3

Equal Representation’s Inexorable Clash with Political and Racial Equality

The campaign for direct election of the Senate progressed toward its final triumph at the same time as the last territories in the continental United States were converted into states. After the 1896 admission of Utah brought that touchy subject to a close, the early twentieth century saw the admission of Oklahoma in 1907, and then New Mexico and Arizona, both in 1912, just a few months before Congress sent the proposed Seventeenth Amendment to the states for their consideration. With the completion of the contiguous forty-eight states, the sometimes contentious politics of equal representation that attended state admissions was seemingly relegated to the pages of history just as the Senate was about to receive its democratic credentials for the new century in the form of popular election. And for the first half of the twentieth century, direct election of the Senate and women getting the vote through the Nineteenth Amendment in 1919 were the only significant developments in the advancement of electoral democracy in America.

Despite the revolutionary developments produced by the New Deal and World War II as concerned the power and policies of the US government, the institutions of democracy remained remarkably stable as the nation moved through the 1950s. But trouble—trouble that was always there but suppressed—was brewing. The early years of the Cold War era were accompanied by increasing confrontations over civil rights, culminating first in the Brown v. Board decision of 1954. Much like slavery and the build-up to the Civil War, a century later civil rights seemed to be increasingly at the center of almost everything. And in these struggles over civil rights the Senate would once again be a citadel for white supremacy as it, eventually alone among the institutions of national government, resisted political and social equality for African Americans.

Meanwhile, the issue of equal representation had not quite died with the completion of the lower forty-eight states. As the civil rights era was emerging, it intersected briefly with the final frontiers of American imperialism. The campaigns for and fights against the admission of Alaska and Hawaii long predated their admissions in 1959, and many of the usual arguments were employed for and against admission. Alaska in particular raised concerns because of its small population and lack of economic development. With a population of 228,000 in the 1960 census, Alaska would become the smallest state by a margin of some 60,000, displacing Nevada for that honor. Hawaii, with 642,000 residents, would come in a respectable forty-third. The fact that both were far removed from the contiguous forty-eight states was a novel concern, as were the indigenous populations of both territories, particularly Hawaii.

Efforts for statehood began in earnest after World War II, and President Truman called for admission of both territories in his 1946 State of the Union address.1 But resistance came particularly from the Senate, and sectional and partisan politics freely mixed. With civil rights controversies piling up together, from the Brown decision in 1954 to the events in Little Rock in 1957, and with Congress embroiled in struggles over modest civil rights measures in 1957 and 1959, the proposed admission of new states meant, much as it had a century earlier, a potentially new balance of power in the Senate. Of course, the states of the former Confederacy were badly outnumbered in the mid-twentieth-century Senate, but senators opposed to civil rights, whether from those states or others, had a powerful tool unavailable to like-minded members of the House of Representatives: the filibuster, backed by the Senate rule of procedure that required, at that time, two-thirds of senators to end debate on a measure under consideration. The addition of four senators who might support civil rights measures by helping to end filibusters endangered that vital source of minority power.2

Southern Democrats feared the admission of both these Pacific territories but seemed to be more alarmed by Hawaii because it would be the first majority-minority state and one likely dominated by Republican voters. And the party of Lincoln was still more committed, in words at least, to civil rights than were the Democrats. Alaska would certainly be a very northern state even if Democratic in its partisanship. Southern Democrats had a litmus test for any issue: How might the matter under discussion affect the balance of power on civil rights and the federal government’s ability to intervene in the politics of southern states? Both territories were a threat on that score. But the pairing of Republican Hawaii with Democratic Alaska—with a major historical irony in store for both parties—was part of the partisan politics that allowed both statehood measures to move through Congress.3 The nation’s Civil War past was not dead; it was not even past.

One Person, One Vote: The Inescapable Requirement of Modern Democracy Except for the Senate

The admission of Alaska and Hawaii came as the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren was about to confront a major issue that would put its decisions on a collision course with the logic of the Senate, even though the Senate and the apportionment of its seats based on state equality rather than state population were not the subject of controversy or any of the rulings. Logical minds no doubt continued to be disturbed by the odd nature of Senate representation, especially when highlighted by the admission of small-population states, but in the second half of the twentieth century it was representation in the House of Representatives that began to attract political and constitutional attention. The House had its own, and similar, representational problem, which became more acute as the country grew and urbanized. As the twentieth century proceeded, House districts in many areas of the country were becoming radically unequal in population.

Whereas the representational oddity of the Senate was an interstate phenomenon, the problem attached to the House was intrastate. That is, one could recognize the democratic flaw in the Senate’s equal representation by comparing New York and Delaware; to see the parallel problem in the House required a comparison of districts within one state, such as those within Tennessee or within California. It is worth a reminder that the seats for the House of Representatives are distributed or “apportioned” on the basis of population following the census and according to the Constitution’s stipulation that “Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective numbers.” After each state is awarded one seat, the rest are awarded by population following a formula legislated by Congress.4 But the Constitution says nothing about how the elections to fill those seats would be handled by the states.

From the founding forward, the basic structures of elections, the right to vote, and the power of a citizen’s vote had been under the control of state governments. The one national voting right was found in Article I’s provision that, when it comes to voting for the House, “Electors in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature.” Otherwise, voting rights were defined by state constitutions and state laws, which were given the power to prescribe “the Times, Places, and Manner” for national elections. Congress made little use of its ability to “make or alter such Regulations” created by the states.

The major congressional intervention came in the form of an insistence that all states that were apportioned more than one representative create single-member districts of contiguous territory. This stipulation began with the 1842 Apportionment Act. Prior to the single-member district mandate, a few states had used statewide at-large elections or multimember districts. But the single-member district requirement was not enforced, and the House agreed to seat more than one delegation elected by at-large systems. In 1872 they added that districts contain “as nearly as practicable an equal number of inhabitants.”5 This too was not enforced. Incorporated into apportionment acts up to and including the one from 1911, these specifications regarding single-member, contiguity, and equality were dropped in 1929, following a decade in which Congress could not agree to enact an apportionment.

