Latent Measures (Component 4), 2010, Awst & Walther. Installation Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin. Pigmented gelatine, aluminium. 88 × 250 × 19cm. (Photo: Damien Griffiths)

THE SOFT AND THE SENSUAL

Touch places us into the intimacy of things and of matter.

Jean-Luc Nancy On Touching,

Derrida J, Stanford University Press, 2005.

The Soft and the Sensual is reference to the art of material seduction by those substances that demand intimacy and palpation. Sculptors have long exploited these attributes to underline their commentary and the ones highlighted here are those who have excelled at this. Each has embedded a personal narrative in their sculpture through an innately powerful and unusual material palette.

Gelatine is explored with sculptural partners Manon Awst (UK) and Benjamin Walther (Germany) who explain their rationale for using the animal product and how through extensive trialling they have developed a unique minimal lexicon. Dorcas Casey (UK) has a passion for textiles and stitching – she reveals how she has developed processes to make textiles suitable for outside exhibition with the product Jesmonite. Mary Giehl (USA) discusses using soap as a means and a metaphor and her experiments with sugar, while YaYa Chou (Taiwan) talks about her reasons for making assemblages from sweets.

GELATINE INTERFACE

Gelatine is a protein product with attributes of translucency and flavourlessness. It is derived from the partial hydrolysis of collagen extracted from the skin, boiled crushed horn and bones, connective tissues, organs and some intestines of animals such as cattle, chicken, pigs and horses. It is commonly used as a gelling agent in the food, pharmaceuticals and cosmetics industries and is available in sheets, granules, or powder.

METHOD FOR MIXING SMALL QUANTITIES OF GELATINE

RECIPE

2 parts crystal or powder gelatine

2 parts glycerine

1 part liquid honey

1 part warm water

Pour the warm water into a microwave-proof plastic container – gently stir and dissolve the runny honey in the water.

Add the glycerine and place the container in a microwave for 20 seconds to warm it through, but not boil it.

Remove the mixture from the microwave and stir in the gelatine – mixing very thoroughly.

If the constituents are not blending smoothly then return to the microwave for short periods and stir intermittently. Monitor the mixture carefully as it must not boil.

Put the gelatine mixture in the freezer to cool it rapidly.

This is a readily available mix that is suitable for a wide range of applications however please note that it is advisable to experiment with the recipe to achieve different properties.

Making Latent Measures (Component 11) 2011, Awst & Walther. Installation Hannah Barry Gallery, London. Gelatine, pigment, aluminium pole, plywood, nails. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Manon Awst)

Sculptors Awst & Walther explain the attraction, ‘Gelatine is a pure protein and that really excited us – it represents strength and structure, yet it has an inherent vulnerability through its materiality. It has a very shiny, glossy surface when it’s cast and is quite reflective, so there is an element of narcissism to it.’

Gelatine is generally considered a user-friendly, non-toxic product, plus it is cheap, stores well and is easily available. In addition it can be melted down and re-used. There are no significant health and safety concerns for handling gelatine, just follow normal studio/workshop safety practices.

Awst & Walther used large quantities of pigmented gelatine in their Latent Measures series. Initially, the gelatine mixture was created in manageable amounts, then cooled and stored. Lined timber moulds were built in situ. The pre-made gelatine ‘plugs’ were slowly melted back to liquid in large steel pans over a mobile hob – for sequential pouring into the moulds.

THE DRAPERY OF CLOTH

There are many arts practitioners who use cloth in their armoury but few are able to transcend its domestic references. In the 1960s Claes Oldenburg challenged the viewer with a collection of humorous sculptures made from textiles and soft vinyls. His remit was to celebrate the minutiae of life by consciously subverting the scale, material and character of the everyday object. Oldenburg explored a soft/hard dichotomy with monumental sculptures of an eclectic range of items – the objects were often mirrored in soft form by a canvas skin stiffened with resin. Contemporary sculptor Dorcas Casey explores this same journey of transformation.

