BERLIN 1897-1900

The Turning Point

My Weimar period ended when I was thirty-six. Already a year before this a profound change had begun to manifest itself in my way of thinking. At the time of my departure from Weimar it became a conscious experience. It was quite independent of the change in my circumstances, great though this was.

Throughout childhood and youth, throughout the Vienna and Weimar periods, Steiner was dogged by the same difficulty: that he could not experience the natural world with the same intensity as he did the ideal and the spiritual world. Whereas the life of the mind was an open book to him, and whereas he lived in his mind in a state of the highest alertness, in the natural world of shapes, colours, and sounds he was as it were a dreamer. Rudolf Steiner at first lacked the very thing that distinguishes a ‘modern’ youth who has grown up in the city streets: the over-alertness of the senses.

I experienced the greatest difficulty in observing and taking in the natural world. It was as though I was unable to infuse the mental experience into the organs of sense with sufficient energy to make what they experienced entirely one with my mind. From the beginning of my thirty-sixth year, all this changed completely. I found myself able to observe the objects, beings, and processes of the physical world with increased accuracy and penetration.

... There awoke in my mind an awareness of sensory objects that had never been there before.

He was aware that in the natural way this ‘mental turning point’ is completed, gradually and organically, in childhood. What distinguishes Rudolf Steiner’s development is that he did not undergo this process until much later in life. As far as concerned his relation to the external world he remained a child for longer. Having experienced this change so much later in life, it was in a state of full consciousness that he experienced it, and this was the positive aspect of such a late development.

I observed that because people make the change from psychic activity in the spiritual world to the experience of the physical world at an early age, they end without fully grasping either the spiritual or the physical world. They instinctively intermingle the messages that objects convey to their senses with what the psyche experiences through the mind, which they then in part make use of in order to represent objects to themselves.

It is difficult to imagine what this ‘mental turning point’ must have been like. In a relatively short time the natural world, which until then had seemed to Steiner as if shrouded in mist, became revealed to him with a clarity and distinctness such as he had never before experienced. The mist dispersed, and the external world in all its colours and outlines lay before him, bathed in sunlight. ‘The precision with which I was now able to observe sensory objects, and the way they penetrated my consciousness, opened up a new world for me.’

Obviously, his new relationship to the world around him reacted on Steiner’s inner world. His mental life was given a boost, the main effect of which was seen in his relations with his fellow human beings:

My powers of observation were directed towards observing, entirely objectively and as an object of contemplation, life as people live it. I scrupulously avoided criticising what people did, or allowing sympathy or antipathy to influence my relationship with them; my aim was simply to experience the effect on me of man as he is. I soon discovered that this kind of observation of the world leads us into the realms of the spirit.

Only now did he feel that he was living in a world that was complete, and that he could move at will between his inner world and the external world. He now saw that ‘true understanding of life’ consists in experiencing the polarity of the internal and the external world, being aware of both these worlds with an equal degree of consciousness, and maintaining the balance between them. This is how he describes his new situation:

This is a world full of enigmas. Knowledge seeks to reach the solution. But in most instances an attempt is made to pass off the thinking about a riddle as constituting its solution. But thinking does not solve problems. Thinking puts the mind on the right road to the solution. But the solution does not lie there.

... And so I told myself: the whole world, man apart, is an enigma, the enigma of the world; and man himself is the solution.

