Inertia, 2013, Jac Scott. Found broken, wooden chair, hand crafted flies, concealed metal fixings. 86 × 65 × 24cm. (Photo: Rob Fraser)

Inertia, 2013, Jac Scott. Found broken, wooden chair, hand crafted flies, concealed metal fixings. 86 × 65 × 24cm. (Photo: Rob Fraser)

STRATEGIES FOR BEING

Where did I learn to understand sculpture? In the woods by looking at the trees, along roads by observing the formation of clouds, in the studio by studying the model, everywhere except in the schools.

Auguste Rodin.

What is sculpture and how did it become like that? To even attempt to respond to this enquiry it is necessary to respect the notion that there are no definitive answers in art, and those who propose that there are, are misguided. Content in this understanding, I believe that the best way to start to comprehend sculpture is to examine the journey that was taken towards its creation.

The journey taken to achieve a work of art is guided and informed by multiple influences including any or all of the following: historic, political and social referencing, personal contextualising, innate impulses and compulsions, emotional and abstract inspiration and stimuli, peer work and review. The path can be direct or convoluted – the practice can stagnate or be animated, focused or divergent – artists are all different and their creative journeys reflect this. Studying some examples of strategies adopted to bring a practice or artwork into being, by a cohort of renowned sculptors, is both interesting and illuminating. Here the sculptors themselves talk directly about influencing elements that continue to shape their art practice.

PETER FREEMAN

I moved to Cornwall because of its reputation for natural light, I thought it would make a good backdrop to explore artificial light. The air is relatively clean and the sea is underlined by white sand so the colours can be very intense on clear days. Watching the sunlight reflected and transformed between the sky and the sea is a master class in the possibilities of light.

Cornwall does have a special quality of light but over the years travelling I’ve realised that everywhere has its own special quality of light – Birmingham at sunset used to be magnificent with all the industrial pollution.

I’ve come round to thinking that we carry our own light around with us. This is especially noticeable in Cornwall as it’s a holiday destination and people coming on holiday are lit up with the energy and enthusiasm of holidays that interacts and activates the natural light. If you fly over Europe at night there is a continuous web of artificial light mapping the landscape. The light reflects how we project ourselves into the universe as much as the needs for amenity.

The Cornish landscape and light I’ve come to appreciate is actually the more moody atmospheric light of winter with mists and storms and muted colours of moorland and winter seas. There’s a scale, power and monumentality that is very sculptural and emotional. I think it’s related to the romantic or sublime ideas in art. When I make light installations I’m trying to create a sense of the numinous form, a kind of point of contact between the external light and the light inside. I like to think that the external landscape and light can reflect a sense of being in contemporary moment that is beautiful and inspiring but also shifting and fragile.

Reflected Light, 2012, Atlantic Ocean, Penwith Peninsula, Cornwall UK. (Photo: Peter Freeman)

I was born in Moscow in the USSR not long before its dissolution. When I was five years old, I moved with my father to France for several years and have subsequently moved countries every five years of my life until now. I used to draw profusely as a child and keep a huge collection of the most unassuming, found things – thousands of chestnuts, oddly shaped stones and shells, dried leaves, discarded magazines, etc. Ironically, this notion of obsessive repetition and the reworking of discarded and found objects is very present in my work even now. The first thought of possibly following an artistic direction was when I was eight or nine years old and I won a prize at a junior Paris drawing competition. It was about imagining the future of Paris, and amusingly already then I came up with a fairly dystopian vision... Also in Paris, my mother used to often take me to the Musée Rodin, whose work I always found fascinating. It probably was my first real ‘introduction’ to sculpture.

My mother is a cinema and theatre actress in Russia and as a child I spent much time backstage during her rehearsals and performances. I always enjoyed seeing the reverse side of the illusion of theatre, watching the stage being built evoking such different places and states with often very limited means and minimal designs and all the personalities changing with make-up and costumes. Also, at that time I had the chance to meet many incredible writers, directors and musicians, which made me want to join that world from a very early age.

Principles of Surrender (detail), 2012, Nika Neelova. Installation Saatchi Gallery, London. Bell clappers cast in wax and ash, burnt timber, rope. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Stephen White, courtesy of Saatchi Gallery, London)

Principles of Surrender, 2012, Nika Neelova. Installation Saatchi Gallery, London. Bell clappers cast in wax and ash, burnt timber, rope. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Stephen White, courtesy of Saatchi Gallery, London)

I had started studying stage design in Moscow, but it is not until moving to the Royal Art Academy in The Netherlands, that certain interests became clearer. In that environment, I became preoccupied with sculpture and installation – with creation and destruction.