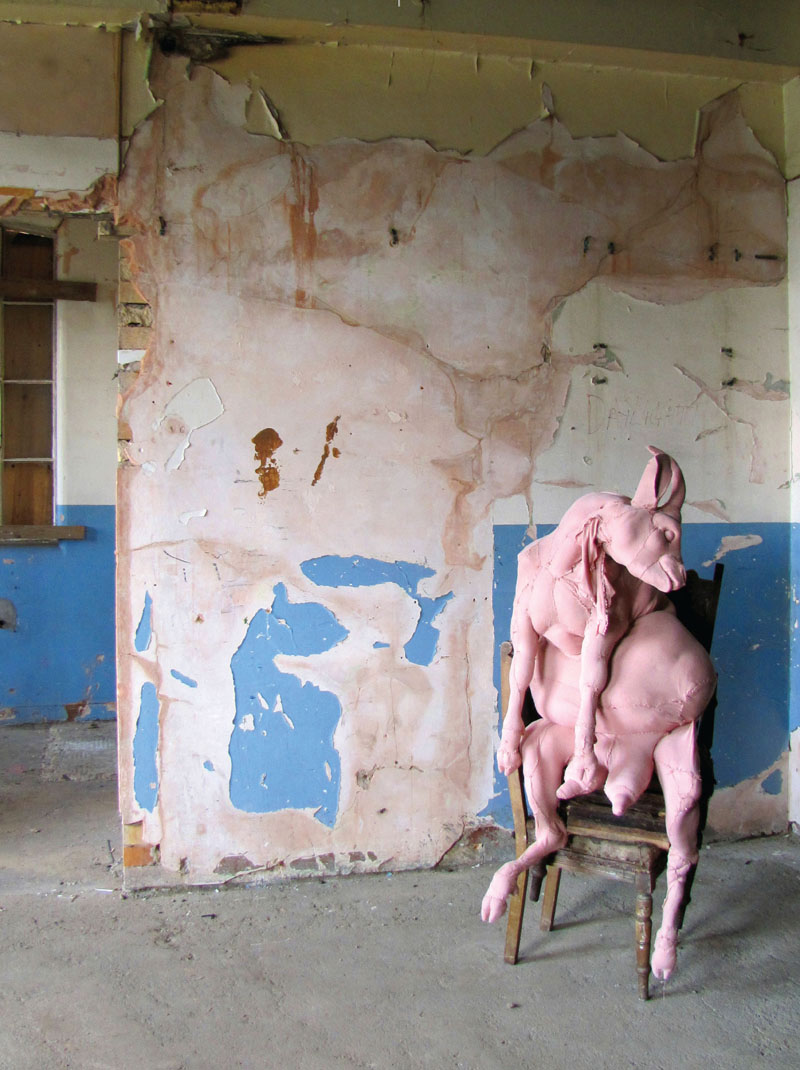

Goat, 2011, Dorcas Casey. Hand-stitched found fabric, stuffing, polymer clay, tape, rope, wire, old furniture. 120 × 100 × 80cm. (Photo: Dorcas Casey)

Goat (work in progress), 2011, Dorcas Casey. Hand stitching found fabric over polyester stuffing. (Photo: Dorcas Casey)

Fabric is a material I return to again and again. It has so much to offer. I like its potential for low-tech, unsophisticated methods of construction, which keep me close and involved with the piece I am making. Also I value how it naturally alludes to the human body like a second skin; objects covered with it seem to become human in some way. It is tactile and familiar, and I am interested in its nurturing, comforting connotations. Fabric lends itself to transformation into anatomy. Its elasticity mimics sinews. It flexes and moves like a body, and stretches, folds and sags like skin.

Dorcas Casey in conversation with the author, 2013.

Casey’s oeuvre has a dynamic duality where she deliberately showcases the handmade elements in her sculpture such as stitching, to intensify the conceptual message, but is still able to elevate the work to stand among more traditional techniques.

