THE FOUNDING OF THE CHRISTIAN COMMUNITY (1921-1922)

In the confused times after the First World War the German Protestant Church was in a desperate situation. A group of young theologians and theological students turned to Rudolf Steiner for counsel and help. He had always stressed that he had no wish to become a founder of religions. Anthroposophy, as a spiritual science, is primarily concerned with the quest for knowledge and the discovery of truth, so that anyone can become a member of the Anthroposophical Society, whatever his religion. Defining the relation of his doctrine to the different faiths at Basle in 1917, Steiner stated that:

There is no clash between anthroposophy and any one’s religious faith.

It is impossible to convert anthroposophy directly into religion. But anthroposophy, genuinely understood, will create a genuine, true, unfeigned religious need. For the human soul needs various paths to direct it on the way upwards to its goal. The human soul needs not only the power conferred by knowledge, it must be penetrated by that warmth that comes from the kind of contemplation of the spiritual world that is peculiar to religious faith, to true religious feeling.

In that same year of 1917 Steiner spoke on the same subject in Berlin:

We should never behave as if the quest for spiritual knowledge were a substitute for the practice of religion and the religious life. Spiritual knowledge can greatly sustain religious life and the practice of religion, particularly in regard to the mystery of Christ; but we should be perfectly clear that religious life and the practice of religion within the human community kindles the spiritual consciousness of the soul. If this spiritual consciousness is to come alive in human beings, they cannot remain content with abstract representations of God or Christ but will have to involve themselves again and again in the practice of religion, in religious activity, which for every individual can take on a different form...

The audience that listened to these words included the most eminent preacher of the Protestant Church in Berlin: Dr Friedrich Rittelmeyer, a deeply religious man and at the same time a pastor of souls. In 1916 he had received a call to the ‘New Church’ on the Gendarmenmarkt in Berlin from Nuremberg, where with his friend Dr Christian Geyer he had done great work in proclaiming the message of Jesus Christ within the Protestant Lutheran Church. Both in Nuremberg and in Berlin the churches in which Rittelmeyer preached were always full to overflowing. The bound volumes of the sermons of Geyer and Rittelmeyer, ‘God and the Soul’ and ‘Life from God’, were widely read, and copies were to be found in many protestant homes.

In Berlin, Rittelmeyer had become a member of the Anthroposophical Society. In 1921 he learned of the aspirations of those young theologians who had turned to Rudolf Steiner for counsel and help in the renewal of the religious life of the Christian church. Steiner acceded to their request and invited the theologians to attend two courses; one at Stuttgart at Whitsun and one at Dornach in the autumn.

These courses made a profound impression on all who attended them. To many people’s surprise, Steiner showed himself to be a highly adept and deeply devout theologian, who was not only aware of the ecclesiastical and ritual problems but was also able to advise on them. Thirty years later the Protestant theologian Paul Tillich put into these words what Steiner had expressed: ‘If the sacraments were done away with altogether, religious observance would die and the visible church would cease to exist.’ But whereas Tillich looked sorrowfully on the ‘death of the sacraments’ and observed with resignation: ‘There are no counter-forces in sight, certainly not in theology,’ Steiner gave his assembled theologians detailed arguments in favour of a future sacra-mentalism, without which it would be impossible to build a Christian community. In a mood of deepest earnestness he reminded his hearers of the conditions necessary for such a renewal of the Christian religion, namely that the bearers and proclaimers of the message should themselves be god-inspired and should strive with every fibre of their being to lead ‘a life from God’. Some of the theologians who had gathered round Rudolf Steiner accepted the admonition and the challenge. They gave up their positions and callings and placed themselves at the service of this ‘movement for the renewal of religious life’. At Berlin, Marburg, and Tübingen small groups, mainly composed of students, were soon formed, and dedicated themselves enthusiastically to preparation for the life work that they were to undertake.

