Home: 3 bed-semi, 2013, Jac Scott. Three discarded rusty mattresses and five abandoned bird’s nests. 50 × 65 × 60cm. (Photo: Rob Fraser)

THE SCULPTORS

Sculpture is the chorus for waking and the drug for sleeplessness.

Jac Scott, 2013.

JAC SCOTT

In my own practice the focus is on creating issue-based work that investigates the environmental issues behind fractured realities. My preoccupation lies in exploring the enigma of our existence, revealed in our ways of being, our relationship with our environs and the marks we leave behind. The aim is to have an oblique potency that acknowledges the world’s dark underbelly, while acting as a catalyst for igniting debate. The foundation is underpinned by the questioning of those issues that drive a world without a sense of equilibrium.

As an innate researcher I have not lost that child-like curiosity and wonder about the world – taking risks and confronting boundaries both in concept and materials are endemic. The emphasis on research and questioning has avoided a myopic narrative, delivering an informed dynamism that maintains freshness in my practice.

The fabrication of ‘stuff’ poses a conundrum in that as a sculptor while I create, I also wish to reduce the amount of ‘things’. Consequently, part of my quest is to reduce and reuse, which demands some innovative use of ‘finds’. The work is intensive, saturated with cognitive battles juxtaposed against searches for harmony with incongruous matter. Hence, it requires a significant amount of experimentation, analysis and evaluation.

Collaborating with scientists and geographers is the mainstay of my work – to investigate the notion of ‘manscape’ – humanity’s illusion of the naturalness of the environment. Man’s mark on the planet is extensive, explicit and acknowledged, but our embedded sense of reality belies the true depth of our impact. This concept is explored in the Beautiful Dystopias Collection where the relationship between contaminated environs and the anthropocentric compass is examined. This mapping of the hidden impacts on the planet has dictated the re-examining of the commonplace – a cognitive reconfiguring of the ‘common ground’ we all share. Both as metaphor and in material selection, my artistic response focuses on brooding degradation: peeling layers inviting a meditation on the narrative exposed.

It is appreciated that our ways of being are often revealed in our relationship to our environs and to each other, and that the symbiosis is fragile and temperamental. My work aims not to offer a panacea or judgemental retort, (we are all culpable), but to investigate the inter-connectedness of humanity and the environment through exploring the less visible imprints. We fail to recognise our impact on even the simplest land and seascapes, often perceiving ‘wild’ places as unmanaged and natural. There is nowhere on our planet that has not felt the hand of man, even those expansive terrains known as wildernesses, such as the boreal forests and the central deserts, are subject to an anthropocentric pulse. Man stands aloof from nature, surveying the Earth as a resource to be devoured and exploited, ignoring the dynamic undertow.

In my Home series I question the idea of home as a place of refuge from the outside world and, paradoxically, if the world is home to our species then where is the refuge?

Atomic Equilibrium, 2013, Jac Scott. Old wooden picture frame, found discarded door lock, hand forged nail. 20 × 36 × 16cm. (Photo: Rob Fraser)

A home does not simply specify where you live; it can also signify who you are (socially, economically, sexually, ethnically) and where you ‘belong’ (geographically, culturally). And a house or a dwelling is full of the occupant’s corporeality, of sleeping, eating, loving: of its existence as a home. Moreover, a house contains evidence of the intimate relationship between space and time. While the space of the constructed building may shelter people or families over long periods of time, the evidence of more transitory individual lives is visible in traces in and on the building and its furniture. These ‘traces’ may take the form of damage, dirt, dust, decorations, scratches, repairs and so on.

Extract from Gill Perry ‘Dream Houses: installations and the home’, Themes in Contemporary Art.

Applying this idea of home, as described above in the quote from Gill Perry’s ‘Dream Houses: installations and the home’, but to the Earth, rather than a building, invites a new perspective on our custodial duties.

The Earth is home not only to us, but also to many other organisms – it provides the right elements: atmosphere, temperature, sustenance and time, for us to prosper. Sustaining a world with a sense of equilibrium towards these fundamentals and appreciating the interconnectedness of them all is vital for our home to flourish.

I created Home: 3 bed-semi from three discarded mattresses I found washed up on the beach. The waves had ravaged the upholstery leaving a tangled web of rusting and flaking metal armatures. Salvaged, the mattress cores were crushed and compacted into a cuboid by a baling machine in a scrap metal yard, normally used for condensing old metal cans into bales ready for recycling. The spirit of the springs, now largely tamed, was further restrained to prevent the metal’s memory returning.

Five fragile birds’ nests rescued from local hedges in midwinter adorn the ‘bed’ and remind us that a shelter is temporary if not nurtured.

In Beautiful Dystopia the concept of dystopia is considered – an illusionary perfect world where Authority maintains its totalitarianism through systematic discrimination that is geared to enforce its doctrine. Political oppression, blatant bias, a fear of the outside world and a mistrust of the natural is instilled in the dystopian society to control dissent and individuality. The notion of a dystopian society is considered a futuristic notion but this work questions whether our relationship to the planet suggests otherwise.

Home and Away, 2013, Jac Scott. Found rusty mattress, antique mahogany floor lamp, antique brass birdcage, spray paint stencilled birds on wall. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Jac Scott)

Home and Away (detail), 2013, Jac Scott. Installation PR1 Gallery, Preston, UK. Found rusty mattress, antique mahogany floor lamp, antique brass birdcage, spray paint stencilled birds on wall. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Rob Fraser)

Beautiful Dystopia, 2013, Jac Scott. Polymer plaster, recycled glass, found metal rod and pipe, abandoned blackbird nest, paint. 25 × 130 × 50cm. (Photo: Rob Fraser)

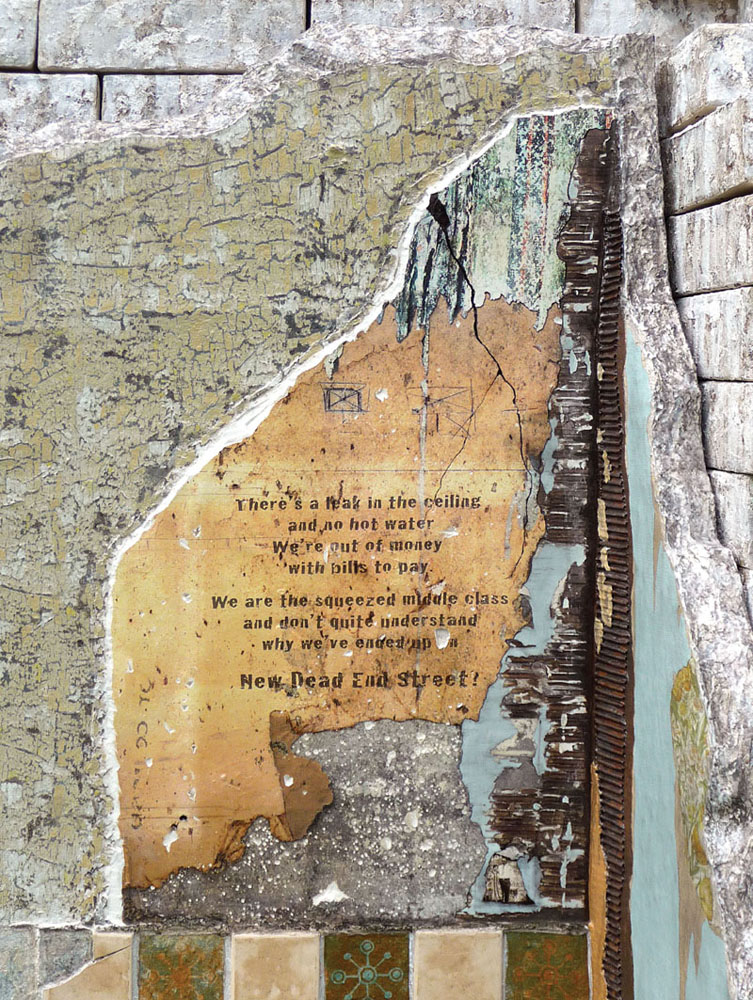

Book of Revelations is a series of wall-based sculptures that aim, through a dishevelled mourning incarnate, to silently contemplate the fractured reality we have created. The peeling layers invite a meditation on the narrative exposed, while the found objects transpose and complicate the space from painting towards sculpture – settling in neither. The brooding degradation is juxtaposed against the unsettling extravagance of the golden frame.

Our view is framed. The duality of being is that we seek the security of frameworks in our lives while remaining curious about the wider world. Science and art inform and nurture our quest for expansion to the physical and metaphysical worlds we inhabit. The magnitude and monumental narrative of the planet ignite wonder yet conversely endow a sense of insignificance to mortal man.

Harnessing the redundant golden frame as a symbolic border, one that demarcates the contents as worthy of being luxuriously wrapped, the sculptures present artefacts dislodged from our focus of possession. The discarded, retrieved and redefined objects are imbued with metaphor and meaning. The damaged frame, holding fragmented spaces while clinging to the precious cargo, defies the loss and reveres its ostentatious past. Metaphorically, the frame highlights the paradoxical interconnectedness between destruction and renewal, past and present, consumption and disposal. The fractured structure signals the frailty of the framework as an illusion of security.

The eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility.

Einstein, A., Physics and Reality, Journal of the Franklin Institute.

Book of Revelations: Mankind, 2013, Jac Scott. Antique mahogany easel, discarded gold frame, plaster, paint, cloth, broken mirror, old spectacles, human hair. 96 × 67 × 6cm. (Photo: Rob Fraser)

Bio Myopia (detail), 2013, Jac Scott. 38 × 23 × 19cm. Found road tar, discarded metal rod, glass test tube, seabird skull. (Photo: Rob Fraser)

Site 2801, 2012, Gong Yuebin. Installation California State University, Sacramento. Clay, fibreglass, flower petals. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Gong Yuebin)

The artist’s message is a key for the audience to open their own door to experience the sculpture in 360 degrees.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

Gong Yuebin creates haunting, poetic installations of monumental proportions, both in concept and in scale. His ambitious works pose searching questions about life, death and the future for humanity. Informed by his difficult childhood in China during the Cultural Revolution, Yuebin’s artistic responses are emotional statements about his experiences and beliefs. He recalls:

I was born in one of the poorest mountain villages of China. Because I came into this world with marks of condemned status, children of landlords and antirevolutionary, throughout my childhood memory, I had no part in anything to do with other people. The peach orchid in the backyard and the little hill behind my home contained my entire childhood. Whenever it rained, big chunks of soil eroded away so fast as if the hill was disappearing in front of my eyes. Other children would run home. But I always charged up to the top of the hill and covered the soil, to protect it with my small body, from the big raindrops. When the rain stopped, I would look at the soil that had been washed away and cry.

Extract from artist’s statement, 2009.

In his work Life’s Crossroad, Yuebin identified the charred remains of a forest fire as symbolic sentinels of the human condition with regard to life and death. This, his first installation of epic proportions created from borrowing massive dead trees from the Sierra, USA, was executed in 2010, and marked a clear and new direction for the artist. Materials that for him captured the essence of humanity and nature, in their very corporeality and substance, now superseded his passion for traditional Chinese painting. This haunting installation was composed of salvaged burnt-out tree trunks painted with phosphorescent red paint and draped in chains. The colour was deliberately chosen to convey both shock and warning. To underline the tension and foreboding, the pieces were lit using black lighting in which the blood-red paint ominously glowed. In its echoing of the burning embers, the pervading atmosphere of Life’s Crossroad was eerily laced with a sense of otherness.