In many respects, the intellectual life of Berlin in 1897 was stratified. The imperial era of Wilhelm II had arrived. Wilhelm II had dismissed Bismarck, who was in retirement on his estates at Sachsenwald. But the great age of Alexander von Humboldt, Hegel, and Schleiermacher was still to some extent making its influence felt. No less a man than Herman Grimm, who was prominent in the activities of the Goethe-and-Schiller Archives at Weimar, occupied a chair at the university. It was an obvious step for Steiner to turn to Herman Grimm and through him seek the entrée to academic circles in Berlin. In Herman Grimm he made the acquaintance of that personality among the students of Goethe—Schröer apart—whose own life and fortunes were a reminder of the great classical period of Weimar. Herman Grimm was married to Gisela von Arnim, the daughter of that Bettina von Arnim who, through Goethe’s Correspondence with a Child, formed the link between all students of Goethe and Goethe’s intimate circle. Rudolf Steiner saw in Herman Grimm ‘as it were an intellectual descendant of Goethe’, and naturally revered him. At Weimar, he recalls, he had often felt that ‘Intellectual distinction entered the Archives with Herman Grimm whenever he appeared there. From the time when, still in Vienna, I read his work on Goethe, I felt myself powerfully attracted to the mind of this man.’ This is understandable, for Herman Grimm was like the last evening rays of sunlight from that heyday of the world of Goethe, a world which by the end of the nineteenth century was otherwise as good as dead. ‘Whenever Herman Grimm was at the Archives, it seemed as if hidden threads led back from them to Goethe.’

Nothing could have been more natural for Steiner than that, being in Berlin, he should seek to attach himself to him as much as possible and through him to share in the official intellectual life of Berlin. Herman Grimm would assuredly have been of great assistance to him. But this was the very thing that Steiner willed himself not to do.

While Steiner was still at Weimar, Herman Grimm, in a communicative mood that was rare for him, when they were lunching alone together at a hotel, expounded his thoughts on the ‘history of the German imagination’. This discourse made a powerful impression upon Steiner, but he was at once aware of the abyss that separated him from Herman Grimm:

I believed that I understood how supernatural spirituality works through men. The mind of this man was able to glimpse the creative spirit, but had no desire to apprehend its intrinsic life, remaining rather in that region where what is spiritual is experienced as imagination.

Goethe’s aversion to ‘thinking about thinking’, to exploring the objective nature of the thoughts and ideas that present themselves in the subjective arena of the human mind, was shared in an equal measure by Herman Grimm. Thus it was that Rudolf Steiner—not without an inner struggle—sought to ally himself to a quite different circle.

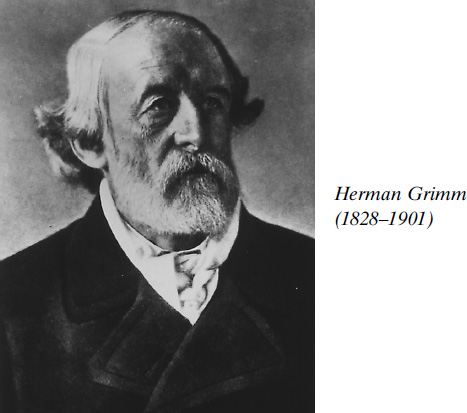

Since 1832, the year of Goethe’s death, a ‘literary magazine’ had been appearing in Berlin under a variety of names and with a variety of publishers. Rudolf Steiner purchased this magazine. One of the conditions of purchase was that he should co-opt Otto Erich Hartleben as joint editor. Rudolf Steiner accepted this obligation, which did not in all respects make his task easier, as a ‘decree of fate’. Principally for economic reasons, the Magazin für Litteratur at the same time became the organ of the Freie Literarische Gesellschaft (Independent Literary Society), the revolutionary antagonist of the traditional Literarische Gesellschaft.

This was the human setting in which Rudolf Steiner now found himself at the age of thirty-six. The inner ‘change’ of the Weimar period now extended itself to his external life, giving it a new direction which could not have been more radically opposed to that of the Vienna and Weimar periods. Steiner chose for his new social world, not the formidable faculty of the University of Berlin, but the avant-garde of the Bohemians, whose like the capital of the German Empire had never seen.

It was as though he wished to put it to the test, whether his abundant inner life could withstand the most violent disruptive stresses to which life in this world would subject it. Shortly before his death he harked back to those ‘Years of Trial’ in Berlin.

The period from my departure from Weimar—1897—to the completion of my book Christianity as Mystical Fact—1902—is filled with this trial. Such trials are the obstacles decreed by fate (karma) which spiritual development has to surmount.

In an essay entitled ‘Personalities in Rudolf Steiner’s Berlin Circle Before the Turn of the Century’, Emil Bock attempts by means of individual character sketches to convey the atmosphere of Rudolf Steiner’s life at that time.

