4 Bears and Humans

Recently in Finland, a man out picking blueberries looked up to see a female bear with two cubs wander into the clearing. Frightened, he immediately froze, then cautiously backed away and stood by a tree. The bear slowly approached, sniffed him up and down and then licked his face before moving on. Many Native Americans and perhaps some ancient Finns, too, would have seen in this incident a kind of spiritual encounter; an expression of kinship. The man’s reaction, however, was to go for his gun. Fortunately for the bear, the man, after finding his gun, could not find the bear. Yet the incident, although ending well for both man and bear, prompted Finnish hunting groups to call for an extended bear-hunting season in order to teach them to fear humans. Bears, however, have already learned to fear humans and, as many bear watchers believe, seldom attack unless they feel threatened, are extremely hungry, or are protecting cubs.

Humans and bears have walked together out of history. We were together in those caves in southern France and in Spain. Over the centuries we have dined on each other. Until the agricultural revolution, our need for the bear was greater than the bear’s need for us. Humans have called on bears for warmth, food, medicine, power and protection. An aura of sexual attraction between humans and bears has long existed in legends, as we have seen. In Egypt, it is related that a great white bear prowled the court of Ptolemy II (285–246 BC). ‘On special occasions the beast was paraded through the streets of Alexandria, preceded by young men who carried a 180 foot phallus.’1 Humans have used bears as the symbolic roots of their lineages and clans and to communicate with gods.

Only in a few cultures are bears still seen as kin or as spiritual entities with special bonds to humans or semi-sacred creatures who possess great powers. Now, devoid of their sacredness, most societies regard them as objects in a crowded human landscape or as a potentially dangerous nuisance, to be controlled or exploited for human ends.

The shift came, as suggested in the last chapter, when humans ceased being hunters and gatherers and became herders and farmers. Yet the transition must have been gradual, helped along by the growing influence of the Christian Church in northern Europe. In Greece, bears were said to be the most mysterious of all the wild creatures and it seems they possessed a sacred status. In Rome, they were exploited for entertainment and sport in the Colosseum. Once the Roman armies had conquered the Alps, they turned their attention to the Germanic tribes. In between battles, a growing trade in bears sent a steady stream of them into Rome. Many more arrived from Britain (including what is now Scotland), Syria, Greece and, perhaps, northern Africa.2 Some became pets, some found their way into private menageries, while others were forced to participate in bloody entertainments for the delight of a gleeful Roman public.3 Here bears were pitted against lions, bulls and even men. The Emperor Caligula (AD 12–41), for example, had 400 bears killed in a single day in combat with gladiators and other animals. Other Roman emperors treated the populace to similar spectacles, beginning as early as 168 BC.4

Bears represented power; a raw force. In Scandinavia and throughout the north ancient legends and customs lingered, and the transition to a new representation took longer than in southern Europe. Among the Finno-Ugrian people the bear was half-human. Even today among the Mansi and Khanty, a Finno-Ugrian people of Central Asia, the bear is an important animal that exhibits human traits, including the consumption of a wide variety of foods, the ability to walk upright, masturbation, similarity of faeces, footprint, physical shape, facial expression and tears.5 Among the Finns and Lapps, the killing of a bear entailed several days of intricate ceremonies. ‘Of all animals the bear was the object of greatest veneration.’ It was their ‘totemistic ancestor’, ‘the son of the sky god’.6 For the Khanty and Mansi, the bear’s proper home was the sky but it frequently visited the earth.7 To swear on the bear or to take a ‘bear oath’ was the most powerful and binding oath of all.