Several thousands years of human history shows the ruthlessness of human beings, not only towards its own species but also toward all forms of life in this world. I believe that someday humans will apologize for the lives that have been cut short. I believe that in addition to the lives of our own species, there are more important life forms in this world that sustain our present and future lives. Life goes on in everything and should be sustained. Life and death is intertwined.

Gong Yuebin, Sacramento, 10 February, 2011.

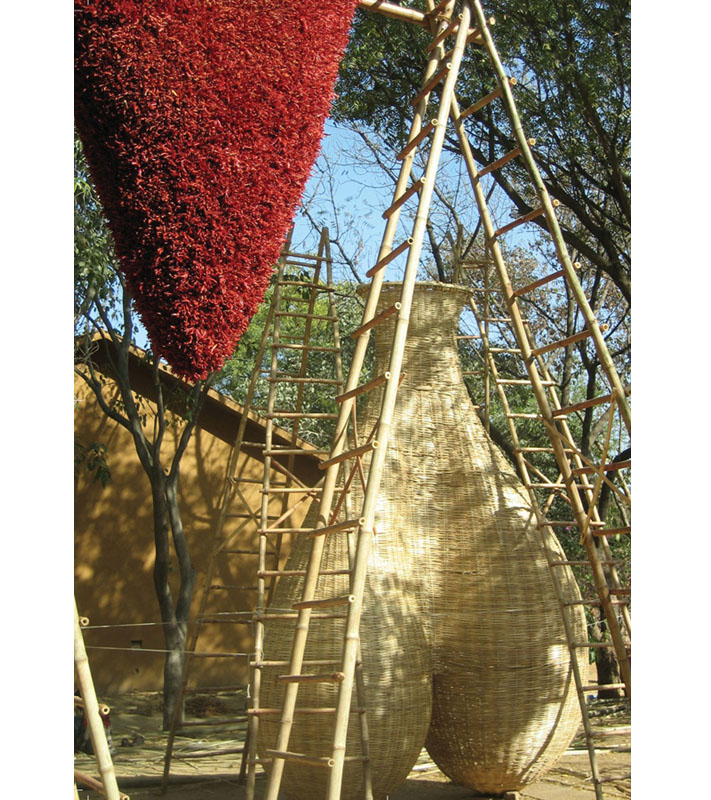

A sense of a dystopian vision is present in his installation Site 2801 where he entreats the viewer to become a ‘future archaeologist’. His inspiration was the site where the famous Terracotta Warriors and Horses of Xi’an, China (the funereal army of the first emperor of the third century BC) was discovered by a poor farmer in 1974. Two hundred replica warriors, made by Yuebin in Xi’an in the traditional way using terracotta clay, form the main component to this work. The army of statues include twenty modern terracotta combat troops hidden in the ranks carrying four disintegrating nuclear missile casings. The weapons of mass destruction, although presented as deteriorating, cradle giant new-born babies adorned with ancient faces, coloured blood-red, lying naked inside the missiles. Symbolic of future generations, the vulnerable infants evoke moral deliberations for the onlookers. This is Yuebin’s aim – to take the viewer on a transformative journey across time, while posing questions about the potential aftermath of our actions and how we have a chance to change.

Life’s Crossroad, 2010, Gong Yuebin. Installation Gong Studio, Sacramento, California. Found burnt trees, steel plates, metal chains, acrylic paint, and fluorescent lighting. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Gong Yuebin)

Site 2801 (detail), 2012, Gong Yuebin. Installation Crocker Art Museum, California, USA. Clay, fibreglass. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Gong Yuebin)

The delivery intensifies with ambient lighting that creates a lugubrious mood, reminiscent of a crematorium, while poignant white flower petals are offered to visitors who are invited to join the morbid drama and to solemnly toss them across the bodies at the ‘funeral’. Yuebin comments on Site 2081 in Sacramento 10 February 2011:

White floral petals and a maze of white curtain walls illuminated by ghostly florescent lighting surrounded and filled Site 2801. In this macabre setting the historical drama takes place, through enactments of moral contradiction and human tragedies: asking why we must destroy life to preserve life.

Symbolic white rose petals, made of silk, formed ritual offerings to the dead as visitors gently threw the petals at the scene of pathos, and thus participated in a mock funeral that transcended time and space. This formed a symbolical bid of eternal farewell to the most powerful of all ancient armies, the most destructive and deadly of today’s weapons, and also to the infants that represent our ardent hopes for an uncertain future. Through these ritual gestures, can we bear witness to history’s endless and tragic wars, or hear the painful and anguished cries of the victims? Can we still rationalize that past wars were of necessity and justice, rather than admitting that all wars are promulgated through conspiracies of greed and hatred? As we find more efficient ways to maim and kill, should we still claim to be members of advanced civilizations? And what is the value of a human life when it is reduced to a target inside the crosshairs of a gun, or to a mere blip on a computer screen? Perhaps the descending phosphorescent white petals, tossed by concerned viewers, will help us bury our atrocious inhumanity.

With sculpture one can create the illusion of life, which reflects the fact that life as we see it is an illusion anyway.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2012.

Pascale Pollier creates poetic 3D renditions of anatomically referenced ‘body maps’ that celebrate human life and death. The immediacy of the subject matter and her ability to capture realism provoke reactions ranging from quietly unsettling to outrage. Her work is not for the faint-hearted – its honesty in its clear intent confronts all who gaze at the wonder of the human form in its various states of undress – shedding clothes or skin.

THE QUICK AND THE DEAD

Mortal flesh and bone with benign fleeting soul composed grief-stricken structure I doth require your disengaged frame, your relinquished mould before this beautiful perfection mingles moist turf and oak and throws of graveyard soil many brights have wrought and eyed upon thee and chalked eternal masterworks from thee bequeath therefore your strange intriguing tenements of clay to medic shaman and artist and behold as absolute awaits.

Pascale Pollier, artist statement, Confronting Mortality with Art and Science, Vubpress, Brussels University Press, 2008.

These extraordinary sculptures incubate familiar narratives with resonance of Ron Mueck’s work, but unlike Mueck, Pollier approaches from a medical science perspective. This guides dissection of our understanding of this mortal coil with disembodied realistic axioms. Pollier embraces philosophy, psychology, anatomy, art and alchemy in her practice. She states:

My work is an attempt to capture the point where art and science meld. An alchemist at heart, I begin with observation and experimentation but my process of creating is steeped in solid scientific research and findings. My inspiration is drawn from observing the internal and external human body in all its diversity, strength, immortality, fragility, disease, mortality and death. New technologies and philosophies, quantum physics, Nano technology, animatronics are my muses and are important in my work.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2012.

Confronting Mortality, 2007, Pascale Pollier. Wax, mixed media. Lifesize. (Photo: Ingeborg Van Dooren)

In 2007 Pollier was commissioned to create a sculpture for the Antwerp conference Confronting Mortality with Art and Science. Her response was a life-sized wax model where the figure is only half-clothed in skin. The figure examines his own muscle fibre while contemplating his own mortality. Confronting Mortality entwines humour with a gentle morose curiosity that coaxes the viewer to edge nearer. The work, made from wax, is highly realistic and shows Pollier’s exacting making skills and accuracy at depicting the human form. These abilities were harnessed by plastinator Gunther von Hagens for his Body Worlds exhibition.

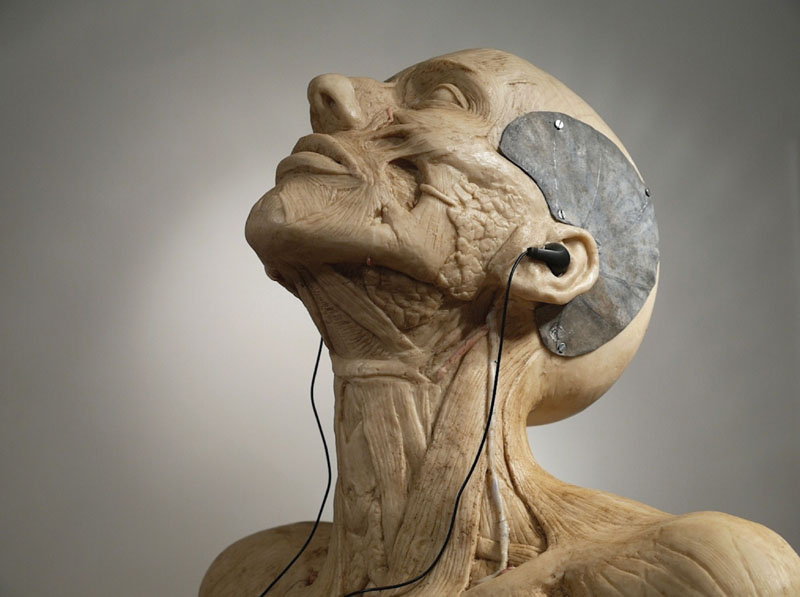

The concept of unwrapping skin to expose the vulnerable self was further explored in the autobiographical sculpture Female écorché. Pollier explains:

This sculpture, which portrays myself as a flayed female, is showing the strength and fragility of the human body. When one is naked one reveals the vulnerability of the self and the ego, but when stripped of skin one exposes a human vulnerability. Still, the woman stands strong, although communication has been interrupted, which is a sign of our times. Integrated into the digital, she is wearing headphones and is gazing upwards so no eye contact is possible. She has the headphones wired to her heart, thus she is tuned in to her emotions.

Extract from the artist’s website, 2013.

In Tesla’s Angst: A Tragedy of Errors, a fragile, deformed newborn baby lies with its placenta still attached in a rudimentary cot. For Pollier, the baby is symbolic of mankind’s self-determined troubled future and the placenta a disintegrating planet Earth – from its core a sound of the Geiger counter, detecting radioactivity, is heard. Eerily intense and disturbing, Tesla’s Angst: A Tragedy of Errors delivers a compulsion for contemplation.

The foetal motif is expanded in APGAR Score 3 With Aggravated Nervous System, where an adult male lies with his umbilical cord attached to a painted placenta. His back reveals the exposed nerves of his spinal cord; the sculpture references birth, death and the mortal coil.

Belgian-born Pollier has a truly European practice, but her focus is on universal themes – in the lugubrious History of Hurt I, II and III, she considers the narrative of global angst and suffering from various perspectives. In History of Hurt I, an open heart, newspaper, magnifying glass and a range of medical instruments are orchestrated to create a tension between the victims and voyeurs of world tragedies. In II, mummified hands clasp barbed wire in exasperation at the loss of hope and in III, the kneeling legs of a child at prayer address the ruination of innocence.

STILL HERE

The man in a white stillness zipped up encircled with nervous energy opponents the motionlessness serene absence of movement, moving us so deeply the non beating of the heart making ours skip faster than ever. Limb by limb removed brought us together the afterbirth indeed emotions pouring out like the wrinkled soft pink skin curtain dripping clear red yellow orange deep greenish blue. like the light shining through the melancholic afterbirth lyrical dark hue we are still here.

