31

The Depression Years

Americans had never seen an economic collapse of the magnitude that followed the stock market crash of October 1929. With the labor scene in tatters, jobs grew increasingly scarce. Unions could now hardly demand the closed shop, or even bargain for better working conditions. The Republican administration of President Herbert Hoover seemed powerless to stop the country’s downward financial spiral.

Californians, therefore, sought more direct political solutions to their economic distress. Across the state, swarms of destitute migrants roamed the city streets and dusty farm roads in search of jobs. In the presidential elections of 1932, the Democratic Party nominated a new type of candidate. This was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the highly popular governor of New York. His campaign took “F.D.R.” to the major cities of the Far West, which responded to his magnetic appeal.

The unemployed, many of whom were in despair, had tired of hearing that stock market speculation was the primary cause of the Great Depression. They wanted immediate solutions, especially concerning the weakened local economy. At the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco on September 23, 1932, Roosevelt described in somber terms the concentration of private enterprise in the United States into large business concerns: “Put plainly, we are steering a steady course toward oligarchy, if we are not there already,” he said. He went on to speak of every man’s right to life and to a comfortable living, declaring that “Our government, formal and informal, political and economic, owes to everyone a portion of that plenty sufficient for his needs, through his own work.” When election day came, California voted overwhelmingly for Roosevelt.

But even while FDR campaigned, the state’s economy continued to worsen. Overproduction of both agricultural and commercial commodities hastened the spread of unemployment. Once prosperous industries, farms, and real estate developments were mired down by the national depression. Within a few months, banks – following runs on their holdings by nearly hysterical depositors – were threatened with collapse. To give the state legislature time to devise protective legislation, Governor James “Sunny Jim” Rolph, Jr., ordered a three-day “bank holiday” on March 2, 1933. Two days later, during President Roosevelt’s inauguration, the governor of almost every state had imposed severe restrictions on the withdrawal of private bank funds. On the same day, Rolph extended the California bank holiday.

The country neared economic paralysis, the scarcity of money had reduced some businesses to using a barter system. Everyone hoped that Roosevelt’s “New Deal” would spur recovery. The administration asked Congress to pass sweeping new legislation that virtually put government in partnership with business. Roosevelt proposed that thousands of unemployed workers be hired by civic work projects. Because the energetic new president demonstrated that he viewed the crisis as far from insoluble, Californians looked to him for crucial leadership.

California’s relief activities, now carried on through a State Relief Administration, were, initially, far from adequate to meet emergency conditions. Even at this time, thousands of new migrants descended upon the state, though they were warned not to come in search of jobs. Rumors of high wages “out West” nonetheless convinced many to make a cross-country trip they were to regret. Among the newcomers were 350,000 farmers from the parched Dust Bowl areas of the Middle West, disdainfully called “Okies” or “Arkies” by older stock Californians. The overland trek of the Okies in their rickety “flivvers,” old jalopies heaped with mattresses and children, with blankets, brooms, and pails tied into the mess, and clanking all the while, has been vividly described in John Steinbeck’s poignant novel The Grapes of Wrath.

Most of these migrants arrived in California during 1935 and in the four years thereafter. Because the labor situation was so gravely depressed, even responsible citizens supported legislation to close the state’s borders to indigents. (Later, in 1941, the U.S. Supreme Court declared such laws unconstitutional.) Farm owners became accustomed to paying starvation wages that desperate migrants were forced to accept. Faced with bankruptcy, employers claimed they could not possibly spend money they did not have to improve the working conditions of California’s new refugees.

Both the AFL and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), two rival labor groups, battled in the orchards of Marysville. In the packing sheds of Bakersfield and in the canneries of Fresno both unions sought to organize migrant workers. Moving to combat these efforts, after a wave of field strikes, in 1934 a group of farm owners formed the Associated Farmers of California. This anti-union group came to number 40,000 members, providing more than a match for the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAA), part of the CIO.