This reliance on ancient legends is seen in an account written by Pehr Fjellström, a priest in northern Sweden in 1755, who described a Lapp bear hunt. The Lapps traced a bear to its winter den and then, by means of dogs, smoke and flooding, forced it out. Although the process was cruel, the Lapps maintained a profound respect for the animal. Upon returning with the dead bear, several rites were performed. Its skin was saved, the meat was completely used and the bones, after arranging them as in life, were buried. The hunters were prohibited from sleeping with their wives for several days after the hunt and the women could only view their husbands through rings and bracelets. To do otherwise would anger the bear and jeopardize future hunts.8

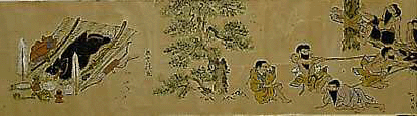

An account from Greenland, dated around 950 AD, records how a great white bear ravaged a village near the home of Eric the Red, the famed founder of the Greenland Norse community. Finally the bear was killed and its meat divided among a rejoicing population. Only Eric the Red expressed remorse, not for the killing of the bear or the distribution of the meat, but because the bear was killed without the old ceremonies.9 Within the last hundred years, hunters in Finland, Siberia and among the Ainu in Japan were solicitous of bears and extremely careful about how their actions would be interpreted by those they killed. The Finns and the Siberian Ostyak tribesmen, who live east of the Urals, would not only address the bear and give thanks but would attempt to blame the killing of the bear on someone else. Both the Finns and Ostyaks would tell the bear that Russians had killed it so as not to implicate themselves. As among many Native American tribes, people in Scandinavia and Siberia held the belief that bears, even though they appeared dead, remained conscious of what went on around them for hours and perhaps even days after they had been killed.10

For the Ainu, the aboriginal inhabitants of Japan, the bear was still of vital importance, and the bear hunt a matter for ritual and ceremony. A 19th-century handscroll, Local Customs of the Ainu, shows scenes from ‘Iyomante’, the Ainu bear ceremony.

Vikings held the bear in high esteem as a powerful, unstoppable force. So potent was the bear’s spirit that waving a bear skin in battle guaranteed protection. Some Norsemen took to wrapping themselves in bear shirts or skins in the belief that the bear’s power and strength would flow into them during battle. Such warriors, called berserkers (from ber ‘bear’ and serkr ‘shirt’), were particularly feared by the enemy. Some believed that at critical moments in battle such warriors became shape-shifters’ and actually turned themselves into bears. In Old Norse sagas, warriors sometimes engaged in hamfarir or shape journeys, sending their spirits in the shape of an animal, generally a bear, to fight in their place. Norwegians used to believe that Lapps and Finns, at moments of great rage, turned themselves into bears. In other accounts, it sufficed to have a bear painted on one’s helmet or shield to evoke the spirit and power of the bear. In England, because of the bear’s power, ‘It was a common practice for aristocratic families in the tenth and eleventh centuries to trace their lineage to bears, as did the earl of Siward, the earl of Kent, Guy of Warwick and the earl of Leicester. Indeed, King Arthur, the leader of the Knights of the Round Table, is connected by name to the bear. Arthur in Latin is Arcturus, ‘bear’. Svend Estridsen, the eleventh-century king of Denmark, also marked his descent from a bear.11

As agricultural pursuits took hold in Europe and spread north, the bears’ forest domain was cut down and their symbolic power ebbed. The growing influence of the Church chipped away at their spiritual reputation. Some have pointed to God’s injunction to Adam and Eve to ‘go forth and multiply’ and ‘have dominion over all the creatures of the earth, air, and sea’ as the inspiration for the Church to ‘desacralize’ animals. Recent scholarship, however, has cast doubt on this, noting, ‘More important was the church fathers’ desire to reject classical Greek and Roman ideas.’ In an attempt to separate Christians from pagan beliefs and establish a new identity for them, early Church Fathers repudiated the ‘classical view’ that saw humans and animals as closely related.12

During the Middle Ages, with prodding from the Church, the belief developed that animals had a fixed nature and no amount of training could alter that fact. Thus animals could serve as didactic symbols in paintings, sculptures and wood carvings. In medieval churches, animal images were often used to drive home moral lessons or illustrate character traits – the cunning fox, the brave lion, the voracious wolf and the strong but stupid bear. The bear, of course, could be raised to extreme violence but preferred to spend its time sleeping. Often in the misericords, carved into the bottom of medieval choir stall seats, the bear appears stupid or just waking up. The image is of a creature of great strength but also of sloth and clumsiness.

