Chapter 24

A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of Social Anxiety Disorder

Richard G. Heimberg1

Faith A. Brozovich2

Ronald M. Rapee3

1 Adult Anxiety Clinic/Department of Psychology, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA2 Department of Psychology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA

3 Centre for Emotional Health/Department of Psychology, Macquarie University, Australia

Abstract

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is one of the most common and impairing psychological disorders. To advance our understanding of SAD, several researchers have put forth explanatory models over the years, including one which we originally published almost two decades ago (Rapee & Heimberg, 1997), which delineated the processes by which socially anxious individuals are affected by their fear of evaluation in social situations. Our model, as revised in the 2010 edition of this text, is summarized and further updated based on recent research on the multiple processes involved in the maintenance of SAD.

Keywords

social anxiety disorder

social phobia

anxiety disorder

anxiety

cognitive-behavioral model

Social anxiety disorder is characterized by an intense fear of being negatively evaluated by others in social situations, according to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Since it was first recognized as a mental disorder in DSM-III (APA, 1980), its prevalence (Kessler, Berglund et al., 2005; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005), chronicity (Bruce et al., 2005; Chartier, Hazen, & Stein, 1998; Reich, Goldenberg, Vasile, Goisman, & Keller, 1994), and associated personal, economic, and societal costs (Acarturk, de Graaf, van Straten, ten Have, & Cuijpers, 2008; Acarturk, Smit, et al., 2009; Aderka et al., 2012; Rodebaugh 2009; Safren, Heimberg, Brown, & Holle, 1997; Schneier, Johnson, Hornig, Liebowitz, & Weissman, 1992; Schneier et al., 1994; Tolman et al. 2009; Whisman, Sheldon, & Goering, 2000), as well as comorbidity with other disorders (Magee, Eaton, Wittchen, McGonagle, & Kessler, 1996; Ruscio et al., 2008), have been well documented. To move our understanding of the nature and treatment of social anxiety disorder forward, several researchers have proposed explanatory models, dating back to the early work of Schlenker and Leary (1982). The most widely cited and applied of these models have been those of Clark and Wells (1995; see also Clark, 2001) and Rapee and Heimberg (1997; updated by Heimberg, Brozovich, & Rapee, 2010), although other fruitful models have also been proposed (e.g., Hofmann, 2007; Kimbrel, 2008; Moscovitch 2009; see J. Wong, Gordon, & Heimberg, in press, for a comparative review of these models). In this chapter, we focus on our cognitive-behavioral model for social anxiety disorder, which delineates the processes by which socially anxious individuals are affected by their fear of evaluation in social situations.

The original model provided a solid framework for understanding the factors that comprise and maintain social anxiety disorder. Since the publication of Rapee and Heimberg (1997), we have conducted reviews of the literature that support various aspects of the model (Roth & Heimberg, 2001; Turk, Lerner, Heimberg, & Rapee, 2001), applied the model to a case study of a person with social anxiety disorder (Heimberg, Rapee, & Turk, 2002), and conducted a comparison between our model and the model proposed by Clark and Wells (Schultz & Heimberg, 2008; J. Wong et al., in press). Given that there had been several years of intervening research since the publication of Rapee and Heimberg (1997), we presented an initial integration of several additional variables into the model (Heimberg et al., 2010). That effort focused primarily on the important role of imagery, post-event processing, fear of positive evaluation, and the potential role of difficulties in the regulation of emotional responses, including but not limited to anxiety, as well as the combined cognitive biases hypothesis (Hirsch, Clark, & Mathews, 2006). In this chapter, we present a summary of the model as modified by Heimberg et al. (2010), with further adjustments as suggested by recent research. Research support for most previously presented aspects of our model appears in other papers cited above.

