13

American Conquest

American sentiment for the acquisition of far-off California had deep political roots. By the 1820s, Spain’s province was being described in the United States as “a plum ready to be plucked.” Both its rancheros and missionaries resented the arrival of a succession of mostly arrogant Mexican governors who enforced Mexico’s regulations, including unpopular import tariffs. As early as 1829, U.S. President Andrew Jackson sent Anthony Butler as his envoy into Mexico in order to negotiate the potential purchase of California, Texas, and New Mexico. Butler’s arrogant suggestion of a bribe to facilitate U.S. acquisition of the territory deeply offended the Mexicans. Butler returned home in disgrace.

The idea of adding California to U.S. territory, however, was never abandoned by President Jackson, nor by his successors, Van Buren, Tyler, and Polk. Lax Mexican control over California made it plausible that the province might fall into the hands of some European power. The strategic location of San Francisco Bay alone, with its matchless harbor and rich surrounding countryside, greatly increased American enthusiasm for the annexation of California.

Although the Russians had, by 1842, withdrawn from their Fort Ross trading post, leaders of other countries, including even far-off Prussia, had expressed interest in the province. The French, after the exploratory voyages of La Pérouse and Duflot de Mofras, spoke of establishing a protectorate over California. England too coveted control over the province, as well as over Oregon and Texas. James Alexander Forbes, the British Consul at Monterey, suggested to his Foreign Office that California might easily be acquired. The Californians became even more apprehensive at the news that an Irish Catholic priest, Father Eugene McNamara, planned to establish a colony of 1,000 Irish and English Catholics in the San Francisco Bay area. This venture, however, never materialized.

Figure 13.1 John Charles Frémont (1813–1890), known as “The Great Pathfinder,” was a renowned explorer, surveyor, and Civil War general.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (LC-DIG-ppmsca-03210).

Increasing U.S. involvement in California stultified all such foreign plans. The year 1844 saw the election of James K. Polk as President of the United States, an executive who already had committed himself to a popular expansionist policy. He had sent John Slidell, yet another envoy, to Mexico in order to renew negotiations regarding the possibility of purchasing what would become the American Southwest. In California, President Polk relied upon an alert consul at Monterey, Thomas Oliver Larkin, to prepare the groundwork for a peaceful American penetration of the province. On April 15, 1846, following a dispute with Mexico over its border with Texas, President Polk’s administration requested a declaration of war from the U.S. Congress. During the next month, U.S. Army General Zachary Taylor boldly led his troops across the border into Mexico.

Meanwhile, the young explorer Frémont, aware that a war with Mexico over territorial conflicts in the Southwest was possible, had left St. Louis in May 1845 on his third western expedition. Its stated purpose, further exploration of the Great Basin and the Pacific Coast, was hardly likely to relieve tension between the two countries. With a party of 62 soldiers, scouts, topographers, and six Delaware Indians, Frémont again crossed the Sierra crest to Sutter’s Fort, reaching California on December 9, 1845. This time he traveled as far as Monterey, where he held a conference with Consul Thomas Oliver Larkin. José Castro, commander of the garrison at the capital city, was suspicious of the motives that had brought Frémont west. Castro gave the expedition permission to winter in California, with the understanding that Frémont would keep his men away from all coastal settlements.

In early March of 1846, Frémont demonstrated a typical flair for the dramatic. He withdrew toward a bluff named Gavilan, or Hawk’s Peak, where he built a log fortification overlooking the Salinas Valley, only 25 miles from Monterey. Even after a warning from Castro, he raised the American flag, as if to defy his expulsion from the province. At first, Frémont ignored the possibility of trouble. Then the arrival of a warning letter from Consul Larkin, and the realization that Castro seemed to be preparing to dislodge him by force, persuaded Frémont to vacate Hawk’s Peak “slowly and growlingly.” He next moved his men northward toward the wilds of Oregon. Frémont’s rashness embarrassed Larkin and other American residents, who hoped for U.S. annexation of California by quiet, behind-the-scenes contacts. Castro, in particular, was outraged by Fremont’s occupation of Hawk’s Peak.

