4

The Right of the Living Dead

Staggered Terms, Continuing Bodies, and Constitutional Myths Senators Tell Themselves and America

There could be no new Senate. This was the very same body, constitutionally and in point of law, which had assembled on the day of its meeting in 1789. It has existed without any intermission from that day until the present moment and would continue to exist as long as the Government could endure. It was emphatically a permanent body.

—SENATOR JAMES BUCHANAN, 1841

Because only one-third of the Senate is up for reelection every two years, the Senate is said to be continuing, permanent, perpetual, or undying, to the point that scholars and politicians have claimed it is the same Senate that first met in 1789. Unlike the House, “the Senate . . . is a continuing body,” wrote George Haynes in his 1938 history of the Senate. From the first session, he continued, there has “never since been a time when the Senate as an organized body has not been available, at the President’s summons or in accordance with the terms of its own adjournment, for the transaction of public business.”1 Staggered terms—any arrangement of terms of office so that not all members of a body are appointed or elected at the same time—are one of the constitutional provisions that distinguish the Senate from the House and are the foundation for the notion that the Senate is a continuing body. As equal representation became the foundation for the Senate’s self-conception as the constitutional bastion of minority rights, staggered six-year terms were being used to add another element to the Senate’s perceived exceptionalism. The Senate, with its longer term and higher age requirement, is not just the older and wiser chamber of Congress, it is immortal!

Staggered elections for the Senate, whatever their intended effect, create a continuing body in the literal meaning of the term: a body whose membership is subject to only fractional change at any point in time. This is “continuing body” as a simple adjective or descriptive fact. But senators developed the mere fact of continuity caused by staggered elections into a constitutional self-conception and set of practices, such that the actions of past senators could and should bind or restrict current members of the body. This is continuing body as constitutional doctrine and practice, which applies particularly to that body’s rules.2 If the Senate never dies, then neither do its rules. As journalist William White put it in his mid-century history of the Senate, “And since, unlike the House, the Senate is a continuing body, never ending and never wholly overturning from one Congress to the next, the Senate rules go on immutable from one Congress to another. It is not necessary to renew or continue them; there they stand as unshakable in fact, almost, as the Constitution itself.”3 With less poetry and more precision, Senator Robert Byrd said much the same thing: “The United States Senate is an unbroken thread, running from our time back to its first meeting in New York in April 1789. By this I mean the Senate is a continuous body. While the entire House of Representatives is elected every two years, only one-third of the senators run at each biennial election. Since two-thirds carry over, our rules are continuous and do not have to be readopted at the beginning of each Congress.”4

The Senate harboring a self-conception as a continuing body as part of its tendency to institutional aggrandizement is in and of itself harmless and unobjectionable. The problem comes when the self-conception is turned into an implied constitutional restraint, such that the actions of past senators bind or restrict current members of the body. In particular, the notion of the Senate as a continuing body has been the chief reason, as the White and Byrd quotations indicate, that the Senate does not vote on its rules of procedure at the start of each Congress as the House does. In the House, the new majority votes on and sometimes modifies that chamber’s rules. In the Senate, no vote is taken automatically. Once a Senate tradition, this practice of not voting on the rules at the commencement of a new Congress was in 1959 turned into one of the rules—that is, another rule that would not be voted on by future Senates. This was done as part of a compromise to appease southern Democrats wanting to protect the particular rules that allowed them to filibuster civil rights legislation. The continuing body idea is also an important part of the rationale for a supermajority threshold of two-thirds of all voting senators needed to cut off debate on proposed changes in Senate rules of procedure. This is the connection between, or leap from, continuity as mere description to continuity as doctrine. The constitutional construction of the continuing body doctrine has served as another barrier to changing the rules of the Senate generally but particularly the supermajority cloture provisions of Rule XXII after they were created in 1917. The continuing body doctrine helped to elevate Senate rules and the filibuster to the status of higher law, akin to, if not quite part of, the Constitution.

Thus, not only did the continuing body doctrine get written into Senate rules as part of the Senate’s long history of filibusters in support of white supremacy, the doctrine itself is little more than a self-serving mythology based on a misinterpretation of the purpose of staggered terms in the Senate. The links between the Senate as a continuing body, the intentions of the founders, and the Constitution are, in fact, quite ironic. The debates at the 1787 Constitutional Convention make no mention of the Senate as a continuing body. “Permanency” and “duration” were used in reference to one thing only: the length of senatorial terms. And those were as often a source of apprehension as they were of celebration. Widespread concerns about a Senate aristocracy, including the fears of several delegates to the convention that a permanent aristocracy would entrench itself in a new national capital, throw cold water not only on the idea that the Senate was intended to be the bastion of minority rights but also on the notion that a continuing body was part of the founders’ grand design. But that is the least of it. This chapter reveals the origins of the continuing body mythology by exposing the deliberate misinterpretation of the purpose of staggered terms, criticizes the Senate’s use of this pretension, and shows how this specious concept has been used to protect and elevate the status of Senate rules, particularly the ones that allow for minority obstruction.

Why Does the Senate Have Staggered Terms?

We take staggered Senate terms for granted, but why were they included in the Constitution? As we have seen, the structure and composition of the Senate was the most contentious matter debated and resolved at the Constitutional Convention. And staggered Senate terms are on any scholar’s list of the key decisions of 1787 that made the Senate the Senate. Despite their importance in the architecture of American bicameralism, however, little scholarship exists on the origins and purpose of staggered terms for the US Senate.5 Instead, historians, political scientists, and journalists alike have repeated a conventional wisdom in a matter-of-fact manner that draws on assumption more than evidence. This dominant perspective portrays staggered elections as part of the framers’ intent to create an insulated, stable, deliberative—and thereby continuing or permanent—Senate. For example, the authors of a recent history of the Senate claim that the framers “decided that only one-third of the senators [would] come up for election each two years, further to insulate the Senate from popular enthusiasms or turmoil.”6 Almost ninety years earlier, historian Lindsay Rogers wrote much the same thing, as did many others in between.7

