6 Road to Extinction?

It is sad to think that toy stuffed bears outnumber real bears. As toy bears multiply, they fill the comfort needs of a growing human population that is inexorably forcing bears into extinction. The human demographic increase is destroying bear habitats, resulting in fragmentation of bear populations and in a decrease in bear numbers. Today, six, perhaps seven, of the eight species of bears are declining both in numbers and in range.

The brown bear roamed throughout Europe until about the sixteenth century. Until the ‘agricultural age’, bears and humans, despite sharing an ecological niche, had managed to coexist. But once the human population increased and shepherds and farmers replaced hunters, this niche became overcrowded, setting bears and humans on a collision course. Now bears exist in small, fragmented populations in only the remotest parts of Europe and are likely to disappear altogether if a management plan for their survival is not soon implemented.

Habitat destruction is most severe in the rainforest areas of South America and Southeast Asia, and in parts of the Arctic. Rainforest loss is only partly due to large lumber corporations that build roads into the forest to clear cut trees. Such activity allows the landless poor to move in and collect wood for fuel or practise slash and burn methods to carve out farms from the remaining forests. Mining companies, large farming concerns and ranchers are also responsible for habitat loss in South America and Asia. In many areas where vast rainforests once proliferated, only desert-like conditions exist today.

Bears still roam 1889 Morning in a Pine Forest, by Ivan Shishkin.

The loss of rainforest in South America is critical to the spectacled bear population, while in Asia the sun bear, the sloth bear, the Asian black bear and the giant panda are all affected by diminishing home territories. Giant pandas, one of the most endangered bears, are well-publicized victims of habitat loss. They used to range throughout central and southeast China all the way to Vietnam, but today they are fragmented into 20 small reserves, and it is feared that they may soon become extinct. China, in an effort to avoid this catastrophe, recently opened the vast Caopo Nature Reserve, adjacent to the Wolong Nature Reserve. It is hoped that with this larger reserve, and with Wolong’s successful breeding facility, pandas will move back from the brink.

Because of its popularity, the giant panda’s plight receives extensive coverage from the press. This helps to obscure the fact that pandas may actually be less endangered today than the small sun bear and the sloth bear. According to scientists, the sun bear is now very difficult to find in the wild and appears to have disappeared completely from many of its old haunts. Malaysia’s rainforests provide primary habitat for the sun bear, and the country is being deforested at a rapid rate. The sloth bear has also disappeared from many of its old territories. In the unrelenting competition for land between bears and indigenous human populations, the latter always win.

Habitat loss is not just a tragedy for tropical bears and pandas, but for the grizzly (brown) bear in North America. Hunting, trapping, poaching, road construction, poisoning, and the conversion of bear habitats to farmland and ranches have forced grizzly bears to take refuge in small pockets of remaining wilderness in the northern Rockies, primarily in Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks. Between 800 and 1,000 grizzlies exist in the United States, excluding Alaska. They, too, are now fragmented and separated from a larger Canadian population. A recent effort to open a corridor from Canada’s Yukon territory to Yellowstone to encourage freer movement of grizzlies into parts of their old home ranges in Idaho, Wyoming and Montana, was blocked by the George W. Bush administration after appeals from local ranchers and farmers who feared bears would endanger their cattle and sheep. Environmentalists, however, see this corridor as vital to expanding the genetic diversity of the isolated bear populations in this area of the United States.1 Unfortunately, bears do not have votes. Even in Canada, with the largest brown bear population in North America, some scientists estimate that 60 per cent are now at risk.

|

A Finnish bear, in what wilderness yet remains. |

Bears’ low reproductive rate is another factor posing a problem for maintaining grizzly populations. In Alaska, where there are estimated to be anywhere from 12,000 to 13,000 grizzlies – the highest number in the United States – the interval between litters of cubs is three to five years. Biologists interested in bear preservation note that this interval, combined with small litter sizes of one to two cubs, is a critical factor in their attempts to maintain viable populations, especially in the Greater Yellowstone region. In Yellowstone, where the grizzly population is about 200, of which it is estimated only about 40 are breeding females or sows, ‘scientists have calculated that the annual loss of only one or two mature females capable of reproduction may mean the difference between maintaining a stable population and eventual extirpation.’2 There is even fear for the future of Alaska’s grizzlies. Since World War II, the number of humans in Alaska has catapulted from 70,000 to 500,000 and keeps on growing. Human population centres with their widespread garbage dumps act like magnets for bears. Bears that are not shot for venturing too close to residential areas are often poisoned by eating cans, car batteries, engine oil and other toxic substances.3

The Arctic is another area where habitat loss poses a serious problem for bears. According to scientists, oil drilling on Alaska’s north coast disturbs the denning areas of female polar bears. The bears, extremely sensitive to the noise of drilling, often abort their cubs. Since the polar bear population also grows slowly, scientists fear increased drilling will have a disastrous effect on the region’s population. Another problem also threatens the bears. A warming of the Arctic caused by climate change (global warming), is melting ice shelves that polar bears use to hunt seals, their primary food source. Because the ice is melting earlier each spring and reforming later each fall, it is forcing bears to come ashore much earlier and depart later. Whereas summer is the time that bears south of the Arctic feed heavily in preparation for winter hibernation, for polar bears it is a period of near fasting. Bears now have to start their fasts earlier and continue them much longer. Hence, polar bears are weaker than in the past by the time winter sets in and they can start their winter hunts. This is critical for pregnant bears since they may not have accumulated enough fat to survive the cub-bearing season. Cubs born under such conditions have less chance of survival since their mothers produce less milk and what milk there is, is less nourishing.4