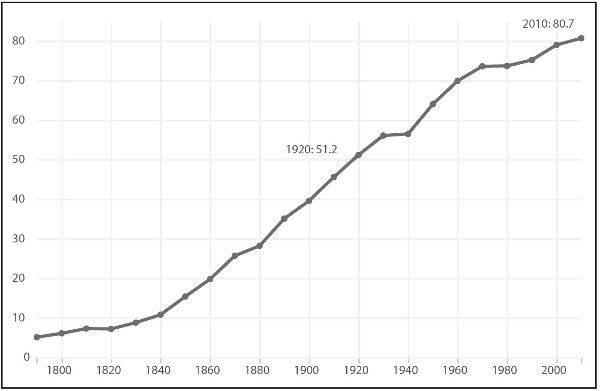

In the absence of any national control, many states produced increasingly unequal districts for the House and for their state legislatures, the latter of which were not under federal control anyway. This practice is often characterized as “malapportionment.” A relative term, malapportionment can refer to any inequitable method of distributing representation in a legislative body. In the context of early twentieth-century America, it was applied to districting that deviated substantially from population. Even if there was not at this time any constitutional standard, the distribution of House seats on the basis of the census and population was a pretty strong implication of equality. As well, some state constitutions stipulated districting based on population. But many were not putting that into practice. After World War II this was increasingly seen as a problem. Tennessee, for example, had not reapportioned its state legislature since 1901. Much of this resulted from the efforts of rural politicians and voters to preserve their power against the inexorable shift of population—documented by the census that was to determine reapportionment—to urban centers. That is what caused the deadlock in Congress in the early 1920s over reapportionment. The 1920 census showed, for the first time, that a majority (just over 51 percent) of the nation lived in urban areas. As late as 1890, it had been only 35 percent (figure 2). States north and south were guilty of apportioning legislative districts in favor of rural areas—and the California State Senate was by some measures the worst—but many of the most egregious cases were in the South.6

And southern redistricting practices were not just about the rural-urban divide but also about the suppression of Black voting. Some of the only locations where Blacks were able to vote in significant numbers were in the southern cities to which they moved as part of the Great Migration from the late 1910s into the 1950s. During this period, millions of southern Blacks moved north from predominantly rural areas, mostly to large cities in the Northeast and Midwest, such as New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Detroit. But they also concentrated in southern cities such as Memphis and Birmingham.7 The two trends converged: as the United States was changing from a rural to an urban nation, many of its cities were becoming home to more African Americans. Any form of electoral districting that disadvantaged city dwellers in general was going to disadvantage Blacks in particular.

Fig. 2. Percentage urban population in U.S. Census, 1790–2010

Source: US Census Bureau.

States were, in effect, replicating within their borders the kind of democratic distortion created by equal representation in the Senate at the national level. The Senate distortion was between small and large states, while districting within states often pitted small counties against more populous counties and, more generally, urban voters against rural ones. State assemblies often had large-population urban districts and lower-density rural districts. Many state senates were based on county boundaries. States sometimes drew on a logic that echoed that of the Great Compromise. Rural voters and the counties in which they resided (as natural political communities), in this view, required protection from the overwhelming influence urban voters and interests would have if state legislators adhered to numerical equality across districts.8

Significantly unequal districts appeared at all levels—in the US House of Representatives, state assemblies, and state senates—but the analogy to the US Senate and the Great Compromise was applied particularly to state senates. The implicit parallel was between the relationship of states to the Senate in the national Constitution and the role of state senators as representatives of counties in many states and state constitutions. In fact, in the 1920s, California, via a direct popular vote on a constitutional amendment, mandated that the state senate be apportioned equally by county: one county, one senator.9 This resulted in the effective disenfranchisement of most of Los Angeles, whose six million residents chose one state senator, the same as rural counties with populations as low as 14,000. While usually less egregiously malapportioned than many state legislatures, districts for the US House of Representatives also often varied significantly in population. And these house districts were drawn by the same state legislators who had been elected from often radically unequal state districts. The Supreme Court would later describe all this as “a crazy quilt without rational basis.”10

No matter how crazy or lacking in rational basis, the federal courts initially shied away from involving themselves with the cases brought by citizens in various states who felt such districting violated their state constitutions or national rights under the equal protection clause of the Constitution. As early as 1946, the Supreme Court decided that it should not wade into the “political thicket” of districting.11 Under prevailing constitutional doctrine at the time, apportionment and districting were political questions that were better left to resolution by the democratic processes at the national or state level. That is, certain disputes between the institutions of government or stemming from the electoral process were best resolved by the democratically accountable branches as questions of political judgment rather than constitutionality. Judicial intervention was possible but not prudent.

In the case of apportionment, aggrieved voters had to take their complaints to the politicians in their states, the ones who drew the electoral maps that were so biased. And for another sixteen years, the political question doctrine frustrated the movement to address this inequity. The initial constitutional breakthrough came with Baker v. Carr in 1962 when the Warren Court ruled that legislative apportionment was a constitutional issue that could be adjudicated in federal courts. The court’s decision was limited to this jurisdictional question and did not reach the substance of the case, which was about Tennessee’s apparent violation of its own constitutional provisions regarding apportionment of the state legislature.12 But the Supreme Court would soon be ruling on the substance of apportionment cases that were coming from dozens of states.

The first step forward in post-Baker jurisprudence came a year later, in March 1963, when Justice Douglas announced in Gray v. Sanders that “the conception of political equality from the Declaration of Independence, to Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, to the Fifteenth, Seventeenth, and Nineteenth Amendments can mean only one thing—one person, one vote.”13 Gray was about Georgia’s system of primary elections for statewide and federal offices, a system based on county units rather than population. As such the ruling against Georgia’s primaries did not directly affect apportionment for state legislatures or the House of Representatives. Nevertheless, the direction in which the court was heading seemed rather clear. Whether or not Douglas’s lineage of great texts really all pointed to this one inescapable conclusion is beside the point. Representative democracy had evolved in such a way that it was difficult to imagine and justify a different standard.

