CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

COMING ASHORE

In 1964, three years into my career at Stanford, I decided to attend an eight-day National Training Laboratory Institute at Lake Arrowhead in Southern California. The weeklong institute program offered many social psychological activities, but the heart of it, and my reason for going, was the daily three-hour small-group meeting. I arrived a few minutes early the morning of the first meeting, took one of the thirteen chairs placed in a circle, and glanced about at the leader and the other early arrivals. Though I had much experience leading therapy groups, and was heavily involved in group therapy research and teaching, I had never been a member of a group. It was time to remedy that.

No one spoke as the others filed in and took seats. At 8:30, the leader, Dorothy Garwood, a therapist in private practice with two PhDs (biochemistry and psychology), stood up and introduced herself: “Welcome to the 1964 Lake Arrowhead NTL Institute,” she said. “This group will be meeting every morning at this time for three hours for the next eight days, and I’d like us to keep everything we say, all of our comments, in the here-and-now.”

A long silence followed. I thought, “That’s all?” and looked around to see eleven faces radiating perplexity and eleven heads shaking in bewilderment. After a minute, members responded:

“That’s a pretty skimpy orientation.”

“Is this some kind of joke?”

“We don’t even know anyone’s name.”

No response from the leader. Gradually, the collective uncertainty began to generate its own energy:

“This is pathetic. Is this the kind of leadership we’re getting?”

“That’s rude. She’s doing her job. Don’t you get that this is a process group? We have to examine our own process.”

“Right, I have a hunch, more than a hunch, she knows exactly what she’s doing.”

“That is blind faith: I’ve never liked blind faith. The truth is we’re floundering, and where is she? Sure as hell not helping us.”

There were a few pauses between comments as members waited for the leader to respond. But she smiled and remained silent.

Other members pitched in.

“And, anyway, how are we supposed to stay in the here-and-now when we have no history together? We’ve just met today for the first time.”

“I’m always uncomfortable with this kind of silence.”

“Yeah, me too. We’re paying a good bit of money and we’re sitting here doing nothing and wasting time.”

“Personally, I like the silence. Sitting here quietly with all of you mellows me out.”

“Me, too. I just slip into meditation. I feel focused, ready for anything.”

As I engaged in this interchange and reflected upon it, I had an epiphany—I learned something that I later incorporated into the very core of my approach to group therapy. I had just witnessed a simple but extraordinarily important phenomenon: all the group members being exposed to a single stimulus (in this instance, a leader asking that all comments remain in the here-and-now), and the members responding in very different ways. A single shared stimulus and eleven different responses! Why? There was only one possible solution to this puzzle: There are eleven different inner worlds! And these eleven different responses may be the royal road into these different worlds.

Without the leader’s assistance, we each then introduced ourselves and said something about what we did professionally and why we were there. I noted that I was the only psychiatrist—there was one psychologist, and the rest were educators or social scientists.

I turned and addressed the leader directly. “I’m curious about your silence. Could you say a bit about your role here?”

This time she answered (briefly): “My role is to be the leader and to hold all the feelings and fantasies that members have about leaders.”

We continued meeting for the next seven days and began examining our relationships with one another. The psychologist member of the group was a particularly angry individual and often laced into me for being pompous and overbearing. A few days in, he related a dream he had had about being chased by a giant—which seemed to be me. And ultimately, he and I did a good bit of work—I on my discomfort with his anger and he on the competitive feelings I aroused in him—and we worked through some of the distrust between our respective professions.

Since I was the only physician at this conference, I was called upon to care for and eventually hospitalize a member in another group who developed a psychotic reaction to the stress generated in his group. This outcome made me even more aware of the power of the small group—power not only to heal but also to harm.

I grew to know Dorothy Garwood well, and years later she and her husband and Marilyn and I had a lovely vacation on Maui. She was by no means a withholding person, but had been trained in a tradition from the Tavistock Clinic—a large psychotherapy training and treatment center in London—in which the leader remained outside the group and confined all her observations to mass group phenomena. Three years later, on a sabbatical at the Tavistock Clinic, I understood more clearly the rationale for her leadership posture.

