3 The Bear of Legend

On a mountain near Vattis, Switzerland in 1917, workmen digging in a cave made an amazing discovery. Here, in the Drachenloch Cave, prehistorian Emil Bächler reported finding among a jumble of rocks and bones, a limestone ‘chest’ or ‘box’ containing a number of cave bear skulls stacked one upon another, all facing in the same direction. Bächler surmised that the ‘chest’ and the arranged skulls revealed human intent. But what was that intent? Was it part of a prehistoric religious ceremony centred on the cave bear?

Did the cave bear serve as a kind of religious or spiritual force prompting such shrines? Could such arrangements of skulls result naturally? Many prehistorians and paleontologists dispute Bächler’s findings and his theory of the existence of an ancient cave bear cult, claiming that there was little contact between early humans and cave bears. Björn Kurtén notes that Bächler contradicts himself in his statements and his drawings of the ‘chest’ of skulls. Kurtén also points out that there were no photographs of the find, nor was Bächler present at the site when the discovery was unearthed. And, finally, workmen destroyed the so-called ‘chest’. Furthermore, Kurtén and others claim that Bächler’s find, and the arrangements of bones in other caves suggesting a prehistoric cave bear cult, could be the result of natural action brought about by falling rocks and the displacement of bones by subsequent cave inhabitants.1

Opponents of the existence of a cave bear cult also dispute that paintings of bears in French and Spanish caves suggest that bears were of religious significance to prehistoric communities. Kurtén points out that the painted bears are, as best as he can tell, brown bears, a smaller species probably in closer contact with humans than the cave bears that roamed at higher altitudes.2

Such reasoning, however, does not convince other prehistorians. László Kordos, among others, feels there is a strong possibility that some spiritual significance was attached to the cave bear by prehistoric humans. In a cave in the Bükk Mountains, he found three cave bear skulls placed in what he believes was an intentional formation.3 Is this evidence that reverence was attached to the cave bear in Paleolithic times, at least in some places? Could these skulls, so carefully arranged, be the result of some ancient ceremony that honoured the spirit of the cave bear? Recent findings in Belgium of cave bear remains spotted with red ochre suggest that early Neanderthal or other prehistoric people did conduct rites utilizing cave bear bones. How extensive these practices were, however, is unknown.4

Long ago bears lumbered into human imaginings and left legends, stories and myths, which gave rise to ceremonies, rites and observances. In the ring of forest, tundra and Arctic coast that encircles the pole in the northern hemisphere, stories and attitudes about bears were remarkably similar in early times, and many of these ancient tales and practices continue today in certain areas. There, bears were respected not only for their strength and physical power but also for their sacred power. Other important attributes deserving of respect were kinship with humans, comprehension of human speech, assuring successful hunts, providing cures, and offering spiritual protection. In pre-agricultural Finland, bears were honoured as masters of the forest.

Over the millennia, stories told and retold in smoky forest huts spread among cultures in these cold lands of snow and dark forests, permitting people to conceptualize bears, give them meaning and endow them with mystery. The oral tradition passed from one generation to another began to weaken in most parts of the world five or six centuries ago but stories and songs, although fragmented now, remain sources of information for ethnologists and folklorists. They are more than just amusing tales. They are literary sources that offer valuable information on kinship relations and old customs and beliefs. Stories about bears constitute a large percentage of the mythic literature and reveal how people in the past imagined the bear. Some stories have spread thousands of miles in multiple versions and have even crossed from one continent to another. Among the Native Americans, stories were told at night, generally in the winter, across a warming fire or in some ceremonial-defined context. They were didactic, told to educate children and remind adults of how the world came into being, what the role of the bear was in creation, and what might happen if taboos were ignored or bear hunting rites improperly performed.

Native American Indians hunting a bear, in a lithograph after the celebrated Western artist George Catlin. |

|

The bear was the most powerful animal spirit, and to anger this spirit could prove extremely dangerous. But there was another reason for the extreme respect paid to the bear spirit. As anthropologist A. Irving Hallowell noted, among people in the northern hemisphere, ‘the bear was believed to represent, or was under the spiritual control of some supernatural being or power which governed either the potential supply of certain game animals, or the bear spirit alone.’5 That is, many believed that the spirit of the bear either controlled all the bears or all the animals. The spirit could release them for human consumption or, if angry, hold them back. If the latter, people would starve.