The following year the Warren Court applied the one person, one vote standard to the apportionment of districts for the US House of Representatives and state legislatures. In Wesberry v. Sanders, the court relied on the Constitution’s specification in section 2 of Article I that the “House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen . . . by the People of the several States” to apply this standard to the House. Those words meant, according to Justice Black’s majority opinion, “that, as nearly as is practicable, one man’s vote in a congressional election is to be worth as much as another’s.”14

The same degree of equality applied to state legislatures as well, this time via the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. The prohibition “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws” had lain effectively dormant from that amendment’s ratification in 1868 until 1954’s Brown v. Board decision on segregation in public schools. The Warren Court used it again to cement its constitutional revolution in political equality. In using equal protection to end malapportionment in state legislative districts, the court confronted a final major question: Could states have a second legislative chamber, analogous to the US Senate, that was apportioned on a basis other than population, such as by county, in a way that inevitably gave disproportionate influence to rural areas and voters? One of the six apportionment cases from 1964, Reynolds v. Sims, confronted this final question in a case from the state of Alabama.

No, was the court’s answer in an 8–1 decision. The Alabama state assembly might have more and smaller districts than its senate, but all assembly districts had to be equal to each other in population, and all senate districts had to be equal to each other as well. “We hold,” wrote Warren for the court, “that, as a basic constitutional standard, the Equal Protection Clause requires that the seats in both houses of a bicameral state legislature must be apportioned on a population basis. Simply stated, an individual’s right to vote for state legislators is unconstitutionally impaired when its weight is in a substantial fashion diluted when compared with votes of citizens living in other parts of the State.”15 More succinctly, and memorably, “Legislators represent people, not trees or acres. Legislators are elected by voters, not farms or cities or economic interests.”16 And, drawing on the words from a unanimous decision in 1960, the court argued: “The fact that an individual lives here or there is not a legitimate reason for overweighting or diluting the efficacy of his vote. The complexions of societies and civilizations change, often with amazing rapidity. A nation once primarily rural in character becomes predominantly urban. Representation schemes once fair and equitable become archaic and outdated. But the basic principle of representative government remains, and must remain, unchanged—the weight of a citizen’s vote cannot be made to depend on where he lives” because to “the extent that a citizen’s right to vote is debased, he is that much less a citizen.”17 Regardless of the security of its constitutional footing, the court’s grasp of the logic of modern democracy and its premise of political equality was unshakable and persuasive.18

More than once near the end of his career Warren deemed Baker v. Carr and the subsequent apportionment decisions down through Reynolds to be the most consequential of his tenure as chief justice, more important in his view than Brown v. Board of Education. While acknowledging the widely held opinion that Brown was “the most important case of my tenure on the Court,” Warren “never thought so.” Instead, “that accolade should go to the case of Baker v. Carr,” which led to one person, one vote.19 Taken as a whole, the apportionment decisions directly affected nearly every state and compelled all but immediate action to remedy disparities in representation for the House Representatives, state senates, and most state assemblies. The decisions elicited an uproar from many states, and from some members of Congress, but one that dissipated very quickly. While unpopular among many elected officials, and with huge ramifications for their political power and security, the decisions were generally popular with the public.20 Unlike some other Warren Court decisions that received hostile or more mixed public receptions, the application of one person, one vote—the idea that one’s vote should be equal to those of other citizens—made sense, and the injustices of malapportionment were too manifest. As one scholar put it, “Reynolds went from debatable in 1964 to unquestionable in 1968.”21

Measured in terms of immediacy and national impact, the apportionment cases were bigger than the school desegregation decisions, which, while morally profound, had limited effect on the problem at hand. But the two issues—Black civil rights and apportionment—were also closely connected logically, and in the mind at least of the great chief justice. Indeed, the connection was perhaps the main reason Warren accorded the apportionment decisions that lofty status. As the chief justice reasoned, “If Baker v. Carr had been in existence fifty years ago, we would have saved ourselves acute racial troubles. Many of our problems would have been solved a long time ago if everyone had the right to vote and his vote counted the same as everybody else’s. Most of these problems could have been solved through the political process rather than through the courts.”22

Warren was suggesting that apportionment, which was presented as a problem of overrepresentation of rural versus urban populations, was also an issue of race and civil rights. For example, during the court’s conference meeting on Baker, Justice Black noted that court intervention in malapportionment was a threat to white control in the South.23 The demographic forces that were increasing urban populations included the migration of Blacks to cities north and south. Malapportionment was another way to diminish the influence of African Americans. Even if relatively few southern Blacks had been able to vote prior to the mid-1960s, many of those who could, lived in cities.

If white supremacy was a mostly unspoken subtext of the apportionment cases, the US Senate was the elephant in the courtroom, especially in Reynolds. Having ruled unconstitutional the majority of upper houses in the country, and having articulated a compelling logic of democratic representation, Warren had to make the senatorial elephant vanish, or at least shrink it down to an ignorable size. In particular, the court was compelled to address the “so-called federal analogy” posed by state senates—that states should be required to have one chamber composed of equal population districts, like the House, and allowed one chamber, like the Senate, that is apportioned on the basis of, essentially, geography. “We . . . find the federal analogy inapposite and irrelevant to state legislative districting schemes,” concluded Warren for the court. “Attempted reliance on the federal analogy appears often to be little more than an after-the-fact rationalization offered in defense of maladjusted state apportionment arrangements.”24 States created counties, or other special lines that might be drawn to create unequal state senate districts, and these districts had no prior or independent status as political entities. This is unlike the original states that made up the United States and formed the country by their agreement as prior, separate, and sovereign governments and territories.

