14

Gold

The American conquest of California was soon followed by a world-class event that would forever shape the future of the province. On January 24, 1848, James Wilson Marshall, a Scotsman from New Jersey, was busy supervising some day laborers. An impressive figure, dressed in buckskin and a bright Mexican serape, he ordered them to dig a millrace along some mud flats on the south fork of the American River. His plan was to divert water in order to run Johann Sutter’s new sawmill. The Indians called this location Collomah (today’s Coloma). Marshall recalled that “my eye was caught by something shining in the bottom of the ditch.” He bit into a flake of shining metal. It was soft, even after he hit with a hammer. Instead of fragmenting, the metal flattened out. He gathered up other nugget and flake samples. Back at New Helvetia he and Sutter tested them chemically with Aqua Fortis. This confirmed that they were real gold.

Neither man yet realized that Marshall had discovered a new El Dorado. This was not, however, the first discovery of California gold. Years earlier, some mission Indians had unearthed small quantities of the metal. When they brought the gold to the padres, the friars cautioned them not to divulge the location of their discovery. The missionaries did not want to see the province inundated by money-mad foreigners.

Later, in 1842, along southern California’s San Feliciano Canyon, inland near today’s Newhall, Francisco Lopez, who lived nearby, used a sheath knife to dig up some wild onions. When he pulled the plants from the ground, he noticed bright yellow flakes clinging to their roots. It too was gold. After nearby settlers heard the news, several hundred of them headed up the canyon. The American trader Abel Stearns sent 20 ounces of the metal they brought out from Los Angeles to the Philadelphia mint. Unfortunately, the San Feliciano lode “played out” within only a few months.

Then came the greatest of all gold discoveries. The principal figure in this event was clearly Marshall. Back in 1844, equipped with only a flintlock rifle and training as a coach and wagon builder, he had arrived in California by emigrant train. He bought a small plot of land near Little Butte Creek, where he raised a few cattle and also built and repaired spinning wheels, plows, ox yokes, and carts. In 1846, after participating in a campaign against the Mokelumne Indians, Marshall joined the Bear Flag insurgents. He next enlisted in Frémont’s California Battalion. After the American conquest, Marshall ended up at Sutter’s Fort, “barefooted and in a very sorry plight.” Nearly all his livestock had strayed from his ranch or been stolen. Like many former California combatants, Marshall had received no compensation for his volunteer war services.

Meanwhile, Sutter’s community, clustered around his fort, had experienced an influx of other American settlers. The demand for lumber was increased. Desiring to expand his operations, Sutter had originally sent Marshall out to search for new stands of timber and a suitable location for the saw and flour mill. Then Marshall saw the gold. Once both men realized the enormity of their find, they hoped to keep it a secret, so as not to upset the routine at Sutter’s Fort.

But their discovery was too great, and news of it impossible to contain. Sutter’s diary tells us that, by early March, he quite suddenly lost most of his workmen, who “left for washing and digging gold.” He complained that “they left me sick and lame behind.” His business operations were headed for ruination. Sutter recorded that his Indian workers were “impatient to run” toward the gold streams of the Sierra. An entire year’s wheat crop lay unharvested in his fields. Furthermore, Sutter could find no one to operate his new mill.

Meanwhile, Sam Brannan, the apostate Mormon who had refused to join Brigham Young’s colony in today’s Utah, had become a merchant at Sutter’s Fort. Unwittingly, he would further damage Sutter. Hoping to do business with future miners, Brannan galloped off toward San Francisco, clutching a medicine bottle filled with gold dust and nuggets. As he rode along the unpaved streets of the city he shouted “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!” He swung his hat wildly with one hand and waved the bright gold bottle in the other.

A great human tide surged toward the icy streams of the Sierra in quest of riches. As labor costs along the California coastline soared, local businesses stopped operating. Some 500 sailing vessels soon lay abandoned in San Francisco Bay; both their crews and passengers rushed inland in search of gold. Soldiers too absconded for the gold fields. Amidst all this hysteria, San Francisco’s newspaper, The Californian, suspended publication on May 29, 1848, announcing that most of its subscribers had left town, not bothering to pay their bills for lodging or supplies.