Poaching is still another major problem. The polar bear population is presently listed as being between 22,000 and 27,000. Many of them live in the Siberian Arctic. The closure of military bases and Arctic research stations has led to a rise in poverty in the region and a major increase in bear poaching. Poaching estimates range from less than 100 to as many as 1,000 per annum, but even at the lower figure it will be hard to sustain the Siberian polar bear population.

A polar bear being captured in Greenland. |

Toxic wastes are also threatening polar bears. Although these bears dine almost exclusively on seals, they seldom eat the whole animal, preferring to eat only the skin and the layers of blubber beneath. But toxic wastes accumulate in these fat tissues, so through eating the blubber, they become walking toxic waste dumps. Scientists have recently found hermaphrodite polar bears – bears with the organs of both sexes – in the waters above Norway, which they attribute to an accumulation of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBS) or other chemicals that disrupt normal hormone functioning in the tissues. Here, in a part of the ocean that is far from industrial sources of pollution, the residue of such chemicals as PCBS and DDT is a potent 90 parts per million in bears, and scientists believe this is to be a primary cause of the bears’ low birth rate.5 For some time it was suspected that the deformities were caused by PCBS and other industrial pollutants that mimic the hormone oestrogen, but there was no firm proof.6 But the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program, based in Norway, has confirmed that polar bears, along with seals and other arctic mammals, are showing significant contamination from several industrial toxins including PCBS and mercury. These chemicals are carried by fish and other marine life as well as by winds and ocean currents. More research is needed on what effects these toxic chemicals will have on bear reproduction.7

Foreign species or exotics introduced into their natural habitats, along with pollution, are also serious problems for maintaining healthy bear populations. In North America grizzly bears are now pretty well confined to Alaska and the northern Rocky Mountains in the United States, to the mountains of western Canada, and to Mexico. In the fall many grizzlies move to higher elevations to feast on meaty pine nuts produced in great abundance by the whitebark pine. Unfortunately, this pine species is being killed off by a fungus from Eurasia called blister rust. Beginning in 1905, this fungal disease became endemic in the eastern white pine forests of North America when it was introduced by seedlings brought over from Europe. In time, blister rust spread both westward and upward to the high elevation forests of whitebark pines. This is depriving grizzlies of a major dietary supplement.8 According to Kerry Gunther, a bear management specialist in Yellowstone National Park, with the demise of the whitebark pine, birth rates for grizzlies are likely to fall and death rates to rise.9 An added problem is the loss of the ‘refuge effect’, that is, the loss of pine nuts means that bears will no longer be drawn to higher altitudes away from the dangers of close proximity to human populations, especially hunters during hunting season.

Grizzly bears in the northern Rockies have five main sources of food: animals, mainly winter kill; whitebark pine nuts and other vegetation; spawning cutthroat trout and army cutworm moths. Cutthroat trout have also been increasingly in danger because non-native lake trout are illegally introduced into Yellowstone’s lakes by sport fishermen. Lake trout are fierce predators and ichthyologists predict that the cutthroat trout population could be cut by 70 per cent in the near future.10

Another concern is the effect of brucellosis on the Yellowstone bear population. The spread of this disease among the Park’s bison and elk populations worries surrounding cattle ranchers, who are fearful that the disease may spread to their cattle, so plans are being discussed to cull at least some of the elk. This would further reduce bears’ nutrients since these ungulates – especially the calves – constitute an important part of their diet. This could induce Yellowstone bears to forage outside the park boundaries in search of food, putting them at greater risk with local human populations.

But it is the army cutworm moths that present perhaps the greatest problem. Grizzlies feed heavily on these moths for three to four months of the year. It is estimated that one bear can eat from 20,000 to 40,000 moths a day and, because they are a rich source of nutrients, obtain as many as 30,000 calories a day! Unfortunately, changing land use in the Great Plains together with climate change may have an adverse affect on army cutworm moth populations. The moths ingest large quantities of pesticides and since bears eat the moths in such great numbers, the pesticides or toxins accumulate in the bears’ tissues at a rapid rate, as with polar bears eating seal blubber, causing sickness, genetic abnormalities and even death.11

Preserving and protecting the grizzly bear population in Yellowstone is difficult and complex. This can be seen in the evolution of management policy. In the early years of the park, to entertain the guests, bears were fed every evening. As early as 1891, park officials complained that bears were becoming a nuisance as they searched around the lodges for garbage. By 1910, bears standing alongside park roads were panhandling food from tourists. In 1916 Yellowstone recorded the first human death from a bear attack. Between 1931 and 1969, Yellowstone bears inflicted an average of 48 injuries on humans each year. Partly in an effort to counteract this problem, park officials devised a bear management programme in 1970. One of the restrictions called for the immediate removal of all garbage dumps. This ignited a long-simmering dispute between the park manager and noted biologists, John and Frank Craighead. The Craigheads, two of the world’s leading specialists on grizzlies, urged a gradual removal of the dumps. They predicted that without the dumps, bear–human conflicts would increase both in the park and beyond its borders, resulting in the deaths of many grizzlies.

