Chapter Eleven: War!

It was three miles to the ranch where Plato and Beulah and Rufus stayed. I kept to the creek for a mile or so and then got up on the county road when the creek made its big horseshoe bend to the north.

Boy, I felt good! The air was sweet with wildflowers and the sunshine warmed my back. My eyes worked, my aches and pains had gone away, and I could feel the muscles inside my skin, straining to get out and do handsprings.

I made a mental note to myself: “Next time you get to feeling poorly, go see Madame Moonshine because she can cure more ills than Black Draught.”

(I knew about Black Draught because Loper once used it to cure me of a case of worms. Don’t try it unless everything else has failed and it’s come down to a choice between Black Draught and certain death.)

It was late afternoon when I reached the outbuildings of the ranch and by that time I had worked out my strategy. Instead of busting in and having a showdown right away, I would lurk around and check things out. Also give my highly conditioned body a chance to recharge.

I didn’t want to underestimate the magnitude of the task before me. Taking on Rufus would be a handful, even on a good day.

I went creeping through some tall grass on the west edge of the place. I could see Billy down at the corrals, working with a young horse. Didn’t see any signs of Beulah or Rufus.

I spotted a pile of old cedar posts and headed for it. I would set up a scout position there and just, you know, let the pot bubble for a while.

I reached the post pile and was peering around a corner when I heard a noise. Sounded like . . . it was kind of hard to describe, but it sounded a whole lot like teeth chattering. And it was coming from inside the pile. I cocked my head and listened.

“Who’s in there?”

“Nobody,” said a squeaky voice.

“Huh, you expect me to believe that? You ain’t dealing with just any old slouch. You’d best come out before I get riled.”

“Who are you?”

“Who I am is irrelevant. The order is for you to come out before I have to make kindling out of this post pile.”

“Okay, I’m coming, but don’t bite for Pete’s sake, my skin tears very easily!”

Out came a spotted bird dog with rings around his eyes that made it appear that he was wearing glasses. He was trembling all over. You guessed it: Plato, my old rival in the love-of-Beulah department. We’d met once or twice before, but we weren’t what you’d call bosom friends.

“Hank? Oh thank heaven it’s you!”

“It may be too soon to thank heaven, Plato.”

He slapped his paw against his cheek. “At first I thought you were that Doberman. This has been an incredible experience. Would you believe five days in the post pile, I mean actually in fear of my life! I’m telling you, man, it’s been . . .”

“Where’s Rufus?”

Plato’s eyes widened. “I don’t know where Rufus is, and that’s okay. I’ve got nothing at all against the dog. I’m perfectly willing to relate to him . . . why do you ask?”

“I’m looking for him.”

“Good heavens! Why?”

“Grudge.”

“Grudge? Okay.” He started backing toward the post pile. “Well, my position is very simple, Hank.”

“Your position better stay out of the post pile.”

“Sure, okay, but what I’m saying is that I don’t really approve of grudges, the idea, I mean.”

“This ain’t an idea.”

He nodded. “Okay.”

I peered around the edge of the post pile and studied the lay of the land. Then I caught sight of the enemy. He was down in the back yard, chewing on a big steak bone. Beulah sat a few feet away, watching him tear at the bone.

“Come here, Plato, and take a look.”

He crept over and peeked around the corner. “Good heavens! Just look at him!”

“Here’s the way I figger it. You’ll go down first and get his attention . . .”

“What!”

“. . . and I’ll move out and keep under cover. While he’s busy with you, I’ll attack and hit him on the blind side.”

“Wait a minute, Hank.”

“I hate to take a cheap shot, but I got a feeling we’re gonna need the element of surprise.”

“Hey listen, Hank, I think we’ve got a basic misunderstanding here. What I have in mind is more of an advisory role, you see the distinction? I mean, I think my talents . . . listen, man, that dog is terrible! Do you have any idea what he can do with those teeth?”

“Got a real good idea, Plato. That’s why I need a decoy.”

“Decoy, is it? You mean a sitting duck. No way am I going down there to . . .” I turned on my slow rumble of a growl. Plato swallowed and blinked his eyes. “You’re giving me no choice, is that it?”

“Yep.”

“Suicide, that’s what you’re asking. Ho, what madness!” He began marching up and down in front of me. “You’ve spent years cultivating your mind, Plato, training yourself to hunt birds. Now all we ask is that you offer yourself to the dragon, to be torn into ribbons of quivering, bleeding flesh!”

“You finished?”

He stopped. “Yes, I am finished, in every sense of the word. However, if I might offer one small suggestion, suppose we held me in reserve . . .”

“Get going.”

“Very well, all right, fine. But I must warn you: if I am maimed or disfigured, I shall hold you personally responsible.”

“Hit the road.”

“History will be your judge, Hank. Unborn generations of bird dogs will . . .”