Since bears could understand what humans said, humans were careful not to refer to the bear directly but employed euphemisms to represent it. The Navaho referred to it as ‘Fine Young Chief’, while among the Koyukon of Alaska it was called the ‘Dark Thing’. The Khanty and Mansi of Central Asia used several terms, including ‘Swamp Darling’, ‘Old One of the Forest’, ‘Darling Old One’, and ‘Sacred Animal’. The Finns’ terms included ‘Master of the Forest’ and ‘Pride of the Woodlands’, while the Yukaghir, a people of northern Siberia, refer to the bear as the ‘Owner of the Earth’. Common to all is the resonance of spiritual power, strength and control. In ancient Finland, bears were believed to be kind to man unless talked about and called Karhu, today the Finnish word for bear. Then they grew angry and brought harm to humans. Apparently bears much preferred to be called ‘Grandfather’ or ‘Forest’, since they considered themselves the kings of the forest. According to the Finns, before man came to the woods there was no creature that dared to defy old ‘Forest’. No one dared to call him Karhu. He was the forest itself and when he moved the forest moved with him.6

A Finnish bear-head stone club from the second millennium BC, thought to be a weapon with possible ritual uses, reflecting the centrality of bears to prehistoric Finnish culture.

For pre-agricultural peoples, the meaning of the bear was rooted in their worldview and their environments. The stories that follow address these worldviews and in so doing give cultural meaning to the bear.

Among the Modoc of California there is a story of the creation of the grizzly bear and of Native Americans and the kinship between the two. It is also a story of the bear as protector and nurturer of humans.

One day, the chief of the sky spirits was walking in the above world and grew annoyed by the cold there. Making a hole in the above world, he pushed all the snow and ice through it until it formed a mountain from the earth below almost to the sky. The chief then stepped through the hole and walked down the mountain. The scene was bleak and devoid of life. Wherever he touched his finger to the mountain a tree sprung up. At one point the chief of the sky spirits picked up a branch and, breaking it into pieces, threw the large pieces into a river at the base of the mountain. There, these large pieces of wood became beavers and the little pieces became fish. From some of the large pieces of the branch, he made grizzly bears. They were large, covered with thick hair, had long, sharp claws and walked around on their hind two legs. The chief of the sky spirits thought they were incredibly ugly and ordered them to live at the bottom of the mountain.

The chief of the sky spirits then looked around and decided he was pleased by the mountain and the world he had created and decided to bring his family down to live in a lodge that he built inside the mountain. The entrance to the lodge was through a hole in the top of the mountain that also served as a smoke hole. One day, when the chief of the sky spirits sat with his family around a roaring fire inside the mountain, the wind spirit blew up a storm. The wind grew so strong that it blew the rising smoke from the fire back into the mountain. This annoyed the chief of the sky spirits, and he asked his little daughter to go to the smoke hole and tell the wind spirit to blow more gently. But the chief also warned his daughter not to put her head out of the smoke hole because the wind might catch her hair and blow her away. She did as instructed but was unable to resist putting her head out of the smoke hole a little way in order to take a look around. That was enough for the wind spirit who, as her father had warned her, grabbed her hair, lifted her out of the smoke hole and tumbled her down over the snow and ice to the bottom of the mountain.