Poem by Pascale Pollier, 2010.

Female écorché (detail), 2009, Pascale Pollier. Wax, polyester, lead, headphones. 190 × 70 × 35cm. (Photo: Eleanor Crook)

… balancing the beautiful and brutal, the transcendent and abject.

Extract from artist’s statement, 2013.

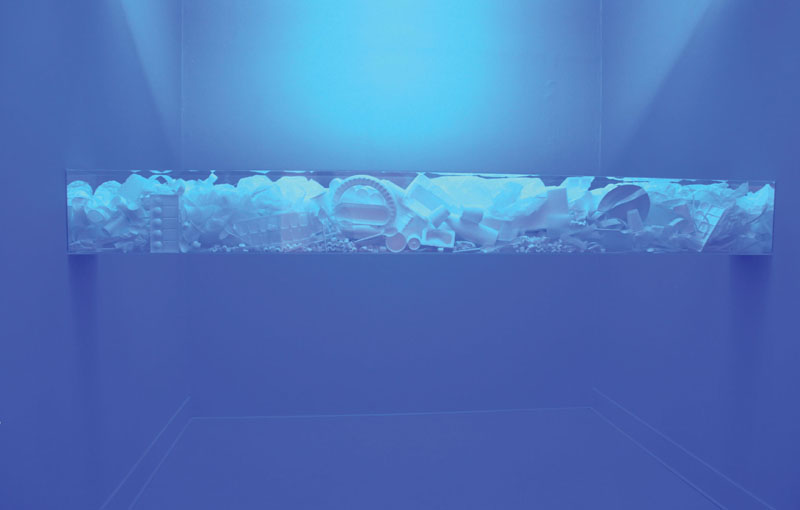

Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva has a truly unique artistic practice, focusing on transforming animal detritus that traditionally repels and disgusts into beautifully crafted artworks that intrigue and delight. Famous for her unusual gamut of materials and her intense research methodology, she develops innovative processes to invoke a fascination for transient phenomena. Hadzi-Vasileva’s palette truly expands the language of sculpture, as her artistic discourse is with matter that most artists would shy away from – caul fat (the thin membrane that surrounds the internal organs of cattle), omasum (cow’s third stomach lining), rat skins, silkworm cocoons, fish skins, and bones from fowl and rabbits; plus the more acceptable but still adventurous – rice, butter, watercress, fir cones and trees.

One of the reasons I enjoy working with the materials I choose is that they challenge presumptions or limited perspectives of what art can be and how it can engage other issues. They also question what can be beautiful.

In conversation with Lauren Meir for A Feast for the Eyes: Food as Fine Art www.mutualart.com (26 October 2011).

Macedonia, the traditional agricultural country of her birth, has strongly shaped her practice with its relationship with the natural environment (around 65 per cent of the land is covered in forest). Her remote mountainous home and her childhood spent exploring the countryside, or drawing and making and winning prizes for her sculptures, have all influenced her creative perspective. At eight she won her first sculpture prize and since then she has received many accolades. She has been resident in the United Kingdom since 1992, was showcased at the 51st International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia in the New Forest Pavilion with ArtSway and represented Macedonia at the 55th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia.

Hadzi-Vasileva journeys into new environments with relish – fresh challenges ignite her passions to respond to sites in unexpected ways, but always using materials that resonate with the locale. She elects to craft her installations meticulously and has little interest in materials of significant monetary worth, preferring to use the discarded to explore the concept of ‘value’. Her skill at manipulating pattern and texture are resolute, exquisitely illustrated in the work Reoccurring Undulation for Towner, the contemporary art museum in Eastbourne, UK. In Reoccurring Undulation Hadzi-Vasileva cleaned and preserved 960 salmon skins then mounted them on zinc plated tiles – the effect is a stunning undulating pattern in a subdued, natural palette.

The extraordinary tactility of her work was showcased wonderfully in The Wish of the Witness collection. Here the discarded animal carcasses and skins from Pied à Terre, the Michelinstarred restaurant, where Hadzi-Vasileva was the first artist-in-residence, were stripped and scoured, preserved and arranged. Reflecting the calibre of the host restaurant, she highlighted some of the animal parts in edible foil made from 23.5 carat transfer gold.

In Butterflies in the Stomach preserved caul fat was transformed into a maze of diaphanous drapery, the filigree echoing the history of lace in Valenciennes, where the gallery was located for her residency. 250m2 of pig’s stomach were suspended to form an ethereal labyrinth where visitors strolled among the meandering veils of organic waste bathed in the pungent odour. Hadzi-Vasileva elucidates on Butterflies in the Stomach:

The intricate and slow production methods of traditional lace-making resonate well within my work, where laborious and skilful work is required to make a piece of art. Here I brought together surprising cohabitants: lace and offal. Making a labyrinth out of caul fat that was just as intricate as lace-making.

For the Macedonian commission at the Public Room Promo Center, Skopje, Inherent Beauty, Hadzi-Vasileva sourced numerous pig stomach membranes to create a highly tactile tapestry. From afar the installation has a contemporary monotone design aesthetic, yet on closer inspection the caul fat reveals a sense of otherness that is unsettling: each square has its own unique visual poetry.

In 2013 she represented Macedonia at the 55th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, with the creation of a major installation Silentio Pathologia, reflecting on the unusual subject of migration of disease across Europe. In addition to current concerns she researched historical references of the legendary medieval plagues, to deliver an ambitious work juxtaposing rat skins, silkworm cocoons and woven silk against sheets of steel. Hadzi-Vasileva is at pains to highlight that in all her interventions the disembodied animals are all ethically sourced and are purposefully employed to have immediate impact, however distasteful. It is key for her that the commodification of animals is not a blinkered nor latent message but one that confronts. She has an innate skill at rendering such ‘unpalatable’ base material into exquisitely made and erudite sculptures and installations that are simply mesmerising.

Silentio Pathologia, 2013, Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva. Installation Macedonian Pavilion, Scuola dei Laneri, 55th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia. Steel, silkworm cocoons, silk, rat skins, live rats, bespoke cages, cotton and wire. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva)

Silentio Pathologia (detail), 2013, Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva. Installation Macedonian Pavilion, Scuola dei Laneri, 55th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia. Steel, silkworm cocoons, silk, rat skins, live rats, bespoke cages, cotton and wire. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Mark Segal)

Sculpture is poetry in three dimensions defined by the physicality of its mass, or lack thereof. The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

Michael Shaw is a British artist who specializes in creating curvilinear abstract sculptures that appear to dance in the clouds. His work often floats in space like a 3D mark drawn in the air. The singular forms nod to minimalist edicts, and Donald Judd’s influence is referenced, yet Shaw has harnessed an ethereal palette for many of his works to deliver sculptures with a unique signature. The simplicity of the forms disguises the complex design process that underpins his practice. His aesthetic language is articulated in the curve – he celebrates the innate appeal and geometry of the shape with dynamic versions of concentric, sinuous and curvaceous forms.

The dynamism of geometry is what, in my opinion, drives the language of sculpture. The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

There is a strong sensual quality to all his work, whether floating or wall-based, that demands to be caressed with a lightness of touch. His choice of a seductive palette embraces light and air as its main constituents – activating the void with delicacy and delight. Materials such as ripstop (parachute fabric), polyvinylchloride (pvc), acrylic, resin and nylon form the physical cradles, while he often uses stainless steel as the hidden armature. Harnessing the latest technologies, processes and materials to execute his works is a key element in his practice:

…the endless permutations of optical conundrum, as light both falls on, through, and is reflected by, tense curvatures of pressurized translucency.

Nigel Slight, Membranes and Edges exhibition catalogue essay, 2005.

Site-specificity added a liberating dynamic to Shaw’s practice with the design of inflatables meandering and twisting among architecture. INF 12 was commissioned by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London to encircle Bernini’s Neptune and Triton. Responding to the aquatic theme of the carvings, Shaw designed the inflatable to echo an undulating wave with its cycle of inflating and deflating motion. The elliptical form contorts to complement Neptune’s pose, while the sculpture’s gold lustre was inspired by the concept of a halo in celebration of the master sculptor, Bernini.

INF 13, 2010, Michael Shaw. Installation Schwartz Gallery, London. Ripstop parachute fabric, air, fan, digital timer. 1880 × 840 × 320cm. (Photo: Michael Shaw)

With INF 13 for the Schwartz Gallery in London, he created an eighteen-metre long sinuous sculpture that dominated the gallery space. Writhing and pulsating, dressed in a fluorescent pink casing, the form possessed an intestinal body laced with sexual innuendo. Responding to each site has led Shaw to emphasize and circumnavigate structural features, such as the cast iron pillars in the Schwartz Gallery. He finds the challenges stimulating and engineers the inflatables around the obstacles, such as stairways, mezzanines and doorways, so that there is a synthesis.

INF14 involved a curvilinear form winding its way around Gallery Oldham’s central lighting rig. Its orange counterpart descended like molten lava or an alien stalactite, only to be penetrated by the sinister flowering of the dark tendril. Whatever it was, it seemed on the brink of devouring the architectonic structure, like a giant intestinal parasite.

Michael Shaw, Chameleons and Shape Shifters II, exhibition catalogue, Gallery Oldham 2012.

Shaw is fascinated by the idea of the chameleon and investigating ways that he can bring this concept into his work through the manipulation of air, light, form and colour. His experiments have led to some intriguing interplay with surfaces and the viewer, and how the illusion is blurred towards reality. The inception of ‘breathing’ into his sculptures, as a notion towards living forms, has created a biomorphic resonance. The animation of timed inflation and deflation cycles enhances the readings towards more amoebic interpretation. Block colour, single textures and a limited use of materials underline his adoption of the minimalist doctrine, but Shaw then manipulates these with light to echo metamorphism.

INF 12, 2009, Michael Shaw. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Ripstop parachute fabric, air, fan, digital timer. 560 × 660 × 180cm. (Photo: Michael Shaw)

I am interested in the simultaneity of humour and distress, banality and the possibility of meaning.

Extract from artist’s statement, 2012.

Liliana Porter has an eye for capturing the humorous perspective of the human condition in her exquisite miniature installations. Born in Argentina and resident in the USA, Porter scours flea markets and antique shops across the Americas for finds that ignite her sense of drama to create poignant ‘theatrical vignettes’. She assembles her cast from inanimate objects, toys, ornaments and figurines, and orchestrates them to make commentary that charms and provokes the audience. Her sculptures often depict challenging scenarios that her miniature people are confronting with varying degrees of bravado or trepidation, reflecting the variance in man’s own character.

The Anarchist, 2012, Liliana Porter. Wall installation. Shelf with figurine and yarn. 142 × 110 × 26cm. (Photo: Liliana Porter)

The objects have a double existence. On the one hand they are mere appearance, insubstantial ornaments, but, at the same time, have a gaze that can be animated by the viewer, who, through it, can project the inclination to endow things with an interiority and identity.

Extract from artist’s statement, 2012.