Figure 31.1 Migrant mother and baby wait for help with a broken-down truck that contains all of the family’s worldly possessions. Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington (LC-USF34-T01-016453-E).

Governor Rolph had little idea of how to cope with the state’s massive unemployment, especially among migrant workers. He opposed reform of California’s tax structure and signed legislation that caused taxes to fall unfairly upon persons of the lowest income. A sales tax on retail items, including food, was blamed on Rolph. He also vetoed a progressive income tax bill and made the mistake of endorsing a brutal jailbreak lynching. When he died in 1934, “Sunny Jim” was succeeded by his dour lieutenant governor, Frank Merriam, who was more conservative in his rhetoric than in his actions.

Folksinger Woody Guthrie mocked Governor Merriam in one of his ballads about official indolence over just what to do about the Okies and Arkies. Public prejudice against these migrants was born of a combination of insecurity, shame, and racism: in short, it upset Caucasians to see their fellow whites working in the fields in deplorable conditions alongside persons of color. Guthrie’s folksongs, like Steinbeck’s novels, captured the spirit of the Great Depression. Born in Oklahoma, Guthrie had spent several years in Los Angeles, where he sang a ditty on a radio station that he dedicated to “the little man” and “drifting families,” voicing both strength and bitterness in his “talking blues,” a work that expressed his conviction that California was being misused by selfish, scared people. Guthrie, who composed over a thousand songs, is best remembered by his “folk national anthem,” This Land Is Your Land.

In addition to the influx of Arkies and Okies, a growing number of Mexicans slipped over the border in search of jobs, which were extremely hard to come by. Serious problems of education, housing, and assimilation subsequently developed around California’s Mexican minority. Forced to accept the most unpleasant jobs at low wages or to remain unemployed, they clung to their Spanish language, clustered in their own organizations, and retained a largely separate culture. At Los Angeles, Mexican newcomers formed the largest Mexican community in the world outside Mexico. One Mexican immigrant, Ignazio Lozano, founded La Opinión, which became the nation’s largest Spanish-language newspaper.

Members of another minority group, the Filipinos, also competed for jobs as houseboys, laundry workers, dish washers, and fry cooks. Racist sentiment against Filipino farm laborers led to the Watsonville riot of 1930 and to another disturbance at Salinas in 1934, in which many Filipinos were manhandled. Repeating past patterns, by the mid-1930s proposals for the exclusion of Filipinos were voiced in the California legislature. The state eventually offered these immigrants free transportation back to the Philippines if they promised not to return to California.

Meanwhile, thousands of older folk, many of them no longer able to work, became dependent on curtailed incomes. They had believed that life in sunny California would rejuvenate them. During the Great Depression, elderly persons listened with great interest to schemes that promised to alleviate their hardships by redistributing America’s uneven wealth. Among such plans in circulation at the time was a movement known as “Technocracy.” Its chief advocate was Howard Scott, an engineer who wanted to create a utopian society by eliminating poverty. Equipped with elaborate blueprints, he explained his proposed new civilization in abandoned drug stores, garages, and unrented buildings. His ideas did not survive the period. Like Technocracy, other utopian plans hatched during the depression years were identified with a particular personality.

One of these characters was Upton Sinclair, a crusading journalist. Although eccentric, he was actually a highly disciplined writer of 90 books including his searing exposé of the American meat packing industry entitled The Jungle. In 1920, he unsuccessfully sought a congressional seat. After losing the election, he hosted séances in his home, even attracting Albert Einstein and Charlie Chaplin. He next ran unsuccessfully for the Senate. In 1926, and again in 1930, he ran as the Socialist party candidate for governor. Sinclair’s last attempt at public office was in 1934, when he sought the Democratic nomination for governor.

