Appendix

Images and Ephemera from the 2016 Philip K. Dick Conference

Images

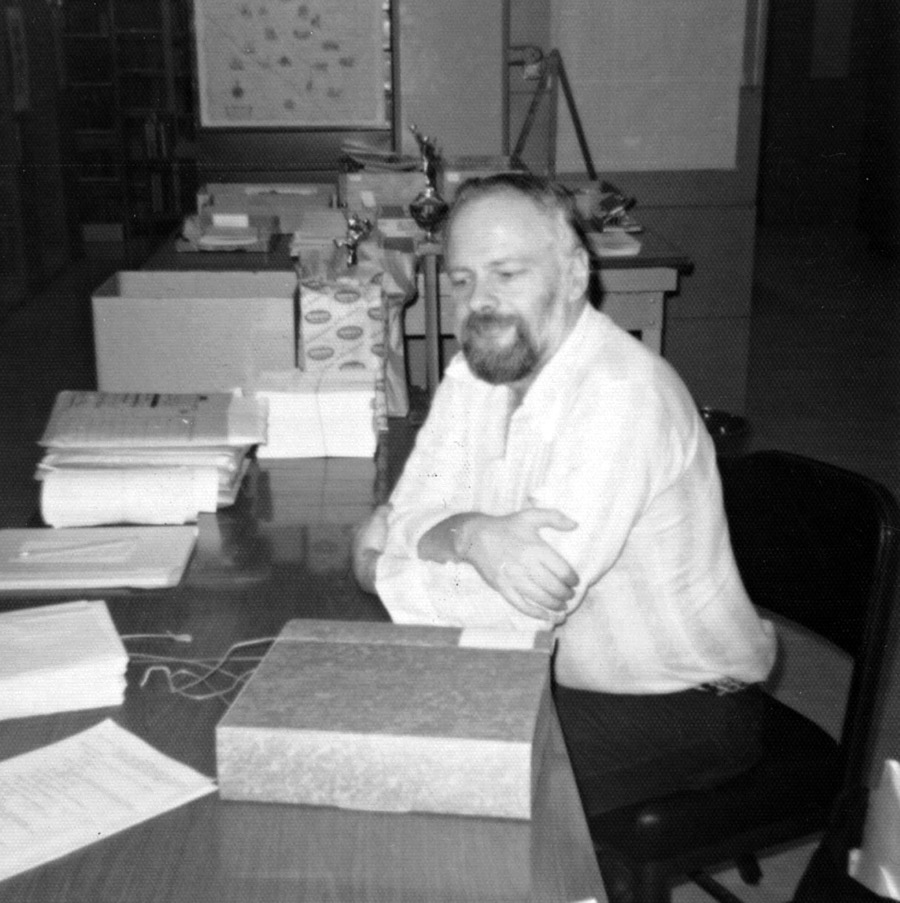

Our conference mounted an art show and display of California State University, Fullerton Special Collections material as well as running panels and paper sessions. We share a selection of key images that emerged from that and surrounding events: a photo of Dick in the Special Collection archives of the Pollak Library, organizing his materials for deposit (for which he was paid a small stipend); a map by artist Felipe Flores, “Philip K. Dick in Orange County,” from the Hibbleton Gallery show, downtown Fullerton, 2015; the conference poster portrait of PKD; and selected images from “Here and Now,” the show in the Atrium Gallery of the Pollak Library at CSUF, 2016, in which artists responded to four key works: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, “Minority Report,” The Man in the High Castle, and The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch.

Philip K. Dick in the CSUF Special Collection archives of the Pollak Library (CSUF Pollak Library Special Collections, circa 1972).

Felipe Flores, “Philip K. Dick in Orange County” (2015). Approximately top to bottom, left to right:

St Jude’s Hospital—“Tell him you’re bringing Johnny into the emergency room at St. Jude Hospital in Fullerton. Tell him to be there.”