For example, “By requiring only one-third of the Senate to seek reelection every two years,” according to one congressional scholar, “the framers hoped that short-term fluctuations in public opinion would be leveled out in the Senate, allowing only enduring shifts in sentiment to take hold.”8 Robert Caro, in perhaps the bestselling book on the Senate, writes that “the Framers armored the Senate against the people,” and that, on top of state selection and long terms, staggered elections “would be an additional, even stronger, layer of armor.”9 Prominent American politics textbooks interpret staggered terms as “intended to make that body even more resistant to popular pressure” and part of what insulates the Senate “from momentary shifts in the public mood.”10 To my chagrin, my earlier work on the creation of the Senate offers another example.11 In this way, selection by state legislatures, six-year terms, and staggered elections almost always have been thought of and portrayed as a harmonious package to create a less democratic upper house. Staggered terms have typically been an implicit part of every cliché about the Senate as the “world’s greatest deliberative body” that “cools the coffee” brewed by the House. And there is an ahistorical quality to many of the assertions regarding the Constitutional Convention’s use of staggered elections as if they emerged ex nihilo in Philadelphia as a “solution” to the problem of complete turnover of the Senate12 instead of seeing staggered terms as a familiar practice from early state constitutions that might have had a different or more complicated function.13

This conventional interpretation has, however, little basis in the origins of and intention behind the Senate’s staggered terms. My argument is not that these and other similar characterizations are wrong in their implications about the potential effects of the combination of long and staggered terms. I show that they are misleading and inaccurate as far as the primary intentions and political interests that led to the inclusion of staggered terms for the Senate in the Constitution.

Where, then, did staggered terms come from, and why were they added in this specific way to the Constitution? As I lay out in detail below, staggered terms were (1) in the revolutionary era, a mechanism to ensure “rotation,” or democratic turnover, (2) added to the Constitution as part of a compromise to assuage opponents of an insulated Senate and obtain a majority in support of a long term for that body, and (3) portrayed during ratification as a form of rotation that counteracted the perceived dangers of the long term and a Senate aristocracy. Whatever the effects in practice, staggered terms were intended primarily to mitigate the potential dangers of a legislative body with long individual tenure by exposing it to more frequent electoral influence.14

The irony is that staggered elections, a category of rotation intended to disrupt the accumulation and perpetuation of institutional power, came to be seen as part and parcel of the Senate’s conservative purpose and produced the notion of an undying Senate or continuing body. More generally, seeing staggered terms as a form of electoral accountability, as a form of rotation, reminds us of the complexity of the Senate’s creation. The Senate was certainly intended to be the more conservative or undemocratic of the two legislative chambers, but not every aspect of its construction fits that mold. The combination of long terms and staggered elections evinces the framers’ efforts, with both abstract principles and political necessity in the mix, to balance stability with responsiveness in the design of republican institutions.

“Rotation” in the Late Eighteenth Century

In the years leading up to the Constitutional Convention, including the wave of state constitutions written in the 1770s and 1780s, staggered terms—the phrase was not used in this period—were one of a set of mechanisms used to create what was called “rotation.” In discussions of the tenure of any governmental office, the term “rotation” was invoked with some regularity to refer to the frequency with which the membership of an institution would be subject to change in whole or in part. “Rotation” was about devices that ensured regular turnover in officeholders and encompassed two approaches: provisions that limited reeligibility for office (that is, forms of what we now call term limits) and provisions that staggered the terms of membership in legislatures or other governmental bodies by dividing the membership into groups or classes to be selected in different years.15

In his 1776 “Thoughts on Government,” John Adams endorsed rotation, in the form of term limits, but annual terms held a higher status, “there not being in the whole circle of the sciences, a maxim more infallible than this, ‘Where annual elections end, there slavery begins.’”16 Annual elections, the paramount mechanism of democratic accountability in the revolutionary era, were frequently paired with eligibility rotation as a powerful check on governmental power. For example, the Articles of Confederation restricted delegates to Congress to serving no more than three years of any period of six, in addition to annual terms. In combination, short terms and eligibility restrictions together ensured rotation.

Unlike limits on reeligibility, rotation in the form of staggered elections could be applied only to chambers with terms greater than one year, and even going into the summer of 1787, annual elections were still the norm. Along with the Congress of the Confederation, ten states had annual elections for their lower house. Two, Connecticut and Rhode Island, held elections every six months for theirs. Only South Carolina had two-year terms for its general assembly.

Nevertheless, the revolutionary and founding era saw a move away from the viselike grip of annual elections. Even many champions of annual elections for the lower house acknowledged the virtue of balancing the kind of electoral check one-year terms represented with the accumulation of wisdom and experience and at least limited insulation from popular pressure. In the colonial era most upper houses were councils—some with indefinite appointments—that combined executive and legislative functions. The new state constitutions created upper houses that were more democratic in their selection, more clearly separated from the executive, and with longer terms than the assembly.17 The innovation of legislative senates with longer terms was tied to rotation in every case except Maryland, which also featured a system of electors to pick its senate.18

The scholarship on state constitutions does not spend much time on staggered elections for the new senates, but several historians imply that upper chamber rotation was to enforce turnover and electoral accountability.19 Perhaps it was self-evident given the context. With the lower house of nearly every state elected for one year only, no rotation was required. This implies quite directly that these state constitutions, aside from Maryland’s, were trying to combine a longer term in the upper house with turnover and an electoral check. In other words, the virtue of a longer term for some positions was to be balanced by rotation in the form of staggered elections.

A few state constitutions, including those of Virginia and Pennsylvania, provide contextual evidence for staggered terms as a form of rotation, but Delaware serves as a telling example. Its 1776 constitution created a “Legislative Council” composed of three councilors elected from each of the three counties that made up Delaware. These nine councilors served three-year terms, but one councilor from each county would be rotated out each year.20 Insofar as the lower house, the assembly, was elected to annual terms and even the executive privy council had two-year terms with rotation and limits on reeligibility, it is difficult to see the rotation in the legislative council as anything but that, especially as it was rotation within each county’s group of three councilors. In this way, the counties would be able to influence the nature and direction of their representation in the upper house every single year.

Rotation and the Senate at the Constitutional Convention

Given this backdrop of recently formed and tested state charters, the delegates to the convention were familiar with staggered terms as a form of rotation for offices with longer terms. Its ultimate application to the proposed national Senate, therefore, is not surprising, but neither was it automatic. When the delegates added staggered terms, they did so as part of a compromise to balance the longest Senate term attainable with a form of rotation.