Him (detail), 2012, Liliana Porter. Wall installation. 13 wooden blocks and acrylic on shelf. 14 × 109 × 26cm. (Photo: Liliana Porter)

Porter manipulates the spatial relationships between her subject and the void, believing the empty space to be almost a protagonist. By embracing the blank, abstracted space she intensifies the dialogue between the work and the viewer. She wants to transport the scene to a place without history or time to avoid the perceptual limits of a temporary context.

To Go Back (detail), 2011, Liliana Porter. Wall installation. Found porcelain pitcher, figurine, ink, and shelf. 18 × 61 × 15cm. (Photo: Liliana Porter)

Sculpture is formed by the many impulses of reality going though different prisms and filters, addressing our fears and affinities to reconstruct a certain time and space.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2012.

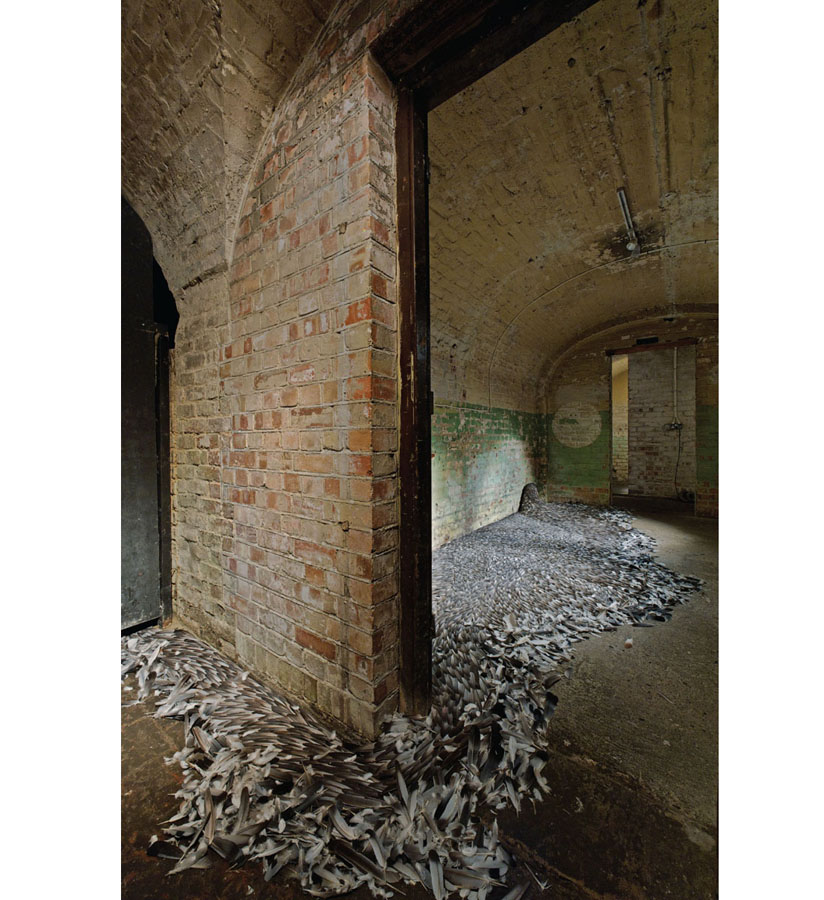

Nika Neelova creates dark, monumental sculptures that evoke a primal foreboding of the apocalypse. She is fascinated by the notion of the ruin and its narrative where time, place and our imposition of history entwine. Harnessing architectural structures and fragments, she references the embedded and physical residues of the objects to gain insight and proffer a genius loci. Her choice of a strong, muscular palette (judiciously limited to burnt, salvaged timbers, concrete, ash and graphite), further imbues the work with power and impact, underlining the prevailing lugubrious mood.

The work is addressing segments of existence that have or must collapse, referencing the disillusionement and the disintegration of utopias that ensues from their confrontation with reality. Often reminiscent of the past, the pieces are also presupposing a future in which this present shifts into a state of disrepair.

Extract from the artist’s statement, 2013.

Russian Neelova’s installations paradoxically possess a sense of otherness while abnegating human presence. The imprints of passing generations are subtle but revered, left to form the aftermath for future peoples to unravel. The paths she creates within the installations, where viewers can engage directly with the works, garner a rich tactility among the grave disquiet. The pervading atmosphere engenders a tension between repositories of memory against an erosion of place.

My work is often about introducing new narratives into recognizable situations and it is this ‘recognizability’ that instigates a more individual relationship with the viewers, activating their memories and personal associations. The collected and retrieved fragments, the history and origins of objects and materials give it an extra fourth dimension.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2012.

For Neelova the relationship to found building materials is profound. Addressing architectural fragments cements her ideas about memory and how a building can relate our experiences, however skewed from reality, in the reading of them. The lure of the study of the erosion of time, and how entropy and decay impact on function, remains her preoccupation. She aims to capture the moment before collapse and ruination – an ambitious challenge where the balance of fragility must be in tension against core strength. Towards this goal, Neelova manipulates the notion of ‘distance’ through the casting of objects to capture another state of existence - the original object becomes dysfunctional, while the cast object celebrates its own vulnerability. To underpin her conceptual message, Neelova pushes the materials to their limits casting them lightly and thinly so that they form cracks and become unstable.

In the sculpture Scaffolds Today, Monument Tomorrow, Neelova juxtaposes scorched reclaimed timbers against rope cast in paper. She comments,

The rope cast in paper becomes as hard as concrete, yet through this material transformation it also becomes incredibly fragile, as seen through the surface cracks and crumbling of the edges. Thereby the rope is distanced from its original form and deprived of all its original properties. Also, drawing references from the distant past, this piece focuses a lot more on the psychology of perception and embodiment.

Endless coils of cast rope are there to symbolize attachment and at the same time the complete failure and incapacity to get attached because of the natural fragility of its material. Cracks on the surface draw attention to the temporality of their representations. At the same time the hardness of the material, which is frozen in space, alludes to monumentality. The title draws references to its sense of loss and sense of belonging as well as the duality of interpretations.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

Fragments Shored Against the Ruins, 2013, Nika Neelova. Installation Vigo Gallery. Mixed media. 350 × 250 × 100cm. (Photo: courtesy of Vigo Gallery)

Burning meteors leave no dust, 2013, Nika Neelova. Installation Vigo Gallery. Cast concrete, aircraft cable. Dimensions variable: 210cm each piece. (Photo: courtesy Vigo Gallery)

In Burning Meteors Leave No Dust a collection of casts of propellers form sentinels of crumbling concrete. The casts were taken directly from antique aircraft propellers from the 1900s when Orville Wright defined his first successful airfoil as a twirling bird’s wing. The sensuous and curvaceous form transposes from its industrially manufactured resilience to a delicate piece of sculpture. Neelova manipulates the traditionally substantial and strong building material of concrete to appear fragile and unsafe – to engineer a conflict with the iconic propeller form. The dream of flight is shattered through the heavy anchoring to the ground.

Partings, 2012, Nika Neelova. Installation The Crisis Commission, Somerset House, London. Original Somerset House Georgian door cast in concrete, burnt timber, rope. 500 × 400 × 300 cm. (Photo: courtesy of Sam Mellish, David Roberts Collection)

The journey towards commemoration is investigated, played out and celebrated in Commemoration – a series of plaques cast from original coalhole covers. The path of commemoration has a lateral thread for Neelova, one that references the historical associations with religious altars, funerary monuments and memorials. She delivers a contemporary twist to the traditional practice by casting them from charcoal dust and graphite – both subject matter and classical artistic medium. Embedded in pavements and locked from inside the house, the covers hide a chute that directly leads to the cellars. Now, with the coalhole covers mainly redundant due the passing of the Clean Air Act, Neelova commemorates their history in this series.

Denied the possibility to serve their original purpose, they [the objects] become images of deprivation and interruption, reflecting of the past and present of existence in the time of ruination.

Extract from artist’s statement, 2013.

A commission for The Somerset House & Christie’s Crisis Commission consisted of eleven original Somerset House doors cast sparingly in concrete, then displaced in space. The work, aptly titled Partings, presents the doors without purpose, no longer a useful device for division and separation of environments. She ties the pieces in place with rope to dislodge any useful interpretation of them as openings or as their original role. The sculpture stands strong as testament to her artistic voice.

Commemorate sw19 series, 2013, Nika Neelova. Charcoal dust and graphite. 36cm diameter. (Photo: courtesy of Vigo Gallery)

Commemorate w8 series, 2013, Nika Neelova. Charcoal dust and graphite. 36cm diameter. (Photo: courtesy of Vigo Gallery)

Commemorate wc1 series, 2013, Nika Neelova. Charcoal dust and graphite. 36cm diameter. (Photo: courtesy of Vigo Gallery)

In sculpture I am celebrating the beauty of the overlooked natural object.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

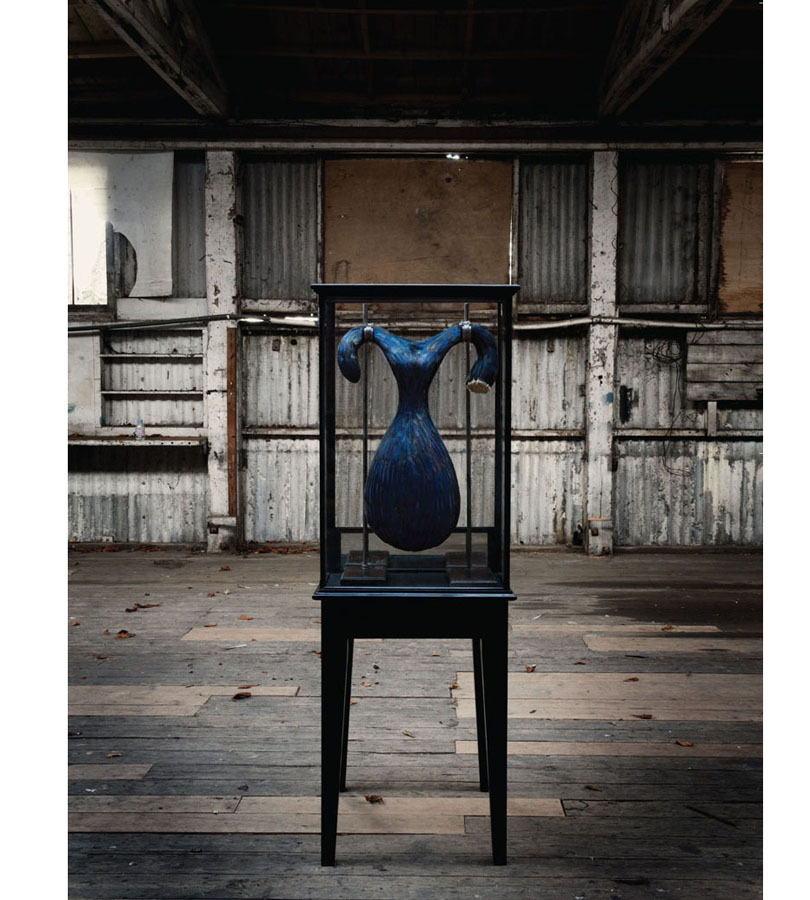

Kate MccGwire creates voluptuous sculptures that hypnotize and beguile with their sensual beauty and intriguing symbolism. The humble feather is transformed in MccGwire’s hands into ambiguous swirling forms imbued with references to the human body, water and animalia. These ethereal sculptures capture texture, pattern and colour to mesmerizing effect – it is difficult not to seduced by the curvaceous feathering with its lustre and iridescence.