A 14th-century English carved-bear misericord from St Hugh’s Choir, Lincoln Cathedral. |

When it came to representing bears, the Church held contradictory views. The doltish image of the bear did not erase the potential for danger wrapped in that shaggy coat of hair. Aroused, bears still possessed a ferocious nature. Hence, St Ursula (her name signifies ‘bear’), acquired her name when she protected her 11,000 virgins with the fury of a bear. Besides Ursula, other saints became associated with bears, gaining their reputations by overpowering the bear’s violence with spirituality. St Sergius of Radonezh, reputed to have power over animals, tamed bears through sharing his food with them. St Gall used bread to tame a bear and taught it to fetch wood for a dwelling. Such holy power is illustrated again in the story of St Korbinian (Corbinian), who, on his way to Rome, lost his pack-horse to a bear attack, whereupon the saint forced the bear to carry the load.13 This story is also attributed to St Claude. These stories are significant for the laity since they confirm the power of the Church not only to tame bears but also the chaos the wilderness represented. An added moral is that if bears can be made docile by the Church, so can the fearful pagan.

For the Church, the bear exhibited other attributes. St Damian reminded people of the bear’s lustfulness when he claimed that Pope Benedict was turned into a bear in the afterlife because of his carnal activities on earth. But if the bear was lustful or fearful, he was also caring and exhibited extreme piety. Indeed, ‘the bear is the first animal in Christian tradition to be called “brother”, because he cares for those in trouble.’14

In other cases, bears became associated with saints by accident. St Blaise became identified with bears because he was the patron saint of Candlemas, a holy day which occurred around the time bears emerged from winter hibernation. In popular belief, the saint and the bear were connected and associated with the beginning of spring. In some parts of eastern Europe, Candlemas was also called Bear’s Day.15

Although the bear became gentle and devout in the hands of saints, most of the population of medieval Europe, living on the edge of the wilderness, lacked the saints’ ability to convert wild bears into passive, obedient creatures. For them, bears remained wild and destructive forces, best exterminated. Paintings depicting bear hunts from the thirteenth to the nineteenth century attest to the threat many believed they posed to society. The same was true in other parts of the world. Holy men may have possessed the power to transform bears into affable fellows but the general population, who had to contend with their destruc-tiveness in gardens, fields, orchards and barnyards, saw bears very differently.

Many of the traits the Church associated with the bear between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries were replicated in the bestiaries, or books of beasts, that circulated widely throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance. The Physiologus, forerunner of the medieval bestiaries, originated as early as the second century AD in Alexandria. Later translated from Greek into Latin, it described about 40 animals employed as moral object lessons. The Physiologus and later bestiaries, however, were ‘never meant to be read as works of natural history’ but rather ‘interpreted the world in a moral and physical sense in order to introduce its readers to the Christian mysteries’.16 As one scholar notes, animals were moral entities, each ‘bearing a message for the human’.17

By the thirteenth century, such books were handsomely produced and very popular among the elite. Their mission was to ‘redefine the natural world’.18 Since most of what those authors wrote was garnered from earlier bestiaries or from oral tales, much of what they said about animals proved wrong. The bear in bestiary manuscript 764, written between 1220 and 1250, in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, is an example. It begins, ‘The bear gets its Latin name “Ursus” because it shapes its cubs with its mouth from the Latin word “Orsus”. For they are said to give birth to shapeless lumps of flesh, which the mother licks into shape’,19 – just as the Church promoted spiritual shaping.20 These ideas probably permeated down from the ancient Greeks. The great German cleric and natural historian Albertus Magnus, however, would have none of this nonsense of cubs being licked into shape. In his influential work, De animalibus, written around 1260, Magnus states that such ideas began with poets and were untrue.21

In another bestiary, in contrast to the lion, whose courage is in its breast and whose strength is in its head, the bear’s head is weak and its strength is in its arms and legs. Allegorically, ‘the bear signifies the devil, ravager of the flocks of our Lord .. .’.22 Many bestiaries could not refrain from dwelling upon the lustiness of bears, especially where this pertained to human females. It proved difficult to suppress old pagan ideas of bears abducting young maidens for carnal purposes. In Scandinavia, for example, such stories continued to circulate. Although Olaus Magnus, in 1555, recounted the use of bears because of their strength as draught animals to pull ploughs or turn tread wheels to lift water, he could not resist informing his readers about the young woman who, abducted by a bear and made pregnant by the beast, gave birth to a baby with bear characteristics.23