As I showed in the first chapter, the Constitutional Convention opened with consideration of the so-called Virginia Plan or Randolph Resolutions, which were largely the work of James Madison. He was the foremost advocate for an independent and stable Senate, one characterized by experience, knowledge, detachment, and elevated selection. If staggered elections had been part of a plan for augmenting the continuity or detachment of the second branch, it is probable that Madison would have included such a provision in the Virginia Plan, especially insofar as Virginia’s state senate had a four-year term, with one quarter going out every year. Madison was, however, an avowed proponent of the Maryland senate with its term of five years—the longest of any state—and no rotation.21

Only two weeks into the proceedings, the convention delegates first considered the periods of service for both chambers. This discussion took place before the delegates got bogged down in the debates over equal and proportional representation and the interests of small and large states, but it followed the unanimous decision on June 7 in favor of state legislatures selecting senators. On June 12, long terms for both chambers won decisive initial victories, with three-year terms for the House prevailing 7–4 and seven years for the Senate by 8-1-2, with no mention of any type of rotation.22

The first proposal for rotation of any kind did not come until several days later, and it was for the House, not the Senate. On June 21, when the delegates reconsidered the House term, some pushed for a shorter tenure than three years, citing in some cases the annual elections that were still common at the state level. Delaware’s John Dickinson favored the three-year House term agreed to earlier but argued against the “inconveniency of an entire change of the whole number at the same moment” and “suggested a rotation, by an annual election of one third.” In a clear splitting of the difference, three years was struck by a decisive vote in favor of two years, which presumably did not require any rotation but was long enough to be practical, in light of the distances representatives would have to travel. It bears repeating that the first recorded mention of staggered terms occurred in a proposal for the lower chamber and in the spirit of the usual meaning and purpose of rotation.23

The final decision on Senate terms was more difficult and protracted. Despite the initial agreement by the 8-1-2 vote, many delegates had concerns that seven years was too long. When the delegates returned to the question of Senate terms on June 25, a few days after having reduced the House term to two years, Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts proposed four years instead of seven, with “1/4 to be elected every year.”24 This was countered by a proposal for seven years but also with staggered terms. North Carolina’s Hugh Williamson then suggested six years as more convenient for rotation. But the delegates did not vote to add staggered terms at this point. They took the first step of striking seven years by a 7-3-1 vote. Long terms continued to do poorly, with six and five years falling short on the same 5-5-1 votes.25

The next day, Gorham tried to end the gridlock by proposing six years, but with the additional provision of “one third of the members to go out every second year.” Delaware’s George Read still favored life appointments, but “being little supported in that idea . . . was willing to take the longest term that could be obtained.” And so he countered with nine years and one-third rotation.26 Insofar as he favored life appointments to the Senate, Read’s inclusion of rotation was a recognition of the political need to offset long terms with refreshment and renewal. After some debate, nine years with rotation lost 3–8, but six years with rotation won 7–4.27 With the earlier opposition to six and even five years, it is clear that rotation helped seal the deal, and rotation was about change, not continuation. It was a way to temper long terms of service with fresh blood.28

Although the convention records show extensive debate about the purpose and merits of a long Senate term, only a few comments such as Read’s conveyed an explicit rationale for rotation. With one exception they concern balancing a long term with electoral accountability. For example, Roger Sherman sought the shortest term feasible and argued that “the two objects of this body are permanency and safety to those who are to be governed. A bad government is the worse for being long. Frequent elections give security and even permanency. . . . Four years to the senate is quite sufficient when you add to it the rotation proposed.”29 Sherman contrasted the “permanency” of four-year terms (versus his state’s annual elections) against the turnover provided by rotation.

In the last recorded speech before the final votes on Senate term length, Pennsylvanian James Wilson showed how rotation was more a compromise than a vital principle. Wilson cited the importance of some permanence or stability in the government for treaties and diplomacy (indeed, a Senate with a long term might even be a match for a foreign monarch): “The popular objection agst. appointing any public body for a long term was that it might by gradual encroachments prolong itself first into a body for life, and finally become a hereditary one. It would be a satisfactory answer to this objection that as 1/3 would go out triennially, there would be always three divisions holding their places for unequal terms, and consequently acting under the influence of different views, and different impulses.”30 The one direct reference to rotation as a way to stabilize Senate membership came from Edmund Randolph, who, just after Gorham’s proposal for four-year terms with one quarter rotation, “supported the idea of rotation, as favorable to the wisdom and stability of the Corps. [which might possibly be always sitting, and aiding the executive].”31 Randolph’s comment invoked the Senate’s as yet undefined but anticipated relationship with the executive, particularly in foreign affairs and the business of treaties.

Even with Randolph’s invocation of wisdom and stability, the framers’ deliberations and actions show that they primarily viewed and used Senate rotation as a tool for fostering this body’s electoral accountability rather than institutional autonomy or insulation in the antidemocratic sense. Staggered terms became part of a compromise, a means to an end, a way to balance the merits of long terms against the threat of permanency. In short, one side, the staunch advocates of a republican Senate, got as long a term as possible, and some who feared an entrenched aristocracy or needed some degree of compensation or political cover got rotation as a check.

Staggered Terms in the Ratification Debates

The structure and powers of the Senate were significant controversies during ratification, including the six-year term, which many conventioneers and commentators felt was too long. Staggered elections for the Senate were less of a topic, but evidence from the various debates during ratification, treated with appropriate caution, underscores that its main purpose was to offset concerns that attended long terms.

Annual elections and rotation featured in the critiques of the proposed Constitution. Some of its opponents thought two years was too long a term for representatives and still favored the provisions in the Articles of Confederation that combined annual terms for delegates to Congress with the additional restriction of serving no more than three years of any period of six, which was a different type of rotation in the form of term limits. Indeed, the length of House and Senate terms were among the more frequent criticisms of the proposed Constitution, with antifederalists often suggesting one-year and four-year terms instead.32 And such was antifederalist fear of a detached Senate aristocracy that staggered elections were not reassuring to all. A delegate to the Massachusetts convention referred to staggered Senate terms as “but a shadow of rotation.”33 Brutus, the premier antifederalist essayist, referred to the Senate’s staggered terms as a form of rotation, but condemned the absence of eligibility rotation and called for a reduction to a four-year term.34 Yet even if some thought it an insufficient form of rotation, antifederalists neither criticized nor sought to repeal the provision for staggered terms.