Feathers became MccGwire’s muse some years ago, when moulting pigeons innocently shed feathers near her studio, striking a particular resonance with her as a progression from her work with another keratin source, human hair. The natural environment has played a key role in her life and the innate pull to the organic is manifest. She has always had a symbiotic relationship with rivers, growing up in Norfolk, England, with a boat-builder father and three siblings ready to mess about on the water. This continues today with her studio which is in a 150-year-old Dutch barge moored to an island on the River Thames.

Working on the river is amazing because you get this constant fantastic light. I’m totally aware of the seasons, nature and temperament of the river, and that really feeds into what I make. The island itself it also fascinating, as well as being a rustic idyll it is also a 1940s’ time capsule on a grand scale.

Extract from an interview for Coates and Scarry, 2012.

Gyre, 2012, Kate MccGwire. Crow feathers and mixed media. 415 × 770 × 275cm. (Photo: Tessa Angus, courtesy of All Visual Arts)

Sluice, 2009, Kate MccGwire. Installation The Space Between, The Crypt, St. Pancras Church, London. Pigeon feathers and mixed media. 450 × 250 × 500cm. (Photo: Francis Ware)

Coerce, 2012, Kate MccGwire. Mixed media, magpie feathers, antique cabinet. 175 × 61 × 61cm. (Photo: Tessa Angus, courtesy of All Visual Arts)

MccGwire elaborates on her passion for the natural environment:

The peculiarities of the everyday are inspiring to me; the contradictions, patterns and impossibilities of nature are a source of endless fascination. I’m constantly in awe of how the world works on both a micro and macro scale. From the precise engineering of a feather to the patterns of a murmuration of starlings, the world is a boundless muse.

Inter view between the artist and writer Matilda Lundberg, Odalisque magazine April 2013.

There is a commanding aura that pervades all the sculptures – a sinister echoing from another time and place. This otherworldliness embraces the dark side and embellishes the mysterious – both dimensions MccGwire takes pains to imbue in her exquisitely crafted pieces. These qualities have enamoured commissioners to let the artist’s vision expand into sitespecific installations. Evacuate is a major installation work that was originally designed for Tatton Park Biennial in Cheshire, where it stealthily funnelled out from the old blackened cast iron kitchen ovens and across the floor in search of an escape. MccGwire, inspired by the history of feasting on game at the mansion, collected locally sourced poultry and game feathers to make the pieces. In Sluice, for The Crypt, St Pancras, London, pigeon feathers appear to be shot from a hole. MccGwire comments on the installation:

Pigeon feathers spew, forced by some kind of subterranean pressure, from a hole in the floor, to create a swirling vortex of effluence, at once exquisite and disturbing. Extract from artist’s website, 2013.

MccGwire’s oeuvre reflects her influences from the Surrealist and Abjectionist movements and their preoccupation with dislocating beauty and horror to expound disjointed realities. She is absorbed in transposing the duality of the wonder and the darkness of nature in her work. Many of her sculptures writhe and contort, resemble fluid – paradoxically static in site, but virtually full of motion in the rhythmic undulations. These confusing illusions are extolled by the interplay of carved form and intricate manipulation of components. She explains in an interview for Coates and Scarry:

I’m constantly trying to create this fine line between attractive and vaguely disquieting, they are bodily, so we recognise creases and crevices yet also alien and strange. The work uses natural patterns to suggest familiarity and truth yet they are impossible creatures; it’s more like a suffocation or tightness, a manifestation of a feeling or an emotion as opposed to an actual thing. The intent is to produce something that can be read on many levels, both visceral and cerebral at the same time, a Möbius strip both in form and meaning.

The inclusion of obvious restraint, through employing antique vitrines and glass domes normally aligned with taxidermy, in which to squash and display her prey, further questions the association with the sciences and natural history – a collection of Victorian curiosities is evoked. Judith Collins in her essay for the Lure publication says, ‘The viewer approaches with a sense of anxiety, as though stepping too close will cause the apparently headless creature to rear up and break free of its bondage. Something ancient and extinct seems to have the power to come alive.’

MccGwire aims for abstraction – the viewer to ponder on the non-specificity and the possible symbolism of the entwined, embraced and the foil of entrapment.

My experience of beauty and ugliness is of two visceral emotions that intertwine rather than of two separate entities. It’s a relationship I see mirrored in the natural world where there’s both darkness and light – two halves of the same idea; you can’t have one without the other. Working on the river, as I do, means I get to see nature at its most raw – you literally watch as the ‘bucolic idyll’ unravels before your eyes. It’s a never-ending cycle of birth and death, of one animal preying on another, of harsh realities and unhappy endings with fluffy ducklings being snatched by other, carnivorous birds. It’s both beautiful and horrifying.

The artist in conversation with Maria McKenzie, Glass Magazine, March 2013.

Sculpture is about understanding the world through the manipulation of stuff.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2012.

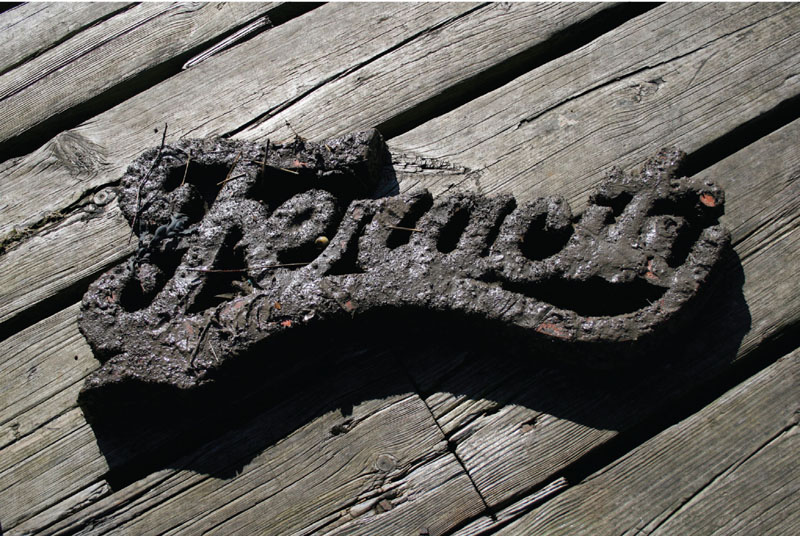

Cath Keay’s sculpture celebrates the notion of a continual coming into being by a metamorphic engagement with living organisms. By deliberately letting her control over the work go, she achieves a liberation that imbues the piece with renewed energy. The next stage is a second life for the sculpture, where nature interferes in the work. The paradoxical interconnectedness between construction, destruction and rejuvenation is a key element of Keay’s oeuvre.

Keay has two passions that guide her practice: one is for 1930s architecture, the other is for employing text in her sculptures. British-born Keay enjoys expanding her horizons and has a truly European practice – combining her love for words and architecture with a continental twist.

The 1930s are the decade furthest in the recall of most of our oldest relatives and acquaintances, a moment of utopian thought that subsequently hardened into dogma. I researched Italian Colonie and Case del Balilla from this era as vivid architectural forms expressing the recollections of some generations ago. They show a playful innocence in the shadow of impending war and upheaval, mirroring the Futurists’ transformation of engineering feats into aesthetic ends in themselves. Cath Keay, British School at Rome Fine Arts, 2008–9 (extract from the exhibition catalogue).

Tirrenia and Late in October, 2009, Cath Keay. Foundation beeswax, aluminum. Tirrenia 70 × 50 × 15cm. Late in October 180 × 12 × 12cm. (Photo: Cath Keay)

Beehive, 2002, Cath Keay. Working beehive inspired by artist’s grandmother, Isobel Gordon’s exam drawings for a department store in 1933. Cedar wood, aluminium and bees. 70 × 70 × 110cm. (Photo: Cath Keay)

Using the attributes of beeswax foundation sheet for her scale models of 1930s’ buildings, Keay shapes the pliable sheet into abstracted miniature avatars of modernist buildings. Her fascination for the iconic architecture directs in-depth research that underpins her sculptures. Each exquisite piece illustrates her expert making skills and sensibilities.

In Calambrone, the Colonia Principe di Piemonte takes the form of an aeroplane if viewed from above, as an architectural embodiment of the contemporaneous Futurist aeropittura. In Cattolica, dormitories suggest streamlined trains welcoming expatriate children. These optimistic holiday buildings appear free from the dictates associated with the modernism of the later Fascist era, yet commands written on the walls belie an insipient credo of regimentation.

Cath Keay, British School at Rome Fine Arts, 2008-09. (extract from the exhibition catalogue)

Celebrating text that possesses ambiguity or has the intrigue of a foreign tongue, and then allowing living organisms to transform it, invokes her interest in transient phenomena. She has a fondness for historical typewriter typeface for its utilitarian appearance – she has formed it in clay and wood and also picked it out with bullets dropped in honeycombs. Keay is also drawn to a flowing cursive script, often used in old advertisements. Ristorante was her first play with florid fonts, where a cardboard case in the shape of the word was filled with oats. The bird food soon attracted the pigeons and a performance element naturally developed. Its success led to the development of script cast in terracotta clay: Fecundity, Feracity and Uberty, were then placed in tanks of seawater and colonized by marine organisms.

Metaphoric comparisons between human and animal societies permeate much of my recent work. The resultant un-authored forms have in turn suggested further anti-formal methods with clay and wood veneers.

Extract from artist’s statement, 2013.

Keay was keen to expand her ideas to capture the notion of a utopian landscape, once dreamed by architects for nearby Middlesbrough, with a more interactive bias. She modelled landmark Brutalist and Modernist buildings in wood then made them into working beehives. These were placed around the city, in the care of local beekeepers, to draw attention to the value of bees to our society and the incredible design and building skills they possess. To maximise the message she engineered a webcam and designed a limited edition of ‘make-your-own-beehive’ packs.

The Middlesbrough landscape is punctuated by remnants of grand visions and laudable ambitions. This work will reassesses these structures; the perceived brutalism will be tempered by their change of scale and their re-colonisation by the natural world.

Industrious colonies of worker bees prompt endless metaphorical interpretations of our own society. However, it is the insects’ architectural abilities that particularly interest me: they follow strict building regulations including east-west alignments of new built comb, regular bee-space corridors ensure easy passage, and all constructions show an astonishing economy of material resources. The modularity of Modernist architecture has strong parallels in what is required for beehives, to enable empty units (called ‘supers’) to be added to accommodate a growing population.

Extract from artist’s statement for rednile projects, Gateshead 2013.

Feracity, 2010, Cath Keay. Sculpture after being submerged in sea for two years. Terracotta, silt and marine organisms. 90 × 40 × 12cm. (Photo: Cath Keay)

My vision of practice has expanded beyond the physical and I look more to an attitude of transformation as being ‘sculptural’ whether it be material, the journeying of ideas or even something as alchemical as the working of the self. For me it resides in an intensity of presence rather than materiality and whether one calls it ‘sculpture’, ‘art’ or something else entirely; is only of taxonomic interest.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

David Chalmers Alesworth’s world combines his love for his adopted country Pakistan with that for his English birthplace, and with his interest in how the historical imprint of Empire interfaces with the present. His world orchestrates art and horticulture in a unique mix that delivers profound works of art that cross both continents and time.