‘...The sedate, cultivated bourgeoisie viewed with extreme moral indignation the circle that surrounded Otto Erich Hartleben. Anyone who frequented that circle was definitely not salon material. And so Rudolf Steiner had to choose between the two circles. Although he gave offence all round by doing so, he joined the odd men out, eccentrics, idlers, night owls, and outsiders of society. But life there was truly colourful, there was bustle and activity. To illustrate the style that reigned there, I will begin with a small anecdote: Otto Erich Hartleben was not fond of staying at home of an evening. But neither, when he was sitting around in his boozers, was he very enthusiastic about going home. It was always broad daylight before he set out for home. It was small wonder that he did not get out of bed until the afternoon. One morning he was making his way through the Tiergarten as usual. There was someone lying asleep on a bench. Hartleben studied him carefully and saw that it was a good friend of his, the poet Peter Hille. He went up to him, shook him awake, and said: “Peter, this won’t do, camping out in the Tiergarten in the damp. You have still so much to give humanity. Now, do go and find yourself a room.” When Peter had roused himself, off the two of them trotted. They had to wait for full daylight, and until then they whiled away their time in a cafe frequented by night cabmen. When the house doors had been opened the two of them went from house to house in the quarter around the Nollendorfplatz, looking for a cheap room. After a long search they found a room on the 5th floor of a house, and already Peter Hille was dreaming of editing a journal of world renown from here. He wanted to be off at once to fetch the bag which contained his collected works on scraps of paper and which he had left with some friends. Otto Erich paid two months’ rent in advance. Both were happy: Otto Erich had done a good deed and Peter Hille had the opportunity at least for a time to lead a regular life. Next morning, at about the same time, Hartleben was walking the same way through the Tiergarten. The only difference was that it was raining. Peter Hille was lying on the bench, just as he had been the day before. Hartleben was furious and gave him a piece of his mind. Peter Hille asked him: “Look, have you got the address?” And Hartleben had to admit that he had forgotten it too.’

It would be wrong to conclude from such anecdotes that this circle consisted entirely of unfortunate beings who had come to grief in the world. The genius of many of those who gathered in this Berlin circle about the turn of the century far outweighed the human weaknesses. Otto Erich Hartleben and Peter Hille, and many others besides, were well above average. Rudolf Steiner developed a particularly cordial relationship with the poet Ludwig Jacobowski, the founder of the association known as ‘Die Kommenden’ (‘The Coming Generation’). In this circle, young artists read their first compositions. Lectures on many subjects made these gatherings a source of knowledge. Steiner frequently played a part. The discussions which followed gave the audiences a deeper insight into the subject matter.

The evening ended with unconstrained social interaction. Ludwig Jacobowski was the centre of the constantly expanding circle. Everyone loved this amiable personality, who was so fertile in ideas, and who in this company disclosed a rich vein of cultivated humour ... This was a personality whose soul was rooted in inner tragedy.

On 2 December 1900, three months after Nietzsche (who died on 25 August), Jacobowski died at the age of thirty of meningitis. Steiner was deeply affected. He undertook the task of reciting the funeral oration for his friend, and thereafter acted as trustee of his literary remains.

Rudolf Steiner contracted a particularly close friendship with another outstanding personality: John Henry Mackay, Scottish born but since 1898 ‘Berliner by choice’. To the cultivated citizens of the capital of the Empire Mackay was a disturbing phenomenon. He had written a novel The Anarchists, edited the works of the controversial ‘individualist’ Stirner, and defended with the utmost conviction his philosophy of life, for which he coined the term ‘individualistic anarchism’. Reason enough for many people to regard him with the gravest suspicion. Steiner had made his acquaintance while still at Weimar—and had found him ‘a thoroughly congenial personality’, whom he learned to esteem.

Around Mackay there was an aura of a wider world. ‘Externally and internally, his demeanour bespoke experience of the world. He had spent periods in England and in America. All this was tinged with his boundless amiability.’

