authoritative teachers would speak more openly about just how ambiguous a phenomenon this “popular Orthodoxy” really is. While it offers powerful glimpses of the transfiguration of reality, it also easily distorts or truncates the Christian message of personal sacrifice and self-giving love.

But, again, Russia has taught me to be cautious about my judgments. The line that I would like to draw between religious faith and social custom, Church and nation, or deification and superstition is not so clear. Popular unofficial Orthodoxy intersects in complicated ways with official Orthodoxy, Russia’s other Orthodoxies, and state efforts to use Orthodoxy for its own purposes.29 The result is still other ways of being Orthodox that draw upon yet go beyond either institutional Church life or the popular Orthodox religiosity characterized by Kreshchenie. And there are also people who have consciously left official Orthodoxy for something that they regard as more authentically “Orthodox.”

On the boat from Solovki back to the mainland, I met Tanya. As we traveled across the choppy waters of the White Sea on a glorious summer afternoon, she spoke with me in the way that only Russians can to a complete stranger who has mysteriously won their trust. As she told me her story, I slowly came to see all the complexities and contradictions of Orthodoxy in today’s Russia.

Tanya is a professionally successful, middle-class Muscovite who lives in a comfortable apartment and has enough money to travel extensively both within Russia and abroad. In the 1990s, she and her husband explored various Eastern and Western spiritualities but never settled into a religious community. Tanya nevertheless decided to be baptized in an Orthodox church. Several years later, she agreed to be godmother to her niece. Although she has heard of Aleksandr Men’ and says that he fascinates her, she has never read his books. She does not attend church services in Moscow, even though she keeps telling herself that she should. As she confessed to me, she is not even sure that she believes in God.

Tanya had nevertheless taken ten days of precious vacation to make the arduous journey to Solovki, where she had worshipped every day with the monks, made pilgrimage to Anzer and other remote sketes, walked in the expansive birch tree forests, and watched the sun set over the sea. She told me that she had glimpsed something precious there: a holy world. Never before in her life had she experienced such peace and joy. “I’m afraid that I will lose all of that,” she lamented, “once I’m back in Moscow.”

Tanya is not very interested in politics. If she bothered to vote, she would likely cast her ballot for Putin and his party United Russia, but she does not expect much of him or any other politician. She would rather devote her time and energy to her professional work and her two sons, now grown and looking for jobs. While she respects the patriarch, she does not pay attention to his public pronouncements. “The Church,” she told me, “should focus less on itself and more on doing good for others.”

I doubt that Tanya will ever return to Solovki, but when I visited her several years later in Moscow, we went for a stroll in the gardens next to the Danilov Monastery, where the Patriarchate has its offices. It was a winter evening, and night had fallen. A light snow swirled around us as we walked along the monastery walls and talked about our work and families. The setting again seemed to draw out our wonder and perplexity about life, where it takes a person, why we are who we are. Is Tanya Orthodox? She is not in-churched, but Orthodox symbols, narratives, and rituals touch her deeply. They somehow connect her to what it means to be Russian.

I got to know Marina and Sergii more than ten years ago in Kronstadt. Like Tanya, they live their Orthodoxy outside of the institutional Church. But while Tanya finds Orthodoxy to be elusive, if fascinating, Sergii and Marina regard themselves as serious believers—so serious, in fact, that they are willing, like the new martyrs, to suffer for their faith.

For many years, Sergii worked on a ship and was gone for weeks on end. Marina worked part-time as a translator and cared for their only child, Natasha. She was their “miracle child,” the child for whom Marina had prayed so fervently for so many years in front of miracle-working icons and relics. In her desperation, she finally sought out a man reputed to be a holy elder. Before she could explain her situation to him, he blurted out that she would indeed have a child. A few days later, Marina became pregnant.

In 2009, Sergii was seriously injured at work and had to go on disability. About the same time, he and Marina began attending a house church of the renegade Russian Orthodox Church Abroad under Metropolitan Agafangel (Pashkovskii), which consists of a handful of priests and congregations both within and outside Russia that have refused to recognize the 2007 union of the Moscow Patriarchate and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. A couple of years later, Sergii, Marina, and Natasha moved to the village of Dudachkino, a hundred miles east of St. Petersburg.