Just as they feared, in the first two years following the closure of the dumps, 88 grizzlies were killed in or near the park, more than in Yellowstone’s entire history. So many were killed that by 1975 grizzlies in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem were listed as a threatened species. This initiated the Bear Recovery Plan, which many believed would be expensive to run and difficult to assess. They were right. In 1983 the Inter-Agency Grizzly Bear Committee was established to coordinate efforts to rescue the region’s bear population. Although the bears today show some signs of recovering from the massive slaughter of the 1970s, it is too early to tell if present policies will achieve complete success. Hampered by a lack of genetic diversity and prevented by surrounding human encroachment from ranging freely and mixing with Canadian bears, the Yellowstone area’s grizzly population remains weak and threatened.

Similar ecological problems are impacting bears in other areas of the world. The worldwide spread of industrial pollutants into rivers and oceans, especially PCBS and mercury, has resulted in dangerously high concentrations in salmon, seals and many other maritime creatures. Coastal brown bears that rely heavily on spawning salmon and who – like polar bears – often ignore the meat, eating primarily the skin, fat and roe, end up ingesting the very tissues in which these chemicals are stored.

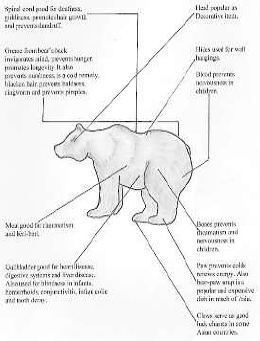

A recent study on the Asian trade in bears and bear parts carried out by Judy Mills and Christopher Servheen under the auspices of the WWF, asserts that the trade in bear parts is a threat to bears’ survival equal to or greater than the loss of habitat.12 The most sought after parts are gall bladders. These form part of traditional Chinese medicine and, gram for gram, fetch as much on the black market as heroin. In 1991 they fetched eighteen times the price of equivalent weights of gold. Other bear parts are also extremely profitable. In the same year, 1991, it was estimated that the market value of an adult bear, including its gall bladder, paws, hide, claws, bones and meat, was about $10,000.

It is difficult to estimate the number of bears killed in Asia for their body parts, but if the numbers of gall bladders are any indication, it must be in the thousands. In the markets of many cities in China and southeast Asia, dried gall bladders are displayed for sale in stall after stall. Even in Singapore, where there is a law against selling bear parts, they can easily be found in the marketplace. Of course, not all the gall bladders come from Asian bears. An international smuggling trade in bear parts includes Canada, the United States, eastern Europe and South America. Nor does the number of bears killed for their body parts reflect the extent of the trade and the actual drop in bear numbers in the wilderness. Many adult bears are killed in order to capture cubs, which are then sold in Asia as pets or to bear ‘farms’, where tubes are inserted into their gall bladders, generally without the use of anaesthetics and they are, in an agonizing process, constantly ‘milked’ of their bile.

Bear body-parts used for traditional medicine. |

A selection of products at a bear-bile farm in China, 2000. |

A bear-bile farm in China, 2000.

In 1991, there were 30 major bear farms in China holding more than 100 bears, as well as many smaller farms. Currently China plans farms capable of holding 40,000 bile-producing bears. Bear farms in North Korea, where the practice began, have been operating for over 30 years. Several other Asian nations are eager to start up farms of their own. Because of the growing scarcity of bears in the wild, especially black bears that are reputed to give the highest quality bile, Chinese officials see the milking of bears as a ‘conservation’ measure; a better solution than killing wild bears for their gall bladders. It would be of little comfort to the bears that spend much of their lives in pain, enduring pus-filled abscesses and confined in cages too small to turn around in, to know that they are suffering for the sake of their wild brethren. Though ‘bear bile’ can now be produced artificially in laboratories and is sold in pill form, many Asians reject both the pills and the ‘milked bile’, claiming these are less efficacious than the bile of wild bears.13

|

A cage close up at a bear-bile farm. |

The ‘conservation’ rationale for bear farms is not nearly as meritorious as Chinese officials want people to believe. The farms pose a setback for bear conservation efforts in China. Instead of conservationists working to learn more about bear ecology in order to protect bears and their habitats, they are devoting their efforts to developing more effective breeding programmes for captive bears and seeking ways to increase bile production. Very little is known about Asian bear ecology, and without such knowledge it becomes even harder to assure the survival of wild bears.

Bear farms are also an excellent way to move illegally acquired bears and bear parts into the market. Under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species or Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), there are many loopholes that facilitate the bear trade. Since it is difficult to distinguish between parts from captive-bred bears or bear parts and those acquired in the wild, the illegal trade flourishes. It is easy to produce false documentation, and because minimal records are kept anyway, it is a simple matter to circumvent the system. In turn, the ease with which bears and their parts are moved in and out of bear farms encourages poaching and illegal trading.