When our family of five had first arrived in Palo Alto after my discharge from the army nearly three years before, in 1962, Marilyn and I had set about finding a place to live. We could have purchased a home in the faculty housing area of Stanford, but, as in Hawaii, we chose a more diverse neighborhood. We bought a thirty-year-old house (almost ancient by California standards) fifteen minutes from the campus. Economics were so different then: with a small income, we had no difficulty buying a home on an acre of land for $32,000. The price was three times my annual Stanford income; today, the Palo Alto economy has changed so much that an equivalent home would cost thirty to forty times a young professor’s salary. My parents gave us the $7,000 down payment on the house, and that was the last time I accepted money from them. Still, even after I completed my training and we were a family of six, my father always insisted on picking up the check at restaurants. I liked his taking care of me and offered only flimsy resistance. And I have passed his generosity on by doing exactly the same for my adult children (who, in turn, also put up flimsy resistance). It’s a pathway to being remembered: my father’s face often comes to mind as I pay the bill for my children. (And we have also been able to give our children down payments on their first houses.)

When I first reported to my department, I learned that I was assigned to be the medical director of a large ward at the new Stanford Veterans Administration Hospital, ten minutes from the medical school and entirely operated by Stanford faculty. Though I supervised residents, organized a process group for medical students (i.e., a group in which we studied the way we related to one another), and had free time to attend departmental lectures and research symposia, I was not happy at the VA. I felt that too many of the patients, almost all World War II veterans, were unreceptive to my approach to therapy. Quite possibly the secondary gains were simply too great: free medical care, free housing and food, and a comfortable dwelling place. Toward the end of my first year, I told David Hamburg that I foresaw few research opportunities for my particular interests at the VA. When he inquired where I wished to work, I suggested the outpatient department at Stanford, the hub of the training program for residents and a site where I could organize a group therapy program for training and research. Having observed my work and attended a couple of my grand rounds presentations, he had sufficient confidence in me to agree to my request. He was never anything but helpful and supportive, and from that point on, for a great many years, I had no administrative responsibility and almost total freedom to follow my own clinical, teaching, and research interests.

In 1963, Marilyn completed her doctorate (with a dissertation titled The Motif of the Trial in the Works of Franz Kafka and Albert Camus) in the program of comparative literature at Johns Hopkins. She flew to Baltimore for the oral exams, passed her orals, and received her doctorate with distinction. She came back hoping for a position at Stanford, but was devastated when the head of the French Department, John Lapp, told her: “We don’t hire faculty wives.”

A generation later, as my consciousness of women’s issues increased, I might have sought a position at another university broad-minded enough to evaluate her solely on her merit, but in 1962 that thought never crossed my mind, nor Marilyn’s. I felt for her. I knew she deserved a Stanford position, but we both accepted the situation and simply set about looking for alternatives. Shortly thereafter, the dean of humanities at the brand new California State College at Hayward contacted Marilyn. Having heard about her from a Stanford colleague, he drove to our home and offered her a position as an assistant professor of foreign languages. Teaching at Hayward entailed a commute of almost an hour each way four days a week, which she negotiated for the next thirteen years. Marilyn’s entry salary was $8,000—$3,000 less than my entry salary at Stanford. But our two salaries allowed us to live comfortably in Palo Alto, to pay for a full-time housekeeper, and even to take several memorable trips. Marilyn had a fulfilling career at California State and was soon promoted to tenured associate professor and then to a full professorship.

For the next fifteen years at Stanford I was heavily involved in group therapy, as a clinician, teacher, researcher, and textbook author. I started a therapy group in the outpatient clinic that my students, the twelve first-year psychiatric residents, observed through a two-way mirror—just as I had watched Jerry Frank’s group when I was a student. At first I co-led it with another faculty member, but the following year I began the practice of leading it with a psychiatric resident who stayed one year and then was replaced by another resident.