It could be said, ‘it all started with a cocktail stick and Rizla paper’, but my devotion to refined skill and craftsmanship were realised years before the first miniature model emerged. Concerned with the qualities of human scale, I worked on deconstructing life-sized pushchairs, prams, bicycles and wheelchairs, reassembling them to distort their original form and function. Facing the creative limits of this physical process, I followed the desire to re-create the vehicles in miniature scale; an experiment to realise the impact of changing the vehicles’ human scale. With what felt a purely intuitive process, I drafted a scale model, worked with the materials at hand (cocktail sticks, Rizla papers, paint, fabric, Fimo) and built a miniature pushchair, determined by the materials’ unrefined capabilities. I grew instantly attached to the process and charmed by the outcome, spending the coming weeks fixated on creating numerous models and photographing them within the context of interior and exterior environments. The miniature pushchair embodied a vulnerable, defenceless character, yet still captured a well-humoured presence. I began creating miniature stages and dioramas, calling on the human world as a setting for miniature calamities: falling, crashing, colliding and suffering human injuries simulated in the life-sized world. It was through this play that the strength of the miniature scale was actualised and my ambitions for developing miniature artworks flourished.

The process begins by producing a scaled plan of the object by taking real life dimensions or information from product manuals. Scaled orthographic and isometric drawings – varying from 1:12 to 1:16 – inform specific parts and components of the model that require further refining. Throughout the design process, my attention is constantly on material choices, often with the material dimensions determining the design of the model, such as the thickness of the mount board or length of a needle.

Untitled (black and grey wheelchair), 2008, Rachael Allen. Mixed media. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Rachael Allen)

A list of materials I commonly use to build my miniatures, although not exhaustive (some materials have been chance finds behind sofa cushions or at the bottom of my rucksack!) includes: cardboard, mount board, foam board, paper varieties, stickers, tape, textiles, wool, thread, ribbon, pins, wire, staples, paper clips, nails, screws, cocktail sticks, matchsticks, balsa wood, dowel, beads, sequins, jewellery, haberdashery, dolls’ house components, Fimo, clay, paint and ink. Materials are cut using a fine surgical blade, held by tweezers, positioned under a magnifying glass and glued using super glue gel. The process is meticulous, uncertain, time consuming and often painstaking; good eyesight, patience and steady hands are essential. Until recently, I have never drawn similarities between this method of working beyond that of a Airfix model maker. But in fact, it bears a resemblance to the precise actions of a microbiologist, surgeon, dentist and mortician, and even the work of a medical student dissecting a human cadaver; an encounter I am privileged to witness as an artist in residence in university anatomy labs. Medicine, life sciences, death and decay are unmistakable threads that run throughout my miniature artworks.

STELIOS MANGANIS

Occasionally I will stop working and thinking, generally avoiding any subject concerning the project. I will take a walk and just observe, without being critical. It is like placing the question in a forgotten drawer at the back of my mind, where not even I can gain any access. And then it just happens. It seems that my subconscious does not give up, and all the pieces somehow just fall into place. Throughout my working process, I try shifting the balance between intentional conscious thinking and the subconscious. This deliberate shifting between modes is, in itself, a strategy. Above everything, all these creative strategies form part of a master plan that I would like to call the mood. A creative outcome is hardly ever the result of a single strategy. One draws from the other; they co-exist. The mood is the environment under which these strategies can survive. At times, it is as if you are fooling your own mind and subconscious, by hiding your true aim for a creative outcome under a veil of playfulness.

Although I dislike doing so tremendously, I try to keep a handwritten log of all this research undertaken for each mechanism. This daily reflective journal facilitates personal contemplation in that I document the line of thinking followed during the project. It records moments of affective register, and my response to them as part of practical experimentation with the material. The journal holds all thoughts and processes; comments on the actions that had taken place, and make suggestions for further action. More precisely, it records the events and processes leading to the conception of artworks that have surfaced through the close examination of each encountered mechanism. An accompanying electronic diary with photographs, sounds and video recordings provides the documentation for retrospective reflection. I say I dislike keeping a daily log, because during a creative process, your mind rushes forwards – jumping from one thought to the next, from one concept to another, within a split second. Attempting to slow down this process so as to record your thoughts and actions is like driving a supercar during rush hour and being stuck in a traffic jam. You feel as if you are missing out on basic thrills of the creative journey. On the other hand, you might also discover new things outside your driver’s window, simply because you have slowed down and – who knows? – you might even take the occasional detour in which case you might never arrive where you had initially set out for.