For me, the construction of something very particular, deliberate and laborious-looking is important. The process is visible. I want it to be apparent that my sculptures are made from bits and pieces of the ‘everyday’ and reassembled into something uncanny and powerful, like a dream image. I like there to be beauty in the construction. In my sculptures the construction method also often forms the surface of the work. I design and get ideas during the making process and my sculptures evolve very organically.

I frequently use hand stitching in my work. It’s an obvious way to join fabrics, clothes, and leather but there also a history to the stitch. The action of stitching feels very ‘old-fashioned’, it feels like it connects me to past generations. The needle is such a tiny and simple tool. It’s very humble. It can be nurturing or aggressive. I like its association with mending, darning and comfort but also its more macabre connotations of suturing, taxidermy, and surgery. There is a lot of potential for gesture within the stitch as opposed to other ‘seamless’ methods of joining materials. I prefer to use meticulous, neat, hand stitching, I like the suggestion of repetition and obsession it projects and the thought of the tiny movements of the needle accumulating to build up a substantial object which has heft and magnitude.

Dorcas Casey in conversation with the author, 2013.

Familiar (work in progress), 2013, Dorcas Casey. Coating secondhand bedding and clothing with Jesmonite. (Photo: Nic Heal)

Familiar, 2013, Dorcas Casey. Secondhand bedding and clothing, Jesmonite, wood and steel armature, concealed concrete base. 250 × 70 × 70cm each. (Photo: Jasper Casey)

The conflict of the lure of soft drape versus the strength of the rigid form has been resolved by Casey by using the excellent properties of Jesmonite to transform her languid forms of cloth into robust, dynamic creatures able to withstand the outdoors. The result captures the movement and texture of the cloth while becoming resilient to exterior conditions. There are various types of Jesmonite suitable for different applications – the product Dorcas Casey uses for her sculpture is AC100 as it is designed for casting and laminating and is robust enough, if sealed, for exterior siting. She says, ‘I’ve used both wool and acrylic textiles and I prefer acrylic as I find the detail and texture in the synthetic fabrics shows more clearly than that on wool when soaked with Jesmonite. Wool has a lot of stray fibres on the surface, which the Jesmonite clings to, obscuring the texture.

‘When I soaked the blankets to make the draped fabric ‘bodies’ for Familiar I used between ten and twelve kilos of Jesmonite per blanket which when added to the weight of the blankets (some of the thicker ones were already quite weighty) was really heavy and unwieldy to handle. I needed an extra pair of hands to lift them into place and position them so that they set in the right shape.’

Jesmonite is a proprietary acrylic polymer and calcium carbonate composite product that raises few of the toxicological concerns that traditional resins do. It was primarily developed for the construction industry to rival polyester and polyurethane resin systems, but without the ventilation and clean-up requirements. It is available in four formulas each suitable for different applications. Jesmonite is useful as a sculpture material as its dimensional stability enables it to be used at any scale with little problem with expansion.

General Method of Mixing for all Formulas

Jesmonite comes in two parts: liquid and a powder.

Using a high shear blade attachment on an electric drill combine the two ingredients in a large bowl or container by adding the powder to the liquid and mixing continuously. Make sure all the lumps are removed but avoid over-stirring which can cause unwanted air pockets.

Add a thixotrope to the mixture if you want a thicker gel consistency. Refer to the manufacturer’s guidelines for correct ratios. The suppliers also sell a retarder that can be added to the liquid to extend its ‘pot life’.

Laminating with Jesmonite

In lamination, the aim is to create a sandwich of reinforcing materials, Jesmonite and the original object/matter.

Specialist suppliers sell a range of suitable materials for reinforcing including: chopped glass-strand matting in bi-axial and multi-axial versions and woven and continuous strand options. Saturate the material with the Jesmonite mixture unthick-

ened.

Layer the reinforcement matting on top and brush through with unthickened Jesmonite.

Thicken the Jesmonite and brush on to the ‘sandwich’ aiming to for a 2mm-thick coat.

Apply a second layer of fabric reinforcement matting and saturate with Jesmonite.

