Avoidant Personality Disorder and its Relationship to Social Anxiety Disorder

Abstract

This chapter is a review of the empirical literature on the relationship of avoidant personality disorder (APD) and social anxiety disorder (SAD). Research reviewed included comorbidity, longitudinal treatment outcome, statistical analysis of social anxiety symptoms in large populations and genetic findings. APD is found to be an internally consistent personality disorder that can be reliably measured. APD causes morbidity through interfering with social interactions and may affect such important life parameters as dating, marriage, friendship and employment. APD is also relatively common in general and clinical populations. This prevalence and morbidity make it an appropriate focus of clinical treatment. APD and SAD share symptoms (differing only in severity), are responsive to the same pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions and seem to be identical genetically. The best conceptualization is that SAD is a milder variant of APD and that they are the same disease. The DSM diagnoses of SAD and APD have gradually moved closer together and currently there are no specific distinguishing features of the two disorders found.

Keywords

Introduction

Diagnostic issues using the DSM

Table 2.1

DSM criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder and for Avoidant Personality Disorder

| Social Anxiety Disorder | Avoidant Personality Disorder | |

| DSM-III criteria | A persistent, irrational fear of and compelling desire to avoid, a situation in which the individual is exposed to possible scrutiny by others and fears that he or she may act in a way that will be humiliating or embarrassing. Causes significant distress. Not due to Avoidant Personality Disorder or other mental disorder. | Hypersensitivity to rejection. Unwillingness to enter into relationships. Social withdrawal. Desire for affection and acceptance. Low self esteem. |

| DSM-III-R criteria | A persistent fear of one or more social phobic situations in which the person is exposed to possible scrutiny by others and fears that he or she may do something or act in a way that will be humiliating or embarrassing. Unrelated to other Axis I or III disorders. Exposure to phobic stimulus causes anxiety response. Situation is avoided or endured with anxiety. Causes occupational or social dysfunction or subjective distress. May be generalized. | A pervasive pattern of social discomfort, fear of negative evaluation and timidity, beginning in early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts as indicated by four of the following: easily hurt by criticism; no close friends; unwilling to get involved with people; avoids activities with significant interpersonal contact; reticent in social situations; fears being embarrassed; exaggerates potential difficulties. |

| DSM-IV criteria | A marked and persistent fear of one or more social or performance situations. Exposure to feared social situation invariably provokes anxiety. Feared situations are avoided or endured with distress. Significant occupational or social dysfunction. May be generalized. | A persistent pattern of social inhibition, feelings of inadequacy, and hypersensitivity to negative evaluation as indicated by four of the following: avoids activities involving significant interpersonal contact; unwilling to get involved with people; shows restraint in intimate relationships; preoccupied with being criticized or rejected; inhibited in new interpersonal situations; views self as socially inept, unappealing or inferior; is unusually reluctant to take personal risks. |

| DSM-5 criteria | Fear or anxiety related to one or more social situations. Patient fears that their acts or anxiety will result in humiliation, embarrassment or rejection by others. Social situations almost always provoke fear or anxiety. The fear is out of proportion to the actual threat. Minimum duration six months. The only subtype is “performance” which is restricted to speaking or performing in public. | Unchanged from DSM-IV. |

Review of early findings

Studies comparing SAD to APD

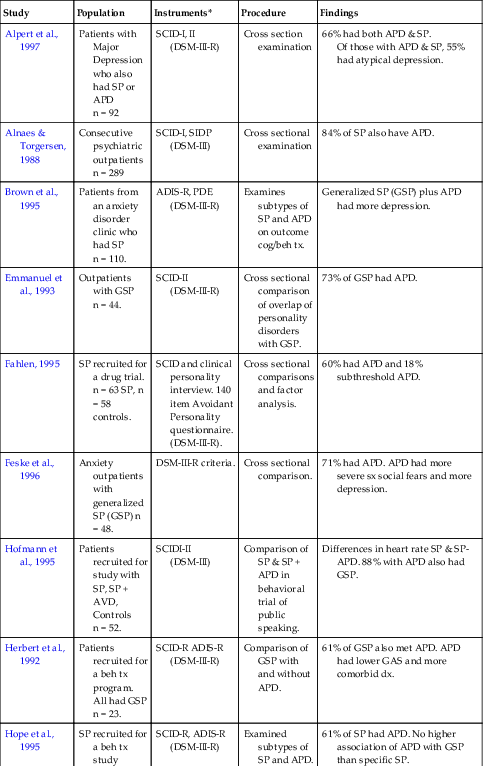

Table 2.2

Earlier studies comparing Social Phobia (SP) to Avoidant Personality Disorder (APD)

| Study | Population | Instruments* | Procedure | Findings |

| Alpert et al., 1997 | Patients with Major Depression who also had SP or APD n = 92 | SCID-I, II (DSM-III-R) | Cross section examination | 66% had both APD & SP. Of those with APD & SP, 55% had atypical depression. |