At Monterey, Consul Thomas Oliver Larkin bitterly lamented his town’s depopulation as well. “Every bowl, tray, and warming pan has gone to the mines,” he wrote. Shovels and pick axes were especially hard to find. Walter Colton, a naval chaplain, wrote that “the gold mines have upset all social and domestic arrangements in Monterey. Even the millionaire is obliged to groom his own horse and wheel his own wheelbarrow.”

Within a few months, word of the California gold find reached every part of the globe. Exaggeration of the riches the Sierra held became so feverishly wild that one writer remarked: “A grain of gold taken from the mine became a pennyweight at Panama, an ounce in New York and Boston, and a pound nugget at London.” By May of 1848, gold was being mined at distances of 30 miles surrounding Sutter’s new mill. By June of that year, 2,000 men were busily digging for gold. In another month that figure doubled. The gold seekers of 1848 were but the vanguard of a human avalanche about to descend upon California.

Once President James Polk learned of the gold discovery in newly conquered California, he could not resist inserting the news into a presidential message of December 5, 1848. President Polk’s proclamation that previous “rumors” were indeed true and that large amounts of gold had been found in California set off a rush to San Francisco by land and by sea. California’s population quickly ballooned. At the beginning of 1849 there were, exclusive of Indians, only some 26,000 persons in the province. By the end of that year the number had reached 115,000. Approximately half of the adult residents were engaged in mining. Some 20,000 foreign immigrants arrived, mostly by sea, from all over the world. The Chinese outnumbered any other foreign group. They would become the backbone of California’s labor force.

San Francisco soon became the fastest-growing city in the world. From a population of only 812 in March of 1848, it grew into a boom town of 25,000 people. To process hundreds of small sacks of gold, the San Francisco Mint was established. In 1854, its first year of operation, it minted the rarest of all coins, the $20 double eagle gold proof “S Mint.”

Sacramento’s waterfront, west of Sutter’s Fort, became an agitated debarkation point. Located en route to the mining areas, thousands of adventurers left there for the diggings. The routes the gold seekers took varied. Most Americans who headed west to California took one of three main routes: “around the Horn” of South America; “by way of the Isthmus” of Central America; or overland “across the plains.” The route around Cape Horn took as long as nine months; the actual rounding of the cape being particularly hazardous. Some vessels took weeks to break through the choppy, fogbound Strait of Magellan. Not all of sailing vessels, especially those of light tonnage, were seaworthy. Passengers had to endure both monotony and seasickness. On the Fourth of July, aboard the ship Rising Sun, its crew boisterously celebrated clearing Cape Horn. They blew bugles, played martial music, and recited the Declaration of Independence. After speeches, a special dinner was served consisting of roast goose, plum pudding, mince pies, figs, and assorted nuts.

Because the lack of exercise on board softened up the thousands of travelers who rounded the Horn, this became known as the “whitecollar sea route.” More pointedly, these passengers were often merchants, lawyers, or doctors – not workingmen. Sometimes they were fortunate enough to book a place aboard a ship scheduled to make South American landfalls en route, either at Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Santiago, or Callao.

Others arrived in California by crossing the Isthmus of Panama or Nicaragua. This route was the quickest, if not the most comfortable, of the principal routes. The voyage from New York to the Panama Coast was 2,500 miles; the trip across the Isthmus another 60 miles. This is where travel conditions grew unpleasant, even dangerous. Malarial fever was prevalent in all parts of Central America, as were cholera, dysentery, and yellow fever. Part of the isthmus crossing entailed travel through swamps in long canoes poled or paddled by native boatmen. Some took along a carbine, camping equipment, and a watertight bag in which to stow medicine and clothing. Then these travelers had to go overland, usually on mule back, to reach the Pacific side of the isthmus.

Once there, a shortage of coastal vessels might stretch one’s stay in this unhealthy malaria-plagued location into months. Now came a second ocean trip, 3,500 miles up the Pacific coast to San Francisco Bay. Most of the vessels providing this service offered wretched accommodations. The food was vile and the water supplies often brackish. Pacific Mail Steamship Company ships, powered by steam, began only gradually to supplement service by worm-eaten and leaky sailing vessels.