GENERAL TIPS FOR USING JESMONITE

Silicone moulds do not require a release agent however, cold cast rubber and rigid moulds such as timber will need a coat of release wax applied with a soft cloth prior to casting.

For casting in moulds apply a brush coat on the mould before pouring the Jesmonite – this will help to minimise trapped air.

Gently vibrate the mould to remove air pockets.

For a stronger form, layer the sculpture with appropriate glass matting reinforcement material, whether casting or laminating, as this makes a significant difference.

The compound has a fast cure rate – the chemical reaction is over in around an hour after reaching 30°C. It achieves 60 per cent of its ultimate strength and has approximately 5 per cent water retention after an hour – the aim is to dry the compound out to about two per cent to achieve maximum durability. Place the piece in a warm, dry environment, with air circulating, to assist the process.

As it is a water-based composite you can clean the equipment with water before the product sets.

Jesmonite is solvent free and fire resistant.

There are no significant health and safety concerns for handling Jesmonite, just follow the usual studio/workshop safety practices.

Exterior

Two coats of sealer brushed/sprayed on the sculpture should provide a protective coating. Its appearance when dry will be clear with a satin finish.

The first coat can be watered down by 50 per cent to enable better penetration.

Interior

To minimize marking during exhibiting and to achieve a matt finish, apply one coat of diluted sealer by brush or spray. The sealer can be watered down by 75 per cent. Add pigments to the sealer for a colour-washed effect.

SOAP SENSATION

Soap is not usually considered to be an art material but some notable exponents have created significant artworks from it using its soft texture and vulnerable surface to act as metaphor. Meekyoung Shin (Korea) is inspired by museum artefacts – she creates classical marble-like statues from soap – her most poignant is Crouching Aphrodite. Shin kept the traditional pose, but reinterpreted the goddess’ features to evoke her own Asian origins to challenge the notion of classical feminine beauty in many historical statues. While, Janine Antoni (Bahamas) in her Lick and Lather series, created sculptures from soap and chocolate to comment on the rise in eating disorders in women.

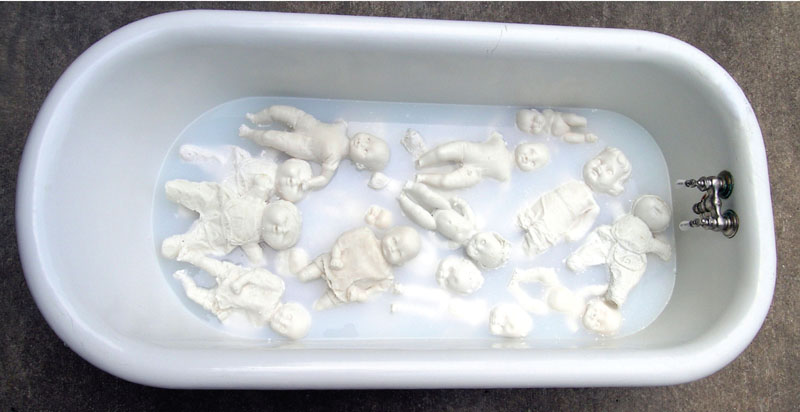

Ivory (detail), 2007, Mary Giehl. Installation Everson Museum, Syracuse New York State. Thirty soap dolls in cast-iron bath of water – after one week. 184 × 79 × 61cm. (Photo: Mary Giehl)

CASTING IN SOAP PROCESS (PREFERRED BY GIEHL)

To cast the dolls Giehl first created a plaster negative mould around each doll, then built a positive two-part rubber mould inside. The mould was left open at the feet end so that the soap mixture could be poured inside. She made her dolls using equal proportions of soap, paraffin wax and glycerine. She melted the chemicals together, mixed them thoroughly, then let the mixture cool till it was pourable. After pouring carefully into the moulds the dolls were left to cool for around twenty-four hours.

