3

Social Problems and Social Work

3.1 Introduction

As we saw from chapter 1, state social work emerged as a response to the residual problems that were left unresolved by the universal welfare services established by the welfare state. The nature and definition of the social problems which social workers deal with have changed in important ways over the post-war period. ‘Cruelty to children’ and children being ‘sinned against’ have been replaced by child abuse; the social care of older people and that of people with disabilities have emerged as new problems in recent years, in terms both of their scale and of the kinds of solutions identified; the ‘problem of unmarried mothers’ has disappeared, replaced perhaps for a period by the ‘problem of teenage pregnancy’. These examples raise questions about how something comes to be defined as a social problem and under what circumstances. This chapter will explore these questions, in order to offer social workers a critical approach to the social problems that they are asked to address, and to enable them to assess for themselves the claims made by experts and by politicians about social problems, which are channelled through the mass media and embedded in social policies.

The chapter begins with a brief summary of debates about knowledge and explains two contrasting views about how society functions to provide a context for understanding the contested nature of social problems. We examine the general process by which some issues become labelled as social problems and others do not, and show how the identification of the source of the problem may change, as the way the problem is understood or ‘constructed’ changes. We have already seen in chapter 1 how, in the nineteenth century, the problem of poverty was seen as the consequence of individuals’ misfortune or idleness, but came to be seen in the immediate post-war period as the product of the economic cycle. These different understandings of the problem are important because they imply very different kinds of solutions and, as the previous two chapters have shown, such understandings are significantly shaped by different ideological perspectives. We outline a number of alternative theoretical perspectives on social problems to show how the adoption of a particular perspective carries with it specific implications for what the appropriate response is. The final section of the chapter offers a detailed analysis of social problems relevant to social work, starting with an examination of the emergence of child abuse as a social problem, and the ways in which its definition has changed and expanded over time. We then look at wealth (as opposed to poverty) as an issue which is generally invisible as a social problem. Looking at wealth as a social problem demonstrates how the interests of the powerful successfully promote certain issues as social problems whilst preventing others from entering our consciousness (Lukes [1974] 2005). Finally we argue that social workers have largely failed to recognize both domestic violence and the abuse of vulnerable adults as widespread social problems or to understand fully their causes and consequences, and discuss some of the possible reasons for this.

3.2 Epistemological debates

This section introduces the rest of the chapter by discussing two contrasting approaches to knowledge and research. These two approaches are founded on conflicting assumptions about the nature of the social world and therefore lead to very different proposals about the best ways to study and understand it. Philosophers have long been concerned with questions about the nature of reality, what exists (ontology) and the basis of our knowledge about the world (epistemology). How do we know what we know and can we ascertain whether what we think we know is actually true or real? These questions, which are difficult to answer in relation to the physical world, are perhaps even more difficult to answer, and more controversial, in relation to the social world. Are there different ways of understanding the world and are they all equally valid? Can we be impartial, disinterested ‘truth’ seekers when assessing contested knowledge claims or will we always be unavoidably influenced by our previous experiences and values? Such questions are not only of interest to philosophers, but also important for social workers as they intervene in social situations which have been identified as problematic in some way, in order to ameliorate them. What is the basis for identifying a situation as a problem? And what theories about the nature of individuals, the family and society underpin the intervention being made? How were those theories developed? How can we know what kinds of intervention are appropriate and are likely to produce an effective outcome? What kinds of material constitute evidence? Different theories of knowledge (epistemologies) provide different answers to these questions and lead to different kinds of actions. Here we provide a brief summary of some of the principal epistemological positions before examining their implications for understanding social problems.

A positivist, objectivist or realist epistemology asserts there is a single reality or truth ‘out there’ waiting to be discovered through empirical investigation. From within this perspective, impartial research and rigorous hypothesis testing (often using quantitative, ideally experimental methods) will reveal indisputable facts about the world and provide explanations for them. The social world is seen as no different in principle from the natural world, in terms of how it is to be investigated and understood. Within such a framework, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have privileged status in terms of the quality of the evidence they are seen to produce (see chapter 6 for more in-depth discussion of RCTs in relation to social work research). These methods tend to focus on processes and explanations at the level of the individual, and to overlook or rule out social structural factors. The types and forms of knowledge generated by other kinds of research methods are seen as less objective and therefore less valuable than the kinds of quantitative evidence which experimental and quasiexperimental methods produce. Although there are fierce debates within social work about what forms of knowledge should be prioritized, this kind of positivist epistemology is currently in ascendance. Explanations of social problems suggesting apolitical, often behavioural, ways of dealing with either the individual ‘causes’ or ‘casualties’ of social problems correspondingly take precedence.

An interpretivist, subjectivist or social constructionist epistemology, conversely, asserts there are many different ways of understanding the world, all potentially equally valid. This approach focuses on the meanings of events, practices and relationships and our interpretations of what is real or unreal, true and false, right or wrong, and tends to use qualitative methods of research. Constructionists reject claims that there is one definitive answer to every question or one objective reality ‘out there’. They assert that even universally accepted facts are channelled through a simplified common-sense framework (or set of assumptions) influenced by our past and present understandings and experiences. This framework only becomes apparent when it is disrupted or challenged in some way. Garfinkel (1967), an ethnomethodologist, for example, asked his students to disrupt convention and behave in their parents’ homes as if they were paying lodgers and barter for goods at supermarket checkouts and then to note the bewildered, hostile responses they had evoked in order to demonstrate just how important shared interpretations and norms are.

Both positivist and constructionist epistemologies are, however, ‘ideal types’, in that they are rarely adopted in their purest forms. Most positivists today concur with Popper’s notion of ‘uncertain’ or revisable truth in that all theories have the potential to be falsified, although those surviving over long periods of time may be more plausible. Most constructionists would also accept that pure versions of social constructionism or total relativity are problematic. Few people would jump out of an aeroplane to test out the ‘socially constructed’ law of gravity. The general public, however, probably still believe, it is possible to discover irrefutable truths, although many remain bemused that expert scientific exhortations in relation to what we should eat, drink or do to attain optimum health are constantly revised as new studies gain media attention.

3.3 Consensus and conflict theories of society

To understand this chapter fully, it is necessary not only to comprehend different views about epistemology but also to be aware that sociologists hold different beliefs about the nature of society, how it operates and whom it benefits. A consensus perspective assumes a generally optimistic view of society as functioning harmoniously for the most part and able rapidly to restore equilibrium when problems occur. From the opposing perspective, society is characterized by ongoing inequality and differential interests which lead to conflict and competition.

Consensus or order theories of society are best exemplified by the structuralfunctionalist approach dominant in sociology in the mid twentieth century. This uses metaphors of society as an organism or a machine comprised of various inter-related organs or parts, each of which contributes to its smooth running, with little acknowledgement of conflicts between the different parts that make up the whole. However, it attempts to account for the development of social institutions solely by referring to their effects, which constitutes a circular argument. Even ‘deviant’ behaviour is deemed functional because social exclusion, stigmatization or imprisonment act as a warning to potential future transgressors. Consensus theories therefore have difficulty in accounting for social change. If institutions all contribute in an organic way to the smooth running of society, how and why does change occur?