The same is true of bear parks in Japan where, according to Mills and Servheen, a secret international trade in bear parts flourishes. As of 1991, there were eight bear parks in Japan with one more under construction and another proposed. Altogether, they house around 1,000 bears, including all bear species except pandas. In most the bears’ living conditions are deplorable. They live out miserable lives crowded together and surrounded by concrete. In one park, adult bears averaged only 1,551 square ft (13 m2) of space during the day and 614 square ft (1.3 m2) at night. They are fed on restaurant scraps and have been known to die after swallowing sticks used to skewer chickens for cooking. There is a good deal of fighting among the males, and many die with their wounds left unattended while others just drop dead. The most aggressive bears are placed in isolation and starved until they lose the energy to fight.14

These parks also promote the selling of bear parts to tourists. According to Mills and Servheen, one park sold bear meat in small souvenir cans and bear skins with the paws and head attached. In one park in 1991, canned meat sales brought in about $3,000 while bear rugs fetched $3,000 each. One bear park allows preferred Korean and Japanese customers to select a bear from which the gall bladder is to be taken. The chosen animal is then isolated and starved because it is believed that starving makes the gall bladder grow larger. When the bear is ‘ready’, an air-driven hammer is used to stun it, and killing is completed by cutting its throat.15

Tourists enjoy the bear parks for the entertainment they provide. They can watch bears participating in circus-like acts or fighting over food scraps. Some parks provide visitors with plastic guns that shoot food. A few have small learning centres that provide information on bears worldwide. Nonetheless, critics of bear parks see them as ‘agents’ that launder bear gall bladders and other parts for profit, stimulating the commercial trade in bears while failing to promote the conservation of wild bears.

Mills and Servheen believe the trade in bears and bear parts will escalate, and as bears disappear from Asia, those elsewhere will supply the trade.16 To some extent, this is already happening. Evidence from Canada and the United States includes bears found dead in national parks with their gall bladders and paws removed. The increasing levels of affluence in Asia, the opening of borders and escalating trade worldwide, paint a grim picture for the future of bears, especially when the profits to be made are so high (some Chinese and Korean bear parts poachers in Siberia, for example, dissemble as timber industry workers).

It will be hard to bring an end to this trade. Part of the problem is the difficulty in enforcing international regulations against trade in endangered species set forth under CITES. Those who attempt to do so are often powerless to prevent illegal trafficking in bear parts or the selling of bears to farms, parks or private individuals as pets because of the way bears are classified. CITES places them in three main categories under Appendices I to III, with Appendix I listing the most critically endangered species. This first group includes sun bears, Asiatic black bears, giant pandas, Tibetan brown bears, Himalayan brown bears and Mexican grizzlies. These bears are considered to be the most threatened by extinction and are therefore – supposedly – protected. Appendix II lists American and European brown bears (outside Russia), and polar bears. These bears, while not presently considered threatened with extinction, certainly may be in the near future if strict regulation against their trade is not enforced. Appendix III lists only the Canadian black bear. This third level enables countries to call on others for aid in helping to protect a species from extinction. Obviously, not all bears receive equal protection.

Added to what many consider to be major defects in the present CITES rankings for bear protection is the fact that not all countries are signatories. Although some Asian countries are party to CITES, many of their neighbours are not, facilitating the illegal smuggling and sale of bears. As of 1991, Bhutan, Myanmar (Burma), Cambodia, South Korea, Laos, Taiwan and Vietnam had not joined CITES. This means that bear traffickers who acquire bears or bear parts in a country that has joined CITES need only say that they acquired them in a non-CITES country to gain permission to sell the bears or their parts back in the CITES country. For example, bears illegally killed by poachers in Thailand can be smuggled into Cambodia and then brought back ‘legally’ into Thailand simply by claiming they were acquired in Cambodia. Under such conditions, and because it is so difficult to determine either the true provenance of bears or bear parts or their legal status, customs officials increasingly do not even try.

Some Asian countries have imposed their own regulations regarding the sale or exploitation of bears, but again it is easy to circumvent these laws simply by claiming that the bear or bear parts came from somewhere else. In Singapore, conservation officials point out that to prove a crime not only must the dealers in bear parts be caught in the act, but that even when people are caught, all they have to do is argue that the parts came from American black bears or Russian brown bears or were acquired before Singapore signed up to CITES. Since no documentation is required, it is difficult to prove otherwise. Some conservation officers point out that it is hard to distinguish bear gall bladders from pig gall bladders, making positive identification even more difficult. Even in the United States, laws vary among states regarding the sale of bear parts. The same applies to Canada and its provinces.17

Yet another problem in the enforcement of CITES is the frustratingly complex procedure necessary to make an arrest. Poachers who flaunt regulations and use loopholes are nearly impossible to stop. That being so, why is the trade not curtailed at the market end by arresting those who sell to the public? Wildlife dealers in Singapore say that government agents will never learn enough about the illicit trade to achieve anything effective ‘because everyone involved knows everyone else, and a law enforcement officer would be obvious to them’.18 Those who carry out the trade are well versed in the law and know how to get round the restrictions. In Cambodia, even though it is not a party to the CITES convention, there are laws regulating the trade in bears and bear parts but there are so many loopholes that it is easy to evade prosecution.