A grizzly bear out hunting found her and carried her home to his wife. The wife, feeling sorry for the little girl, took her in and raised her along with her own cubs. When the little girl grew to womanhood, she married the eldest son of the grizzly bears and in time had many children. When the mother grizzly bear grew old, she began to feel guilty about keeping the daughter of the chief of the sky spirits away from her home in the mountain. She told one of her sons to climb the mountain and tell the chief of the sky spirits that his daughter was alive and where she could be found. The chief of the sky spirits was delighted with the news that his daughter was still living and he hurried down the mountain to see her. He found his daughter living with the grizzly bears and taking care of a brood of strange-looking creatures who he learned were his grandchildren. What he saw greatly angered him. A new race of creatures had been created. In revenge, the chief of the sky spirits cursed all grizzly bears, telling them that from that time forth, they would all walk on four legs and would never be able to talk or use language again. He then took his daughter and carried her back up the mountain and perhaps up into the sky. The strange creatures, half grizzly and half spirit people, travelled far and wide and, according to the Modoc, were the first Native Americans and the ancestors of all the tribes.7

In this tale, one learns not only about the creation of grizzly bears and Indians (Indians who tell these tales see themselves as distinct from other peoples), but how similar the first bears were to humans: walking on their hind legs, speaking and living in formal married relationships. They were the progenitors of the tribal peoples of America. To this day, there are some tribes that refuse to eat bear meat since to do so would be to eat their own ancestors. Other tribes have their own creation stories. These generally fall into two types: people emerging out of the earth, or descending from the sky. The Modoc tale is a variation of the sky origin myth, while a tale from the Menominee of Wisconsin, who also see their origin connected to the bear, have the bear emerging from a hole in the earth. The Modoc tale is only one of many Native American creation stories in which the bear figures prominently.

In another bear creation story, the culture hero Väinämöinen sings of the creation of the bear in the great Finnish epic, the Kalevala. From a piece of wool thrown on the waters by a female air spirit, the bear is given birth. But the bear is not born at once. The wool is ‘lulled’ and ‘wafted’ upon the waters until it is washed ashore. There, Mielikki, the forest mistress and wife of Tapiloa, the lord of the forest, gathers up the wool, lays it in a basket and tends it until the wool is slowly transformed into a bear.

The Beast grew beautifully

came up to be most graceful—

short his leg, buckled his knee

a chubby smooth-snout

his head wide and his nose snub

his fur fair, luxuriant;

but yet he had no teeth

nor had his claws been fashioned.

But Mielikki, forest mistress, proclaimed that she would ‘fashion claws for him, teeth too ... if he were to do no harm and get up to no mischief’.8

The Kalevala relates the birth of the bear from sky and water. The bear has the same origins as the culture hero Väinämöinen, who also achieves form through the agency of a female air spirit, floats upon the water and is later, like the wool that gives birth to the bear, blown to shore. Hence a case could be made that through the stark similarity of their origins, the bear and Väinämöinen are brothers. The bear is intricately coupled to Finnish history and to the Finnish people.

Among the Mansi, a Finno-Ugrian people of Central Asia, the bear originated in heaven. One version holds that the first bear was an unruly son of the sky god, Kores. One day on catching a view of the earth the young bear demanded that his father allow him to visit. Finally, his father acceded to his son’s wishes and made a cradle of gold and silver coins suspended on iron chains. On the first two tries, when dropped from heaven, the cradle carrying the bear swung in all directions but did not reach the earth. On the third try the cradle reached earth, landing in the middle of a forest swamp. Before leaving heaven, Kores gave the cub specific instructions: not to touch the sacrificial huts, not to disturb human corpses, and not to harm human beings. He also instructed the cub to eat fruits, especially berries. But the young bear grew bored with life on earth. The summer was hot, with lots of mosquitoes and few berries. The bear destroyed the sacred huts of the people and in winter ravaged frozen corpses in their coffins. Eventually he was killed by hunters who marked the death with ceremonies that allowed the bear’s spirit to return to the sky, its proper home.

Important here is the belief in the cyclical nature of the bear’s passage, perhaps inspired by its hibernation cycle: it comes from heaven, is killed, and returns to heaven only to come back to earth again.9 Variations of this tale can be found among the Gilyaks and Ainu peoples of northeastern Asia.