Even more than the clipper ship or steamer, the covered wagon, or “prairie schooner,” symbolized the vast American population movement during the Gold Rush. The favorite overland trail was a northern route leading west from St. Louis through South Pass in the Rocky Mountains. In the year 1849 alone, 30,000 “forty-niners” used this trail. A southern route proceeded over the Santa Fe Trail, which ran from Westport (later Kansas City). This path followed the Gila River to the Colorado River, finally crossing the desert into southern California.

With luck, the 2,000 miles to the gold fields on overland routes could be covered in 100 days. Fortunate parties might trundle along some 18 miles from sun up to sun down. Caravans included as many as 26 covered wagons. Usually each was drawn by five yoke of oxen or a span of ten mules. Regardless of the number of wagons, every overland group faced dangerous river fordings. Scarce food supplies had to be carefully hoarded, and the wagons guarded against Indian attack. Therefore, delays in the trip were inevitable. A wagon had to be unloaded and reloaded several times in a single day to cross rough terrain and swollen streams. Some travelers, overloaded with household belongings, left stores and farm implements behind on the prairies.

Among the most tragic of all pioneer experiences were those encountered by the comparatively few overlanders whose fate led them into torrid Death Valley, 110 feet below sea level, a “seventy-five mile strip of perdition” across which ferociously hot winds drove the stinging sands. The blinding glare of the sun parched the skin and induced a feverish, half-crazed state.

During 1848 and 1849, a party led by William Lewis Manly from Vermont encountered innumerable delays, making it impossible for them to reach the Sierra in time to avoid the fall snows. Near Salt Lake, Manly’s little band was overjoyed to join forces with another group headed by Asabel Bennett, an acquaintance of Manly. Because it was late in the season, they dreaded facing the same fateful plight of the Donner Party in the Sierra Nevada’s winter snows. The Bennett-Manly group, therefore, decided to take a longer and supposedly safer route into southern California. From there they hoped to travel northward to the gold mines. However, the unfortunate group was soon lost, wandering through a seemingly endless sea of hot sand. In the distance the 13 men, three women, and six children could see the Panamint Mountains, their summits white with snow. Again and again they tried to escape from their camp near Furnace Creek. Although they did find a few brackish water holes, their scarce supplies were fast running out. One after another, their oxen had to be killed for food.

As these pioneers dipped into their last sacks of flour, Bennett proposed that Manly and John Rogers, the strongest of the men, go ahead on foot to seek help. The main party was to await their return from the California settlements with supplies. Manly and his men struck out toward the Panamints. Reaching Walker Pass, they crossed the southern Sierra range. After 14 days, they luckily reached Mission San Fernando.

There they obtained supplies and pack animals. Twenty-six days later, when they finally returned to the desert camp, the remaining survivors were so weak that Manly and Rogers moved within a hundred yards of the wagons without seeing any sign of life. After they fired a rifle shot, one man crawled out from under a wagon. Manly later wrote: “He threw up his arms high over his head and shouted ‘The boys have come! The boys have come!’” But among those huddled under the wagons, Rogers and Manly found only a few survivors. One of them, Mrs. Bennett, “fell down on her knees and clung to me like a maniac,” Manly recorded.

Figure 14.1 The Devil’s Golf Course is what remains of Death Valley’s last lake, which disappeared over 2,000 years ago. The terrain is formed as water rises up through underlying mud and evaporates, leaving pinnacles of salt behind. Devil’s Golf Course, Death Valley, California.

© Terry Ryder | Dreamstime.com.

At the beginning of February in 1850, the little band finally escaped from the appropriately named Death Valley. Abandoning their wagons and most of their remaining equipment, they crept along the eastern Sierra slope. They moved through Red Rock Canyon and crossed the bed of the shallow Mojave River. By the time the bedraggled group finally reached Rancho San Francisco in southern California, they had spent an entire year on their journey west, yet they were still more than 500 miles from the mines! Their story, as told by Manly in his book, Death Valley in ’49, remains a classic account of western history.

California’s placer camps, however, hardly resembled the paradise envisioned by gold seekers. Mining was dirty, strenuous work, and comforts and conveniences in the field were practically nonexistent. Most “claims” lay along the banks of streams, where thousands of persons crowded in trying to strike “pay dirt.” Miners worked both “dry diggings” in flats and gullies and “wet diggings” along sand bars or swift streambeds. In either case, the chances of finding a rivulet laden with gold-bearing gravels were relatively slim.