Dudachkino lies in an almost forgotten corner of post-Soviet Russia.30 Away from the main highway, roads quickly turn to dirt. Thick birch and pine forests are slowly taking over the unplowed fields. Villages are few and far between, and their small wooden houses tilt to one side. Many have been abandoned to the elements, as people move away in search of work. Dudachkino no longer has a school, a store, or even a bar. The “official” church, closed under the Communists in 1937, is now just an empty, rotting wooden shell. A few hungry, filthy dogs wander the street.

Perhaps because of its relative isolation, the village lent itself to a utopian project. In the late 1980s, as the Soviet Union was collapsing, Father Aleksandr Sukhov came here to organize an Orthodox community whose members would live and worship together while preparing for the end of time. Born in Siberia in 1955, Sukhov, like many of his generation, was baptized in infancy by his grandmother but grew up with no living connection to Orthodox belief or practice. When he came to St. Petersburg in the early 1980s to study law, he began, like many other intellectuals of that time, a deep spiritual search that brought him into the Orthodox Church.

Another turning point came several years later when he visited Nikolai (Gur’ianov), the renowned holy elder. To Sukhov’s astonishment, Father Nikolai blessed him to become a priest, although he warned Sukhov that he would have few friends or assistants. Four years later, Sukhov was ordained in St. Petersburg’s grand Kazanskii Cathedral and sent to Dudachkino to reestablish a parish. Father Aleksandr knew the area well. He had often come to its forests and swamps to pick berries and mushrooms. The sparsely inhabited expanses reminded him of Siberia. Land was cheap, and he bought twenty acres at the top of the hill near the village. A person of great energy and charisma, he soon attracted more than a hundred followers, many of whom would travel three or four hours by car or bus from St. Petersburg just to spend the weekend in the parish.

Almost thirty people eventually moved to the community. Living conditions were primitive. The wooden houses had electricity but no indoor plumbing. A nearby spring provided water. The only bathing was on Fridays in a Russian bania (bathhouse). The community strove to be self-sufficient, raising its own food. Father Aleksandr even cultivated grapes in a makeshift greenhouse so that the community could supply its own wine for the Eucharist. A cook prepared the community’s midday and evening meals. A young woman gave daily school lessons to the community’s only two children. Parishioners donated whatever financial resources they had to Father Aleksandr and accepted his spiritual authority. He assigned their work, heard their confessions, determined the daily schedule, handled money, and made community decisions.

One autumn several years ago, Sergii and Marina invited me to visit them. I felt as though I had suddenly stepped into Nesterov’s Holy Rus’. As we walked down the road, a tiny rose-colored chapel rose up to the left, and behind it a large wooden church, both dedicated to St. Michael the Archangel. One of its icons was miraculously exuding oil. On a ridge on the other side of the road stood two slender chapels painted in bright green and dedicated to the warriors who fought for Dmitrii Donskoi in his fourteenth-century battles against the Mongols. Farther up the road, we came to a small chapel in honor of the prophet Elijah, to whom the original village church had been dedicated. A miraculous apparition of the Mother of God had appeared in one of the chapel windows. Marina said that she could still trace it out; if I looked the right way, I could perhaps see it too. Next door was a parish house with a chapel on the first floor dedicated to St. John the Clairvoyant, an Egyptian anchorite of the fourth century. Across the road stood a church and bell tower painted in pale yellow and dedicated to St. Nicholas of Myra. The church was being used primarily by the sisters of a small monastery that Father Aleksandr had founded. Behind the Church of St. Nicholas—and still in the process of being constructed—was a large cathedral-like edifice. It would be dedicated to the Protection of the Most Holy Theotokos.

Sergii and Marina took their turns in the parish’s continuous reading of the Psalter, day and night, in the Chapel of St. John the Clairvoyant, something that otherwise takes place only in a few monasteries. Father Aleksandr celebrated the Divine Liturgy every morning in the Church of St. Michael the Archangel and vespers every evening, also usually in the Church of St. Michael. On the iconostasis, next to Mary with the baby Jesus, was a kind, motherly Rasputin holding the Tsarevich Aleksei on his lap. What kind of Orthodoxy was I now encountering? Several strands of religious belief had merged: conservative apocalypticism with utopian communitarianism, a rejection of official Orthodoxy with a popular Orthodoxy that finds the holy in everything around it, and the creation of a lonely lifestyle niche with the effort to be true to deep religious convictions in a modern, pluralistic society.