The model

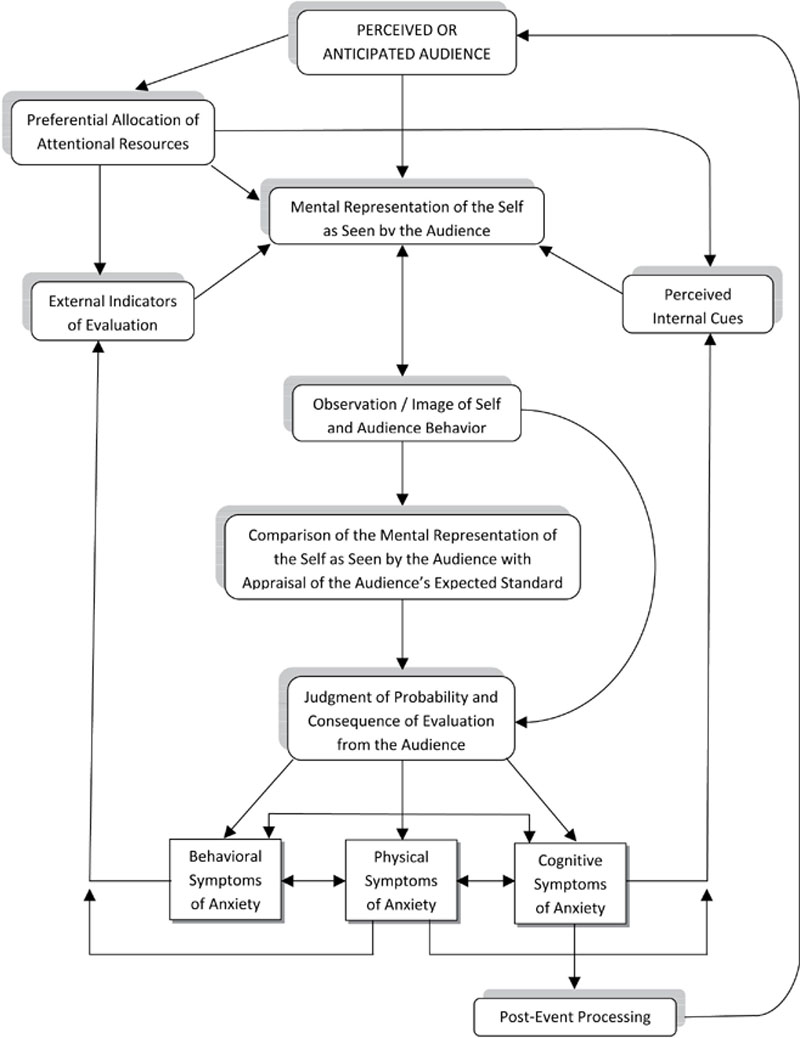

The model (see Figure 24.1

) attempts to explain the generation and maintenance of anxiety in affected persons upon entry into or anticipation of a social situation. We define social situations broadly, suggesting that a perceived or anticipated audience constitutes a significant threat. When these situations are encountered or anticipated, individuals with social anxiety disorder experience fear because they assume that others are naturally critical and, therefore, evaluation will be forthcoming. Individuals with social anxiety disorder also consider being liked and regarded with high esteem as fundamentally important, which heightens the potency of this evaluative threat. In the presence of threat (i.e., after the detection of an audience), socially anxious individuals become increasingly vigilant for cues that would signal the realization of their feared outcomes, and they attend to several sources for possible information on the proximity of these outcomes, including environmental cues, a mental representation of how they believe they appear to others, and cognitive, behavioral, and affective cues related to the severity of their anxiety in the moment.

Figure 24.1

A Cognitive Behavioral Model of Social Anxiety Disorder.

Perceived or Anticipated Audience

For socially anxious individuals, the social situation begins with the perception that they have an audience. The perceived audience includes not only the members of the audience when one is giving a formal public speech or a person who conducts an evaluative job interview but may also include others with whom the individual interacts in dating or casual social interactions, or even those individuals who could pose a seemingly more distant potential threat that the person might be evaluated. Thus, someone walking down the street who might view the socially anxious person and think poorly of how he or she looks, a person sitting on a facing bench when waiting for a train, or a person seated at another table at a restaurant may (unwittingly) become the perceived audience in the mind of the socially anxious individual. Characteristics of the audience (e.g., importance, attractiveness, age) as well as features of the situation (e.g., degree of anonymity of the socially anxious individual) influence the likelihood that the person’s schema of the perceived audience will be activated. This, in turn, impacts the level of anxiety initially experienced by the individual.

The perceived audience need not be physically present to ignite the processes described in the model. Socially anxious persons engage in significant anticipatory processing while anxiously awaiting social situations; that is, they think about situations to come and how these situations may turn out. We have much to learn about the nature of anticipatory processing in persons with social anxiety disorder, and it is likely that there are several aspects to it, including recalling similar past situations, worrying about the potential consequences of acting poorly or appearing nervous, and preparing in advance what one might say, among others. Clinical experience suggests that there is little good to come of this type of perseverative thinking. In fact, research has shown that, when socially anxious individuals engage in anticipatory processing, they experience increases in physiological symptoms, subjective report of anxiety, negative beliefs, memories for past failures, and negative self-images (Brown & Stopa, 2007; Chiupka, Moscovitch, & Bielak, 2012; Hinrichsen & Clark, 2003; Moscovitch, Suvak, & Hofmann, 2010; Vassilopoulos, 2005; Q. Wong & Moulds, 2011). However, some studies have also reported beneficial effects of anticipatory processing. For example, Brown and Stopa (2007) reported that both high and low socially anxious participants rated their performance in a public speech as better when it was delivered following a period of anticipatory processing compared to a period in which other task demands prevented such processing. Certainly, thinking about one’s behavior in a social situation and its effects on others in advance of the situation can be an adaptive activity. However, it is clear that, at least in some circumstances, persons with social anxiety can carry this effort to extremes. Further research is needed to examine what aspects of anticipatory processing under what conditions are most detrimental.