The court did not have to justify the US Senate’s apportionment. It is in the Constitution; by definition, it is constitutional. But Warren did discuss this, and in so doing perhaps weakened his own argument insofar as he had trouble coming up with a rational basis for the ongoing inequities of Senate representation:

The system of representation in the two Houses of the Federal Congress is one ingrained in our Constitution, as part of the law of the land. It is one conceived out of compromise and concession indispensable to the establishment of our federal republic. Arising from unique historical circumstances, it is based on the consideration that, in establishing our type of federalism a group of formerly independent States bound themselves together under one national government. Admittedly, the original 13 States surrendered some of their sovereignty in agreeing to join together ‘to form a more perfect Union.’ But at the heart of our constitutional system remains the concept of separate and distinct governmental entities which have delegated some, but not all, of their formerly held powers to the single national government. The fact that almost three-fourths of our present States were never, in fact, independently sovereign does not detract from our view that the so-called federal analogy is inapplicable as a sustaining precedent for state legislative apportionments. The developing history and growth of our republic cannot cloud the fact that, at the time of the inception of the system of representation in the Federal Congress, a compromise between the larger and smaller States on this matter averted a deadlock in the Constitutional Convention which had threatened to abort the birth of our Nation.25

Just as the court’s democratic theory of one person, one vote is difficult to dispute, its historical understanding of the founding compromises is sound. “But,” as one pair of scholars put it, “historical explanation is not contemporary justification.”26 Reynolds shows that equal representation in the Senate skates on the increasingly thin ice of the founding and tradition, something to be tolerated primarily because it was part of the original bargain, not so much for its current contribution or purpose, and despite the fact that it is increasingly at odds with modern democracy. In short, I agree with Supreme Court historian Lucas Powe that “the way Reynolds rejected the federal analogy was a direct slap at the United States Senate. . . . There is no other reading of Reynolds except one that concludes the United States Senate’s overrepresentation of the smaller states violates the nation’s principles of political fairness.”27

If the Reynolds decision did a solid job of explaining why state localities did not deserve representation divorced from population, it did not have much to say in support of Senate equality. In fact, insofar as the court implicitly criticized the consequences of unequal representation in state legislatures, it is not clear why its critique did not apply in equal measure to the US Senate:

The right of a citizen to equal representation and to have his vote weighted equally with those of all other citizens in the election of members of one house of a bicameral state legislature would amount to little if States could effectively submerge the equal population principle in the apportionment of seats in the other house. If such a scheme were permissible, an individual citizen’s ability to exercise an effective voice in the only instrument of state government directly representative of the people might be almost as effectively thwarted as if neither house were apportioned on a population basis. Deadlock between the two bodies might result in compromise and concession on some issues. But, in all too many cases, the more probable result would be frustration of the majority will through minority veto in the house not apportioned on a population basis, stemming directly from the failure to accord adequate overall legislative representation to all of the State’s citizens on a nondiscriminatory basis.28

The court’s logic notwithstanding, one person, one vote was mandated for every American legislative body except the US Senate, and that new constitutional standard was implemented only a few years after Alaska and Hawaii entered the union with their collective three representatives and four senators.29 As we have seen, in Reynolds Chief Justice Warren addressed the argument that almost three quarters of the fifty states were not party to the original bargain of 1787. Instead of predating the union, the subsequent states were creations of the national government. The consequences of the Great Compromise were replicated beyond the framers’ imagination as dozens of mostly small-population territories were admitted as states, ending with Alaska and Hawaii. And when judged against the new democratic standard of one person, one vote, equal representation in the Senate had become more egregious over time. It was a greater affront to political equality in the second half of the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first, than at its creation or in the 150 years between.

Who Is Underrepresented by Equal Representation in the Senate?

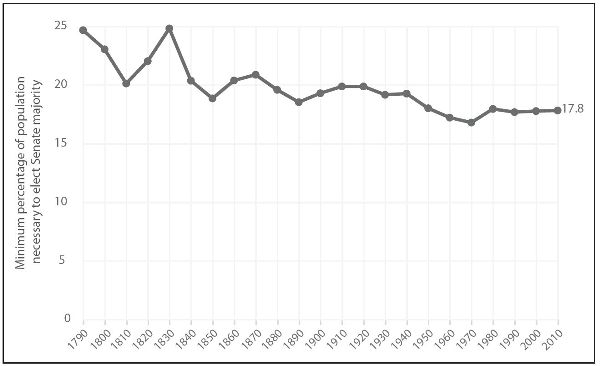

Because two senators per state is dictated by the Constitution, the “Senate is malapportioned by design.”30 Consequently, it is a bit odd to refer to the Senate as precisely that, even though by the standard of one person, one vote, it is arguably the most malapportioned legislative body in the world. There is more than one way to gauge malapportionment, whether in the United States or elsewhere. One of the most used is the minimum percentage of the population able to elect a majority of the legislative body.31 The lower the percentage that can elect a majority, the more malapportioned the legislature. And from the start, a small percentage of the population has been necessary to elect a majority of senators (figure 3). In the case of the Senate, one starts from the smallest state and counts up to the state that would produce a majority of the Senate (since 1960, the twenty-sixth from the bottom). The sum of the populations of those states can then be calculated as a percentage of the total national population. The percentage peaked in the 1830s at 24.8 percent. That was the highest percentage of the total population electing a majority of the Senate. Since then it has averaged just under 19 percent, and was 17.8 percent after the 2010 census. From 1790 through the 1940s, the average was 20.7 percent. From 1950 through 2020, the average was 17.6 percent.