Placentia Barrio—“Upon leaving the freeway near Anaheim—he took the wrong exit ramp and wound up in the town of Placentia—he discovered Mexican buildings, low-rider Mexican cars, Mexican cafes, and little wooden houses filled with Mexicans. He had stumbled onto a barrio for the first time in his life. The barrio looked like Mexico, except that there were Yellow Cabs. Nicholas had made actual contact with the world of his visionary dream.” (continued on page 190)

“It was spectacular; here he was, raised in Berkeley, sitting in his modern apartment (Berkeley has no modern apartments) in Placentia, wearing a florid Southern California–style shirt and slacks and shoes; already he had become part of the lifestyle here. The days of bluejeans were gone.”

“I really don’t understand much of what they say. I just get impressions of their presence. They did want me to move down here to Orange County; I was right about that. I think it’s because they can contact me better, being near the desert with the Santa Ana wind blowing a lot of the time. I’ve bought a bunch of books to do research, like the Brittanica.”

“Orange County isn’t nuts; it’s very conservative and very stable. The nuts are up north in LA county, not here. I missed the nut belt by sixty-five miles; I overshot. Hell, I didn’t overshoot; I was deliberately shot down here, to central Orange County.”

Richard Nixon/Fremont Ferris Library—“Being politically oriented, Nicholas had already noted the budding career of the junior senator from California, Ferris F. Fremont, who had issued forth in 1952 from Orange County, far to the south of us, an area so reactionary that to us in Berkeley it seemed a phantom land, made of the mists of dire nightmare, where apparitions spawned that were as terrible as they were real—more real than if they had been composed of solid reality. Orange County, which no one in Berkeley had ever actually seen, was the fantasy at the other end of the world, Berkeley’s opposite; if Berkeley lay in the thrall of illusion, of detachment from reality, it was Orange County which had pushed it there. Within one universe, the two could never coexist.”

Slums of Brea…—“Strung out on injectable Substance D already, she lived in a slum room in Brea, upstairs, the only heat radiating from a water heater, her source of income a State of California tuition scholarship she and won. She had not attended classes, as far as he knew, in six months.”

Yorba Linda—“He trod across the wall-to-wall carpet, which depicted in gold Richard M. Nixon’s final ascent into heaven amid joyous singing above wails of misery below. At the far door he trod on God, who was smiling a lot as He received his Second Only Begotten Son back into His bosom.”

Blue Chip Redemption Center—“It’s the fucking Blue Chip Redemption Stamp Center in Placentia,” Charles Freck said.

Knott’s Berry Farm—“In the kitchen doorway Ruth appeared, holding up a stoneware platter marked SOUVENIR OF KNOTTS BERRY FARM. She ran blindly at him and brought it down on his head, her mouth twisting like newborn things just now alive. At that last instant he managed to lift his left elbow and take the blow there; the stoneware platter broke into three jagged pieces, and, down his elbow, blood spurted. He gazed at the blood, the shattered pieces of platter on the carpet, then at her.”

Thrifty Drugs—“But in actuality the Thrifty (Drug Store in Fullerton) had a display of nothing: combs, bottles of mineral oil, spray cans of deodorant, always crap like that. But I bet the pharmacy in the back has slow death under lock and key in an unstepped-on, pure, unadulterated, uncut form, he thought as he drove from the parking lot onto Harbor Boulevard, into the afternoon traffic.”

Fullerton—“You have one private pol,” Jason interrupted, “He’s sixty-two years old and his name is Fred. Originally he was a sharp-shooter with the Orange County Minutemen; used to pick off student jeters at Cal State Fullerton.”

Cal State Fullerton—“Once, when I lectured at the University of California at Fullerton, a student asked me for a short, simple definition of reality. I thought it over and answered, ‘Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, it doesn’t go away.”

Disneyland—“But when he got down to the LA area, in particular down to Orange County and Disneyland, and had had a chance to cruise around in his old Plymouth, he discovered something unexpected, although more or less in fun I had suggested it to him. Parts of that region resembled his Mexico dream. I had been right.”