On their way north, Frémont and his group were overtaken by Lieutenant Archibald Gillespie, a U.S. Marine Corps officer who had crossed through Mexico in disguise. Gillespie produced secret messages from officials in Washington, including Secretary of State James Buchanan, as well as from Frémont’s wife, Jessie Benton, and her father, the bombastic expansionist senator, Thomas Hart Benton. Gillespie’s dispatches probably warned Frémont that war with Mexico was likely and directed him to cooperate with land and naval forces of the United States should a conflict break out. About such a volatile situation, Frémont later wrote: “I was to act, discreetly but positively.” Yet, most historians have strongly criticized his subsequent actions as lacking in either delicacy or tact. His role had suddenly changed from that of explorer to soldier.

As Frémont approached the Marysville (today’s Sutter) Buttes north of Sutter’s Fort, a number of upset Americans flocked into his camp. Believing that Castro had received orders from Mexico City to burn out such American settlers, they formed a group that came to be called the “Bear Flaggers.” These Americans had also heard the rumors of the approaching war between the United States and Mexico. As a member of the U.S. Army’s Topographical Corps of Engineers, Frémont had no instructions to support a revolt among Americans in California. Yet his very presence encouraged a plot to capture General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo at Sonoma. Though Vallejo was a supporter of Americans in California, at dawn on June 14, 1846, a group of “the Bears” smashed their way into his home, rousing the general from his bed, and proceeded to help themselves to his brandy. Their boisterous behavior deeply offended the Vallejo household. “To whom shall we surrender?” asked the general’s wife, unable to comprehend such commotion. After forcing the humiliated general to sign some vague articles of defeat, the Bear Flaggers placed him under arrest. Next they took him to Sutter’s Fort, which further embarrassed its Swiss owner.

Frémont’s role in the Bear Flag Revolt was ambivalent, for he uncharacteristically stayed on the sidelines. It was William Ide, a local American, who led this incipient revolt. His followers hastily fashioned a rough flag with a grizzly bear on it to identify their movement. On the day the Bear Flaggers captured Sonoma, they proudly raised their new red and white banner over its central plaza. On that flag a grizzly bear, California’s fiercest animal, faced toward a red star. Under this image the framers of this crude ensign wrote: “A bear stands his ground always, and as long as the stars shine, we stand for the cause.” They then pronounced existence of a non-existent “California Republic.” The Bear Flaggers would have liked to use the Stars and Stripes as their emblem, but Frémont, although sympathetic to their cause, urged them not to do so.

The Bears next fought one short skirmish with native Californios at the so-called Battle of Olompali. This was a relatively unimportant affair that mainly served to bolster the rebels’ morale. The Bear Flag Revolt, an extra-legal event, came to a sudden halt when U.S. naval forces captured Monterey on July 7, 1846, and raised the American flag. With the Bear Flag movement nullified, Vallejo was at last released from imprisonment at Sutter’s Fort.

Provincial pride and historical romanticism have created the legend that the Bear Flaggers produced an independent California, which then became part of the United States. Actually, this tiny uprising was of limited significance in the acquisition of California. The province’s American conquest would surely have occurred anyway. On July 7, 1846, Commodore John Drake Sloat, commander of U.S. naval forces in Pacific waters, landed 250 marines and seamen at Monterey. A week later, the flag of the United States was flying at Yerba Buena, Sutter’s Fort, Bodega Bay, and Sonoma. In fact, Sloat’s landing prevented any further military actions by independents.

On July 15, Commodore Robert F. Stockton arrived at Monterey on the USS Congress to replace Sloat. Stockton, who threatened to march against “boasting and abusive” dissidents in the interior, was an even more forceful commander than Sloat. Now Stockton issued a proclamation officially organizing Frémont’s volunteers into a unit called the California Battalion of Mounted Riflemen. Although himself a naval officer, Stockton suddenly promoted Frémont to the rank of an army major. Frémont then enlisted volunteers from among local settlers into his new unit. “We simply marched all over California, from Sonoma to San Diego,” wrote John Bidwell, who had joined the battalion, afterward adding: “We tried to find an enemy but could not.” The California Battalion raised the flag unopposed almost everywhere it went. This was possible because Castro’s active forces numbered scarcely 100 men, disaffected and poorly armed. Despite this, the Californio boasted that if the Americans tried to march on Los Angeles “they would find their grave.”

