Knowing children is like knowing cats. Anyone who doesn’t like cats will not like children or understand them. Every day you see some old woman approach a child with terrible grimaces and babble idiocies in a language full of booes and cooes and peekiweekies. Children generally regard such persons with the utmost severity, because they seem to have grown old in vain. Children do not understand what on earth they want, so they go back to their games, simple and serious games that absorb them completely.

To enter the world of a child (or a cat) the least you must do is sit down on the ground without interrupting the child in whatever he is doing, and wait for him to notice you. It will then be the child who makes contact with you, and you (being older, and I hope not older in vain) with your higher intelligence will be able to understand his needs and his interests, which are by no means confined to the bottle and the potty. He is trying to understand the world he is living in, he is groping his way ahead from one experience to the next, always curious and wanting to know everything.

A two-year-old is already interested in the pictures in a story book, and a little later he will be interested in the story as well. Then he will go on to read and understand things of ever increasing complexity.

It is obvious that there are certain events that a child knows nothing of because he has never experienced them. For example, he will not really understand what it means when the Prince (very much a fictional character these days) falls in love with the equally fictional Princess. He will pretend to understand, or he will enjoy the colours of the clothes or the smell of the printed page, but he will certainly not be deeply interested. Other things that a child will not understand are: de luxe editions, elegant printing, expensive books, messy drawings, incomplete objects (such as the details of a head, etc.).

But what does the publisher think about all this? He thinks that it is not children who buy books. They are bought by grown-ups who give them as presents not so much to amuse the child as to cut a (sometimes coldly calculated) dash with the parents. A book must therefore be expensive, the illustrations must use every colour in the rainbow, but apart from that it doesn’t matter even if they are ugly. A child won’t know the difference because he’s just a little nincompoop. The great thing is to make a good impression.

A good children’s book with a decent story and appropriate illustrations, modestly printed and produced, would not be such a success with parents, but children would like it a lot.

Then there are those tales of terror in which enormous pairs of scissors snip off the fingers of a child who refuses to cut his nails, a boy who won’t eat his soup gets thinner and thinner until he dies, a child who plays with matches is burnt to a cinder, and so on. Very amusing and instructive stories, of German origin.

A good book for children aged three to nine should have a very simple story and coloured illustrations showing whole figures drawn with clarity and precision. Children are extraordinarily observant, and often notice things that grown-ups do not. In a book of mine in which I tried out the possibilities of using different kinds of paper, there is (in chapter one, on black paper) a cat going off the right hand edge of one page and looking-round the corner, as it were – into the next page. Lots of grown-ups never noticed this curious fact.

The stories must be as simple as the child’s world is: an apple, a kitten (young animals are preferred to fully grown ones), the sun, the moon, a leaf, an ant, a butterfly, water, fire, time (the beating of the heart). ‘That’s too difficult,’ you say. ‘Time is an abstract thing.’ Well, would you like to try? Read your child the following paragraph and see if he doesn’t understand:

Your heart goes tick tock. Listen to it. Put your hand on it and feel it. Count the beats: one, two, three, four…. When you have counted sixty beats a minute will have passed. After sixty minutes an hour will have passed. In one hour a plant grows a hundredth of an inch. In twelve hours the sun rises and sets. Twenty-four hours make one whole day and one whole night. After this the clock is no good to us any more. We must look at the calendar: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday make one week. Four weeks make one month: January. After January come February, March, April, May, June, July, August, September, October, November, December. Now twelve months have passed, and your heart is still going tick tock. A whole year of seconds and minutes has passed. In a year we have spring, summer, autumn and winter. Time never stops: the clocks show us the hours, calendars show us the days, and time goes on and on and eats up everything. It makes even iron fall to dust and it draws the lines on old people’s faces. After a hundred years, in a second, one man dies and another is born.

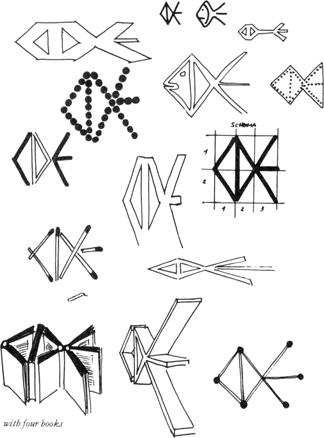

Variations on the trademark of the Club degli Editori (Publishers’ Association), the emblem being a fish. These sketches were made to see how far it can be changed and still remain recognizable. In some kinds of advertisement or in setting up stands at exhibitions, for example, the trademark is sometimes a wooden construction several yards high. Will it still be recognized as such? In what ways can it be varied without essential change? At the bottom left is a photo of four books stood on edge and opened in such a way as to form the trademark. This idea was actually used in an advertisement.

Exercises in altering and deforming a well-known brand name until it reaches the limits of legibility.