My approach had been evolving steadily toward a more personal, transparent form of leadership and moving away from an aloof professional style. Since the group members, all informal Californians, referred to each other by first name, I felt more and more awkward referring to them by their last name or calling them by their first names and expecting them to refer to me as “Dr. Yalom,” so I took the shocking step of asking the group to call me “Irv.” For many years, however, I still clung to my professional identity by wearing my white hospital coat like all the other medical professional staff at the Stanford Hospital. Eventually I gave that up as well, coming to believe that what mattered in therapy was personal honesty and transparency, not professional authority. (I never threw out that white coat—it hangs still in the back of a closet at home—a souvenir of my identity as a medical doctor.) But despite doffing the accoutrements of my field, I still hold fast to my respect for medicine and the entire Hippocratic oath, with its many clauses, such as: “I will practice my profession with conscience and dignity” and “The health of my patient will be my first consideration.”

After each group therapy session, I dictated extensive summaries for my own understanding and my teaching. (Stanford generously provided a secretary.) At some point—I don’t recall the precise stimulus—it occurred to me that it might be useful to patients to read my summary of the session and my post-group reflections. This led to a bold, highly unusual experiment in therapist transparency: the day following each meeting, I mailed a copy of the group summary to all the members. Each summary described the major issues of the session (generally two or three themes) and each member’s contributions and behavior. I added the reasons behind each of my statements in the group and often added comments about things I wish I had said or things I regretted having said.

Often the group began a session by critiquing my summary of the previous meeting. Sometimes members disagreed, and sometimes they pointed out omissions, but almost always the meeting began with more energy and interaction than it had before. I found this practice to be so useful that I continued these summaries as long as I led groups. When residents co-led the group with me, they wrote the summary every other week. The summaries require so much time and self-exposure, however, that, to the best of my knowledge, few, if any, group therapists in the country followed suit. Though some therapists were critical of my self-exposure, I cannot recall a single instance in which sharing my thoughts and my personal feelings was not helpful to the patient. Why did such self-exposure come so easily to me? For one thing, I had chosen not to enroll in any postgraduate training—no Freudian or Jungian or Lacanian analytic institutes. I was entirely free of governing rules, and was guided only by my results, which I carefully monitored. A number of issues may have been at play: my ingrained iconoclasm (evident in my early responses to religious belief and ritual), my negative personal experience in analysis with an inexpressive and impersonal analyst, and the experimental atmosphere in my young department, overseen by an open-minded chairman.

Weekly department meetings were not my cup of tea: I always attended but rarely spoke. None of the subject matter—funding, obtaining grants, allocation or bickering over space, relationships with other departments, deans’ reports—interested me. What did interest me was listening to Dave Hamburg speak. I admired his thoughtful reflections, his methods of conflict resolution, and, above all, his amazing rhetorical ability. I love the spoken word in the same way others might love a musical performance, and I am entranced by the words of a truly gifted speaker.

It was obvious that I had no administrative skills, and I never volunteered or was put in charge of anything. Frankly, I just wanted to be left alone to pursue my own research, writing, therapy, and teaching. And almost immediately I began contributing articles to professional journals. This was what I enjoyed and where I felt I had something to offer. I sometimes wonder if I didn’t feign administrative ineptness. It’s possible, too, that I may have felt powerless to compete with the other young Turks in the department, all of whom were jockeying for power and recognition.

I chose to attend that Lake Arrowhead conference not only to have the experience of being a group member but also to learn as much as possible about the “T-group,” an important, nonmedical group phenomenon that emerged in the 1960s and was sweeping the country. (The “T” in T-group stood for “training”—that is, developing skills both in interpersonal relationships and in group dynamics.) The founders of this approach, leaders of the National Education Association, were not clinicians but scholars of group dynamics who wanted to alter attitudes and behavior in organizations and, later, help individuals become more sensitive to others. Their organization, the National Training Laboratories (NTL), held seminars, or social laboratories, of several days’ length in Bethel and Plymouth in Maine, and later, the one I attended in California at Lake Arrowhead.

The NTL laboratory consisted of many activities: the small skills training groups, discussion and problem-solving groups, team-building groups, large groups. But it soon became clear that the small T-groups, in which members gave one another instantaneous feedback, were, by far, the most dynamic and compelling exercise.