The community at Dudachkino has suffered for its uncompromising faith. Moscow Patriarchate officials excommunicated Father Aleksandr after he rejected their oversight because, he said, they were corrupt and had accommodated themselves to the state. Local residents and authorities have accused him of running a cult, even of planning terrorist attacks. The FSB (Russian secret police) has raided the community. Father Aleksandr has been physically threatened and taken to court—and has hired lawyers to defend his constitutional rights. Church buildings have been set on fire. Dudachkino’s Holy Rus’ does not fit with dominant official visions of Church, state, and society. Even some of his followers have worried that Father Aleksandr can be controlling, even abusive; he is known for bringing women to tears when they make confession before him.

On my last evening in Dudachkino, the solitary bell at St. Nicholas began to toll; the bells in the Church of St. Michael across the valley responded. The tempo started slowly but steadily accelerated over the next twenty minutes as the hour of evening prayer approached. Whether at home or in the fields, the members of the community put their work aside and walked across the fields or down the road to the church. When we arrived, only a few candles illuminated the dark space; the iconostasis glowed like burnished gold against their flames.

The beleaguered Orthodox believers of Dudachkino ushered me into a holy world in, yet not of, the hostile, secular world that surrounds them. Father Aleksandr began gently intoning the Church’s prayers. His followers bowed and crossed themselves. Sergii’s baritone and Natasha’s soprano voice constituted the entirety of the church choir in the balcony. I looked out the window. Night had fallen, and the everyday world was silent. All that I could hear now were Sergii’s and Natasha’s plaintive and haunting voices—“Lord, have mercy; Lord have mercy”—as though they were calling out with their deepest longings for a Dudachkino, a Holy Rus’, in which everything would finally be made good and right.

In the 1960s, famed sociologist of religion Robert Bellah argued that every people needs a civil religion: religious symbols, narratives, and rituals that unify it and anchor its identity in transcendent moral and spiritual values. He observed that in the United States, great national commemorative sites along the National Mall in Washington or widely observed national rituals such as Thanksgiving Day help the nation regularly remember and rehearse its highest, most noble identity.31 Although Bellah was later more cautious about the term civil religion—he saw how it could easily be misused for narrow sectarian purposes or to justify oppressive social-political arrangements—he continued to believe that transcendent symbols, narratives, and rituals can both elevate a people and call it to repentance. This kind of civil religion need not simply sacralize existing social arrangements; it can also judge these arrangements in terms of ultimate ideals of justice, freedom, and peace.32

I have often hoped that Holy Rus’ would play a similar function in Russia, that a religious vision of a transfigured people and place would bring Russians together and help them understand their unique value and purpose among the peoples of the world. Moreover, I have hoped that this Orthodoxy would retain a critical potential rather than simply endorsing symphonia and the current political order in Russia. And I have indeed seen how not only a progressive Orthodoxy at the Feodorovskii Cathedral in St. Petersburg but also an unofficial Orthodoxy in Dudachkino, which to a Western Protestant so easily distorts Christian faith, draw on the Church’s symbols, narratives, and rituals to nurture alternative social spaces. Wherever Church, state, and society negotiate the meaning of Orthodox symbols, narratives, and rituals, there is the potential for new visions of life together to appear. Remember, when it comes to social reform, never rule religion out.33

There is another reason not to count religion out. Western political scientists often remark on the importance of a vibrant civil society for the development of democratic politics. As people organize and participate in voluntary associations—clubs, political parties, social welfare societies, and churches—they learn democratic skills of negotiation and compromise. Those abilities enable them to participate in government, as well as to resist its excesses.34

Today civil society in Russia appears to be far less developed than in Ukraine or the Baltic states, despite a common Soviet legacy. The Putin government has increased state control in every area of social life—from the Internet to motorcycle gangs to university accreditation. The prospects for democracy appear poor because the space for civil society is so constricted.35 But Russia is not fated to despotism. In the early twentieth century, Russia experienced an explosive growth of voluntary associations that stepped into the breach as the tsarist regime crumbled under the burdens of the First World War and popular discontent. When the state proved unable to solve pressing social tasks on the ground, Russians successfully organized trade unions, local governments, and civic movements.36 And today the Orthodox Church provides a critically important space, however limited and imperfect, for this kind of civil society.37

Russians who enter deeply into Orthodox belief and practice envision a God who gives them the freedom to work for moral and spiritual transformation of themselves and their society. A profound commitment to human dignity undergirds that freedom.38 It is possible that some of Russia’s Orthodoxies will inspire people to think about what kind of political order can best protect human dignity and whether a democracy may do so better than centralized authoritarian rule.39 When Orthodox believers personally participate in the Church’s social ministries, they get to know people who suffer not only because of personal sinful choices but also because of unemployment, inadequate access to medical care, and social marginalization due to illness or disability. As the Russian Church endeavors to conduct its ministries more effectively, it learns from Western models of social care. We wait to see whether Orthodox believers will eventually develop social analyses that suggest the value of democratic arrangements for addressing these problems.