KATE MCCGWIRE

I was brought up on the Norfolk Broads, surrounded by wildlife – by flocks of native and migrating birds, calling, nesting, swooping and circling overhead. That connection with water and birds has never left me, and today my studio is a barge moored on the River Thames, next to a semi-derelict warehouse filled with feral pigeons.

As a child I was always making things, constructing and deconstructing the world around me. For me it was a way to understand the world and make it my own. Occasionally we’d make family trips up to London, where a favourite place to visit was the British Museum. I remember in particular seeing the relics from Tutankhamen’s tomb and the Japan Exhibition, which was like nothing I’d ever seen before. These shows seemed to light something inside me, firing my fascination with art and objects. Later, when I moved to Paris aged 16 to work as an au pair, the city’s galleries were where I spent much of my spare time and learnt how to ‘look’.

In a way my work is a sort of process without end – a ceaseless cycle of collection and creation. While the making can take anything from a couple of weeks to a few months the collection of the materials can take years. I create the basic form on paper first – I’ll often sketch an idea with no immediate plan as to how to use it. Working in this way allows me free rein of shape and scale, and to experiment in a way that is impossible when using actual materials. The feathering stage is much more like painting; it’s at once fluid and expressive, and requires meticulous attention to detail. It’s also highly meditative. So much so that I often become completely immersed in the act of making; I often look back at a finished piece of work and think, ‘Did I make that?’ As if the work takes on a life of its own.

Occulus, 2013, Kate MccGwire. Mixed media with magpie feathers. 35 × 35 × 32cm. (Photo: Tessa Angus, courtesy of All Visual Arts)

Kate MccGwire working in her riverboat studio, Thames, London. (Photo: Tessa Angus, courtesy of All Visual Arts)

The pigeon feathers come from a network of pigeon-racing enthusiasts I’ve been building up over the last five years. By necessity I’ve had to become fully conversant with the pigeon-racing world and I can’t tell you how supportive they’ve been. I once took a stand at one of the annual pigeon shows in the far North-East of England; people were asked to bring along bags of feathers and in return got their names put into a hat to win a work. It all felt a bit incongruous but I was made to feel very welcome – the racing fraternity seems to love the fact that I’m making something beautiful out of their precious birds’ moultings. The birds shed their feathers twice a year, in April and October, so there are just two brief windows of time in which to gather my materials.

The business of collecting the feathers and creating a work feels satisfyingly intertwined, and creates a kind of virtuous circle all of its own. Relying on the goodwill of a whole network of individuals gives a human dimension to the process, which is mirrored in the many hands required to complete the work. The crow, jackdaw and magpie feathers come from local gamekeepers; the farmers, whose crops they destroy, may consider them predators or pests, but the birds are appreciated – at least by me. That dichotomy between the birds’ reputations – and the loathing they inspire – and their feathers’ physical beauty and value to me as an artist is a crucial component of the material’s fascination for me; that ability for it to be both one thing and another gives an extra layer of meaning to my work, making the feather a useful metaphor for the duplicity of nature, a theme that sits at the core of my work.

I feel very physically connected to my materials, perhaps because I spend so many hours cleaning and sorting them. I’ve realised down the years that the preparation time is as much a part of the creative process as the actual making. It’s while I’m handling the feathers that I’m able to reflect on the work(s) I’m about to make, giving me crucial thinking time before I commit anything to paper. The mind is a malleable canvas, while physical mistakes can be hard to undo.

The feathering stage is compelling, hypnotic; I can happily lose myself in it for hours. It’s also instinctual – you can’t plan how to lay the feathers out nor can you really teach someone. Each feather contributes to the overall patterning of a piece, and it’s this implicit sense of movement in the shifting colours and gentle curve of each filament that brings the work to life. This final stage draws on the rituals of craft, on the connection between hand and eye and the natural serendipity that happens when you become fully immersed in giving life to an idea. It’s my favourite part of the process. And because it makes me so in tune with a piece it makes the finished work hard to let go.