Melody Christian Center—“I wanted her to go to Melodyland and testify that Jesus had cured her.”

Anaheim Suburbs—“Life in Ahaheim, California, was a commercial for itself, endlessly replayed. Nothing changed; it just spread out farther and farther in the form of neon ooze. What there was always more of had been congealed into permanence long ago, as if the automatic factory that cranked out these objects had jammed in the ‘on’ position. How the land became plastic, he thought, remembering the fairy tale ‘How the Sea Became Salt.’ Someday, he thought, it’ll be mandatory that we all sell the McDonald’s hamburger as well as buy it; we’ll sell it back and forth to each other forever from our living rooms. That way we won’t even have to go outside.”

Anaheim Lions Club—“Gentlemen of the Anaheim Lions Club, the man at the microphone said, “we have a wonderful opportunity this afternoon, for, you see, the County of Orange has provided us with the chance to hear from—and then put questions to and of—an undercover narcotics agent from the Orange County Sheriff’s Department.”: He beamed, this man wearying his pink waffle-fiber suit and wide plastic yellow tie and blue shirt and fake leather shoes; he was an overweight man, overaged as well, overhappy even when there as little or nothing to be happy about.”

Anaheim Stadium—“Hey,” Donna said with enthusiasm, “could you take me to a rock concert? At the Anaheim Stadium next week? Could you?

Episcopal Church—“I can’t give the name of Sherri’s church because it really exists (well, so, too, does Santa Ana), so I will call it what Sherri called it: Jesus’ sweatshop.”

UCI Medical Center—“The chief cardiologist at the Orange County Medical Center had exhibited Fat to a whole group of student doctors from UC Irvine. OCMC was a teaching hospital. They all wanted to listen to a heart laboring under forty-nine tabs of high-grade digitalis.”

“Being crazy and getting caught at it, out in the open, turns out to be a way to wind up in jail. Fat now knew this. Besides having a county drunk tank, the County of Orange had a county lunatic tank. He was in it … the County of Orange would bill him for his stay in the lock-up…. So now he had learned something else about being crazy: not only does it get your locked up, but it costs you a lot of money.”

Tustin Theater—“A couple of days later the three of us drove up Tustin Avenue and took in the film VALIS once more.”

Santa Ana, Philip K. Dick’s Apartment—“Time has been overcome. We are back almost two thousand years; we are not in Santa Ana, California, USA, but in Jerusalem, about 35 C.E.”

Fiddler’s Three Coffee—“Seated with Jim Barris in the Fiddler’s Three coffee shop in Santa Ana, he fooled around with his sugar-glazed doughnut morosely.”

Orange County Jail—“Wonderful. Now what was I supposed to do? They really had me. I cooperated or I went to the Orange County Jail. And people died—were clubbed to death—at the Orange County Jail; it happened all the time. Especially political prisoners.”

Downtown Santa Ana—“One of the reasons Beth left Fat stemmed from his visits to Sherri at her rundown room in Santa Ana. Fat had deluded himself into thinking that he visited her out of charity. Actually he had become horny, due to the fact that Beth had lost interest in him sexually and he was not, as they say, getting any.”

“Meanwhile he had entered therapy through the Orange County Mental Health people.”

“Driving back to the modern two-bedroom, two bathroom apartment in downtown Santa Ana, a full-security apartment with deadbolt lock in a building with electric gate, underground parking, closed circuit TV scanning of the main entrance … he now lived in this fortress-like, or jail-like, full security new building set dead in the center of the Mexcian barrio.”

Gateside Mall—“Donna worked behind the counter of a little perfume shop in Gateside Mall in Costa Mesa, to which she drove every morning in her MG.”

Orange County Civic Center—“He did not feel like returning right away to the Orange County Civic Center and room 430, so he wandered down one of the commercial streets in Ahaheim, inspecting the McDonaldburger stands and car washes and gas stations and Pizza Huts and other marvels.”