As part of this evolution, the gap between the largest and smallest states has grown. The first census in 1790 revealed that Virginia, the largest state, had a population of 747,550, while the smallest, Delaware, contained 59,096, a ratio of 12.6 to 1. Based on the 2010 census, the same ratio between largest (California) and smallest (Wyoming) is about 66 to 1. The two, Virginia and California, were or are also by far the most populated states; that is, Virginia was significantly larger than the next state in population (a ratio of 1.72 to 1 compared to Pennsylvania) as is California (a ratio of 1.48 to 1 compared to Texas) today. If we take a group of states at the top and bottom to negate the effect of outliers like Virginia in its day and California in recent decades, we see the same increasing gap. For example, the ratio between the top five and bottom five in the 1790s was 7.5 to 1, whereas in 2010 the ratio of population between the largest five and smallest five was 33.5 to 1.32

Fig. 3. Senate malapportionment, 1790–2010

As noted, one voter in Wyoming is worth a bit more than sixty-six Californians when it comes to electing senators in their respective states. Wyoming, the Equality State, with the nation’s smallest population and an ironically accurate nickname, had 563,626 residents in the 2010 census, about the same as Fresno, California, that state’s fifth largest city. California, by far the largest state, had 37,253,956 residents. Starting from Wyoming and working up from the bottom, combining the less populous states until a California-equivalent population of over 37 million is reached, you have to go all the way to Connecticut, a total of twenty-two states, with forty-four senators. The voters of California get two senators while their equivalent, spread across twenty-two states, get nearly half the Senate. Add three more states and exactly half the Senate is represented by states accounting for only 16 percent of the nation’s population.33

If we start from the other direction, from the largest down, it takes only nine states to reach over one-half of the national population, represented by eighteen senators, less than one-fifth of that body. Sixteen percent of the country gets fifty senators while 50 percent gets eighteen. There are so many ways to parse this massive inequity. As another example, owing to the allocation system that assures each state at least one seat in the House of Representatives, seven states have one representative each, constituting a total of 1.6 percent of the House, but those same seven states constitute 14 percent of the Senate.34

Figures like the ones just offered are frequently cited to remind Americans of the scale of this distortion and representational injustice. And that distortion and the injustice it embodies are enough to condemn equal representation without further qualification. But comparisons of overall state populations obscure other distortions that add to the problems posed by Senate equality. As we have seen, the decisions from Baker through Reynolds were centered on the overrepresentation of rural interests and the underrepresentation of urban and minority populations, particularly African American. And just as the cases and the jurisprudence that led to one person, one vote concentrated on the manifest impact on urban voters of legislative malapportionment in the House and state legislatures, equal representation in the Senate is not so much about small versus large states as such as it is about rural versus urban voters and everything else that rough division has come to entail, particularly the power granted to mostly white voters in many smaller states relative to minority voters in larger states. As a result, political scientists and economists have left behind the traditional and familiar concerns about small versus large states and have focused on other effects. In an era of a more diverse, urban, welfare state, what are the distributive and representative consequences of Senate equality for the residents of more urbanized and diverse states? In short, Senate representation has become an ever more egregious and multilayered embodiment of the distortions of democracy that led to one person, one vote and the strict equality that applies to the districting of other legislative bodies in the United States.

A number of studies have tracked the bias of equal representation when it comes to such demographic characteristics as population density, race and ethnicity, and political ideology.35 As one scholar summed up, Senate apportionment “has increasingly come to underweight the preferences of ideological liberals, Democrats, African Americans, and Latinos.”36 As we shall see, this bias is directly related to the contemporary correlations between and among social demographics, partisanship, and urban versus rural residency. We will deal with ideology and partisanship later. Here I will focus on race and ethnicity. Just as there are several ways to measure malapportionment, there is more than one way to assess the relative representation of whites and minority populations in the Senate.

If we divide the fifty states by their percentage of African American residents, according to 2018 census estimates, there are sixteen states with Black populations under 4 percent. These states are nearly all smaller-population states, including six of the seven states apportioned only one representative each after the 2010 census.37 The sixteen states constitute one-third (32 percent) of the states and Senate but just under 10 percent of the national population, and not even 2 percent of the Black population. Politicians in these states simply do not have to consider the interests of Black voters. And they certainly do not elect Black members of Congress to either chamber. In the era of one person, one vote, no African American representatives or senators have been elected from these states during the forty-two years from the elections of 1968 through 2020.

Contrast that with the sixteen states with the highest percentage of African Americans, ranging from New Jersey with 13.6 percent to Mississippi with 38 percent. These states, with the exception of Delaware, have at least four representatives, and some are among the largest-population states in the country, including New York, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, Georgia, and New Jersey. With nearly 42 percent of the national population, they represent nearly 65 percent of all African Americans. And the difference in representation is astounding, at least in the House of Representatives. In the House, during the same forty-two-year period, these states produced seventy-seven Black representatives, who served a total of 508 terms! And this level of representation in the House came despite barriers and obstacles related to social inequality and district lines that have frequently been drawn to protect incumbents, who are often white.

While Black senators have been far and few between, the sixteen states with the highest percentages of African American residents produced four of the six African American senators elected since the implementation of direct election with the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913.38 Even if few Black senators have been elected in general, the white senators who were picked from the states with larger percentages of African Americans had to consider Black voters even if, as in some southern states during this time, they were often crucial components of the losing coalition. In most of the other states in this group, Black voters have frequently been part of winning coalitions.39 The Senate systematically underrepresents African Americans, and a significant percentage of the Senate can, from the perspective of electoral calculation, ignore them altogether. States with significant percentages of Black residents pay attention to their interests and, as one measure of this, elect Black representatives and even senators.