By contrast, conflict theories see society as characterized by conflicting interests, with elite groups having the power, knowledge and resources to reproduce their own privilege and control subordinate groups through ideology (influencing their desires, thoughts and feelings) and, if necessary, through coercion. From a Marxist perspective, for example, the ruling class uses its power to perpetuate its privileged position within capitalist society through the labour of the working class, who have to sell their labour power in order to survive. Feminists argue that we live in a patriarchal society where men have more power and receive the lion’s share of resources, including earning more by doing jobs that are more socially valued than women’s and doing less domestic and childcare work.

These contrasting theoretical perspectives on the nature of society have rather different implications for how social problems are understood. Differences in epistemological perspectives mean that there are also conflicting ideas on how social problems can be investigated and on what constitutes evidence. It is clear therefore that there is scope for considerable disagreement about what constitutes a social problem and what kinds of policies are likely to be effective in addressing them. Social workers who are called upon to intervene in a wide range of social problems need to have some understanding of these debates in order to be able to exercise their own critical judgement.

3.4 What are social problems?

It may seem obvious what a social problem is. Many examples spring to mind – violent crime, child abuse, homelessness, the war on drugs, asylum seekers, or the care of an ageing population. But in trying to explain why these are social problems, define them more closely and identify whom they affect and what their causes and solutions might be, it becomes clear that agreement about social problems is not so straightforward. We might even start vehemently disagreeing with each other. We might argue about whether spanking children is child abuse or just necessary discipline for the good of the child, how widespread it is and therefore whether it is a social problem; or perhaps whether asylum seekers are deserving victims fleeing oppressive regimes or, alternatively, duplicitous economic migrants swamping our country and stealing our jobs. Such arguments hinge upon our understanding of society and how we evaluate the information that we are presented with by politicians, the mass media and other sources.

At a basic level, an issue becomes labelled as a social problem when: (i) it attracts the attention of a particular society during a specific time period; (ii) it potentially impacts negatively on significant numbers of people (or smaller numbers of powerful people); and (iii) there is an acceptance that something needs to be and can be done about it. However, what is perceived as a social problem may change as society and social attitudes change. Unmarried motherhood was seen as a significant social problem in the nineteenth and most of the twentieth century but no longer is, because of changes both in behaviour (many more women choosing to have a child without marrying) and in social attitudes (a decline in the power of the Church and in the practice of Christianity). Few in Western societies view witchcraft as a social problem anymore, although it was seen as such in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, with increasing numbers of people coming to live in England from societies where there is a belief in witchcraft, it has re-emerged as an issue in child abuse cases, with some children in some minority communities at particular risk of being labelled as witches and maltreated. Furthermore, what is included within the scope of a particular social problem may change. Child abuse and domestic violence or abuse are two contemporary social problems whose definitions have broadened considerably over time. Some social problems, such as ‘the problem of youth’, may disappear and then re-emerge at a different time period but be presented differently on each occasion: from Teddy Boys in the 1950s, Mods and Rockers in the 1960s, Punks in the 1970s through to Chavs and Hoodies in the 2000s. The common element is the depiction of working-class young men as a threat to the accepted social order, despite changes in the ways in which they present themselves (Pearson 1975).

Some social problems come to be identified as such because people ‘have’ problems, but another route involves certain people themselves being constituted as the problem, although the distinction is not always clear-cut. Mentally ill people might, for example, be seen as a social problem because of individual misfortune and represented as requiring help and support. Alternatively, in the rare cases where a mentally ill person kills someone, they often become reconstructed as a threatening social problem, requiring greater surveillance and compulsory treatment. Homeless people too might be constructed as the victims of poverty, mental illness, misfortune and inadequate housing provision, or alternatively seen as culpable because of feckless behaviour or drug addiction and represented as menacing eyesores on our streets. Hence, the same people might be seen as victims, villains or perhaps nuisances at different times, or even simultaneously. When people, such as abused children or elderly or disabled people, are seen as having problems not of their making, the appeal is often to a sense of social justice. Conversely, where people such as drug users or teenage gang members are seen to be the problem because they contravene social norms, the issue often becomes reconstructed as one of social (dis)order, whether social order is achieved through rehabilitation or criminalization and incarceration.

The policies proposed to address social problems will depend on how those problems are explained. The abuse and neglect of vulnerable people in residential institutions or hospitals, for example, tends to be explained as the result of the incompetence or negligence of individual ‘bad apples’ (Stanley et al. 1999); an alternative explanation might look at the consequences, for staff training, pay and conditions, of services being delivered by private providers motivated by profit. These alternative explanations have rather different policy implications. Contemporary understandings of social problems are often informed by earlier perspectives. The next section provides a historical outline of different perspectives on social problems, showing how they complement or conflict, build upon or mutually influence, each other.

3.5 Early perspectives on social problems

Pathology, disorganization and value conflict

The social pathology perspective was the dominant view on social problems from the 1890s to the 1940s and located social problems mostly within defective individuals, who were seen as containable through re-education and re-socialization or through selective restriction of fertility (eugenics). Welshman (1999), for example, shows how ideas about specific families as ‘social problems’ in England in the 1920s and 1930s centred around claims about inherited mental deficiency, laziness and immorality caused by inbreeding, with solutions such as enforced sterilization advocated. The association of eugenics with Nazism meant that this became increasingly unacceptable as a policy approach in Britain in the post-war period. As social work emerged as an embryonic profession in the late 1940s, it pioneered casework for problem families. This emphasized re-educating families and providing them with financial and practical support, but this more humane approach remained based on a view of such families as deficient in some way. An alternative perspective, the social disorganization approach, emerged after the First World War. This attributed increasing alcoholism, crime and mental illness to the stresses and tensions individuals suffered during a period of significant social change. Both these perspectives were based on a realist epistemology and consensus view of society, with the proposed remedies focused on changing the individual rather than society (Manning 1987).

In the 1950s a contrasting value conflict perspective emerged, based on the work of the sociologist C. Wright Mills. He argued that certain groups or alliances – for example the ‘power elite’ consisting of ‘big business’, military leaders and politicians – had much greater resources not only for defining certain issues as social problems but for suggesting causes and pursuing solutions. Mills proposed a conflict view of society and challenged positivism by arguing that certain groups had more power than others to represent ‘the truth’. In opposition to this conflict perspective, the social pathology/disorganization hypotheses re-emerged, albeit in a different form: the deviant perspective. Based on a consensus view of society, it suggested that certain subversions of socially accepted norms and rules (such as homosexuality, drug taking or theft) threatened overall societal unity. Transgressors therefore needed to be identified and neutralized before they constituted a real social problem (Rubington and Weinberg 2003).