In Search for the Golden Moon Bear, Sy Montgomery illustrates the problem of enforcement. When she and an officer from the Wildlife Protection Office visited a stall in Cambodia filled with illegal bear parts, the woman who owned the stall smiled and nodded to the officer knowing he could not do anything. As the officer explained, the stall also served as her residence, bringing it under a different set of regulations. To search a residence, the officer claimed he had to obtain signatures from several other agencies and then collect a force of about ten agents. This would give plenty of warning, so that by the time the agents arrived to confiscate the illegal bear parts they would have ‘disappeared’. According to Montgomery’s source, some dealers would not hesitate to murder anyone who tries to interfere.

Interpol considers the trade in wildlife the second largest illegal trade in the world (second only to the drugs trade), and those who deal in wildlife also often deal in drugs, arms and people (including the slave trade and prostitution). The agents trying to stop the trade claim that poachers and traffickers in wildlife are as organized as the Mafia and pose as much danger. It is little wonder that agents often think twice before trying to enforce laws against poachers and sellers of bears and bear parts and that protecting bears under CITES is so difficult.19 Mills and Servheen report that when a Thai conservation officer caught wildlife traffickers poaching bear, she was warned ‘her health would be in danger if she did not back down’. They noted ‘corruption was widespread and well known’.20

In India and China, bear meat is used in traditional medicine, but in much of southeast Asia, China and Japan it is also served in culinary delicacies, including bear-paw soup. It even appeared on the menu at a prestigious Western hotel chain’s restaurant in Seoul, South Korea. Bear paws first became popular as a delicacy during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) in China. They are even mentioned by Topsell as being considered a tasty dish in England in the early seventeenth century.21 The appreciation of the dish spread through most of southeast Asia, and the cost of this culinary delight has contributed to the decimation of bear populations. Just one shipment of bear paws weighing 8,800 lb (4,000 kg) intercepted in 1990 in a Chinese port represented 1,000 bears killed by forestry officials working with Chinese and Japanese merchants. In Japan, it is legal to kill ‘nuisance’ bears. Since farmers can greatly supplement their incomes by selling them, any bear seen becomes a ‘nuisance’, often ending up on a plate in an upper-class restaurant.22

Although bear paw soup can be found on the menus of many Chinese restaurants throughout Asia, it miraculously vanishes when conservation officers come through the door. The dish is extremely expensive, and to ensure that it is fresh, or that the patron receives the left front paw – considered by tradition to be the tastiest because many believe it is the paw bears use to gather honey – orders have to be placed several days in advance. Some restaurants keep live bears on the premises to assure the paws’ freshness. As orders are received, the bears’ paws are cut off, starting with the front left, until the tortured animals are left to hobble around on four bloody stumps. To curtail their anguished cries, their vocal cords are cut. It is almost impossible to comprehend their suffering.23 But laws against such cruelty and the sale of bear body parts are hard to enforce when the majority of the population resists their enforcement. Thus the profits remain great while the risks of fining or imprisonment are small.

According to at least one report, people from several countries of southeast Asia visit Thailand on bear-eating tours. Although Thais refrain from eating bear meat, several restaurants owned by Koreans or Chinese serve it. Despite Thailand being a signatory of CITES, bears are frequently hunted for the trade. Mills and Servheen interviewed one person ‘who witnessed a hunter carrying a poached bear back to a camp inside Thailand’s Khao Yai National Park, where nearly 60 poacher camps existed at that time’.24 Traders in wildlife often enlist poor villagers living on the edges of national parks in Thailand to poach bears and other animals. If a dealer obtains an order for a particular animal, all he needs to do is alert these villagers, expediting the order and avoiding the delays that hunting for the animal on the black market would incur. ‘Entire villages on the fringes of national parks [in Thailand] survive on the poaching trade that feeds the wildlife restaurants of Asia.’25 In Taiwan, a similar situation exists. Mills and Servheen claim that three bears were killed for their gall bladders in the Lala Mountain Reserve, a sanctuary set up to protect them. The hunters claim that by ignoring the Wildlife Conservation Law in Taiwan, they can make about $2,700 for each bear killed.26 The dealers who purchase these bears make even more on their resale.

In 1991, a raid by the Thai Crime Suppression Division on a farm south of Bangkok found 4 freshly killed bears and some 40 people, mostly Koreans, feasting on the meat. They also found several live bears, more hidden in a nearby village, a refrigerator filled with 48 bear paws, and records of the sale of bear gall bladders and paws. The farm was advertised in Korea and Taiwan as a restaurant and outlet for traditional medicine. ‘Sixteen tour companies had been bringing in groups of tourists from South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong to eat protected [bear] species and buy medicine made from their parts.’ Several Chinese medicine shops were associated with the farm, which also provided bear meat for Korean restaurants in Bangkok. The bears were smuggled to the farm by boat from Cambodia and overland from Myanmar (Burma) and hidden in the surrounding region. The farm itself was kept under tight security and bears were killed only on order. ‘The farm’s owner, brother of Thailand’s deputy commerce minister, claimed the farm was a zoo set up for tourists and to help save endangered animals from extinction.’27

Several approaches have been suggested to try and counter the decline in bear populations worldwide. One suggestion is that bear eggs and sperm be frozen in a process known as cryogenics, and kept in freezers until conditions in the wild are more advantageous for bear survival. While this is probably possible, who will teach the cubs how to survive in their new environments? Mother bears do far more than just give birth to cubs. They ‘acculturate’ them to their surroundings over a period of about two years, teaching them to hunt and where and when to find plants and other food sources, in short, how to interact with and survive in their particular ecosystems.