A sense of place has been fundamental to my understanding of the world, the landscape and the living elements in particular. Over the last decade as an artist and researcher I’ve become more involved in issues of identity and the post-colonial.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

Alesworth aims to ‘bridge my psycho-geographical readings of Lahore city with other cultural signifiers’ through the study of impacts from historical colonization of Asia. His fascination with anthropological entropies, and with the deliverance of taxonomies as a legacy from the imperialists, is mapped in his practice. However, his astute observance reveals an intelligent convergence of pathways of comprehension and an appreciation of the realities behind historical records. Alesworth’s art is one of contemplation rather than a robust polemic, articulated in often-frail materials that contain a sensuous, tactile and handmade impulse.

The culture of Pakistan, with a high cultural value assigned to the handcrafted, tribal textiles and hand-knotted carpets in particular, and Alesworth’s research into the post-colonial led him to Michel Foucault’s theory of heterotopia.

... perhaps the oldest example of these heterotopias that take the form of contradictory sites is the garden. We must not forget that in the Orient the garden, an astonishing creation that is now a thousand years old, had very deep and seemingly superimposed meanings. The traditional garden of the Persians was a sacred space that was supposed to bring together inside its rectangle four parts representing the four parts of the world, with a space still more sacred than the others that were like an umbilicus, the navel of the world at its centre (the basin and water fountain were there); and all the vegetation of the garden was supposed to come together in this space, in this sort of microcosm. As for carpets, they were originally reproductions of gardens (the garden is a rug onto which the whole world comes to enact its symbolic perfection, and the rug is a sort of garden that can move across space). The garden is the smallest parcel of the world and then it is the totality of the world. The garden has been a sort of happy, universalizing heterotopia since the beginnings of antiquity.

Extract from Michel Foucault, Des Éspace Autres, 1967.

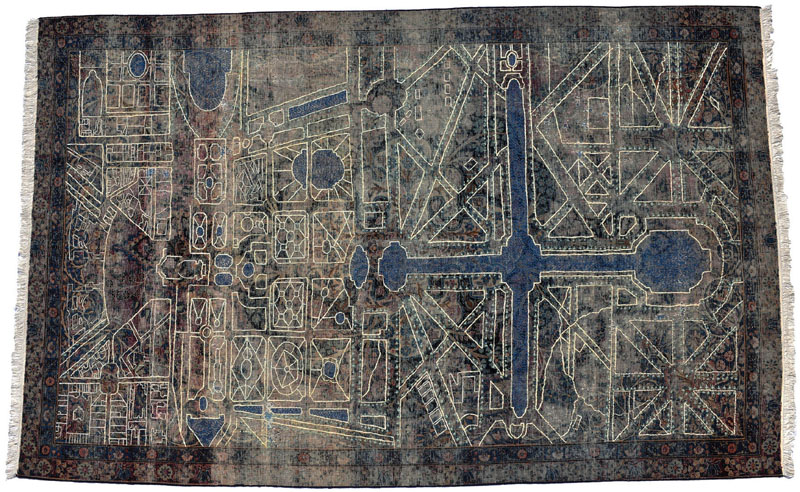

This has guided Alesworth’s concept of mapping his political commentary on worn carpet. The collection of carpets, that he calls his ‘textile interventions’, are embroidered with plans of the great gardens of Empire.

In Hyde Park, Kashan 1862, Alesworth has transposed a fragment of a historical Stanford map. The old plans reveal part of the original Crystal Palace for the second Great International Exhibition in Hyde Park in London. Through beautifully stitching into the respectfully restored seventy-five-year-old Kashan rug the details are newly etched and documented. The date is key as it returns the viewer to the time shortly after the annexation of the Punjab to the British Empire. This era is a landmark in British history as it references the time when the monarchy reigned over a quarter of the world’s population.

The intersection of pragmatic European garden history (with its references to monarchy, the Empire and its might), and the metaphorical depiction of the eastern paradisiacal garden speak of domination through power. The juxtaposition also brings into focus the artist’s [Alesworth] own position as an Englishman who has lived in Pakistan for more than two decades.

Hammad Nasir, Lines of Control, A Green Cardamom Project, British Council Galleries, London 2011.

In Garden Palimpsest, the Palace of Versailles estate in France, after Abbé Jean Delagrive’s plans in 1746, is demarcated with stitched wool into an antique Kerman carpet. Versailles was selected as it has a strong relationship to the history of Islamic gardens. The potency of line of the embellishment is a powerful over-writing of cultural texts, and adds a layer of meaning beyond its delicate intervention. It references the point in the famous estate’s history where Louis XIV spread his power across the world in conquering and colonizing nations. Poignantly, the Kerman threadbare carpet had lost its rich, vibrant tactility, where many feet have passed over its pile and dust had lodged in its weave, eroded its beauty. Alesworth restored the 150-year-old rug with help from a team of local studio assistants.

Hyde Park Kashan,1862, 2011, David Chalmers Alesworth. Antique hand-knotted Kashan carpet with dyedwool embroidery. 345 × 234cm. (Photo: David Chalmers Alesworth)

Garden Palimpsest, 2010, David Chalmers Alesworth. Antique hand-knotted Kerman carpet with dyed-wool embroidery. 319 × 198cm. (Photo: David Chalmers Alesworth)

Both Versailles and the Royal Hyde Park were conceived as spaces of privilege, apart from everyday life. The Persian concept of the walled garden was also a seven space apart, pairidaeza – ‘pairi’ meaning ‘around’ and ‘daeza’ meaning ‘wall’ and so ‘walled garden’. The English word paradise has its roots in the old Persian word pairadaeza.

In both works at the level of the carpets themselves and their overlaid designs water is a dominant theme, the subtle essence of water within surrounding desert of the charbaghs and the excess of water in the Serpentine and in Le Notre’s grand canal at Versailles. Today water is one of the critical environmental issues, particularly in the subcontinent.

‘The garden’ is every culture’s central metaphor for its relatedness to its ideal of ‘nature’. Though any ideation of ‘Nature’ as something apart from us is completely eroded – as is any simple idea of cultural purity.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

Both Garden Palimpsest and Hyde Park, Kashan 1862 offer us pragmatic narratives of landscape gardening from European history, and Alesworth’s use of metaphor entwines an anthropological matrix of power and domination. Through his time as a citizen of Pakistan, Alesworth has explored his adopted country through noting the visual codes, both explicit and implicit, and rendering them through artistic statements with a geographical footprint. The cross-fertilization of interests in art and horticulture has led to a unique political commentary using unexpected materials – these messages appear to be tempered by the patina (of their re-crafting and prior useage). His work is shown around the globe and ironically is well received by the very nations who form the work’s subject.

Sculpture relates to the real world, to inhabited space, to the constructed environs we inherit and inhabit.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

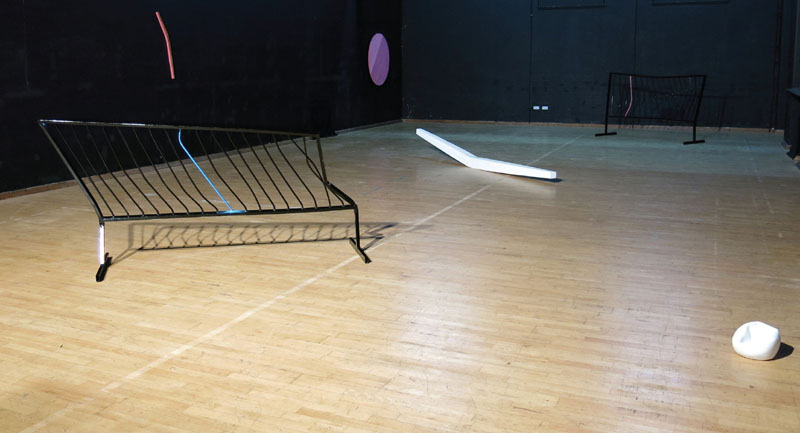

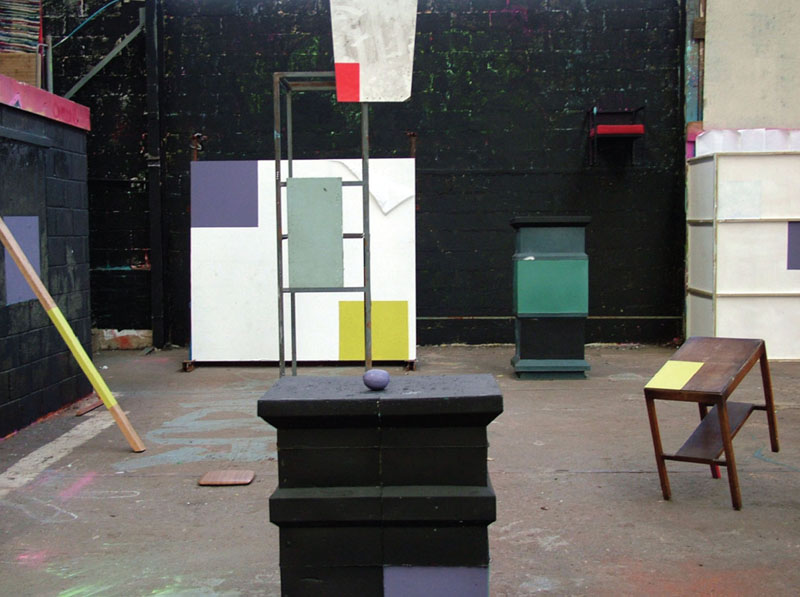

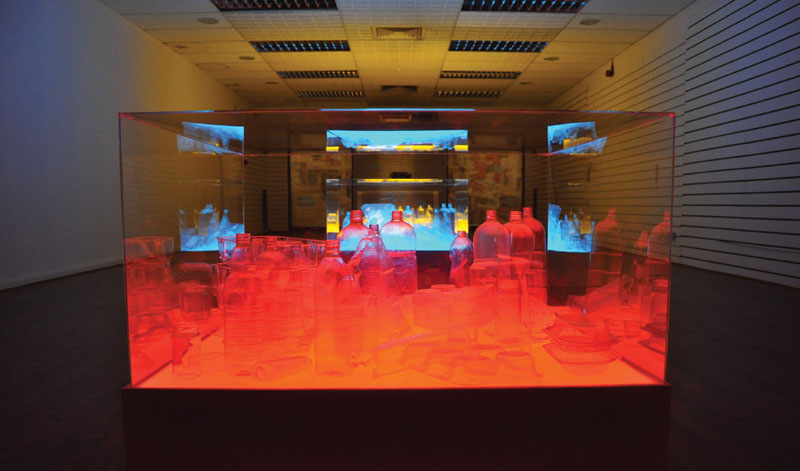

Mark Houghton works masterfully with the poetics of space and the juncture in tension between found objects placed in the context of his defined boundary. He is a visionary conductor, orchestrating objects so that they become redefined in his hands – delivering bold graphic statements from materials usually unseen and unvalued. Colour has a dynamic potency in his installations, married with form, texture and scale – the juxtaposition of the elements has a geometric harmony that resonates in its mathematical equation.