John Wayne Airport—“Around me the plane became substantial. David sat reading a paperback book of T.S. Eliot. Kevin seemed tense. “We’re almost there,” I said, “Orange County Airport.”

Cliff Cramp, conference poster portrait of PKD (2016).

Caleb Havertape, “San Francisco,” illustration for Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (2016).

Cliff Cramp, “Police Hovercraft,” illustration for Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (2016).

Cliff Cramp, “Association Owl,” illustration for Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (2016).

Dallin Bifano, “San Francisco,” illustration for Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (2016).

Caleb Havertape, “Precogs,” illustration for “Minority Report” (2016).

Garrett Kaida, “Chase,” illustration for “Minority Report” (2016).

Cliff Cramp, “German Sector,” illustration for The Man in the High Castle (2016).

Cliff Cramp, “The Gate,” illustration for The Man in the High Castle (2016).

Dallin Bifano, “Japanese Empire Aircraft,” illustration for The Man in the High Castle (2016).

Caleb Havertape, “Mars Outpost,” illustration for The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (2016).

Cliff Cramp, “Pluto,” illustration for The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (2016).

Cliff Cramp, “Mars Outpost,” illustration for The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (2016).

Garrett Kaida, “Miss Fugate,” illustration for The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (2016).

Zines

As Jonathan Lethem and Samuel Sousa just described in “Dick’s SoCal Dream,” zines play a key role in Southern California culture, especially in relation to the punk music that Dick admired; they play a key role as well in the history of science fiction literature generally, connecting fans as far back as the pulp era; Lethem’s keynote explains the importance of Paul Williams’s zines: first, in inventing rock and roll criticism … then, in the Philip K. Dick Society Newsletter, launching PKD scholarship toward its current ubiquity. Two zines came out as part of our constellation of Dick events, and, mindful of the history above, we offer brief selections from them as a counter-gesture to what Lethem calls “the gentrification of Philip K. Dick” in books like our present volume. Included are short introductions by Christine Granillo from Philip K. Dick in Orange County (2015) and by Nicole Vandever and by David Sandner from The Aramchek Dispatch (2016).

From Philip K. Dick in Orange County

A Brief Account of How I Became a Dickhead

The Philip K. Dick in Orange County project started last year during a Digital Literary Studies class I took with Dr. David Sandner at Cal State Fullerton. As a class, we created a website that was dedicated to Philip K. Dick’s time in Orange County and his connection to Cal State Fullerton. Before I took this class, my only knowledge of Philip K. Dick was from the story “The Electric Ant,” so I confess: at the time this project started, I was a newbie at PKD. Yet, once I started reading more of Philip K. Dick’s works, it clicked. I was an instant fan. Like David Gill says in the short film Why Philip K. Dick Matters when I got hooked, “I did that thing that Dickheads do, they go and they buy a giant stack of books.” I buy more of his books before I’ve even finished reading the ones I already have. When I think of why I like Philip K. Dick so much, I realize I appreciate the social commentary he provides, the scary predictions he forecasts in his novels that somehow feel all too real today, and the astonishing way he portrays humanity.

The first novel I read was A Scanner Darkly. I became tuned in. I began to understand what the fuss was all about. I tripped out over the mention of sights I am familiar with and grew up around, some that no longer exist, like the La Habra Drive-In that was just down the street from the house I grew up in. It felt surreal to see the landscape of the Orange County that I take for granted mapped out in the novel I was holding in front of me. Not only was Orange County mapped out but it was mapped out in a novel that rejected the plastic, conservative image OC has crafted for itself. Rather, it called this image into question and displayed the underbelly that exists within Orange County. It was this, the presence of Orange County in his novels, that the Digital Literary Studies class was interested in exploring. This is what we wanted to put on display on our website. Philip K. Dick is a famous author, 11 of his books or short stories have been adapted into films—some of them, like Blade Runner and Minority Reports, were huge successes. It seems like something Orange County should be proud of, yet somehow the legacy of Philip K. Dick sleeps quietly through the night under the cover of a thin blanket. It’s time to pull the blanket. On to the show…