There may have been a passing phase during which Steiner assumed that the resemblance between his own exposition of ethical individualism in his Philosophy of Freedom and Mackay’s individualistic anarchism was closer than it really was. However that may be, this period of friendship with Mackay was likewise the period of his decided and aggressive assertion of the absolute autonomy of the free man and his absolute rejection of all external authority. In this period he was spiritually in jeopardy:

About that time, around 1898, this purely ethical individualism had as it were dragged my soul down into an abyss. Something that was purely and intrinsically human was about to become externalised. The esoteric was about to be turned aside into the exoteric.

Steiner overcame this very real temptation, one might almost say this spiritual trial. His subsequent career proves this once and for all. Reading what he wrote about his friend John Henry Mackay, we have the feeling that we are observing Steiner’s own spiritual struggle:

Mackay’s refined perceptions derived from the fundamental sense of the enormous responsibility of the personality to itself. Meek, submissive natures seek for a Godhead, an ideal that they can revere and worship. They are unable to abrogate worth to themselves and look to something outside themselves to confer it upon them. Proud natures only acknowledge in themselves that which they have created out of themselves ... They are therefore sensitive to all external interference with their lives. Their ego seeks to build its own world, in which it can develop without hindrance. It is only through this reverence for his own personality that a man comes to esteem the ego in others. Mackay’s is a superior, self-confident nature. And he who with such earnestness plumbs the depths of his own soul is stirred by passions and desires of which he who knows not freedom can form no conception...

These words could only have been written by one who had himself gazed into those depths.

John Mackay was a witness when on 31 October 1899 at the Registrar’s Office at Berlin-Friedenau ‘the friendship with Anna Eunike culminated in a civil marriage’. Anna Eunike had moved to Berlin already before Steiner left Weimar. When he followed her shortly afterwards, he first of all took a place of his own, on Karlsbad, near the Potsdam bridge, but it was only for a short time that he experienced the ‘whole wretched business of living in a place of one’s own’. Thereafter he rejoined the Eunikes.

Statements to the contrary notwithstanding, this marriage never ended in divorce. After several years’ separation from Steiner, Anna Steiner-Eunike died on 19 March 1911. Shortly before her death she told her daughter Wilhelmine: ‘Those years with Rudolf Steiner were the best of my life.’

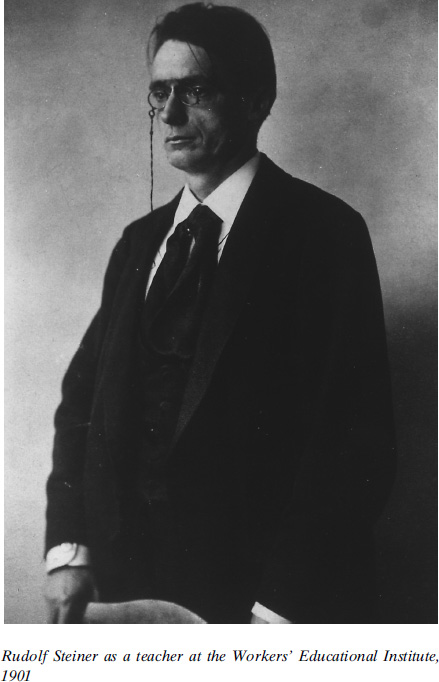

Rudolf Steiner’s life in Berlin was greatly enriched by the teaching work that he undertook at the Arbeiter-Bildungsschule (Workers’ Educational Institute) founded by Wilhelm Liebknecht. With studied indifference to the political aims of the board of governors of this school, he placed his knowledge and his gift for teaching at the service of the school for workers. This was a time when many workers who were seeking for self-improvement were pursuing education and knowledge with enthusiastic resolve. Frequently misinterpreted though it may have been, the slogan ‘Knowledge is power’ nevertheless did epitomize the striving for emancipation of a proletariat eager for human freedom.

It became my noble duty to instruct mature men and women of the working class. For there were few young people among the students. I told the board that if I undertook teaching duties I would teach history according to my own ideas about the development of humanity, not in accordance with the marxist principles currently in vogue in social democratic circles. They still wished for my services as a teacher.