Labelling theory, moral panics and critical perspectives

From the 1960s the value conflict perspective was used in labelling or societal reaction theory which proposed that deviance was not inherent in what people did, but was based on reactions to their behaviour, with those in positions of greatest power able to exert most influence in determining what was labelled a social problem (Becker 1963; Lemert 1972). People in powerful and privileged institutional positions, such as professional experts or politicians, are able to attach negative labels to relatively powerless groups, and are assisted in this by the media, which reproduce the definitions of those who have power and access to journalists. An interesting study by Chambliss (cited in Hechter and Horne 2003) illustrates the power of labelling.

In his study in Chicago, Chambliss identified two groups of high school students, both of which had a tendency to drink, steal, break curfews and vandalize property. The ‘Saints’ were boys who overall had good grades, came from stable middle-class households, and were careful not to be caught by the police. The ‘Roughnecks’ were boys from poorer and less stable households. They were more likely to be hostile in confrontations with the police and were not as careful to avoid being caught. The boys in the ‘Roughneck’ group were labelled as deviants. The ‘Saints’, even though they committed similar crimes, were not labelled because they were polite when caught and were from a higher social class. The police consistently took legal action when dealing with the ‘Roughnecks’. The ‘Saints’ were treated far more leniently and were never prosecuted.

The credibility of the labeller and of the labelled persuades the audience of the seriousness of the behaviour and appropriate responses. The labelling school also distinguished between primary deviance, based on the initial labelling of a behaviour as deviant, and secondary deviance, when a person starts to behave and identify with the label attached to them by society. For example, someone labelled as a criminal for a minor infringement of the law such as shoplifting, may be driven to increasingly serious crimes – burglary or robbery – because of the consequences of being labelled a criminal, such as difficulties in getting a job.

The concept of a moral panic also emerged in the UK from the labelling perspective (Young 1971; Cohen 1972, 2002). Cohen showed how the threat posed by a normally powerless group could be artificially intensified, resulting in them being represented as a social problem. He summarized the process in this way:

A condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; the moral barricades are manned by bishops, politicians and other right-thinking people; socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnoses or solutions; ways of coping are evolved or (more often) resorted to; the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates or becomes more visible. (Cohen 1972: 9)

Cohen’s study of Mods and Rockers (working-class youth cultures with divergent and distinctive dress styles and musical tastes) in the 1960s showed how, through media amplification of the threat they represented (if, indeed, there was any – the two groups had a few minor scuffles in seaside towns), they became labelled as folk devils, symbolizing a wider underlying social malaise or problem, i.e. degenerate youth and family breakdown. Cohen argues that, because the Mods and Rockers were portrayed as violent feuding gangs, they might have felt obliged to play out their roles, and that, as the police presence increased in response to media concern, this might also have triggered violence or uncovered minor feuding which otherwise would have gone unnoticed. Cohen therefore argues that a moral panic of this kind may actually create or aggravate a social problem, rather than simply reporting an existing one.

Gove (1975) criticized the labelling perspective, arguing that people were generally categorized as mentally ill, for example, because of enduring, seriously disturbed behaviour, not because of the ‘sticky’ application of a mere label. However, Rosenhan (1973) demonstrated the power of labelling when he and seven associates got themselves admitted to psychiatric hospitals in the USA without difficulty, on the pretext they were hearing voices (a symptom associated with a diagnosis of schizophrenia) despite displaying no other symptoms. After admission, all the pseudo-patients claimed they were no longer hearing voices and behaved ‘normally’, but had great difficulty in getting themselves discharged and shedding their ‘label’. All their ‘normal’ actions were pathologized by the staff because of their diagnosis of schizophrenia, although other inpatients paradoxically discerned that they were not ‘mad’. The labelling perspective, unlike the moral panic thesis linked to it, focuses primarily on the process and consequences of labelling rather than being concerned with the bigger question of how social problems are constructed. Therefore, although the theory illuminates how labelling can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy and highlights the differential influence of those in positions of power, it does not offer a full theoretical account of social problems.

A critical perspective emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. This built on the value conflict and labelling / moral panic perspectives from a Marxist viewpoint, influenced also by the social movements of the period. The British criminologists Taylor et al. (1973) argued that much crime is caused by the material inequalities created and sustained by capitalism, and that some criminal activity represents active resistance to capitalism. Stuart Hall et al. (1978) drew on Cohen’s ideas about moral panics to look at street crime and argued that capitalism used such moral panics as the basis for repression. Hall showed how the term ‘mugging’ was imported from America, expressing wider anxieties about working-class Black youth. The media reported that muggings had increased by 129 per cent between August 1972 and August 1973. This statistic had no valid basis because mugging was not a category in the recorded crime statistics, but it led to the identification of ‘muggers’ as sinister young Black men. This reinforced racist fears and prejudices and influenced calls for predominantly Black neighbourhoods to be more vigilantly policed. Folk devils and their supporters do sometimes fight back today, using social media and the internet, but their depiction as ‘unambiguously unfavourable symbols’ (Cohen 1972: 46) means their resistances are often neutralized and moral panic becomes linked to moral regulation in terms of reinforcing dominant societal discourses (Hier 2011). The perceived proximity of the threat (whether people feel it is likely to happen to them) and discourses of risk also appear to be important preconditions for a successful moral panic.

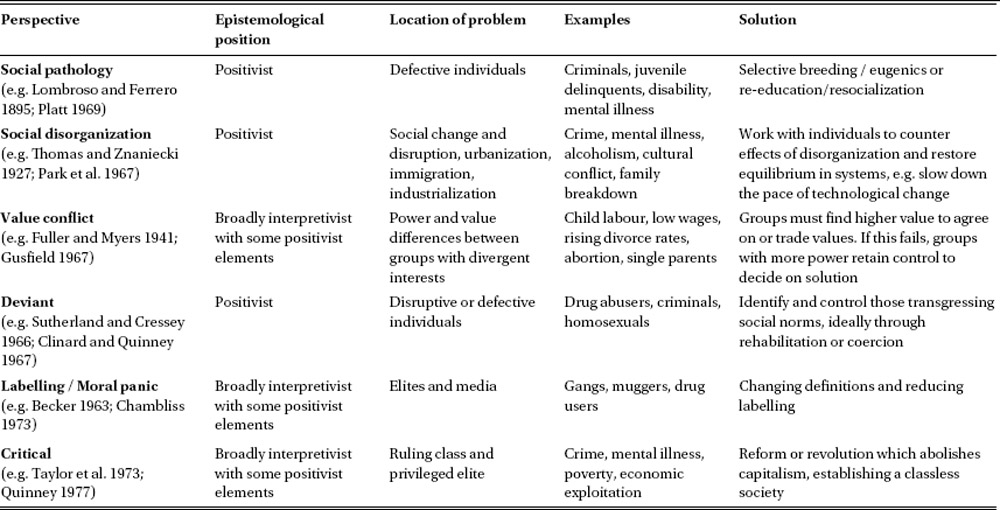

The six perspectives discussed illustrate how understandings of social problems have evolved and how they draw on different epistemological and political perspectives. Table 3.1, adapted from Rubington and Weinberg (2003), summarizes these different perspectives and some of the key authors associated with each.