In the past twelve years I have lived or worked in London, Rio de Janeiro, Calgary, Montreal and now Angola. Each place has influenced my work both in the way it has made me reassess the importance/role of the digitised body and also the materials and processes I choose.

When I was in the UK I remember feeling that the dataset was something I wanted to master, control. In Brazil I found a freedom: the dataset became a vessel through which I could express myself. In Angola the dataset seems almost absurd, superfluous and out of place. I believe my sculptures and the materials and processes reflect these differing relationships with the ‘data body’. There is also of course the reality of the practical problems of transporting sculpture. When I was in Brazil I had to start thinking about how I could make works that could fit into suitcases. In Rio I was also able to have access to so many different types of materials because of the carnival supplies district. There was so much material pleasure to be had there that is was impossible not to use them in my work.

All my works are materialisations of datasets. I use technology to acquire the scans (MRI or CT scanners) and I use radiology software to process the data, image manipulation software to work the images I often use digitally mechanised machines (such as laser scanners/CNC machines) to produce parts of my work. I am very conscious however that I want to keep a balance between the digitally mechanised produced and the handmade so always try to match the amount of ‘work’ of the machine with the amount of work by the ‘work’ of the body/hand of the artist.

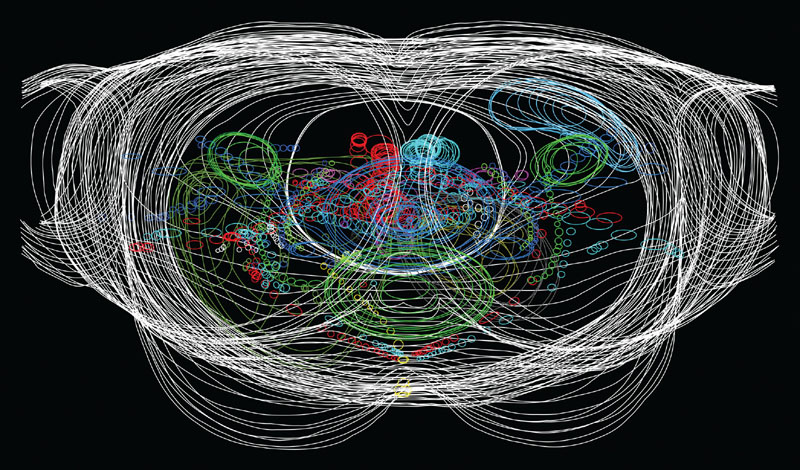

Digital map of the imagined scans of Leonardo’s Great Lady (made in collaboration with Dr Francis Wells), Marilène Oliver.

Split Petcetrix, 2010, Marilène Oliver. Foam rubber, seed beads. 85 × 80 × 35cm. (Photo: Todd-White Art)

I was born in a poor mountain village in China to parents who, as educators, were labelled political dissidents and forced to live a life of agricultural servitude and persecution. My childhood was oppressive with little dignity and security – we were often hungry and humiliated – this experience continues to mould my artistic practice today.

Ever since I started drawing in elementary school, I considered myself an artist because I could draw. I knew I was not the same as the other children running around in the neighbourhood or playing games together as I sought solace in art and in the quiet corners of our peach orchard.

The end of the Cultural Revolution gave me the impetus to become an artist and for many years I built up my reputation as a highly successful commercial artist. In 2002 I had a neardeath experience, which altered my priorities and perspective on life again, so I emigrated to the USA to focus full-time on my own practice.

My creative journey usually starts with a concept then I go out and search for my inspiration from humanity and nature. I am not searching for something I have already in my mind – it is more to embrace every view, every touch, every moment of humanity, every spirit of nature I encounter. I put this mixture of ideas and experiences into my mind, let it get cooked, tossed, smashed, refined, or renewed till finally a rough plan of my project emerges.