In turn, advocates of ratification invoked staggered terms as a powerful check on a permanent or insulated Senate. Many pro-ratification delegates argued against term limits, the other form of rotation, and against recall, but defended staggered terms for the Senate as a different and necessary type of rotation. My search of the debates at the state conventions produced seventeen such endorsements of staggered terms by a total of eleven proponents of ratification.35 All the references characterize staggered terms as a safeguard against a “perpetual” Senate, a Senate aristocracy. Subjecting one-third of the Senate to election every two years would keep senators attentive to their states and bring in new sentiments about government and policy.

In Massachusetts, Fisher Ames called rotation a “very effectual check upon the power of the Senate.”36 North Carolina federalist James Iredell argued that the newly elected one-third “will bring with them from the immediate body of the people a sufficient portion of patriotism and independence” to thwart any dangerous alliance between the executive and the Senate.37 “By constructing the senate upon rotative principles,” said Charles Cotesworth Pinckney to his fellow South Carolinians, “we have removed . . . all danger of an aristocratic influence” while allowing the long term of six years to provide the “advantages of an aristocracy,” including wisdom and experience.38 Finally, Alexander Hamilton endorsed staggered terms at the New York convention, arguing “that safety and permanency in this government are completely reconcilable.”39 The man who, at the center of his major speech at the Constitutional Convention, proposed life terms for senators likely would not have thought of staggered terms as a way to increase Senate “permanency.” Instead, as he put it, two equally important principles—the safety of electoral accountability and the detached judgment and experience provided by “permanency”—could be harmonized by balancing long terms with rotation.

Stretching from the state constitutions through ratification, rotation in the form of staggered elections had one central purpose, ensuring the turnover of officeholders. Staggered terms were seen by some as more dimensional in their intended effects than, for example, term limits, a blunter form of rotation. In a few instances, proponents portrayed staggered terms as a form of accountability that also preserved institutional knowledge or continuity, even if this perspective rested on an implicit assumption that massive or even complete turnover would occur in bodies without staggered terms. But the argument for preservation or continuity of knowledge was not antidemocratic in the manner typically implied by the conventional view of staggered Senate elections. In light of the evidence above, the general argument that the framers added staggered terms to further insulate the Senate and further distinguish it from the democratic House is unsustainable. When joined together, however, long and staggered terms certainly had multiple effects. Even if the intentions and politics of the convention led to the addition of staggered elections to temper long terms, the combination produced a body, that in comparison to the House, never would be subject to the same degree of potential electoral change.

This chapter provides another illustration of the complexity of the Senate’s origins.40 The Senate was, of course, the object of the Great Compromise that tried to blend Madison’s Senate of far-sighted statesmen with equal and direct representation of states. Placed at the intersection of several constitutional vectors or tensions—responsiveness and deliberation, legislative and executive powers, states and nation—the Senate reflects the multiple forces and goals at work in its construction. The central elements of the Senate’s composition as ratified in 1789—selection by state legislatures, six-year terms, and staggered elections—were a package that embodied these various ideas and interests. By contrast, the common understanding of Senate staggered terms has tended to see and portray the Senate as a neater, more coherent package than it actually was. The fact that the founders intended the Senate to be the less democratic chamber does not mean every feature of its composition, including staggered terms, must have been intended to contribute to that goal.

How Did Mere Description Become Constitutional Doctrine?

In light of the origins of Senate staggered terms, how and when did the idea of staggered elections as a form of rotation dissipate to be replaced, by and large, with an interpretation that conflated them with insulation, detachment, and continuity? When did the descriptive reality of continuity become a doctrine about Senate practice and procedure? That remains uncertain.

After ratification, some famous commentators, including St. George Tucker in 1803 and Joseph Story in 1833, still portrayed staggered terms as rotation.41 Nevertheless, at some point during these years—when and how remain a bit of a mystery—senators began developing and applying the doctrine of the Senate as a continuing body. That is, at some point senators took the mere fact of staggered elections and transformed it into a broader characterization of the Senate as a legislative body. It was no longer simply that staggered elections were one aspect of the Senate’s architecture, like equal representation or state selection. Instead, staggered elections made the Senate a continuing body, with certain constitutional attributes flowing from that status. And “continuing,” “permanent,” and “perpetual” all carried the implication of conservatism, in the literal sense, and insulation and detachment. In this way, the rise of the continuing body doctrine is inextricably linked to the interpretation of staggered elections as part and parcel of the Senate’s conservative purpose.

As indicated by this chapter’s epigraph, a quotation from Senator Buchanan, this understanding or claim goes back at least to 1841, and statements such as his imply that the concept was by that point a familiar one. What did Buchanan mean by asserting that the Senate “was emphatically a permanent body,” that there “could be no new Senate”? It was certainly more than a mere description based on the fact of staggered terms. Buchanan emphasized the three things that would remain the core of the continuing body doctrine down to the present. First was the general conservative consequence and purpose of continuity. In his words, the Senate “was the sheet-anchor of the Constitution, on account of its permanency.” Second, as the chief example of this continuity, the Senate’s “rules were permanent, and were not adopted from Congress to Congress, like those of the House of Representatives.” Finally, and as implied by the example of the rules, “one Senate” had the “right to bind its successors.”42 Notice that this last phrasing carries the linguistic and logical difficulty at the core of the doctrine: if it is always the same Senate, then how can one Senate be succeeded by another? And if it is the same Senate, why can’t it change its mind?

Subsequent debates in the Senate invoked 1841 as the first time the Senate considered, however briefly and inconsequentially, the meaning of its self-description.43 Coming as it did in the hotly partisan and sectional politics of the Jackson era, the debate in 1841 was hardly about the lofty and perpetual status of the Senate. And it was not about how Senate rules protect deliberation and minority rights, even though to that point, “the Senate had seen no more prolonged or partisan obstruction”44 than during this debate, which has been cited as the first unambiguous filibuster in Senate history.45 The matter at hand, and the object of the extended debate, was a raw and transparent partisan dispute about the Senate printer, of all things. For decades, nineteenth-century Congresses contracted private printers, typically publishers of partisan newspapers in Washington, D.C., to print public documents, including the proceedings of the House and Senate. The new majority party, the Whigs, started a special session of the new Twenty-Seventh Congress by moving to fire the printers recently hired by the outgoing Democratic majority at the end of the just expired Twenty-Sixth Congress. Filibuster or no, for several days the Democrats put up a fuss, two senators almost had a duel over their ad hominem remarks, and a few senators, as minor asides in their speeches, characterized the Senate as a continuing body.46