Gradually, over the years, as the NTL groups moved west and as Carl Rogers entered the field, the T-group shifted its emphasis to individual personal change. “Personal change!” Sounds a lot like therapy, doesn’t it? Members were encouraged to give and receive feedback, to be participant observers, to be authentic, to take risks. Eventually, the ethos shifted increasingly toward a type of psychotherapy. The groups sought to change attitudes and behavior and to improve interpersonal relationships—and soon one commonly heard slogans such as “Therapy is too good to be offered only to the sick.” The T-group evolved into something new: “group therapy for normals.”

It’s not surprising that this later development greatly threatened psychiatrists, who viewed themselves as owners of psychotherapy and regarded encounter groups as a wild, illicit form of therapy encroaching on their territory. I felt quite differently. For one thing, I was impressed with the research approach of the founders of the field. One of the early pioneers was the social scientist Kurt Lewin, whose dictum “No research without action, no action without research,” generated a vast, sophisticated body of data that I found far more interesting than the medically based group therapy research.

One of the most important things I drew from my Lake Arrowhead group experience was the singular focus on the here-and-now, and I began to implement that forcefully in my own work. As I learned at Lake Arrowhead, it is not enough to tell group members to focus on the here-and-now: we need to supply both a rationale and a roadmap. Over time I developed a short preparation talk that I gave to patients before they entered the group, in which I emphasized that a great many of their interpersonal problems would be re-created in the group, thus offering them a marvelous opportunity to learn more about themselves and to effect change. It followed (and I repeated this more than once) that their task in the group was to understand everything they could about their relationship with every patient in the group and with the group leaders. Many new members would generally find some aspects of the preparation puzzling, and often they would raise the objection that their problem was with their boss, or their spouse, or with friends, or with their anger, and it made no sense to focus on their relationships with group members because they would never see these people in the future.

In response to these common questions, I explained that the group is a social microcosm, and that the issues raised in the therapy group would replicate or resemble the types of interpersonal issues that initially brought them into therapy. This step, I’d learned, was crucial. Later, I conducted and published research demonstrating that patients who were effectively prepared for group therapy fared much better in therapy than those who were not well prepared.

I continued my association with the T-group movement for several years and was part of the faculty of NTL workshops at Lincoln, New Hampshire, as well as in a weeklong workshop for CEOs in Sandusky, Ohio. To this day I am grateful to T-group pioneers for showing me the way to lead and to research interpersonally based groups.

Gradually over the years, I fashioned an intensive group therapy training program for psychiatry residents consisting of several components: a weekly lecture, observation and post-group discussion of my weekly therapy group, having the residents lead a therapy group with weekly supervision, and lastly, participating in a weekly personal process group that I led with a colleague.

How did overworked first-year residents respond to spending this much time learning about group therapy? With a good bit of grousing! Some busy residents particularly resisted the two hours spent each week observing my group and often showed up late or skipped sessions entirely. But as the weeks passed, an unexpected phenomenon occurred: as the group members grew more involved with one another and took more risks, the students grew more and more interested in the drama unfolding before them and the attendance rate sharply increased. Soon they were referring to the group as “Yalom’s Peyton Place” (a takeoff on the name of a TV soap opera in the 1960s). I think of the effect as similar to being engrossed in a well-structured story or novel, and I consider it a propitious sign when therapists are eager to see what will happen next. Even now, after half a century of practice, I generally look forward to each new session, whether individual or group, with anticipation about what new developments will transpire. If that feeling is absent, if I approach a session with little anticipation, I imagine the patient may be experiencing a similar feeling and make an effort to confront and alter that.