Without thought of self and without identifying himself with the materialistic philosophy of the governors, Steiner gave his services. The subject matter that he taught at this workers’ school ranged from the history of the Middle Ages, the French Revolution, and modern times to the ‘growth of the universe and the social life of animals’ and the ‘anatomy of man’.

There was as yet no eight-hour day or forty-hour week. A working day of 10-12 hours was normal. So much greater was the effort of will made by those proletarians who from 9 to 11 in the evening—often indeed until 12 o’clock—pursued their studies with burning zeal, despite the poorest educational basis imaginable.

Rudolf Steiner, who taught up to five evenings a week, had up to 200 students on some of his courses. In addition, in January 1900 he inaugurated courses in public speaking, at which workers learned to express themselves before gatherings. Emil Bock discovered a document dating from this period which bore the title ‘Grete Lenz, a girl from Berlin’ and which conveys something of the atmosphere of these courses in public speaking.

‘When I heard about the Workers’ Educational Institute I went along to the Engel-Ufer and enrolled. I had intended to read political economy, but I found the subject so boring that one lecture was enough for me. And it must have been very fatiguing, for in front of me and behind me there were a number of workers who had fallen asleep and were snoring so loudly that the lecturer was repeatedly startled and almost came to a stop. I found Rudolf Steiner more inspiring. He taught the working men and women the art of public speaking. Every member of the class was allowed to go up on the platform and speak on some subject, and Dr Steiner corrected the speaker whenever necessary. I was often astonished at how skilfully and correctly those simple people spoke.’

The culminating point of these activities came when on 17 June 1900 Steiner was invited to address as chief speaker a purely working-class audience of 7000 typesetters and printers on the occasion of the Gutenberg Quincentenary in a great Berlin circus. He performed this task—without a loudspeaker!—and was given an enthusiastic reception. Which proves how wrong it would be to think of Rudolf Steiner around 1900 as a ‘withdrawn private tutor’.

Here is how he himself summed up the situation of the working class at that time:

I have the impression that if a larger number of disinterested persons had interested themselves in the working-class movement and had shown understanding for the proletariat, the movement would have taken a quite different course. But the workers were left to live their lives out within their own class while the other classes remained inside their own circles. This was the period in which the upper classes lost their community sense and in which egoism and the wild excesses of the competitive spirit spread far and wide ... Gradually, all communication between the different classes ceased.

Steiner continued his work at this institute until the beginning of 1905. Excessive outside commitments, and intrigues inside the politically motivated board, made it impossible for him to continue to work there.

In these years Steiner associated himself with a totally different circle, the so-called ‘Friedrichshagener’. Bruno Wille, and Haeckel’s friend Wilhelm Bölsche, set the tone here. They founded an ‘independent academy’, in which the liberal theologian Theodor Kappstein played an active part, and the influential ‘Giordano Bruno Federation’—the latter was dominated by a central theme, with which it sought to come to grips: Monism. Different though this circle was from that of the Independent Literary Society, of ‘The Coming Generation’, or of the Workers’ Educational Institute, it is still the same old story. Rudolf Steiner contributes all his powers to the human and spiritual relationships in which he finds himself involved. He plays an active part, meets recognition and opposition, is one of them and yet remains an often welcome guest—and a stranger. For what lies nearest his heart he finds neither understanding nor acceptance.

This brings us to his classical lecture to the Giordano Bruno Federation on 8 October 1902: ‘Monism and Theosophy.’

This lecture acted like a bomb. It was really too much for the good folk who, taking Haeckel’s ‘world enigmas’, had pieced together from it a nice, homespun Monism according to which unity was achieved by the sacrifice of the spiritual wealth of the world. A Monism which gave equal recognition to both the material and the spiritual aspects of the world was over the heads of the majority of his audience. They had not the mental calibre to understand this ‘bombshell’ of an idea. And so once again Rudolf Steiner stood alone in the midst of a circle which was bound to him by ties of human friendship. He had shown his colours, his position was clear. He had knocked at the door, which, once open, was now closed against him. If he was not to lapse into silence, he must find other ways and other people. And he would not, nor could he, remain silent.