In 1607, when Edward Topsell, a University of Cambridge scholar and cleric, compiled his History of Four-Footed Beasts (mostly a translation of parts of the five-volume Historia Animalium by the famed Swiss naturalist, Konrad Gesner), he catalogued everything then known about bears. He pointed out that they were ‘strong and full of courage’ and ‘can tear in pieces both oxen and horses’. He then related a story similar to that told by Magnus but this time situated in the mountains of Savoy. Bears were ‘of a most venerous and lustful disposition’ and one was known ‘to have carried a young maid into his den by violence, where in venerous manner he had the carnal use of her body’. To prevent her escape, every day when the bear left the cave, he rolled a huge stone before the cave door. The bears’ manner of copulation, according to Topsell, was similar to that of humans, whereby the female lay upon her back and the male mounted her, his stomach against hers. In Topsell’s time and even earlier, this seemed to be the most remarkable feature about bears and the one that most set them apart from other animals. Topsell even noted that bears copulate for a long time and if they are both fat, ‘they disjoin not themselves again till they are made lean’.24

Also according to Topsell, bears moved into dens after mating where, without eating, they grew fat only by sucking their front paws. To be able to sleep through the whole winter, bears were known to eat the herb arum, which enabled them to fall into a deep sleep. Bears were subject to blindness and so they raided bees’ nests, where the stings caused them to regain their sight. Topsell cautioned that bears were not easily trained and should not be trusted. Bears, he said, will bury their dead, and reports from many countries claimed ‘that children have been nursed by bears’. Bears could also provide aid to those ill or in pain. If a woman in childbirth was having a difficult time one needed only to send a stone or arrow that had killed a bear over the roof of the house she was in to alleviate her symptoms. Furthermore, cripples were relieved of inflammation if the livers of a pig, lamb and bear were dried, mixed together, pounded into a powder and placed in the cripple’s shoes. Topsell also noted that certain bear parts were useful to prevent palsy and ‘women may go full time’ if they made ‘amulets of bears’ nails and wear them all the time they are with child’.25 These were representations of bears that issued not from empirical observation but from what we now see as the medieval imagination. Although Topsell was writing at the dawn of the early modern period when many other writers of bestiaries were becoming increasingly interested in natural history as a science, Topsell still wrote in the earlier tradition of religious allegories.

He was by no means alone in his beliefs, however. Many people at this time still related old stories and harboured ancient fears. Dragons lay beyond the city walls, deep in dark mountain caves. Certainly the monsters and dragons that peered down from pillars on church congregations throughout Europe reinforced this fear. Even as late as 1672, when cave bear skulls larger than those of contemporary bears were found in caves in Hungary, the skulls were often attributed to dragons. Large deposits of cave bear bones – then believed to be dragon bones – discovered in caves in medieval times found their way to apothecaries’ shops, where they were ground up for medicines or marketed as unicorn horns.26

A Flemish tapestry of the early 15th century showing the pageantry of a bear hunt. |

By the Christian era, according to Barry Sanders, bears disappeared as a ‘subject for visual arts . . . bears no longer inspired the visual or plastic arts to any extent.’27 The bear began retreating along with the woods that had previously covered much of Europe. Yet occasionally they inhabited paintings and tapestries where they were generally the subject of an elaborate hunt.

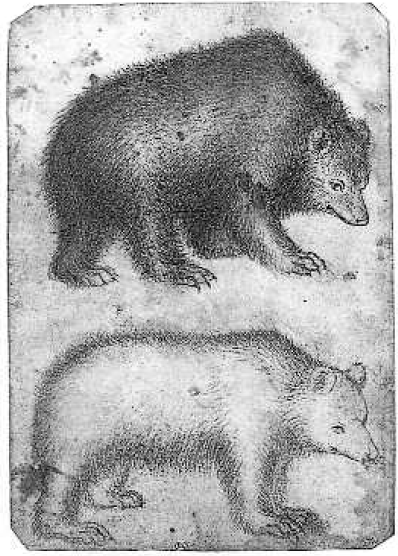

Pisanello’s studies in chalks (1430s) are rare realistic depictions of the bear for the time, being neither allegories nor hunting imagery.