Less radical suggestions include building special bear reserves or preserving them in zoos. Reserves can be effective in species’ preservation but they have their limits. Small reserves are more acceptable to surrounding human populations, but this demands the constant culling of the animals to keep their numbers down to a level their food supplies can healthily maintain. Larger reserves are superior but are less easy to defend against growing human populations that constantly cross the reserve’s borders seeking fuel, meat and cropland. Sometimes large reserves are built across the territories of two distinct bear subspecies, resulting in the extinction of both. Many feel that several reserves in a particular area should be connected to each other by corridors. Others think that corridors could help to spread disease, and ask whether bears would actually use them.

Zoological parks or gardens are valuable in the short term. Most of the larger zoos worldwide are careful not to allow interbreeding and scrupulously comply with stud book regulations. But the rising costs involved in keeping each animal poses a constant challenge to zoos, a challenge they are sometimes unable to meet. Besides the financial costs involved, zoos also find bears very difficult to keep, since these strong, intelligent and observant animals all too often manage to effect escapes, creating panic. Bears, especially polar bears, are prone to stereotyping, a term used to denote repetitive behaviour like pacing and head swinging, which incurs public criticisms of zoos. Although there are several levels of stereotyping, some of which are natural, the general public is not aware of this and zoos are often accused of maltreatment.

Some zoos have tried to capitalize on their conservation function by reporting their progress in introducing captive bred animals back into the wild. Reintroduction programmes, though, are not only very expensive to plan and carry out, but do not always work. It is easier to reintroduce herding animals to their former habitats than solitary animals like bears. Another problem in introducing bears back into the wild is that there is increasingly less wild left.28 In 2002, Seattle’s Woodland Park Zoo celebrated the birth of a sloth bear, an endangered species. The zoo participates in the Species Survival Plan and notes that although there are only 48 sloth bears in captivity their goal is eventually to have more than 60. They hope to be able to introduce the zoo-bred animals back into the wild. Unfortunately, as the zoo points out, the bears’ natural habitats in southeast Asia are rapidly disappearing while poachers eagerly await new arrivals. So will zoos’ bear reintroduction programmes merely serve to enrich poachers?

In many parts of South America, economic conditions closely resemble those existing in parts of Asia. Poor farmers barely eke out a subsistence living. Killing spectacled bears often gives them the means to survive. Besides its meat and skin, the bears furnish fat, organs, blood and bones. The fat is believed to provide relief from rheumatism, blindness, gall bladder attacks and muscular pain. The bones are ground up and given to children in the belief that they will ensure good health. Warm blood is drunk as a general tonic, while eating gall bladders is believed to prevent blindness and cataracts. Some gall bladders find their way to Asia, providing desperately needed cash for peasant farmers.29

In some places in South America, the spectacled bear is revered, in others reviled. Myths and legends tell of bears stealing young unmarried women and young boys. Where these stories prevail, bears are killed on sight. But there are other reasons for the spectacled bear’s decline. Bears are seen, with some truth, as cattle and sheep killers. Deforestation of much of the bears’ territory have driven many of them to seek refuge higher in the mountains, with fewer food resources, and may put their survival at risk. In some areas deforestation has fragmented bear territory, resulting in isolated populations of spectacled bears. Because they live much of their lives in trees and nest in trees at night, deforestation deprives them of a vital environment. This is also true for some bears of southeast Asia. Deforestation forces them to search for new forest areas, which may soon no longer exist.30

A 1936 poster for Brookfield Zoo in Illinois – a fanciful view of the bear. |

Spectacled bears’ habitats are also areas of political unrest, drug production and rebel warfare. Government-ordered aerial spraying of coca plantations as part of the war on drugs kills both vegetation and bears. Spectacled bears are also killed to provide food for rebel armies living in the rainforest.31

Bears are often captured and used for display at roadside hotels and restaurants to attract tourists or to be sold as pets. Whether tourist attraction or pet, the bears suffer. Their nutrition is poor; they live in crowded, squalid cages; are prone to disease and abuse and live out their lives in discomfort and pain. Bears kept under such conditions have been known to attack and sometimes kill children. This stirs up antipathy towards bears and encourages the hunting and killing of bears in those areas.32

Bear hunting has often been cited as a cause of bear depopulation. As we have seen, it certainly can be in Asia, South America, the Arctic, and in parts of North America, but it does not have to have this effect. Because hunting black bears is a major sport in West Virginia, a mountainous state in the eastern United States, the declining bear population became a cause for concern not only among conservationists but also among hunters. In seeking a solution, the state did not ban hunting but moved the hunting season one month later in the fall. Bear researchers noted that pregnant female bears and females with cubs were the first to begin hibernation in the fall. The second to go into dens were young males and the last the older males. By moving the hunting season females and young male bears were protected from hunters who then only had access to the older males. This led to a marked rise in the bear population. This remedy may be applied in other states where bear hunting is also a fall sport and bear populations have fallen.