One of the most universal tales – versions are found from North America to Siberia – is the legend of the woman who marries a bear. With such an extensive geographical range, this tale may be thousands of years old. This version is drawn from the Haida culture of British Columbia. The story relates how a group of women encountered bear droppings at a place where they went to pick berries. Ignoring warnings that it was taboo for women to step over such droppings, one young woman not only stepped over them but on them and kicked them. At the same time she hurled insults at bears and mocked them in derisive language. In the afternoon, when her friends returned home, the young woman decided to remain a while longer, having discovered a bush laden with berries (other versions have her spilling her basket of berries and having to pick them up, thus preventing her from returning to the village with her friends). As she picked, she noticed a handsome young man approaching wearing a bear skin cloak. He offered to help her pick berries and told her of other bushes with even more berries further up the mountain. He suggested that they pick them and he would walk her back to her village. It soon grew dark and the young man said it was too late to return to her village and suggested that they should make a camp and return to the village the next day.

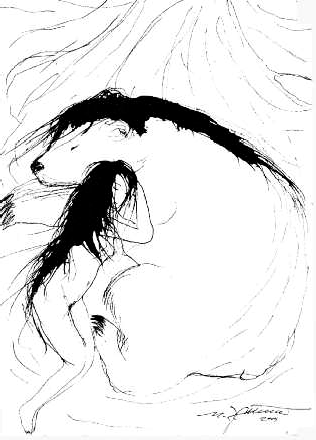

Winter Sleep by Finnish artist Helena Junttila echoes many folkloric stories of bear–human couplings. |

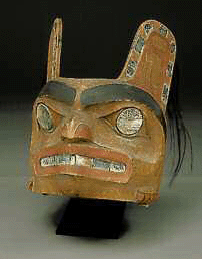

A Tlingit bear mask, from the Pacific northwest of Canada.

Haida tunic with bear motifs comprising shells and shark teeth, from the Pacific north-west of Canada.

On the following day, as they continued to pick berries, the young man used his shamanistic power to make the woman forget about going home. Days turned into weeks as the man led the woman further and further from her village to pick more berries. Finally, when summer passed into fall and it began to grow cold, the man decided he would dig a den, and the woman’s suspicions that he was actually a bear were confirmed.

That winter the woman gave birth to two children, half human and half bear. In early spring her husband awoke suddenly from his sleep of hibernation and announced that someone was coming. The woman knew that her brothers were searching for her. Several times her husband awoke and each time he said, ‘They are getting closer.’ Then her husband said, ‘They are almost here; I will put in my teeth and kill them.’ The woman pleaded with him, telling him that what he heard were her brothers coming to find her and she begged her husband not to kill them but to let her brothers kill him for the sake of their children. He finally agreed but told the woman that upon his death certain rites were to be performed and songs sung.

Encounter (2001) by Helena Juntilla evokes northern European stories of women’s relationships with bears.

A Haida carving of a mother nursing a bear cub.

After her husband, the bear, was killed and the rites performed and the songs sung, the woman, with her two half-bear, half-human children, returned with her brothers to the village. Fearful of turning into a bear herself, she refused to enter into games with them that involved wearing a bear’s skin and pretending to be a bear. But in defiance of her wishes, one brother threw a bear skin over her and her two children. As she had feared, she and the children immediately turned into bears. She then killed her brothers and returned to the woods with her cubs.10

This story, like most tales, can be interpreted at various levels. Most obvious is the lesson that, if taboos are broken, social order breaks down and disaster follows. At another level, it is a story about anger and revenge, the bear’s ability to change shape, to communicate in human speech, and to interbreed with humans. It is this last power that instigated fear and anxiety among women in the northern hemisphere, causing them – at least the unmarried women – to maintain a safe distance from dead bears brought in from the hunt. Women were also not allowed to eat meat from the front of the bear, only from the rump. The reason, according to some stories, is that it is the front side or front legs that do the embracing.