Painting, one of the best media to reflect changing customs, suggests that hunting bears with packs of dogs began in the seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century, paintings depicted bears in desolate wilderness settings beset by dogs and mounted hunters with spears. In The Naturalists Library XV (1840), Sir William Jardine lamented that great hunts with packs of dogs were no longer held in Germany and Poland:

Formerly . . . a bear hunt was reckoned among the most princely of sports. Hunters on horseback, armed with spears, others on foot, with special weapons, packs of hounds, sustained by numerous couples of bear dogs and mastiffs, and whole troops of country people, some bringing nets of great length, others implements to make fires, and all furnished with horns, trumpets, drums and other kinds of noisy instruments, assembled to drive the game together, and destroy it by open force.28

The use of specially trained dogs to hunt bears continues to the present day in many parts of the world.

In America, as in Europe, bears were creatures to be disposed of as quickly as possible. Fur trappers would sometimes trap bears, but there was little profit to be had from their pelts. Professional hunters with dogs, however, were hired by ranchers to kill bears along with wolves and cougars that preyed on sheep and cattle. One of these professionals, Ben Lilly, who hunted bears in the East Texas hill country before moving to New Mexico to hunt the length of the New Mexico–Arizona border, acquired a great reputation for exterminating bears. Indeed, so efficient were professional hunters that today few bears can be found in the west outside Yellowstone National Park and the Greater Yellowstone System that surrounds it.

A German princeling hunting American grizzlies in the 1830s, in a lithograph by Karl Bodmer. |

A 19th-century bear hunt, from Outing magazine.

A Family of Bears in a Forest, by J. M. Roos, shows bears realistically, with no hint of the fears they had earlier inspired. |

Hunts were less of a team effort in the Orient, ifpaintings are to be believed. Nineteenth-century Japanese paintings show single warriors attacking bears with swords. Here the emphasis is on the skill and bravery of the warrior rather than, as in European paintings, on the extermination of the bear and, by extension, the wilderness.

By the nineteenth century, fears of bears and dragons had long receded. Bears in the wild had disappeared entirely from much of Europe, remaining only as sources of entertainment or in the form of carved replicas used as fetishes, or as adornments. Carvings that might once have been fetishes or that served some religious function in Scandinavia, were duplicated in jewellery. New kinds of bear paintings emerged less as art than as anthropomorphized cartoons.

An example of modern Finnish jewellery that draws on ancient Finnish designs for fetishes and protective charms. |

In the United States, Thomas Nast used animals as political cartoon figures in the pages of Harper’s Weekly between 1860 and 1880, but the first to use bears in such a way seems to have been William Holbrook Beard, a painter and member of the National Academy of Design. From the 1860s on, Beard painted a series of pictures of bears mocking human foibles, including ‘The Bear and the Foxes’, ‘Bears on a Bender’, ‘The Bear’s Picnic’ and – most famous of all – ‘The Bear Dance’. Although considered vulgar by some and satirical by others, they were immensely popular with the public. Beard particularly liked to paint bears in anthropomorphic settings because he thought they ‘have a smile that is vaguely a human expression, and is a real indication of humor or fun; they are great jokers’.29 During the last half of the nineteenth century, the animal cartoon genre grew increasingly popular in America, especially in politics.

The Russian Bear and the British Lion at odds over Central Asia, in a 19th-century political cartoon. |

The Bear Dance by William Beard shows how thoroughly bears were domesticated in the popular imagination by the 1870s.