What effects did student observation have on the patients? That gigantic question worried me a great deal as I noticed how edgy group members were when students were behind the mirror. I tried reassuring patients that student psychiatrists operated under the same confidentiality rules that professional therapists followed, but that was of little help. Then I tried an experiment: I would attempt to turn the annoying presence of observers into something positive. I asked group members and students to switch places for twenty minutes at the end of the meeting. Thus the group members, in the observation room, observed my post-meeting discussion with the students. This step instantly enlivened both the therapy process and the teaching! The therapy group members listened with keen interest to the students’ observations about them, and the students felt like they were under so much scrutiny that they paid sharper attention to their observation of the group. Eventually I added yet another step: the group members had so many feelings about the observers’ commentary and about the observers themselves (whom they often adjudged to be more uptight than group members) that they wanted additional time to discuss their observations of the observers. So I tacked on an additional twenty minutes in which the students went back to the observation room, and the patients and I returned to the group room and discussed the observers’ comments. I realize this is far too time-consuming for everyday practice, but I believe that the format substantially increased the effectiveness of both the therapy group and the teaching.

All this was very new. This was a time when I was grateful not to be a member of some traditional school of therapy. I gave myself free rein to create new approaches and had learned enough about outcome research to test my assumptions. Looking back, I surprise myself. Many veteran therapists would feel queasy about others observing their therapy, and yet I felt perfectly comfortable with observation. This confidence doesn’t match with my inner vision of myself—somewhere in there is the anxious, ill-at-ease, self-doubting adolescent and young man that I was. But in the matter of psychotherapy, and especially group therapy, I had come to feel entirely comfortable taking risks and acknowledging mistakes. I had some anxiety about these innovations, but anxiety was old stuff for me and I had learned to tolerate it.

For my eightieth birthday I had a reunion party at my home and invited all my residents from those early years at Stanford. Many of them brought up their group therapy training experience and commented that, in their entire course of training, watching my group was the only time they ever observed firsthand a senior clinician doing therapy. Of course, this brought to mind my own training at Hopkins and that tiny-mirrored window through which we watched a therapy group. So, thank you, Jerry Frank.

University faculty members are not promoted for teaching. That old chestnut, publish or perish, is no jest: it is a fact of life in academia. The twenty groups in the outpatient program provided an excellent opportunity for research and publication. I examined how therapists can best prepare patients for group therapy, how to compose groups, why some members dropped out of the groups early, and what the most effective therapeutic factors were.

As I continued to teach group therapy, I realized that a comprehensive textbook was sorely needed, and all my experiences—lectures, research, and therapy innovations—could be incorporated in a textbook. A few years into my work at Stanford, I began outlining such a book.

During this period, I also had a strong connection to the Mental Research Institute (MRI), a collective of innovative clinicians and researchers, such as Gregory Bateson, Don Jackson, Paul Watzlawick, Jay Haley, and Virginia Satir. For an entire year, I spent every Friday in an all-day conjoint family therapy course taught by Virginia Satir, and I grew to respect the effectiveness of family therapy—a format in which all members of the household meet together with a therapist. At that time, conjoint family therapy was far more visible than it is today, and I knew at least a dozen therapists in Palo Alto who did family therapy exclusively.

I was treating a patient with ulcerative colitis and asked Don Jackson to be my co-therapist for several family sessions. Together we published a paper about our findings. During my next year I saw several families in therapy, but ultimately I found individual and group therapy more intriguing. I haven’t done any family therapy since then, though I often refer patients to family therapists. Another member of the MRI was Gregory Bateson, the famed anthropologist and one of the theorists behind the “double-bind” theory of schizophrenia. Bateson was a memorable raconteur and held open conversations at his home every Tuesday evening, which I often attended and greatly relished.

Another area that interested me during my first years at Stanford was the field of “sexual disorders,” to which I had been introduced during my residency when I worked with sexual offenders at the Patuxent Institute. At Stanford, I regularly consulted on weekends with sexual offenders incarcerated at Atascadero State Hospital, and for the next several years I saw a number of patients in my practice who were voyeurs, exhibitionists, or had some other form of disturbing sexual compulsion or obsession. I often treated gay men, who, in retrospect, suffered primarily from society’s views of them. I gave a grand rounds presentation at Stanford about some of my work with these patients, and, immediately afterward, a plastic surgeon, Don Laub, in the Stanford Department of Surgery, asked if I would serve as a consultant for a new program he was launching with a series of transsexual patients requesting surgical gender change. (The term “transgender” did not yet exist.) At that time, such surgery was not performed in the United States—patients seeking gender change had their surgery in either Tijuana or Casablanca.