An early tale from Scandinavia, recorded in 1555 by the Archbishop of Uppsala, Olaus Magnus, in his Description of the Northern Peoples, told of a beautiful young girl abducted by a bear and taken to his cave. Although he stole her to ‘tear her to pieces’, he soon fell in love with her and ‘he now altered his designs on her to purposes of wicked lust. He immediately turned from robber to lover, and dispelled his hunger in intercourse, compensating for a raging appetite with the satisfaction of his desires.’ To encourage the girl’s affections he robbed local farms and brought her fruits and other food ‘spattered with blood’. Eventually, the farmers of the region tired of the bear’s stealing, found his cave, and killed him with dogs and spears. The pregnant woman was now free but, ‘Nature working with two different materials palliated the unseemliness of the union by making the bear’s seed suitable. The girl gave birth normally but to a marvel among offspring, lending human features to this wild stock.’ The child, a boy, while looking human, had the wildness and strength of the bear and slew those who had killed his father. From this boy descended King Sven of Denmark and a long line of Danish kings.11

Snaps by Heinrich Kley gives bear folklore a modern twist. |

There are many tales throughout the northern hemisphere of women abducted by bears and forced to serve as wives and beget children. Sometimes this has political and/or social consequences as the progeny serve as the origin of a lineage or clan. In some tales, males are abducted and forced to serve as husbands. In parts of South America there are legends of spectacled bears stealing both virgin girls and unmarried boys. The long cross-cultural obsession with women and bears is curious and continues to this day. In many parts of the world women are sexually identified with bears. Some even describe themselves as ‘bear women’ who have descended from bears in the same way as certain aristocratic families in the past claimed their own origins.

Helena Junttila’s painting Bear Lisa (1999) gives the bear a gentler face. |

Another gentle bear, this time in California. |

Bears did not always prey upon humans. Sometimes they were exploited by humans, as in this Inuit story from Greenland.

Once, an old couple beyond childbearing age wished for a son. One day the man killed a polar bear and sang a song to it, pleading it to come back to life and be his son. Out of the blood flowing from the dead bear emerged a bear cub. The couple were happy and raised it as their own. When the bear-son grew older, it hunted for the old couple, bringing them harbour seals, ringed seals and other meat. They were happy to have such a good hunter as a son. Then one day the old man asked his bear-son to bring back the meat of an ice or polar bear. Although the bear-son refused, since he did not want to kill his relatives, the old man insisted. Finally the bear-son, out of a strong sense of duty, went forth and later returned with the body of a large she-bear, but when the old couple sat down and began to eat the bear meat, he walked out, never to return. The old couple, left without their bear-son to hunt for them, soon died.12 Here again the strong kinship connection between bears and humans is demonstrated and also the moral that abusing that kinship relationship can result in tragedy.

A Cherokee bear mask from the southeastern United States. |

|

For many people around the northern rim, bears possessed remarkable powers: not only could they change shape, they could also come back to life. Perhaps the bears’ emergence from their dens in the spring after a winter under ground came to symbolize this resurrection ability. The following tale from the Cherokee of the southeastern United States speaks of this life-renewing capability.

One day a hunter chanced upon a bear and shot an arrow into it. The bear began to run and the hunter gave chase, all the while shooting him with more arrows. Eventually the bear stopped and, pulling the arrows from his body, confronted the hunter, saying: ‘It is no use for you to shoot arrows into me; you cannot kill me. Let us go to my home and we will live together.’ The hunter grew frightened, thinking that if he did so perhaps the bear would kill him. The bear, however, read the hunter’s thoughts and assured him he would be in no danger. The hunter’s next thoughts were of food and what he would eat, for he was very hungry. Again, the bear read the hunter’s thoughts and told him that he had plenty of food and that the hunter was welcome to it.

So the hunter followed the bear and eventually arrived at his cave. Once inside, the man again thought about his hunger. The bear responded by rubbing his belly and producing nuts, berries and acorns, which the hunter ate until he was full.

The hunter and the bear lived together for nearly a year when suddenly, to the hunter’s surprise, the bear said that people from a nearby village would soon come and kill him. He also told the man that after they had done this they would skin him and chop him into pieces. The bear asked the hunter first to cover his blood with leaves and then, as he was being led away back to his village, to look back.