If, by the nineteenth century, bears had become a subject of the visual arts, they were also a significant item for natural historians. Beginning around the end of the twelfth century, there was an explosion of interest in natural history led by such luminaries as Albertus Magnus and Roger Bacon. With the discovery of ‘new worlds’ in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, previously unknown animals and plants were shipped back to Europe, sparking scientific debates over classification and theological controversies that threatened to subvert biblical truth. In the course of the eighteenth century the scientific nomenclature for animals and plants invented by the Swedish physician and naturalist Carolus Linnaeus (Carl von Linné, 1707–1778) was gradually established, the same era in which nation-states were outfitting worldwide voyages of scientific discovery. Throughout this century and the next, museums and scientific societies were founded to promote the work of natural historians, many of whom maintained worldwide networks of correspondents who sent in data from far-flung regions.

|

An early drawing of a bear, reproduced in Thomas Pennant’s British Zoology (1761). |

First among the British natural historians before Darwin were Thomas Pennant (1726–98), Sir William Jardine (1800–74) and Thomas Bewick (1753–1828). Sprinkled through the pages of their natural histories were illustrations of bears, not only from Europe but other parts of the world as well. Descriptions of their habits, sizes and weights were included, often gathered from older works and from their correspondents’ accounts, resulting in a mix of wonderful truths and falsehoods.

The brown bear as seen in the 18th century, from the Comte de Buffon’s Histoire naturelle 1759–67).

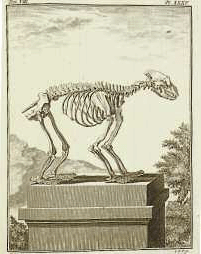

A bear skeleton, again from de Buffon’s Histoire naturelle.

With the rise of paleontology in Europe, many were led to the study of prehistoric bears, especially the cave bear. Georges Cuvier’s Recherches sur les ossements fossiles appeared in France in 1812, while in 1858 the Finnish schoolteacher and amateur paleontologist Alexander von Nordmann published his Palaeoazntologie Suedrusslands, I Ursus spelaeus (odessanus). In 1833 P.-C. Schmerling brought out Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles découverts dans les cavernes de la province de Liège. Others followed. In more recent times, Björn Kurtén, one of the most prolific students of cave bears, wrote numerous books and articles, including The Cave Bear Story (1976), Pleistocene Mammals of Europe (1968), The Age of Mammals (1971) and The Ice Age (1972), all of which included discussions of prehistoric bears. In 1961 Kurtén’s colleagues, F. E. Koby and H. Schaefer, published Der Höhlenbär.

In nineteenth-century America, as research on wild animals increased, the study of bears lagged behind. Sportsmen, who, in some cases, wrote quite scientifically, were more interested in deer, elk and moose than they were in bears. And most naturalists hesitated to confront C. Hart Merriam, the leading bear authority of the time. They felt intimidated by Merriam, who, in his exalted position as head of the Bureau of Biological Survey, had the resources of the government at his disposal as well as the status his position afforded. Unfortunately much of Merriam’s research turned out to be wrong. A taxonomist, Merriam repeatedly divided the single family Ursus arctos into separate species.30

Eventually, Merriam’s theory collapsed, giving others a chance to move into bear research. The naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton wrote several works on the grizzly, including The Biography of a Grizzly (1899) and Monarch, the Big Bear of Tallac (1904). William Wright wrote The Grizzly Bear (1909) and Ben, the Black Bear (1909). A decade later Enos Mills penned The Grizzly. Another well-known writer about bears was Theodore Roosevelt, twenty-sixth president of the United States and founding member of the elite organization for hunters, The Boone and Crockett Club, established in 1888. Between 1885 and 1909 Roosevelt published several pieces on bears. He worked in the older tradition, gathering stories from hunters and explorers and conflating them with his own observations as a bear hunter. His writings came to assume the status of ‘scientific’ truth. Roosevelt began one essay on bear behaviour with the words, ‘My own experience with bears tends to make me lay special emphasis upon their variation in temper.’31 He also called for more complete studies of the bears of Yellowstone: ‘It is earnestly to be wished that some Boone and Crockett member... would devote a month or two, or indeed a whole season, to the serious study of the life history of these bears.’32

Bears near a hotel in the Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, c. 1920s. |

John and Frank Craighead have done more than Roosevelt could have hoped. They have spent years studying the grizzly bears of Yellowstone and produced articles, research papers and books, making them today’s leading authority on the subject. The Craigheads are not alone. Since 1900, perhaps earlier, a growing interest evolved in North America in the preservation of its wilderness and of the plants and animals that constituted much of it. Along with many other animals, bears increasingly became a subject for serious research.