For washing gold ore, panning was the simplest method. The sifting pan was made of tin or sheet iron, with a flat bottom and sides angled at 45 degrees. The lonely prospector, gold pan in hand, his meager supplies loaded on the back of a donkey, became symbolic of the Gold Rush. But miners brought a variety of gadgets with them. Some utilized the “Long Tom,” or “Rocker,” an elongated wooden trough much easier to use than a simple pan. The most effective mining involved the use of elaborate sluice and waterwheel systems, including “flumes,” or open ditches constructed of boards, and later of iron pipe. Lighter gravel running through the chutes was washed away by the action of stream water. With luck, the heavier gold was captured, then dried out and bagged in tiny cotton sacks.

California’s principal ore-bearing region, known as the Mother Lode, was divided into the Northern and the Southern Mines. This area spanned 70 miles from Mariposa on the south to Amador on the north. The northern mines included the American River and its forks, as well as the Cosumnes, the Bear, the Yuba, and the Feather Rivers. Sacramento was the chief depot for provisioning the north. The Southern Mines, with Stockton as its headquarters, included camps lying below the Mokelumne River and the Calaveras, the Stanislaus, the Tuolomne, the Merced, and mountainous portions of the mighty San Joaquin.

Picturesque place names were applied to makeshift towns that mushroomed in the mining regions. These included Git-up-and-Git, Lazy Man’s Canyon, Wildcat Bar, Skunk Gulch, Gospel Swamp, Whisky Bar, Shinbone Peak, Humpback Slide, Bogus Thunder, Hell’s Delight, Poker Flat, Ground Hog Glory, Delirium Tremens, Murderers Bar, Hangtown (later Placerville), and Agua Fria (cold water). Hangtown was so named because of a lynching there in 1849.

Miners lived a rough-and-tumble life. As long as a lode held out, those at the mining camps knew few restraints. Nevertheless, charges of claim jumping have been greatly exaggerated, as has the lawlessness of life in the diggings. Most prospectors were law-abiding. While they awaited the arrival of a regular legal system, the miners drew up “district rules,” which they themselves enforced. The miners judged criminal offenses individually before makeshift courts, which meted out such penalties as ear cropping, whipping, branding, and even hanging. This extralegal justice involved some abuses, but it discouraged crime. This was the beginning of vigilantism.

The ratio of men to women in the gold fields was approximately 20 to one. Within six months after arrival, one-fifth of the men were dead. Some perished because of laboring in the frigid waters and due to deplorable sanitary conditions in the mining camps and shanty towns. Others died as the result of too much liquor or via homicidal disputes. In this predominantly male society, prostitutes were in great demand.

Despite the rowdy environment, miners practiced a certain fellowship in their tents and crude dugouts. Sundays were both a day of rest and the day on which one did the week’s washing, baking, or mending. Those with wives and children back home wrote letters. Idle time was enlivened by swapping yarns or drinking and gambling.

The bleak days that prospectors spent grubbing for wealth made them especially appreciative of traveling performers who stopped in many a mining town. Prominent among them were Lotta Crabtree, Edwin Booth, and the internationally popular Lola Montez. A more frequent means of entertainment for lonesome men was singing in groups from a booklet entitled Put’s California Songster. The lyrics of mining-camp songs were usually set to such well-known airs as “Pop Goes the Weasel,” or “Ben Bolt.”

Figure 14.2 “A Sunday’s Amusement in the Mines,” 1848–1849, from a contemporary print. Robert B. Honeyman, Jr. Collection of Early Californian and Western American Pictorial Material, courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

No song equaled “The California Emigrant” in popularity. Its chorus was set to the tune of “Oh! Susannah!”

Oh! California!

That’s the land for me,

I’m going to Sacramento

With my washbowl on my knee!

A naughtier air, sung to the tune of “New York Gals,” was retitled “Hangtown Gals”:

Hangtown gals are plump and rosy,

Hair in ringlets mighty cosy;

Painted cheeks and gassy bonnets;

Touch them and they’ll sting like hornets.