I gave him a shove and got him out of there. I mean, he could have gone on yapping for the rest of the afternoon. I still had some work to do.

Rufus heard the commotion and looked up from his bone. He watched Plato walk down the hill, and a grin spread across his face. Beulah saw him too, and her mouth dropped open.

Rufus pushed himself up. “Ha ha! Fresh meat!”

“Listen, Rufus,” yelled Plato, “I can explain everything. Try to control yourself for just a minute and hear me out. We’ve had a little misunderstanding here but I’m convinced that we can talk it over . . .”

“Watch my bone, honey.” Rufus started dragging his paws across the ground.

“Leave him alone, Rufus, he hasn’t done anything!”

“He’s alive, and I take that as a personal insult.” He rolled his muscular shoulders and stepped out toward Plato.

The trap was set. I slipped away from the post pile and started creeping down the hill, taking cover behind shrubs and trash cans.

Plato started edging back toward the post pile. “We’re in basic agreement on most issues, Rufus, except that . . .”

“I can’t stand your face.” Rufus was stalking him now, coming closer to the spot where I was waiting.

“Right, exactly, which is basically a superficial . . .”

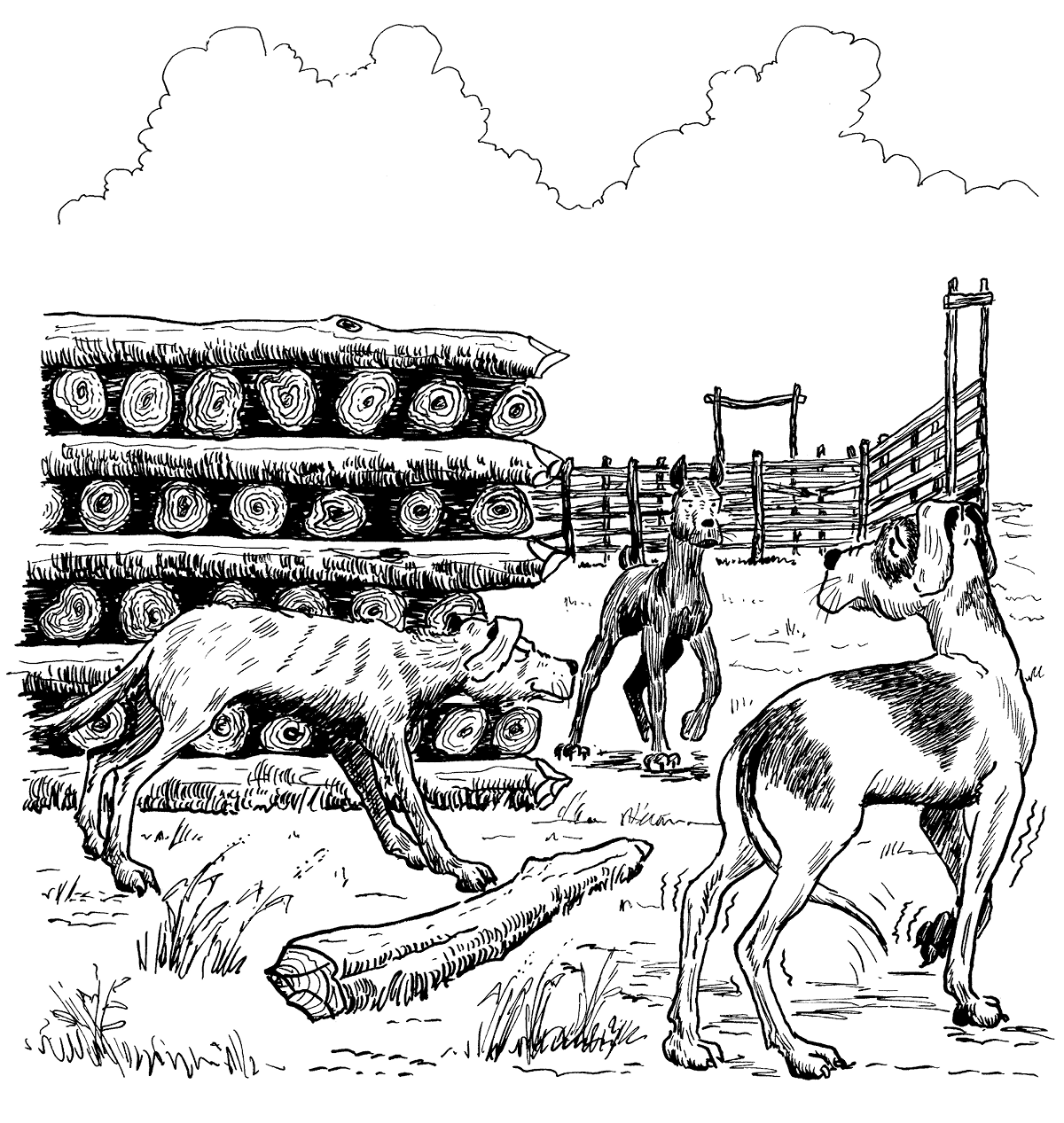

All at once Rufus sprang into a lope. The muscles in his shoulders and thighs rippled. His teeth were bared and his little eyes glistened. All the world had narrowed down to Plato and that’s all he could see.