From The Aramchek Dispatch

Speculative Fictions and the Outsider: Everyone in This Zine Is a Loser

Hello! Thanks for picking up our zine. It was put together with loads of time, sweat, tears, and ink by our editors, our reader panel, and, of course, our contributors. I’ll get to that process in a bit, but most importantly and more immediately interesting (to me, at least) is, What exactly is a zine? And what does it have to do with speculative fictions? Spending a long while in the library, visiting a couple zine-related events, I’ve come up with my own definitions. But first, here’s some from the OED:

AMATEUR. Etymology: amateur < Latin amātōr-em, lover< amā-re to love.

MONSTER. n. Originally: a mythical creature which is part animal and part human, or combines elements of two or more animal forms, and is frequently of great size and ferocious appearance.

LOSER. n. One who loses or suffers loss. / A squanderer or waster (of time).

I thought about these three words while helping to assemble this beast. They are words I’ve come to treasure in my studies of literature and spec fic, because they represent the nature of the writer, the outsider, and the SF/Fantasy fan, and the creations that come from all three.

We are all AMATEURS, and ACADEMIA is a fancy word for FANDOM.

A zine is made on the ground, totally DIY, expressing the traditions and cares, ephemeral as they may be, of the editors and contributors. It seemed perfect for our club’s aim—showing the world (a small part of it, if not just ourselves and immediate friends and family) the important history and present of speculative fictions at our university and what we’re doing now that keeps it all relevant.

[Zines, as we know them, can trace their roots back to science fiction fanzines way back in the 30s (awesome, right?). It all started with people reimagining the world, writing it down, and talking to each other about their stories through printed, folded, floppy things. Like the one you hold now.]

When Michelle Hickethier, Paige Patterson, Jasmine Romero, Emma Strand, and I came together to form the Science Fiction & Fantasy Lit Club, we wanted to create an extended version of our little fan community. We, as students who sometimes feel like the pages upon pages we read and write would amount to nothing outside our own heads, wanted to share the excitement. We, as students of CSUF, got very excited when we heard about our university’s history and holdings—“we have Bradbury? AND Herbert??”—but felt like nobody knew or cared.

So we thought we’d start a club.

Why not? We said, rallying after class, coming up with wild and impossible ideas for meetings

Why not? We said, filling out forms and putting down cash to register the club, wrestling for rooms and tech access.

Why not? We said, begging people to share their ideas and creations in a zine, unsure but unchecked and excited.

We never got our zine off the ground, until Christine Granillo, president of the Creative Writing Club, decided she didn’t have enough on her pallet and wanted to collaborate on a zine to be released at the Philip K. Dick conference. She had created one before, which was released as collection of local authors and artists titled Philip K. Dick in the OC. It made its debut at the Hibbleton gallery in downtown Fullerton, and so many fans and enthusiasts came out that night to share in the mutual excitement.

Big things, small packages. We’re all just students, here. We’re used to writing academic papers, using MLA, APA, but here you’ll find them MIA. Quick, snappy, the unpolished, but nonetheless witty and important for its swiftness and ephemerality. We hope to channel the sublime of the punk, rocking the academia tree with our humble zine. We’re hardcore amateurs.

Monster, outsider.

By creating a zine, something ephemeral, without barcode or accolades, and by using it to celebrate science fiction & fantasy, we are outside of a norm. None of this is USEFUL. Also, all of us are so DIFFERENT. It shocks me every time, at club meetings, in classes. We’re colorful and queer, of all genders, nervous and loud, big and small and young and old. Some of us have visions of the future, or really hope there’s a dragon left alive, somewhere; some of us just really wish we had a superpower. But we all come together, different, imagining. All of us who are reading or building this zine ended up in Speculative Fictions. How did we get to this strange horizon?