Sinclair’s experimental the EPIC (“End Poverty in California”) plan was tailor-made for the downhearted. He advocated a monthly pension of $50 for widows, the aged, and the handicapped. Earlier, Henry George had championed a heavy tax on idle land. Sinclair too believed that homeowners should be exempt from taxation. His “production for use” scheme called for the state to buy up idle land and factories. This was to help the unemployed. Sinclair also wanted the legislature to issue a new substitute for money called “scrip currency.” President Roosevelt considered Sinclair’s extremist ideas impractical. In 1934, during a bitter gubernatorial election, the press, radio, and film industry (then in conservative control) united against Sinclair. His incumbent opponent, Governor Frank Merriam, portrayed him as a fool and defeated him soundly.

Sinclair, however, was followed by even more radical messiahs. His was an age in which pundits of every description attracted huge audiences of discontented citizens. Among these was Dr. Francis E. Townsend, a retired physician who sold real estate at Long Beach. His campaign slogan was “Youth for work and age for leisure.” In 1934, he proposed his Townsend Old Age Pension Plan. This scheme sought to provide a monthly pension of $200 for every person over the age of 60. Recipients, however, would have to retire from work completely and spend each of these payments within the month it was received. A 2 percent federal tax upon all business transactions was to help finance the plan.

Townsend waged his “crusade” via his newspaper, The Townsend Weekly, and 5,000 clubs organized in his name. By 1937, national Townsend Club membership was estimated at from 3 million to 10 million persons. While even Upton Sinclair considered Dr. Townsend’s plan economic madness, only slowly did Townsend’s followers give up on his ideas.

In 1938, yet another visionary plan, the “Thirty Dollars Every Thursday,” or “Ham and Eggs” proposal, emerged. Its proponents wanted to award a pension to every unemployed person over the age of 50. Payment of pensions and state taxes would be made in scrip or warrants financed by a compulsory stamp purchase system. In the state elections of 1938 and 1939, the measure actually came close to adoption, despite the fact that critics labeled it economically irresponsible.

This movement, like Sinclair’s EPIC plan and Townsend’s pension scheme, can best be understood in terms of the despair and confused thinking of the depression years. Yet President Roosevelt’s unwillingness to include such locally improvised plans in his sweeping recovery-minded legislation doubtless contributed to their demise. Passage of the more realistic federal Social Security Act of 1935 was, however, influenced by and partly in response to California’s experimental public welfare schemes.

A series of congressional measures, most of which survived Supreme Court tests of their constitutionality, enabled Roosevelt to deliver on his campaign promises of a “New Deal” featuring relief, recovery, and reform. Dozens of new federal agencies, with abbreviated alphabetic titles, were established to perform functions designed to bring back prosperity. Some of these organizations worked in partnership with state relief agencies.