The details need not detain us except to note that, aside from the accusations of naked partisanship from both sides, the main points of dispute were about whether the Senate was acting in its legislative or executive capacity during this special session, whether the printer qualified as an officer of the Senate, and whether or in what way the contract reached with a printer could be terminated. Buchanan was the only senator to speak more than a few words in support of the continuing body concept, and it was at best a secondary argument. In fact, in the context of Buchanan’s full commentary, his invocation of the Senate as a continuing body was almost a non sequitur and somewhat absurd. As part of his argument that the printer hired during the Twenty-Sixth Congress could not be fired by the Senate of the Twenty-Seventh, Buchanan claimed, as noted, an unqualified right for the Senate at one point in time to bind itself and its successors because there is never a different or new Senate. It was a declaration rather than an argument, and a point, one suspected, he would find himself disputing if the partisan shoe had been on the other foot. One senator spoke in opposition to Buchanan’s characterization of what a “permanent body” implied, and two others referred to the Senate’s continuity in a single sentence, each amid much longer remarks focused on the other more pertinent arguments. The rest of the debate and the final outcome—Buchanan and the other Democrats lost—suggest the status of the Senate as a continuing body was irrelevant, ignored, and certainly far from settled.47

This pattern of brief and desultory invocations continued through the nineteenth century. Several times, especially in the 1870s and 1880s, it came up in discussions of the status of the Senate’s president pro tempore, and once in 1876 in regard to the joint rules that Congress once maintained.48 If one surveys the occasions from 1841 through the early 1900s when the Senate discussed—however briefly—its status as a continuing body, several things are apparent. There was no unanimity, and no small part of this disagreement was partisan. Some senators argued, for example, that the House was just as perpetual, for it is always ready to meet if necessary. As well, the advocates of the doctrine could never connect mere or descriptive continuity—that is, the fact that only one-third of the Senate is up for election every two years, or the ability of the Senate to meet at any time related to its executive functions—to the implied broader doctrine, that descriptive continuity determines how the Senate should or must conduct its business, such as continuing its rules from one Congress to the next. Instead, they often referred to Buchanan’s words in 1841 and—as Buchanan did—to unnamed authorities who all agreed that the Senate is the continuing body intended by the framers, who were then referenced imprecisely or not at all. For example, Senator Thomas Harkwick in 1917, whose “conviction on this subject was . . . profound,” knew that the Senate “was intended by the makers of our Constitution to be a permanent body, and provision was made that two-thirds of its membership should always be in office.”49 The straw of descriptive continuity was never turned into the gold of constitutional doctrine by any sort of logic that was not, in the end, a circular reference to staggered elections.

Despite the lack of rigor and logic, the continuing body doctrine endured for a variety of reasons, and it became a commonly invoked pillar of Senate identity, as indicated by the quotations from George Haynes, William White, and Senator Robert Byrd at the start of this chapter. It is not hard to see the reasons why. The doctrine is based on a stubborn and unchanging descriptive fact stemming from staggered elections. As well, push never had to come to shove about whether the doctrine was more than a convenient if imprecise set of assumptions. Finally, the doctrine is flattering as another coat of luster on the exceptional Senate, another alleged facet of its unique status in the Constitution and American system. The doctrine just lingered pretty much as Senator Buchanan had articulated it in 1841, available for use when and where convenient.

All of this suggests the following conjecture: Could it be that the Senate began to construct itself as a continuing body based on the fact of staggered terms, and, as the doctrine of a continuing body took hold, the functional purpose of and intent behind staggered terms evolved to harmonize with this new doctrine? That is, instead of a particular interpretation of the founding purpose of staggered terms driving the idea of a continuing body, could the subsequent appeal and utility of the continuing body doctrine have created an interpretation of the founders’ intent for this small but important feature of the Constitution? Senators developed a motivated bias for appealing and adhering to what became the conventional wisdom about staggered terms because it supported the attractive features of the continuing body doctrine. The Senate’s self-conception and definition as a continuing and deliberative body circled back to build and reinforce the conventional wisdom about staggered terms: that the Senate is a continuing body, which the framers must have intended, and so staggered terms must have been designed to produce that result.

This motivated bias suggests that two understandable but faulty forms of reasoning contributed to the rise and power of the conventional wisdom. The first is what one might call the fallacy of coherent construction. It is hardly novel to point out how frequently and misleadingly “the framers’ intent” is invoked, as though a particular facet of the Constitution were unambiguous in its construction or purpose. In some instances, such a generalization is not an abuse, but in most cases it is a distortion. And that is true of almost anything involving the Senate, which was, after all, the object of the Great Compromise that blended the oil of the Senate as the bastion of federalism with the water of the Senate as the citadel of far-sighted statesmen. Nevertheless, we tend to see and portray the Senate as a neater, more coherent package than it actually was.

The second is a version of the teleological fallacy, the familiar problem of reasoning from functional effects backward to intent and origins. Because X results in Y, X was designed to produce Y. Insofar as there is no purely functional reasoning in this instance—it has all been tainted by assumed knowledge of the founding—this fallacy rests primarily on observations about the impact of staggered terms on the Senate, especially compared to the House. As the Constitution was put into practice and concerns about long terms quickly disappeared amid a gradual process of democratization, the most obvious effect of staggered terms was the insulation of two-thirds of the Senate at every national election—rather than the opportunity to refresh one-third with new blood—even if the actual history of incumbency, turnover, and party control in each chamber complicated the impression of a volatile House and stable Senate. It also became commonplace to assume that all representatives were thinking about reelection on an ongoing basis, whereas only one-third of the Senate seemed so directly afflicted. As the average tenure of representatives and senators quickly converged, the difference in institutional knowledge and stability seemed less important than the difference in electoral cycles. These developments, along with a lack of scholarship on the origins of staggered terms specifically, facilitated the understandable conflation, by senators and scholars alike, that staggered elections with longer terms and selection by state legislatures were part of the founders’ conservative intentions.

I contend that just as the origins of staggered terms for the Senate are more complex and interesting than the conventional wisdom implies, the relationship between the interpretation of staggered terms and the development of the doctrine of the Senate as a continuing body has likely been an interdependent and mutually reinforcing discursive process. Regardless of the exact relationship of staggered terms to the continuing body doctrine, the result was a conventional interpretation based more on the consequences of staggered terms in practice and discourse than on their historical origins.