| Alnaes & Torgersen, 1988 | Consecutive psychiatric outpatients n = 289 | SCID-I, SIDP (DSM-III) | Cross sectional examination | 84% of SP also have APD. |

| Brown et al., 1995 | Patients from an anxiety disorder clinic who had SP n = 110. | ADIS-R, PDE (DSM-III-R) | Examines subtypes of SP and APD on outcome cog/beh tx. | Generalized SP (GSP) plus APD had more depression. |

| Emmanuel et al., 1993 | Outpatients with GSP n = 44. | SCID-II (DSM-III-R) | Cross sectional comparison of overlap of personality disorders with GSP. | 73% of GSP had APD. |

| Fahlen, 1995 | SP recruited for a drug trial. n = 63 SP, n = 58 controls. | SCID and clinical personality interview. 140 item Avoidant Personality questionnaire. (DSM-III-R). | Cross sectional comparisons and factor analysis. | 60% had APD and 18% subthreshold APD. |

| Feske et al., 1996 | Anxiety outpatients with generalized SP (GSP) n = 48. | DSM-III-R criteria. | Cross sectional comparison. | 71% had APD. APD had more severe sx social fears and more depression. |

| Hofmann et al., 1995 | Patients recruited for study with SP, SP + AVD, Controls n = 52. | SCIDI-II (DSM-III) | Comparison of SP & SP + APD in behavioral trial of public speaking. | Differences in heart rate SP & SP-APD. 88% with APD also had GSP. |

| Herbert et al., 1992 | Patients recruited for a beh tx program. All had GSP n = 23. | SCID-R ADIS-R (DSM-III-R) | Comparison of GSP with and without APD. | 61% of GSP also met APD. APD had lower GAS and more comorbid dx. |

| Hope et al., 1995 | SP recruited for a beh tx study n = 23. | SCID-R, ADIS-R (DSM-III-R) | Examined subtypes of SP and APD. | 61% of SP had APD. No higher association of APD with GSP than specific SP. |

| Holt et al., 1992 | Patients recruited from an anxiety disorders clinic n = 30. | ADIS-R PDE (DSM-III-R) | GSP with and without APD and SP without APD compared. | APD appears to just identify a slightly more severe type of GSP. |

| Jansen et al., 1994 | Patients from a Netherlands outpatient psych clinic n = 117. | Axis I clinical interview, Axis II SCID-II (DSM-III-R). | Panic vs SP for personality variables. | Fear of being embarrassed discriminated best between Panic and SP. 31% of SP had APD. |

| Mersch et al., 1995 | Patients recruited by Swedish newspaper for SP tx study n = 34. | Axis I, clinical interview Axis II, SCID-II (DSM-III-R). | SP with and without personality disorder. | 23% had APD. Those with APD were somewhat more disabled. |

| Noyes et al., 1995 | Panic and SP patients recruited from news media. SP n = 46. | SICD (DSM-III-R), PDQ (DSM-III) | Examines personality traits in Panic and SP. | GSP had 50% more personality traits from the anxious and schizoid clusters than SP. |

| Reich et al., 1989 | SP outpatients n = 14. | Axis I, SCID-I, SCID-II (DSM-III-R). | Pharm tx study | 50% of SP also had APD. |

| Sanderson et al., 1994 | SP, GSP outpatients n = 51. | SCID-II (DSM-III-R). | Cross sectional comparison. | 61% had a personality disorder and 37% had APD. |

| Schneier et al., 1991 | SP drawn from an anxiety disorders clinic n = 50. | Axis I, semi-structured interview Axis II, SCID-II (DSM-III-R). | Comparison of subtypes of SP and relationship to APD. | APD in discrete SP = 21%. APD in GSP = 89%. |

| Tran and Chambless, 1995 | Outpatients with a primary dx of SP n = 45. | Axis I, SCID (DSM-III-R) Axis II, MCMI or MCMI-II. | Comparison of subtypes of SP. | GSP more socially disabled than SP. APD-GSP had more depression than GSP. |

| Turner et al., 1991 | Outpatients SP, GSP = 71. | SCID (DSMII-R). | Cross sectional, association with personality disorders. | 37% had a personality disorder, 22% prevalence of APD. |

| Turner et al., 1992 | SP from an anxiety disorder clinic n = 89. | ADIS-R, SCID-II (DSM-III-R). | Comparison of specific SP, GSP and APD. | GSP is more similar than different from APD, differing on only one of four dimensions (social anxiety). There was no difference in social skills between GSP and APD. |

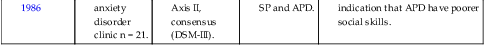

| Turner et al., 1986 | SP from an anxiety disorder clinic n = 21. | Axis I, ADIS Axis II, consensus (DSM-III). | Comparison of SP and APD. | GAS and SP very similar, but indication that APD have poorer social skills. |

PDE = Personality Disorder Examination (Loranger et al., Cornell University)

SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (Spitzer et al., New York State Psychiatric Institute)

ADIS-R = Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule—Revised (Barlow et al., Boston University)