It’s undeniable that the roots of speculative fiction may not have grown from the Outsider in our modern, inclusive sense. Zines, says Stephen Duncombe, had their roots in a base where the white, male, heterosexual is the norm. Le Guin, SF queen, calls out the sexism inherent in her field in “American SF and the Outsider” (and most of her works following). And I love LOTR, but can we talk about Orcs? Even with questionable representation within a great many works, it is speculative fiction as a form that requires us to pose questions to reality, encourages us to imagine the world differently by seeing its faults, its quirks, tweaking elements and creating new ones from them.

“Together,” says Duncombe, zinesters “give the word ‘loser’ a new meaning, changing it from insult to accolade, and transforming personal failure into an indictment of the alienating aspects of our society.” The point of the zine, is that there IS NO TARGET MARKET. The Zine—the creation and bastion of the outsider, the purposeful loser—and Speculative Fictions—a space where the norm is necessarily questioned. This speculation is marked, sometimes uncomfortable, strange in a way that’s not packagable, exotic in a way that’s not pretty—it is MONSTROUS.

In the following pages, you’ll read Magical Manifestos, reality-bending twist endings, ruminations on our celestial origins, and ordinary people writing about and drawing the strange things they love. These pages are fragments of what’s important to a number of very different people, but they all express it speculatively and fictionally. Imagining beautiful things, questioning and drawing out the strangeness of our world.

“In the zine world, being a loser … is something to yell from the rooftops.”

—Notes from Underground, Stephen Duncombe

So why did we make this zine? We’re worrying a bit now, down to the wire—how can we print this thing quick and dirty—you can smell the we-should-have and how-much-time on us; the odor of anything done passionately. We come together with our different ways of doing things and our multiple left feet. With our visions of other worlds, and the future. We worked hard between our day jobs and night studies to make something that doesn’t matter one bit to the vast timeline of the universe. This stapled paper booklet will be read, decay, and be dust faster than the smallest star in the furthest part of the galaxy. It is necessarily ephemeral in form (“everything in life is just for a while,” says Dick). It is the definition of a LOSER.

And so, here is our attempt at creation. Our authors are diverse—some consider themselves writers, some have never written a story in their lives—but we have come together for a reason. To be an outsider, to love speculative fiction, to make a zine—to lose. That’s what we’ve attempted here.

“It’s easy to win. Anybody can win.”

—Philip K. Dick, A Scanner Darkly

Introduction—On Your Last Chance to be Human… On It Being Already Too Late…

“I have a bad attitude … so I rebel. And writing SF is way to rebel…. SF is a rebellious art form and it needs writers and readers and bad attitudes—an attitude of “Why?” or “How Come?” or “Who Says?”

—Philip K. Dick

Why?

Zines, too, have bad attitudes. They go out for cigarettes with your last twenty and you know they’re not coming back. They hang out in alleyways or under bridges. They know where the bodies are buried—they might have put them there.

Zines just won’t get out of your face. They exist, in a real, tangible, messy way. You hold it in your hands, right here and now—you can’t just click away this time—you have to close the cover, you have to toss it down if you want to refuse it.

But you don’t turn away. You will not refuse. Why? Could this be your last chance to be human? Isn’t that the always-broken promise of art? And especially of art like this—not made for capitalist consumption by corporations (who are more people than people, the law now says), but instead made anyway, by hands and glue and tape and nails enough for a crucifixion, probably yours. (Does that make you want to stop, or to read on all the more?)

“All art is quite useless,” Oscar Wilde whispers in George Orwell’s ear as they conceive their love child, Philip K. Dick. Mary Shelley flies in as a good fairy and bestows on the baby a gift: visions of the future. But another fairy, of more malignant disposition, angry at being neglected, sends a curse—but it is the same as the gift: visions of the future!

Still you will not stop reading!

* * *

So it’s all in good fun, isn’t it? Just entertainment? It’s only science fiction. Just a zine. But what if this Aramchek Dispatch is written in code? What if it contains a message meant only for you alone? What if it tells truth? What if it reveals the face of God?