The Self-Serving Illogic of the Continuing Body Doctrine

Beyond the lack of constitutional foundation, the flaws in the logic of the continuing body as any sort of binding principle are numerous and compelling.50 And senators have been aware of them for at least a century. It is no coincidence that the longest discussion of whether or not the Senate is a continuing body in anything more than a descriptive sense came during the special Senate session in March 1917 that produced supermajority cloture. I analyze the creation of cloture in greater detail in the next chapter, but let me say here that after several episodes of unpopular filibusters and amid the rather sudden shift toward involvement in World War I, the Senate took up a proposal to add a procedure to its rules that would end debate with a vote by a supermajority of two-thirds of senators voting. As part of these proceedings, two senators, Robert Owen of Oklahoma and Montana’s Thomas Walsh, both of whom favored cloture reform, initiated the argument that the Senate is not a continuing body except for executive business. They did so in hopes of preventing a filibuster against the pending proposal to create the rule allowing debate to be terminated by a supermajority vote. On March 7, Senator Walsh took the floor and consumed the entire day subjecting the continuing body doctrine to a withering interrogation. Walsh was out to destroy the assumption that Senate rules continued from one Congress to the next. As Walsh had pointed out the day before, “The question as to whether the rules live from one Congress to the next has never been directly considered by this body, although many times incidentally it has been asserted that the Senate is a continuing body.”51 To Walsh, those assertions amounted to nothing more than the simple fact that “two-thirds of its Members remain in office at the expiration of each two-year period.”52 The Montana Democrat enumerated and explained the several problems and inconsistencies in the doctrine of the continuing body, including the paramount fact that all legislation dies at the end of a Congress. What stronger evidence could there be against the claim that the Senate is a continuing body than its own decision that its most important business, legislation, does not carry over from one Congress to the next? It if were, a bill reported by a Senate committee in an election year would still be alive for floor debate when the new Senate convened in the new year. And even if the putatively perpetual Senate passes a measure, but the House disapproves or even fails to take any action, both chambers must start over during the next Congress. This is parliamentary tradition rather than a provision in the Constitution or House and Senate rules. And yet it has never been questioned, particularly—and most tellingly—by any senator wielding the continuing body doctrine. The logic of this practice is self-evident. In his 1951 testimony before the Senate Rules Committee, Walter Reuther explained it this way: “The reintroduction of bills into the Senate of each new Congress is made necessary, of course, because a majority in favor or against a given bill may be changed by the election of new Senators to some or all of the one-third of the seats whose terms expire. A bill passed by an earlier Senate could not, therefore, be considered the will of the later Senate unless a new vote were taken.”53 With this and other examples, Walsh showed that the Senate decides when aspects of its business and organization continue from one Congress to the next; this is not determined by the consequences of staggered elections.54

Senator Walsh’s arguments, and others I will discuss, are as good today as they were over one hundred years ago. As he implied, the conception of the Senate as a continuing body might be more compelling were it not for the fact that the Senate itself is utterly inconsistent in its application of the principle. That is, the most important elements of what the Senate actually does—its business in its legislative and executive capacities—do not carry over, or continue, from one Congress into the next. Senator Walter Mondale made this clear during a 1975 debate on the filibuster and cloture reform. Mondale noted that during the various debates about cloture, “much has been said about the Senate being a ‘continuing’ body.” However, “The Senate is hardly a continuing body when it wipes the slate clean of bills, resolutions, nominations, and treaties at the beginning of each new Congress. Nor is it a continuing body with respect to many of its other actions.”55 Most of the key examples Mondale cited are not, like the idea of the continuing body, mere tradition or norms. They are in the Senate rules, the same rules that continue from Congress to Congress. Nominations do not even survive beyond a single session of a given two-year Congress.56 The memberships of Senate committees are appointed at the start of every Congress.57 Rule XXX specifies that “all proceedings on treaties shall terminate with the Congress, and they shall be resumed at the commencement of the next Congress as if no proceedings had previously been had thereon.” Treaties are not legislation requiring bicameral action. They are a shared power with the executive. As such, and as international agreements reached by the president, it would be logical for consideration of treaties to be carried over from one Congress to the next, even if the Senate were not a continuing body. Notice, however, that should the Senate decide to act on a treaty that was carried over from the last Congress, senators start from a clean slate, as if the president had been obliged to resubmit it.

As a result, the arguments for the continuing body doctrine frequently have had a circular quality. The Senate chooses to behave in a certain way because it is convenient or practical, such as having the president pro tempore serve until changed (that is, serving from one Congress to the next but at the pleasure of the Senate). Such things are clearly a choice, not a mandate determined by continuity. That behavior creates some continuity in Senate action across Congresses. The behavior is then justified by reference to the fact that it is a continuing body. But it is a continuing body because it chose, in this particular instance, to create a behavior that can be characterized as continuation. Other things do not “continue,” because the Senate chose not to behave that way. The body does not have to continue its rules from Congress to Congress; it chose to, and then chose to apply supermajority protections to those rules, which in turn were rationalized by the continuing body doctrine. In short, there was no clear theory of continuation that empowered or required particular behaviors with regard to the rules, committees, treaties, the president pro tempore, or anything else. Instead, chosen behaviors served as the proof that the Senate was the continuing body implied by staggered elections.

This circularity, where arguments about continuity chase their own tail, can be seen when supporters of the doctrine invoke a Supreme Court decision that briefly mentions the differences in continuity between the Senate and the House.58 The language in the decision did not amount to more than taking judicial notice of something as a fact, a fact that was, in any event, not central to the decision at hand. McGrain v. Daugherty, a 1927 decision, was about Congress’s power to compel witnesses to appear and testify as part of its constitutional duties.59 At the end of the decision, the Court, in discussing a secondary question, noted that the Senate was a continuing body, mostly because it has behaved that way. The decision pointed out that the Senate had at times specified that the work of committees could extend beyond the end of a Congress, in the interim before the new Congress commences.60 That is the full extent of the Court’s recognition of the Senate as a continuing body. Voilà: the continuing body doctrine has constitutional sanction because the Supreme Court has taken judicial notice of the fact that the Senate chooses to behave, in certain instances, like a continuing body. The Senate can choose to behave in some ways because of staggered terms—such as allowing committees to exist or function between Congresses—that make it continuing in practice by its actions rather than by mere description. Staggered terms, however, do not compel the Senate to turn description into action; they do not determine anything beyond how elections affect the membership of the Senate.