Mental Representation of the Self as Seen by the Audience

In response to the perception of the audience, the socially anxious individual forms (or accesses) an internal mental representation of how he or she is perceived by the audience. This representation may be an image or a vague sense of how one appears to others, which likely involves seeing oneself as if through the eyes of the audience (they are, after all, the source of potential evaluation and, therefore, there is considerable survival value in “modeling” how they think). The mental representation of the self as perceived by the audience is a composite formed from a number of different sources, and it is very likely to be distorted among persons with social anxiety disorder. For instance, this image may be informed by a sense of how one generally appears to others (information obtained in mirrors, photographs, etc.) and past difficult experiences in social situations which are consistent with negative core beliefs and self-schema. These inputs may constitute a “baseline image” (Rapee & Heimberg, 1997, p. 745) that is modified by external and internal inputs during distressing social situations. The mental representation of the self as seen by the audience should be influenced by autonomic symptoms of anxiety, particularly those that may be visible to others, such as blushing and sweating. The socially anxious individual may also monitor his or her behavior (e.g., fidgeting, wiping one’s brow) and exaggerate how it must appear to audience members, as well as what it must mean about his or her competence. Furthermore, socially anxious persons may perceive that they have social performance deficits, such as stuttering or freezing or not knowing what to say, as well as a sense that they might be coming across as “boring” or “quiet,” which would also be exaggerated in the mental representation of the self as seen by the audience. Moment-to-moment modifications of the mental representation occur based on (over)interpretations of internal feedback (e.g., “I’m feeling warm which means I’m visibly sweating”), observations of one’s own behavior (e.g., “I’m standing on the edge of this group which means I look out of place”), and the reactions of others (e.g., “That expression means I look stupid”).

Observation/Image of Self and Audience Behavior

Socially anxious persons spontaneously engage in imagery of themselves in social situations (Hackmann, Clark, & McManus, 2000; Hackmann, Surawy, & Clark, 1998), which likely has a negative effect on their mental representations of the self as seen by the audience as well as their predictions of the outcomes of social situations. Specifically, socially anxious persons are more likely than those without the disorder to spontaneously recall negatively distorted images of past events before, during, and after social situations (Chiupka et al., 2012; Hackmann et al., 1998). Hackmann and colleagues (2000) reported that socially anxious individuals described their images as: (1) recurrent, stable over time, and having been experienced for a number of years; (2) reflecting events that clustered in time around the time of onset of their social anxiety; and (3) experienced in multiple sensory modalities. The negative and distorted qualities of the images did not appear to have been moderated by positive or neutral social experiences that intervened between the imaged event and the current event. Other research has shown that negative images held in mind during social interactions or public speeches are causally related to heightened anxiety, reduced ratings of performance, and increased physiological arousal (Hirsch, Clark, Mathews, & Williams, 2003; Hirsch, Meynen, & Clark, 2004; Makkar & Grisham, 2011; Stopa & Jenkins, 2007). It is unlikely that such negatively biased imagery could have anything but a deflating effect on the mental representation of the self as seen by the audience. This effect can only be compounded by the great difficulty that socially anxious individuals have of generating neutral or positive images of themselves (Amir, Najmi, & Morrison, 2012; Moscovitch, Gavric, Merrifield, Bielak, & Moscovitch, 2011; Morrison, Amir, & Taylor, 2011).

Persons with social anxiety disorder carry forward images of social events with unfortunate outcomes with them into new situations. These images may predispose them toward anticipatory anxiety, or to the extent that they persist, with heightened anxiety and expectations of negative outcomes throughout these situations (Chiupka et al., 2012). Abundant research supports the idea that images are likely to be experienced and recalled from the observer perspective, that is, as if seeing the event unfold from a third party’s point of view. This is especially so in high-anxiety situations, and the likelihood of taking the observer perspective also increases over time (Coles, Turk, & Heimberg, 2002; Coles, Turk, Heimberg, & Fresco, 2001; Spurr & Stopa, 2003; Vassilopoulos, 2005; Wells, Clark, & Ahmad, 1998; Wells & Papageorgiou, 1999). Research on perspective-taking has its roots in social psychology, for example, Duval & Wicklund’s (1972) theory of self-awareness. In fact, the results of one early study (Ickes, Wicklund, & Ferris, 1973) suggested that taking an observer perspective may heighten levels of self-criticism and negative emotion. We assert that the “third-party observer” in the case of social anxiety disorder is the perceived audience. Of course, the problem is that the socially anxious person does not truly know the mind of the perceived audience and fills in this informational void with imagery that may be based on extremely negatively biased information.

Researchers studying imagery and emotion have suggested that affective imagery activates a network that evokes a fearful physiological, behavioral, and conceptual response—the same network that is activated when confronted with a threatening stimulus (Lang, 1979). The response to affective imagery is apparent in all individuals; however, it is intensified among anxious individuals (McTeague et al., 2009). Several studies have demonstrated that imagery elicits stronger emotional responses than verbal processing (e.g., Acosta & Vila, 1990; Holmes & Mathews, 2005; Holmes, Mathews, Dalgleish, & Mackintosh, 2006; Lang, Levin, Miller, & Kozak, 1983; Vrana, Cuthbert, & Lang, 1986). Therefore, it is likely that when socially anxious individuals engage in distorted imagery, it intensifies their negative emotional experience, and it has disruptive effects on their social performance as well (Hirsch et al., 2003; Hirsch et al., 2004; Makkar & Grisham, 2011; Stopa & Jenkins, 2007).