These different analyses of social problems are founded on different approaches to knowledge and society, briefly explained at the beginning of this chapter. The early social pathology, disorganization and deviance approaches were unequivocally positivist and ‘apolitical’ in the sense that they assumed that the identification of social problems was uncontroversial, reflecting a consensus view of society. They saw the problems as located in ‘individuals’, whether this was because of inherited defects, faulty socialization or rapidly changing socio-economic conditions. The solution lay in controlling or reforming the individual. For biological determinists there was no real cure for those born bad, aside from genetic engineering. More humanitarian individuals argued individual correction was possible for both environmental and genetic causes, so that juvenile delinquents, for example, had to be ‘saved’ from pursuing a criminal career (Platt 1969). The value conflict perspective recognized differential interests and more powerful groups’ ability to get their definitions of and solutions to social problems legitimated. The labelling perspective paid specific attention to: (i) the processes through which people become labelled as deviants or members of ‘social problem groups’; (ii) who had the power to attach such labels successfully; and (iii) what the potential consequences might be. Labelling and value conflict perspectives flagged up, but did not fully develop, the significance of different interest groups in society and did not advocate an overtly political solution. Critical perspectives, although unequivocally allied with a conflict, often Marxist, view of society, were mixed in terms of their epistemological position. On the one hand, they presented an objectivist viewpoint in claiming their Marxist interpretation of society was correct, but they also argued a transition was possible, from an ideologically conditioned acceptance of the status quo to the proletariat recognizing and questioning their oppressed position and envisaging the possibilities for a different society.

Table 3.1 Alternative theoretical perspectives on social problems

Source: adapted from Rubington and Weinberg (2003).

Changes in how poverty has been understood as a social problem illustrate the shift from the individualized explanations of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, to explanations in the mid twentieth century that give a role to economic and social structures. Recent policies have returned to viewing poverty as the result of individual failings, with the solution lying in greater individual efforts to engage in paid work. This brings us on to the most recent perspective on social problems, the social constructionist perspective, which in modified form offers social workers a framework for deconstructing and understanding social problems.

3.6 A social constructionist approach to social problems

Social constructionism is a perspective which argues that our interpretation of issues and events, and the meanings that we attach to them, shape our actions and beliefs. We might assume a man, bending seemingly intimately over a partially clothed supine woman, is the precursor for a heterosexual couple about to engage in sexual intercourse, but it could be a doctor examining a pregnant woman. However, an interpretation only becomes a solidified social construction when it is ‘bought into’ by many people, accepted as a self-evident fact and incorporated into institutional and social practices (Berger and Luckmann 1967). Social constructionism is often presented as the counterpoint to essentialist or reductionist viewpoints which tend to explain individual or group characteristics by reference to biology or nature (‘men are naturally more logical than women’, ‘she’s less confident because she’s a girl’) with little acknowledgement of the interactions between biology and culture. Widespread acceptance of the belief that gender differences are based in biology, and that women and men are therefore ‘naturally’ very different in their personalities and abilities, with male attributes being more socially valued (Lorber 2010), has supported women’s economic and social subordination. A social constructionist approach to social problems suggests that the extent to which a particular issue is perceived as problematic, as well as the kind of problem it is understood to be, is a function of social interaction, understanding and interpretation. This runs counter to early social pathology perspectives which often offered purely biological explanations of people’s behaviour: ‘Social problems are [therefore] ambiguous situations that can be viewed in different ways by different people and that are defined as troubling by some people’ (Best and Harris 2012: 3). Social constructionism builds on the value conflict and labelling perspectives of the late 1970s but goes further, ultimately arguing ‘subjective definitions not objective conditions [are] the “source” of social problems and the proper object of study’ (Rubington and Weinberg 2003: 283).

This does not mean that all social problems ‘claims’ should be given equal weight. Joel Best (1995) advocates contextual social constructionism, suggesting both the claims-making processes and claims about the ‘objective’ situation should be critically analysed within their socio-historical context. Loseke (2010: 7) asserts that social problems are about both ‘objective conditions and people (things and people that exist in the physical world) and they are about subjective definitions (how we understand the world and the people in it)’. She shows that ‘objective’ indicators do not necessarily lead to an issue being recognized as a social problem, and conversely something may be identified as a social problem when that has little basis in reality. ‘Stranger danger’, the risk strangers pose to children in terms of sexual abuse and other harm, was repeatedly flagged up as a ‘real’ social problem between the 1960s and the new millennium but, according to Loseke, has never ‘objectively’ constituted one, as most children are harmed by those they know. Similarly, teenage pregnancy has repeatedly been identified by politicians and others as a social problem in the UK. Policy has consequently focused on reducing conceptions among under-eighteens, on the assumption that teenage pregnancies occur because of ignorance and lead to economic dependence and poor outcomes for children. However, research has shown that many pregnancies, if not actively chosen, are certainly not unwanted, can be empowering and do not inevitably lead to poor outcomes (Duncan 2007; Middleton 2011). Although social workers may be involved disproportionately with young people, such as those formerly in care, who struggle with their pregnancies and their children, refusing to see teenage pregnancy as unequivocally problematic could help social workers re-evaluate and respond to it in a more positive way.

Loseke’s framework shows not only how social problems are constructed but also which claims are most likely to be successful. Her framework therefore helps the social work practitioner to evaluate the validity of the claims and proposed solutions. Like earlier theorists, Loseke proposes a hierarchy of credibility of claims makers, with scientists and other experts, politicians and members of elite groups having maximum credibility, while powerless groups such as children and elderly people have the least credibility, if they manage to publicize their views at all. If the target audience is an elite group, fewer people need to be persuaded than if it is the general public. Loseke argues we are persuaded – or not – that something is credible, important and a real social problem by a package of claims. Verbal claims might involve statistics, personal accounts or research findings. Visual claims involve a pictorial depiction, such as a starving child or injured elderly person, and evoke horror, fear, sympathy or even hatred. Behavioural claims generally involve activism, such as Black people in the USA protesting against racial segregation in the 1950s by sitting in Whitedesignated areas on public transport.

Packages of claims are most successful when they convey a simple message and focus on the suffering of victims rather than on villains. Many service users, however, are difficult to categorize as ‘pure’ victims – for example, abused and neglected adolescent boys who commit crimes, or parents who abuse their children. The ‘subjects of social suffering may not easily elicit compassion if they do not present themselves as innocent victims, but as aggressive, resentful or suspicious people whose hurt and loss is directed at others’ (Frost and Hoggett 2008: 453). If villains are to be effectively presented as social problems they must be pathologized in some way that suggests possible rehabilitation. Alternatively, they need to be represented as dangerous ‘outsiders’. Hence the public reluctance to accept that sexual abuse of children is most frequently perpetrated by immediate family members – ordinary ‘family men’ – rather than by strangers, who are more easily seen as ‘other’.

