Is it possible to make a poster of unlimited dimensions, a poster as long or high as you care to make it? A poster three foot by five, twelve foot by two and a half, six foot by ten…?

Posters are usually designed as single entities, enclosed within their particular dimensions, and then pasted up on walls and hoardings three or four together and sometimes more. Now it often happens that a poster is simply not designed to be displayed side by side with its twin, and some very odd things may happen to the form if it is so displayed. If (as in a recent example) two faces in profile are looking into the poster from right and left, sniffing at the soup or exclaiming over the apéritif that occupies the centre of the design, when several of these posters are put up together the result is a series of strange Janus-faced creatures looking both ways at once, an image that was far from the mind of the designer. Every figurative element of the poster that is cut by the right-or left-hand edge will inevitably combine in some unforeseen way with the poster next door. This never happens to posters with a central image, as described in the last chapter.

But there is a way of getting round this problem, and this is the method already used for designing wallpaper and materials for clothing and furnishing. Here the left hand side must know what the right hand is doing, the top must know the bottom. If some form is cut in half by the right-hand margin, then the left-hand margin must have a corresponding form for it to link up with, for the right of one poster joins on to the left of its neighbour.

It is therefore in certain cases possible to design posters on the same lines as wallpaper, posters with no set limits, that can be pasted up on a wall by the dozen to form one great poster of any size you like.

An Italian example of this – but of a product sufficiently well known to English readers – is the Campari advertisement displayed in underground stations. It is hard to say for sure whether it is one poster or many. The red background holds the whole thing together, while the name of the product is cut to pieces and put together again in such a way as to make an endless game for the eye. Meanwhile the impression of depth is conveyed by printing the word CAMPARI in bigger or smaller letters. The eye is attracted by this interplay of various combinations, and runs easily back and forth (often in the malignant hope of finding a mistake somewhere). This poster gets across its message even if you just catch a glimpse of it, if people are standing in front of it, or if you pass it in a train at speed. In this particular case the series can only run horizontally, but clearly it is also possible to make posters combine vertically as well. The motif which links one poster with its neighbour can also be quite distinct from the thing advertised. For example, one might put a red apple on a background of black and white check or horizontal lines, or have a coloured band running right through the series of posters and bearing the overprinted name of the product.

The edges of a poster are therefore worthy of special consideration. They may serve as neutral areas to isolate one poster from the others around it, or as calculated links in a series. In any case one can never ignore them when one designs a poster, and certainly not if one wants to avoid the unpleasant surprise of seeing one’s work come to nothing the moment it goes up on a wall.

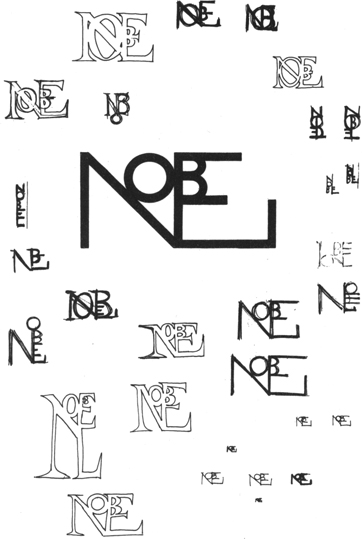

Trademark of the ‘Nobel Prize’ editions, devised with reference to old Byzantine, Christian and Greek writing. Various working stages are visible in this sketch, as well as tests of legibility. The graphic form is contained within two squares. Such a mark must be legible even if reduced to the smallest proportions.