The list of important ways in which the Senate does not act according to the putative logic of a continuing body demonstrates, as Aaron-Andrew Bruhl puts it, that “the exception is, of course, the Senate’s rules. What we have then is not so much a bunch of data points scattered all over the place but rather a line with an anomalous outlier representing the Senate’s handling of its own rules.”61 The Senate has used the continuing body doctrine to protect its rules and little else. And, as if to give final proof of this, a particular group of senators with a singular stake in protecting the rules that gave them leverage against an emerging civil rights movement got the continuing body doctrine written into those same Senate rules.

From Doctrine to Rule: The Continuing Body Doctrine Gets Codified in Service of White Supremacy

For many decades this protection of the rules was not, as mentioned, a Senate rule but a tradition or practice justified by the continuing body doctrine. But even this telling exception to protect the rules makes no sense. Just because in theory there might be two-thirds returning senators and one-third new senators, why does that preclude majority action on a new set of rules? Even with addition of the one-third, there could easily be a new majority, as far as sentiment concerning the rules, within the new Senate. And as Walter Reuther argued as part of his 1951 testimony, this new group of senators “must be able to express its will on the rules,” particularly something as important as the rule on cloture because of its potential effect on the Senate’s ability to consider and decide on the substantive legislation that has to be introduced each Congress.62

In 1959, however, the Senate made sure that such a majority would never be able to upset tradition and attempt a majority vote on the rules, and, as with so much else about the Senate throughout its history, this action was directly connected to southern senators’ attempts to protect white supremacy in their states and region.

That year Rule V was amended to include the following: “The rules of the Senate shall continue from one Congress to the next Congress unless they are changed as provided in these rules”63—meaning that a two-thirds supermajority would be required to shut off debate on any proposal to change the rules; a new Senate would not be afforded the opportunity to change the rules by a simple majority. Prior to Rule V, section 2, nothing in the Senate rules embodied or even implied anything about the Senate’s undying nature or what it might entail for its rules. This change inscribed for the first time in Senate rules what had heretofore been only a tradition and codified what some senators took to be the principal implication of the Senate as a continuing body. However, Rule V was not written primarily to enshrine a principle of Senate continuity; it was written to protect the filibuster from future threats. The revised language of Rule V was introduced and passed as part of an attempt to protect supermajority cloture from substantial reform by drawing on and codifying the continuing body doctrine in service of southern resistance to civil rights.

Senate obstruction or filibusters of civil rights measures in the postwar era was meeting increased opposition in the late 1950s in the wake of the 1954 Brown decision and an increasingly liberal Senate majority. Some northern Republican and Democratic senators were pushing for reform of Rule XXII, the cloture rule that empowered filibusters by requiring a two-thirds vote of all senators to end debate. Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson sought a compromise that would placate both reformers and the southern Democrats. Johnson’s compromise lowered the cloture threshold from two-thirds of all members to two-thirds of those present, and it provided that cloture could be applied to any motion to proceed to consideration of a change in the rules. This was hardly major reform. But to smooth the path to this all but meaningless change by offering further protection to southern Democrats, Johnson added the language that altered Rule V to codify that the rules continued from one Congress to the next. The Rule V language was sought particularly by Richard Russell, leader of the southern Democrats seeking first, last, and always to preserve their ability to filibuster any and all civil rights legislation. The amendment of Rule V was not a means to the end of protecting the filibuster as a matter of principle, it was another concession to racist southern senators seeking to protect their power to obstruct or prevent even the most limited efforts by Congress to protect the rights of African Americans.64 This divided advocates of reform by confronting them with a no-win choice: go for mild filibuster reform to show change is possible but with it get a provision that would all but preclude future rule changes, or kill reform to stave off the enshrinement of the continuing body myth (again, applied only to Senate rules, not to other aspects of its business). But in the end, the compromise passed easily.65 By combing the two-thirds threshold with Rule V’s explicit mandate that the rules continue unless changed against the extraordinary odds set by Rule XXII, the Senate entrenched cloture from alteration by even substantial supermajorities.

As the means to this end, the revised Rule V became the most prominent and powerful acknowledgment of the circularity of the continuing body doctrine and its relationship to the Senate’s tortured contrast between its lofty self-conceptions and the ugly politics those conceits attempted to obscure. As the 1959 reform debate drew to a close, Majority Leader Johnson was summing up what the compromise agreement would accomplish. “This resolution,” Johnson concluded, “would write into the rules a simple statement affirming what seems no longer to be at issue. Namely, that the rules of the Senate shall continue in force, at all times, except as amended by the Senate. This preserves indisputably the character of the Senate as the one continuing body in our policy-making process.”66 Once again, as Johnson’s words unintentionally confirmed, the Senate is a continuing body insofar as it chooses to behave like one for certain defined purposes and because it structures its rules accordingly, not because the Constitution made it so or obliges the Senate to act one way or another owing to staggered elections.

House and Senate Elections: Not So Different after All

But is the Senate different from the House as a result of those staggered elections? Whether or not the Senate is a continuing body in any more than descriptive terms, its membership is determined in part by its staggered six-year terms relative to the two-year terms for the House. What I have not considered to this point is whether this constitutional distinction has made a difference as far as membership and behavior are concerned, distinct from the debate about its status as a continuing body. Some aspects of this puzzle are complicated or unanswerable. I will address briefly the question most relevant to the concerns of this chapter: whether or not staggered terms produce a more stable Senate membership compared to the House. No doubt some founders recognized the buffering effect staggered elections could have, in theory, and it is fair to view them as a potential barrier to rapid change. But the historical record of the buffer in action is less neat. For one thing, for the first 125 years of its existence, the Senate was picked not by “voters” but by state legislatures. Election by state legislature was the constitutional safeguard for picking the Senate. House elections in the nineteenth century tended to be more volatile, but the relative contributions of staggered elections versus selection by state legislature would have to be disentangled, even if one suspects that staggered elections mattered quite a bit.67