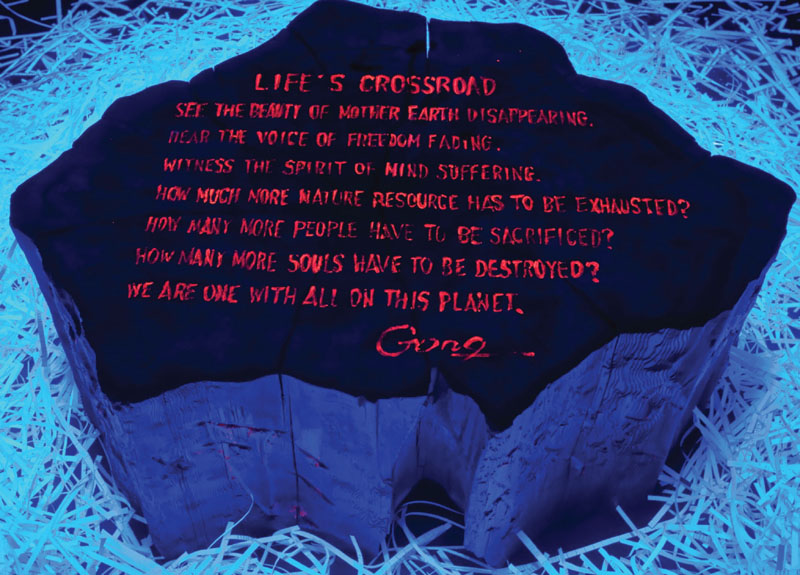

Installing Life’s Crossroad, 2010, Gong Yuebin. California Lutheran University, Thousand Oaks, California. (Photo: Michael Pearce)

Life’s Crossroad (detail) 2010, Gong Yuebin. Installation Gong Studio, Sacramento, California. Found burnt trees, steel plates, metal chains, acrylic paint, and fluorescent lighting. (Photo: Gong Yuebin)

As a child I was a dreamer. I was completely in a world of my own.

My mother used to ask me if I realized I was alive because I was always drifting in my thoughts. Perhaps my life was a dream and I would wake up in a parallel world after I died in this one.…

Certain events in my childhood had a profound impact on my choice of becoming involved in medical art. I must have only been about six or seven years old when my cat was killed by a car. I carried her into the garden and saw the life drain out of her eyes. At the same time as being very distraught at the loss of my cat I can remember being fascinated by the changes in her eyes when she died.

I was always pondering life, mortality and death. I was twelve when my grandfather died and I went to pay my last respects. I distinctly remember the stillness of his body and the absence of the rhythm of breath in his chest which frightened me and made me feel very claustrophobic.… My fascination with the human body, anatomy, disease and mortality grew as I tried to understand death – the absence of life in the body.

Science, and the physical mortal body was my first interest and the idea of developing it into an art form and communicating my philosophy slowly grew from there.

Confronting Mortality (work in progress), 2007, Pascale Pollier. Wax, mixed media. Life-size. (Photo: Pascale Pollier)

Pascale Pollier’s studio in Brakel Belgium. (Photo: Pascale Pollier)

I find it important to be able to work quickly, to formulate and capture my ideas and concepts in three dimensions… this is one of the reasons why I don’t like working in stone. It’s too slow.

I have always loved drawing with pencil, pen and charcoal as drawing is the direct connection of observations from the eye to the hand – taking direct notes from reality.

It was my struggle with colour intensity that first brought my attention to the condition of albinism. This was a major step in bringing my passions in art and medicine together. I studied medical art part-time for about five years in London – in dissection rooms, operating theatres and during autopsies I would draw, draw and draw. My research focused on endocrinology and the intersexual, and dermatology and albinism. I dug down deep into cell biology and went right down to the core, to the nucleus and the DNA while making drawings, taking notes and painting.

My first medical art sculpture was The Pigment Cell – this took me a year of hard, grinding work as every single organelle needed to be sculpted and cast individually. The sculpture was finished in clear resin and it took over 100 hours of polishing to get it as clear as glass. For this work I was awarded The Ronald Raven Barbers’ Award and the prize for the best entry to the exhibition of the MAA/IMI conference at Cambridge University 2000. After I graduated from the Medical Artist Education Trust I moved to Belgium and lived there for the next ten years. Here we found ourselves a house with a very large studio and this played an important role in moving me closer towards sculpture.

I worked for Gunther von Hagens when his exhibition Körperwelten was in Brussels for about six months. I made several drawings and even stayed there one night all night drawing the plastinates… I was literally living among the dead… as I hardly saw daylight at this time. In the catacombs of the abattoir, there was no natural daylight and in the morning, I could hear the squealing of the pigs before they got slaughtered, it was altogether quite an eerie experience. After the Body Worlds’ experience, I worked for a Dutch pharmaceutical company illustrating their online encyclopaedia.

In 2006 I organized a conference for European Medical Artists Associations – Confronting Mortality with Art and Science – it opened up a whole new chapter in my life and led to the formation of BIOMAB Ltd. Art Researches Science was also launched comprising of international collaborations to organize exhibitions, conferences, film production, dissection drawing workshops, and international exchange projects. During this time I realised that pure functional and educational medical illustration was too limiting for me and I wanted to broaden my practice to encompass art and science through sculpture. I am living back in London now working as a self-employed artist, artem-medicalis, I still have my studio in Belgium, The materials I work with include: wax, plastolene, sculpey, plaster, silicone, polyester, real hair, special effects materials, fake blood, glass eyes etc, el-wire, LED lights, pumps, medical instruments, plastic tubing, oil paint, psycho-paint and silicone paint.

MARK HOUGHTON

One Saturday night, I did not have enough money to go out drinking with my mates as usual, so I stayed in to watch television. By chance I saw Edvard Munch by Peter Watkins and that was it, decision made, be an artist. This really brought his work to life, and obviously all those psycho-dramas connected well with my love-struck teenage angst! I had always been good at art at school, but this film made me want to dedicate myself solely to that aim.

My father was an architect so I became very comfortable with the process of converting 2D drawings or images, into 3D objects, and understood the cerebral relationship between the two. I started as a painter, but always made paintings with very physical surfaces, often including 3D objects with wax or plaster. I became disheartened with painting – for me, sculpture was the art form that dealt most with reality – with physicality, real objects, real spaces. This gives it the edge for me over, say painting, or video, which essentially deal with illusion, and illusionistic space. Sculpture relates to the real world, to inhabited space, to the constructed environs we inherit and inhabit. For me it is a way of re-presenting aspects of the everyday, a way of making the familiar unfamiliar, so that we have to re-evaluate our relationships to the objects and spaces we encounter. It is a way of attempting to decode and decipher the complexity of the world we inhabit, and to try and make sense of all this stuff that surrounds us.

Research 2007, Mark Houghton (Photo: Mark Houghton)

I’m endlessly fascinated with everything around me. How are things put together, what are they made of etc., and this provides a lot of inspiration. Like most artists I am interested in finding alternative uses or interpretations for objects and materials, and don’t like to take things at face value. It comes back down to that questioning nature – what else can that something be or mean?

I believe very strongly in colour within sculpture, and always want it to be integral, rather than added. That way it feels more like another material in its own right rather than an additional afterthought, or surface decoration. I also try to choose materials that have an endemic colour, so they can be included and left untouched, in a sort of ‘truth to materials’ approach.

The use of another person or process can generate unexpected directions for the work, in the same way that painters like to generate accidents to respond to them. These types of processes can also be a way to unify a surface, and maybe even disguise how it was made. Sometimes I like the work to look as though it has been automated. It’s a way of removing the artist, of denigrating gesture, so that it has to be read less romantically, and it references the everyday, or the non-art environment more.

Drawing is not very important to me in the traditional sense. I used to draw an idea out before making it, but this felt like quite a dead process, as though I was illustrating an idea. If I make a very loose sketch, then the work has more freedom to develop during its creation. I have become more interested in that process of development, rather than the initial idea that began or informed that process. Also I found that if I drew an idea out carefully, I would lose interest in making it, as though I had completed the piece on one level at the drawing stage. I often look at completed installations though and they sometimes feel like drawings or painting that have exploded into space.

I have to document the work very carefully. Most of it exists temporarily, so the documentation becomes the currency that gets me the next show. One has to be realistic. Most people encounter my work through a jpeg on a web site, or through a digital image. Most of the art I experience is in the same format. I have worked as a photographer so this documentation aspect is not a problem, and as the work can often be very graphic, it is often very photogenic too.

Since 2009 I have been more interested in letting the work dictate its development, and it has been more about that developmental process, rather than the original idea that kick started that process. Looking back, constants do emerge: the use of found objects or materials and responding to something that I might encounter on a regular basis – something architectural maybe. I like the work to be very minimal, geometric, and have art historical reference. These are constants, or interests that have always been around and helped to inform the work.

I never really feel that a piece is finished as such – I prefer the term concluded. This feels more temporary as if there is room for subsequent future developments. I always run out of time when installing because I like to work in the gallery. I see this as just as important as being in the studio, and will develop the work as I install it, so if it’s still giving me ideas an hour before the opening, I will still be working.

Making site-specific responses at G39, Cardiff, 2011, Mark Houghton. Installing work for Arewenotdrawntoanewera? (Photo: Kay Williamson)