I shot one last glance at Beulah, coiled my legs under me, and exploded out of the shrubs.

Plato stood on rubber legs and started babbling. “. . . can talk this thing out, Rufus, don’t look at me that way, I can explain, don’t tear my skin!”

There’s a kind of evil beauty about a Doberman pinscher who’s moving in for the kill, a kind of gracefulness that sparkles when he’s got murder on his mind. I caught a little glimpse of that, and then I hit him.

Old Rufus never saw me coming, never had the slightest notion that he’d wandered into my trap. I hit him with a full head of steam, which was important because I knew I’d have to stun him with a good lick or he’d come back and we don’t need to go into that.

I put a real stunner on him, got a clamp on his neck and rode him to the ground. We rolled and kicked and snarled and ripped, sent up a big cloud of dust, tore up grass and weeds, and if I’m not mistaken, I think we even broke off a huge tree.

That gives you some idea of just how terrible a battle it was: I mean, things were flying through the air, the dust got so thick I could hardly breathe, tree limbs were falling to the ground.

Well, I gnawed on one of Rufus’s ears and had things pretty muchly under control when, dern the luck, he put that same judo move on me, I should have been watching for it, got too preoccupied with the ear, and all at once he had me flat on the ground.

Then he hit right in the middle of me, kind of knocked the breath out of me.

I could hear Plato. “Sock him, Hank, knock his eye out! Give him one for me! Watch out, no, no, no, for Pete’s sake, don’t let him throw you, bad move, Hank, real poor move, you’ve got to keep the upper hand, use your teeth, man!”

“Get in here, you idiot, before he kills us all!” I managed to holler.

Just then Beulah got there. Never thought I’d need the help of a damsel in distress; did though. She jumped astraddle his back and although she wasn’t real big, she started reading him the riot act.

And then, to the surprise of heaven and earth and all God’s wonderful creation, Plato hopped in. On a good day, he might be mean enough to chew up a wet Kleenex—maybe—but at least he was there and added a little weight to the pile. I was able to get one paw free and delivered a good stroke to Rufus’s nose.

We got him on the ground and then playtime started. I was in the process of whupping the ever-living tar out of Roof-Roof when Billy came running down from the corral, yelling and waving his arms. His face was deep red.

“Hyah, get outa here! Hank, you sorry devil, go home!”

The rocks started flying. Plato and Beulah scattered for the post pile. I figgered I’d hang around for one more lick when I caught a stone in the upper back, hurt like the very dickens, and decided to evacuate.

I stepped off. “See you around, Roofie.”

Billy chunked another rock that zinged past my ear, so I loped up to the post pile.

“Don’t you ever come back here!” Billy yelled. “Just let me get my gun . . .”

I ducked behind the posts. Beulah and Plato were there. She came up to me and nuzzled my chin. “You were just great, Hank!”

“Incredible, Hank, terrific job!”

They were right, of course, but you can’t come out and say that. “Y’all didn’t do so bad yourselves.”

Beulah peeked around the corner and motioned for us to take a look. Billy was standing over his famous fighting dog and preaching him some hot gospel.

“. . . two hundred bucks and then you get yourself whipped by a ten-ninety-five, flea-bitten, sewer-dipping cowdog!” (He was referring to me, by the way.) “I oughta just take you to town and find some other sucker . . .”

Never saw old Roof look so humble. Even them high-toned ears seemed a trifle wilted.

We held a little celebration there behind the post pile, then Beulah said, “You’d better go, Hank. Billy’s mad enough to shoot you.”

“When you’re made of steel, you don’t worry about lead.”

Plato nodded. “Well put, Hank, very well put.”

Beulah only smiled—that wonderful smile of hers that said, “You’re probably one of the greatest dogs in the world and I’m about to fall helplessly in love with you but you’d better go,” or something to that effect.

Anyway, she leaned up and kissed me on the cheek, which sent ripples of joy clean out to the end of my tail. “Good-bye, Hank.”

So I loped off toward the creek and into the sunset. Just before I disappeared from sight, I stopped and gave ’em one last wave.

They waved back, which was fine and dandy, but when Plato lowered his paw, it came to rest on Beulah’s shoulder. And instead of slugging him in the teeth, as she should have done, she let it stay there.

Moral #1: Time heals some wounds but makes others worse.

Moral #2: Women are hard to figger out.

Moral #3: Women are impossible to figger out.

Moral #4: Might as well give up trying.