Over the next few weeks the Surgery Department referred about ten patients to me for presurgical evaluation. None of these patients had serious mental disorders, and I was struck by the power and depth of their motivation for sex change. Most of them were poor and had worked for years to save money for the surgery. All were anatomical males who wished to become females: the surgeons were not yet offering the more challenging female-to-male surgery. The Surgery Department enlisted a social worker to lead a presurgical group offering training in feminine mannerisms. I attended one class exercise in which the patients sat at a bar and the instructor rolled coins into their laps and taught them to spread their knees to catch the coins in their skirt, instead of reflexively pressing their knees together as males tend to do.

The project was far ahead of its time but ran into problems after a few months: one of the postsurgical patients became a bottomless nightclub dancer advertising herself widely as a Stanford Hospital creation, and another attempted to sue the hospital for battery after his male genitalia had been removed. The project was closed down, and it was a great many years before Stanford again offered such surgery.

My family’s first five years in Palo Alto, 1962 to 1967, coincided with the beginning of the civil rights, antiwar, hippie, and beatnik movements—all of them radiating from the San Francisco Bay Area. Students inaugurated the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley, and teenage runaways swarmed to Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco. But at Stanford, thirty miles away, things remained relatively calm. Joan Baez was living in the area, and Marilyn once marched in an antiwar demonstration with her. My most vivid memory of this period is attending a huge Bob Dylan concert in San Jose, where Joan Baez unexpectedly came onstage for a few numbers. I became a lifelong Joan Baez fan, and was thrilled, years later, when I had the chance to dance with her after one of her café performances.

Like everyone else, we were devastated by the news of John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. It shattered the image that our peaceful lives in Palo Alto would be unaffected by the ills of the outside world, and we bought our first television set to witness the events surrounding Kennedy’s death and memorial services. I eschewed all religious belief and practice, but in this instance, Marilyn, feeling the need for community and ritual, took our two older children—Eve, aged eight, and Reid, aged seven—to a religious service at the Stanford Memorial Church. Having not entirely escaped the pull of ceremony, we always held a Passover Seder at our home with family and friends. Never having learned Hebrew, I always asked a friend to read the ceremonial prayers.

Despite my unpleasant memories of childhood, I continued to favor the type of food I was raised on: Eastern European Jewish cuisine and no pork. Not Marilyn. Whenever I was out of town, the children knew she would serve them pork chops. I clung to some ceremonial rites. I had my sons circumcised, followed by a ceremonial repast with friends and family. Reid, the eldest of my three sons, chose to have a Bar Mitzvah. In addition to these few Jewish traditions, we had a Christmas tree, filled stockings for the children, and laid out a big Christmas Day feast.

I’ve often been asked whether my lack of religious belief has been a problem in my life or my psychiatric practice. My answer is always no. First, I should say that I am “nonreligious” rather than “antireligious.” My stance was by no means unusual: for the overwhelming majority of my Stanford community and my medical and psychiatric colleagues, religion played little or no role in their lives. When I’ve spent time with my few devout friends (for example, Dagfinn Føllesdal, my Catholic Norwegian philosopher friend), I always feel tremendous respect for the depth of their faith, and I’m inclined to say that my secular views almost never influence my therapy practice. But I have to admit that in all my years of practice, only a handful of committed religious individuals have sought me out. My most frequent contact with devout individuals has come in my work with dying patients, and in every instance I welcome and support any religious comfort they can find.

Though I was deeply immersed in my work in the 1960s and largely apolitical, I couldn’t help but notice cultural changes. My medical students and psychiatric residents began to wear sandals instead of “proper” shoes, and year by year their hair got longer and wilder. A couple of students brought me gifts of their home-baked bread. Marijuana infiltrated even faculty parties, and sexual mores were radically changing.

I already felt part of the old guard when these changes occurred and felt shocked the first time I saw a resident wearing red plaid trousers or other outrageous garb. But this was California, and there was no stopping such change. Gradually I loosened up, stopped wearing neckties, and enjoyed marijuana at some faculty parties, where I, too, wore bell-bottomed trousers.