My search is for portent and potential narrative in the overlooked and seemingly insignificant aspects of the everyday. We are all surrounded by the evidence and detritus of almost 40,000 years of the activity of Homo faber (Man the Creator), and any landscape can essentially be read as an inescapable narrative of intervention. Therefore, I feel it important to celebrate and highlight the overlooked elements, the anti-monuments and non-events of that landscape, as I feel that these are equally relevant, when we are attempting to decipher a given landscape. Discarded items, the un-thoughtabout gaps between buildings, etc., these all have visual qualities that feed into, and inform our piecemeal absorption of our surroundings, that subsequently help us to order and decipher the complexity of the environments we inhabit.

Extract from artist’s statement, 2013.

Houghton’s material palette liberates and embraces the world of the found object. He does not belive in a hierarchy of materials and believes instead that ‘everything is up for grabs and reinterpretation’. The initial inspiration for his sculptures can appear quite inconsequential – chance finds in a junk shop, a line from a song or an unusual positioning of items in the street. Houghton works directly with the materials, believing that this embraces the spontaneity that is crucial to his approach. This has led him to specialize in creating site-specific works. He uses only objects he has found on site and then harnesses their power to make his visual statement. This selfimposed remit engenders a fascinating strangulation of both physical geography and psycho-geography and is one that Houghton relishes. In 2011, Occindental Collusions took form from materials found only on site in Carmathen, Wales – it reads with an interplay of rhythm and the exacting distance Houghton calculates between the placements, that imbue significance where before there was neglect. The neutral colour palette and sensitive lighting create synergy among the discordant artefacts, releasing an ambiance to the onlooker that reassures them it is safe to enter this new domain.

The unnerving experience of meeting Houghton’s work seems somehow closer to reading an instruction manual in a foreign language, but with lovely diagrams.

His practice is a prime example of that which confounds any attempt at a conscious, logical reading. It requires a lateral shift in thinking to be appreciated, which is often kick-started by a ‘key’ element in the work.

Chris Brown, March 2009.

Perfect Imperfection, 2013, Mark Houghton. Found and constructed objects. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Mark Houghton)

Occidental Collusions, 2011, Mark Houghton. Installation West Wales School of the Arts. Materials found on site and video. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Mark Houghton)

Memory of Lemon, 2010, Mark Houghton. Site specific response for the DIY Exhibition for Surface Arts, Exeter. Made from objects and materials found on site. Dimensions variable. (Photo: Mark Houghton)

Dresden is Yellow, Eternity is Pink is another site-specific work where Houghton limited his source materials to those found within a defined boundary of the site in Nottingham. The composition not only echoes his roots in painting, but resembles a 3D animated painting that you can enter and languish inside. The bathing of colour heightens the dynamics within the environment and showcases the sculptor’s innate sense of the value of juxtaposition.

Working Order, in London, adopts a similar approach but this time the execution has a softer appeal – drapes caress the floor, a chair and a pallet, the suspended spheres are balanced with the rigid wooden facets. The mood is gentle…soft, pink and inviting.

In Memory of Lemon, the site-specific installation created in 2010 for Surface Arts, Exeter, Houghton again gives colour the commanding role. Here the influence of Portuguese sculptor Pedro Cabrita Reis is felt – as a dominant artist in the minimalist genre who harnesses colour to exact poetic power, it is difficult not to see nuances of Reis’s style. However, Houghton’s interventions, with his highly individual and quirky selection of appropriated finds, have a very British signature on them.

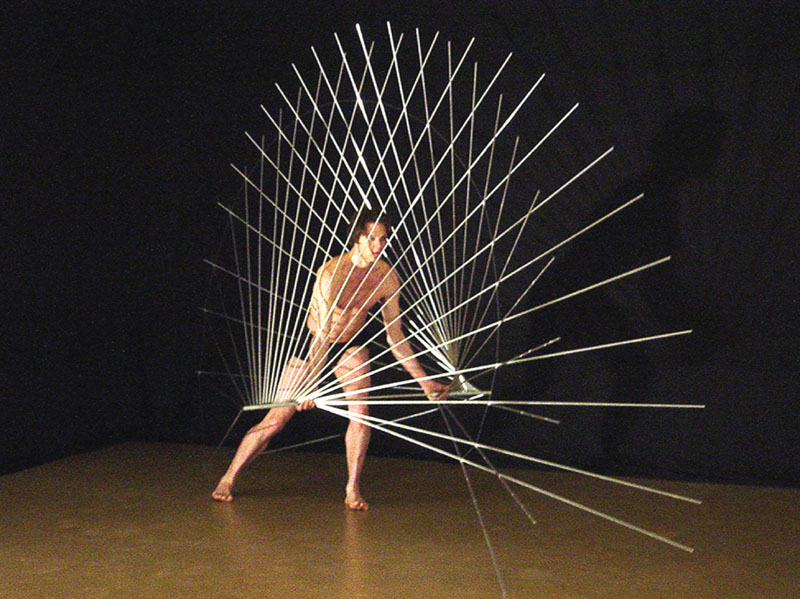

Making sculpture is the ultimate commitment to embodiment.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2012.

Marilène Oliver addresses both the physical and psychological relationship between the human body and the technological parallel worlds of the virtual. Through altering and reconfiguring the boundaries of our reality and our identity she transports us into a highly analysed and dissected universe. Her work embodies this relationship manifesting in a variety of guises but always with the human form at its core. Her conceptualizing of different ‘datascapes’, including Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Computerized Tomography (CT) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan data, provokes a new way of understanding the connective tissue of ontological entity being eternally entwined with technology.

The virtual world provides no place for the physical body. As the boundaries between our virtual and real lives increasingly blur, the absence of the physical in the virtual space is destined to provoke changes in the physical body and in our relationship to it in the real world. My work centres around this relationship, seeking to explore and create ways of intimately representing the physical/digital body.

Extract from the artist’s statement, 2013.

The initial inspiration for Oliver’s unusual work was the medical dissection and technological documenting of a convicted criminal, Joseph Paul Jernigan, after his execution. Medical scientists used a dataset of cryosections, CT scans and MRI scans to create a ‘Visible Human’ from voxel strata. Oliver elucidates:

To create the dataset, Jernigan’s corpse was frozen and sliced so finely that it disintegrated to mush, leaving only digital photographs and scans. The images of his body were uploaded onto the internet allowing him to be viewed at anytime and any place (but never all at once); he was under constant threat of being copied or translated. I downloaded images of his body and printed them onto sheets of acrylic and then ‘put him back together again’. In making I know you inside out, Jernigan was relocated in

time and space; returned from a digital to analogue state; no longer decentralized, fragmented and prone, but centred, whole and upright.

Extract from the artist’s statement, 2013.

Heart And Womb, 2007, Marilène Oliver. Inkjet, screenprints in optichromic and interference ink on polycarbonate. 160 × 100 × 60cm. (Photo: Todd-White Art)

Dugout, 2013, Marilène Oliver. Laser cut and charred MDF, ink and adhesive. 220 × 45 × 60cm. (Photo: Pascal Helleu)

Oliver’s preoccupation with how flesh can be transposed into digital information requires her to work closely with radiologists, scientists and technicians. As an artist, she primarily seeks metaphors and poetic readings from the data transcripts, not strict anatomical analysis. However, in approaching repair of the fragmented body, she reveals a deep understanding of the human form. Identifying ethical and philosophical questions has come in tandem with her conceptual research extending to investigating ‘transhumanism’ and the development in robotics. Austrian futurist Hans Moravec’s writings have acted as a springboard for Oliver’s ideas.

In his book Mind Children, Hans Moravec suggests that the way for humans to survive in a post-flesh, data-based era is for them to download their consciousness to the datascape, leaving the physical body behind. My work responds to this hypothesis by asking how the body could be refigured, translated and preserved so that it too can enter (and reflect) the datascape. Digital medical imaging fragments the body, genetics breaks it down into code, electronic communication reduces interaction to emails, text messages – digital media breaks the body down into bytes. As a sculptor I attempt to repair the fragmentation and dislocation of the body brought about by medical imaging and electronic communication by using the digitized and coded body as material for making sculptures. I seek to reclaim the body from the contemporary medical and digital gaze to poetically subvert it and offer future relics of our increasingly digitized selves. Extract from the artist’s statement, 2013.

In Dervishes, Oliver’s dual passions of sculpture and printmaking are conjoined in a major work that reflects the notion of the datascape body as a kind of atrophied avatar. The aura of ephemerality that surrounds the sculpture evokes transient beings – created through the employment of dye sublimation printed on panels of glass organza, strung in sequence to visually rebuild the bodies, on a clear nylon line.

The impact of Oliver’s journey across continents is profound, markedly informing and shaping her research and artworks. This international perspective creates a global commentary on her universally important subject matter and its context. Oliver was born British but she has lived for significant periods in Brazil and Angola. She reveals, ‘Each place has influenced my work both in the way it has made me reassess the importance/role of the digitized body and also the materials and processes I choose.’ She found Rio de Janeiro liberated her practice, compared to the confines of London, and enabled her to express herself freely through carnival materials which were so readily available.

I came to Rio thinking I should surrender to fantasy and performance and allow it to help find innovative ways of materializing the DICOM database (which for me continues to be Melanix. I needed to readdress the balance of embodied (handmade, labour intensive, bodily learnt processes) and disembodied activity (working on the computer, exporting directly to machine) in my practice. My work should be fuelled by ‘Virtual Leakage’ and I need to allow objects to present themselves from ‘a back and forth exchange in which ideas migrate by osmosis’ (between the real and the virtual).

The artist in conversation with the author, 2012.

The sculpture Orixa embodies the Melanix dataset through an Afro-Brazilian portal of the Candomblé dance ritual. Layers of foam rubber are embellished with seed beads, horizontally stacked, arched and split open to receive a spirit. In contrast, Split Petcetrix is made using similar materials, but with vertical layering. Both sculptures possess a duality: rich and vibrant tactility that entreats, followed by a gentle rebuff when the subject matter is exposed.

In Dreamcatcher, Oliver extended the dataset to capture an exhausted carnival queen laid prone, created from layers of clear acrylic sheet. The fantastical narrative hides the digital intervention where the outline of Melanix scans had been converted to pixelated paths for laser cutting. She explains, ‘Dreamcatcher is a sculpture made up of close to 300 dreamcatchers. Each one is made using the profile of a scan from the Melanix dataset so that when they are installed they form a levitating figure, which floats above a cloud-like mass of feathers.’

This piece was later incorporated into a performance work, The Body in Question(s), curated and choreographed by Isabelle Van Grimde at the University of Quebec in Montreal, 2012. It is not surprising that Oliver includes collaborations with choreographers, as the main focus in her oeuvre is that of corporeal dialogue.