Preferential Allocation of Attentional Resources

Socially anxious individuals will preferentially allocate attentional resources towards detecting social threat in the environment. In fact, there are compelling evolutionary reasons why this should be the case, and the evidentiary base is strong (see Morrison & Heimberg, 2013, for a review; see Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007, for a review of this literature across the anxiety disorders). There is increasing support for the assertion that attentional bias toward threat may play a causal role in the maintenance of social anxiety disorder, as specific training procedures designed to increase or decrease attentional bias have been associated with concomitant changes in anxiety (e.g., Amir et al., 2009; Hallion & Ruscio, 2011; Heeren, Peschard, & Phillippot, 2012). Not only is it the case that socially anxious individuals monitor the environment for threat, but it also appears that they direct their attention away from positive social stimuli that might provide a more balanced and nuanced threat assessment (Taylor, Bomyea, & Amir, 2010; Veljaca & Rapee, 1998).

We also assert that socially anxious individuals allocate attentional resources toward monitoring and adjusting their mental representation of how they are perceived by the audience. Thus, socially anxious individuals attempt to simultaneously monitor the environment for evidence of evaluation, monitor their appearance and behavior for flaws that might elicit evaluation from others, and attend to and engage in the social tasks at hand. In effect, socially anxious individuals operate within the equivalent of a “multiple task paradigm,” which increases the probability of disrupted social performance (MacLeod & Mathews, 1991). Therefore, complex social tasks should result in poorer performance, due to limited processing resources, than less complex tasks. For example, Voncken and Bögels (2008) demonstrated that persons with social anxiety disorder underestimated the quality of their performance in both social interaction and speech tasks, but their assessment of their performance as poor was more similar to the ratings of objective observers in the case of the more complex social interaction task.

Comparison of Mental Representation of the Self as Seen by the Audience with Appraisal of Audience’s Expected Standard

In addition to monitoring their mental representation of how they are perceived by the audience, persons with social anxiety disorder also project the performance standard expected by the audience. Socially anxious individuals typically believe that the perceived audience members have extremely high standards for their performance, and the more they believe their behavior and appearance fall short of their estimate of the audience’s expectations, the more likely negative evaluation and its accompanying painful consequences are predicted to be. The degree to which socially anxious individuals believe their behavior meets the expectation of the audience can fluctuate based on changing perceptions of the audience, the demands of the social situation, and their own behavior. Thus, it is not uncommon for the level of social anxiety to vary while in a social situation.

Of course, fear of negative evaluation (FNE) is a core feature of social anxiety disorder (APA, 2013), and research support for this assertion is abundant (e.g., Coles et al., 2001; Hackmann et al. 1998; Horley, Williams, Gonsalvez, & Gordon, 2004; Mansell & Clark, 1999). However, fear of positive evaluation (FPE) is also a significant possibility. Wallace and Alden (1995; 1997; Alden, Mellings, & Laposa, 2004) have demonstrated that socially anxious individuals fear that initial positive performance in social interactions may raise the standards by which their future performance will be measured, yet they do not believe that they are capable of sustaining this positive performance. Consequently, they may predict that initial positive evaluation by others will ultimately result in failure to meet others’ heightened expectations.

Gilbert (2001, in press), who suggests that social anxiety is an evolutionary mechanism that facilitates non-violent group interactions, also proposed that socially anxious individuals fear elevations in status which could pose a threat/provoke conflict with more dominant others. FPE, as we have thought about it, relates to concerns about the consequences of causing others to develop a global impression of oneself that is socially threatening (i.e., “Others will think I am ‘too good’”), whereas FNE may relate to concerns about the consequences of causing others to develop a global impression of oneself as being unworthy of social inclusion (i.e., “Others will think I am ‘bad/not good enough’”).

Over the last few years, our research group has examined FPE and developed a scale for its measurement, and there is increasing evidence that FPE and FNE are distinct (but correlated) constructs (Weeks, Heimberg, & Rodebaugh, 2008; Weeks, Jakatdar, & Heimberg, 2010). When measured across multiple weeks, FPE and FNE maintain their distinctness, with no evidence that one construct prospectively predicts the other (Rodebaugh, Weeks, Gordon, Langer, & Heimberg, 2012). FPE also contributes unique variance to the prediction of social anxiety, after accounting for the variance contributed by FNE (Fergus et al., 2009; Weeks, Heimberg, & Rodebaugh, 2008; Weeks, Heimberg, Rodebaugh, & Norton, 2008).

Importantly, in one study, FPE related positively to discomfort with receiving bogus positive social feedback and negatively to perception of the accuracy of that feedback, whereas FNE did not (Weeks, Heimberg, Rodebaugh, & Norton, 2008). Similarly, FPE was positively correlated with state anxiety in response to positive social stimuli (videos of actors with pleasant facial expressions saying nice things), but not negative social stimuli (Weeks, Howell, & Goldin, 2013). Finally, treatment-seeking individuals with social anxiety disorder score higher on the Fear of Positive Evaluation Scale (Weeks, Heimberg, & Rodebaugh, 2008) than either normal controls (Weeks, Heimberg, Rodebaugh, Goldin, & Gross, 2012) or individuals with other anxiety disorders (Fergus et al., 2009). Although there is much more to learn about FPE, we now think it is reasonable to state that individuals with social anxiety disorder fear evaluation, not just negative evaluation, and a broader assessment of the evaluative fears of individuals with social anxiety disorder is routinely called for.

Judgment of Probability and Consequences of Evaluation from the Audience

The culmination of the preceding stages of the model suggests that socially anxious individuals will judge the probability and cost of evaluation by the audience to be high. Enhanced memory for past social “failures” or difficult interactions with powerful others may also make it more likely that socially anxious individuals will anticipate that current or future social interactions will not go well. In other words, socially anxious individuals focus on the discrepancy between their own mental representation of self as seen by the audience compared to their perception of the audience’s unachievable standards for their performance (FNE), or they focus on the possibility that they may have drawn unwanted positive attention to themselves that will have its own negative consequences (FPE). In either case, they are likely to overestimate the social costs of the event. Often these judgments and expectations of negative outcomes contribute to the individual’s experience of anxiety.

The Anxiety Response among Individuals with Social Anxiety Disorder

Anxiety responses can be characterized in a number of ways, and we have classified them as behavioral, physical, and cognitive. However, it is recognized that these are somewhat artificial distinctions and that one type of symptom rarely occurs without others (e.g., a negative interpretation may increase the chance of behavioral avoidance). It is also important to note here that what is classified as a symptomatic response—versus an underlying process that may cause or maintain the disorder—is also arbitrary, and that fact will be evident in sections to follow. Thus, one of the changes we have made to our model (see Figure 24.1) is the acknowledgment that the three symptom domains bi-directionally influence each of the others. Further, the symptoms experienced by the individual with social anxiety are not end-points, but rather they are perceived by the individual in various ways, and that perception may further exacerbate other symptoms as well as provide information that may negatively affect the mental representation of the self as seen by the audience.

Behavioral Symptoms

An appraisal that negative evaluation or social reprisal are likely or costly outcomes may produce overt avoidance of or escape from the social situation. Even if socially anxious individuals persist in the social situation, they may engage in a variety of self-protective behaviors intended to prevent these outcomes (Wells et al., 1995). These behaviors, typically referred to as “safety behaviors” (e.g., Clark, 2001) or “subtle avoidance” (e.g., Rapee & Heimberg, 1997), may include avoiding eye contact, standing on the outside of a crowd, or minimizing participation in a conversation by attending to one’s phone. Socially anxious individuals often believe these behaviors are necessary to complete an interaction without harm and endorse more frequent use of safety behaviors than low socially anxious individuals (Cuming et al., 2009; McManus, Sacadura, & Clark, 2008). However, safety behaviors appear to be associated with negative interpersonal outcomes.

Hirsch et al. (2004) suggested that safety behaviors might be grouped into avoidance and impression-management subtypes. In a sample of patients with social anxiety disorder, avoidance (e.g., avoiding eye contact) was associated with negative perceptions by observers, but impression-management (e.g., excessive self-monitoring and rehearsal) was not. In a recent follow-up to this study (Plasencia, Alden, & Taylor, 2011), avoidance safety behaviors were associated with higher state anxiety during a social interaction and more negative reactions from interaction partners. In this study, impression-management safety behaviors also had negative effects, appearing to impede corrections to negative predictions about subsequent interactions.

Several experimental studies suggest that safety behaviors may play an important role in the maintenance of social anxiety. McManus et al. (2008) had high and low socially anxious participants engage in two conversations, once with instructions to use safety behaviors and once with instructions to refrain from doing so. Instructions to use safety behaviors resulted in higher anxiety, more negative predictions about the outcome of the conversation, and poorer self-ratings of performance. Partners also rated the conversation without safety behaviors as more enjoyable and rated the participants as less anxious, performing better, and more likeable. Likewise, individuals with social anxiety disorder in a safety behavior reduction condition were less negative and more accurate in judgments of their performance and rated the likelihood of negative outcomes as less than those who were not so instructed (Taylor & Alden, 2010).

Physical Symptoms

Many studies have demonstrated that socially anxious individuals exhibit physiological arousal when exposed to feared social situations. Compared to individuals with other anxiety disorders, socially anxious individuals are more likely to endorse physical symptoms that may be observed by others such as blushing, muscle twitching, and sweating (Amies, Gelder, & Shaw, 1983; Solyom, Ledwidge, & Solyom, 1986). Recent research has also revealed another physical symptom of social anxiety, elevated fundamental vocal frequency (F0; Scharfstein, Beidel, Sims, & Rendon-Finell, 2011; Weeks, Heimberg, & Heuer, 2011; Weeks, Lee, et al., 2012). F0 is an objective index of the rate at which the vocal folds open and close across the glottis during phonation and is the primary determinant of the auditory impression of vocal pitch (Weeks, Lee, et al., 2012). In the study by Weeks et al. (2011), male participants took part in a role-played interaction involving the competition with another male for the attention of a female confederate. Higher social anxiety levels were associated with increased F0 peaks, providing evidence for a vocal form of social anxiety-related submissive gesturing in males. In the 2012 study, males with social anxiety disorder emitted greater F0 than low socially anxious controls, and this effect could not be accounted for by generalized anxiety or panic symptoms. More limited effects were found for female participants, although group differences were still significant. Elevated F0 has also been demonstrated in socially anxious children, in comparison to children with Asperger’s disorder and typically developing peers (Scharfstein et al., 2011), and appears to warrant much further study.

Although it is clear that social anxiety is associated with elevated physical/physiological response to social threat, it is also the case that socially anxious individuals tend to overestimate the visibility of their physical symptoms of anxiety, catastrophize about how negatively others will react to their anxiety, and become focused on those symptoms which they believe hold a high potential for eliciting negative evaluation from others (e.g., Alden & Wallace, 1995; Bruch, Gorsky, Collins, & Berger, 1989; Gerlach, Wilhelm, Gruber, & Roth, 2001).

Cognitive Symptoms

The socially anxious individual will react with situation-specific thoughts of negative evaluation in response to social stimuli (e.g., “They think I don’t know what I’m talking about”). In anxiety-provoking social situations, socially anxious individuals engage in a predominantly negative internal dialogue in which they may berate themselves (“I’m such a jerk”) or catastrophize about what other people are thinking about them (“She is not interested in me; nobody ever will be.”). Socially anxious individuals typically accept these thoughts as facts and may become increasingly focused upon them as the interaction progresses. Focusing on these thoughts may interfere with attention to the task at hand. For example, socially anxious individuals may have difficulty maintaining a conversation because they are quick to judge things they could say as “stupid” or “uninteresting.”

Underlying these commonly reported thoughts is the well-documented tendency for individuals with social anxiety disorder to engage in biased interpretation of events, interpreting neutral or ambiguous social events as negative and negative outcomes as catastrophic (Amir, Foa, & Coles, 1998; Hertel, Brozovich, Joormann, & Gotlib, 2008; Huppert, Pasupuleti, Foa, & Mathews, 2007, Roth, Antony, & Swinson, 2001; Stopa & Clark, 2000). Other studies (e.g., Hirsch & Mathews, 2000) suggest that individuals with social anxiety disorder do not have the non-threat/positive bias typical of non-anxious individuals. Other more recent work suggests that social anxiety is also associated with threat interpretations of positive social events (Alden, Taylor, Mellings, & Laposa, 2008) and failure to accept others’ positive reactions at face value (Vassilopoulos & Banerjee, 2010). Individuals with social anxiety disorder also endorsed more negative interpretations of positive events than individuals with other anxiety disorders, including panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, but not obsessive-compulsive disorder (Laposa, Cassin, & Rector, 2010).

As with preferential allocation of attentional resources, emerging research supports the hypothesis that interpretation biases play a causal role in the maintenance of social anxiety. Repeated training to access benign interpretations of ambiguous scenarios modifies interpretation bias and has resulted in anxiety reduction in adults with high social anxiety (Beard & Amir, 2008) and with generalized social anxiety disorder (Amir & Taylor, 2012).

Perceived Internal Cues

Internal anxiety cues are then used as a source of information which feeds back into the mental representation of the self as seen by the audience. Consistent with the notion of interpretation bias, “feeling shaky” may be taken to mean that others can observe the person visibly trembling or that the person may be about to lose control of his or her behavior, which may result in further negative evaluation from others. In addition to feedback from the autonomic nervous system, the individual will also receive proprioceptive information that may funnel into his or her judgment regarding the possibility of evaluation. For example, proprioceptive cues may provide information that the individual is not sitting up straight during a job interview. The individual then alters the mental representation of the self as seen by the audience to reflect a (probably exaggerated) slumping posture. This mental representation of having a slumping posture is likely to compare unfavorably with the interviewer’s projected standard of behavior. The possibility of evaluation will be judged to be more likely, which should result in increased anxiety and predictions that the interview will turn out badly.

External Indicators of Evaluation

Anxiety and, perhaps in some cases, poor social skills may function to reduce effective social performance and result in negative verbal or nonverbal feedback from the audience. For example, following employment of safety behaviors such as talking in a low voice, or avoiding eye contact, interaction partners may lose interest and begin to ignore the socially anxious individual, reinforcing the individual’s perception of their own incompetence. Among children, there is consistent evidence that socially anxious children are more likely to be ignored, rejected, and bullied than non-anxious children (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Hudson & Rapee, 2009), and there is some evidence that socially anxious adults are viewed less positively than others during interactions (Alden & Taylor, 2004). Importantly, social feedback is often indirect and ambiguous. Given an information-processing bias toward detecting and possibly remembering threatening social information, socially anxious individuals will readily incorporate these external indications of evaluation into their ongoing and long-term mental representation of themselves.

The Vicious Cycle

The socially anxious individual’s focus on external threat cues and the mental representation of the self as seen by the audience is informed by internal anxiety symptoms (i.e., physiological, behavioral, and cognitive), exacerbates state anxiety, and maintains social anxiety in the social situation. However, these processes do not operate in isolation; each component interacts with the others in the form of a positive feedback loop (consistent with the tenets of the combined cognitive biases hypothesis; Hirsch et al., 2006). For instance, the biased detection of negative audience behaviors (e.g., frowning, yawning) would likely result in greater focus on the mental representation of the self as seen by the audience (e.g., increased frequency of cognitions regarding how uninteresting one is). Focus on the mental representation of the self should not only exacerbate anxiety, but it should also increase vigilance for, and possibly detection of, negative audience behaviors, as well as the interpretation of neutral audience behaviors as negative. As individuals with social anxiety disorder look to their mental representations for information about how they come across, they necessarily see a negatively biased caricature informed by anxious feelings and assumptions about others’ evaluations when, realistically, the data needed to support such self-assessment cannot be obtained in ambiguous social situations. The person may then look to the audience to confirm his or her fears and is likely to find information consistent with his or her self-appraisals. These appraisals feed back into the mental representation of the self and result in its readjustment in a negative direction, which is a cycle likely to be repeated multiple times over the course of an ongoing social situation. This iterative process, of course, sets the person up to look forward to future social situations with less than an optimistic view, and it may predispose the person to engage in repetitive thinking about the event just transpired and its relevance for similar ones that may occur in the future.