Messages about social problems must also be comprehensible to their audience. Domain expansion is one strategy adopted to keep a problem in the public eye and aid understanding by including a new issue under an already familiar and publicly understood label. New social problems are ‘piggybacked’ onto old problems which are thereby broadened. Child abuse, for example, now includes parental smoking. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been extended from being a specific short-term disorder suffered by psychologically shell-shocked war veterans to include a much wider range of circumstances (Loseke 2010). It is now seen as potentially induced by situations varying from witnessing a single road traffic accident to the experience of serial abuse in childhood. Social problem claims are often particularly effective when issues are personalized and the audience can identify with the victims and see how they themselves could be affected. When people evaluate social problem claims, they also draw on their own experiences as ‘practical actors’, and on commonly accepted cultural themes, such as the fear of crime.

In her book, Loseke devotes an entire chapter to what she calls the ‘troubled person industry’. This refers to the various organizations and professionals who support, rehabilitate or punish the victims or villains who are the subjects of most social problem claims. Their existence suggests the success of the claims-making process, at least to some extent. Some of these professionals (including social workers) possess considerable power to deprive individuals of their liberty, or give them access to important services or resources. Victim status leads to diminished power, and victims are expected to behave in a passive way to retain sympathy and support, while those offering sympathy or support, such as professionals, gain status. We will return to these cultural feeling rules later in this chapter in the context of a discussion of adult safeguarding, which involves the protection of vulnerable adults.

3.7 Social work and social problems

Although little is known about how social workers understand social problems, they have historically tended to perceive service users in two main ways: (i) as deviant or damaged threats to society requiring control; or (ii) as casualties of a ‘sick’ society or struggling individuals who require support and therapy. A minority of social workers adopt a third, more radical position, which locates the root cause of many clients’ problems within an unjust social order and advocates substantial social change (Pearson 1975; Payne 1996). The first two positions reflect the early pathology, deviance and social disorganization approaches, with only the third showing some awareness of value conflicts and inequalities. There is some indirect evidence of the persistence of the deviance and pathology perspectives. A small-scale study in one English university found that most social work applicants, who wrote about social problems and their possible causes and solutions as part of a literacy entry test, attributed them predominantly to individuals’ anti-social behaviour (Gilligan 2007). Although these were social work applicants, not students or trained practitioners, this study underlines the importance of adopting a more critical perspective in order not to compound the significant disadvantage most social work clients already experience as a result of prejudice, inequality or misinformation.

Many contemporary social workers, whilst acknowledging the importance of the care and control elements of their occupation, may hold more nuanced views about their service users and be able to work sensitively with tensions and contradictions/ambiguities. However, as we demonstrate in the examples that follow, there remain problems with how social workers understand and respond to social problems and the social policies linked to them. We offer a critical perspective on four issues directly relevant to social workers’ engagement with social problems:

- the emergence of child abuse as a social problem and its changing definition

- wealth as an example of an issue which has not been recognized as a social problem

- the limitations of social work responses to domestic abuse when children and child abuse are involved

- the lack of recognition that the abuse of vulnerable adults is a widespread social problem requiring a collective societal response.

Child abuse as a changing social problem

Child abuse emerged as ‘the battered child syndrome’ in the 1960s when some paediatricians successfully attracted media attention to the fact that the X-rays of many children who suffered head injuries revealed healed or healing limb fractures (Kempe 1968). Because ‘the battered child’ was a new concept (like mugging), it was not possible to ascertain whether the number or severity of parents beating their children had increased and therefore a new social problem had come into existence, or whether X-rays had merely revealed something which had been occurring for a long time (Hacking 1991). Since the ‘discovery’ of the problem in the 1960s, the term ‘child abuse’ has increasingly been used to refer to a much wider range of practices than physical abuse, illustrating domain expansion (Loseke 2010).

The contemporary definition of child abuse encompasses a wide variety of contexts, perpetrators and types of behaviour towards children. Child abuse can be perpetrated by adults or children, acting as individuals or in groups. It may occur as organizational or institutional abuse, for example in schools or residential children’s homes, and involve physical, psychological or sexual abuse by individuals or groups. Alternatively, abuse may be the result of the organization’s procedures or modus operandi which are directly disrespectful and abusive to children or have unintended abusive consequences. The boundaries of what constitutes child abuse are hard to define. Is physical punishment child abuse at every level, including one ‘mild’ smack, even if the law says otherwise, or only if it results in severe injuries or is repeated? Is a fourteen-year-old having consensual and non-pressurized sexual intercourse with a seventeen-year-old child abuse? Could allowing children to live in crime-ravaged and poverty-stricken areas be constituted as societal child abuse in an affluent nation? Are parents who ‘hothouse’ their children academically or systematically groom them to be child ‘stars’ or sporting champions abusers?

Multiple definitions, different political agendas and professional interests mean that there is a lack of agreement about both causes and solutions (e.g. Green 2006). The interests of the medical profession are apparent in the 1960s ‘discovery’ of physical child abuse, as are those of religious institutions in their denial of widespread sexual abuse of children within their care. Social workers and doctors are frequently vilified for being insufficiently vigilant (as occurred in the cases of Victoria Climbié and Peter Connelly), or alternatively overzealous, as occurred in Cleveland, England, in 1987, when over 100 children were taken into care due to concerns about sexual abuse. The doctors and social workers had very serious concerns that these children had been sexually abused and deployed a ‘new’ diagnostic procedure – anal dilation (previously used to investigate adult anal rape) – to try and confirm or dismiss these concerns. Some of the men accused of abuse, with the support of a very vocal MP, orchestrated media coverage which was more concerned with fighting state intervention into the private sphere of the patriarchal family (arguing that ordinary fathers could not possibly have committed such heinous crimes in such large numbers), than with the protection of the children involved (Campbell 1988; Hacking 1991). The social workers and doctors were publicly demonized and the needs of the children became lost in the media coverage of the ‘scandal’, many being returned home. Here we clearly see how social problem claims are less successful (Loseke 2010) when the ‘villains’ cannot be categorized as marginalized outsiders, and that responses to child abuse as a social problem are not always benevolent.

When child abuse was first ‘discovered’ in the 1960s, there was disagreement about whether it should be understood as a criminal act or a medical disorder. Paediatricians tended to see it as the expression of individual pathology and this medicalization served their professional interests, as demand for their work declined with the advent of vaccination and improved environmental conditions. The gradual acceptance that child sexual abuse is common and predominantly perpetrated by known males – often family members, friends or neighbours – rather than demonic strangers, calls for a different explanation from ‘individual pathology’. Beckett’s (1996) analysis of media accounts of child abuse in the USA over four different fiveyear periods revealed different social problem claimants with contradictory views about causes and potential solutions at different times. Between 1980 and 1984, professionals working in child abuse dominated the discussion, arguing child abuse was a widespread problem that society could no longer deny, focusing on the suffering children endured. Between 1985 and 1990 a backlash occurred, with the assertion that many allegations were false, that children could fabricate abuse, misinterpret situations or be manipulated into lying – for example, in relation to child custody cases. Doubt was also cast upon professionals’ ability to diagnose and treat abuse and there were suggestions their techniques were leading and unreliable. Between 1991 and 1994, the plight of adult abuse survivors, often celebrities, dominated news reporting, echoing the early 1980–4 period. However, this focus was short-lived and there was again a backlash which focused upon potentially false allegations, including false memory syndrome – a synonym for professionals implanting false abuse memories in the minds of suggestible, vulnerable individuals.