On August 13, 1846, Commodore Stockton’s forces entered Los Angeles. Lieutenant Gillespie, the courier who had met Frémont with messages from Washington, was left in command there with a garrison of 50 men. In enforcing an unrealistic curfew, however, he angered the Angeleños. On September 23, they surrounded his small garrison on a hilltop in the middle of the pueblo. Besieged and short of water, Gillespie, under cover of darkness, secretly sent a messenger named Juan Flaco to Stockton for aid. The dispatch he carried was written on cigarette papers and concealed in his long hair. Pursued for miles by Californio horsemen, Flaco managed to outride them. After Stockton received the message of distress, he sent 350 sailors and marines to relieve Gillespie’s tiny force.

These reinforcements arrived aboard the USS Vandalia under the command of Captain William Mervine, which dropped anchor at San Pedro, outside Los Angeles, on October 7, 1846. Mervine was almost too late, for Gillespie’s hilltop position had become untenable. He had virtually surrendered to the Californios but, following a sort of truce, was allowed to retreat with his men to San Pedro. Upon reaching the port, Gillespie departed by sea. Before leaving, his men buried their casualties on a small island that came to be known as “Dead Man’s Island.”

After U.S. forces landed at San Pedro, a strange skirmish followed. This became known as “The Battle of the Old Woman’s Gun.” On the Dominguez Rancho a number of locals gathered on horseback, armed with sharp willow lances and smooth-bore carbines. Their most damaging weapon, however, was a four-pound cannon, an antique firearm that had been hidden by an old woman during the first American assault on Los Angeles. The cannon was lashed with leather reatas (thongs) to the tongue and wheels of a mud-wagon, which the Californios whipped up and down a hillock, firing the cannon effectively enough to force the Americans to retreat to their ships. Though Lieutenant Gillespie had only narrowly escaped, for a time the territory south of Santa Barbara, including Los Angeles, was again temporarily in the hands of Castro’s Californio forces.

At San Diego, as Commodore Stockton planned to retake Los Angeles, he received an important message that modified the military situation in California: this was a desperate dispatch from General Stephen Watts Kearny. The War Department had ordered Kearny to proceed overland with an “Army of the West” from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to pacify New Mexico and proceed to California to set up a government there. As Kearny moved westward from Santa Fe, he ran into Kit Carson. A celebrated scout, Carson was at the very moment relaying some dispatches from Commodore Stockton eastward to Washington. He mistakenly told General Kearny that the American flag was already flying throughout California.

Not knowing that renewed fighting had broken out near Los Angeles, Kearny sent most of his force back to Santa Fe, himself continuing onward with only 100 dragoons and two small howitzers. This was a grave mistake. Because Carson was such an experienced guide, Kearny ordered him to turn around and return with him westward. The general sent Stockton’s dispatches back to Washington with one of his own scouts, the mountain man Thomas Fitzpatrick.

On December 5, 1846, northeast of San Diego, General Kearny ran into a hornet’s nest. More than 150 armed Californios under Andrés Pico, Pío Pico’s brother, were encamped at San Pascual (near present-day Escondido). During a cold rainstorm, the Californios charged Kearny’s forces. The Americans, their ammunition and powder wet, tried to beat off the onslaught by hand-to-hand combat during which 22 Americans died. Kearny’s tired and bony army mules were no match for the quick California ponies whose riders made deadly use of their sharp willow lances. The Americans, armed with only short sabers, could barely defend themselves against their fleet opponents. The general soon found himself on a hilltop near the San Bernardo Rancho surrounded by hostile forces. With their powder still damp and their supplies dangerously low, Kearny’s tired dragoons subsisted for four days on half-roasted and smelly mule flesh, their water in scant supply. Though exhausted, their spirits soared after the arrival of 200 rescuing sailors and marines that Commodore Stockton had dispatched from San Diego.