This same point can be extended to minorities more generally, especially with the inclusion of the large Latinx populations in many states. The sixteen states with the largest percentages of minority populations (averaging 46 percent, and ranging from Virginia with 35.5 percent to New Mexico with 62.5 percent), as before, are about one-third of the Senate but over 55 percent of the national population. In sharp contrast, the sixteen states with the smallest percentages of minority populations (averaging just over 13 percent and ranging from Maine with 4.9 percent to Utah with 19 percent) contain less than 16 percent of the nation’s total population. Lynn Baker and Samuel Dinkin broaden the point I have been making here by pointing out that the at-large nature of Senate elections (in contrast to House districts) further reduces the chances that minority populations will have an impact on Senate elections in most states.40

And, among other things, representation means money. Equal representation has been linked to smaller states receiving proportionally greater federal funding, even when controlling for levels of poverty.41 In their award-winning book on the policy consequences of equal representation, Frances Lee and Bruce Oppenheimer show that “small states benefit disproportionately, receiving higher per capital allocations of federal funds than large states across a broad range of domestic distributive programs, even after controlling for differences in state needs.”42 Particularly in areas of federal spending dictated by formulas written by Congress, such as transportation and community development, small states get proportionately more than large states. Many programs, for example, are designed with minimum guarantees. Such a provision typically dictates that each state gets at least 0.5 percent of the total allocation (and in the 2010 census, twelve states had populations less than 0.5 percent of the US total population).43 This showed up particularly clearly in discretionary grant programs designed by Congress in response to the 2009 recession. For example, in 2010, Alaska, Wyoming, and Vermont were the top three states in per capita grants, while Texas was 42 and California 27.44 The correlation is hardly linear, and things can shift from year to year, but in that same year the top fifteen states in per capita grants had an average population of 3.3 million while the bottom fifteen states averaged 7.5 million (the average population was about 6.2 million). In response to the Great Recession starting in 2007 and 2008, “the federal government has spent hundreds of billions to respond to the financial crisis, it has done much more to assist the residents of small states than large ones. The top five per capita recipients of federal stimulus grants were states so small that they have only a single House member.”45 Even after the attacks of September 11, 2001, the flood of money that was distributed to states for state and local security projects and programs displayed the same small-state and rural bias.46 Finally, congressional “earmarks,” those special and generally relatively small funding requests that benefit one state or House district, are “distributed relatively equally among Senators,” regardless of state population.47 No matter what programs are involved, this bias in federal spending is typically cited as a problem in and of itself, which it is. But, once again, the relationship to the demographics of small versus large states looms large: smaller and whiter states get a disproportionate share of federal dollars compared to the larger states with, typically, far greater percentages of minority residents, whose communities are relatively impoverished and underserved by a variety of state and national programs.

One Wyomingan, Sixty-Six Republican Votes: Equal Representation in the Era of Partisan Polarization

Of course, the distortions of equal representations are a problem regardless of ideology or partisanship. As just indicated, however, far more than during the Baker-Reynolds era, the vectors of urban versus rural, racial and ethnic identity, political ideology, and partisanship have converged. One of the signal features of contemporary American politics from the late 1980s onward has been partisan polarization.48 As the meaning of liberal and conservative became more consistent and persistent, and as it became increasingly clear that the Republican Party was the conservative party and the Democratic Party was the liberal party, politicians and voters sorted themselves accordingly. Perhaps one of the most striking aspects of this sorting is geographic. Americans are aware of red states and blue states, but in many ways the true divide is between rural America, dominated by Republicans, and urban America, dominated by Democrats—a divide between red states and blue cities, as one account put it.49 In an era of increasingly ideologically homogeneous parties and sorted voters, the representational consequences become increasingly stark everywhere in American politics, but particularly in the Senate.

Partisan sorting and polarization have created a very strong relationship between and among state size, urban population, and Senate elections, a relationship that was less pronounced before the 1990s.50 One way to see this is to categorize states by their relative balance of urban and rural population. We can start by dividing the states into three nearly equal groups by their percentage urban population—the least urban, moderately urban, and heavily urban—using the Census Bureau’s definition (figure 4). For each of the three groups we can determine the average state size. The group of least urban states had an average population of 2.53 million, compared to 5.44 million for the moderately urban states and 8.33 million for the heavily urban states. We can see, perhaps unsurprisingly, that state size and urban population are positively related. Each group represents almost exactly one-third of the Senate (34, 32, and 34 percent, respectively) but vastly different percentages of the total national population. The least urban states control thirty-four Senate seats but have only 16 percent of the total population, whereas the heavily urban states, which control the same number of Senate seats, have 52 percent of the total population (with the moderately urban states controlling thirty-two Senate seats and home to 32 percent of the population). The final step is to see whether there is a relationship between the state size–urban correlation and the partisanship of the senators elected from each group.

Fig. 4. Senate representation in an era of partisan polarization between urban and rural states, 1993–2019

Note: Least urban states average 54.5 percent urban; moderately urban states average 71 percent urban; heavily urban states average 87 percent urban.

In the fourteen elections from 1992 to 2018, the seventeen heavily urban states, representing a majority of the nation’s population, elected an average of nearly 70 percent Democratic senators. Reversing this, the seventeen least urban states produced just under 35 percent Democratic senators. Or, put the other way, they elected nearly 65 percent Republicans. In this way, seventeen rural states representing only 16 percent of the national population produced a full 44 percent of the Republican Senate membership during that quarter century. The 52 percent of the national population living in seventeen heavily urban states produced 47 percent of the Democratic Senate membership. Not surprisingly, the remaining sixteen states, the moderately urban group, fall between the least and heavily urban in terms of average size and the kind of senators elected. In the enduring landscape of polarized America, the Republican Party benefits from a highly efficient distribution of its voters in rural states. So it is not just California compared to Wyoming, it is across the board and involves relatively precise groups of voters with substantially different interests in government. In this way, the Senate has evolved into a nationwide gerrymander. To gerrymander is to draw “the boundaries of electoral districts in a way that gives one party an unfair advantage over its rivals,” according to Britannica, or, with a bit of added detail in Webster’s, “to divide (a territorial unit) into election districts to give one political party an electoral majority in a large number of districts while concentrating the voting strength of the opposition in as few districts as possible.”51 This has to be done with political force and creativity at the level of the US House of Representatives and state and local offices, especially because electoral districts beyond the Senate must be equal in population. In the US Senate, however, gerrymandering is not a political tool; it happens automatically if partisanship is correlated with geography. If ideology and partisanship did not overlap with the combination of urban–minority concentration and state size, there would be no clear Senate “gerrymander,” so to speak. But they do, they have for some time, and this is likely to endure and perhaps become ever more acute.52

This is the very kind of systematic distortion that the Supreme Court found unacceptable in the 1960s and that would in principle be unacceptable to most Americans. In short, urban and minority voters are dramatically underrepresented in the Senate, with stark consequences for the ideology, party, and policies with the most support in the national government.