Charles T. Feazel’s study of the polar bear, White Bear: Encounters with the Master of the Arctic Ice, is the result of years of scientific work in the Arctic. Despite his first-hand accounts of polar bears, Feazel remains wary of them and sees them as the rulers of the Arctic. Kennan Ward’s account of grizzlies, Grizzlies in the Wild, is less scientific than Feazel’s study, but details his observations of bears in one of America’s last great wildernesses.

Although there are several studies of pandas, such as the excellent Men and Pandas by Ramona and Desmond Morris, George B. Schaller’s account, The Last Panda, is perhaps the best. Schaller, one of the world’s most respected naturalists, based his study on a multiple-year panda project initiated by the Chinese government and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and funded in part by the New York Zoological Society. The goals were to investigate panda adaptation to a diet of bamboo, study panda movements, and define conservation methods. The Last Panda is also the story of research overseen by two bureaucracies with differing agendas; the Chinese government and the WWF.

Sy Montgomery’s Search for the Golden Moon Bear is a tale of science and adventure. Montgomery and Gary J. Galbreath travelled throughout southeast Asia to look for this rare creature and to identify cultural practices of bear torture and exploitation in the region. Another scientific but more horrific account, specially researched for the WWF/TRAFFIC, was The Asian Trade in Bears and Bear Parts by Judy Mills and Christopher Servheen. Mills has written extensively on the exploitation of bears. Servheen is interested in the international conservation of bears, especially Asian bears and grizzlies.

Findings of bear research remain controversial. The question of the existence of cave bear cults still sparks debates among paleontologists, archaeologists and art historians. Another controversy centres on whether the panda is a bear or a member of the raccoon family, although most scientists now favour the former interpretation.

In the area of behaviour studies, bears still pose problems. Are bears prone to attack humans or are they apt to flee? The rehabilitator Benjamin Kilham, whose Among the Bears: Raising Orphan Cubs in the Wild, is one of the best works published on black bear behaviour, believes they are scared of humans and, given the opportunity, prefer to flee rather than attack. Others agree, including Lynn L. Rogers and Jack Becklund, author of Summers with Bears. Yet some scientists disagree and fear that those who rely on Kilham when they encounter a bear may discover that the bear has not read his book. Even if Kilham is correct in his observations of black bears, does his thesis hold for other species of bear, such as the polar bear or the grizzly?

Bears pose fascinating questions for science and medicine and their answers could benefit human health. Bears in the northern hemisphere become exceedingly obese before denning, with fat making up much of their weight. Yet the health of hibernating bears is not affected by this fat accumulation. As M. A. Ramsay notes in his article, ‘Cycles of Feasting and Fasting’, bears ‘display some of the most extreme examples of seasonal fatness known amongst mammals and clearly have evolved means of remaining physically fit while obese’. Research seems to indicate that where this fat is stored is more important than the amount stored.33

In winter, polar bears add four inches of fat to their hindquarters and lesser amounts elsewhere on their bodies. But this is not the only means by which polar bears keep warm. Scientists are learning much about solar energy from research on these bears, who can often overheat in temperatures way below freezing. What they have found is that the bear’s fur ‘pulls warmth from one of the coldest places on earth and pipes it more efficiently than steam heat to a skin capable of absorbing it... Polar bear skin is, in fact, one of nature’s most efficient uv absorbers. Ultraviolet light penetrates clouds, so Nanook’s efficient solar collection system works even on overcast days.’34

Why after such long periods of inactivity in the den is there no loss of calcium in bears’ bones? Why do the bones not become brittle as they do in humans during hospital stays or space flights? It seems bears have the ability to recycle calcium back into calcium bone deposits. Other questions related to hibernation and physical processes remain. How is muscle tone preserved over months of hibernation? Since bears do not eat, drink, urinate or defecate in these periods, how do they avoid ureic poisoning from cellular breakdown which generates the production of urea? Humans recycle about one quarter of the urea they produce back into proteins and the rest is eliminated. Bears apparently recycle all the urea they produce during hibernation. How they do this is still unknown, but the answer might help people afflicted with kidney failure.35