One year later, in September 1922, the first congregation of the Christian Community was founded at Dornach, once again with the all-important, unstinting help of Rudolf Steiner. Friedrich Rittelmeyer became its leader, with an entourage of active collaborators, mainly from the younger generation. But a few older members played a part—for instance, Prof. Hermann Beckh, an indologist from the University of Berlin, renowned for his work on Buddhism, the reverend August Pauli, one-time collaborator of Johannes Müller, and Friedrich Rittelmeyer’s brother Heinrich Rittelmeyer, principal of the teachers’ training college at Herford. The theologians were joined by artists, teachers, and leaders of the youth movement. All had heard the call of the discipleship of Christ and had severed their links with their previous occupations. As though inspired by the spirit of the first Pentecost, these founders of the priesthood of the Christian Community believed that their mission was to all nations and all mankind.

The new priesthood of the Christian Community administers the Seven Sacraments in obedience to the ‘Johannine Church’, in the sense given to this term by Schelling and Novalis—there being no Petrine succession—rejecting all dogma and leaving the pastors free to teach and the members of the Community free to believe according to their consciences. For the first time in the history of the Christian church, in the Christian Community women as well as men serve at the altar.

The fact that the Christian Community was founded with the help of Rudolf Steiner has been a frequent cause of misunderstanding. It was never the intention to add a ‘religious wing’ to anthroposophy and the Anthroposophical Society. To believe this is to misunderstand both anthroposophy and the Christian Community. According to its premisses, anthroposophy is intended to be concerned with the perception of spiritual knowledge, and, if it is to be, and to remain, in the fullest sense human, the religious element must be immanent in it. The Christian Community thinks of itself as a member of the invisible Church of Christ which from its beginnings in Jerusalem and beside the Sea of Galilee has made its way in visible form for almost two thousand years via Byzantium, Rome, Geneva, Zürich, and Wittenberg, traversing the world. Though to outward appearances firmly established, this church, after passing through many transformations and reappearing in many different forms became secularized in the nineteenth century by enlightenment and liberalism. This led to the debasement of the primeval Christian impulses. Dogmatism and orthodoxy played their part in bringing about this decline.

But whereas all the other Christian churches and communities in their internal crises have up to the present been conscious of Rudolf Steiner’s life work as at the most a disturbing element breaking in upon their own ordered way of life, to the founders of the Christian Community Steiner’s insight is precisely the spiritual help needed in the age of natural science if the Church of Christ is to survive beyond the modern world.

The Christian Community chose Stuttgart as its administrative centre. Within a few years this ‘movement for the renewal of religious life’ had spread mainly to the larger German cities. But thereafter communities were founded in Switzerland, the Netherlands, England, Austria, Norway, Sweden, and Czechoslovakia. Large communities such as those at Prague, Königsberg, Danzig, Breslau, and Stettin were destroyed in consequence of the Second World War. In 1941 the National Socialists banned the Christian Community in ‘Greater Germany’, the communities were dissolved, their assets were liquidated by the Gestapo, and many of the pastors were imprisoned.

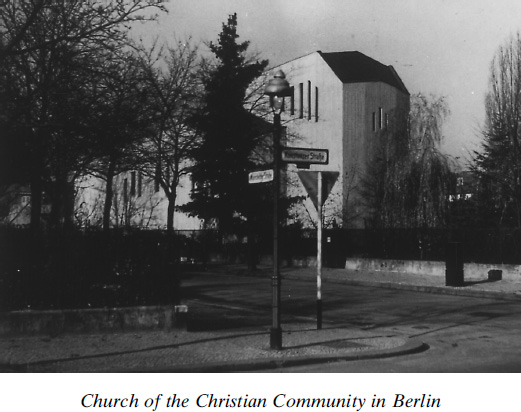

After the war the Christian Community began to grow unobtrusively. In Germany, first rooms were adapted as churches, and later came church buildings. In Berlin at Whitsun 1962 a ‘new church’ of the Christian Community at Berlin-Wilmersdorf was consecrated. It was intended to replace Rittelmeyer’s ‘new church’, which had been destroyed. New communities with their own pastors have since come into being in many parts of the world.