CHORUS

Hangtown gals are lovely creatures,

Think they’ll marry Mormon preachers

Heads thrown back to show their features.

Ha, ha, ha! Hangtown gals.

They’re dreadful shy of forty-niners,

Turn their noses up at miners;

Shocked to hear them say “gol durn it.”

Try to blush, but cannot come it!

CHORUS

Hangtown gals are lovely creatures. [repeated]

Pioneer women were only occasionally acclaimed, as in the song “Sweet Betsy From Pike”:

They swam the wide rivers and crossed the tall peaks,

And camped on the prairie for weeks upon weeks.

Starvation and cholera and hard work and slaughter,

They reached California, spite hell and high water.

Sarah Royce was one of these frontier women. Highly literate, this mother of future Harvard philosopher Josiah Royce, encountered a hard and scarcely rewarding life in the Far West. In 1849, another pioneer was Mary Bennett Ritter, one of the first physicians and probably the first American woman to come to California via Panama. She recalled that when she arrived, “there were from ten to forty men to be cooked for, beside the general housework, the washing and ironing, the churning, bread making and sewing for four children – plus making my father’s shirts and underwear.” Ritter and her mother heated the water for Saturday night baths and made their own soap and candles.

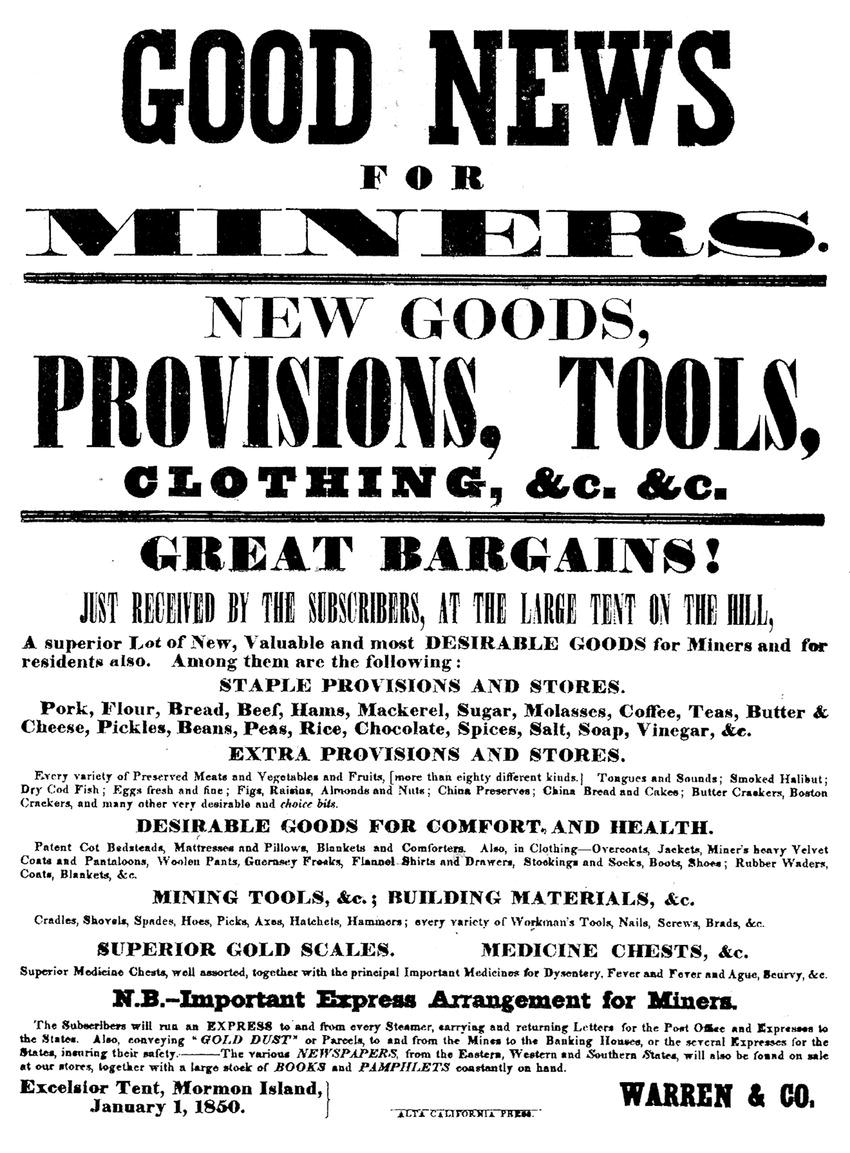

Figure 14.3 Broadside advertisement of the Mormon Island Emporium in the California mines, 1848–1849. Such stores also served as mail, express, and banking centers.

Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

All these workaday chores gave rise to yet another song about women:

There’s too much of worriment that goes in a bonnet.

There’s too much of ironing that goes in a shirt.

There’s nothing that pays for the time you waste on it.

A woman’s view of the gold rush was far different from that of men. Sarah Haight, seeing the environmental damage wrought by mining, wrote in her diary: “How unsightly it makes the country appear. How few flowers and how little vegetation there is where there is gold … How often its blighting effects are on the human heart.”

The small savings of most miners were quickly used up. Each was lucky if he earned $100 in a month. This was a skimpy return for the extreme hardships and high cost of staying healthy amid the dampness. Occasionally a miner struck it rich. One man scooped up two and a half pounds of gold in only 15 minutes, which he sold for $16 per ounce.

Due to the gold boom, however, consumer prices in northern California were fantastically high as compared to those in the eastern United States, where money had many times today’s purchasing power. In San Francisco, copies of eastern newspapers were grabbed up at $1 apiece. A loaf of bread, which cost 4 or 5 cents on the Atlantic seaboard, sold for 50 or 75 cents. Kentucky bourbon whiskey leaped to $30 a quart; apples sold for $1 to $5 apiece, eggs for $50 a dozen (one boiled egg in a restaurant cost as much as $5), and coffee for $5 a pound. Sacramento merchants sold butcher knives for $30 each, blankets for $40, boots for $100 a pair, and tacks to nail flapping canvas tents for as much as $192 a pound. Medicine cost $10 a pill, or $1 a drop. In Stockton or Sacramento, a hotel room cost as much as $1,000 per month, then a tremendous sum back home.

Heaps of gold dust, usually stored in doeskin bags, piled up in San Francisco’s safes. The eastern journalist Bayard Taylor complained: “You enter a shop to buy something; the owner eyes you with a perfect indifference. If you object to the price, you are at liberty to leave, for you need not expect to get it cheaper; he evidently cares little if you buy it or not.” The merchant firm of Mellus and Howard was “so surrounded with piles of gold dust and receiving such enormous rents from their landed property … that they consider 10 to 12 thousand dollars for discharging a ship a mere flea bite.”

By the early 1850s, much of the loose ore had been panned out of California’s stream beds. Miners who had lost their grubstakes headed back home. No longer could penniless diggers hope to wrest fortunes from California’s rocks and cliffs with only a few simple tools and the sweat of their brow. Henceforth, technological innovations for more complex mining operations required heavy capital. The technique known as hydraulicking involved the use of canvas hoses and nozzles to wash away topsoil, making gold particles more accessible. Whole rivers were diverted and canyons stripped bare. In time, hundreds of miles of canals and flumes carried water through iron pipes to devices that could extract gold. Stamp mills then reduced tons of rock to powder ore. The days of pick, shovel, pan, and burro were clearly over. Now it was mining companies, rather than individual miners, who tunneled their way through bedrock.

Once the “easy pickings” drew to a close by the middle of the 1850s, discouraged prospectors left makeshift ghost towns behind and flocked into the cities, anxious to find any sort of work. Traveling theater troupes that had been able to charge as much as $55 for stall seats now played to almost empty houses. Merchants found it difficult to sell the expensive “Long Nine” Havana cigars that had commanded high prices in boom days. In San Francisco and Sacramento, shopkeepers threw sacks of spoiled flour into the streets to help fill muddy holes; unsaleable cast-iron cookstoves were dismantled, their plates used as sidewalks. No longer did miners send out their laundry as far as Hawaii and even China.

A few of those who stayed on in California bought farm land that quickly rose in price. These lucky persons, including none other than John Bidwell, amassed the fortunes that had eluded them in the placers. Henry Mayo Newhall, who started out as an auctioneer on the San Francisco waterfront, bought up a number of ranches. He went on to found a great land company.

