Chapter 10

Using the Nine Steps to Bring Your Initiative to the Real World

Understanding each of the nine steps of the Stacking the Deck process provides a strong basis for leading breakthrough change. Now we need to examine how these steps fit together and build on each other. We'll then delve into additional topics to further prepare you to lead breakthrough change.

Stacking the Deck is written for an audience of emerging and more experienced executives, whatever your specific position. It is not intended as Management or Leadership 101; it does, however, emphasize critical aspects of those management and leadership skills that are especially necessary for success with initiatives of this nature.

Navigating and Sequencing the Nine Steps

Think how quick and easy change initiatives would be if you could simply move from one step to the next, each step getting you exactly one ninth of the way to the desired outcome. But the Stacking the Deck steps are neither literal nor linear. Instead you'll have to undertake some parts simultaneously; and occasionally you'll need to double back, to redo a previous step on the basis of the work in a subsequent step. These are not the directly linked steps of an escalator, nor are they as convoluted as the never-ending staircases depicted by the Dutch graphic artist M. C. Escher. They are, however, somewhat fluid in ways that can work to your advantage—now that you're alert to the process.

Step One, Establishing the Need to Change and a Sense of Urgency, is indeed the starting point for a breakthrough change initiative. But in most cases, the process of communicating the change extends to a very limited audience in the beginning. Since we don't yet have a team committed to the solution and we don't have a detailed or precise vision of what the solution is, we cannot go running around communicating that we have a problem. So with the proviso that Steps One, Two (Assembling and Unifying Your Leadership Team), and Three (Developing and Communicating a Clear and Compelling Vision of the Future) involve a small circle of executives, these steps can be considered as fairly linear.

In Step Four, Planning Ahead for Known and Unknown Barriers, we begin to expand the circle of active participants and bring more voices, players, and perspectives into the process. In doing so, we revisit Step One and communicate the need for change along with the vision of the future that we developed in Step Three. Our work on the barriers described in Step Four, particularly the section on planning for the unexpected, leads us into the planning process of Step Five.

Steps Five (Creating a Workable Plan), Six (Partitioning the Project and Building Momentum with Early Wins), and Seven (Defining Metrics, Developing Analytics, and Communicating Results) build on each other and connect to support transformative change. Aspects of these steps will need to be repeated and revised over time and the process remains incomplete until all points have been laid out and thoroughly enumerated.

Step Eight, Assessing, Recruiting, and Empowering the Broader Team, which will be hands-on throughout the initiative, will actually begin during Step Four, when the leadership team contemplates the potential barriers to overcome and the required skills. Looking ahead to determine the skills and experiences you will need is critical—since you may have to go outside the company to recruit if they don't exist within the company's existing pool of talent. Since this could consume considerable amounts of time, money, and effort, getting an early handle on your needs and working in parallel with the other steps is very important.

Step Nine, Testing with Pilots to Increase Success, is typically the last step to implement. But there can be exceptions. There may be instances in which a small pilot having a hand-picked team, a favorable market, and a minimally viable prototype can be tested very early in the life of the project.

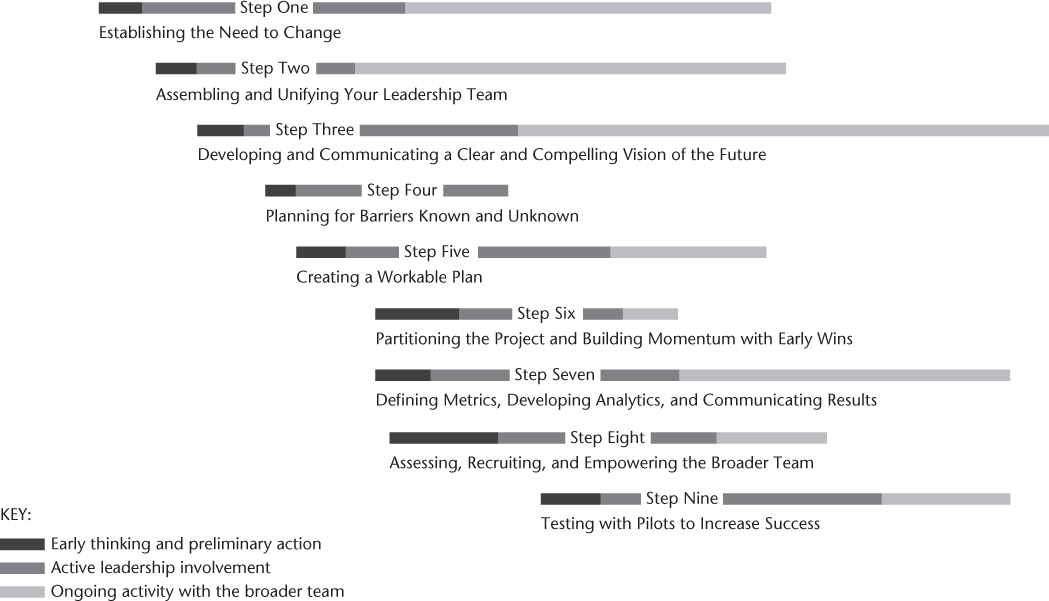

The nine steps usually begin in the order presented in this book; the sequencing and overlap of steps will vary depending on circumstances. Figure 10.1 illustrates how the steps might be sequenced relative to each other. Precise timing will depend on circumstances and resources. Remember that there will naturally be some amount of overlap among steps and parallel work efforts along the way. After all, if breakthrough change were a straightforward, lockstep process, experienced leaders wouldn't constantly emphasize how difficult it is.

Figure 10.1 Sequencing the Nine Steps

Leading with Conviction

When Asurion's Steve Ellis and I were discussing the challenges of leadership and the difficulties in leading breakthrough change, he shared some thoughts that are especially relevant as you begin navigating the Stacking the Deck steps: “If you don't have true, deep, enduring conviction about the importance of the change you're pursuing, you will be buffeted, worn down, ground down, and diverted at those critical points where leadership is the only force that keeps the change moving. The biggest mistakes that I see come during those points. At root, the mistakes arise from the dissipation of conviction—leadership and management conviction.”

Steve explains how the momentum at the start of an initiative can occasionally stall, leaving leaders in a tough spot: “There's always a lot of fanfare at the beginning of any big change. At this point, leaders can convince themselves that the change is important and needs to be treated with the appropriate urgency and energy. There's enormous energy put into the front end—in defining the point of arrival, establishing the management and communication infrastructure, creating the case for change, and assigning clear leadership and accountability. But all too often, people fail to fully appreciate what defines the finish line or the major milestones.”

His thoughts reminded me of a hard lesson many CEOs learn while working with their boards: It is far easier and more productive to discuss weaknesses and strengths of the project at the outset rather than once it's under way. If you don't carefully consider the terms and resource needs until you are farther down the road, or if you overcommit, then your request for more time or money may be seen as a sign that you are slipping or missing your commitments. It is much better to negotiate these needs up front. Similar lessons also apply for non-CEO leaders of breakthrough change.

Steve and I both understood that the actual milestones for the change are not simply financial objectives. And they might not show up in classic metrics such as average hold time, volume of subscribers, efficiency metrics, revenue in a new market, working capital requirements, or any of the typical measurements that you might use to define the success of a change program.

“Instead,” Steve added, “the breakthrough change actually requires people on the front lines of the business, the customer service reps, the field people, the person on the manufacturing floor, the rep taking the sales order, the person developing the new technology platform, to be thinking fundamentally differently about the nature of their jobs. They need to be open to learning to do new things, using new tools and capabilities, breaking old rules, upgrading their skills, investing in their own capabilities and the organization's capabilities to do something fundamentally different.”

We agreed that when a change process is widely distributed along the front lines, “leaders have to touch potentially thousands if not tens of thousands of people” in order to make that change happen. “The distance between the PowerPoint slides and the proclamations and the strategy documents and that frontline person fundamentally embracing and executing this idea, with reliability and consistency, is simply enormous. The change process is a long road and there are so many potholes, diversions, and off-ramps along the way that leaders often underestimate what it takes.” Steve knows what he's talking about, having learned these lessons firsthand: “Most leaders—myself included—almost always underestimate what it takes to get to that point. We fail to accurately define what bold change really is and what it really demands.” Much as we might hope for an easier path, “there's simply no silver bullet for getting human beings to change. It's a ton of really, really hard, roll-up-your-sleeves work to accelerate the bold change process and to make it stick over time. Even with the best possible strategies, you'll need the time, energy, and emotional fortitude to carry, pull, or drag the organization through those ebbs in conviction when people are seeing all the pain of the change and none of the benefit. That dip in morale is always a perilous point in any change process.”

What Steve was saying resonated with me. I knew how critical it was to get past the dips Steve was describing when he said, “The longer this kind of dip goes on, the more the change will dissipate and diffuse. You'll never even get to the point that people in the front lines have fundamentally changed the way they do things—or see that outcome you were looking for when you proposed your change.” As he said, “If you're not ready to carry on through those moments and you haven't personally built up your reserves and anticipated the need for a sustained investment of resources, financials, human capital, and emotional endurance, then you will not survive those trying moments.”

Sobering words, but important thoughts for leaders at all levels to bear in mind. Whether in the boardroom or managing operations on the ground, leaders need the conviction, the determination, and the energy to see the change through.

Negotiating Terms

The CEO needs first to negotiate with the board regarding expectations for a breakthrough change initiative. But what of the operator who will be tasked with actually leading the change on the ground? Imagine a major initiative that might just transform the future of your organization. Your superiors have already navigated Steps One and Three and they are looking to fill out the leadership team, complete Step Two, and get the project rolling. The project involves a certain level of risk, and to mitigate that vulnerability they need a strong, capable leader to organize the initiative. Then your boss walks in to inform you that you have been selected to lead this critical, but risky initiative. What do you do?

You may well be eager to launch your project and get a sense of exactly what it requires, while shoring up your own bargaining position with some incremental successes. But starting too quickly may be a mistake. You have the most leverage before the project begins—perhaps even before you formally sign on. So before you irrevocably accept this assignment and get rolling, you need to thoughtfully assess the resources you have been assigned and establish clear parameters of success and failure for your efforts. The board may have seen the big picture, but you need to carefully consider Steps Two, Three, Four, and Five as you begin the process of negotiation. Resources, deadlines, deliverables, and decision rights are the major terms you need to codify and agree upon early in the process.

It's tempting to think that success and failure are clear, distinct, and self-evident. A project that invests $5 million and makes $12 million is a success, right? But what if it was supposed to make $20 million? The difference between success and failure can be completely in the eye of the beholder. How we set and negotiate expectations with our superiors or with shareholders and analysts can determine whether a breakthrough change is hailed as a huge success or seen as long overdue or, much worse, too little too late.

You want to lead this project, but as you hear about the thinking that's already begun to develop, your sense is that the expected outcomes are entirely too aggressive. They want too much, too fast, and with too few of the resources you believe are necessary. This is nothing new in business. Leadership is all about setting high expectations and then inspiring the team to strive toward success. You can't simply communicate deadlines and deliverables upward; instead, you need to negotiate from a place of strength and knowledge to secure the best possible framework for your project.

Be aware that you may be setting yourself up for difficulty and disappointment if you agree to take on the project as is. When you (inevitably) disappoint sky-high expectations, it is seen as your fault rather than the result of overly ambitious initial terms. There is typically little room for renegotiating terms after the fact or explaining away the reasons for a failure that “wasn't your fault.”

The time to set the terms then is at the outset of the initiative. You must also be very clear with your team members about where their responsibilities and duties begin and end. Just as you have to carve out your own authority, you must do so for the people under you. Don't postpone these conversations.

You may not be able to get everything you want or need in the beginning. There are some firm limits in any negotiations. But a thorough conversation early on can help you discover where there is give. The deadline may be dictated by the realities of competition or already negotiated and set at a higher level of the organization. But perhaps the deliverable can be scaled back to a pilot implementation or a limited-scale rollout that will require less time and money than a full implementation.

Decision rights, unlike deadlines and resources, are more flexible and perhaps the most dependent on early negotiation. You need to know what decisions you are allowed to make, how fast you can move, and when exactly you need to get higher-level approvals. If you establish yourself as someone willing to accept an extraordinary amount of managerial oversight without argument, or wait until your project is already under way to begin asserting yourself, you will find it very difficult to get away from that initial perception.

You will be held responsible for the initiative's outcome, as well you should be. You must therefore negotiate carefully up front, nailing down as many issues as possible and with as much precision as possible. Understand that when you take on a breakthrough effort, you take on responsibility for any development and may be held accountable for decisions you neither made nor recommended. Sometimes that's exactly what must happen. Keep the big picture in mind and control what you can.

Getting Started

Whether you are the CEO or the operator driving the breakthrough change, bear in mind that—as a Schwab colleague pointed out to me years ago—it's important to “go slow to go fast.” Greater diligence in the early planning stages of a project may allow multiple teams to work simultaneously on multiple threads and achieve a significant effort for less money and in a shorter amount of time. For those of us who are eager to get going, who can't wait for the future, this can be a difficult concept to embrace.

This has never been easy for me since I am typically mired in the idea of “go fast and then go faster”—at least until some particularly strong form of resistance pops up to remind me. Try as I might to change it, my instinct is never to “go slow to go fast.” This shortcoming is but one example of how diversity on the leadership team can pay off. I have surrounded myself with people who fully understand the importance of going slowly and carefully at the outset and who know to push back when my own instincts for speed are getting in the way. This is one of many skills I am still working on. Whatever yours are, be sure you've included people whose strengths counterbalance your weaknesses.

Once the leadership team is on board at the beginning of big, breakthrough change initiatives, many (if not most) of these leaders will want to get rolling and begin to see “real” progress. And by “real” progress they often mean seeing change actually happening, not just a bunch of people conducting endless meetings mapping out a transformational breakthrough effort. Still, these slow, methodical steps are exactly what is needed and anything else will result in disappointment and wasted time, effort, and money.

In addition to the reminders to go slow to go fast, the principles described in Geoffrey Moore's classic, Crossing the Chasm, can provide immensely helpful information. Often, especially in the high-tech world, you can find an audience who will adopt almost any new idea. These “early adopters,” as Moore refers to them, will overcome bugs, inconveniences, poor service, inadequate user manuals, and other difficulties in order to have the latest technology. They buy in to new product concepts early, not for the novelty or to be first, but because they can “imagine, understand, and appreciate the benefits.” In retrospect, this idea made clear why a number of programs we developed early on at Schwab took off with a certain group of investors and then stopped growing. For example, we developed personal accounting software called “Financial Independence,” which had a solid if not spectacular launch. We had satisfied Moore's “early adopters”; however, we did not have the organizational structure and operating discipline to improve the programs fast enough to reach a larger market. With a faster cycle time, we might have been able to learn what wasn't working for consumers and then change the programs to appeal also to Moore's “early majority,” the roughly one third of potential customers who simply won't tolerate the glitches or problems that early adopters accept.

Having not succeeded with this middle group, we didn't stand a chance of attracting the “late majority” (the final third) who watch and wait, not buying until the product or program “has become an established standard.” Our success with the early adopters simply could not translate to a larger group because we had not crossed the chasm Moore describes. In contrast, Scott Cook and Tom Proulx had enormous success in creating and constantly improving Intuit's Quicken, personal finance software that was easy to use, intuitive, and ever evolving.

In many ways, the ideas Moore presents parallel the ideas behind proof of concept versus scalability pilots. Just because something works once or works with a select group does not mean it is ready for widespread rollout and the harsh test of mainstream reality. In fact, as Moore's book title telegraphs, there are chasms between groups; it's crossing those chasms that presents the challenges. Whether our initial success comes from a pilot or a rollout to the early adopters, ultimate success depends on building momentum and recognizing that early, initial success is just that. It's the beginning of bringing the initiative out to the world, not the end.

Dealing with the Risk of Failure

When we talk about breakthrough change and pioneers, we must inevitably talk about the risk of failure—perhaps even on a large scale. Your people are going to be nervous about the prospect of risking their careers and reputations on untested ideas. What then should a leader say when asked, “What are the personal consequences if we are not successful here? Is it okay to fail?”

These are difficult questions. Leaders certainly can't say, “Sure, it's perfectly okay to fail!” because it's usually not. An answer that is often heard is, “Well, it depends.” Obviously, this is more of a non-answer and doesn't offer any useful or reassuring guidance.

Noble Failures Balance the Risk

In an attempt to better answer these often unstated questions about failure, I have elaborated on a concept called Noble Failure. I knew that, as the Irish poet, critic, and educator Edward Dowden (1843–1913) put it, “Sometimes a noble failure serves the world as faithfully as a distinguished success.” But I suspected that these words from his time would not allay people's fears today. For example, who decides if my failure is “noble”?

I have contemplated the concept of Noble Failure and given it specific conditions. The concept reflects the recognition that big breakthrough change initiatives inevitably run the risk of failing. And it is an acknowledgment that often failure is not a result of incompetence or lack of effort; instead, it is due to any number of factors over which you have limited control. Projects can still fail even if you carefully go through every step in the Stacking the Deck process: stacking the deck cannot guarantee success. Perhaps the idea behind your initiative was fundamentally flawed. Or perhaps as you were in the middle of the project, another company came out with a superior product. These are the kinds of risks that you can never fully avoid or neutralize. We need a new category of failure to describe such situations.

Noble Failure, in my view, has seven important conditions:

- The project was well planned. You did your homework and you crunched the numbers. You used intuition where appropriate.

- You failed smart and small. Whenever possible, you confined your failure to the lab or a pilot program like those covered in Chapter 9. You used models and prototypes and conducted lower-cost tests whenever feasible.

- You had a contingency plan. You knew the places where the plan was most likely to get off track and were prepared to slow it down and steer carefully through the curves if necessary.

- You didn't bet the company. The failure didn't cost so much money that the company is now in financial trouble. You considered opportunities to syndicate the risk with other organizations if appropriate.

- You limited the negative fallout. This failure was not hugely public; it didn't cause a compliance, legal, or public relations fiasco. You did not imperil the company's reputation.

- You followed a policy of “no surprises” with your superiors. If the project was struggling, you let management know so they could potentially help you or prepare contingency plans you had not thought of.

- You learned from your experience. After a Noble Failure, you conducted a postmortem and tried to extract learning opportunities from this experience both for yourself and for the organization.

If each of these conditions has been considered and observed in depth, before, during, and after the effort, then the outcome may be thought of as a Noble Failure. In that case, what we don't do is punish the person or the team who originally proposed, advocated, or led the change. This is not about rewarding failure but rather about not punishing courage and innovation. Ideally, with the company culture behind you, a Noble Failure is a kind of neutral for your career: you don't advance, but you do survive professionally. It may even be a benefit, because you now have the experience of trying and failing and can apply that experience and the lessons you've learned to future projects. The Noble Failure concept is intended to encourage people to voice their opinions and ideas more freely because they know that even a failing effort will be tolerated, sometimes even celebrated, and never punished.

Early in my Schwab days, we developed online trading software called the “Equalizer” (sadly, I am responsible for that corny name). Because no other discount trading firm had such a product, it garnered a small, very loyal following. It just wasn't user-friendly enough to attract a big and profitable client base. We learned from this experiment and years later replaced it with “StreetSmart” software based on an early version of Windows (and better named by someone else). This was much more successful, but it certainly wasn't a breakthrough. However, no one's career suffered for the lack of breakthrough success with either of these software products. Instead these efforts prepared us for the Internet and the explosion of online trading that followed. Because of these efforts, we all learned what we needed to set ourselves up for success in online trading. This was Noble Failure at its best and ultimately led to StreetSmart Edge® and StreetSmart Pro®, vastly reengineered products which are part of Schwab's services today.

Anticipate and Manage the Risks

It is true that breakthrough change takes even longer if things go wrong. The planning processes included in Steps Four, Five, and Six are the best, most efficient time to take a preventative look at risk factors and develop strategies to mitigate them. The process of assessing and planning for risks is not something you do once and you are done. It is a constant activity, since conditions change and new risks can come at any time from a host of places. For instance, scope creep (below) never goes away. It remains a risk right to the conclusion of the initiative.

Risk factors can develop from both from inside and outside the company. Anticipating and managing through internal risk factors is much more straightforward than dealing with the external kind, such as regulatory changes or strategic moves by competitors, which can drop roadblocks in your path. These obstacles are generally hard to anticipate, so you must be forever vigilant looking for early indications that adversity is lurking on the horizon. The sheer number of outside complications that might influence your organization means that it's impossible to develop enough Plan Bs to counter every vulnerability.

As much as you try to identify and plan to deal with risk, there will always be uncertainty when you are breaking new ground—and you must learn to live with that uncertainty. Indeed, your ability to lead and inspire in the face of uncertainty is an important part of the breakthrough change process. If you've worked through the Stacking the Deck steps, you should already have identified some areas of risk. Over the course of my career, I have managed to sort the risk factors of breakthrough change into seven planning categories. Developing an awareness and a plan for these problems won't save you if something in the market goes awry or a competitor scoops you, but it will allow you to protect your project structure from those hindrances that you can manage or even avoid.

Scope Creep

From the outside, adding new elements to a breakthrough change initiative might seem productive and logical. Since we are already changing so much, why not add a few more things to the list? You will have to stand firm on the boundaries of the change and resist suggestions that might overwhelm the focus of the project. This will not be easy. Some of the impetus for scope creep may come from your own team, or even from the face in the mirror. Resist! Put these new ideas into Phase Two or Release 2.0 of your initiative.

The Technological Stretch

You have to contextualize this risk in more than one way. Essentially, you want to take this query through three descending levels:

- Has this technological change ever been done?

- Has it ever been done in our industry?

- Has it ever been done in our organization?

As you can imagine, the risk decreases steadily as you get closer and closer to your organization. The more commonly utilized a technology is, the easier it will be to find the talent and experience you will need to be successful. If your idea is something that has been done in the industry, then you might already have reliable consultants to bring onto your team. Even better, if something similar has been done in your organization before, you may be able to readily access the expertise you need within your own organization via a reassignment or loan. But if the change you are proposing involves something that has never or rarely been done before, anywhere, you are taking on a much larger risk. Sometimes you have to evaluate whether the “bleeding edge” is worth the potential risk. This is a very tough call. After all, it's called the bleeding edge for good reason.

Consider the Apple Newton. Released in 1993, it relied on handwriting recognition, a risk that turned into a bad gamble because the feature fell far short of expectations, hurting Apple. The early digital assistant insight was essentially on point, but the way it became expressed and executed was a failure, particularly once Blackberry broadly commercialized the breakthrough innovation of tiny handheld keyboards and thumb typing. In time, the Newton concept of the touchscreen became a major driver in mobile technology innovations, including Apple's iPhone and iPad.

The Business Stretch

This is the flip side of familiarity with the technology focus. As such, the questions are quite similar:

- Has a project like this ever been done?

- Has it ever been done in our industry?

- Has it ever been done in our organization?

You need to know if the company has ever done anything similar from a business model or conceptual design perspective. Is what you are proposing totally foreign to the people within your organization? What about the managerial structure? What about cultural implications?

In suggesting that we change how the Schwab branch offices interacted with customers, I failed to realize how novel the change would be to Schwab. The change was nothing new within the traditional brokerage industry, but it was totally new to Schwab. It seemed like a small issue, but it actually required employees to essentially do the opposite of what they had always done: be proactive rather than reactive. A change that is foreign to the company can work, but it's going to take longer and cost far more, and it will need to generate sufficient benefits to be worth the effort.

Maintaining the Team Through the Project

Once you have developed a strong team for your project, you need a strategy to maintain them as a group and as individual contributors. Breakthrough change initiatives are very challenging, especially for the members of the core team. The excitement and momentum that you have carefully built can evaporate as an initiative stretches into months and years. Difficulties, coupled with a protracted time frame, can put a lot of stress on team members; over time, all this can reduce their morale. Success, on the other hand, can be something of a double-edged sword. The higher profile your project, and the more outstanding the results, the greater the likelihood that team members will be recruited for other opportunities both inside and outside the company.

Be prepared for long-duration projects to test your resolve and the resolve of everyone around you. Be sure to put in time and effort to keep team morale high. The time required to do so is substantial—and absolutely necessary. Breakthrough change is a lengthy process. You can reduce the impression of the project taking too long and maintain momentum by breaking the effort down into smaller components early on, as described in Chapter 6.

Keeping Management on Board

Your superiors will likely not be comfortable with a change that plays out without interim results over an extended time, and competitors are certainly not sitting around and waiting. The best way to prevent a loss of interest and resolve is to make sure that you keep management in the loop at all times. Just as you need to build and maintain excitement about the project among your team members, you need to do so at every other level of the organization. This includes your shareholders, investors, suppliers, customers, and bosses, as well as your subordinates. You have to get them on board, build excitement about the project and its progress, and keep them looking forward. As you do this, realize that the stakes go up. The higher the project's visibility, the more important success becomes to the organization—and to you.

Investment Size

You need to be honest about the size of this change. Risk increases proportionately with size. Is this a $2 million change or a $20 million change? Of course, financial size is a relative matter. To some organizations a $5 million project is a rounding error, and to others it is a bet-the-company investment. You must determine what kind of impact a failure would have on the organization as a whole. Is this a bet-the-company change? Or is it, potentially, a storm the company could weather? This is not to say that you shouldn't initiate bet-the-company changes—I've done it myself—but you may have to reconcile yourself to significant personal risk, as well as risk to the organization as a whole. It is my very personal belief that you don't financially bet the company unless competitive circumstances demand such a move and everyone in leadership is totally behind you.

Quality of the Planning Effort

If you have followed all the steps up to this point, you will have already mitigated this potential problem. Remember that too much optimism can have a detrimental effect on your ability to plan. But you can also sabotage your plans if you are unable to recognize potential problems and create contingency plans. As discussed in Chapter 7, clear and consistent metrics that let you know the limitations and see the warning signs are critical. If you skimp on the legwork at the beginning, you may be blindsided by one or more of these risk factors later on.

Even if you carefully and diligently follow the nine-step process, negotiate terms, and consider the various issues and risks, you cannot guarantee success. Bringing initiatives to the real world is fraught with challenges. Given the history of breakthrough change initiatives, you already know the deck is almost always stacked against you. To give yourself the best chance of succeeding you must combine a tested, thoughtful process with an extraordinary dose of leadership. Bookstore shelves are packed with wonderful books on leadership. I encourage you to explore them all, to read the classic ones, and to stay current on the new ones.

Bold, breakthrough change requires leaders at all levels who can demonstrate courage and inspiration. This is seen in how they communicate with their teams. Unfortunately, solid communication skills are quite rare—and are therefore the topic of the next chapter.