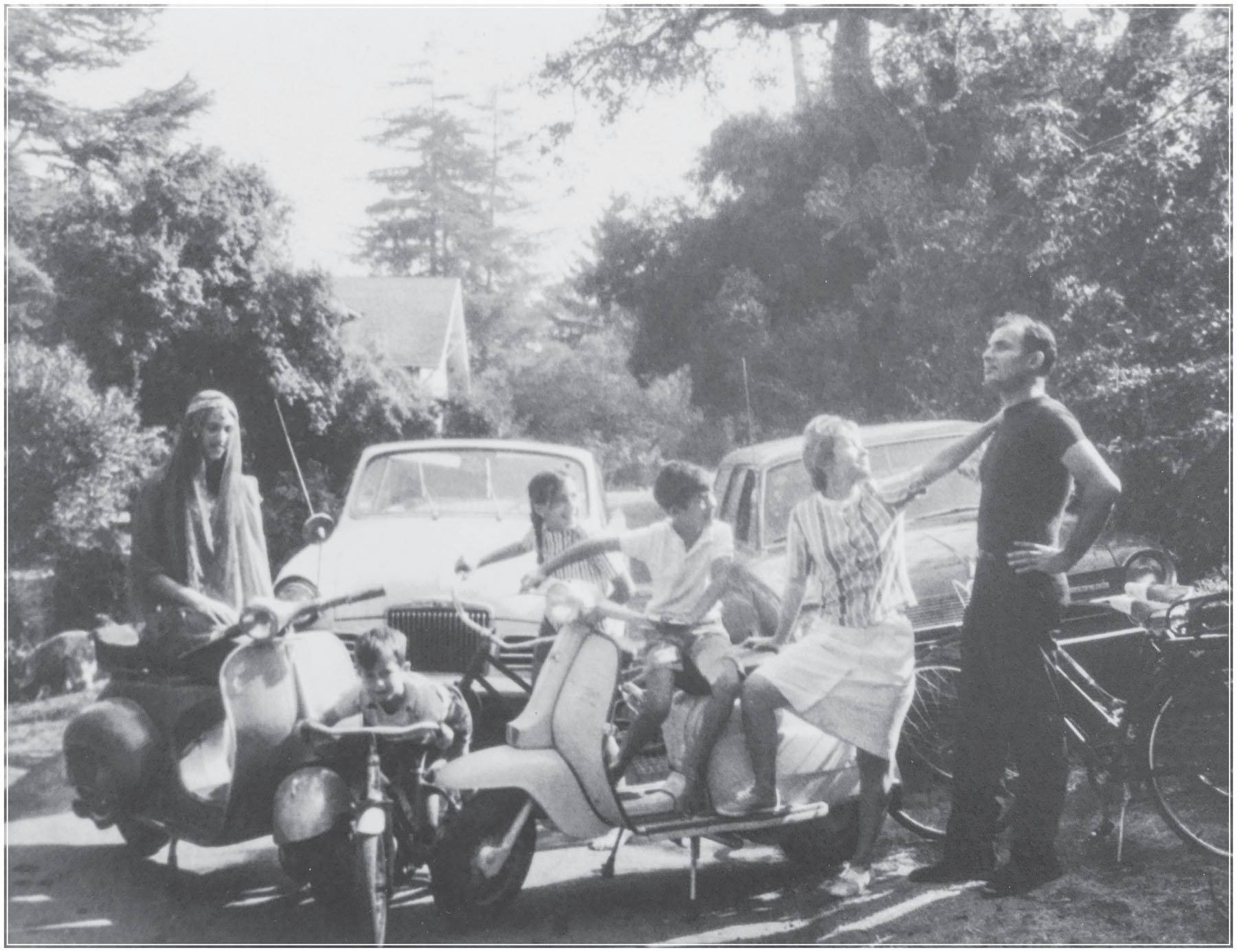

In the 1960s, our three children—our fourth, Benjamin, was not born until 1969—were caught up in their own daily dramas. They attended the local public schools within walking distance of our home, made friends, took piano and guitar lessons, played tennis and baseball, learned to horseback ride, joined the Blue Birds and 4-H, and built a corral for two young goats in our backyard. Their friends from smaller homes often came over to our home to play. Our house was an old Spanish-style stucco with a front door surrounded by bright violet bougainvillea and a patio containing a small pond and fountain. The formal path leading down to the road was dominated by a majestic magnolia, around which the small children rode their tricycles. There was a neighborhood tennis court half a block from my home, where twice a week I played doubles with my neighbors, or, as they got older, with my three sons.