Justifying, or at Least Excusing, Equal Representation in an Era of Democratic Equality

How can such radical disparities in representation be justified, or at least rationalized? Aside from equal representation being part of the founding bargain and part of the Constitution, which are blunt facts more than arguments, what are the contemporary justifications for two senators per state?

Equal representation is deeply ingrained in unexpected ways. For example, as a professor at the University of California, I have for decades taught classes on American politics filled almost exclusively with students from the Golden State. Whenever the Senate has been part of our considerations, I have included facts and figures about Senate apportionment and the degree of inequality it entails, mostly as a way to get students to think about something they take for granted. While generally aware that their state is large, Californians often seem surprised to learn that nearly one in every eight Americans is one of them. Few are aware how small, by comparison, the smallest states really are. Even so, almost every time this disparity suggests that a change in Senate representation might be justified, one or more students demur, asking “What about Delaware, or Rhode Island—what would happen to them?” The nature of the crimes that would be committed against these Lilliputians, once stripped of their senatorial protection, is a bit vague. When pressed, it pretty much comes down to federal funding and things like the location of the final resting place for nuclear waste. When asked, even the experts who have thought about such matters far more than my students have cannot do much if at all better. Justifications and rationales tend to trail off into excuses and pragmatics.

These justifications and rationales fall into four categories. The first line of argument invokes general principles of good government to which equal representation can be linked, however tenuously. For the United States, the principles of good government being invoked are a system of separation of powers with checks and balances, pretty much the central principle of the American system of government. This core principle is connected to equal representation through what might be labeled the Senate syllogism, which runs as follows: Bicameralism is a vital part of the system as a check on and refinement of legislative power; bicameralism is intended to prevent rash decisions and improve deliberation by dividing the legislature into two differently constituted chambers; equal representation is an important part of what makes the chambers different; therefore, equal representation preserves the benefits of bicameralism. This line of argument can acknowledge the democratic shortcomings of equal representation while asserting its value in the multifaceted Madisonian system of separated powers and checks and balances.53 That might be true, but equal representation just happens to be one way to create strong bicameralism. The Warren Court made it clear in the Reynolds decision that the application of one person, one vote to both chambers need not undermine the effectiveness of bicameralism:

We do not believe that the concept of bicameralism is rendered anachronistic and meaningless when the predominant basis of representation in the two state legislative bodies is required to be the same population. A prime reason for bicameralism, modernly considered, is to insure mature and deliberate consideration of, and to prevent precipitate action on, proposed legislative measures. Simply because the controlling criterion for apportioning representation is required to be the same in both houses does not mean that there will be no differences in the composition and complexion of the two bodies. Different constituencies can be represented in the two houses. One body could be composed of single member districts, while the other could have at least some multi-member districts. The length of terms of the legislators in the separate bodies could differ. The numerical size of the two bodies could be made to differ, even significantly, and the geographical size of districts from which legislators are elected could also be made to differ. . . . In summary, these and other factors could be, and are presently in many States, utilized to engender differing complexions and collective attitudes in the two bodies of a state legislature, although both are apportioned substantially on a population basis.54

While strong bicameralism might be a vital component of a separation of powers system, equal representation is not a necessary condition for the benefits of bicameralism. This argument is a defense of bicameralism, not equal representation as such. In fact, the costs of structuring bicameralism in this way might far outweigh the benefits.

The most direct and important contemporary argument is based on constitutional principle. Equal representation, it is argued, protects and preserves federalism, the constitutional division of power and authority between the states and the national government. As Misha Tseytlin argues, equal representation has been justified primarily by this precept, what he labels the “sovereignty protection hypothesis.”55 There are, however, two sides to the federalism coin: the preservation of the sovereignty granted states in the Constitution and the representation of states, as states, in the deliberations of the national government. Much has changed as far as the relative sovereignty of states, and the Seventeenth Amendment severed the link between senators and states as corporate entities. So one can argue that this line of argument has lost considerable force. In chapter 2, I argued that equal representation has been less about states’ rights and federalism or “sovereignty protection” and more about regional and partisan power. Senators from various states have used their voting power to advance their interests. In particular, small-state senators are rationally motivated to use their disproportionate voting power to obtain benefits and advantages for their states from the national government. That is, the “sovereignty protection” rationale is far more accurately seen, in Tseytlin’s terminology, as “augmented voting power,” augmented voting power that has been used at best incidentally in defense of federalism.56

Defense of small-state sovereignty would have involved fending off “vertical aggrandizement” by the federal government, that is, federal decision-makers taking “away the independent choice of individual states in order to increase their own power.”57 But the historical record on this is thin at best. For the most part, history records dozens of fights over material interests such as tariffs and hard versus soft money, often involving regional interests and coalitions.58 These conflicts are about what Tseytlin labels “horizontal aggrandizement,” which happens when “any subset of states” uses “federal power to impose those states’ preferences on citizens in other states.”59 Even the momentous events leading to the Civil War were about the extension of slavery or fugitive slave laws, not state sovereignty as such.

Small states have not been the particular guardians of federalism any more than large states. For the most part, states of all sizes have been more interested in using their power in the Senate, whether they are under- or overrepresented, to advance a variety of interests, mostly dictated by the partisan alignments of the day rather than by a principled commitment to state sovereignty or any other constitutional tenet. It has become nearly impossible, if it was ever at all clear, to separate arguments about the principle of federalism from arguments about power.