Mary Giehl has also developed a body of work using soap as both the means and the metaphor. The artist has fond memories of her own joyful baths with her brothers but she realises that this activity can sometimes possess a dark side, as the installation Ivory negotiates. Multi-sensory, its impact is intense and haunting, past its initial engagement. Three castiron baths are filled with distilled water and more than 100 dolls cast in soap from moulds of discarded toys. The dolls gradually dissolve in the water – drowning slowly over a fourmonth period. The water evaporates and the liquid turns to a gelatine-type solution.

SUGAR RECIPE AND METHOD (PREFERRED BY GIEHL )

1 measure sugar

½ measure water

1/3 measure light corn syrup

1/8 to ¼ teaspoon candy flavouring oil

Food colouring as desired

METHOD

Mix the sugar, water and syrup in a lightweight pan over a medium to high heat.

Bring to the boil.

Add a candy thermometer – cook to the ‘hard-crack’ stage – usually 300°F.

Remove from the heat.

When the bubbles simmer down, stir in the flavouring oil and the liquid food colouring to the required colour strength.

Leave to cool to 275°F, then pour into the mould.

TIPS FOR CASTING WITH SUGAR

Too much candy oil will spoil the process.

Spray the rubber mould with silicone before casting to help release the sugar objects.

The object will be delicate when set – it is vital to leave it to cool completely to avoid unnecessary breakages.

The sugar objects gradually loose their transparency over time and after about two months may melt. Isomalt sugar substitute may help to avoid these negative reactions to humidity.

The outcomes are not suitable for consumption unless you use the appropriate specialised silicone moulds.

SUGAR RUSH

Sugar and water may seem unexpected materials to use in sculpture but some sculptors find its unique attributes seductive. Vietnamese artist Richard Streitmatter-Tran created a giant Buddist temple made of sugar for the Venice Biennale in 2008 and Northern Ireland’s Brendan Jamison continues to build copies of landmark buildings and structures such as, Bangor Castle, Tate Modern, Eastborne Tower and The Great Wall of China, from sugar cubes. Mary Giehl and YaYa Chou both find the associations of sugar relevant for their sculptures and the material’s properties ripe for manipulation into works that entreat and confront.

In 2007 Mary Giehl was attracted to the attributes of sweets associated with infant characteristics and how through manipulating a candy recipe she could create 3D forms. Casting a collection of old children’s shoes in her candy mixture the installation Sweet was developed. The brittle nature of the candy meant a high percentage of the cast shoes were shattered on removal from the rubber moulds. Once displayed, the sugary footwear gradually degrades over time as the candy reacts with the humidity – it melts and dulls, metamorphosing into an unappealing sticky mess. Giehl believes that the process resonates with the dysfunctional lives of some children.

Sweet (detail), 2007, Mary Giehl. Installation – SOHO 20 Gallery, New York. Sugar, water, food colouring, paper towels. 28 × 30 × 13cm. (Photo: David Broda)

Sugar Assemblages

YaYa Chou employs the connotations of cheap confectionary to make social comment on USA culture: the disparity in affluence, the creation of a nation of obese children and their alienation from nature. Gummy Bears sweets are primarily made from tartrazine, a coal-tar derivative, often used as a low-cost food additive and colourant. Tartrazine has a well-documented long list of ill side effects when eaten – it is a favourite snack eaten by many children in the USA and by Chou herself before she researched the product. Beta-carotene is a natural and more healthy alternative, widely available but costing significantly more. The socially deprived are the primary consumers of this candy so Chou elected to make social and political commentary on the wide fiscal gaps in American society by making the pieces in forms associated with the affluent. It took Chou two months to complete making Chandelier – thirty pounds of Gummy Bears had to be threaded onto monofilament. Two years after widespread exhibiting of the piece it is still intact – neither insect nor mammal has been tempted to gnaw – further illustration of the ingredient’s artificial composition.

Chandelier (detail), 2010, YaYa Chou. Gummy Bears, beads, monofilament, CF bulbs, metal and mixed media. 114 × 53 × 53cm. (Photo: YaYa Chou)