Some commentators suggest social problem claims about child abuse and its causes and solutions are less about the child and more about state power and controlling ‘deviant’ and threatening families (Donzelot 1980; Dingwall et al. 1984) whilst simultaneously denying sufficient financial support to poor families and discouraging them from protesting by inducing fear: ‘A mild version of this observation is that the child abuse movement serves to conceal the decline in social support for children. The strong version says that child abuse legislation is a cheaper and more effective form of control of deviant families than welfare (Hacking 1991: 262). This comment may help us to understand the current situation in the UK. Rising inequality, compounded by a narrow focus on high-risk child protection social work with mostly poor families, undermines social workers’ ability to build strong partnerships with children and families, which are humane, preventative and community-orientated (Featherstone et al. 2012, 2013). Child and family social work has been influenced by recurrent moral panics about children killed by their carers, and some argue that most child protection policy does more harm than good (Lonne et al. 2009). Clapton et al. (2013: 213) argue, echoing Cohen (2002: xxxv), that one important consequence of moral panics is that we have been ‘taking some things too seriously and others not seriously enough’. Perhaps this is this case with the concern about high-risk families taking precedence over adequate financial support and long-term preventive work with families. The current narrow social work emphasis on detecting child abuse may have adverse consequences for poor families, particularly female-headed families, who tend to be placed under surveillance and demonized (Wrennall 2010), whilst little attention is paid to the injustices and multiple disadvantages they routinely suffer (Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) 2012). Horwath’s (2011) small-scale study involving sixty-two social work practitioners and managers identified an over-riding preoccupation with risk management, strict timescales and a form-filling culture. This encouraged a siege mentality, separated ‘need’ from risk of harm, and marginalized adolescents, disabled, asylum-seeker and refugee children, and those from different faiths and higher socio-economic groups. Parton’s (2011) analysis of child protection and safeguarding work from the 1980s to 2008 also found that moral panics, alongside bureaucracy, managerialism and time-consuming electronic (ICT) systems (examined further in chapter 5), led to forensic forms of social work concerned only with identifying and intervening in ‘high-risk’ cases. Although the Every Child Matters reforms from 2004 onwards superficially offered a broader emphasis on safeguarding, which promoted the general health and well-being of all children, not just those deemed to be ‘in need’ or ‘at risk’, in 2008, after the murder of 17–month-old Peter Connelly, social workers, managers and doctors associated with the case were vilified and the pendulum swung fully back to focusing on the heavy end of ‘at-risk’ cases. Wrennall (2010: 1477) goes further than most in arguing that the rhetoric of child protection enables hard-won civil and human rights to be bypassed, disguises surveillance and disarms opposition, thereby allowing social workers to penetrate ‘where orthodox policing can no longer go’, whilst simultaneously concealing wider economic and political interests.

The Rotherham grooming scandal, examined by the Jay Report (2014), showed how 1,400 vulnerable children, predominantly girls, often from care backgrounds, had been groomed and repeatedly sexually assaulted by mostly Asian gangs in Rotherham between 1987 and 2013. Little effective action was taken by police and the council, who often viewed these abused children as errant teenagers and were fearful of being accused of racism or religious prejudice. Since the media scandal, a number of high-ranking professionals have been dismissed or pressured into resigning, but few of the men reported to the police by victims have been arrested, and support services and help with compensation were limited (Ahmed 2014). The absence of a more comprehensive response to the problems revealed raises questions about how seriously the issue has been taken by central and local government.

So what might social workers take from an in-depth understanding of the differing ways child abuse has been constructed as a social problem and the changing policy responses to it? They should understand that child abuse is not a fixed category and media or governmental representations of it are not always ‘neutral’ or concerned with the child’s needs or well-being. Social workers therefore need to evaluate social problem claims about child abuse critically and decide how they might respond as individuals or groups of social workers. Although the boundaries of what constitutes child abuse have changed and are contested, and responses to it have been variable and have not always benefited the children concerned, it is generally accepted as something that is wrong and should not occur. However, the next social problem to be examined, wealth, has rarely been conceptualized as such, presumably because this would be to the detriment of wealthy elites who have considerable power to influence what is defined as a social problem.

Wealth as a social problem?

Social workers deal predominantly with people who are poor and who are often depicted as causing social problems (the social pathology approach), intervening in the lives of people who are presented both as requiring support and as possessing the potential to cause problems to others – such as juvenile delinquents or poor mentally ill people in the community. Poor families and individuals have been referred to in different ways over time (‘the residuum’ in the nineteenth century, ‘the underclass’ in the 1990s, ‘troubled families’ in the present century), but these different labels conceal a common perception of the problem as located in these individuals rather than there being some other cause. Questions about the causes of poverty and whose responsibility it is to resolve it therefore become diverted into a discussion about how to ‘save’ abused or ‘at-risk’ children or control deviant or threatening groups.

A number of recent studies have put the problem of poverty in a new perspective by examining whether the rich deserve their wealth and whether the same standards are applied to rich and poor (Rowlingson and Connor 2011; Rowlingson and McKay 2012). It is hard to see how the enormous salaries of bankers and financiers across Western nations are justified when their actions in the last decade have bankrupted financial institutions and threatened the stability of capitalism. The cost to the state of rescuing these institutions has been met, in the UK, by cuts to other areas of government spending, affecting the poorest most. Even disregarding difficult debates about what constitutes desert in terms of hard work, productivity or value to society, many of the rich acquire their wealth not through work, effort or merit (however defined) but through inheritance.

Social class and power have a significant impact on how social problems are defined and understood. For example, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, negative equity – houses selling for significantly less than their purchase price – was identified as a social problem affecting significant numbers of home owners (Open University 2011). At the same time, rising rents and poor-quality rented housing affecting similar numbers of people were not recognized as a social problem that required some kind of government response; rather, the difficulties faced by those in rented accommodation were seen as private, individual troubles. The repercussions of the withdrawal of the state from housing provision, and the sale of council housing, were even more apparent three decades later (Hodkinson et al. 2013). The Coalition government continued to put resources into helping people into home ownership, through a variety of mortgage assistance schemes, but did little to support the building of more social housing or to control rents in the private sector. Landlord repossessions rose, and in 2012 there were over 5 million people on waiting lists for social housing (Hodkinson et al. 2013), yet because these issues affected those on lower incomes, who did not constitute a social threat at the time, and could not be depicted as pitiful victims, this crisis was not represented as a social problem.

The final two sections examine two social work issues where arguably there has been a misrecognition of a social problem: domestic violence and mother blaming in the context of child protection, and the abuse of vulnerable adults.

Domestic violence and ‘mother blaming’

Domestic violence (DV) or domestic abuse involves one partner or ex-partner, or other family member, subjecting another to physical, psychological, sexual or financial abuse or humiliation or combined forms of these (Home Office 2013). It is intermittently recognized as a social problem and has been subject to domain expansion because it originally referred only to physical interpersonal violence but now incorporates other forms of violence and subjugation. DV is now defined in England as a child protection/safeguarding issue. The Adoption and Children Act 2002 extended the term ‘child abuse’ to include the harm children may suffer from witnessing others being abused, another example of domain expansion. Although the situation of children witnessing abuse (but not having abuse directly perpetrated upon them) is now constituted as a form of indirect child abuse, children themselves are additionally at greater risk of being directly abused or neglected in families where one adult is subjecting another to violence. This section is principally concerned with children who witness a father or father figure subjecting their mother to domestic abuse and are simultaneously directly at risk from or subject to harm from the same perpetrator. Domestic abuse is not confined to heterosexual relationships and women are not always the victims. However, its frequency and severity are much greater in relation to heterosexual relationships where men are the perpetrators and women the victims. Here we examine how adequately DV has been recognized as a gendered social problem by social workers.

The British Crime Survey, a nationally representative survey of over 23,000 men and women, revealed DV as a widespread, gendered social problem. Men are the principal perpetrators, if living in fear, frequency of assaults and physical harm are taken as the key indicators (Walby and Allen 2004). Humphreys and Absler’s (2011) content analysis of thirteen publications from the USA, Australia, Ireland and England found that there was little support for women experiencing DV whose children were also being harmed, or at risk of being harmed, by the perpetrator. They argued implicit ‘mother blaming’ had been prominent in child protection discourse for decades, principally because DV had been individualized rather than its gendered dynamics and patterning being understood and acted upon. This position is also likely to have been exacerbated by social work’s often uncritical reliance upon traditional developmental psychology which concentrates the professional gaze on, above all, the mother’s shortcomings (Andenaes 2005). Humphreys and Absler identified three cross-national themes from 1900 to 2010 in relation to child protection: (i) the absence of male perpetrators from child protection assessments or interventions; (ii) the exclusion of DV from standard assessments or formal meetings and, if recorded in case notes, its being reinterpreted as ‘marital arguments’; and (iii) the representation of DV as a private problem with the onus on the woman to resolve the issues. Interventions, for more than a century and across different countries, have focused upon the responsibility of the mother to protect children but have paid little attention to her support needs or the man’s responsibilities. Consequently, those working outside child protection, such as refuge workers, still report women being too frightened to seek help from social services for fear their children will be removed (Humphreys and Absler 2011; Keeling and van Wormer 2012). This concern is now so entrenched within the minds of poor families that many are deterred from even approaching health services for other kinds of help (Canvin et al. 2007).

Other recent UK studies also confirm Humphreys and Absler’s findings that mothers who are themselves the victims of DV are judged negatively and expected to resolve the situation singlehandedly in child protection cases, while men are overlooked and excused despite being the source of the problem (Hester 2011; Roskill 2011; Baynes and Holland 2012; Featherstone and Fraser 2012; Charles and Mackay 2013). Scourfield’s (2006) study of a child protection team found that, although social workers acknowledged many mothers’ economic oppression, their empathy diminished if the mothers failed to protect the children from violent partners. The social construction of gender which positions women as ‘naturally’ tied to childcare through social norms and policy (Daniel et al. 2005), together with insufficient support networks and services, helps explain why practitioners do not see gendered DV as the central social problem. This lack of recognition has far-reaching consequences for mothers’ ability to protect themselves or their children.

In cases of DV there is both a child and an adult victim, but child protection work focuses on the child, rarely invoking broader-based interventions (Featherstone, White and Morris 2014). The benefits of a broader focus are demonstrated by a recent study with 2,500 women, which found that intensive case management, which also focused on maternal support, greatly improved children’s safety, and also reduced parent–child contact conflicts (Horwath et al. 2009). Many studies recommend inter-professional training which co-ordinates inter-agency goals and leads to cooperative working, but, without adequate recourse to effective family-based treatment alongside an understanding of gendered violence, this is unlikely to be effective (Humphreys and Absler 2011). This does not, however, mean social workers are powerless, and, although they work with individuals, collective responses and pressure groups can change and have changed policy. However, to be sufficiently willing and adequately informed to consider these strategies social workers need to understand the social construction of gender, gender inequalities and gendered violence, and to be able to conceive of DV in these terms. Abused women are rarely seen as vulnerable unless they have physical or learning disabilities, or are elderly or mentally ill (Humphreys and Absler 2011), but, as the next section on adult safeguarding shows, even those deemed vulnerable do not necessarily receive sufficient protection from social workers.

Adult protection/safeguarding issues

A number of studies on abuse of adults have shown that knowledge of policy among practitioners, including social work professionals, is variable, and that they work with a number of different definitions of adult abuse. Their working definitions are often narrower than those enshrined in policy, some excluding abuse by other service users or inadvertent neglect, or vary according to resource availability (Brown and Stein 1998; Johnson 2012). A study in Scotland looked at how professionals constructed adult protection issues and implemented inter-agency practice (Johnson 2011). It examined the cases of twenty-three ‘at-risk’ adults in four local authorities, covering adults living alone, in families or staffed settings, and including individuals with learning and physical disabilities, physical and mental health issues, and older adults. Johnson identified four main issues: (i) professionals interpreted protection issues and policy in different ways; (ii) organizations and over-loaded carers were rarely held culpable for failing to protect; (iii) service users were only seen as victims if they were submissive, passive and deserving; and (iv) safeguarding issues were not linked with more macro social inequalities (such as ageism, inadequate care budgets and the low social status and political priority of vulnerable adults). As a result, the abuse of vulnerable adults was not recognized as a social problem.

In Johnson’s research, in relation to (i) differential interpretation, a young woman, with probable but undiagnosed learning disabilities, often had sex with strangers when inebriated, and later married a man suspected of assaulting her. She was considered vulnerable by social workers but not by her former therapist or the police. They deemed her to have capacity because she rejected any intervention. One social worker said he would view just one instance of sexual exploitation as a protection issue, but physical assault only if severe and repeated, although others disagreed. Some incidents were labelled as ‘poor practice’ rather than abuse in some institutions/organizations, although others responded differently to similar instances. Regarding (ii) organizations and carers not being judged culpable, in just under one-third of the cases the suspected perpetrator was an institution. Examples included one housing department placing a vulnerable young woman with mental health difficulties in a predominantly male facility that accommodated known sexual predators; police failure to investigate an assault; a medical consultant discharging a man with dementia into a very unsafe environment; and the under-resourcing/ineffectiveness of certain services, which led to direct vulnerability and neglect. In one case, a mother developed dementia and was no longer able to care adequately for her learning-disabled daughter. The case was designated a protection issue and an agency was contracted to provide daily support but was extremely negligent. Despite this, neither the agency, nor the contracting body – Social Services – was held responsible. Policy was also not written in a way that allowed institutional failings to be dealt with, and the institution dealing with complaints was often both the social worker’s employer and the organization responsible for providing the person’s care, either directly or indirectly.