What, I wonder, will finally prevent you from breaking the code? Your disbelief? Your busy schedule? Your boredom? Your fear?

How Come?

This zine you have refused to stop reading is released in conjunction with the 2016 Acacia Philip K. Dick Conference on the campus of California State University, Fullerton, April 29 and 30.

Now the origin story of the conference lies in a website, Philip K. Dick in the OC, created by my Digital Literary Studies class for reasons obscure to us. Maybe messages microwaved into our brains by our alien overlords. We wanted to know about PKD and his presence here in Orange County, almost among us, in an alternate now. He seems to have a message, slightly garbled, almost mislaid, we need to hear.

But we created a zine back then, too, of which this one is the hideous progeny. How come? Websites have a far reach but are a ghostly presence; they are but spectral flickers of uncertain existence. A zine, however, abides—it presses against your flesh. Stitched together from unhallowed parts and endowed with life by its creators—those mad scientists—it is less ghost and more Frankenstein’s monster, lifting the curtain on you while you sleep, asking for your love. Surely you will take the living hand, so warm and capable, held out to you? We made a zine then, also called Philip K. Dick in the OC, to go with our newborn website. There was an art show at the Hibbleton Gallery in downtown Fullerton, with art on the walls … and the zine to read.

And just as the first website begat the zine and art show … so they all begat another website, of greater scope: SF at CSUF. And the website looked about itself and it was good, studying the many facets of SF at Cal State Fullerton: PKD and more … steampunk and the pulps in our Special Collections, and on into the shiny future. And lo, the website begat the conference which begat an art show and special collections display as part of the conference. But something was missing, and all must move in an eternal return … and so we have a zine. This one you now cannot stop reading even if you tried.

This one you hold shows you life is but a zine. It contains multitudes. It is the child of giants that lived in those days.

* * *

What if you broke the code here, disguising the message meant for your eyes alone, only to find you, yourself had encoded the message hidden here? Will you find your own name signed here on these unhallowed pages, suddenly implicated in every sordid thing, laid bare, now alien to you? Will you wonder: did you mean to send the message or hide it forever?

Will you burn your notes and erase your memories?

Will you write an answer to the message here first before you burn your notes and erase your memories? What will you say in that impossible conversation with yourself that you will refuse to remember but will never stop striving to know? What is it you have to say—that one thing at the tip of your tongue that you will make yourself forget?

This zine is a burning bush. It is a fall from a dizzying height. This zine is the kiss that kills. A dream that cannot be spoken, but here it is.

Who Says?

The zine you still insist on reading, despite all warnings, was brought to life by the combined dark powers of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Club and the Creative Writing Club. Wholly a student production, wrought of their energy and insight, as a reaction against the terrible insistence of Philip K. Dick’s art. Art makes art. Come listen in to what can only be alien communications between distant worlds, where, in languages fabulous and unknown, words cross the stars in one final chance to fail better than we ever have before … these writers will strive and fail to be human as a kind of gift to you (lest you fail without striving)—a hand held out on a rainy, dismal night by the creature you yourself have made—a dream you thought your own that you find, tears in your eyes, is shared by others, despite everything you thought you knew.

Who says? We do, dreaming together even as we live forever sequestered by all we cannot know or be. We dream together anyway, despite everything.

Read on!

* * *

What if I’m lying and there is no code but you break it anyway and discover a secret of untold significance? For what if the code is everywhere and the key meant for only you to discover here? What sort of prophet will you be? Mad, raving on street corners or at the edges of freeway off ramps? Or will you write science fiction, alternate histories? Or will you put out a zine, and place it in the hands of those who may understand?

I’m talking about you. Bring your questions. Bring your fears. Read with a bad attitude. We’re counting on you to break the code. We’re counting on you to fail but to fail in the only way that matters… We’re counting on you to rebel. It’s all you’ve got … your last chance … already too late to take … but how human to strive to take it anyway! How amazing!

And remember: Philip K. Dick was right!