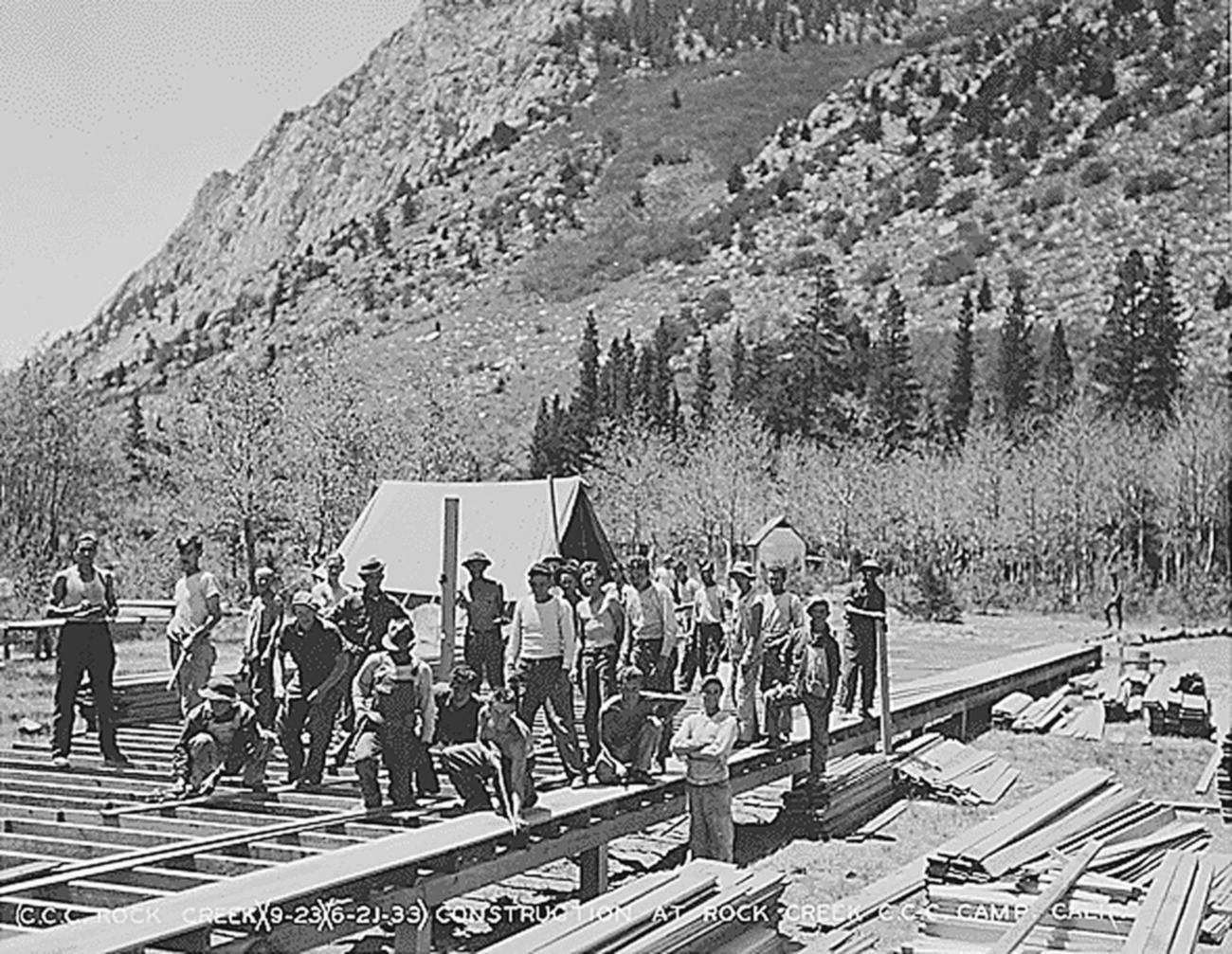

With funding to construct Hoover Dam and the Central Valley Project, the federal government helped to finance other power, water-reclamation, flood-control, and navigation projects. These would affect markedly the future of California. By the mid-1930s, the short-term relief benefits of massive government aid had become evident. Like their counterparts throughout the nation, destitute Californians depended upon weekly government checks to sustain them until they could find permanent employment. In addition to this direct relief, unemployed young men were given “make-work” jobs in the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Under the supervision of the CCC staff, young men in California constructed mountain trails and firebreaks on federal forest lands and in the six new state parks established in California during 1933. The CCC mailed the bulk of the workers’ salaries home to their needy parents. Other young people in college were aided by funds dispensed by the National Youth Administration (NYA). Many of their fathers, meanwhile, worked on Works Progress Administration (WPA) or Public Work Administration (PWA) construction projects or as federally employed writers and artists.

Figure 31.2 Civilian Conservation Corps workers in California at Camp Rock Creek, 1933. National Archives, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library Public Domain Photographs, 1882–1962 (NLR-PHOCO-A-48223762 (27)).

Though resisted by conservatives, these New Deal initiatives helped to alleviate economic hardship. Their costs, moreover, seemed modest later when compared to federal expenditures made during and after World War II. No state benefited more from the federal relief programs than did California. There, the CCC built hundreds of new schools, parks, roads, and beach facilities during the Great Depression. In addition to the larger-scale projects previously mentioned, these new undertakings contributed materially to the development of the state.