As regards (iii) passivity, deservingness and vulnerability as the basis for deciding whether a situation was one of adult protection, one physically disabled man vocally and repeatedly alleged his father regularly beat him but social workers perceived it as a ‘tit for tat’ relationship, in which he had capacity, and therefore it did not raise adult protection issues. In contrast, a man with learning disabilities who drank alcohol voluntarily with his cousin, who routinely stole from and humiliated him, was seen to be a vulnerable victim due to diminished mental capacity, despite his not manifesting any distress. Johnson’s findings concur with Loseke’s assertion that the most successful social problem claims occur when victims are perceived as blameless and passive, with abusers being ignored unless they can be projected as monstrous and qualitatively different from most ordinary people. This suggests a parallel between how lay people perceive social problems and how social workers respond to issues which could be deemed to be social problems. What seemed to influence these professionals’ construction of an adult protection issue was their perception of the service user’s vulnerability and best interests, and whether they felt intervention with the resources they had would make a difference. For example, they might believe that a vulnerable adult who was being neglected by his main carer because of limited resources did not constitute a protection issue because his treatment at home might still be better than if he was moved into residential care. It is also interesting that when scandals about the care of elderly people erupt they tend mostly to focus on abuse within institutions, which may also influence practitioner and lay perceptions of what constitutes abuse.

Ash (2013), from interview research with thirty-three social workers and managers, found, in the context of limited resources and high caseloads, few workers were able to envisage how difficult it might be for elderly service users to disclose abuse. Many of Ash’s findings mirror Johnson’s, including practitioners turning a blind eye to abuse in care homes if the homes complied with regulatory procedures, and reframing abuse as poor practice. They also failed to ask persistent questions about the absence of support for elderly people because they were unable to envision alternative possibilities, or contextualize elderly people’s position within a wider social and cultural landscape. They implicitly accepted that, due to inadequate societal resources, which they did not believe could be increased, older people were likely to be abused or neglected and there was nothing they could do.

These two examples – child protection in the context of DV and adult safeguarding – illustrate how social workers tend to adopt a narrow individualized approach dictated by organizational policies and resource availability, with little consideration of wider structural issues such as gender inequalities, ageism and poverty. Domestic violence and the abuse of vulnerable adults constitute social problems because of their frequency and effects, and both receive intermittent media coverage, but there has been a reluctance to accept the gendered nature of DV or that the abuse of vulnerable adults may require collective responses and system changes. The fact that society accords victims of DV and vulnerable adults few resources implicitly condones widespread violence. Social workers are professionals who supposedly uphold human rights and social justice; however, these examples show that by failing to challenge the lack of resources they collude with the status quo. Preston-Shoot (2011) exposes the fracture between professional ethics and workers’ obeisance to bureaucracy and statute as an ‘administrative evil doing’. Arendt (1963), referring to Nazi Germany, argued that ‘banal evil’ derives not from monstrous people or demonic actions but from unthinking conformity and a dulled conscience. Bauman (1989) coined the term ‘distanciation’ to describe a situation in which people are separated from the consequences of their actions or perceive their actions as purely technical. This occurred in Nazi Germany when social workers carried out assessments which were later used to justify genocide or enforced sterilizations of certain groups (Waaldijk 2011) but could be argued to occur in contemporary care management where social workers’ personal involvement with service users is limited to assessment and most services are then contracted out. The fact that it is frequently undercover journalists, and not trained health and welfare professionals, who expose the abuse of vulnerable adults is of great concern. Social workers could draw on the professional codes of practice, human rights legislation (e.g. Article 3 of the 1998 Human Rights Act – the right not to be subject to inhumane and degrading treatment) and whistleblowing legislation to challenge institutional practices, but seem rarely to do so (Ash 2013). They could work collectively and with other professionals, service users, MPs, activists and pressure groups to have issues such as these recognized as legitimate social problems and to campaign for better understanding and resources, but such mobilization requires an understanding of why it is important to do this. Loseke’s work on how certain social problem claims become accepted as legitimate is a useful framework to work within, although clearly it requires some complexity to be sacrificed.

3.8 Conclusion

Social workers work with a variety of social problems, including child abuse, mental illness and the care of older or disabled adults. This chapter has shown how the identification of social problems is a social and political process which is shaped by how the issue in question is understood. For this reason, social workers need to have some understanding of different sociological perspectives on the nature of society and on the processes by which social problems are recognized. We argued that social constructionism is a useful perspective through which to analyse social problems, and it enables social workers to reconstruct and re-present social problems in ways more beneficial to their clients. Child abuse and wealth offer two contrasting examples of the way in which different social interests are deployed, leading in one case to the identification of a new social problem which then became broadened and in the other to a problem being ignored or implicitly denied. The discussions of DV and adult protection illustrate how, even where a social problem is recognized, too narrow a focus on the causes at an individual level may mean that wider structural causes, such as the gendered nature of DV or the under-resourcing of adult services, which require a more political response, are overlooked.

Social workers play a key role in implementing policies directed at a wide range of social problems and groups seen as a problem in society. Many enter social work with laudable aims in relation to supporting vulnerable people, or occasionally with the wider goal of combating social injustice. However, much research shows they frequently work in parochial, depoliticized and individualized ways. This often results in them inadvertently reproducing dominant, inequitable discourses and upholding oppressive stereotypes associated with a social pathology or deviance perspective on social problems. We hope that this chapter will enable social workers to critically analyse how social problems are constructed and the impact of this upon the social policies which inform and direct their work, and provide them with the necessary knowledge and professional confidence to understand service users’ problems within a broader context. Through this, they may be able to recognize and challenge oppressive policies and practices both institutionally and politically, as well as working effectively with service users at an individual level.

Discussion questions

- Choose an issue conceived of as a social problem and not examined in depth in this chapter (e.g. obesity, unemployment, substance misuse or immigration). Discuss how it has been socially constructed and the consequences for the kinds of policies proposed to address it.

- How could the issue you chose have been constructed and represented differently, and what effect might this have on how social workers perceive and respond to such issues?

- Take one of the social problems discussed in the final part of this chapter and devise a set of practice guidelines for social workers in the light of the issues identified.

- How might social workers engage productively with the micro context (small-scale interpersonal interactions with individuals and groups), the meso context (the mid-level of organizational practice and policies and communities and neighbourhoods) and the macro context (wider societal attitudes, norms, values and policy and legislation) in respect of one or more social problem groups?

Further reading

- Hacking, I. (1991) ‘The Making and Molding of Child Abuse’, Critical Inquiry, 17 (2), 253–88.

- Johnson, F. (2012) ‘Problems with the Term and Concept of “Abuse”: Critical Reflections on the Scottish Adult Support and Protection Study’, British Journal of Social Work, 42: 833–50.

- Lister, R. (2010) Understanding Theories and Concepts in Social Policy, Bristol: Policy Press, ch. 3.

- Loseke, D. R. (2010) Thinking about Social Problems: An Introduction to Constructionist Perspectives, 2nd edn, Aldine: New Jersey.

- Weinberg, L. (2015) Contemporary Social Constructionism: Key Themes, Philadelphia: Temple University Press.