In June 1964, we visited my family in Washington, DC. We were at my sister’s home with our three children when my mother and father drove over. I sat on a sofa with my daughter, Eve, and my son Reid on my lap. My son Victor and his cousin Harvey were playing on the floor nearby. My father, sitting in an adjoining upholstered chair, told me he had a headache, and two minutes later, suddenly and wordlessly, he lost consciousness and slumped over. I could feel no pulse. My brother-in-law, a cardiologist, had a syringe and Adrenalin in his physician’s bag and I injected Adrenalin into my father’s heart—but to no avail. Only later did I remember that just before he passed out I had seen his eyes fixated to his left, suggesting a stroke in the left side of his brain, not a cardiac arrest. My mother rushed into the room and clung to him. To this moment I can hear her crying, over and over, “Myneh Tierehle, Barel” (“My darling, Ben”). My tears flowed. I was astonished and deeply moved: it was the first time I had ever witnessed such tenderness from my mother, the first time I realized how much they loved one another. When the emergency unit came, I remember my mother still crying but saying to my sister and me, “Take his wallet.” My sister and I ignored her pleas, and both of us felt critical of her for focusing on money at such a time. But she was right, of course: his wallet, cards, and money disappeared in the ambulance and were never seen again.

I had seen dead bodies before—my cadaver in the first year of medical school, bodies in pathology courses at the morgue—but this was the first dead body of someone I loved. It would not happen again for many years, until the death of Rollo May. My father’s funeral was held at a cemetery in Anacostia, Maryland, and after the service each of the family members ceremoniously threw a shovelful of soil on the coffin. As I did so, I felt lightheaded, and my brother-in-law caught my arm and steadied me, lest I fall into the grave. My father died as he had lived, quietly and unobtrusively. Even to this day I regret not having known him better. When I’ve returned to the cemetery and walked up and down the rows of tombstones where my father and mother and their entire community from the small shtetl of Cielz lay, my heart has ached for the gulf between me and my parents and all that remained unsaid.

Sometimes when Marilyn describes her tender memories of walks in the park holding hands with her father, I feel bereft and cheated. Where were my walks and my father’s attention? My father worked hard his entire life. His store was open until 10 p.m. five days a week and until midnight on Saturdays: he was free only on Sundays. My only tender memory of time spent with my father revolves around our Sunday chess games. I recall he was always pleased with my play, even when I began to beat him at about the age of ten or eleven. Unlike me, he never, not once, was annoyed by losing games. Perhaps this is the reason for my lifelong engagement with chess. Perhaps the game offers some shreds of contact with my hardworking, gentle father who never got to see me as a more mature adult.

When my father died, I was just beginning my life at Stanford. At the time I don’t think I fully appreciated my extraordinary good fortune. I had a position at a great university, worked with total independence, and lived in a blessed enclave with perhaps the world’s best weather. I never saw snow again (except at ski resorts). My friends, mostly colleagues at Stanford, were easygoing and enlightened. And never once did I ever again hear an anti-Semitic statement. Though we were not wealthy, Marilyn and I had the feeling of being able to do anything we wished. Our favorite getaway was Baja, California, at a colorful if modest location called Mulegé. We took our children there one Christmas, and they fully enjoyed the Mexican atmosphere replete with tortillas and piñatas. My children and I reveled in the snorkeling and spearfishing, which provided several delicious meals.

Marilyn returned to France for a conference in 1964 and wanted very much for the whole family to take a trip to Europe. What turned out was even better: a whole year in London.