Nevertheless, a third line of contemporary argument embraces rather than evades the idea that equal representation is about political power. “Without [equal representation], wealth and power would tend to flow to the prosperous coasts and cities and away from less-populated rural areas,” according to political theorist Stephen Macedo.60 “Cities already are the homes of America’s major media, donor, academic and government centers,” argues Gary L. Gregg II, another political scientist. “A simple, direct democracy will centralize all power—government, business, money, media and votes—in urban areas to the detriment of the rest of the nation.”61

This argument seems to suggest that the US government can or should stem the tide of history. The movement of people and resources from rural to urban areas has happened regardless of political boundaries and systems of representation. That flow is a basic fact of modern civilization. What, precisely, can a government—particularly an explicitly limited and federal one like that of the United States—change about that? So, to be precise, such arguments must be referring to the use of the wealth and resources distributed by the government, as opposed to the largely market-driven distribution of economic power more generally. Indeed, the implication is that rural areas are entitled to use overrepresentation to capture government power and resources to offset market forces that supposedly advantage cities in population growth and material wealth. Which is, of course, exactly what happens. Small states often get more than their proportional share of federal funds.

This small-state bias in federal funding has been a source of some bemusement and ridicule, as the ire of red state Republicans over “big government” and “welfare” from Reagan onward is somewhat at odds with the actual distribution of federal revenues to smaller Republican states. The main point, however, is that, regardless of party or ideology, it is not at all clear how this would change were Senate representation to change, except by elimination of some or all of the disproportionate advantage to smaller states. It would not affect, and should not affect, other national policies. Most federal spending, for example, is dictated by entitlement programs in the areas of health care, welfare, and veterans. Such programs are tied to individual characteristics. One is or is not, for example, a veteran who qualifies for one or more such benefits. The geographic distribution of veterans or senior citizens determines the distribution of these sorts of entitlement checks from the federal government, not the representational power of the states, which, as we have seen, does affect some other government programs.

The political power argument speaks to some general concern about representation of interests but has no standard for fair representation. At what point does overrepresentation become absurd? How relatively small, one might ask, do small states and rural populations have to get before concerns about their well-being become ludicrous? Moreover, even if all the wealth were piled into urban areas, surely that would not mean that Wall Street billionaires would have the same interests as immigrant hotel workers in New York City. Donald Trump lived in Manhattan; Warren Buffett lives in Omaha. The Heritage Foundation, Chamber of Commerce, and Club for Growth are all in the city of Washington, D.C., but, as conservative as they are, it is not clear that they represent the geographic interests of rural areas. Instead, such well-organized groups and wealthy allies in urban areas depend on the overrepresentation of conservative voters residing in those states to elect Republicans; that is what they care about and attend to.

In the end, this concern for rural interests essentially replicates the arguments that failed before the bar of the Supreme Court in the 1960s apportionment cases. Any changes wrought by one person, one vote at the state level were fair and did not result in the demise of rural areas. As well, it is not clear why the rural areas of Wyoming deserve more representation than the rural areas of California, Texas, or New York. This highlights the point that one should not conflate federalism and equal representation. A robust version of the former can exist comfortably without the latter and is not dependent on it. If states, as states, have an interest in the maintenance of a particular division of labor between states and nation, then the numerical basis of their representation is not an essential factor. If anything, their mode of selection is. That is, the selection of senators by state legislatures kept them more tied to the corporate interests of their states, but the Seventeenth Amendment took care of that.

The final line of argument in support of equal representation is the trump card of practicality or pragmatism.62 One can concede the democratic inequities of equal representation and still deem it a “tolerable imperfection” for largely pragmatic reasons because the costs of changing it are perhaps impossibly high and the benefits that might ensue perhaps rather small.63 Ultimately, while almost any constitutional amendment is an improbable undertaking, equal representation is especially unlikely to arouse the public passion that would be requisite even to get the Sisyphean boulder in motion. Political theorist Stephen Macedo sums up the case succinctly: “Equal representation of states in the Senate is a singularly unlikely candidate for mass political mobilization for at least three reasons: it has various respectable rationales, it is deeply entrenched constitutionally and therefore would be very costly to change, and even if it does contribute somewhat to injustice it does so without embodying and expressing direct moral insult (like racial discrimination).”64

Two out of three isn’t bad, but Macedo is simply wrong on the last point, and it is by far the most important. As we have seen, Senate representation is a structural form of racial and ethnic discrimination that has no contemporary parallel. Short of an improbable and dramatic reversal of demographic trends and projections, equal representation will continue to underrepresent minorities substantially and systematically. This underrepresentation will continue to result in disadvantageous partisan alignments and patterns of institutional control, which in turn will lead to policy choices that fail to advance their interests. Viewed from the flip side of this coin, equal representation can be seen as “affirmative action for white people.”65 Moreover, discrimination against minorities highlights the “moral insult” of equal representation, but such disparate effects of the representational distortion are part of the more general violation of one person, one vote. The violation of that principle is so glaring that an inquiry into its actual or differential impacts is unnecessary, however important those are. In the end, this is primarily a normative question of democratic fairness, and the various arguments mustered in its favor cannot overturn the democratic indictment of equal representation. In fact, in the twenty-first century, one could argue that the distortion between equal representation and democratic values is far sharper, owing to the principle of one person, one vote and the underrepresentation of urban and minority voters, than was the clash between democratic values and state selection of senators in the early twentieth century leading to the Seventeenth Amendment. In this case, however, and perhaps unlike in the case of the Seventeenth Amendment, one could make an argument that the elimination of equal representation would have a profound impact on American politics.

Equal representation’s violation of one person, one vote is bad enough. As we have seen in chapter 2 and discuss more in a later chapter, senators and others compounded the offense by transmuting equal representation into a general principle of minority rights. In turn, equal representation and minority rights have been used to defend the various forms of minority power in the Senate’s rules of procedure, specifically those that allow its members to filibuster and empower a minority of senators to delay or thwart altogether what the majority seeks to accomplish. Before we get to the history and impact of the filibuster and supermajority cloture, however, we need to understand another fundamental element of the Senate’s constitutionalism, one that, like equal representation, has been used to support and justify the filibuster. This feature, the Senate’s self-conception as a “continuing body,” links that institution’s longer and staggered terms to the practice of extended debate and supermajority cloture in the Senate.