A Cherokee wood carving of bears and cubs in the wild. |

In a few days, as the bear had prophesied, men came with dogs, found the cave and called for the bear to come out. When he did, he was killed, skinned, and chopped into pieces to be taken back to the village. As this was being done, the dogs continued to bark and the hunters thought there must be another bear in the cave. They soon discovered a man inside and recognized him as the person who had disappeared from the village the year before. But before leaving the man did as the bear had requested: he covered the blood with dry leaves. As the man left for the village with the hunters, he turned to look back and saw the bear rise up from the leaves, shake them off and walk slowly back into the woods.13

The Mansi of central Siberia also tell a story of transformation, but this time about a human becoming a bear. A young boy was lost in the woods. As he sat on a tree stump wishing to return home, he cried, ‘Where shall I see the kin begotten of my father, the kin born of my mother?’ At this moment he tumbled from the stump and upon getting up discovered he had turned into a bear. The transformation gave him new confidence and he sang: ‘Upon the heath I am the true-born son of the goddess who dwells on the heath down in the forest. I am the true-born son of the goddess who dwells in the forests; I am one who lives by his own will.’ In a fit of hubris, he proclaimed he would take whatever God had not granted him.

The Samoyeds and the Lapps also told stories of metamorphoses but, as we shall see later, they ‘also practised rites believed to change themselves, or others, into a bear or to change a bear into a man.’14

The powers of the legendary bear, however, were greater than warding off arrows and reincarnation. They also extended to curing. Among the Lakota (Sioux) Indians, when effecting cures, ‘bear doctors’ would sing, ‘My paw is sacred, the herbs are everywhere. My paw is sacred, all things are sacred.’15 The Native American ‘pharmacopoeia’ was replete with plants they derived from watching bears collect herbs, berries and roots. According to many tribal accounts, one only had to watch what the bear ate to learn what plants were beneficial to human health. Among several of the California tribes, a group of shamans also known as bear doctors were highly respected as healers. They allegedly received their healing powers from bears. The following tale from the Hupa Indians of California is only one story of bears’ medicinal powers.

One day, while walking in the world, a bear became pregnant. The more she walked the fatter she became and soon she was too fat to walk. At this point she began to consider her position and wondered if Indians also got in this way; that is, pregnant. Suddenly, from behind her, she heard a voice saying, ‘Put me in your mouth; you are in this condition for the sake of the Indians.’ When the bear turned round she saw a plant of redwood sorrel. She put the plant in her mouth and the next day she could walk again. So she thought, ‘It will be this way in the Indian world with this medicine. This will be my medicine [to them]. At best not many will know about me. I will leave it in the Indian world. They will talk to me with it.’16

‘Ursa Major’ (the Great Bear), a hand-coloured etching from Aspin’s 1825 Familiar Treatise on Astronomy.

To some, the bear also held the responsibility for the change of seasons. Since it entered its den in the fall as the days grew short and emerged again in the spring as the days lengthened, it was believed that the bear controlled the sun. The bear that seemingly died in the fall, burying itself under ground when darkness and the cold of winter covered the earth, returned from the underworld in spring bringing the sun and longer days as he once again began to roam the earth.

Although not all cultures that honoured bears believed they controlled the sun, many saw the bear as a celestial figure in the night sky. The Great Bear, season after season, slowly circled the Pole Star in a never-ending journey. According to the Mesquakies, or Fox Indians, of the American Midwest, its heavenly travels resulted from a hunting trip gone terribly wrong.

Long ago, according to Mesquakie legend, three brothers decided to go on a winter hunt for bears. One brother took his dog along to help in the hunt. Eventually, after walking through woods and brush, they discovered a bear’s den. One brother entered it to drive the bear out. He found the sleeping bear and poked it with his bow until the bear awoke and ran outside. The bear managed to elude the brothers waiting outside but they then gave pursuit. The bear ran first to the north and then to the east and then to the west. The brothers looked down and saw the earth far below and shouted that they should turn back. But it was already too late for they were in the sky. To this day, according to the Mesquakie, the brothers and the dog chase the bear around and around the Pole Star. Until they catch the bear, they can never rest.17