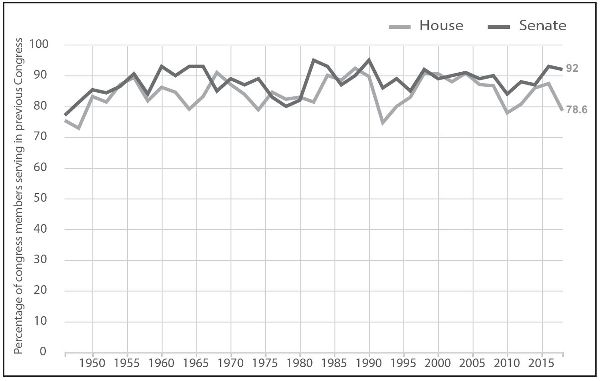

Regardless, after senators became directly elected, House and Senate elections came to display some remarkable and persistent similarities that from an empirical perspective make the idea of the Senate as a continuing body look rather academic or abstract. For example, from 1946 through 2014 (a total of thirty-five elections), following a presidential or midterm election, an average of 87.8 percent of the Senate had served in the previous Congress (figure 5). While this sounds like an impressive level of continuity—arguably the kind of continuity that could be credited to staggered elections—the House has averaged nearly the same level of continuity despite all 435 seats being contested every election. Over the same period, an average of 84.4 percent of every new House consisted of members from the previous Congress, remarkably close to the Senate average of nearly 88 percent. Not infrequently an incoming House has been more “continuing” than the postelection Senate that same year. Eight of the thirty-five elections from 1946 to 2014 produced Congresses with a greater percentage of continuing representatives than senators, and two were all but ties.68 As others have shown, in modern elections Senate incumbents have been, on average, more vulnerable than House incumbents.69 If the counterfactual alternative is simultaneous six-year Senate terms, there is little doubt—assuming the same pattern of incumbency and congressional careers—that staggered elections increase change and dynamism rather than stability.

Fig. 5. Continuity of Senate and House membership, 1946–2018

Data: Brookings Institution, Vital Statistics on Congress: Data on the U.S. Congress, updated February 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/multi-chapter-report/vital-statistics-on-congress/.

Moreover, staggered elections aside, it is not clear that even the six-year term makes much of a difference in the relative behavior of senators and representatives. As I have shown, staggered terms were about rotation and change within the context of the longer term, which was the intended source of stability and conservatism. That is, if staggered elections do not result in a more stable membership in the Senate than in the House, then any behavioral differences can be attributed largely to the longer term. Political scientists have done some work on the impact of two- versus six-year terms. For example, do the one-third of senators who are up for election behave differently from the two-thirds who are not? The findings are, at best, ambiguous.70 Effects are elusive, limited, and probably of a diminished nature in the contemporary era of the perpetual campaign, ceaseless fundraising, the 24/7 news cycle, and social media. In an atmosphere of hyperpartisanship, partisan sorting, and highly engineered districting, the partisan complexion of the state or district probably makes more difference than the electoral cycle of two- or six-year terms.

This brief dip into the empirical reality of bicameral elections and behavior cannot undermine the continuing body doctrine, which is based on the mere fact of staggered elections, regardless of their actual effects. But the historical pattern of House and Senate electoral outcomes shows that the concept, in addition to being institutionally incoherent, has almost no practical meaning.

The Undying Body, or The Rights of the Living Dead

The irony is that staggered elections, a category of rotation intended to prevent the entrenchment or perpetuation of institutional power, produced instead the notion of an undying Senate, and are interpreted as a vital part of the Senate’s conservative purpose. Senators and scholars alike will no doubt continue to debate the constitutional and institutional status of the doctrine. Let me reiterate my findings: staggered terms were for institutional accountability, not institutional entrenchment. The doctrine took a constitutional stipulation about the composition of the Senate—how it is elected—and turned it into a rule about the status and operation of the Senate, at least for the few things the Senate chooses. Again, whatever the exact mixture of motives and rationales for staggered elections, the irony is that this produced the notion of an undying Senate and is interpreted, against the grain of the records of the founding and modern electoral history, as a vital part of the Senate’s conservative purpose. For the Senate to entrench its decisions, to protect them from the preferences of a new Senate majority, is the opposite of the main intention behind staggered terms, even if that original purpose might not deter senators’ desire to apply this particular self-conception.

In fact, the continuing body doctrine takes the Senate beyond the worst fears of rotation’s advocates insofar as it entrenches not simply the power of current members but also the decisions of those who are no longer in office, a majority that no longer exists.71 As a result, the new majority—something that rotation was intended to produce—is effectively anchored to the past. Anchored to the decisions, in many cases, of the long dead and departed. Senator Thomas Walsh, as part of his all-day speech in 1917 excoriating the continuing body doctrine, lamented the Senate’s reification of its rules. Walsh took a moment to both acknowledge the general wisdom of his predecessors yet poke a bit of fun at the rigidity of the Senate’s adherence to the past. Quoting Lord Byron, Walsh noted of ancestral senators “that we are required . . . to salute them as: ‘The dead but sceptered sovereigns, who still rule our spirits from their urns.’”72

It is also a case in point that the supposed Senate principle of “minority” voice or rights grates loudly against the continuing body claim. After all, if minorities have special rights or protections in the Senate, then how is it that the approximate one-third of “new” senators after any election can be denied a say in the rules by a purely hypothetical majority of the two-thirds who constitute the continuing Senate after any election? Moreover, it is not clear that the continuing two-thirds have any special status since they probably never had the opportunity to vote on the things that are being protected by the Senate’s being a continuing body. Most of that continuing two-thirds were at one time in the not very distant past, as individuals, part of the new one-third. In short, what I have called descriptive or mere continuity—the continuity structured by staggered elections—is really “temporary” or “transient” continuity, and any continuity beyond that in process or action is a matter of Senate choice, based on a particular political theology.

The continuing body is there to protect the decision of a majority or supermajority that no longer exists and may not have for generations. And thanks to Rule V, the minority (or majority) might not even have the chance to debate, let alone change, the decision from long ago. Isn’t it a particular egregious violation of rights, minority or otherwise, to be silenced or stymied, not by the living but by the dead?

Not if you are Senator David Turpie. In 1893, Turpie, an Indiana Democrat, used the continuing body notion to take the argument about Senate rules one step closer to the Constitution. “Is not the Constitution of the United States the will of the majority,” asked Turpie during a debate over a proposed cloture rule, “a will of the majority, permanent, enduring; a law for all generations? Are not the rules of the Senate of the United States, most of them a hundred years old, the will of the majority, the permanent will?”73 Senate rules become a form of higher law simply by their rigged or enforced endurance, the living legacy of the long departed. And no such legacy has had a more exalted status or more impact—especially on the fate of civil rights—than Senate Rule XXII, the provision that required, prior to 2013, a supermajority to close debate on any matter before the Senate.