Post-event Processing

Socially anxious individuals’ heightened concerns about their performance in social situations lead them to brood about the specifics of social events, a self-focused thought process often referred to as post-event processing (Brozovich & Heimberg, 2008; Clark & Wells, 1995) or post-event rumination (Abbott & Rapee, 2004). Socially anxious individuals may engage in post-event processing following an anxiety-evoking social event or when they anticipate a similar upcoming event (Heimberg et al., 2010; Rachman, Grüter-Andrew, & Shafran, 2000). The individual reviews his or her actions and behavior in the situation as well as the reactions and behaviors of the other individuals or audience members. By taking apart and putting together the elements of the situation and placing his or her own interpretations on them each time, the person develops a progressively more distorted view of the situation, its outcome, and his or her responsibility for that outcome. The more iterations of post-event processing in which someone engages, the further from an accurate memory of the event he or she is likely to move, but the reconstructed memory may be more easily accessible. It is likely that individuals engage in this analysis of situations to better understand their behavior, to examine it closely for potentially embarrassing moments which may require some degree of “damage control,” or to prepare themselves for the upcoming event (in an attempt to avert a perceived negative outcome).

Although a fuller review of post-event processing is beyond our scope (for a review, see Brozovich & Heimberg, 2008), it appears to be an important maintaining factor in social anxiety.

Research to date on rumination in social anxiety suggests that post-event processing increases anxiety and negative affect over time (Brozovich & Heimberg, 2011; Dannahy & Stopa, 2007; Fehm, Schneider, & Hoyer, 2007; Gramer, Schild, & Lurz, 2012; Kashdan & Roberts, 2007; Kocovski, Endler, Rector, & Flett, 2005;Kocovski, MacKenzie, & Rector, 2011; McEvoy & Kingsep, 2006) and negatively distorts memory of the actual event (Abbott & Rapee, 2004; Dannahy & Stopa, 2007; Edwards, Rapee, & Franklin, 2003; Mellings & Alden, 2000; Morgan, 2010; Morgan & Banjeree, 2008; Perini, Abbott, & Rapee, 2006). Studies that have experimentally manipulated post-event processing have shown that it also maintains negative beliefs (Vassilopoulos & Watkins, 2009; Q. Wong & Moulds, 2009). One of the most important aspects of post-event processing appears to be that it occurs not only in response to situations past, but it can be activated in response to situations in the future, as the person reviews past missteps so as to avoid future ones (Brozovich & Heimberg, 2013). This process would appear to be very important in explaining how social anxiety maintains over time and across situations—post-event processing provides the bridge from the socially anxious past to the socially anxious future. As reflected in Figure 24.1, we assert that post-event processing links directly back to anticipatory processing of situations to come.

Post-event processing may also impede progress in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Successful experiences confronting feared situations may be turned into perceived failures by the process of micro-examination of the event that is the essence of post-event processing. Thus, it may be particularly important to include cognitive exercises after exposures are completed to stem the tide of this maladaptive process. Nevertheless, the propensity to engage in post-event processing of social events does appear to be reduced after a course of cognitive-behavioral therapy (Abbott & Rapee, 2004; McEvoy, Mahoney, Perini, & Kingsep, 2009; Price & Anderson, 2011).

Emotional expression and dysregulation in social anxiety disorder

Difficulties in emotional expression and emotion regulation have been related to a number of different emotional disorders (Campbell-Sills & Barlow, 2007; Hofmann, Sawyer, Fang, & Asnaani, 2012; Kring & Sloan, 2010). As of yet, there is little research on this topic as it relates specifically to social anxiety disorder. However, the studies that have been conducted suggest that this may be a fruitful area for continued research and investigation. Although there is not a specific place to represent it in our model (i.e., Figure 24.1), we have come increasingly to see the entire set of processes that we have outlined above as one in which emotions, including but not limited to anxiety, are dysregulated, and thus we present some studies that support this opinion. Evidence is growing that socially anxious individuals are less expressive of positive emotions and have difficulty understanding their emotions. In one of our early studies on emotion dysregulation, we compared socially anxious participants to participants with generalized anxiety and controls (Turk, Heimberg, Luterek, Mennin, & Fresco, 2005). Socially anxious individuals indicated being less expressive of positive emotions, paying less attention to their emotions, and having more difficulty describing their emotions than individuals in the other two groups. In follow-up studies, social anxiety was associated with poor understanding of one’s emotional experience, controlling for generalized anxiety and depression (Mennin, Holaway, Fresco, Moore, & Heimberg, 2007; Mennin, McLaughlin, & Flanagan, 2009).