Like the peoples of North America and Siberia, the ancient Greeks saw the Great Bear prowling the night skies and attributed its wanderings to the activities of Callisto and Zeus. Callisto, the daughter of Lycon, King of Arcadia, the place of the bear people, was one of the young women who attended Artemis, the protector of wild things and children. One day, Artemis discovered that Callisto was pregnant and as a punishment turned her into a bear and expelled her into the heavens. Another version of Callisto’s downfall centres on Zeus. Hera, the wife of Zeus, angry that Zeus had made Callisto pregnant, turned her into a bear after her son was born. When the son, Arcas, grew up, Hera sought to have him kill the bear that was his mother. But Zeus intervened, snatching Callisto away and placing her among the stars as the constellation Great Bear or Ursa Major.18

A modern bear effigy from the American Southwest.

|

Very early Native American carved stone bear effigies, from Alaska. |

In the lands of forests and lakes and in the Arctic where cold winds sweep over ice packs and tundra, bear legends depicted them as sacred, strong and possessed of powerful medicine. Of all animals in the north, the bear was the most human. Bears were respected partly because of their kinship with humans and also because they were feared. The bear held important knowledge and could bestow blessings or wreak tragedy.

As hunter-gatherers gave way to agriculturalists, the image of the bear in stories changed. Of course, in pre-agricultural times, narrators often took liberties in presenting tales. Depending on the context in which the tale was told, or the creative nature of the storyteller, the story might alter slightly but the symbolic meaning of the bear remained constant. This all changed, however, in a new world devoted to herding and agriculture. The bear became seen as an impediment to progress and was desacralized, made to represent an ogre or a fool, and marked for destruction.

Bears were turned into stupid, menacing brutes or threats to agricultural life. According to Olaus Magnus, bears enjoyed music so much that they terrorized shepherds, often carrying them off after being attracted by the music shepherds played on their pipes. Blowing horns, however, forced the bears to release their victims, for the noise annoyed them and sent them running off back into the woods.19

One can find similar stories of outwitting bears in Russian folk tales such as ‘The Peasant and the Bear’ and ‘The Bear and the Cock’, where the bear is played for a fool. In more recent children’s stories, some of which have tenuous roots in earlier folk tales, the bear is depicted as a clown, a simple, good-natured figure such as Baloo in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book, or else a vengeful creature as in early versions of The Three Bears, where an intruder breaks into the home of the three bears, eats porridge and sleeps in a bed. In one version, the intruder is an old woman whom the bears catch. They attempt to kill her by burning and drowning. When these fail they throw her up in the air where she becomes impaled on the steeple of St Paul’s Cathedral. In the more popular version, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, the bears discover a little girl in the house and although they chase her, she escapes their wrath. Even Leo Tolstoy’s version of The Three Bears carries this vengeful element when the small bear that catches the girl sleeping in his bed chases her with the intent of inflicting punishment.20 Post-agricultural tales generally represented bears in negative terms that applauded their disappearance. It is only now, when bears are marginalized and pose no threat to common daily life, that they have been invested with a gentler demeanour.

Stories help us to understand the world and our place in it; they help us to imagine ourselves. According to some scholars, the stories, ceremonies and rites relating to bears ‘allowed the community to see the coherence of its central economic, social and religious values and to reaffirm their significance’.21 The French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss once observed that animals are good to think with.

The cover (c. 1910) of one of the many early versions of the story of The Three Bears. |

The ancient Greeks believed that bears were born formless and the mother licked them into shape – not unlike the role of education in human society. Stories served to shape bears’ relationship to humans, giving them not only meaning in the world but a history, too. Across the northern hemisphere, the world of most of the Ursidae family, stories of the ‘Dark One’, the ‘Owner of the World’ and the ‘Wandering One’ were told.

A mother bear licking her newborn into shape, from a 12th-century bestiary. |

As we have seen, stories across vast distances were remarkably similar. Is this because of the similarity of environments or because the human mind grapples in similar ways to explain the behaviour and characteristics of bears? Or does it indicate that at some time in the human past the cultures out of which these stories emerged were connected, over time drifted apart yet carried the stories and the archetypical bear along with them as cultural baggage, as Hallowell suggests? As with so many questions about these wonderful animals, we may never know.