The icon of the new martyrs, as we noted, can be read as sacralizing the political order—or, alternatively, as holding rulers accountable to transcendent ideals of justice. The icon supports traditional Orthodox notions of a symphonia between Church and state—but also warns the Church that the state can quickly become demonic and turn against it, as happened under Communism. A Church that recognizes the dangers of a totalitarian state retains the potential not only to criticize Western individualism and consumerism but also to question an insufficient commitment to human rights at home.

The development of parish life and eucharistic fellowship depends on Orthodox believers who take responsibility for parish affairs. As they organize Sunday schools, social outreach to the needy, or building projects, they debate strategies, negotiate differences of opinion, and come to consensus. They practice democratic virtues, even if they do not use the word democracy or think of themselves as Western liberals. Even while respecting the authority of the clergy, they draw from their own experience in business and social life. A Church that is increasingly characterized by young urban professionals will also be shaped by their entrepreneurial skills and ways of thinking.

While greater democracy is possible in Russia, it is not inevitable. And even if democratic impulses do develop, Russia’s social-political order is apt to look very different from American, French, or German systems of government. We cannot yet say what role the Orthodox Church will play in advancing or restraining a distinctively Russian kind of democracy. Next to my principle “Never count religion out as a source of social reform” lies a second: “Religious phenomena are always ambiguous.” They can be socially repressive or liberating; they can stabilize existing arrangements or call them into question.

As Father Vasilii and I returned from the creek to the monastery, he told me that the previous year he had gathered the monastery’s youth group late in the night after the vigil. They went into the countryside, built a bonfire, and looked at the stars. The young men in the group stripped and jumped into a nearby pond. The two young women in the group, however, were hesitant. They were not active Church members and had never before celebrated Kreshchenie. Father Vasilii gently encouraged them. Finally, they, too, stripped off their clothes and dove into the icy waters. When they returned they were changed, he says. The polar bear swim had become their initiation into the Church.

The next morning Father Vasilii invited me to travel with him and his monastic brothers to a neighboring town, where they would bless the waters again. When we arrived, I waited with the fifty people who had gathered in the church while the monks organized themselves behind the iconostasis. Suddenly, one of the brothers came out and handed me a heavy gold robe. “Father Vasilii says that you can assist.” I did not have time to protest that I, a Protestant theologian, had no business wearing an Orthodox robe. As the other brothers appeared, one handed me a long pole to carry; atop it was an icon of Christ. Together the monks and I processed out of the church, down the steps, along the street, and across the nearby fields to a small spring, where the monastery’s abbot lowered his cross into a well and blessed the waters.

Celebration of Theophany along a river near the Pafnutii-Borovsk

Monastery (with permission of Father Makarii Komogorov)

When we had finished, Father Vasilii invited me to join him and the brothers in dipping into a pool fed by the spring. Air temperatures were in the low teens, but something about the moment swept me up beyond immediate time and space. I stripped and plunged—but just one time, not three (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit)—into the body-numbing waters. As I was drying off afterward—the droplets of water were quickly turning to crystals of ice on my bare skin—two of the young monks exclaimed, “Now you are truly Orthodox!”

Yes, it is true, I have experienced on my own body the power of Orthodox symbols, narratives, and rituals. I have joined thousands of Russian pilgrims surging through the courtyards of the Holy Trinity–St. Sergius Monastery on a holy day; stood with a handful of monks through a long summer night in one of Solovki’s wooden churches—as dusk turned to dawn but dark never fell—wrapping myself in the chanting of the All-Night Vigils; lined up to venerate the incorruptible bodies of St. Aleksandr of Svirsk and St. Ioasaf of Belgorod; faithfully attended the Sunday liturgy in the Church of Sophia, the Wisdom of God; strictly observed the Church’s fasts; climbed the long, steep hill to glorious Easter morning; and passed through the frigid waters of Theophany. I have been—and have not been—“Orthodox” in many different ways, and each has given me a glimpse of heaven on earth.