Some problems associated with climate change have already been mentioned, but there are other, less apparent yet no less potentially injurious, effects of global warming on bears. As oceans warm, fish like salmon that require colder waters could migrate northward, depriving bears living along the coasts of Washington state and British Columbia of a major source of nutrition. With the one degree of warming experienced so far, bird and animal species are already moving and some plant and tree varieties are also being found further northwards or further up into the mountains. Might whitebark pines, whose pine nuts form a significant part of grizzly bears’ diets, move yet higher up mountain slopes until they run out of mountain? In many parts of the world, such northward migration of plants and animals is impossible because of the physical barriers imposed by humans and their infrastructures. Animals are perhaps less affected in this migration process since they can move faster than plants. Even so, they are restricted by fences, highways, dams, urban expansion, new housing developments, and slash and burn agriculture and logging.

Will the plants that bears depend on disappear? Will the spread of plant or insect-borne diseases caused by global warming affect bear populations? Will rising oceans created by ice melting in the Arctic and Antarctic regions flood coastal areas in southeast Asia where sun bears search nightly for insects?

While it is true that bears have survived other major periods of climate change and that they are more adaptable (because of their omnivorous feeding habits) than many other animals, bears have never had to start from such a weakened base and in a world of such enormous habitat loss, toxic waste and increasing human population. There is also evidence that in the past climate changes occurred far more gradually than is happening today. With most bear populations plummeting and many hanging on in isolated communities, survival under climate change conditions is problematical. Just as the cave bear became extinct, so might history repeat itself with one or more of the current bear species.

We do not know how quickly global warming will occur or what its full effects may be on bears; nor do we know whether certain bear populations will be more affected than others. Unfortunately, we probably will not know until it is too late. What we do know is that it is unlikely the present trend of global warming will stop: indeed, scientific computer projections inform us that it will continue through this century and beyond, but will the pace, although fast when compared to earlier periods of warming, be gradual enough for species to have time to adjust and survive? These are important questions for which we have no answers.

Christopher Servheen, who has studied bears all over the world, believes that bear protection efforts should be linked to other conservation programmes. He offers suggestions as to how this might be accomplished. Watershed protection to assure local water supplies could be linked with the protection of forests and sustainable forestry. The practice of sustainable forestry would provide economic incentives to local populations through lumbering and at the same time could stop the fragmentation of bear habitats and assure long-term survival for bear populations. Such programmes would help save bears but would also create jobs and raise standards of living for local populations.33

Of course, money is important to put such programmes into effect but it is also needed to educate local populations. Likewise, money is essential for research, dissemination of research findings, and for the enforcement of regulations. But regulations are useless without sufficient enforcement and fines high enough to inhibit poaching. It appears that neither local nor national governments in many places can do it all. Enforceable multinational agreements are required and international organizations like the United Nations, the WWF, TRAFFIC, and the World Society for the Protection of Animals are all vital to provide the required education and support for conservation.

The international CITES agreement of 1973 signalled a major attempt to control the trade in endangered species. While flaws in this agreement exist where bears are concerned, the flaws may be less in the agreement itself than in its enforcement and in the fact that several countries have so far chosen not to sign up. Other international agreements, although more limited in scope, have proved effective. Beginning in 1965, five countries with polar bear populations – Canada, the Soviet Union, Denmark, Norway and the United States – met in Fairbanks, Alaska, to discuss the protection of polar bears and to work out what steps were needed to be taken to study the bears and their habitats in order to construct a viable conservation plan. Scientists from all five countries developed a plan, the International Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears and their Habitat, which was signed at a conference in Oslo, Norway, in 1973. This requires each signatory nation to protect polar bears and their habitats.

Each Contracting Party shall take appropriate action to protect the ecosystems of which polar bears are a part with special attention to habitat components such as denning and feeding sites and migration patterns and shall manage polar bear populations in accordance with sound conservation practices based on the best scientific data.34

Although the agreement has no enforcement mechanism, the polar bear population has rebounded since the 1960s. The George W. Bush administration’s attempts to turn the Alaskan National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), a prime denning ground for polar bears, into an oil exploration area is now threatening the spirit of this agreement.

Another agreement modelled on the one above is the Inuvialuit–Inupiat Management Agreement on Polar Bears in the southern Beaufort Sea. The Inuvialuit of Canada and the Inupiat of Alaska hunt the same polar bear population. The Inuvialuit hunt, however, is confined to certain seasons and the kills are recorded. The Inupiat hunt was not regulated, neither as to season nor to the number of animals killed. For example, there were no restrictions on killing cubs, females with cubs, or bears in dens. This placed a strain on the bear population in the border area between the two groups. To effect a solution, the Inuvialuit and Inupiat came together and worked out an agreement setting out regulations to create a sustainable bear population in the disputed area. Although it is still too early to see how effective the agreement will be, it is important because it is an example of two peoples coming together and, without outside help, agreeing to control hunts and the numbers and sexes of bears killed. It is hoped that such agreements might be reached in other parts of the world among indigenous peoples.35

An important international programme working for the protection of Arctic wildlife including the polar bear is the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program headquartered in Norway. There are also national government programmes. The Canadian Wildlife Service and the US Fish and Wildlife Service with its Marine Mammal Management Program in Alaska are both concerned with the conservation of polar bears.