One of the worst results of the gold rush was despoliation of the natural environment. Miners had removed over 750,000 pounds of gold with an estimated worth of 12 billion dollars today. In doing so such practices as hydraulic mining operations, practiced into the 1950s, wreaked serious havoc. Silted rivers and ruined farmlands from mining operations provoked legal controversies for years on end. Today, as a result, millions of cubic yards of sediment remain in the Central Valley’s streams and reservoirs, as well as in the clogged channels of the San Francisco–Delta water system. Mercury mined for gold recovery operations has since produced acidic drain waters loaded with heavy-metal deposits. These toxic pollutants include zinc, copper, lead, and cadmium.

Although California’s first bonanza was seemingly over, the gold rush had forever altered its future.

Selected Readings

- On mining in general, see Rodman Paul, California Gold (1947); Andrew Isenberg, Mining California: An Ecological History (2005); John Caughey, ed., Gold Is the Cornerstone (1948); Erwin Gudde, Bigler’s Chronicle of the West: The Conquest of California, Discovery of Gold, and Mormon Settlement (1962); Kenneth N. Owens, ed., John Sutter and the Wider West (1994) and Owens, ed., Riches For All (2002); Alonzo Delano, Life On the Plains and Among the Diggings (1854); William Lewis Manly, Death Valley in ’49 (1924); Elza Edwards, The Valley Whose Name is Death (1940); and Roy and Jean Johnson, eds., Escape From Death Valley (1987).

- Recent scholarship includes books by Malcolm Rohrbaugh, Days of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the American Nation (1999); Mark Eifler, Gold Rush Capitalists (2002); Brian Roberts, American Alchemy: The California Gold Rush and Middle Class Culture (2000); Mary Hill, Gold: The California Story (1999); H. W. Brands, The Age of Gold (2002); J. S. Holliday, Rush For Riches: Gold Fever and the Making of California (1999); Leonard L. Richards, The California Gold Rush and the Coming of the Civil War (2008); and Edwin G. Gudde, California Gold Camps: A Geographical and Historical Dictionary of Camps, Towns, and Localities Where Gold was Found and Mined (2009).

- Ocean routes to the gold fields are described in James P. Delgado, To California by Sea: A Maritime History of the California Gold Rush (1990); Raymond Rydell, Cape Horn to the Pacific (1952); John H. Kemble, The Panama Route (1943); and Oscar Lewis, Sea Routes to the Gold Fields (1949). An original diary is Lucy Kendall Herrick, Voyage to California Written at Sea (1998).

- Regarding overland trail conditions and legality in the diggings see John P. Reid, Policing the Elephant (1996); Charles H. Shinn, Mining Camps: A Study of American Frontier Government (1885); Bayard Taylor, Eldorado, or Adventures in the Path of Empire (2 vols. repr. 1949); Edwin Beilharz and Carlos Lopez, eds., We Were ’49ers: Chilean Accounts of the California Gold Rush (1976); and Jo Ann Levy, They Saw the Elephant: Women and the California Gold Rush (1990).

- Under the pseudonym “Dame Shirley,” Louise Amelia Knapp Smith Clappe wrote The Shirley Letters from the California Mines, edited by Carl I. Wheat (1949). Other accounts include E. Gould Buffum, Six Months in the Gold Mines (1850); Franklin A. Buck, Yankee Trader in the Gold Rush (1930); David M. Potter, ed., Trail to California: The Overland Journal of Vincent Geiger and Wakeman Bryarly (1945); and Irene D. Paden, In the Wake of the Prairie Schooner (1943).

- Mormons in the gold fields is the subject of Kenneth Owens, Gold Rush Saints (2004).

- See also Ralph P. Bieber, Southern Trails to California in 1848 (1937) and his “California Gold Mania,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 35 (June 1948), 3–28; F. P. Wierzbicki, California … A Guide to the Gold Region (1933); George W. Groh, Gold Fever (1966); and James S. Holliday, The World Rushed In (1982). Finally, Gary Kurutz, The California Gold Rush: A Descriptive Bibliography (1997) summarizes scholarship in this field.