Another scientific mystery is the bear’s directional ability. After removal from a site, how do bears return unerringly and in almost a straight line to their home ground? As Lynn L. Rogers, a wildlife research biologist with the us Forestry Service, notes, they move ‘as if on directional autopilot with little regard for terrain or obstacles’.36 They almost always travel by night, even on nights that are cloudy or moonless, or during snow storms. Are they guided by scent? Bears have the most highly developed sense of smell of any mammal in North America. Do they possess magnetite – a substance found in the brains of homing pigeons and some other mammals – that acts like a compass? Do they make and store mental maps of areas beyond their home territory? Whatever the process, bears possess a phenomenal navigational system. ‘Nuisance’ bears removed from national parks, suburbs and farming-ranching areas often find their way back. Often, the return journey is fraught with danger; many bears are killed by cars when they attempt to cross highways at night. Even if the bear does return safely, it stands a better chance of being shot rather than of being caught and taken away again. For some reason, there seems to be more success in removing young bears than older ones.37

The impact of modern civilization on bears and their habitats is a serious concern for many interested in bear welfare. In some places suburbs are encroaching upon bear habitats, forcing them into areas where survival is more difficult. Some bears, drawn towards populated areas by garbage, are either shot or removed. The only access most people have to bears is by visiting zoos or national parks. The latter provide the best opportunity for the public to see bears in a natural habitat, but as more people crowd into the parks the bears recede deeper into the interior to avoid human disturbance. Unfortunately, so little is known about bears or their behaviour by people who like to hike, bike and camp in bear country – national parks or wilderness areas – that every year there are confrontations between humans and bears, often resulting in injury or death.

This is especially true in the Arctic, where such confrontations are increasing at a rapid rate. The Inuit, who have shared their world with polar bears for thousands of years, understand and respect Nanook. Many have even claimed to have learned hunting techniques from watching bears. Nonetheless, they observe philosophically that when they hunt the great white bear, sometimes they win and sometimes the bear does. Long years of observation have taught them much about Nanook’s behaviour, leading them to disagree at times with scientists who may only observe bears for short periods.

A polar bear looking in through the window of a car, Churchill, Manitoba, Canada, 1997. |

The polar bear is still the monarch of the realm of ice and snow. This is what the Inuit know and tourists and oil company workers still have to learn. The polar bear is the only bear that stalks humans. On dark nights in blowing snow or even in the dusk that passes for daylight in the Arctic winter, the white bear is a silent killer – something its victims often learn too late. Despite guards with rifles (who are sometimes called ‘bear bait’ in jest), hired by oil companies to watch for bears around Arctic oil rigs and to protect scientists studying ice formation and ocean currents, bears still kill or maim those who make mistakes or are ignorant of Nanook’s behaviour.

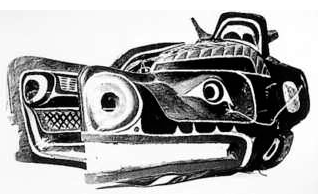

The Kwakwaka’-wakw transformation bear mask of the Kwakiutl Indians of British Columbia, Canada. Mask closed. |

The same bear transformation mask, open to show the human within.

This is also true for tourists seeking a bear experience’ who ignore posted signs and safety tips in order to get that special photograph. In Churchill, Manitoba, on Hudson Bay where many of Canada’s polar bears congregate each summer waiting for the pack ice to start reforming, several businesses cater to tourists seeking to observe bears. Too often, to their misfortune, tourists fail to realize how fast polar bears can run, how high they can reach standing on their hind legs, and how strong they are.

For thousands of years, bears and humans have shared the northern hemisphere. In that time bears have mastered several environments, polar ice fields, mountains and plains in North America, Asia and Europe, and the rainforests of southeast Asia and South America. But because of the exponential growth of human populations worldwide, these environments are being rapidly extinguished along with the bears that live in them. Many organizations and governments are now seeking to prevent the further loss of bears, not least because they are realizing that bears are inexplicably linked to humans and to the human imagination. Or, as some Indian peoples believe – for example, the Kwakiutl of British Columbia – bears and humans are one.