Several organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOS), have stepped in to help. The International Bear Biology Association (IBBA) has promoted research on bears. Begun in 1966 with a small group of biologists meeting in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, Canada, IBBA now holds conferences every three years to ever larger groups of researchers. Other organizations, such as the Grizzly Bear Education and Conservation Campaign, Black Bear Awareness, Inc., the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, the Yellowstone Grizzly Foundation, Grizzly Discovery Center, the Black Bear Institute and the North American Bear Center, include in their mission statements a focus on educating the public about bears.

Larger organizations, some of them with international programmes, not only support conservation and habitat protection but also promote research and education. Such organizations are not totally preoccupied with bears and their survival, but many grant support to programmes that benefit bear research and conservation. These larger organizations include the WWF, TRAFFIC, USA, Defenders of Wildlife, The Wilderness Society, World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA), the National Wildlife Federation (NWF), the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), Wildlife Conservation International, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). The last named has set up species survival commissions on various endangered animals. It maintains separate commissions for individual bear species, such as the polar bear, spectacled bear and others.

Survival for several bear species is possible because bears are intelligent animals and masters at adapting to unfamiliar surroundings, but they must be given the chance to adapt. If some biologists are correct in proclaiming that in the future no wildernesses will exist, artificial ones must be created or preserved from the remains of those still existing. This will take not only money but education, dedication and sound management. Bears are known as a ‘flagship’ species: that is, if bears disappear they will take other species, both plant and animal, with them. The biodiversity of their former habitats will suffer. The creation of reserves that provide open corridors to other reserves is not enough. Reserves must be carefully managed and guarded against poachers, disease and overcrowding. There must be reserves not just for bears but for the entire megafauna necessary for bear survival. Several reserves are currently in various stages of completion but will they be large enough and will they be ready soon enough? Will the stamina and political will be there in the future to assure their continuance and pay for their sound management? As American ecologist Aldo Leopold pointed out in the early decades of the twentieth century, once man starts managing nature, he can never stop.

Bear-hunting in Finland today

I prefer to close on a story of hope. One recent bear reserve started in an unusual way. It began with the British Broad-casting Company (BBC) making a documentary on the origins of Paddington Bear. According to the story by Michael Bond, this bear travelled all the way from the dark jungles of Peru, ending up in Paddington Station with a sign around his neck reading ‘Please Look After This Bear, Thank You’. Since Paddington’s introduction in 1956, he has become famous all over the world. Although the documentary focused on the little stuffed bear from Peru, the show, hosted by actor Stephen Fry, brought the plight of the Peruvian spectacled bear to the attention of the British public. The Paddington Bear documentary was followed by a second documentary, also hosted by Fry, on the creation of a sanctuary for spectacled bears. The bear reserve was the brainchild of Nick Green of OR Media. While involved with the Paddington Bear documentary for the BBC, Green grew distressed about the plight of spectacled bears and their declining numbers. In his charming book Rescuing the Spectacled Bear: A Peruvian Diary, Fry writes of Green and the bear-saving expedition to deepest, darkest Peru:

We (and by ‘we’ I mean primarily Nick, who has led this initiative from first to last and without whose demonic energy and enterprise nothing would ever have been done) decided within a week or so of returning to England [after the first documentary], that another programme should be made devoted this time entirely to the Spectacled Bear and that a charitable foundation should be established for the purpose of rescuing distressed bears, purchasing land for their exclusive use and to pursue research into their numbers, their habitat, behaviour and future.36

The result was the Bear Rescue Foundation, which purchased land in Peru and hopes, with public contributions, to purchase even more land in order to create a reserve for spectacled bears. This is a start to counter the decline in this bear’s population in South America. The situation is now critical for spectacled bears. Despite the setting aside of Peru’s Manu National Park of 5,918 square miles (15,328 km2), declared an International Biosphere Reserve in 1977, the park and its spectacled bear population are under threat from cattle ranchers, gold miners, oil companies and timber interests that are all seeking access to its resources. These exploitative, short-sighted economic interests bode ill for the bears. But the formation of the Bear Rescue Foundation and of other organizations and foundations provides hope that it is still not too late to turn around the future of spectacled bears and of other bear species around the world. In his article ‘The Future of Bears in the Wild’, Servheen makes an astute observation while issuing a portentous warning: ‘Today, the bears that remain must contend with humans in order to survive, and humans never lose in competition but to themselves.’37

Bears and humans have wandered the earth together for millennia. Bears have lumbered around in our memories and our dreams. They have given us comfort and have inhabited our fears. Over time and among many peoples, humans have shared a kinship with bears. If we lose the bear we lose not only an important part of our rich natural heritage but a part of ourselves. Surely it is time to dust off Michael Bond’s original request and enlarge on it: ‘Please Look After These Bears. Thank You’.