Although the Democratic Franklin Roosevelt won California in four successive national elections, Californians had not seated a Democratic governor since 1894. In 1938, Culbert Olson, an advocate of President Roosevelt’s reforms, broke the string of Republicans when he assumed the governorship near the end of the New Deal, just as public pressure for reform had abated. In supporting migrant laborers and confronting agricultural malaise, Olson butted heads with the Associated Farmers, the large growers fiercely opposing all forms of governmental intervention.

Nonetheless, following an upswing of business activity after 1937, labor became more popular. The CIO began to attract more unorganized laborers. That union renewed its interest in unskilled laborers, once represented by the IWW. For years, the Coast Seamen’s Union had also agitated for better working conditions. Its Norwegian leader, Andrew Furuseth, a pioneer crusader for seamen’s rights, had fought for the extermination of such evils as “the crimp.” Sailors were then still forced to pay a fee to a “crimp,” or labor broker, in order to join ship crews. Waterfront boardinghouses, providing seamen with beds, meals, and clothing, also charged exorbitant fees. Their operators regularly turned over to shipmasters those unemployed seamen who were deeply in their debt. Furuseth’s struggle to obtain seamen’s rights eventually was carried on to the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific.

To obtain employment, waterfront workers joined the Longshoremen’s Association, actually an open-shop company union through which shippers controlled hiring and wages. Worker discontent paved the way for the entrance of radicalism into the maritime labor movement, which now acquired new organizers. Among these was Harry Bridges, a spellbinding Australian-born longshoreman.

Maritime employers labeled the militant Bridges a dangerous alien radical, if not a Communist. But thousands of longshoremen up and down the Pacific Coast stood behind his leadership. By 1934, he staged a massive strike that affected all shipping from San Diego to Seattle. Bridges sought a minimum 30-hour week for his dock workers at wages of $1 an hour. He also objected to the hiring of longshoremen by company foremen who selected their favorite workers.

During the great maritime strike of 1934, Bridges tied up ship traffic at San Francisco for 90 days. In sympathy with longshoremen, other transport workers went out on strike too. As hundreds of ships lay idle, entire cargoes rotted and rusted on piers and in warehouses. On July 5, known as “Bloody Thursday,” a violent episode erupted. After the San Francisco police moved against picket lines with tear gas, two union pickets were shot to death and more than 100 men, including police, were wounded. Almost 150,000 workers then walked off the job, paralyzing the San Francisco Bay area. When the governor called out the National Guard, the move only intensified the resentment of strikers.

The 1934 “general strike” actually damaged the long-term interests of unionism. Eventually the longshoremen agreed to submit their demands to arbitration. Although they won some concessions from management, settlement of this strike by no means brought peace to the San Francisco waterfront. Other labor stoppages, though less intensive, occurred throughout the 1930s. These strikes only fueled the continuing public criticism of unions.

A jurisdictional altercation between Bridges and other labor leaders ultimately led Bridges to take his longshoremen into the CIO. Because of his power, from 1936 onward the Hearst press made demands for his deportation. Eventually, the House Un-American Activities Committee charged that various CIO unions were under Communist leadership and control. The courts upheld the legality of Bridges’s radical unionization techniques, however, and he retained considerable power.

Demands for unionization also spread to Los Angeles, center of the open shop or “American Plan.” By 1935, the port of San Pedro had been unionized. Similar pressures filtered back from the city’s waterfront into Los Angeles proper. Its plasterers, hod carriers, plumbers, typographers, tire workers, steamfitters, and auto assemblers also made new demands upon management.

By the end of the 1930s, a revived era of negotiation had begun in the relations between California labor and management. Harry Bridges eventually came to call strikes an “obsolete weapon,” while Roger Lapham, chairman of the board of the American-Hawaiian Steamship Company (and later mayor of San Francisco), agreed to participate in collective bargaining through the federal National Labor Relations Board.

Against the grave social dislocations of the depression years, the figure of William Randolph Hearst stands out in bold relief. Born into a wealthy family at San Francisco in 1863, his father, Senator George Hearst, had created a mining fortune. Young Will attended Harvard University and in 1887, at the age of 24, was virtually handed the San Francisco Examiner. Through his willingness to invest vast amounts of his father’s money, Hearst made the Examiner the most powerful paper on the West Coast. His reputation as a young and energetic publisher was first earned by the scathing attacks he made on the Southern Pacific Railroad. At first, Hearst was a reformist crusader, but by the 1930s he bore little resemblance to the liberal of earlier decades. Like many disgruntled businessmen, Hearst came to believe that reform had gone far enough and that conservatism must reverse the power of labor unions, of government, and, in particular, of flighty New Dealers.

Throughout his 88 years, Hearst remained an enigma, even to close associates. Though outwardly shy, he made his power felt even at the international level through his chain of some 30 newspapers, 13 magazines, and several radio stations. Hearst came to be associated with a remarkable number of issues and events. Prominent among these were the Spanish-American War, which he helped cause. Hearst hated the two Roosevelts and distrusted all minorities. He was an opponent of United States entry into both World Wars and of internationalism. Most thinking persons were offended by his prejudices, and nearly always repelled by his personal tastes.

At the heart of Hearst’s empire lay his newspaper chain. He bought up papers all over the country and made them successful. Their sensational reporting, as well as slanted editorials, appealed to a less-than-educated readership. His so-called yellow journalism became the despair of Hearst’s critics. During California’s depression decades, the “Chief” grew ever more eccentric, to the point that even his fellow conservatives shunned him. The Hearst press spewed hate at reformist Governor Olson and fulminated against attempts to “tinker” with the currency, “coddle” the unemployed, and “socialize” the country.

Figure 31.3 Aerial view of San Simeon, William Randolph Hearst’s castle.

Courtesy Hearst Castle ® / California State Parks.

The headquarters of Hearst’s domain was his San Simeon estate, on the rocky coast north of San Luis Obispo. In the interwar years, he poured $35 million into the construction of an immense castle there. Stocking it with art treasures he had acquired from all over the world, Hearst made San Simeon a rendezvous for guests drawn from the movie industry as well as the world of art, music, literature, and public affairs. Hearst, like his mother, Phoebe Apperson Hearst, also subsidized philanthropic and educational institutions.

By 1935, Hearst’s personal empire was valued at $200 million. His holdings included: seven castles; warehouses full of antique furniture, paintings, and tapestries; ranches on which he raised 10,000 beef cattle; several zoos; hunting lodges; and beach homes.

Movie director Orson Welles’s 1940 film Citizen Kane drew a stark picture of Hearst’s life through its thinly veiled principal character, newspaper mogul Charles Kane. As times changed, the living anachronism that was “Citizen Hearst,” as one of his biographers dubbed him, became ever more apparent. After World War II, the Hearst dynasty gradually crumbled. By the mid-1960s, his two major papers, the San Francisco Examiner and the Los Angeles Examiner, gave way to the Chronicle and the Times. Now the Examiners, both morning papers, had to be merged with the Hearst evening newspapers to meet the competition of suburban dailies as well as radio and television newscasts. Falling circulation led his heirs to enter other fields of endeavor.

The life of William Randolph Hearst continues to generate new biographies of the autocrat. He personified like no other public figure the enormous gap between wealthy and working-class Californians during the cruel depression that had enveloped their state.

Selected Readings

- Regarding this period see Leonard Leader, Los Angeles and the Great Depression (1991). See also William Mullens, The Depression and the Urban West Coast, 1929–1933 (1991). On migration into the state, see James Gregory, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and the Okie Culture in California (1989); Charles J. Shindo, Dust Bowl Migrants in the American Imagination (1997); Walter J. Stein, California and the Dust Bowl Migration (1973); and Dorothea Lange and Paul S. Taylor, An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion (1939).