It appears that being less expressive comes at a cost for socially anxious individuals in relationships. In a recent study of heterosexual couples (Kashdan, Ferssizidis, Farmer, Adams, & McKnight, 2013), social anxiety was associated with less supportive responses to positive events shared by partners. Individuals in romantic relationships with socially anxious partners who experienced less support were more likely to terminate their relationship or report a decline in relationship quality six months later. Meleshko and Alden (1993) demonstrated that socially anxious individuals were less likely than non-anxious participants to reciprocate the self-disclosures of interaction partners. The self-protective behaviors of the socially anxious participants were associated with less liking and more discomfort on the part of their interaction partners. In a community sample, social anxiety was also associated with reduced self-disclosure in romantic relationships and friendships, among women but not in men (Cuming & Rapee, 2010).

Socially anxious individuals may also be less expressive of negative emotions. In a study by Erwin, Heimberg, Schneier, and Liebowitz (2003), treatment-seeking individuals with social anxiety disorder demonstrated higher scores on a number of anger scales (e.g., intensity of situationally experienced anger; disposition to experience anger in a wide range of situations) than non-anxious controls; however, they were more likely to suppress their anger or direct it toward themselves. Interestingly, greater anger suppression predicted poorer response to cognitive-behavioral therapy. Socially anxious individuals also appear to withhold negative emotions in romantic relationships (Kashdan, Volkmann, Breen, & Han, 2007). Kashdan and colleagues (2007) demonstrated that for people with greater social anxiety, relationship closeness was enhanced over time for those more likely to withhold negative emotions, whereas the reverse pattern was found for people with less social anxiety.

To better understand why socially anxious individuals suppress emotions, researchers have begun looking at socially anxious individuals’ beliefs. Beliefs about and appraisal of one’s success using emotion regulatory strategies appear to play an inhibitory role in socially anxious individuals’ emotional expression and implementation of emotion regulation strategies. In a study by Spokas, Luterek, and Heimberg (2009), socially anxious undergraduates reported greater use of emotional suppression than their non-socially anxious peers. They also reported greater ambivalence about emotional expression, more difficulties in emotional responding, more fears of emotional experiences, and more negative beliefs about emotional expression. Believing that emotional expression must be kept in control and that it is a sign of weakness partially mediated the association between social anxiety and emotional suppression. In another study (Werner, Goldin, Ball, Heimberg, & Gross, 2011), during an interview based onGross’s (1998) model of emotion regulation, clients with social anxiety disorder reported greater use of avoidance and expressive suppression than controls when asked about a laboratory speech task and two social anxiety-evoking situations that had occurred during the past month. They also endorsed the belief that they were less successful in implementing cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression when these strategies were employed. These regulation deficits were not accounted for by differences in emotional reactivity.

Studies are beginning to map emotion regulation deficits onto specific brain regions using functional magnetic resonance imaging (e.g., Goldin, Manber, Hakimi, Canli, & Gross, 2009; Goldin, Manber-Ball, Werner, Heimberg, & Gross, 2009), and these studies suggest that social anxiety disorder is associated with difficulty recruiting brain centers involved in cognitive reappraisal, relative to those involved in emotional suppression. These studies further build a case that individuals with social anxiety disorder inhibit the expression of a range of emotions in an attempt to control the potentially negative social consequences of that expression (e.g., rejection, negative evaluation). Although socially anxious individuals may not believe they inhibit emotions very effectively, these attempts at suppression may interfere with their interpersonal functioning. This line of thinking suggests that expressive suppression may be considered a form of safety behavior, as described by Wells et al. (1995) and Clark (2001), and that safety behaviors may serve an emotion regulatory function.

Emotion regulation is an essential part of normal human functioning, but it can go awry in a myriad of ways, and it appears to do so in social anxiety disorder. Again, this is a relatively new area of inquiry, but it appears that an important means of emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder is expressive suppression, that is, actively deciding not to express an emotion (not at all limited to anxiety) in an interpersonal context as a means of warding off unwanted consequences (e.g., potential rejection pursuant to self-disclosure of positive emotions, possible angry retaliation or negative evaluation pursuant to expressed anger). Individuals with social anxiety disorder believe that expression is dangerous and therefore suppression is the safer course, although they do not believe they do it very well. These choices are made to minimize negative outcomes, but there is some evidence to suggest that they bring on other negative consequences (the person may be less liked by others, who themselves may feel less comfortable interacting with the socially anxious person; Meleshko & Alden, 1993; see also Butler et al., 2003). Like other safety behaviors, expressive suppression may rob the person of the opportunity to observe that feared consequences may not occur or, if they do occur, in a manner less extreme than imagined.

Closing comments

We originally proposed a cognitive-behavioral model of social anxiety more than 15 years ago (Rapee & Heimberg, 1997) and provided the first comprehensive update more recently (Heimberg et al., 2010). In this chapter, we have provided a summary of that model, further updated to reflect “conditions on the ground” at the current time. In addition to providing additional research support for existent aspects of the model, we have made further changes that more fully recognize the role of anticipatory processing, the interplay among behavioral, cognitive, and physical symptoms of anxiety, and the important role of post-event processing in bridging the experience of social anxiety from one situation to the next. We have expanded our presentation of the role of emotional suppression and dysregulation in social anxiety. As always, there is much research that needs to be completed before all aspects of this model can be fully validated, and we look forward to the next several years as this process unfolds.