Moreover, after a decade among Russian Orthodox believers, I have learned to pay more attention to ways in which Christianity has shaped—and will continue to shape—not only their nation but also Western societies for the better.40 “Christian America” or even “Judeo-Christian America” is no less problematic a proposition than Holy Rus’. But American commitments to justice and freedom are arguably fruits of the nation’s deep Christian heritage. Re-Christianization is a misleading term, but the effort to remind a nation of those Christian ideals that have embedded themselves in it may be a valid enterprise if it means not imposing a sectarian ideology on those who believe differently or not at all, but rather the effort to ground in everyday life a vision of the divine transfiguration of a people and place—the hope for a more just and beautiful world even within the real limitations of a particular society.

And yet . . . as much as I have entered into Russia and its Church, I finally decided not to venerate the Virgin’s Belt during those cool, wet November days in Moscow. I could not overcome my nagging doubts that Holy Rus’ could ever really include me. As much as I love and respect Russian Orthodoxy, I am still an American and a Protestant theologian. The social vision and program of the Russian Orthodox Church contrast dramatically with my assumptions about the separation of Church and state, the limited place of the Church in pluralistic societies, and the rightful “secularization” of the physical and cultural landscape. I agree with those North American theologians who argue that social privilege and cultural dominance too often cause churches to neglect their first task, which is to call people to a distinctive way of life shaped by the gospel, not general social norms. And I believe that the Russian Orthodox Church would benefit by attending to these insights.

My questions about Holy Rus’ haunt not only me as an outsider but also a new generation of Russians who relate to religion and society so differently from many of the Church’s hierarchs. These young Russians have never known Communism, only President Putin. They have enjoyed access to the Internet and travel to the West—and seen a people’s revolution in Ukraine. They have gotten used to a steady rise in their standard of living but now worry that the future will bring political and economic insecurity. And while all of their lives they have heard that they are Orthodox, they struggle—like young people everywhere—to know who they really are and where they fit. Will re-Christianization make sense to them, or will they seek a different kind of Orthodox Russia?

Late one evening, Pavel knocks on the door of the dormitory room at a small seminary where my wife and I have been staying, a few hundred miles outside Moscow. He shyly asks if he can invite us up for a cup of tea. In his simple, sparsely furnished room, we take the two available chairs while he sits on the bed. Pavel hopes to become a priest, but he also wants to marry, and the Church will not allow a priest to marry after he is ordained. So far, he admits, he has no marriage prospects in sight. He is working on a master’s degree in Church history but confesses that he lacks motivation. His salary at the seminary amounts to $130 a month, a pittance even in Russia, and he is thankful that he does not have to pay for room and board. His cat recently escaped and has not returned. We talk a little about America, and then he takes out his guitar, and as he plays, he squeezes his eyes together and his soft voice takes on an edge of urgency. “They call Rus’ holy,” he sings.41 And for a moment, he sweeps us up into a magical world of vast forests and endless steppes, big skies and deep lakes, and bleached white monastery walls and tolling church bells.

A few days later, I sit with Dmitrii and Sophia, two young friends in St. Petersburg who are just beginning adult life. They have scraped together enough money to rent a small apartment in a new high-rise on the outskirts of the city, and six months ago Sophia gave birth to Ivan, their first child. Dmitrii studied theology at one of the country’s premier Orthodox institutions but now works for a technology startup. “I was a pious believer when I began my studies,” he says, “but ironically my Orthodox university taught me to think for myself.” When Sophia speaks of her education in Orthodox primary and secondary schools, she is only bitter: “They constantly berated us for not being religious enough.” Today Dmitrii and Sophia are more apt to read Deacon Andrei Kuraev’s blog than attend church.42 They say that he is one of the few independent voices in the Church—and they sadly note that he himself has been pushed to its margins. “How can you name your book Holy Rus’, they ask, “when you see the Church’s obsession with power and control?”

As we take our seats at a small table in their kitchen, I change the subject. What will their life be like now with a son? What are their hopes for him? When they tell me that they are planning to have him baptized on Sunday, I cannot contain my astonishment. “But that makes no sense to me,” I finally blurt out. “Why baptize him if you aren’t committed to the Orthodox Church?” Calmly but firmly, they respond, “Because we want him to know who he is, where he comes from. When we walk into a church or stand during the Divine Liturgy, when we look at the icons and hear the choir’s chanting, when we make pilgrimage to a great monastery or a holy spring, something ineffable touches us—something that should be a part of his life, too. It’s not about the Church. No, it’s about goodness and love, beauty and justice.” Sophia graciously offers me another cup of tea, and I look at Ivan—so tiny, so miraculous—and silently ponder their words.