- Other depression-era sources include Luther Whiteman and Samuel L. Lewis, Glory Roads: The Psychological State of California (1936); Jackson K. Putnam, Old Age Politics in California (1970); Abraham Holtzman, The Townsend Movement: A Political Study (1963); Gilman Ostrander, The Prohibition Movement in California (1957); and Abe Hoffman, “A Look at Llano: Experiment in Economic Socialism,” California Historical Society Quarterly 40 (September 1961), 215–236.

- Regarding Upton Sinclair, see his I, Candidate for Governor – and How I Got Licked (1935). The latest biography is Anthony Arthur, Radical Innocent (2006). See also Greg Mitchell, The Campaign of the Century: Upton Sinclair’s Race for Governor of California and the Birth of Media Politics (1992); Fay Blake and H. M. Newman, “Upton Sinclair’s Epic Campaign,” California Historical Quarterly 63 (Fall 1984), 305–319; Judson Grenier, “Upton Sinclair: A Remembrance,” California Historical Society Quarterly 47 (June 1969), 165–169, and Grenier, “Upton Sinclair: The Road to California,” Southern California Quarterly 56 (Winter 1974), 325–336.

- On reform and labor, consult Tom Sitton, “Another Generation of Urban Reformers: Los Angeles in the 1930s,” Western Historical Quarterly 18 (July 1987), 315–332; Woodrow C. Whitten, Criminal Syndicalism and Law in California (1969); Philip Taft, Labor Politics American Style: The California State Federation of Labor (1968); Robert W. Cherny, “The Making of a Labor Radical: Harry Bridges, 1901–34,” Pacific Historical Review 64 (August 1995), 363–388; Hyman Weintraub, Andrew Furuseth: Emancipator of the Seamen (1959); Robert Knight, Industrial Relations in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1900–1918 (1960); Paul S. Taylor, The Sailors’ Union of the Pacific (1923); Alexander Saxton, “San Francisco Labor and the Populist and Progressive Insurgencies,” Pacific Historical Review 34 (November 1965), 421–438; Ira Cross, History of the Labor Movement in California (1935); Mike Quin, The Big Strike (1949); Paul Eliel, The Waterfront and General Strikes San Francisco, 1934 (1934); and Harvey Schwartz, Solidarity Stories: An Oral History of the ILWU (2009).

- About California’s governors, see H. Brett Melendy and Benjamin F. Gilbert’s The Governors of California (1965). See also Robert E. Burke, Olson’s New Deal for California (1952).

- Hearst’s biographers include Ben Procter, William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years (1998); Oliver Carlson and Ernest S. Bates, Hearst: Lord of San Simeon (1937); John Tebbel, The Life and Good Times of William Randolph Hearst (1952); John K. Winkler, William Randolph Hearst: A New Appraisal (1955); and W. A. Swanberg, Citizen Hearst: A Biography of William Randolph Hearst (1961).

- Regarding competition between farm workers, see Gilbert Gonzalez, Labor and Community: Mexican Citrus Worker Villages … (1994); Camille Guerin-Gonzales, Mexican Workers and American Dreams (1994); Wayne Cornelius, Leo Chavez, and Jorge Castro, Mexican Immigrants and Southern California (1982); Richard Griswold del Castillo, The Los Angeles Barrio, 1850–1890 (1980); Vicki Ruiz, Cannery Women, Cannery Lives (1987); Devra Weber, Dark Sweat, White Gold: California Farm Workers (1994); Cletus E. Daniel, Bitter Harvest: A History of California Farm Workers, 1870–1941 (1981); and Harold A. De Witt, “The Watsonville Anti-Filipino Riot of 1930,” Southern California Quarterly 61 (Fall 1979), 291–302. Regarding the field and citrus worker strikes of the 1930s see Gilbert G. Gonzalez, Mexican Consuls and Labor Organizing (1999) and Matt Garcia, A World of Its Own: Race, Labor, and Citrus in the Making of Greater Los Angeles, 1900–1970 (2001).