The association of SAD to other Personality Disorders

Treatment and outcome studies for SAD and APD

Psychopharmacological treatment studies

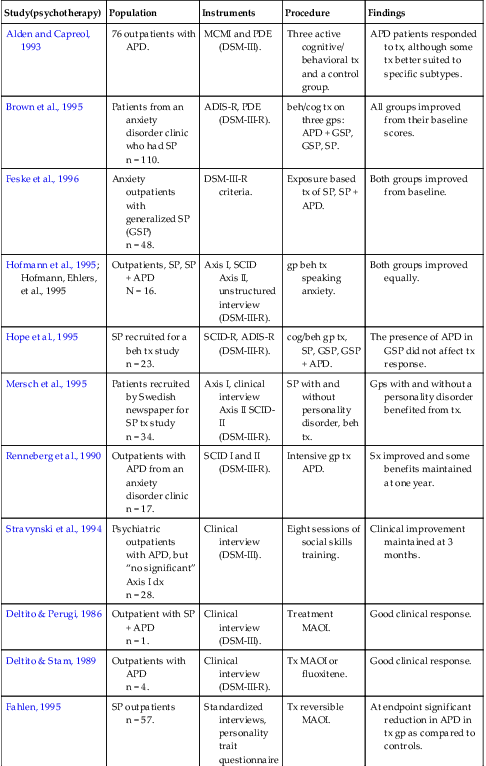

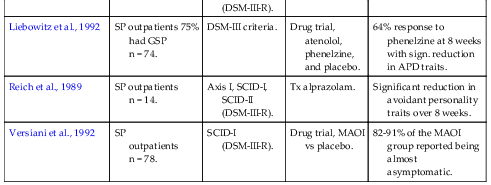

Table 2.3

Earlier treatment studies of Social Phobia (SP) and Avoidant Personality Disorder (APD)

| Study(psychotherapy) | Population | Instruments | Procedure | Findings |

| Alden and Capreol, 1993 | 76 outpatients with APD. | MCMI and PDE (DSM-III). | Three active cognitive/ behavioral tx and a control group. | APD patients responded to tx, although some tx better suited to specific subtypes. |

| Brown et al., 1995 | Patients from an anxiety disorder clinic who had SP n = 110. | ADIS-R, PDE (DSM-III-R). | beh/cog tx on three gps: APD + GSP, GSP, SP. | All groups improved from their baseline scores. |

| Feske et al., 1996 | Anxiety outpatients with generalized SP (GSP) n = 48. | DSM-III-R criteria. | Exposure based tx of SP, SP + APD. | Both groups improved from baseline. |

| Hofmann et al., 1995; Hofmann, Ehlers, et al., 1995 | Outpatients, SP, SP + APD N = 16. | Axis I, SCID Axis II, unstructured interview (DSM-III-R). | gp beh tx speaking anxiety. | Both groups improved equally. |

| Hope et al., 1995 | SP recruited for a beh tx study n = 23. | SCID-R, ADIS-R (DSM-III-R). | cog/beh gp tx, SP, GSP, GSP + APD. | The presence of APD in GSP did not affect tx response. |

| Mersch et al., 1995 | Patients recruited by Swedish newspaper for SP tx study n = 34. | Axis I, clinical interview Axis II SCID-II (DSM-III-R). | SP with and without personality disorder, beh tx. | Gps with and without a personality disorder benefited from tx. |

| Renneberg et al., 1990 | Outpatients with APD from an anxiety disorder clinic n = 17. | SCID I and II (DSM-III-R). | Intensive gp tx APD. | Sx improved and some benefits maintained at one year. |

| Stravynski et al., 1994 | Psychiatric outpatients with APD, but “no significant” Axis I dx n = 28. | Clinical interview (DSM-III). | Eight sessions of social skills training. | Clinical improvement maintained at 3 months. |

| Deltito & Perugi, 1986 | Outpatient with SP + APD n = 1. | Clinical interview (DSM-III). | Treatment MAOI. | Good clinical response. |

| Deltito & Stam, 1989 | Outpatients with APD n = 4. | Clinical interview (DSM-III-R). | Tx MAOI or fluoxitene. | Good clinical response. |

| Fahlen, 1995 | SP outpatients n = 57. | Standardized interviews, personality trait questionnaire (DSM-III-R). | Tx reversible MAOI. | At endpoint significant reduction in APD in tx gp as compared to controls. |

| Liebowitz et al., 1992 | SP outpatients 75% had GSP n = 74. | DSM-III criteria. | Drug trial, atenolol, phenelzine, and placebo. | 64% response to phenelzine at 8 weeks with sign. reduction in APD traits. |

| Reich et al., 1989 | SP outpatients n = 14. | Axis I, SCID-I, SCID-II (DSM-III-R). | Tx alprazolam. | Significant reduction in avoidant personality traits over 8 weeks. |

| Versiani et al., 1992 | SP outpatients n = 78. | SCID-I (DSM-III-R). | Drug trial, MAOI vs placebo. | 82-91% of the MAOI group reported being almost asymptomatic. |