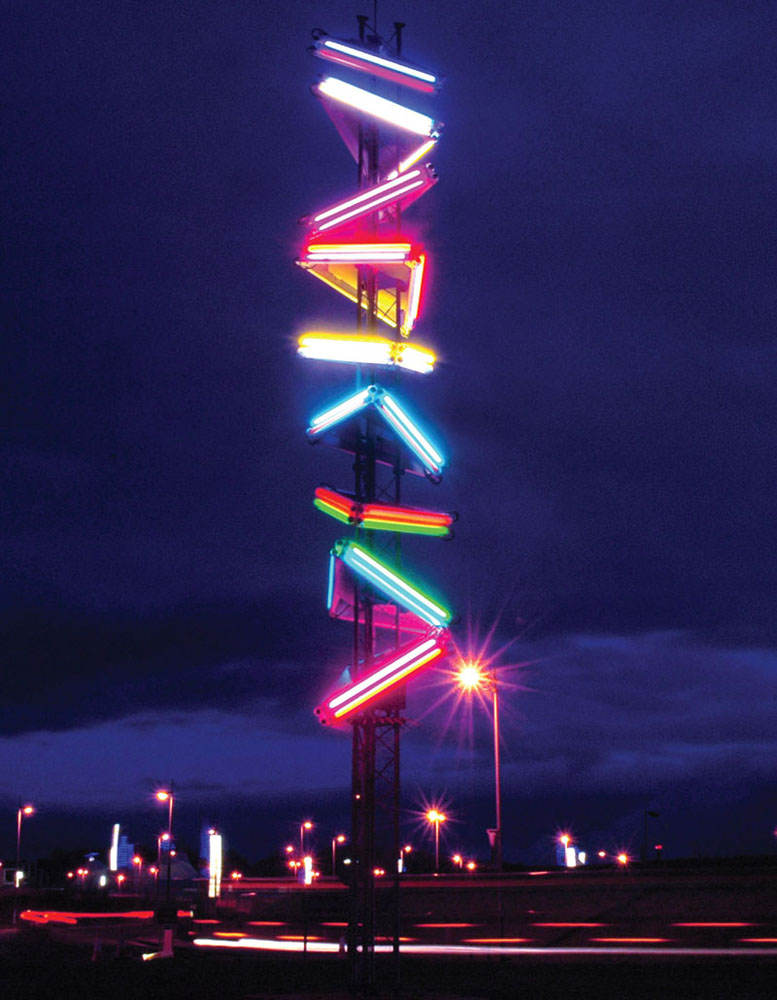

I see sculpture as a process of looking for poetic solutions that bring colour and life into the built environment.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

Peter Freeman is a master at creating spectacular interactive light sculptures that radiate joy and exuberance. His works expand the language of sculpture through paradoxically holding a powerful visual presence that has no tangible corporeality. The works appear always in transformation mode through the creation of an invisible force field that enables the public to interact directly and thereby possess a degree of control to animate the sculptures.

I’m interested in exploring qualities of light and space, using electric light and digital technologies to create luminous forms that have a positive ambience in their locations. Sometimes they are independent objects with luminous surfaces that radiate into the surrounding space. Others are light installations that integrate into the architectural envelope and transform existing structures. They often include interactive technologies to allow them to respond to the presence of people and the environment. I like to think this encourages a positive relationship between object and audience and makes the sculpture reflexive in its location.

Extract from artist’s statement, 2012.

Redruth, Green, Blue, 2011, Peter Freeman. Installation Redruth, UK. Textile banner and DMX programmed LEDs. Collaboration with artist Tony Minion and Redruth School. Dimensions 5 × 6m. (Photo: Peter Freeman)

Twist ‘n’ Tilt, 2004, Peter Freeman. Wakefield, UK. 12000 × 120 × 120cm. Painted steel tower with animated multi-coloured fluorescent tubes. (Photo: Peter Freeman)

British-born Freeman harnesses the role of light in our urban environs by creating art in the public realm. He uses light as his muse to create a dialogue between the passer-by and an environment, or to punctuate a building. His father’s profession in the ministry inspired his work Luminous Motion – a commission for Winchester Cathedral. He comments, ‘My first memories of artificial light come from my family’s annual outings to see the Blackpool illuminations and the multitude of candles in my Dad’s church. This dual influence of the frivolous and the holy in the language of light continues to be a source of inspiration for my sculptures.’ For Luminous Motion he focused on the city’s position at the axis of religious and political pathways to deliver a thought-provoking columnar work made from mirrored polished steel pierced by 500 fibreoptic lights. The lights responded to mobile text messages contributed from passers-by, changing the formation of words and colours. The discourse created a tension in the context of the cathedral grounds and animated the environment for a younger audience. This adoption of society’s passion for techno-culture to transform public spaces is a preoccupation for Freeman.

The sculpture developed out of thinking about physical and spiritual pathways. I was impressed with the idea of Winchester as a city situated at the convergence of pathways, and how this gave rise to the city’s historical importance as a spiritual and political centre with its fantastic gothic cathedral. One of the inspirations for Luminous Motion is the medieval Christian idea of an Axis Mundi. This is the pivot at the centre of the universe, around which all creation rotates. It is also a symbolic silver thread that allows spiritual communication between heaven, earth and underworld.

For this project the emphasis is on modern routes, both real and virtual. I wanted to use contemporary light and new control technology to explore ideas of pathways and communication networks in the modern city through the language of light.

Extract from artist’s statement, 2003.

In 2007 Freeman was commissioned to create a dazzling punctuation with light for the former telephone exchange building in Penzance. The clients wanted to signify the building’s metamorphosis into an art gallery. Freeman, a resident in West Cornwall, took his inspiration from the peninsula’s embracing sea and sky, creating soft waves in diffused blues and greens. Lightwave, a fifty-five-metre glass facade pulsated with electric undulations ignited by the triggering of motion sensors as people walked by. The local weather also contributed to the background colour through a sensor sensitive to atmospheric conditions.

Light remains invisible until it is transformed by the eye and brain into a visual experience. In this subjective process the world we see is like a reflection of our own imagination. The advent of electric light gives us the possibility of totally new luminous forms.

Mostly electric light is used in banal repressive ways for work and commerce, but I’m interested in the liberating ‘wow’ factor of light and try to make light sculptures that playfully explore the symbolic nature of light to entertain and give form to a contemporary moment.

Extract from artist’s statement, 2012.

Redruth Green Blue expanded Freeman’s oeuvre in 2011 through a collaboration with textile artist Tony Minion and Redruth School Year ten pupils. Together they researched the industrial heritage of the town and then transfigured that onto a digitally printed building canvas, enhanced by lightemitting diodes of RGB quality. The giant banner showcases key architectural details selected by the team from a compilation of photographs taken by the students. It is illuminated by a strip of LEDs at the base of the installation that are programmed to change colour and evoke different moods.

I work closely with clients, local people, architects, manufacturers and urban planners. It’s a creative transaction between artist, audience and location, and the sculptural process becomes orientated to a synthesis, transferring what is exciting and valued in the surrounding culture into three dimensions.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

Immersed in an endless, dark sea of thick, black pitch that presses against one’s chest with such a force that it penetrates through to the soul, adrift, we stumble upon unsettlingly familiar forms lying lifeless on the sea floor. Sculpture is what one is left with, once these encountered forms are wiped clean of the dark pitch that engulfed their whole being, and their revealing, true nature is presented in front of us.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

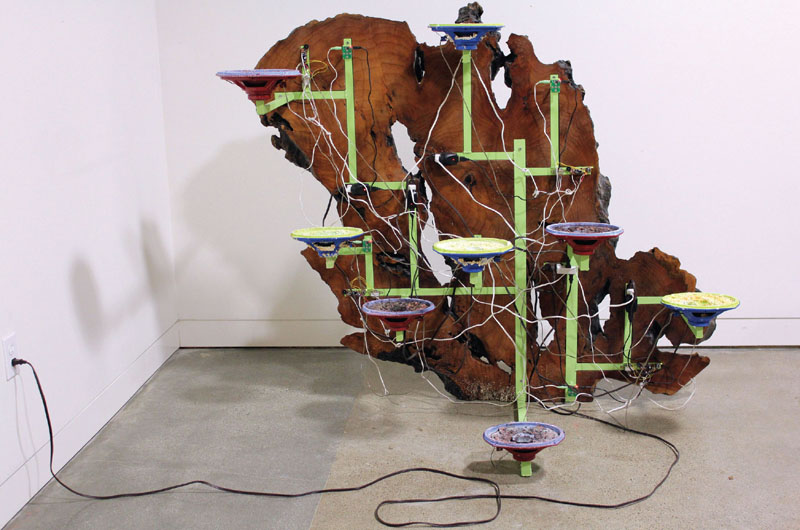

Stelios Manganis is a dark storyteller who harnesses humour, laced with solemnity and subversion, to relay tales of emotional toil through his mechanical sculptures. His unsettling and provocative narrative questions the tension humans create between themselves and the machines they build. He investigates, through his own fixation, how the reading of this relationship illustrates our fundamental understanding of our own emotions. Through dismantling and rebuilding he creates surreal metamorphosed machines that intrigue with sinister intent.

I consider myself an explorer, an investigator of the mechanical genome. I am in the pursuit of a common genetic code – one shared by both the machine and us humans. This is a type of research much closer to pseudoscience, if you wish, so perhaps I am more of a mechanical alchemist and a raconteur than an artist. Yet the work must be able to maintain equipoise between wittiness, irony and one’s real intent through the work’s subversive nature. People might find it hard to grasp the seriousness behind my works at first glance. They may leave the viewer uncertain as to its very nature – is it comedy or tragedy? I would like to think that the messages in these works are thought provoking and emotionally unsettling.

The artist in conversation with the author, 2013.

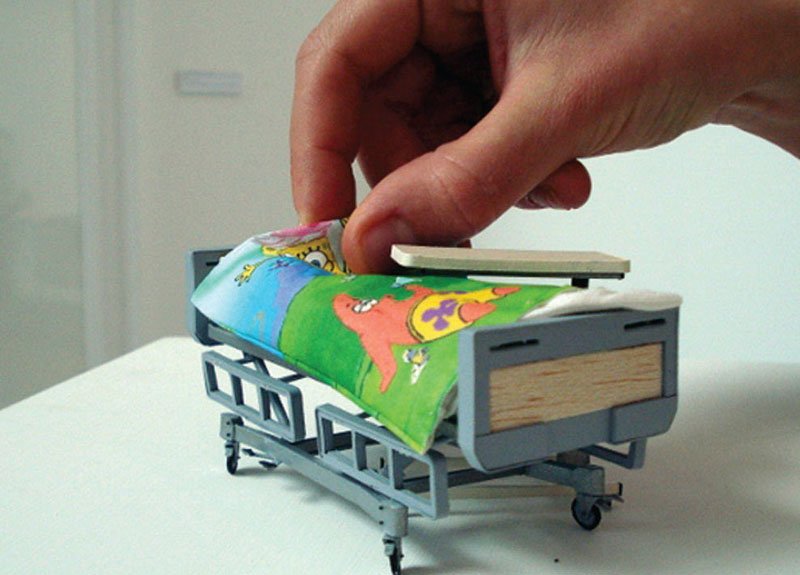

Manganis’ fascination with machines is endogenous, going beyond the initial wonder at the mechanics, to the realms of profound introspection. He aims to provide insight into the mind/body/machine continuum by constructing seemingly functional, hybrid machine sculptures that are only completed through human encounter. He elucidates: