CHAPTER FIVE

THE LIBRARY, A–Z

For a great many years until my retirement I biked back and forth to Stanford every day from my home, stopping many days to admire the Rodin statues of the Burghers of Calais, or the gleaming mosaics on the chapel dominating the Quad, or to browse at the campus bookstore. Even after retirement I continued to bike around Palo Alto, running errands or visiting friends. But lately I’ve lost confidence in my balance, and so I avoid biking in traffic and limit my riding to bike paths for thirty or forty minutes at sundown. Though my routes have changed, the experience of biking has always been one of liberation and contemplation, and lately when I ride, the experience of the smooth, swift motion and the breeze in my face invariably transports me into the past.

Aside from an intense ten-year affair with a motorcycle during my late twenties and early thirties, I’ve been faithful to bicycling since I was twelve, when, after a long, hard campaign of begging and wheedling, my parents gave in and bought me a flashy red American Flyer for my birthday. I was a persistent beggar and discovered at an early age a supremely effective technique, a technique that never failed: simply make a linkage between my desired object and my education. My parents were not forthcoming with money for any type of frivolity, but when it came to anything even remotely related to education—pens, paper, slide rules (remember those?), and books, especially books—they gave with both hands. Hence, when I told them I would use the bicycle to visit the grand Washington Central Library at Seventh and K Streets more often, they could not refuse my request.

I kept my side of the bargain: every Saturday, without fail, I filled my bicycle leatherette saddlebags with the six books (the library limit) I had digested since the previous Saturday and took off on the forty-minute ride for new ones.

The library became my second home and I spent hours there each Saturday. My long afternoons served a dual purpose: the library put me in contact with the larger world I longed for, a world of history and culture and ideas, and at the same time it eased my parents’ anxiety and gave them the satisfaction of knowing that they had begotten a scholar. Also, from their standpoint, the more time I spent indoors reading, the better: our neighborhood was a dangerous one. My father’s store and our second-floor apartment were located in a low-income neighborhood of segregated Washington, DC, a few blocks from the border of the white neighborhood. The streets were rife with violence, theft, racial skirmishes, and drunkenness (much of that fueled by liquor from my father’s store). During the summer school vacations, they were wise to keep me off the dangerous streets (and out of their hair) by sending me, at considerable expense, from the age of seven onward, to summer camps in Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, or New Hampshire.

The enormous reception hall on the library main floor inspired such awe that I tiptoed as I moved through it. In the very center of the first floor stood a massive bookcase housing biographies, in alphabetical order by subject. Only after I had circled it a great many times did I work up the nerve to approach the officious librarian for guidance. Without a word, she shushed me with a forefinger over her lips and pointed to the great marble circular stairway leading to the children’s section on the second floor where I belonged. Crestfallen, I followed her instructions, but nevertheless, each time I came to the library I continued to case the biography bookcase, and at some point I developed a plan: I would read one biography a week, beginning with a person whose name started with “A,” and work my way through the alphabet. I started with Henry Armstrong, a lightweight boxing champion of the 1930s. From the B’s I remember Juan Belmonte, the gifted matador of the early nineteenth century, and Francis Bacon, the Renaissance scholar. There was C for Ty Cobb, E for Thomas Edison, G for Lou Gehrig and Hetty Green (“The Witch of Wall Street”), and so on. In the J’s I discovered Edward Jenner, who became my hero for having eliminated smallpox. In the K’s I met Genghis Khan, and for weeks I wondered whether Jenner had saved more lives than Genghis Khan had destroyed. The K’s also housed Paul de Kruif’s Microbe Hunters, which inspired me to read many books about the microscopic world; the following year, I worked on weekends as a soda jerk at Peoples Drug Store and saved enough money to buy a polished brass microscope, which I own to this day. The N’s offered me Red Nichols, the trumpet player, and introduced me also to a weird dude named Friedrich Nietzsche. The P’s led me to Saint Paul and Sam Patch, the first to survive a plunge over Niagara Falls.

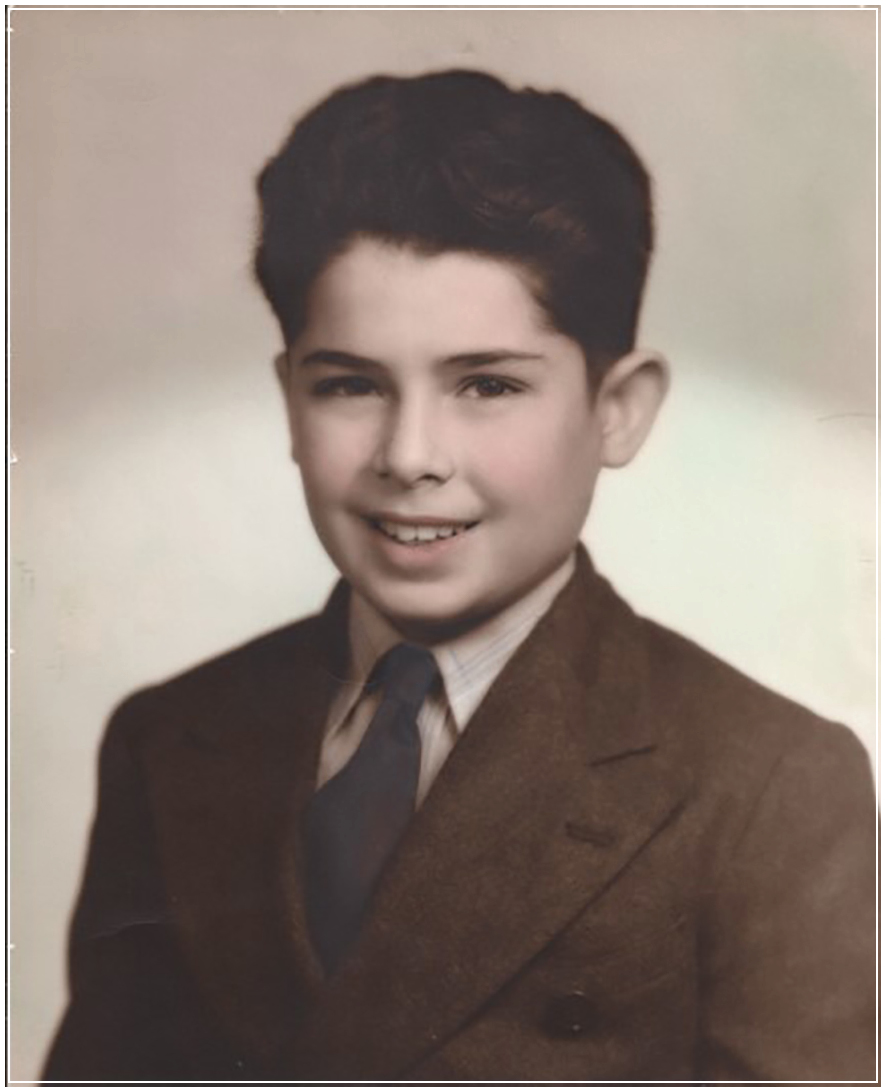

I recall ending my biography project at the T’s, where I discovered Albert Payson Terhune. I got sidetracked in the weeks that followed devouring his many books about such extraordinary collies as Lad and Lassie. Today I know I suffered no harm from this haphazard reading pattern, no harm from being the only child of ten or eleven in the world who knew so much about Hetty Green or Sam Patch, but still, what a waste! I yearned for some adult, some mainstream American mentor, someone like the man in the seersucker suit who would enter my father’s grocery store and announce that I was a lad of great promise. Looking back now, I feel tenderness for that lonely, frightened, determined young boy, and awe that he somehow made his way through his self-education, albeit haphazardly, without encouragement, models, or guidance.