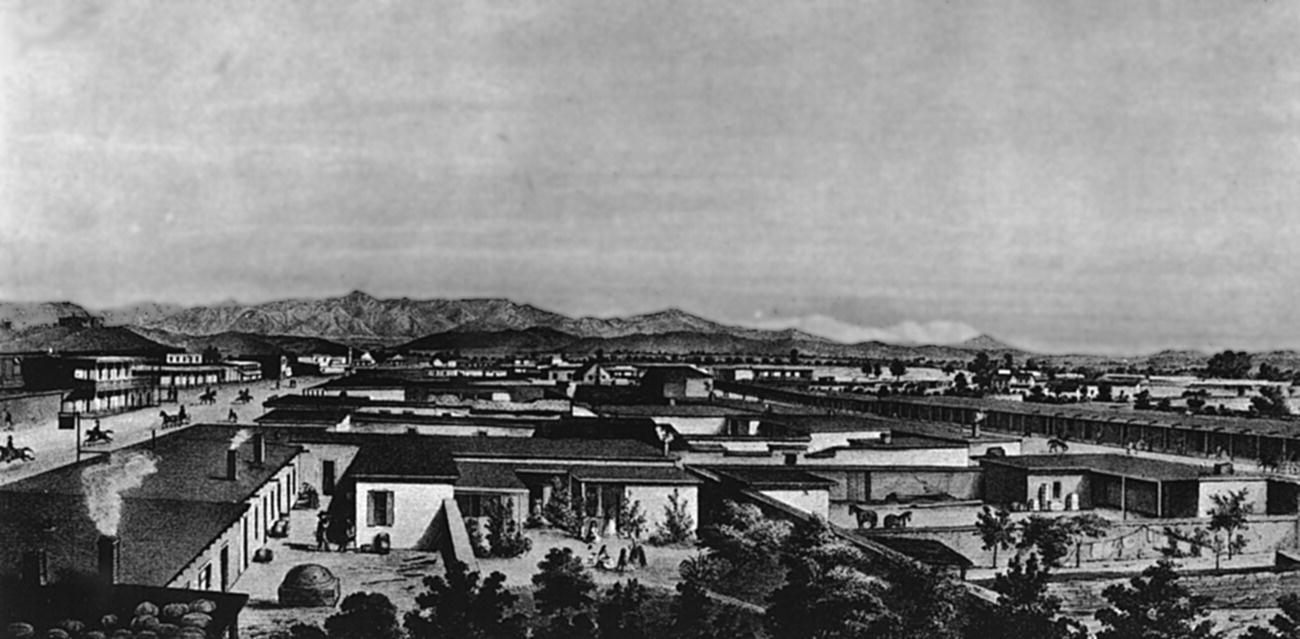

Figure 13.2 Los Angeles, 1857 from a contemporary print.

Courtesy of Andrew Rolle.

General Kearny had suffered a significant defeat at what became known as the Battle of San Pascual. He was grateful indeed that Stockton had relieved his tattered forces. After Pico’s men finally withdrew, Kearny resumed his march toward San Diego. After resting there, the general joined Stockton’s forces on a northward march. With 600 army dragoons, marines, and sailors, they left San Diego to retake Los Angeles. At the same time, Frémont, on his way down the coast from Monterey with 400 volunteers, was also nearing that pueblo. Hoping to enter Los Angeles from the south, Kearny and Stockton met no real opposition until they reached the muddy banks of the San Gabriel River outside Los Angeles. Meanwhile, General José María Flores hoped to surprise the Americans with a final cavalry charge along the northern bank of the river. Nonetheless, Kearny and Stockton succeeded in fording the stream. Several days later, on January 10, 1847, at the Cañada de los Alisos, near the town’s future stockyards, the Americans and the Californios fought a skirmish called the Battle of La Mesa. Although of slight importance, it did confirm the American recapture of Los Angeles. At its plaza, Lieutenant Gillespie joined in the ceremony to hoist the flag he had been compelled to haul down the previous September.

On January 13, 1847, Stockton and Kearny were taken aback when Andrés Pico stated that he would prefer to surrender to Frémont, who had moved into the San Fernando Valley just north of the pueblo. Meanwhile, Pico’s brother, Pío Pico, the last Mexican governor of California, had fled to the Mexican state of Sonora. Frémont, now being called a lieutenant colonel, clearly acted over the head of Kearny, a brigadier general, when he pardoned Andrés Pico and other Californios. The generous peace treaty that Frémont concluded became known as the Cahuenga Capitulation. Somehow, Frémont was considered a fellow Latino by those Californios caught on both sides of the conflict.

An American settler whose loyalties also were split was Isaac Williams, who had married a local girl, Maria de Jesus Lugo. Her father, a land baron, had presented the couple with a 22,000-acre rancho. Williams, by purchase, had added another 13,000 acres to the spread. When this property was attacked, he actually begged for help from Mexican forces. During the nearby battle of Chino, part of his hacienda caught fire. Williams and his children climbed onto the roof, waved a white flag, and begged for mercy. Both the Americans and Mexicans subsequently labeled him a coward, even a traitor to the United States.

Meanwhile, a conflict in orders from the Navy and War Departments had led to a three-way quarrel over which of California’s conquerors commanded the 1,000 or more U.S. servicemen under them at Los Angeles. General Kearny quite rightly considered himself the ranking U.S. commander in California. But Commodore Stockton had confusingly decided to relinquish his authority in favor of Frémont in order to travel back to Washington, D.C. This left General Kearny and Frémont to fight it out over who would govern California. Ultimately, the general prepared court-martial charges against the unbending Frémont. Their animosity toward one another led to a great military trial following the War with Mexico.

That conflict officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848. A new southwestern boundary now gave the United States all of Upper California as well as New Mexico and a greatly enlarged Texas. Residents thereafter had the option of becoming American citizens. The U.S. government agreed to pay Mexico $15 million for land that had already been conquered.

Although the immediate political future of California remained unsettled, its control was no longer in the hands of Latino leaders. Despite having been conquered by “Los Yanquis,” the Hispanic tradition remained so strong that, in some homes, the speaking of English was forbidden. More than a few Californios were never reconciled to being ruled by their American conquerors. But, having finally expanded across the breadth of the continent, the Americans were in California to stay.

Selected Readings

- Regarding the last days of Mexican rule, see George Tays, “Pio Pico’s Correspondence with the Mexican Government, 1846–1848,” California Historical Society Quarterly 13 (March 1934), 99–149. Concerning the acquisition of California, the earliest non-heroic study was Robert G. Cleland, The Early Sentiment for the Annexation of California (1915). See also Paul Bergeron, The Presidency of James K. Polk (1987); Charles Sellers, James K. Polk (2 vols. 1957–1966); Allan Nevins, ed., Polk: The Diary of a President (1929); Robert W. Merry, A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk and the Conquest of the American Continent (2010); and Walter R. Borneman, Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America (2008).

- On Frémont in California, see Allan Nevins, ed., Narratives of Exploration and Adventure (1956) and his Frémont: Pathmarker of the West (1939); Cardinal L. Goodwin, John Charles Frémont: An Exploration of His Career (1930) is dated and strongly negative. For an opposite viewpoint by Frémont’s powerful father-in-law, consult Thomas Hart Benton, Thirty Years’ View (2 vols. 1854–1856). Andrew Rolle, John Charles Frémont: Character as Destiny (1991) is an appraisal of both his strengths and emotional shortcomings. See also Proceedings of the Court Martial in the Trial of (J. C.) Frémont (1848).

- The Bear Flag Revolt appears in Fred B. Rogers, Bear Flag Lieutenant: The Life Story of Henry L. Ford (1951); also see the reprint of Simeon Ide, A Biographical Sketch of William B. Ide (1967). General Kearny’s march westward is detailed in Dwight Clarke, Stephen Watts Kearny, Soldier of the West (1961); William H. Emory, Notes of a Military Reconnaissance (1848); Joseph Warren Revere, A Tour of Duty in California (1849); Arthur Woodward, Lances at San Pascual (1948); and Philip St. George Cooke, The Conquest of New Mexico and California (1878).

- On the War with Mexico, see Neal Harlow, California Conquered: War and Peace in the Pacific, 1846–1850 (1982); Justin H. Smith, The War with Mexico (2 vols. 1919); Glenn W. Price, Origins of the War with Mexico: The Polk–Stockton Intrigue (1967); Edwin A. Sherman, The Life of the Late Rear Admiral John Drake Sloat (1902); Gene A. Smith, Thomas Ap Catesby Jones, Commodore of Manifest Destiny (2000); Samuel Bayard, A Sketch of the Life of Com. Robert F. Stockton (1856); Harlan Hague and David J. Langum, Thomas O. Larkin: A Life of Patriotism and Profit (1990); Fred B. Rogers, Montgomery and the Portsmouth (1959); and Werner H. Marti, Messenger of Destiny: The California Adventures of Archibald H. Gillespie (1960). See also Theodore Grivas, Military Governments in California (1963).